Chapter 4

Marketing

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define marketing and explain its role in supply chain management.

- Describe how market segmentation impacts supply chain design.

- Describe the tools of customer relationship management (CRM).

- Explain the voice of the customer (VOC) and quality function deployment (QFD).

- Explain channels of distribution and their role in supply chain management.

- Explain the impact of e-commerce on channels of distribution and the supply chain.

![]() Chapter Outline

Chapter Outline

- What Is Marketing?

The Marketing Function

Evolution of Marketing

Impact on the Organization

Impact on the Supply Chain

- Customer-Driven Supply Chains

Who is the Customer?

Types of Customer Relationships

Managing Customers Using CRM

- Delivering Value to Customers

Voice of the Customer (VOC)

What is Customer Service?

Impact on the Supply Chain

Measuring Customer Service

Global Customer Service Issues

- Channels of Distribution

What are Channels of Distribution?

Designing a Distribution Channel

Distribution Versus Logistics Channel

The Impact of E-Commerce

- Chapter Highlights

- Key Terms

- Discussion Questions

- Case Study: Gizmo

Even before you enter an Abercrombie & Fitch store you can smell the characteristic woodsy aroma that is associated with the brand. A combination of citrus, fir-tree resin, and Brazilian rosewood extract, “Fierce” creates a sense of excitement and pleasure. Since its roll-out in stores across the country a few years ago, Abercrombie's cologne, which also pervades sidewalks outside the clothier's stores, has become an integral part of the shopping experience. A part of the ambience, the scent is designed to enhance the feel of being at the store, create brand association, and ultimately promote sales. Popular demand compelled the company to produce the trademark scent in bottle form. The brand association with the trademark scent has since become so strong that some customers even complain when store-bought T-shirts lose the smell after multiple washes.

Welcome to the new age of marketing—a form of sensory branding known as “ambient scenting” or “scent marketing.” Scenting the entire building is the latest ambition for building brand association and promoting sales. No longer confined to lingerie and candy stores, ambient scenting is custom designed to create brand association and a particular outcome. For example, Westin Hotel & Resorts disperses white tea, to provide the “zen-retreat” experience. The Mandarin Oriental in Miami sprays “meeting scent” in conference rooms in an effort to enhance “productivity.” Omni Hotels uses the scent of sugar cookies in its coffee shops.

Scent branding is becoming just as prevalent in retail, as researchers believe that ambient scenting allows consumers to make a deeper brand connection. Just recently Samsung had a scent designed for its stores with the intention to create an association between the brand and concepts of innovation and excellence. The creators even claim that customers—under the subtle influence—spend an average of 20% to 30% more time mingling among the electronics.

This new approach to reach customers has also created a new supply chain. A growing industry of companies worldwide specializing in ambient scent-marketing and dispersion technology has emerged. These enterprises typically pair with fragrance companies to design customized fragrances for businesses. There is also scenting equipment and technology for dispersion that must be designed, as well as equipment maintenance that can vary depending upon the size of the space to be scented. There are distributors, dealers, and agents that are added to the network.

As marketing develops novel alternatives to reach customers, improve brand recognition and enhance sales, supporting supply chains evolve. Marketing drives the development of the supply chain to meet what the customer wants.

Adapted from: “Etc. Branding.” Bloomberg Businessweek, June 21, 2010.

WHAT IS MARKETING?

THE MARKETING FUNCTION

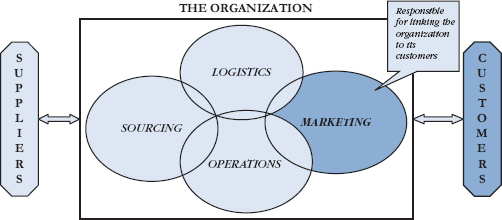

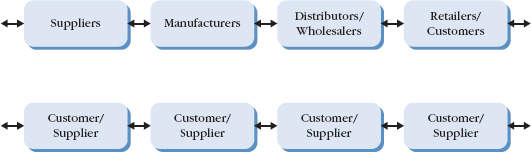

Marketing is the function responsible for linking the organization to its customers and is concerned with the “downstream” part of the supply chain. This is highlighted in Figure 4.1. The task for marketing is to identify what customers need and want, create demand for a company's current and new products, and continue to identify market opportunities. Marketing plays a critical role as providing value to customers drives all actions of the organization and the supply chain.

For an organization and its supply chain to be competitive, they must be better than competitors at meeting customer needs. Marketing is the function responsible for identifying what these needs are, determining how to create value for customers, and building strong customer relationships.

Marketing is a far more complex function than may appear, as customers are driven by much more than their basic needs for products and services. The key is to understand and develop the combination of products and services that precisely meet the expectations for a particular set of customers. For example, if most customers of athletic shoes only care for three different color choices, offering the product in five colors makes little sense. There would be little benefit and the supply chain implications—extra sourcing, manufacturing, distribution, and inventory—would be significant. It is critical to understand exactly what satisfies customers and to precisely match product and service offerings to their psychological needs or conscious preferences.

FIGURE 4.1 The marketing function.

Marketing is further complicated by the fact that there is no single market for any given product or service. All markets can be broken down into multiple segments, each of which has somewhat different requirements. A critical challenge is to distinguish markets—called market segmentation—in a meaningful and effective way. At one end of the spectrum is mass marketing, which refers to treating the entire market as a homogenous group and offering the same marketing mix to all customers. Mass marketing reduces costs through economies of scale but may miss large segments of the market with an offering that is too general. Segments that are too broad (e.g., all women in the world over the age of 30) do not permit the company to target a narrow enough group. On the other hand, segments that are too narrow (e.g., high school students who work part-time in Lima, Ohio) may not be cost-effective. Target marketing recognizes the diversity of customers and does not try to please all of them with the same product offering. The challenge for marketing is to identify the most effective market segments and their needs. As we will see shortly, this must also take into account the supply chain requirements needed to service each segment.

EVOLUTION OF MARKETING

The function of marketing has changed and evolved over time corresponding to changes in the general business environment. Three major perspectives dominated marketing over its history—the production concept, the selling concept, and the marketing concept, as shown in Figure 4.2. This most recent perspective also ushered in an era that focused on creating relationships with customers, called relational marketing, which is different from merely focusing on making individual sales transactions. We now look at this in more detail.

Gap Inc.

Consider that Gap Inc., one of the largest specialty retailers, owns three popular brands: Banana Republic, Gap, and Old Navy. Although all three carry fashion apparel, their target markets are very different. Old Navy carries “great fashion at great prices” and is focused on offering a low price point for a target market that includes families and children. Gap offers a classic style at a slightly higher price point targeting college age students. Finally, Banana Republic focuses on offering “accessible luxury,” has the highest prices point, and targets fashion-conscious individuals.

