Chapter 14

Goals and Metrics

We all know that “what gets measured gets managed”—and for sustainability-related initiatives it is no different. Thus, the fourth element of the Corporate Sustainability Scorecard—in the Governance section—is goals and metrics.

The overarching strategic question that senior executives and board members should be asking is:

Key Question: How does our company set goals that drive footprint reduction and long-term value creation for the most material issues across our value chain?

Unilever (#150 on the 2017 Fortune 500 list) is well into its multiyear Sustainable Living Plan, which was launched in 2010 to “decouple” revenue growth and value creation from environmental and social impacts. This decoupling is driven by the company’s 2030 goal: to cut in half the environmental impacts/footprint associated with making and using its products as the company continues to grow its business. In 2012, Unilever CEO Paul Polman further drove the focus on long-term value creation when he stated at the World Economic Forum in Davos, “We don’t do three-month (financial) reporting anymore.”i Unilever has inspired many “smart follower” companies to grow their revenue while cutting their impacts and footprint.

To help answer this key question, the Scorecard analyzes a company’s approach to establishing and tracking performance of sustainability goals, including:

–The goal-setting process

–The time horizon for framing the sustainability goals and metrics

–The content and impact of the individual targets that are set, measured, and reported on

Within each of these buckets, executives evaluate their company performance on several KSIs. For each KSI, they rate their company performance on the scale of Stage 1 through Stage 4.

Goal-Setting Process

For many companies, the goal-setting process, as it relates to environmentally and socially related topics, is evolutionary rather than revolutionary. By that we mean today’s goals are likely grounded in a history that dates to early goals—especially around occupational safety and environmental, health, and safety (EHS) compliance.

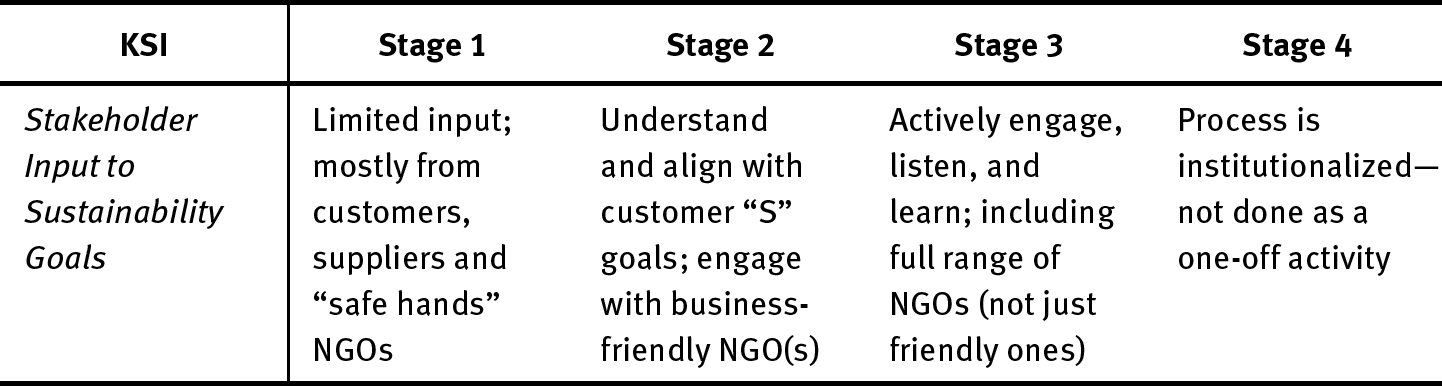

The Scorecard addresses the goal-setting process with three key sustainability indicators (KSIs): the critical starting point (materiality assessment of key ESG impacts and risks; the general company philosophy about sustainability goals; and the extent of external stakeholder input into the goal-setting process.

KSI 4.1: Materiality Assessment of Sustainability Impacts/Risks. The “right” starting point for any set of sustainability goals is what is commonly referred to as a materiality assessment.

The term materiality is a convention within the financial community relating to the importance or significance of something relative to the corporation. In financial terms, information is material if its omission or misstatement could influence the economic decision of users based on the company’s financial statements.

