CHAPTER 6 The Six Principles of Behaviour

Principle 1: People Need to be Able to Predict their Environments

Most of the time we are in environments that are relatively familiar, and at such times we are not aware of how we are scanning the environment and testing it against our expectations. We often only become aware of this process when there is an exception or surprise. We can underestimate how important it is to predict and monitor precisely because we are not fully conscious of doing so. Indeed, if we were fully conscious of the process all the time, we could not easily concentrate on the task at hand. Whenever we see or experience an unusual event or failure of prediction, we cannot ignore it. We cannot simply note an exception; we must explain it, so that we do not get surprised again.

For example, a colleague who is usually friendly and courteous cuts us short. Why? We must have an explanation and if we can’t find one we will invent one. We are very inventive. So our colleague may be (a) very busy, (b) upset, (c) angry at a work related task or (d) some other reason. Most people are primarily concerned to discover ‘is it anything I have said or done?’ We need to know what reactions we provoke by our own behaviour or the world becomes an unpredictable and potentially threatening place. Some explanations may mean that we do not have to change our predictive model: ‘His mother has recently died.’ Others may imply that we do: ‘He is fed up with you constantly asking how he is.’

From virtually the moment we are born, we embark on the quest of observing and classifying behaviour so that we may understand it and learn how to predict it. This heuristic process helps us figure out from our earliest experience what makes someone come to feed us, what makes someone laugh, what makes someone angry. We learn to predict what encourages generosity, what encourages love, what causes indifference, what leads to friendship, what to bullying and so on. We learn from our immediate family and friends, then from school, the community, the media and the organisations in which we work.

We do not have to be taught to do this. It is an essential, natural, human process. This heuristic methodology results in a set of models and rules for predicting behaviour of people and the physical world around us. In doing so we are all developing our own theory of human behaviour as well as a theory of the material world. It is not only important to us; it is essential to our sense of well-being and even survival. In certain circumstances, if we ‘read’ the situation wrongly, it may put us in serious danger.

Think for a moment about what makes you nervous or anxious. It is most often caused when you are about to go into a situation where prediction is difficult, but the outcome is critical. For example, many people become anxious before having a job interview, a final exam, a public presentation, a negotiation or, at the extreme, combat. What eases that anxiety is the reassurance of preparation – the work of anticipating and rehearsing the what-ifs. What if I am asked this? What if she gets angry? What if they find the presentation boring? (These are Critical Issues: see Chapter 15 Teams and Teamwork.)

If we are to avoid constant stress and are to feel comfortable, we must be in an environment where, in general terms, the situation and people’s behaviour are predictable. Now, of course, this does not mean we need or want to predict exactly what someone is about to do or say.

Nonetheless, to avoid anxiety we do want people to behave in a way that stays within predictable boundaries. This means we can operate in a stable environment and consequently focus our attention on what we have to do – operate the machine, discuss a business deal, write a report.

When one of the authors, Ian Macdonald, first started working in a large psychiatric hospital in 1975, he made his first visit to a locked ward. On entering, some of the residents immediately rushed up to him. One put his face a few centimetres from his; another touched his arm; another circled him, staring. In ordinary life such behaviour would have been extremely threatening. It is not benign for strangers to behave in such a way unless there is a threat or intention of sex or violence, or both. Macdonald very quickly had to learn a different set of predictive rules, to ascertain in this context what was a real threat and what was simply a different normality.

In a less dramatic way we all have to learn these new rules or norms when we visit countries overseas, move to a different community, move to a new organisation or simply visit someone’s home for the first time. Most people can remember instances from childhood when such visits led to surprises. This family does/does not eat together. They argue a lot. They don’t talk to each other. They let/don’t let their children watch certain TV programmes. They do or don’t allow mobile phones or limit ‘screen-time’ for children. They do/do not take off their shoes in the living room. We learn not to blurt out our surprise, but to observe, learn and increase the scope of our predictive models. Some we find can be comfortably accommodated, others not so.

Similarly, think about visiting or starting work in a new company. Induction is not simply about work and safety processes. You must learn how to address people. Do you use first names? Where do you find facilities, for example, the canteen or toilets? What is a reasonable break time? And so on. It is at times like this our heuristic process becomes more conscious and so we are more aware of the process we have used and continue to use all our lives.

