Cities are without a doubt one of the main channels to achieve sustainable development and economic and social growth. Yet cities are also the cause of many economic and social problems (European Union 2011). For example, while the contribution cities make to the gross domestic product (GDP) is typically very high, many cities suffer from severe unemployment and poverty, which can sap their resources and become a drain on their respective countries. Likewise, while cities typically contribute markedly to the art and other cultural assets of their respective countries—cities usually house a variety of museums, galleries, theaters, and art schools—the related cultural activities are often led by very small and close-knit groups of people and organizations, and therefore, they are not always accessible to all the city’s residents and visitors. At last, although many cities in the world have taken the lead with respect to issues of environmental quality, developing and advancing many important programs and projects in the field (Portney 2005; Lehmann 2010), cities are simultaneously responsible for high share in the amount of pollution generated, due, for example, to greenhouse gas emissions and garbage production. City planning and growth efforts, therefore, should aim for greater alignment between the city’s problems and their solutions.

At their most basic level, cities are also spaces of services. In fact, all city activities can be defined as the exchange of services between a wide variety of stakeholders—namely, residents, traders, visitors, and city authorities (Frug 1998; Miguel, Tavares, and Araújo 2012). Therefore, the challenging question is, how do we define a city from a sustainable services perspective, and to what does that definition refer?

Types of City Services

City or municipal services usually refer to the services that city authorities provide mainly to the city’s residents. Yet cities typically offer numerous additional types of services that are produced, delivered, and used in the city by a variety of other providers and customers who are not necessarily citizens of the city. In general, all the services provided within the city framework can be divided—based on the nature of the service, the provider, the customer, and the platform, or the infrastructure upon which the service provision is based—into four main categories.

1. Municipal services—Public services provided by city authorities via different bodies and systems, and services that, although privatized, are still supervised and controlled by the city (Joassart-Marcelli and Musso 2005; Kelly and Swindell 2002). These include services that support the supply of physical resources or tangible values, such as water and electricity supplies and sewage removal, or intangible values such as governance, education, health, and welfare services.

2. Community services—Not-for-profit public services, from military service to soup kitchens, provided by individuals or by groups of people for benefit of the greater public (Youniss et al. 1999).

3. Private services—Provided by the private sector, individuals, or companies, private services span the entire spectrum of services, from food and clothing shops to medical services to equipment repair services.

4. Ecosystem services—Natural services ranging from temperature control and disease control to waste decomposition and human inspiration (Gretchen 1997).

The growing number and diversity of services provided by cities have elicited the need to integrate city services not only to optimize their provision and maximize their quality, but also to ensure their sustainability. In so doing, the local and global effects of services must be considered in the short and the long term. In the urban framework, sustainability refers to the integration of all the components and dimensions of the totality of urban activities and services to enable all stakeholders, including future generations, to enjoy high-quality life. Essential to this notion of sustainability is the continuity and prosperity of ecosystems over time, which can only be realized by limiting—or, ideally, preventing—damage to both the natural and the social environments that are integral to the city’s existence (Davies et al. 2011; Zang, Wu, and Na 2011).

As mentioned previously, under the auspices of urban sustainability, local authorities around the globe are embracing new urban models—e.g., green city, ecocity, resilient city, or smart city—to cope with today’s modern urban challenges. Both the green city and the ecocity concepts usually describe the rational use and regeneration of resources while reducing pollutant emissions and maintaining the health of both the social and the natural environments. Improving on that definition, the notion of a resilient city refers to the ability of a city to adapt to changes while providing the resources needed by its current inhabitants without infringing on its capacity to deliver the same resources to its future inhabitants. The resilient city thus maintains its “competitive edge,” which facilitates the city’s continued prosperity as a living space and as a place for business and leisure. Integrating these concepts into a comprehensive framework, the smart city combines information and communication technologies with sustainable urban development. But the management, planning, development, and operation of sustainable urban environments centered on the interplay between both the human and physical environments and the natural and built environments must reinvent how services are delivered and consumed within the city. Moreover, to address these challenges while considering sustainability as a service (Wolfson et al. 2010; Wolfson 2016), both the characteristics of a city and its physical boundaries must be redefined, and the different services of the city, as well as the role and responsibility of each stakeholder in their design and manufacture, must be identified and characterized. In short, to realize urban sustainability will require the redefinition of the city as a service-city.

The Service-City

Given the opportunity to create our cities from scratch, we would most likely build their physical structures and design their services using strategies markedly different from the less directed or conscious approaches used in the past. Yet because today few opportunities exist to build completely new cities, the trend in most of the world has been to modify current cities by enlarging them into megacities or metropolises. The service-city model, therefore, should be designed and developed from a perspective that considers the services and systems currently provided by the city while offering additional services that, together with existing services, are managed and operated using novel platforms.