In the sustainability world, a materiality assessment is a comprehensive review of the key (negative) environmental and social impacts and issues associated with the company and its industry sector. Of course companies have many positive impacts, especially on the “social” side—such as offering employment, benefits, community outreach, etc. But a materiality assessment identifies major negative impacts a company has—including, for example:

–Environmental Impacts: Greenhouse gas (GHS) emissions, other air emissions, water use; water contamination; waste disposal; etc.

–Social Impacts: Lack of diversity and inclusion; adverse impacts on health and wellness; labor issues; human rights abuses in the organization and the supply chain; etc.

–Governance Impacts: Lack of active board involvement in sustainability; lack of diversity on the board of directors; etc.

As companies move from Stage 1 to Stage 2, their materiality assessment becomes more formal, addressing impacts not only in the company’s own operations but also throughout its value chain.

As companies advance to Stage 3 and beyond, they reach out to various key stakeholder groups to solicit input on identifying material issues—and then ultimately address those issues. Key stakeholders with a strong interest in these issues certainly include not for profit environmental groups or socially related groups—typically referred to as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Several examples of companies in Stage 3 or beyond include:

–Chipotle Mexican Grill: Conducted a formal materiality assessment in 2015–2016; a major issue for the restaurants was waste management. The company set a goal to divert 50 percent of its restaurant waste from landfills by 2020, and achieved a 40 percent diversion rate in 2017.

–Nestlé Waters: The North American company committed to certifying 100 percent of its sites to the Alliance for Water Stewardship Standard by 2025.ii

–Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken: The Swedish company works with stakeholders as they plan to create and sustain value on a three to five-year basis.iii

In each of these examples, the company set a major long-term goal directly aligned with one of its most material ESG issues.

KSI 4.2: Philosophy Regarding Sustainability Goals. For most companies, publicly stated goals tend to receive considerable external scrutiny. As a result, two things typically happen. First, the draft goals and metrics undergo extensive internal review before they are made public. Second, partly because of that internal review, the public goals are often conservative. CEOs and senior executives like to meet their goals; thus, it is only reasonable that—at least early in their sustainability journey—the goals have a high likelihood of being achieved. That situation defines Stage 1 goals.

As companies move beyond Stage 1, the most important factor is ensuring that their primary public sustainability goals address the company’s most material environmental, social, and governance (ESG) impacts. For a further discussion of materiality, see Chapter 7—Environmental Stewardship: The “E” in ESG.

Companies that move to the leadership level (Stage 3 and beyond) have goals that are very aggressive in reducing their most material risks and impacts throughout the value chain. They also have goals that focus on growth—namely goals that embed sustainable thinking into research and development, and that drive sales of more sustainable products, services, and solutions. A few examples:

–Anheuser-Busch InBev: The global beverage company launched 2025 goals tied to its most material issues: reducing CO2 emissions by 25 percent; sourcing 100 percent of electricity from renewables; using circular packaging for all products; improving water availability and quality in all communities in high stress areas and improving the livelihoods of its direct farmers.iv

–Walmart: Project Gigaton was launched to cut GHG emissions across the company’s global supply chain by one gigaton (one billion tons) from 2015 levels by 2030.v

–Xerox: An early leader, the company’s focus since the 1990s has been to produce “waste-free products from waste-free factories.”vi

In each of these examples, the company took a bold step that garnered the support of NGOs. In the case of Vodafone, the effort was done in direct collaboration with NGOs.

KSI 4.3: Stakeholder Input to Sustainability Goals. Let’s face it: the process of setting goals at companies is inherently internally focused. Sure, the starting point is to benchmark competitors and peer companies—to make sure your company goals are aligned or stronger. But the nuts and bolts of setting goals is internal.

In setting sustainability goals, leading companies have reached outside their companies to solicit input from external stakeholders, thought leaders and advisors in various ways.

–Dell: The company worked with NGOs to set carbon reduction goals; committed to reduce GHG emissions 20% by 2020.vii

–Vodafone: The company committed to sourcing 100 percent renewable electricity across its operations by 2025, as part of The Climate Group and CDP-led RE100 initiative.viii Twenty-five of the RE100 member companies had reached 100 percent renewable electricity by the end of 2016.