The three different brands have three different supply chains to support the different target markets. Old Navy has the lowest price point and primarily sources from China, which is driven by a focus on cost. Gap sources from South America with slightly higher quality goods but also higher prices. Finally, Banana Republic primarily sources from Europe. It offers highest quality fashion of the three brands, but at a higher price. The three different supply chains are specifically geared to support each target market. This strategy also gives Gap Inc. supply chain flexibility. When there are problems with any one supply chain the company can easily switch to one of the other chains to support its brands.

FIGURE 4.2 The evolution of marketing.

The early part of the 20th century witnessed large unfulfilled demand for products that met basic needs and gave rise to the production concept in marketing. At that time virtually anything that could be produced was easily sold and the primary challenge was to sell products at a price that exceeded the cost of production. Firms focused on products that could be made most efficiently as offering low-cost products in the marketplace automatically created demand.

The 1930s, however, witnessed greater market competition and ushered an era that now focused on selling. Mass production had become commonplace, competition had increased, and there was less unfulfilled demand. Unlike the time of the production concept, where mere product availability created demand, this new era required marketing to persuade customers to buy their products through tools such as advertising and personal selling. Marketing was a function that was performed after the product was developed and produced. The sales concept paid little attention to what the customer actually needed and the goal was to simply beat competitors at the sale. As a result, marketing often involved hard selling, something that is still associated with marketing.

The l970s witnessed a proliferation of product variety and greater selectiveness on the part of customers. Hard selling no longer could be relied upon to generate sales. Customers now had increased discretionary income and would buy only those products that precisely met their needs. In addition, in an increasingly global environment, their needs began changing rapidly and were not immediately obvious. The marketing concept developed in response, focusing on identifying what customers want and how to keep customers satisfied. Companies changed their focus to identify customer needs before developing the product and aligning all functions of the company to meet those needs.

The marketing perspectives prior to the l970s were part of an era termed “transactional marketing,” which focused on obtaining successful exchanges, or transactions, with customers. Companies focused on maximizing short-term transactions with their customers, as opposed to building long-term relationships. The focus was primarily on selling existing products and using promotional techniques to maximize sales, rather than developing insights into the future needs of customers. Then in the l970s firms moved from a “selling” orientation to a “marketing” orientation. Here marketing research techniques are used to understand customer psychology and then to make decisions that satisfy customers better than the competition.

The growth of supply chain management created a shift in philosophy regarding the nature of marketing strategy, termed “relational marketing.” Relational marketing focused on developing long-term relationships with key supply chain participants—customers and suppliers. The emphasis is to understand their long-term preferences, provide them with high customer service, and therefore engender loyalty. Relational marketing is based on the understanding that it is more cost-effective to retain current customers than to work to attract new ones.

The focus on customers has further been magnified with the turn of the century. Today's business environment is characterized by an empowered customer that is the driving force of the supply chain. The single greatest factor that contributed to this shift was the Internet, a technological development that armed consumers with a wealth of information and provided them with bargaining power unseen before. Consumers today have the ability to gain information on the latest product choices, product characteristics, costs and consumer reviews, and perform global searches of companies and industries. This has enabled them to become knowledgeable buyers who can realistically demand choices in products and services. Trying to accommodate this new breed of customers has resulted in a major shift in business philosophy and has changed virtually every aspect of supply chain management.

IMPACT ON THE ORGANIZATION

The knowledge and information that marketing provides has critical importance for the entire organization as it is used to guide the actions of all other functions within the firm. We can see this from the PepsiCo example, in the Supply Chain Leader's Box, where the entire organization is changing to accommodate new customer preferences. For marketing to be successful it must be supported by the entire organization and the products customers want must be made available.

As we have seen, it is common for marketing research techniques to determine that consumers desire a new type of product. Marketing then needs to work with operations to ensure production of the product with the exact characteristics needed; sourcing needs to ensure that supplies are available in a timely and cost-effective manner; logistics needs to ensure deliveries of exactly what is needed throughout the supply chain; also, finance needs to be involved in securing appropriate funding. All this coordination needs to happen simultaneously, while marketing is promoting and advertising the new product.

SUPPLY CHAIN LEADER'S BOX—ACCOMMODATING CHANGING CUSTOMER PREFERENCES

In February 2007, when Derek Yach, a former executive director of the World Health Organization and an expert on nutrition, took a new job with PepsiCo, his mother worried. “You are aware they sell soda and chips, and these things cause you to get unhealthy and fat?” she asked him. Yach's former colleagues in public health had similar concerns. However, Yach said he knew what Pepsi made, but he wanted to help guide the snack food multinational toward a more healthy product menu.

The company that made its reputation on junk food is changing its direction, under the leadership of Chief Executive Nooyi who took over in 2006. Nooyi says she has no choice but to move toward healthier fare, as consumers become more health conscious. For over a decade, consumers have gradually defected from the carbonated soft drinks that once comprised 90% of Pepsi's beverage business. Many have switched to bottled water and other healthier beverages. In addition, criticism grew steadily over Pepsi's largest business, Frito Lay snacks, which are laden with oil and salt. In response to changing consumer demands the company has decided to emphasize research to create truly healthy fare.

“Society, people, and lifestyles have changed,” Nooyi says. “The R&D needs for this new world are also different.” As a result, she has increased the R&D budget 38% over three years with the goal of expanding healthy products to $30 billion in sales, twice the company's overall historical average. To do this, Pepsi has hired a dozen physicians and PhDs, many of whom built their reputations at the Mayo Clinic, WHO, and like-minded institutions. Some researched diabetes and heart disease, the sort of ailments that can result in part from eating too much of what Pepsi sells. The goal is to create healthy options while making the bad stuff less bad.

The researchers hunt for healthier ingredients that can go into multiple products. Last year, technological improvements to an all-natural zero-calorie sweetener derived from a plant called “stevia” allowed Pepsi to devise several new fast-growing brands. This included healthier beverages such as Pomegranate Blueberry, Pineapple Mango, and Trop50, a variation on its Tropicana orange juice.

The question remains as to whether Pepsi's new strategy will prove profitable. What can be said with certainty is that consumer preferences have changed and Pepsi is working hard to respond to them.

Adapted from: “Pepsi Brings in the Health Police.” Bloomberg Businessweek, January 12, 2010.

Notice that marketing brings the voice, the mind, and the heart of the customer into the decision making process of the company. Collectively the organization then translates customer desires into viable and profitable products. None of this organizational functioning could take place without marketing to drive it.

IMPACT ON THE SUPPLY CHAIN

Just as marketing drives the decisions of the organization to produce and deliver exactly what customers want, it also drives supply chain decisions. Marketing decisions generally fall into four distinct categories known as the marketing mix or the 4Ps. These decisions are: product, price, place (distribution), and promotion. Although they are the domain of marketing, these decisions directly involve supply chain management.