It is important to state here that predictability gives a sense of stability and reassurance even if the situation appears to be counter-productive. Again, Ian Macdonald has worked with families that may be described as dysfunctional but are in another sense stable. Children learn to see the patterns of behaviour and avoid at least the worst excesses. They learn what triggers violence, how differently an adult behaves when drunk or drug affected. These may be very unhappy relationships, but they endure because the participants have learned the dance of survival by predicting behaviour.

If we look at industry, certain companies are characterised by dreadful workplace relations, but they are predictable. The workers know the management are bastards and out to get them. The management knows the workers are lazy, out for what they can take with the least amount of work. Each side plays its predictable role, keeps to the script and enters a regular ritual of protracted, tough negotiations trying to win points from each other. It may be economically wasteful, even disastrous, but it is predictable. Everyone knows their place and hangs on to their correct view of the world. We all know where we stand. Historically in many societies, class and caste systems may bestow privilege on some and oppress others. However they may be stable due to their predictability at least until the excesses become unbearable.

Thus predictability is critical. One extreme public example of this happened on 11 September 2001 (aka ‘9/11’). Worldwide, many people had that date imprinted in their minds forever. The loss of life was appalling. However, the deeper shock was the unpredictability of the event. Worse, unlike an earthquake, it was a deliberate, indeed meticulously planned, human act that was not foreseen.

In the media interviews, people used revealing comments. It was not a normal hijacking. Now hijackings are not normal in one sense, but we had come to expect that hijackers don’t want to die. They make demands: they threaten; they do not deliberately fly planeloads of innocent people into buildings. Why? For what purpose? What on earth had we done to deserve this? What sort of people are the hijackers?

Enormous amounts of energy have necessarily been expended trying to answer these questions. Until we can answer them, we cannot feel safe. When we board a plane or work in a skyscraper, we cannot help wondering and considering what we would do if … What could we do? Why do some people hate us? Why do some love us? It is intolerable to leave these questions unanswered, or we would live in a random universe, a world of uncertainty where we have little or no sense of influencing our own destiny.

Now, sadly we are much more familiar with suicide bombings and they no longer produce the level of shock to the outside world although their victims are no less damaged or killed.

So we must learn to predict, to have an effective model that does not result in constant surprises, especially shocks. People who have great difficulty heuristically constructing such models, for example, people with autism, suffer great anxiety and express a great need for control. In short, we must understand social processes in such a way that we can generally predict behaviour around us.

We must also understand the difference between prediction of a population’s behaviour and the prediction of an individual’s behaviour.

Understanding social processes involves not just explaining why someone behaved as they did but also predicting likely behaviour. However, it is important to distinguish between predicting behaviour in general and predicting an individual response. For example, if a person is working and producing an output, it is a general principle to say that, if that person receives valid feedback and due recognition, he or she is more likely to continue to work hard, giving care and attention to the quality and quantity of what is produced compared with someone who receives little or no feedback or recognition. This will not, however, be true in every single case. Some individuals will work hard despite poor leadership. Others will find it difficult to work hard even with good leadership. Thus, we can work from general principles about people in general but we need to consider the individual case and exceptions, bearing in mind that an exception does not necessarily invalidate the principle. If we confuse the general and the particular we can make some serious mistakes. For example, a person who smokes may well cite an elderly relative ‘who smoked all their life and never got cancer’ as a means of denying the dangers of smoking. In effect, this technique is a way of avoiding dissonance.

It is impossible to predict in minute detail any individual’s behaviour (including our own). This does not, however, differentiate natural science from social science. No theory can predict exactly the behaviour of a single entity, be it a person or atomic particle. Paradoxically we can make a general prediction (in social science) that people will actually resist prediction if it is felt to be manipulation. People in general do not like to be labelled, categorised or put in boxes because it appears to deny our unique individuality. We need to be very aware that a general prediction will not account for every person’s behaviour. We are unique but we also know that we are extraordinarily similar in terms of biological makeup and our need for food, shelter and companionship. We respond similarly to perceived threat, cold, lack of sleep and lack of food. In our everyday lives we depend on the general predictability of behaviour of those around us in the street, on trains and in our workplace or home, but we resist the notion that therefore we are totally predictable as individuals.