In each of these examples, companies clearly viewed the benefits of NGO input to their goals outweighing the risks of perhaps inviting unrealistic or very difficult to achieve goals.

Time Horizon of Sustainability Goals

Most environmental and social issues are complex, diffuse, and more regional, national, or global in nature than they are short-term and local. As a result, the time horizon for sustainability goals typically involves looking out at least three to five years. For larger companies with global operations and for any company with a global supply chain and global customer base, the time frame can be even longer.

The nature of your industry sector certainly has an impact on the time horizon as well. For service providers and information technology companies, two to three years is a very long horizon. At the other extreme, electric utilities, oil and gas companies, chemical companies often make capital investments that are on the books for thirty to fifty years or longer.

The Scorecard addresses time horizon of goals with two key sustainability indicators: one dealing with the typical horizon for long-term goals for most companies; and a second that looks at what a growing number of companies state in terms of what we call “ultimate” sustainability goals.

KSI 4.4: Long-Term (5–15 Year) Sustainability Goals. The clear majority of public companies today—especially large ones—have a set of sustainability-related goals. In many cases, these current goals have their roots in earlier environment, health, and safety goals that may have existed for decades. Common EHS goals deal with safety, compliance, etc.

Today, the range of company activity on long-term sustainability goals is given below.

Some examples of robust sustainability goals follow:

–AT&T: The telecommunications leader set a goal to enable carbon savings 10x the footprint of its operations by 2025.ix

–Campbell Soup: The iconic company announced its 2020 Destination Goals for CSR and Sustainability in 2011. The goals include efforts to improve the health of young people and reduce the environmental footprint of its products.x

–Ingersoll Rand: Committed to a 35% reduction in GHS footprint by 2020.xi

–Marks & Spencer: The UK retailer launched Plan A in 2007 as the company’s way to help build a sustainable future, enabling its customers to have a positive impact on wellbeing, communities and the planet. The first phase of Plan A had 100 new social and environmental commitments. The second phase launched in 2010 had 80 new commitments and a goal to become the world’s most sustainable major retailer. The company is now in the third phase, called Plan A 2020. xii

–Nestlé: The Swiss-based multinational announced target year 2020 commitments in support of UN SDGs in March 2017xiii and plans for all its 150 European factories to be zero waste by 2020.xiv

–Sainsbury: The UK retailer launched its “20 by 20 Sustainability Plan” in 2011, setting out twenty sustainability targets to be achieved by 2020.xv

In each of these examples, the goals are public commitments—often quite bold ones— that drive the company to make significant performance improvements.

KSI 4.5: Ultimate (e.g., 2050) Sustainability Goals. Over the past decade or so, a small but growing number of companies have made bold statements about the sustainability ambition they ultimately aimed to achieve—without naming a specific target year. One example is noted just above: Marks & Spencer’s goal to become the world’s most sustainable major retailer.

Today, the range of company activity related to these ultimate sustainability goals is given below.

Below are some of the impressive sets of goals around essentially zero negative impacts—either in total or in a key material issue such as carbon or water.

–AkzoNobel: The Dutch coatings company committed to accelerating its sustainability agenda by announcing in 2017 a new ambition to use 100% renewable energy and become carbon neutral by 2050.xvi

–Coca-Cola: The company met its 2020 water replenishment goal by the end of 2015. The 2020 goal involved safely returning to communities and nature an amount of water equal to what the company uses in its finished beverages.xvii

–DHL: The German package delivery company committed to zero emissions logistics (meaning zero net GHG emissions in its own operations and its transportation contractors) by 2050. This goal was DHL’s contribution to achieving the goal of limiting global warming to well below 2° Celsius established at the 2015 Paris climate conference (COP 21).xviii

–Interface: The carpet manufacturer embarked on what the company called a “mid-course correction” in 1994 and later launched Mission Zero with a goal to eliminate any negative environmental impact by 2020.xix

–Kingfisher: The international home improvement company based in the UK set a clear direction: “Net positive is our sustainability ambition. It means innovating in our products and services to enable our customers to have more sustainable homes; transforming our business to have a restorative impact on the environment; and making a positive contribution to society and the communities in which we operate.”xx