Product involves decisions that encompass the bundle of product characteristics that satisfy customer needs. They relate to brand name and functionality. They also address decisions of quality and packaging, which are directly supported by supplier standards and logistics packaging decisions. Price refers to the pricing strategy developed for the product. This includes volume and sales prices, seasonal pricing, as well as price flexibility. Although the domain of marketing, pricing strategies and price flexibility are directly tied to supply chain costs. Place deals with having the product where it is needed and when it is needed. These decisions include selection of distribution channel and market coverage. They also include traditional logistics, sourcing, and operations decisions such as inventory management, order processing, transportation, and reverse logistics. Finally, promotion deals with advertising and sales techniques to increase product visibility and desirability. Decisions involve promotional strategies and advertising, sales promotions, and public relations.

In the past companies primarily focused on meeting the demands of the average customer. These companies basically supplied products to customers without trying to determine or satisfy the unique needs of each individual customer. Today, consumers are knowledgeable; they demand what they want at the highest quality, low price, delivered at record speed. Also, today's customers expect a world-class organization to provide high levels of customer service. To compete in this new economy companies are putting forth a great deal of effort and money to precisely understand their customers, to provide unprecedented levels of customer service, and to provide one-on-one customization. This has resulted in large changes in SCM of companies and the relationships between supply chain members who aim to deliver what consumers want. We now look at key issues in designing customer-driven supply chains.

CUSTOMER-DRIVEN SUPPLY CHAINS

WHO IS THE CUSTOMER?

Today's economy is characterized by a shift in power from companies to customers, where the customers are the dominant force. Customers now expect to receive the products they want, when they want them at a low price. As a result, companies are focused on capturing the individual customer, which requires a shift in focus from merely supplying goods and services to customers to actually capturing loyalty. The competition for customers has resulted in a proliferation of product choices and alternatives, which has had huge supply chain implications.

The focus on the customer has required supply chain companies to work together in order to provide customers with more value than competing supply chains. As a result companies are making large changes in their organizational structure and their supply chain relationships.

A company's supply chain contributes to its success because it provides more value to the customer than a competing supply chain. This may mean that it provides superior delivery and greater product availability. In order for supply chains to meet customer demands, they need to know exactly who the customer is. This also requires an understanding of the term “customer.” Most people assume that the term refers to the final customer or consumer. However, supply chain management as a concept requires a careful understanding of the term “customer.”

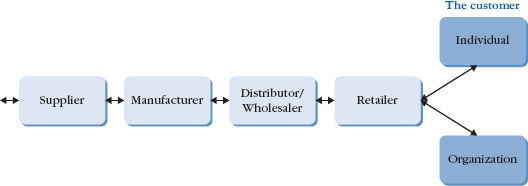

The “customer” can have many different meanings. Typically there are two types of end users. The first is the end consumer, which could be an individual or a household that purchases products and services to satisfy personal needs. The second type of customer is an organizational end user. In this second case, purchases are made by an organization or institution in order for employees to perform their jobs in the organization. A SCM perspective requires that all firms in the supply chain focus on meeting the needs and requirements of customers, whether they are individual consumers or organizational end users. This is shown in Figure 4.3.

From a SCM perspective, a customer is at any delivery location, not necessarily the last location in the supply chain. This includes a range of possible locations from consumers' homes, to retail and wholesale businesses, to the receiving docks of manufacturing plants and distribution centers. Often the customer is a different organization or individual than the one who is taking ownership of the product or service being delivered. Sometimes the customer is a different facility of the same firm or a business partner at some other location in the supply chain. For example, the logistics manager of a Wal-Mart warehouse would think of the Wal-Mart retail location as its customer. They may be part of the same overall organization, but one serves the other as its customer.

FIGURE 4.3 Traditional view of the “customer.”

Within the supply chain context there is a broad perspective of the term “customer.” The total supply chain looks at the end user of the product or service as the primary customer whose needs or requirements must be accommodated. The supply chain perspective, however, recognizes that the supply chain is made up of intermediate organizations, from raw material suppliers at the beginning of the chain to final consumers at the end of the chain. Each organization in the chain is dependent upon the organization that immediately precedes it in the chain and serves as its supplier. Therefore, all organizations in the supply chain are both suppliers and customers to other members of the chain. For example, Wal-Mart may sell Tide laundry detergent to the final customer in the supply chain. Proctor & Gamble (P&G) provides Tide laundry detergent to Wal-Mart and is therefore its supplier. However, P&G is a “customer” to their suppliers from which it receives supplies such as chemicals and plastics. Therefore, Proctor and Gamble is a “customer” of its suppliers and a “supplier” to retailers such as Wal-Mart. Although each entity in the chain serves their immediate customer they are ultimately driven by the demands of the final customer in the chain. This is shown in Figure 4.4.

TYPES OF CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIPS

The traditional marketing approach has been to pursue a strategy of increasing the number of customer transactions in order to increase revenues and profits. This is transactional marketing as it focuses primarily on increasing the number of customer transactions. This type of relationship does not consider the long-term impact that comes from building alliances. Rather, it is only a short-term view of the supplier-customer relationship. Often this strategy is used together with the marketing practice of developing target markets, such as grouping customers based on demographics or buying patterns. Usually these groupings are very large and specific customer needs are neglected. Three of the most common strategies used to satisfy customers in various target markets are the following: standardized strategy, customized strategy, and niche strategy.

FIGURE 4.4 Every supply chain member is both a supplier and customer.

MANAGERIAL INSIGHT'S BOX— UNDERSTANDING THE CUSTOMER

Keurig Versus Flavia

Keurig and Flavia are the Coke and Pepsi of office coffee and have equally dominated this market for nearly a decade. Flavia had 362,500 systems in place in the United States, whereas Keurig had 378,420. They are both focused on becoming a leader in the office coffee market. They understand that their customer is corporate America not the home market, and have designed their products and supply chains accordingly.

Keurig uses pods, or K-cups, that include nitrogen-flushed real ground coffee from brands such as Newman's Own and Wolfgang Puck. Flavia, owned by Mars, uses packets of liquid-coffee concentrate and offers 35 flavors. Each requires machines specialized for the pods. They are expensive and accommodate single-serving use on a large scale, inappropriate for the home consumer.

Flavia claims advantage over Keurig's pods, claiming that with their product there is no danger of the “cross-contamination,” which can occur with mass use. This is where coffee residue, for example, may contaminate a subsequent brewing of green tea. Unlike Keurig's, the content of Flavia's packets never touch the machine. Both claim superiority on the convenience front for the office market—Flavia by offering independent packets of milk, whereas Keurig offers pods containing milk and coffee together. A more insidious selling point is that with Flavia there's no worry about employees swiping K-Cups for their home machines.