Whilst there are always differences, there are also common characteristics. The problem with using statistical models and probability statements lies with the reality that probabilities are about populations while personal experience is by definition singular. Therefore, whereas it may be both true and accurate to predict that a company will reduce the workforce by 10% over the next year, at the end of the workforce reduction employees do not experience a 90% role. Either I keep my job or I do not, zero or one. When we look at safety statistics by plane, train or car, we may know the statistical safety figures. However, for each of us we either have an accident or we don’t, again zero or one. Many of us choose to behave unsafely at work because ‘we will get away with it’, gambling on the zero not the one. Thus, experientially, we are not overly impressed or influenced by statistical evidence even when it is true because the basic gamble for the individual is win or lose. Even when we lose, we may fool ourselves that we nearly won because our raffle ticket was the number above or below the winning ticket.

Leaders seeking to influence behaviour will not be very successful if their main or only argument is quoting statistics. The examples must be taken through to personal experience, so that the person links the statement to personal experience. We do not particularly like to be normal, average, or accept the implication that we are effectively indistinguishable from others. This lack of recognition of individual difference reduces us to apparent objects. In understanding the detail of social process we must work from general principles about people to specific hypotheses about particular groups or cultures and then to individual need. It is important to work at all three levels at once and not exclusively at any one or two. That is, we must move carefully from the general to the particular, shaping our explanation and behaviour as we do. For example, at work I may start with a general assumption that people require feedback and recognition. I, then, may make a specific statement about a particular group, say a crew of underground miners, a team of young Aboriginal Australians, a troupe of actors in a theatre company. This will involve how that recognition and feedback is most appropriately given. In our experience it is not helpful to publicly single out miners or Aboriginal people. Better to give such recognition quietly and with little fanfare. An actor, however, may require public individual praise, applause and so on. One final important step, however, is to take into account individual differences. Not all miners, indigenous Australians or actors are the same (see Box 6.1).

We are very keen on exceptions, because it appeals to our individuality and a sense that we are not victims of predetermined fate. There are huge industries that exploit our need to do this: smoking, drinking and gambling. The gambling industry and particularly lotteries are dependent upon our belief that we might beat the odds. Some of the most dangerous behaviour at work and socially is founded on the notion that it won’t happen to me, exactly the opposite of the gambler who hopes, against the odds, it could be me. Thus we have the contradictory, but absolutely human, behaviour of running across a busy street to buy a lottery ticket.

Box 6.1 Individuals – Statistics

In a mining company in Australia the leadership were about to offer staff conditions including a salary structure to supervisors who were at the time on hourly rates of pay with overtime. As part of the consideration an analysis was done to see what percentage of supervisors’ pay was due to overtime. The overall figure came out as just over 15%. Therefore it seemed logical to think about buying out the overtime by adding a figure around 15% to the salary.

On closer analysis, however, a very small proportion of supervisors covered a significant amount of overtime (some up to 40% of base pay). Further, we found that those supervisors who earned these large amounts were disliked by their crews and fellow supervisors. Their crews saw them as dishonest, since they fixed the system so that they came in on weekends, outside the normal shift, for the slightest of reasons. They also saw this as unfair. Very few were even moderately trusted. Taking this small group out of the equation reduced the overtime loading to below 10%. Therefore, the leadership built in a loading to the salary of 10%, paid to all supervisors irrespective of time worked, which was seen as fair and honest by the productive supervisors and highly punitive by the poor supervisors, most of whom left. Thus, by using an analysis at all three levels – general, group and individual, the organisation retained effective workers; lost people who were exploiting it and reduced cost from the first analysis. This example also works if it is seen as using the trio of leadership tools: systems, symbols and behaviour: the systems being the employment and overtime systems, the behaviour being the leadership’s efforts to carry out a detailed analysis (perceived as fair and honest) and the symbolism of rewarding effective supervisors and not rewarding poor performers.

Building general, predictive models with attached statistical probabilities is not demeaning to individuals. We do it throughout our lives. However, a leader must not impose this model on either a specific group of people or an individual since it objectifies the person. Instead, it is a starting point to be able to identify groups and, within groups, specific individuals.

Nevertheless, it is not simply a matter of having predictive models. We also imbue these models with value and morality. They are infused with a sense of right and wrong, good or bad, and all the shades of grey in between.

This brings us to the next principle.

Principle 2: People are not Machines

This common sense statement that people are not machines is central to understanding change processes. It is one that, despite its appearing obvious, is easily forgotten.