–Nestlé: stated its overall ambition to strive for zero environmental impact in our operations. “We have set clear commitments and objectives to use sustainably managed and renewable resources, operate more efficiently, achieve zero waste for disposal and improve water management. We also continue to actively participate in initiatives that reduce food loss and waste, and that preserve our forests, oceans and biodiversity.”xxi

–Sony (Japan): Has a goal of “zero impact” by 2050; its plan is outlined in its “Road to Zero” Initiative.xxii

–Walmart: The CEO set three long-term, aspirational goals in 2005: to operate with 100 percent renewable energy; to create zero waste; and to sell products that sustain resources and the environment.xxiii While these aspirational goals did not have a specific deadline, Walmart subsequently set more specific goals and metrics, including a set of 2025 goals.

In each of these examples, these leading companies go beyond setting the more typical five-to ten-year “long-term” sustainability goals (discussed above in KSI 4.4) and also set a “net positive” or similar ambition.

Content and Impact of Sustainability Goals

The first two sub-elements of goals and metrics that we discussed assess a company’s status on the goal-setting process and the time horizon of sustainability goals. This third (sub-element) focuses on results.

The results of sustainability goals normally fall into one of two buckets:

–Reducing Cost and Risk—All the actions and initiatives companies take to minimize their impacts in their own operations and throughout their supply chain to reduce cost and/or risk.

–Growing Revenue, Options for Future Growth and Brand—The investments in research, product development, and customer relationships that result in a suite of company offerings (products, services, solutions) that collectively have a lighter footprint and help the customer achieve its sustainability goals.

The two KSIs in this section address those two sides of the coin and assess the extent to which the company’s accounting systems are set up for tracking them.

KSI 4.6: Magnitude of Reduction in Company Footprint or Impact. In characterizing a company’s sustainability goals, it is important to consider not only the content and degree of “stretch” in the individual goals—but also the track record of accomplishment. Over time, incremental improvements in footprint reductions are tougher to achieve, like improvements in a company’s safety performance.

The rating criteria in the Scorecard are shown in the table below.

–3M: The company’s Pollution Prevention Pays (3P) program celebrated its fortieth anniversary in 2015. The program has prevented more than 2.0 million tons of pollutants and saved nearly $1.9 billion.xxiv

–Hasbro: The toy company achieved 100 percent renewable energy and carbon neutrality across its owned and operated U.S. operations in 2015 and 2016 (the most recent years reported).xxv

–Nike: In a bold move, the company committed to eliminate hazardous chemical discharge from its supply chain by 2020.xxvi

In each of these examples, the company has made, and continues to make, very significant reductions in its footprint, while supporting positive contribution to the company operations and financial performance.

KSI 4.7: Tracking Revenue from Sustainable Products, Services, and Solutions. The Conference Board has done an excellent job of conducting research on companies that are pursuing revenue growth from “green” or “healthy” or “sustainability” products, services, and solutions.

The following examples are all from publicly reported data by the individual companies:

–BASF: Accelerator Solutions (the company’s green portfolio) accounted for 27 percent of BASF’s relevant sales in 2017, or about €15.5 billion.

–DSM: The company’s ECO+ solutions accounted for 57 percent of the company’s total sales in 2015. ECO+ sales have an average annual growth rate of about 10 percent, and across several of DSM’s businesses, ECO+ sales have higher margins than do non-ECO+ sales. Today, ECO+ and People+ are combined into the “Brighter Living Solutions” portfolio, which in 2017 accounted for 62 percent of total sales.

–Johnson & Johnson: The company’s Earthwards® portfolio of sustainable products grew from nine products in 2009 to one hundred products in 2017. This portfolio represented over $11 billion in revenue and about 15 percent of the company’s 2017 revenue.

–Kimberly-Clark: The company’s ecoLOGICAL portfolio accounted for 52 percent of the company’s revenue in 2014 (up from 10 percent in 2010), or more than $10 billion.

–Philips: The company’s “green products” accounted for 64 percent of the company’s overall revenue in 2016.

–Siemens: The German company’s Environmental Portfolio grew to €39 billion, 47% of 2017 revenue.

–Toshiba: Sales of “Excellent Environmentally Conscious Products” rose from $3.6 billion in 2011 to $24 billion in 2015 (accounting for 42 percent of 2015 revenue).