Boundaries

The first step in designing the service-city model is to define its physical boundaries. A definition of the service-city’s boundaries, however, must consider the essence of services; namely, services are produced and delivered at a time and place where both the provider and the customer meet (i.e., service’s inseparability), and they are perishable and cannot be stored or reproduced in exactly the same way. From this point of view, the most straightforward definition of the service-city’s physical boundaries is the area where the services are provided and used. For example, corresponding to this definition, municipal services were traditionally produced and delivered within the physical boundaries of the city for its residents, who were the service’s main beneficiaries. The very nature of cities, however, dictates that some customers of a service are visitors from outside the city, and as such, they do not always use the service in the same place where it was provided. For instance, a patient who sees a doctor in a facility located in a certain city can act on the doctor’s advice in another place. In addition, a significant part of today’s marketplace is conducted in the virtual realm, where provider and customer typically do not meet in person, and they are not necessarily located in the same place. For example, a company’s call center can be situated in one location from where it provides a service to customers who reside elsewhere. In this scenario—where the delivery of the service is actually performed in two different places—the main question becomes, to which place is the service ascribed: to where it was produced or to where it was used?

The answer to this question, it seems, depends on the effects that the service has on each place, including economic effects, such as on economic growth and the labor market; social effects, such as on the community; and environmental effects, such as the service’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution and its influence on biodiversity. Provision of the service, therefore, may enhance the economic activity of the provider’s city, while the consumption of the service and its corresponding effects on the environment will be felt most strongly in the city where the customer resides. In this respect, every service delivery within the city’s physical borders, including services that were transferred using virtual tools (even if they were produced and used in two different places), constitutes a part of the city’s total services.

Provider and Customer

In general, everyone contributes in some way to the cocreation of city services. Therefore, the actors in the service system who play important roles include a variety of entities, which can be generally classified as providers, customers, city authorities, residents, visitors, and members of business from the private sector. More generally, the provider or the customer can also be a nonhuman entity, from nature to a computer and other instruments (owned and maintained by some responsible entity). In addition, for a variety of services, the customer may also simultaneously become a provider during the same service provision. Numerous smart-phone applications, for example, fall into this category: Moovit, a public transportation application that aims to help customers optimally satisfy their transportation needs, uses the information entered by each customer to update in real time the information it supplies to all of its customers, making that customer a provider of information to the service’s other customers. The potential variety and diversity of both providers and customers within the city poses a major logistical challenge. That challenge manifests in the organization and integration of all the relevant players and in the creation and support of a reliable and dependable platform that encourages the production and provision of both general and specific services. Furthermore, that platform should be accessible to, and fulfill the requirements of, every provider and customer.

Value

The value of a service can be initiated by the provider, the customer, or both. As such, the service can be oriented either in a top-down fashion, from the city to the resident and other stakeholders, or in a bottom-up scenario, from the residents or the private sector to the city or between a resident and a member of the private sector or between the residents themselves.

The service-city should comprise three different value provision models: (i) value in-exchange, which is value transferred from a supplier to a consumer; (ii) value in-use, which is value cocreated between a provider and a customer; and (iii) value in-return, which is value cogenerated by a provider and customer for other stakeholders. In addition, to sustainably provide all values (i.e., sustainable service), the economic, social, and environmental dimensions and effects of each service provision should be considered. In this respect, social values are those that account for justice, equity, and the stability of social order. Moreover, they should match the “needs” and “haves” not only of individuals, but also of communities. Economic value should consider the variety of economic models, such as cooperative and share economies, which, when incorporated into the local economy, function to strengthen it. Lastly, environmental value should extend beyond physical resource management and the use of cleantechs (Pernick and Wilder 2007) and CleanServs (Wolfson, Tavor, and Mark 2013a, 2014; Wolfson et al. 2015) to include a life cycle perspective and resiliency (i.e., sustainability cycle). Finally, the values that are provided in the frame of the service-city must permeate the entire value hierarchy—i.e., DIKIW: (Ackoff 1989; Spohrer, Piciocchi, and Bassano 2012)—from the collection of data to the processing of information into knowledge to the production of intelligent solutions that increase process efficiency and that eventually generate wisdom to increase effectiveness.

Whole or Holistic Service

Recently, the related concepts of whole and holistic service systems were introduced in the framework of service science in terms of service-dominant logic (Demirkan, Spohrer, and Krishna 2011; Spohrer 2011). A whole service can be defined as a service system or a service network that provides its customers with all the services they need—for example, a city, a luxury hotel, and so on. A closed service atmosphere, the whole service system facilitates, on the one hand, the rebuilding or the initial construction of a variety of entities, from cities to societies. On the other hand, it can also be used to preserve established values that may still have merit (Wolfson 2016). Insofar as it is equally applicable to the integration of environmental, social, and economic values within either existing or new networks, the whole service system is also the ideal framework within which to introduce sustainability as service.