Change processes are often described as organisational change, culture change, re-engineering. We look for efficiency improvement, performance enhancement and productivity gains. What all of these have in common is that people have to change their behaviour in order to achieve them. Without behavioural change there can be no improvement. Thus all change processes, whether technically or commercially driven, depend upon people doing things differently. Therefore any discussion of organisational change needs to address how behaviour is influenced. Anyone who wants to bring about behaviour change needs to consider their assumptions about behaviour and how and why it changes.

This does not mean that everyone, or even those leading an organisation, has to be a professional psychologist. These chapters explore the core principles about behaviour that have significant impact on the success or otherwise of any social process.

Many change processes are initially driven by technological change, the availability of equipment, resources and materials that can potentially lead to improvement in effectiveness and efficiency. This should not obscure the essential social process (see Box 6.3).

PERSON–OBJECT

In the relationship shown in Figure 6.1, we do not have to worry about the object’s will or intent. What matters is the person’s will. The object will react to any action on it in a predictable way, according to the laws of physics. Thus if I throw a cup on the floor and it breaks, it will break according to the force applied to it, the hardness of the floor, the angle that it hits the floor, and so on, and will depend on what the cup is made of. In this process I do not have to worry about what the cup thinks about being thrown to the floor. It will not try to break neither will it try not to break. It will not consider my intent as cruel or unjustified or reasonable. Neither does it have any notion of its own value or the value I attribute to it. Thus I can experiment quite freely on physical objects and entities.

PERSON–PERSON

Look at Figure 6.2. You can see that when it comes to my action on people there are (at least) two wills operating. If I try to throw a person on the floor, he or she will certainly have a view about it. The context as well as intent will influence behaviour. For example, is the person a wrestling partner or a complete stranger? A person will presumably try not to break; will try to make sense of my behaviour. Why did I do that? Was it accidental? Was it typical? If I announce my intent that will also influence the event, unlike the relationship with the cup, which will behave no differently whatever warning I give it. Further, this event will not end at impact. The person will try to make sense of what happened after the event, which in turn will influence future relationships. Any person will have a sense of both their own personal value and a judgement about how I value them.

Box 6.2 Different Types of Relationships

In our relationship with the world there are basically two fundamentally different types of relationship. The first is our relationship with other people; the second is our relationship with objects.

For an in-depth analysis and discussion of these relationships and their differences, see D.J. Isaac and B.M. O’Connor, ‘A Discontinuity Theory of Psychological Development’ in Levels of Abstraction in Logic and Human Action (1978), ed. E. Jaques, Heinemann educational books.

The distinction between people and object relations may seem very simple and obvious. However, despite this simplicity we all sometimes muddle them up. The authors have heard leaders describe people as units (of labour) or numbers. In one organisation workers had their employment number instead of their names on their overalls. We hear about cost reduction and efficiency improvement, meaning that people will lose their employment. The phrases used to describe change often do not mention people specifically, for example, cultural change. We have all heard discussions that assume that people have no will or that their will is a nuisance. It can easily be experienced as hypocritical when the leadership extols vision and mission statements about the apparent value of people, customers and being the chosen supplier, employer when at the same time people are being treated as objects. Planning the change process can reduce people to statistical events. Treating people in this way may not even be deliberate but it has the effect of objectification. It can be comforting for the leadership to assume the people–object relationship because it gives the illusion that people can be controlled. We can control objects; we can only influence people. Treating people as objects breeds cynicism and malicious compliance. It is always worthwhile to examine if and how in high-level discussions, the current language used and the systems reduce people to objects. In our view, one of the worst examples but one that is very common is the phrase human capital.

Of course we can also get confused the other way round. We sometimes behave towards objects as if they did have will and intent. We plead with a car to start, curse a computer for crashing. We try to persuade machines to keep going, encourage them to work faster or stop. What do we think we are doing at such times? We have projected the qualities of people (at least will) onto the object. If we can do this, we have a chance of persuading the printer to work. Every now and then such persuasion coincides with a restart of the machine. This only encourages us to continue with the illusion that objects are temperamental and have human qualities.