The examples above are impressive; however, I do not want to leave the impression that this is always the case. As mentioned in Chapter 9 (The New Regulators), the picture for green investments is not all rosy. Over the years there have been many bankruptcies in the solar and renewable energy sectors.

In each of these examples, the companies decided that it was useful to define a specific portfolio of its products and services as being especially “green” or “healthy” or “sustainable.” And, in tracking revenue growth of these portfolios, the companies find that it pays to go down this path.

KSI 4.8: Accounting for Most Material Externalities (e.g., Cost of Carbon). Externalities are defined as the cost or benefit that affects a party that did not choose to incur that cost or benefit. For example, manufacturing activities that cause air pollution or carbon emissions may impose health, cleanup, or other costs on society.

This KSI aims to assess the bridge between impact reduction initiatives many companies take (e.g., waste reduction; energy conservation; reducing risk of major incidents; etc.)—and the accounting systems that run the company’s financial metrics.

Financial systems for pricing raw materials such as water or placing a cost on discharges such as GHG—are not aligned with resource availability. Here are some key examples:

–Cape Town, South Africa residents are awaiting “Day Zero”—the day when the city will shut off its taps and faucets will stay off until it rains.

–Cape Town is not the only city facing water shortages; Bangalore, Beijing, Cairo, Jakarta, Moscow, Istanbul, Los Angeles, London, Mexico City, Miami, São Paulo and Tokyo all face water shortages.xxvii

–In the United States, residents pay ten times more for water in in Flint, Michigan (located 40 miles from the Great Lakes than they do in arid Phoenix, Arizona.xxviii

The pricing of water is highly inconsistent across regions, and the same is certainly true of carbon. However, in the case of carbon, companies have been taking a leading role in assigning a cost associated with it for many years.

Over the past several years, a number of leading companies globally have been working to measure the total (financial, environmental and societal) impacts of the company. In a 2018 research report, Thomas Singer of The Conference Board provides an overview of current practices in this emerging area of total impact valuation.xxix

The range of ways companies measure their total impacts and account for carbon, water, and other material externalities is as follows:

The following examples are from The Conference Board’s report titled “Total Impact Valuation” referenced above:

–AkzoNobel: In its 3D P&L, the company shows its calculated economic, environmental, and social impacts across its full value chain.

–BASF: The company’s Value-to-Society model shows its economic, environmental, and social impacts for the external supply chain (direct and indirect suppliers), own operations, and customer industries.

–LafargeHolcim: The company’s 2016 Integrated Profit & Loss (IP&L) statement shows the results of its total impact calculation. The IP&L is divided into financial, socio-economic, and environmental categories.

In 2017, almost 1,400 companies were factoring an internal carbon price into their business plans, representing an eight-fold leap over four years. Despite this impressive increase, the number of companies using carbon pricing remains a very small fraction of all companies globally.

By making this commitment, companies are agreeing to align with the UN Global Compact’s Business Leadership Criteria on Carbon Pricing:

–Set an internal carbon price high enough to materially affect investment decisions to drive down GHG emissions

–Publicly advocate the importance of carbon pricing through policy mechanisms that consider country specific economies and policy contexts

–Communicate on progress over time on the two criteria above in public corporate reports

As of 2017, 607 companies had set an internal price on carbon, principally as a risk management tool. Of that number, 255 were companies based in Europe; 136 were based in the United States.xxx

How Do Companies Stack Up?

Starting in 2018, we are capturing data from a group of founding participants—invited to use the Scorecard for a company self-assessment and to provide feedback. As we assess the data from the first 60 companies (all Fortune 500 or equivalent), several key messages stand out:

–A significant majority of companies base their sustainability goals on a detailed materiality assessment of key ESG impacts.

–Most companies do, in fact, have long-term sustainability goals (typically looking out five to ten years or a bit longer).

–Fewer than a third (30 percent) of companies have goals around growing revenue from sustainable products (however defined).

–Only 16 percent of the companies claim they are accounting for their most material externalities—such as carbon emissions, pollution, etc. The most common example of accounting for externalities is assigning a cost to carbon, as a growing number of companies currently do (see Figure 14.1).