While Keurig and Flavia fight each other, some companies are discussing a “post-pod” future in the office coffee market. A better alternative for this type of “customer” may be devices that use “greener,” more cost-effective methods for making single serving coffee, such as the Starbucks Interactive Cup Brewer. In the end it will depend on what the customer wants. However, it requires an understanding of the needs of the office customer—cost-effective, single serving, mass customization—which is different from the home customer.

Adapted from: “Single-Serve Showdown.” Bloomberg Businessweek, June 21, 2010.

In the standardized strategy all customers are viewed in the same way. It provides a minimal amount of product customization. When market segmentation is used it ultimately averages out the needs of all the customers in the group. The company then develops products to satisfy the needs of the average of the customers in the group, rather than satisfying individual customer needs. This has large cost advantages in that all processes from manufacturing, logistics, and marketing are streamlined and predictable. The advantage is that the customer receives a product at the lowest cost possible.

However, many customers may not be satisfied under this strategy as they are unable to receive the products that meet their specific needs. There are many examples of “one-size-fits-all” products. For example, the pain reliever acetaminophen, sold under the brand name of Tylenol, was historically available only as a standard pain reliever. However, it is now available in many versions, including sinus-relief Tylenol, Tylenol PM, and Tylenol tablets versus gel-caps. This has provided greater options, but has also increased supply chain costs.

Customized strategy is a differentiated strategy that capitalizes on information that comes from market segmentation and target markets. The strategy enables the company to develop different versions of a product based upon specific market needs. This results in higher priced products due to the complexities involved in producing and coordinating multiple products being sent to multiple locations. Differences occur in the manufacturing process, distribution channel, logistics, and marketing. For example, Coca-Cola is an agile company that changes features of its product to meet different markets. Product sizes are smaller in the Asian and European markets. Also, the company has moved to producing various juice drink alternatives and teas, particularly popular in the Asian market, as opposed to colas.

The niche strategy is a strategy that targets only one segment of the overall market by offering very precise products that specifically meet customer needs. It is the opposite of the undifferentiated strategy. This is typically a strategy exploited by small firms or new companies. For example, there are many specialty retail stores that target niche markets, such as maternity clothes, or suits for tall men, or petite women. These companies are smaller and offer products at higher prices to compensate for the greater customer focus of their offering.

The ultimate in customer relationship management is to focus on each individual customer and to design a product to meet their individual needs. This approach is called micro-marketing or one-to-one marketing, and recognizes that each individual customer may have their own unique requirements. This could be an end-customer such as an individual, or an intermediary customer such as a manufacturer or retailer. For example, large suppliers to Wal-Mart are required to develop information systems that directly match those of Wal-Mart to provide seamless information transfer.

One-on-one relationships may not be feasible with every customer. Also, many customers may not care for a customized relationship and may prefer a standardized product at a lower cost. However, one-to-one relationships can significantly reduce transaction costs between supply chain intermediaries by making transactions routine and ultimately lowering cost for the end customer. One-to-one relationships with the end-customer can also be a significant factor in building brand loyalty.

Today, a high degree of one-to-one customization has been made possible with the development of customer relationship management (CRM) software that focuses on the interface between the firm and its customer. These systems collect customer-specific data, which allow the firm to provide customer-specific solutions. We look at these systems in more detail next.

MANAGING CUSTOMERS USING CRM

CRM involves managing long-term relationships between the company and its customers in order to improve profitability. It is a concept that has gained great popularity over the past few years given the advances in technology and the tremendous benefits it provides to the company and the supply chain.

To keep customers coming back firms must offer distinct capabilities that provide value to customers. We know that in general terms customers perceive value through reliable, on-time delivery of high-quality products and services at competitive pricing. The problem, however, is that today's customers demand a greater amount of customization than ever before. Companies have to work hard to identify very precise needs of each customer group.

The ability to capture detailed customer information has become a reality with today's sophisticated technology. CRM uses automated customer transactions to gather data and customize communication. This data is captured through suites of software modules that are part of larger enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. They collect information through automated transactions in order to create large databases that, in turn, can be mined to design customer-specific solutions. For example, American Airlines uses CRM applications to precisely identify their most profitable customers. This information is then used to build strong customer relationships. One example of this might be sending a personalized text message to a highly valued customer that their planned flight is going to be delayed.

The advantage of CRM is that it provides information that aids market segmentation as we can better create clusters of customers based on profitability and other factors. It also helps to predict customer behavior and create customized customer communication. Therefore, CRM plays a critical role in SCM.

DELIVERING VALUE TO CUSTOMERS

VOICE OF THE CUSTOMER (VOC)

The central focus of supply chain management is to create value for the customer. However, how can we create value if we don't know exactly what the customer wants? The key issue is to understand exactly what it is the customer perceives as value. This is the responsibility of marketing and is not as easy as it sounds.

Understanding what the customer wants and perceives as value is a complex process. Most customers have a difficult time defining value, but they know it when they see it. For example, although you probably have an opinion as to which cell phone provider provides the highest value it may be difficult for you to define the specific standard of value in precise terms. Also your friends may prefer a different cell phone provider as they have a different opinion regarding what constitutes value.

Voice of the customer (VOC) is the process of capturing customer needs and preferences. Customer needs can be broken into three levels: basic needs, performance needs, and excitement needs. Basic needs are minimum customer expectations that are understood. If these needs are not met the customer would be extremely dissatisfied. For example, brand new rain boots that leak in wet weather would be considered unacceptable. Performance needs differentiate one product from another relative to the prices. An example here may be finding two pairs of rain boots at a comparative price, but one has a skid-proof sole. Excitement needs are normally not known by the customer in advance, but they elicit delight over the product. An example here may be purchasing the boots and finding that there is a free 10-year replacement guarantee for any dissatisfaction. Understanding different types of needs is critical information in designing products and services, and their associated supply chains.

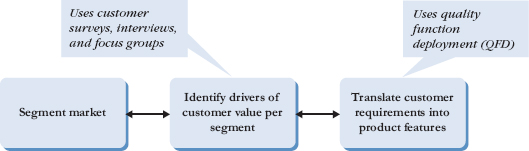

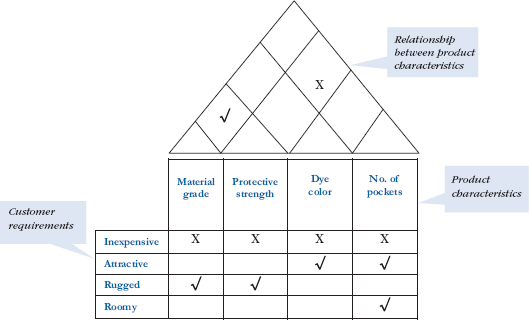

The definition of value depends on the point of view of the customers defining it. In the rain boots example, the definition of value would be different if the customer was a parent buying rain boots for their child versus a fire fighter buying waterproof boots for work. For this reason, VOC begins by dividing customers into their market segments. As we discussed earlier, we can segment customers by their demographic features or how, where, and when they use the product. This marketing information can help focus our attention on critical customer requirements in each market segment. After market segmentation, market research is used to gather information from customers in each segment using a variety of tools, such as interviews and focus groups. This enables marketing to identify key drivers of value in each market segment. Finally, the last step in translating the VOC is to use a tool called quality function deployment (QFD) to translate general customer requirements into specific product characteristics. These steps are shown in Figure 4.5.