While it may be amusing to reflect on our own or others’ attempts to persuade objects to act reasonably; it is less amusing to reflect on people being treated as objects. In extreme form this constitutes oppression and abuse. The irony is that attempts to control people completely are essentially self-defeating. Not only is there a question of morality but the energy required to maintain such a controlling regime will not, over time, produce an efficient outcome since by definition it stifles initiative, creativity and enthusiasm. The energy put into control will exceed the energy produced from the ‘controlled’ person or group (this occurred, for example, in pre-1989 Eastern European economies). Confusion between people and objects often occurs without deliberate intent, for example, when introducing a new IT business-wide system, or during technological production process improvement. The discussion often focuses on the benefits of the new ‘objects’ while the role of people who must implement, run and improve these systems are effectively ignored or discounted. The case for the change may be judged to be obvious, in terms of rational, economic argument, so we expect people to comply. If people based all their behaviour on purely objective logic why would anyone smoke, not wear safety equipment or drive too fast?

Box 6.3 Consider Relationships

Thus, if we are serious in accepting that people are not machines then each relationship needs to be considered in the following terms:

• What is the other person’s view of an event?

• How does the other person view you?

• Can you predict accurately how the other person is likely to react now and over time?

Certainly many projects are started, or relationships entered into, without due consideration of people’s views or without articulating the hypothesised answers to the three questions below.

If we really can be disciplined about not treating people as machines or objects, then we can try to understand how people view the world. We need to understand not only what ‘the organisation’ needs, but also what people need and what they assess as worthy or unworthy. Only then can we be really effective in introducing change and begin building a positive organisation (see Box 6.3).

Next we will examine and define what we mean by values and culture. Values and culture are both terms that are used widely but often with different meanings. We find such terms are often vague and only give the illusion of meaning. We define culture very specifically. We also make a central proposition which is contentious: that all people share the same values. This counter-intuitive notion actually forms the basis for understanding productive social cohesion and is perhaps the most radical proposition in the book. In short we argue that our behaviour and decisions are value based.

Principle 3: People’s Behaviour is Based on Six Universal Values

We have explained that we need to predict our environment, both in terms of how others behave and how others react to us. This stems from a very basic need not only for security and survival, but also for association. We are social, and our survival depends upon others. So upon whom can we depend? Who is on ‘our side’, who is friend, who is foe? Our fundamental proposition is that we answer these questions by judging, or evaluating, behaviour against a set of universal values (see Box 6.4).

Part of the problem with the word value is that it can be used as an abstract or concrete noun, an adjective in terms of a quality and a verb in terms of an activity.

With the frictions that are causing so much mayhem and commentary around the globe at present, it seems that ‘values’ and their variability are at the core of every problem and conflict.

To quote from Donald’s ‘Origins of the Modern Mind’: ‘we are social animals, we have evolved as such and our brains are uniquely developed to process social signals. Our continued survival as a species is dependent upon our ability to build and maintain cohesion in our social group’ (Donald, 1991, President and Fellows of Harvard College).

This confusion of language can be seen in many settings. For example, when talking to workers and their managers about difficulties in their working relationships, we often hear, the problem is they have different values from us. When we talk to these same people in the context of their communities, churches and sports teams and ask why they can work together so constructively there, they say, ‘Here we have the same values.’ Often these are the same people. We do not believe people change their values with their work shirts. It is clear that something is different, but it cannot be their values if values are at the core of our social existence.

Box 6.4 Common Language and Definitions

Before we examine this issue of values and culture in more depth it is important to define our terms. As mentioned earlier we have to use language that is in common usage and has social meaning. We are not saying these other meanings are invalid, only that we need to be precise about what words mean in this context. Here we define and discuss the way some terms are used.

VALUE

Defined as behaviours which, when assessed positively, strengthen social group cohesion; when assessed as a negative, weaken it.

UNIVERSAL VALUES

This is a set of six ‘values’ that are essential properties of constructive social relationships that result in productive social cohesion. They are adjectives describing behaviour: loving, trustworthy, dignifying, courageous, honest, fair; or they can be abstract nouns: love, honesty, trust, respect for human dignity, courage, fairness.

HEURISTICS

Defined as a method or process of discovery from experience.

It refers to how we find out and learn from a range of experiences as to what is of positive value and what is not. It is how we generate the rules by which we can judge situations and behaviour.

MYTHOLOGY

Defined as the underlying assumption and current belief as to what is positively valued behaviour and what behaviour is negatively valued and why it is so.