Similar to the whole service model, the holistic service system can also support the entirety of people’s needs and provide them with all the tangible and intangible values they require or want. However, the boundaries of the holistic service system extend beyond those of the whole service system, as the former deals with both the efficiency with which the various services within the whole service system are provided and the level of completeness, independence, and extended duration of the whole service system. Completeness refers to the quality of life the system delivers in terms of supplying the resources people need while developing and maintaining infrastructure and while creating and implementing economic, health, and education systems and systems of governance. The level of independence of a whole service is assessed based on the extent to which it does not require the support of external service systems. The level of extended duration of a whole service can be defined for a whole service that is supplied for only a short period of time or one that is provided indefinitely (e.g., whole services such as smart cities). In the framework of the holistic service system, therefore, the various services supplied by a provider must also be interconnected. Moreover, customers must cocreate the value while perpetuating the service atmosphere in a manner analogous to how ecosystem services function, thereby yielding sustainability as in the model of the sustainable city. A sustainable service network, therefore, is that which holistically considers the entire service system and not only its individual services. Likewise, a sustainable service network necessarily involves the sharing of physical and nonphysical resources, the renewal of those resources in cyclical processes, and the rebuilding of societal infrastructure.

The main characteristics of a city as a whole service or as a holistic service and the difference between the two are summarized in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 City characteristics in terms of whole service and holistic service

|

Whole |

Holistic |

Physical boundaries |

Place |

Environment |

Human boundaries |

People/individuals |

Community |

Provider |

Mainly the city |

Everyone |

Customer |

Mainly the residents |

Everyone |

Value hierarchy |

Mainly information and knowledge |

From information to wisdom |

Value dimensions |

Economic, social, and environmental values |

Sustainable values |

Value models |

Value in-exchange and value in-use |

Value in-exchange, value in-use, and value in-return |

Integration |

Unconnected services |

Connected services |

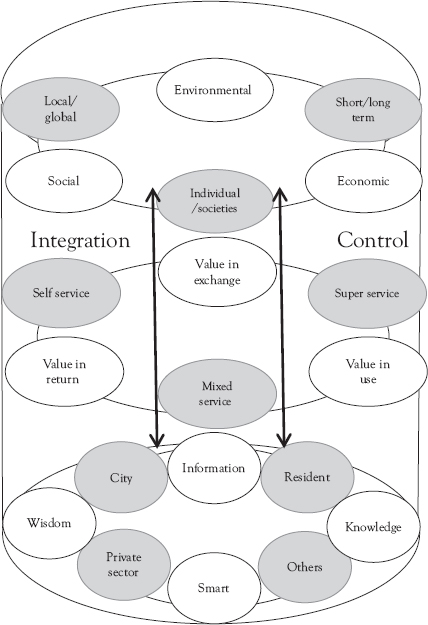

Service-City Architecture

To implement the service-city model, the design, provision, and use of each service in the city should be built and synchronized using a unique architecture (Figures 5.1 and 5.2). This architecture comprises the three horizontal layers of design (Figure 5.1a), provisioning (Figure 5.1b), and sustainability (Figure 5.1c) and the two cross-cutting, vertical layers of integration and control (Figure 5.2).

The horizontal layers of the service-city architecture are applied sequentially when implementing the service-city model. Beginning with the design layer, both provider and customer are chosen from among the four options of city, residents, private sector, or other, and the level of hierarchy is chosen from the DIKIW pyramid (Ackoff 1989; Spohrer, Piciocchi, and Bassano 2012). Progressing to the second layer, provision is decided by choosing the appropriate value provision model (e.g., inexchange, in-use, or in-return) and mode of operation (e.g., self, super, or mixed). In the last horizontal layer of sustainability, the social, environmental, and economic dimensions that are essential to the value should be defined while considering all short- and long-term and local and global effects and the influence that these will have on both individuals and societies. Finally, the three horizontal layers are integrated and controlled by the addition of supporting services such as regulations, and so on. (Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.1 Horizontal layers of service-city architecture: (a) design, (b) sustainability, and (c) provision

Figure 5.2 Vertical layers of integration and control in the service-city architecture

The service-city model should also be imbued with circularity as an integral part of its design. Indeed, the notion of circularity should be built into each horizontal and vertical layer (i.e., in the design and provision of each individual service as well as in the integration of some services). Additionally, it should be incorporated as an essential part of the framework for holistic service systems, thereby transforming the service-city model from a two-dimensional to a three-dimensional model. As such, each service will be produced and provided while considering multiplicities of providers and customers, direct and indirect, to ensure the circularity of all the service’s tangible and intangible values. This approach, in turn, facilitates the efficiency and effectiveness of each service provision as well as of the entire system. In the following chapter, some examples of the service-city are presented.