QFD is a tool for translating the voice of the customer into specific technical requirements. Customers often speak in everyday language. For example, a product can be described as “attractive,” “strong,” or “safe.” To produce a product the customers actually want, these vague expressions need to be translated into specific technical requirements. This is the role of QFD. QFD is also used to enhance communication between different functions, such as marketing, operations, and engineering.

FIGURE 4.5 Translating the voice of the customer.

Figure 4.6 shows a simplified example of a QFD matrix for a laptop computer bag. This matrix is sometimes called the “house of quality,” as it resembles a picture of a house. The left side of the matrix lists general customer requirements that marketing gathers from customers using tools such as interviews or focus groups. The customers may say they want the computer bag to be inexpensive, attractive, rugged, and roomy. Along the top of the matrix is a list of specific product characteristics. The main body of the matrix shows how each product characteristic supports the specific customer requirements. For example, “rugged” is supported by material strength and grade. Finally, the “roof ” of the matrix shows the relationship between some of the features. Strength of material and grade go together, whereas more compartments may take away from the bag's protective strength. The QFD matrix moves the organization from these general customer requirements to specific product characteristics. It can also show where conflict may exist between some of the features and where trade-offs may have to be made.

FIGURE 4.6 A simplified QFD matrix for a laptop case.

WHAT IS CUSTOMER SERVICE?

Today's customers are very different from those just a few years ago. They demand higher performance standards than ever before and brand loyalty is not necessarily something that they routinely support. They expect high-quality and low-cost products delivered at their convenience. The problem is that these competitive dimensions can easily be copied by competitors. Excellence on these dimensions is expected but does not necessarily provide a competitive advantage. The one competitive dimension, however, that is difficult to copy and can provide a competitive advantage is customer service. As a result, many companies have made customer service their focal point and the driving force of their supply chains.

Customer service can be defined as a process of enhancing the level of customer satisfaction by meeting or exceeding customer expectations. It can provide a competitive advantage to the firm and the supply chain by maximizing the total value to the final customer. Within an organization customer service can be viewed in three distinct ways, each requiring progressively more commitment. They are:

- An Activity. This first view looks at customer service as an activity that a firm must do in order to satisfy customers. This includes activities such as billing and invoicing, product returns, and handling claims. Companies with this view believe they are meeting their obligations by having a customer service department responsible for handling customer problems and complaints.

- A Set of Performance Measures. This second view looks at customer service in terms of specific performance measures that must be met. Examples would be percentage of orders delivered on time or the number of orders processed within acceptable time limits. A company with this view would consider it has met its customer service requirements if the performance measures were being met.

- A Philosophy. This last view looks at customer service as a firm-wide commitment to customers through superior customer service. It is a philosophy that permeates all decisions throughout the company. This view of customer service is consistent with the emphasis on today's quality management, which we discuss in Chapter 10.

The first view of customer service looks at it as a mere activity and requires the least amount of involvement on the part of the company. From this perspective, customer service activities are at the transactional level. For example, the activity of accepting product returns from customers in a retail store adds no value to a product. The activity is merely a transaction to please customers. Companies with this view of customer service have only a limited opportunity to add value to the customer.

The second view of customer service provides an objective way of measuring customer service performance and can serve as a benchmark to gauge improvement. However, it is not sufficient to create customer service excellence. Customer service needs to be an organizational philosophy in order to provide a competitive advantage.

IMPACT ON THE SUPPLY CHAIN

Customer service excellence can provide a competitive advantage. However, it requires commitment of the entire supply chain and can be costly to implement. Supply chain managers have to balance the benefits attained from increased customer service levels against the cost of providing that service. Consider, for example, a retail customer that can lower their inventories if their supplier uses air rather than truck transport. The customer can lower inventory costs as a result of shorter transit time. However, higher transportation costs are going to be incurred as air transport is costlier than transport via truck. Supply chain managers have to find the optimum balance of these costs.

Customer service impacts the supply chain on four dimensions: time, dependability, communications, and convenience. Let's look at these in a little more detail.

- Time. Time is concerned with the speed at which the company responds to its customers. From a supply chain perspective this refers to the time to complete an order and deliver it to the customer, called the order cycle time. Competition based on time has been primarily enabled by the function of logistics, which today has the ability to guarantee a given level of order cycle time. Successful logistics operations have a high degree of time control over the elements of moving goods through the chain, such as order processing, order preparation, and order shipment. By effectively managing these activities, companies have ensured that order cycles will be responsive and of short duration.

- Dependability. Dependability refers to consistently meeting promises made to customers, including order cycle time and level of quality. In fact, for some customers dependability can be more important than delivery time or other dimensions. For example, some customers might prefer a longer lead time, knowing with certainty the exact time of delivery. This allows customer firms to minimize their inventory levels if lead time is consistent. A company that knows with certainty that lead time is going to be 10 days can make better plans than being promised a shorter lead time with the possibility of fluctuation. This level of dependability translates into carrying less inventory as safety stock and results in lower costs.

- Communication. Communication is an aspect of customer service that involves providing real time order status to all supply chain customers. Communication with customers is vital to monitoring customer service levels relating to dependability. It involves integrated information technology (IT) across the supply chain that tracks the order filling process and is enabled by communication tools such as electronic data interchange (EDI) or the Internet. In addition to providing status update, these communication tools can reduce errors in transferring order information as the order moves through the chain. The simplification of product identification is one strategy companies use to make this process more efficient. One example of this is using product codes to reduce order picker errors.

- Convenience. Companies are offering more customer conveniences as they move toward providing a greater amount of customization to their customers. In turn, this requires that the supply chain be more flexible to accommodate a range of requirements. The simplest option is to have one or a few standard service levels that apply to all customers. However, this is only possible when the requirements are the same for all customers. For example, one customer may require the supplier to place all products on pallets and ship everything by rail. Another customer may require truck delivery only, using no pallets. Some customers may require special delivery times that must be met. This all places large demands on the supply chain and especially the logistics function. It also impacts decisions regarding packaging, mode of transportation, and routing.