These are the rules that we have learnt heuristically, for example don’t trust strangers. This statement is the tip of the iceberg; again heuristically formed. We do not trust strangers because we cannot predict their behaviour and they may hurt us. We build mythologies unconsciously and consciously from, amongst other things, tales of morality, films, lessons from family, friends; the media; observation of others. They form our belief system about how to interpret behaviour.

We call these assumptions or beliefs Mythologies because:

1. They are linked to the core values.

2. They are a mixture of mythos (stories with emotional content) and logos (rationality).

3. Mythologies, myths in common usage are stories that contain a fundamental truth, even if the facts are not true, for example, the story of Daedalus and his son Icarus: Icarus ignored his father’s warning not to fly too close to the sun or the wax holding his wings would melt and he would fall and die. Icarus ignored his father’s warning and did fall into the sea and die. Thus the fundamental truth – the need to show respect for your father and family by listening to and thinking about advice.

As people we do not operate either entirely rationally or entirely emotionally.

In our experience People use the term value in many different ways to describe very different concepts. People mix the concepts of value, heuristics, mythology and behaviour and call them all values. For example the quote, ‘People don’t value the old values anymore.’

• It is our contention that values, in terms of the universal values do not change. Neither are they a matter of choice.

• The way we learn what behaviour is valued and how, negative or positive, is a heuristic process.

• Our current assumptions concerning how behaviour is valued (positively and negatively) is determined by our mythologies: stories of explanation. These can and do develop as we learn and gain more experience. This development is often referred to as erroneously, as changing, new or different values.

Finally, we also acknowledge that people value material objects, goods and services. Whilst we recognise this as an emotional and important part of society it refers to the person–object relationship. I may value a house but it has no mythology about me. What we are discussing here is the content of social relationships, that is, person(s)–person(s) relationships where values and valuing occur from both parties.

It is our argument that these universal values form the deep bonds that connect human beings one to another. When we examine our evolutionary history, it is obvious that humans would not have survived as a species had they not been able to form and maintain social groups. The other species which co-existed with our earliest ancestors all had sharper teeth, longer claws, were faster, could jump higher and in general physically outmatch the earliest humans. Newborn human babies are extraordinarily vulnerable and dependent. They require a social group – a family or clan – to support them for years, or they will die. If this had happened too often, we would have become extinct and our present discussion would not be occurring. Therefore, we believe, that to survive humans had no choice but to evolve as social animals.

As social animals we needed (and still need today) a methodology to allow us to function as productive members of a social group. This is true of all social species. For example, the social insects have specific, complex chemicals that allow individual insects to function as productive members of a very coherent social group, for example, a beehive or an ant colony. These chemicals are their operating methodology and function as their heuristics and mythologies.

Central Proposition

We propose that all people, societies and organisations actually share the same set of universal values. We have articulated this proposition and the six universal values in various publications and articles, and they have been tested in commercial, public and not-for-profit organisations, and in a wide variety of communities and countries around the world by the authors and their associates.

Working with both the Hamersley Iron Organisational Development teams and Roderick Macdonald, we have identified six values which we believe make up the set of shared values which are necessary for the continuing existence of human social groups. Each of these can be thought of as forming a continuum from positive to negative. Behaviour at the positive end of the continuum strengthens the social group; behaviour at the negative end weakens and will eventually destroy it.

Most of a member’s behaviour must be at the positive end of the scale in order for him or her to be accepted and relied upon by others. Without such positive, reliable behaviour social groups must fail. Simply predicting behaviour is not enough. It is possible to predict that an individual will behave in a cowardly way, but such behaviour will weaken the group.

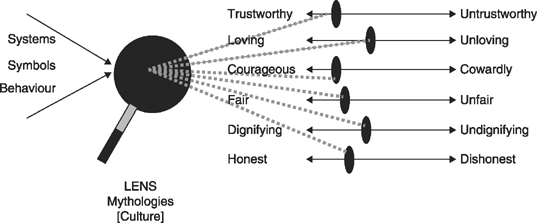

Figure 6.4 shows the values upon which we argue that all societies are based. These are the fundamental social qualities that underpin relationships.

The basic propositions are:

1. If a group of people is to maintain a productive social cohesion that lasts, then the members of that group must demonstrate behaviour that will be rated at the positive end of the continua of the core values by the other group members.