Thus, like with the past several elements of governance, we see that this is a good news–bad news story. The positive story is that many companies have robust longterm goals based at least in part on a materiality assessment. The bad news is that there is a very long way to go—and companies may not be focused on the most impactful ESG issues.

For example, look at the data from sixty companies on the extent to which companies account for their most material externalities.

As we approach the year 2020, many companies are in the midst of setting the next range of sustainability goals and metrics. This is because the most common time frame for these goals has been five years—and many companies have been working toward their 2020 goals, which were set earlier around 2015.

i “Corporate sustainability: Unilever CEO Paul Polman on ending the ‘three month rat race,’” Reuters, October 2012.

ii https://www.nestle.com/media/news/nestle-waters-sites-certification-alliance-for-waterstewardship-by-2025

iii https://sebgroup.com/about-seb/sustainability/our-approach-and-ambitions/our-material-issues

iv http://www.ab-inbev.com/content/dam/universaltemplate/ab-inbev/News/press-releases/public/2018/03/20180321_EN.pdf

v https://news.walmart.com/2018/03/29/walmart-commits-to-reduce-emissions-by-50-millionmetric-tons-in-china

vi https://www.xerox.com/corporate-citizenship/2011/sustainability/waste-prevention.html

vii http://www.dell.com/learn/us/en/uscorp1/corp-comm/cr-earth-emissions?c=us&l=en&s=corp&cs=uscorp1

viii https://www.theclimategroup.org/news/vodafone-becomes-latest-business-join-re100

ix http://about.att.com/content/csr/home/blog/2015/11/at_t_commits_to_goal.html

x https://www.campbellsoupcompany.com/newsroom/press-releases/campbell-reports-progresson-2020-sustainability-and-citizenship-goals/

xi https://company.ingersollrand.com/strengths/sustainability/our-climate-commitment.html

xii https://corporate.marksandspencer.com/blog/plan-a-2020

xiii https://www.nestle.com/media/news/nestle-csv-creating-shared-value-summary-report-2016

xiv https://www.environmentalleader.com/2013/10/nestle-makes-zero-waste-pledge-for-all-europe-factories/

xv https://www.2degreesnetwork.com/groups/2degrees-community/resources/sainsburys-20-by-20-sustainability-plan_2/

xvi https://www.akzonobel.com/for-media/media-releases-and-features/akzonobel-be-carbon-neutral-and-use-100-renewable-energy-2050

xvii http://www.coca-colacompany.com/press-center/press-releases/coca-cola-on-track-to-meet100-water-replenishment-goal

xviii http://www.dhl.com/en/press/releases/releases_2017/all/dpdhl_commits_to_zero_emissions_logistics_by_2050.html

xix http://www.interface.com/US/en-US/about/mission/Our-Mission

xx https://www.kingfisher.com/sustainability/index.asp?pageid=173

xxi https://www.nestle.com/csv/impact

xxii https://www.greenbiz.com/news/2010/04/08/Sony-Targets-Zero-Environmental-Footprint-2050

xxiii https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_greening_of_wal_mart

xxiv https://www.3m.com/3M/en_US/sustainability-us/goals-progress/

xxv http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/HAS/5793441862x0x966251/5A6E4060-BF62-4B21-80CB-B2008E43C01C/Hasbro_Celebrates_5th_Anniversary_of_Global_CSR_Practice_with_Release_of_CSR_Report_Playing_with_Purpose.pdf

xxvi https://www.bizjournals.com/portland/blog/sbo/2011/08/nike-to-eliminate-hazardous-chemical.html?page=all

xxvii https://www.bbc.com/news/world-42982959

xxviii https://www.citylab.com/equity/2016/02/why-water-costs-100-times-more-in-flint-than-in-phoenix-water-value-crisis/463152/

xxix Thomas Singer, “Total Impact Valuation: Overview of Current Practices,” The Conference Board, 2018.

xxx http://b8f65cb373b1b7b15feb-c70d8ead6ced550b4d987d7c03fcdd1d.r81.cf3.rackcdn.com/cms/reports/documents/000/002/738/original/Putting-a-price-on-carbon-CDP-Report-2017.pdf?1508947761