One strategy to deal with this problem is to group customer requirements by factors such as customer size, market area, and the product line the customer is purchasing. This grouping, or market segmentation, makes it easier to meet customer expectations economically.

MEASURING CUSTOMER SERVICE

Developing and measuring standards of customer service performance is essential as it allows a company to monitor how it is doing in meeting set objectives. The company can also benchmark its performance against others in its industry.

Historically, companies used measures that viewed performance from the perspective of the supplier, solely focusing on customer service dimensions prior to shipping. This did not permit the supplier to know whether the customer was satisfied and if there were any problems with the delivery. Also, these measures did not enable the seller to identify whether there were any problems and whether its improvement efforts were successful.

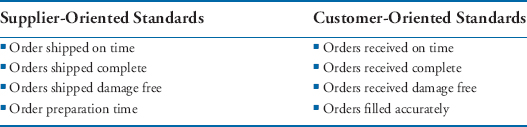

FIGURE 4.7 Supplier-oriented versus customer-oriented standards.

Effective performance measures focus on customer service from the viewpoint of the customer rather than the supplier, as shown in Figure 4.7. These measures provide the data to make an evaluation of how successful the product delivery system is. They can also serve as an early warning system of potential problems as they develop. For example, monitoring customer service delivery may show that on-time delivery has slipped from 99% to 95%, triggering the company to evaluate the system for potential problems. In fact, the on-time delivery measure is particularly important in supply chain management as it has become common practice for buying companies to give specific delivery appointment times for deliveries. The move to lean supply chain systems, which we discuss in Chapter 10, requires a very narrow delivery time “windows” for suppliers and has made achieving on-time deliveries much more difficult than in the past.

Most companies, however, do not rely on one, but multiple measures of customer service performance. Using multiple measures enables a company to address potential problems on many customer service dimensions. Having multiple performance measures, however, can make it even more difficult to achieve high levels of customer service.

GLOBAL CUSTOMER SERVICE ISSUES

Companies that take a global view of customer service find that it adds even more complexities. Rather than dividing world markets into separate entities with very different product needs, as might be expected, a better approach is searching for common market demands worldwide. Different parts of the world have different service needs that are related to issues such as information availability, order completeness, and expected lead times. Other factors that contribute to differences in customer service are the availability of a supporting infrastructure, such as roads, power, communication network, the local congestion, and time differences. These factors may make it impossible to achieve the same levels of customer service globally.

Global customer service levels should be designed to match local customer needs and expectations to the greatest degree possible. A strong argument can be made for the implementation of a centrally coordinated global supply chain strategy. However, the one activity that should be conducted locally is setting the customer service standard.

GLOBAL INSIGHTS BOX—GLOBAL CUSTOMER SERVICE

Coca-Cola

Most global companies typically provide different levels of customer service based on location. An example is Coca-Cola, which provides very different types of service in Japan than in the United States or Europe. For example, in Japan the company provides a much higher level of service to its retail customers and merchants, but it meets local standards. The drivers of Coca-Cola delivery trucks are responsible for providing merchandising in supermarkets, helping in processing bills in small mom-and-pop operations, and responding to signals from communication systems in vending machines so that time is not wasted delivering to full machines. Developing the service to match the needs of the country creates the most efficient and effective customer service policy, rather than simply implementing the same strategy worldwide.

CHANNELS OF DISTRIBUTION

WHAT ARE CHANNELS OF DISTRIBUTION?

A channel of distribution is the way products and services are passed from the manufacturer to the final consumer. It is made up of the entities involved in getting products and services to final customers and can involve a variety of intermediary firms, including wholesalers, distributors, or retailers. Decisions regarding the distribution channel are critical to a company's success as they are directly related to the ability for the organization to access the final customer.

Channels of distribution can be classified as either direct or indirect. A direct channel structure is one where the transaction is directly from the producer to end-user or final consumer. An example might be a farmer that sells directly to the final consumer, as at a farmers market. Another example is the sale of jet aircraft that are custom designed and sold directly to the airline. This channel usually gives the company greatest control as to how the product is being designed for the final customer. However, distribution costs incurred by the manufacturer are higher, making it necessary for the firm to have substantial sales volume, market concentration, or higher product cost.

Indirect channels are those that use intermediaries, such as wholesalers and retailers, to sell to final consumers. In this case the external institutions or agencies (e.g., carriers, warehouses, wholesalers, retailers) assume much of the cost, burden, and risk. The manufacturer receives less revenue per unit than with the direct channel, but it also carries lower risk.

There is no “best” distribution structure. Rather the best distribution channel structure varies by the nature of the product and the market. The structure design depends on numerous factors, such as buying patterns of end customers, competitors, and market saturation. Characteristics of the product itself are another important factor. Complex products, for example, may require a demonstration, which implies that they may need to be sold directly to the consumer. An example is the Kirby vacuum cleaner, which is sold by distributors directly to consumers with in-home demonstrations. Difficult to move products may be sold through an intermediary, such as automobiles that are shipped directly to dealers. Many products are shipped through wholesalers who may be better equipped to efficiently combine products from many different suppliers. Sometimes agents may be involved that negotiate between manufacturers, distributors, and retailers.

Most companies want to identify a “best” channel structure, but there is no “best” channel structure for all firms producing similar products. Management must determine the channel structure that is appropriate given the firm's corporate and marketing objectives. For example, if the firm has targeted multiple market segments then management may have to develop multiple channels to service these markets efficiently. The distribution channel selected has important policy implications for the organization. Consider that direct-to-customer strategy is the model historically used by Dell. However, recently Michael Dell announced that Dell Computer Corporation would be changing its distribution channel to sell through retailers such as Best Buy. This change in Dell's distribution strategy is in response to changing markets and shows the importance of changing distribution channels based on the business environment.

DESIGNING A DISTRIBUTION CHANNEL

The theory of channel structure was first developed by Louis P. Bucklin, who explained that the purpose of the distribution channel is to provide consumers with the desired products and services at minimal cost. The best channel structure forms when no other channel generates more profits or provides greater consumer satisfaction per dollar of product cost. According to Bucklin, to achieve the optimal channel structure, functions over time shift from one channel member to another in order to improve delivery and cost. As a result, channel structure is not static but is constantly changing to meet customer demands. Given a desired product and service combination by the consumer, channel members arrange their functional tasks in a way that minimizes total channel costs. As specific functions shift along the channel there may addition or deletion of channel members. Although organizations design channel structures taking into account many factors, it is consumers who ultimately determine the channel structure through their purchasing patterns.

There are three factors that influence the structure of the distribution channel. These are: market coverage objectives, product characteristics, and customer service objectives. The first of these, market coverage objectives, involve decisions regarding the size of specific market areas and the intensity of coverage of specific geographic regions. For example, this could be measured by the number of retail outlets in a particular region relative to the concentration of customers.

Three basic market coverage alternatives exist. The first alternative is intensive distribution. This involves the placement of a product in as many outlets or locations are possible. An example of this would be a product, such as Tide laundry detergent, that is available at almost all supermarket locations. The second market alternative is selective distribution. This involves the placement of a product or brand in a more limited number of outlets within a specific geographic area. Last is exclusive distribution, which involves placement of a brand in only one outlet in each geographic area. Exclusive distribution is an alternative that should be related to the types of customers the company wants to serve.

Product characteristics are another significant factor in the design of the distribution channel. For example, one important characteristic is the value of the product. High-value products typically require a shorter supply chain to minimize cost, whereas low-value products should have intensive distribution to maximize sales. Highly technical products usually require product demonstration and are better suited for a direct channel. Highly perishable products need to be delivered to markets fast due to their short life cycle.

Customer service objectives are another consideration in designing a channel structure. Customer service is used to differentiate the product or influence the market price, provided that customers are willing to pay more for better service. In addition, the supply chain structure determines the costs of providing a specified level of customer service. This means that customer service levels and the design of the appropriate distribution channel should carefully balance customer needs and costs.

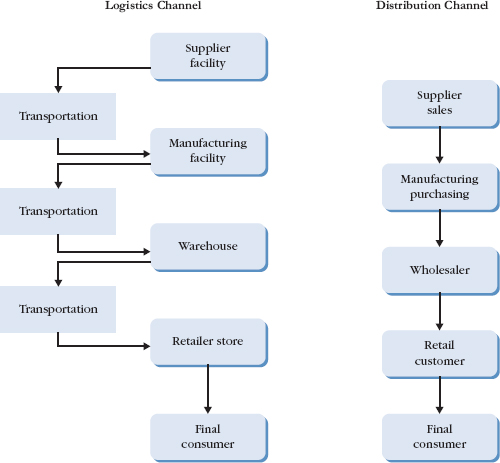

DISTRIBUTION VERSUS LOGISTICS CHANNEL

The distribution channel is different from the logistics channel. However, the logistics channel and the distribution channel are interrelated and are both part of the supply chain. These channels are illustrated and compared in Figure 4.8.

MANAGERIAL INSIGHTS BOX—CHANGING THE DISTRIBUTION CHANNEL

Steinway Pianos

When Bruce Stevens joined Steinway & Sons as CEO in 1985, the maker of legendary hand-crafted pianos found itself in the middle a slowdown crisis. Sales had slowed dramatically and excess inventory was clogging the sales channel. In fact, the company had over four months worth of finished goods inventory—over 900 unsold pianos—just sitting in inventory. Its 150 authorized dealers were complaining about low profit margins and the costs associated with supplying concert pianos for Steinway Artist performers. The company was clearly in trouble.

The dealers were critical to Steinway's success. They were the ones that represented the company through trained salespeople, beautiful showrooms, and good displays. To understand their concerns, Stevens spent six months visiting the discontent dealers across the country and listening to their concerns. Based on what he heard he developed a relationships plan with dealers called the “Steinway Working Partnership.” At the core of this program was an offer to provide expanded and exclusive territories to dealers, as well as profit opportunities in exchange for their stepped-up commitment to display and promote Steinway products. Many dealers were reluctant to make the required investment. It required upgrading showrooms, increasing inventory, and adding salespeople, while sales were running at 20% below average.

The dealer network was slowly trimmed. The dealers that remained saw Steinway making good on its promises of expanding territories and they signed on to the program. By 2009, only 63 dealers remained in Steinway's U.S. dealer network, less than half of the mid-1980s level. However, those remaining dealers were far more profitable. It took the company almost six years to gain the trust needed to fully implement the program, but it was a big success for Steinway and the dealers that remained.

For Steinway, downsizing the distribution channel was the best way to increase dealer profitability and sales for the company. Rather than waiting and reactively managing its distribution channel, Steinway proactively pruned the channel to make it stronger.

Adapted from: Johnson, M. E., and R. J. Batt. “Channel Management: Breaking the Destructive Growth Cycle.” Supply Chain Management Review, 13(5), July 2009: 26.

The logistics channel refers to the physical movement of products from where they are available to where they are needed. The distribution channel, on the other hand, refers to the transactional entities involved, such as dealers, distributors, and wholesalers. Consider that a “warehouse” is part of the logistics channel, whereas a “wholesaler” is part of the distribution channel. The wholesaler may not even hold the actual product in the warehouse but may simply serve as an agent between the manufacturer and retailer. Successful supply chain management requires proper management and integration of both types of channels.

FIGURE 4.8 Logistics versus marketing distribution channel.

THE IMPACT OF E-COMMERCE

The Internet has provided unprecedented ability for companies to access massive numbers of customers across the globe. However, this broad reach must be coupled with a suitable distribution network to fulfil orders that are placed over the Internet. E-commerce can provide success to a firm only if the firm can integrate the Internet with existing channels of distribution in a way that uses the strengths of each appropriately. There are numerous examples of companies that have created an online presence but subsequently failed due to the inability to integrate it with the physical channels. One example was Kozmo.com, a web-based home delivery company founded in l997. Kozmo's mission was to deliver products to customers—everything from the latest video to ice cream—in less than an hour. Kozmo was technology enabled and rapidly became a huge success. However, the initial success gave rise to overly fast expansion. The company found it difficult to coordinate the physical distribution channel with the promises made on its website. The consequences were too much inventory, poor deliveries, and losses in profits, and they had to close their doors in April 2001.

The coupling of the virtual network with the physical network has been referred to as “clicks and mortar.” The success of an e-business is closely linked to the distribution capabilities of the existing supply chain. Separating them typically adds to inefficiencies.

A company needs to find ways to use its physical assets to satisfy both online orders and customers who want to shop through traditional routes for the most effective way to integrate e-business within its supply chain network.

E-commerce has created other challenges for companies. For example, shipping small bundles of products to many different customers is very different than shipping in bulk to one location, such as a retailer warehouse. Often companies underestimate and do not adequately calculate shipping costs. For example, it is not a good option for companies to charge standard shipping fees without consideration of size, weight, and destination. Otherwise they will incur losses. Many e-businesses have incurred financial losses due to incomplete consideration of shipping costs. Companies must have an accurate assessment of the costs incurred to fulfil an order and reflect this cost in the prices they charge.

The e-commerce distribution system should also be modified to accommodate shipping of small bundles. E-business has required a change in distribution from shipping large quantities to retail locations to shipping small packages to individual customers. For example, “bricks-and-mortar” bookstores, such as Borders, send all their merchandise in large quantities to replenish their stores. In contrast, online booksellers must send small packages to individual customers that may contain only one or two books. This can prove to be very expensive from a distribution point of view. Therefore, it becomes critical for companies to exploit every possible opportunity to consolidate shipments in order to lower costs. This may involve partnering with other firms to consolidate shipments. To increase consolidation and reduce transportation costs, e-businesses must try to bundle an entire customer order into a single package.

Recall that handling returns is a critical part of the supply chain. As a result, the distribution channel should be designed to efficiently handle returns. Customers purchasing products online are likely to have a higher rate of return than customers purchasing from a physical store due to their inability to physically handle the product beforehand. Regardless of how good a website is, it cannot match the customer experience of touching and seeing the product at a retail store and the product purchased online is often different from the customer's expectation. Handling returns is a big challenge for e-businesses and can have a strong impact on customer satisfaction. Customers are more likely to shop from e-businesses that make returns easy.

A strategy that has worked well for successful e-businesses is to have the retail locations handle the returns by allowing customers to return unwanted merchandise at a store. Pure e-businesses that do not have a “bricks-and-mortar” location, however, have no other choice but to allow customers to mail back the unwanted merchandise. The easier the return process for customers, such as providing pre-printed return labels, the higher the supply chain cost to the company. On the other hand, the more difficult the process, the less satisfied the customer will be and the more reluctant to purchase online in the future.

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS

- Marketing is the function responsible for linking the organization to its customers and is concerned with the “downstream” part of the supply chain. It is responsible for identifying customer needs, determining how to create value for customers, and building strong customer relationships.

- Marketing decisions drive all actions of the organization and the supply chain. These decisions fall into four distinct categories known as the marketing mix or the 4Ps. They are: product, price, place (distribution), and promotion.

- The traditional marketing approach has been to pursue a strategy of increasing the number of customer transactions in order to increase revenues and profits—transactional marketing. Today's approach to marketing is to develop long-term relationships with customers—relational marketing.

- CRM is sophisticated technology that gathers data and customizes communication from automated customer transactions. This data is captured through suites of software modules that are part of larger enterprise resource planning systems (ERP).

- Customer service is the process of enhancing the level of customer satisfaction by meeting or exceeding customer expectations. It can be viewed in three distinct ways: an activity, a set of performance measures, and an overarching philosophy.

- A channel of distribution is the way products and services are passed from the manufacturer to the final consumer. It is made up of the entities involved in getting products and services to final customers and can involve a variety of intermediary firms, including wholesalers, distributors, or retailers.

- Channels of distribution can be direct or indirect, and are part of the overall supply chain.

- E-commerce requires changes in the channel of distribution through changes in pricing structure, shipping small bundles, and handling returns.

KEY TERMS

- Market segmentation

- Mass marketing

- Target marketing

- Transactional marketing

- Relational marketing

- Product

- Price

- Place

- Promotion

- End consumer

- Organizational end user

- Standardized strategy

- Customized strategy

- Niche strategy

- Micro-marketing

- One-to-one marketing

- Customer relationship management

- Voice of the customer (VOC)

- Quality function deployment (QFD)

- Customer service

- Channel of distribution

- Direct

- Indirect

- Intensive distribution

- Exclusive distribution

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Describe the differences between transactional and relational marketing. Provide an example from your own life where you have encountered them. How did each make you feel as a customer?

- Find an example of a product where you felt there were too many product choices. Explain the implications for the company and their supply chain.

- Identify a product market that is currently experiencing changes in customer preferences. How are the companies in that industry responding to the changing preferences? What are the supply chain implications?

- Identify a product currently marketed for household use. Imagine you were asked to market the product for commercial use. How might the product characteristics change and what would be the impact on the supply chain?

- We all encounter CRM in our everyday lives—from our purchases at the grocery store to our online searches. Provide examples from your everyday life where companies were able to gather information about your consumer preferences.

CASE STUDY: GIZMO

Orange Company was based out of Southern California and was doing remarkably well considering that only 10 years earlier the company had been merely a hobby for Sam Wilkerson. Sam was fascinated by taking apart computers, adding memory, then putting them back together. He never expected that his weekend hobby would turn into one of the highest earning computer companies in the world. The company's relaxed atmosphere encouraged creativity and product innovation. The developers were never afraid to try something new. In fact, it was one of these highly experimental projects that led to their newest product: a smart phone that can do it all—simultaneously surf the Internet, text message, do voice recognition note taking, play music and movies, while still maintaining superior functioning for making telephone calls. With no buttons to get in the way, only a touch screen, it was unlike anything seen on the market.

While the management at Orange felt that their new smart phone—named Gizmo—would be well-received by consumers as innovative and cutting edge, they had concerns. They were not sure about their target market, the marketing strategy, and the resulting supply chain implications. These decisions were directly tied to their pricing strategy and had capacity and delivery implications. Who would be their target market and how would they price the product given its abundant features? Should the product be targeted to business professionals or students or the public in general? If the Gizmo did significantly better than expected, could their supply chain handle the added demand?

Orange was considering partnering with the largest mobile service provider in the industry, Random Wireless, for exclusive distribution. This would mean that they could utilize an already established distribution channel for their first smart phone release. Orange believed that this would mean significant distribution savings and the ability to reach a wider market. They would also be able to provide service support at many locations. However, there were also disadvantages to going through one exclusive distributor.

Orange knew that they had a wonderful product but the key to success would be good marketing, an excellent distribution network, and a reliable supply chain. They had some decisions to make.

CASE QUESTIONS

- Identify at least two different possible target markets for the Gizmo. How would the marketing strategy differ for each target market? How would the pricing strategy change and the volume sold? Identify the supply chain implications for each target market.

- If Orange decided to go after multiple market segments, identify the supply chain requirements. Should they have multiple supply chains?

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages to going with one exclusive distributor. How would this decision be affected by the selection of target market? What would be the implications on the supply chain? What would you do if you were Orange?

REFERENCES

Bucklin, Louis P. A Theory of Distribution Channel Structure. Berkeley: University of California, Institute of Business and Economic Research, 1966.

Fugate, Brian, and John T. Mentzer. “Dell's Supply Chain DNA.” Supply Chain Management Review, October 2004: 20–25.

Kotler, Philip, and Gary Armstrong. Principles of Marketing, 12th edition. Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2008.

Liker, Jeffrey K., and Thomas Y. Choi. “Building Deep Supplier Relationships.” Harvard Business Review, December 2004: 104–113.

Stock, James, and Douglas M. Lambert. “Becoming a ‘World Class’ Company with Logistics Service Quality.” The International Journal of Logistics Management, 3(1), 1992: 73.

Williams, Alvin J. “Innovations: Branding Your Supply Chain.” Supply Chain Management Review, October 2004: 60–63.