2. If a member of that group demonstrates behaviour that is judged by the other group members to be at the negative end of one or more of the continua of universal values, the person will eventually be excluded (although attempts to change the behaviour may be made prior to exclusion).

3. If several people exhibit behaviours that are similar, but judged by the rest of the group to be at the negative end of one or more of the continua of universal values, then the group will break into separate groups. This often happens with political organisations and religious organisations whose members break into ‘factions’ or ‘sects’.

Values, per se, cannot be observed. We can and do observe what people say and how they behave. All of us interpret behaviour and draw conclusions about the values that an individual’s behaviour demonstrates. Sometimes we have to wait for confirmation that our conclusions are correct, and sometimes we may be left in doubt. In some cases we may disagree with others as to how particular behaviour should be interpreted. In general, however, within a coherent social group, agreement is gained in time, often very quickly.

In essence, values are the criteria against which we assess our own worth and the worth of others. We argue that all people use these values as the basis for judging their own and others worth as they observe and interpret behaviour.

Consider a situation that might happen in any group. Imagine a group of people of which you are a member. You believe one of the other members has behaved in at least one of the following ways: told lies, stolen something, made fun of a less capable member, been indifferent to another’s serious misfortune, regularly failed to keep promises, demanded more than his or her share, or consistently avoided difficult situations. Is it possible for this person to maintain membership of the group if he or she fails to change their behaviour?

We cannot maintain a productive relationship with someone we cannot trust, or who is dishonest, cowardly, does not respect others’ dignity, and is indifferent to our feelings or unfair. It is likely that we and other members of the group will point out the negative behaviour, but if it persists, the person will be actively excluded from the group. This reflects the basic need of any group or society for predictable behaviour that mutually reinforces social cohesion.

However, specific rating of behaviour cannot be set in stone if the group is going to exist over time. We not only judge but also ask; if Josh has taken the last cake, why? For example, why would Josh think that his behaviour was fair? In other words any leader of a group and the other members must demonstrate their ability to understand the other, that is, be able to see the world from another’s point of view. This differentiates the mature adult world from the egocentric world of infancy and early childhood where the other’s needs are not seriously considered except to satisfy the self. It differentiates the fundamentalist position from that of reflective consideration. Not being concerned for the other is a classic condition of psychopathy. Others are manipulated for personal gain with no regard for well-being. It is the antithesis of productive co-existence, and destroys working relationships.

WHY THE SIX VALUES?

It is, of course, relevant to ask why these six? Over the years we have had many debates on this topic, both among ourselves and with others. First, the authors do not posit these as immutable and unquestionable. They are, however, related to two criteria. First, if there are other, similar words, are they already covered by the existing six? For example, integrity is a similar term but already covered by honesty and trust. Fairness and justice are very similar, but we prefer fairness because of the possible legalistic implication of the term justice. We have tested these core values in different societies including with indigenous groups, in different continents and in very different types of organisations – multi-nationals, churches, schools, voluntary organisations, local authorities, manufacturing, services, finance – and they have survived so far.

The second criterion is that a person’s behaviour may be judged to be positive in terms of one value but at the same time be judged negative in another. A manager may admonish a team member publicly for his or her poor work performance. The manager may be at the same time being honest, but showing lack of respect for human dignity. A soldier may admit fear and run away in the battle. The soldier is again honest, but may be cowardly and not to be trusted in combat. Another person may insist on the exact distribution of resources as authorised, believing they are acting fairly, but at the same time be indifferent to the greater or special needs of some individual or group. Thus, no two values ever (or should ever) correlate perfectly. If they did, they could be combined.

Thus we are saying that these values demonstrated positively are the defining properties of a cohesive social group. If members behave in a way that is perceived to demonstrate those positive values, then the group will remain cohesive. If members do not demonstrate such behaviour, that is, the other members regard their behaviour as a negative expression of values; the group will fragment and fracture. It is all but impossible to achieve any productive purpose over time if the group is not socially cohesive.

Some people are uncomfortable with the word love and prefer care. Of course in English we have one term to cover many meanings of a loving relationship. However, love is chosen because it is different from care. It is love that causes parents to sacrifice themselves for a child or a soldier to go out under enemy fire to bring back a wounded mate. As a corporate organisational development team member once said, ‘the difference between love and care is passion, good leadership is always passionate’ (Donna Loon, Comalco employee verbal comment 1991).

Sometimes we attribute these values directly to people; for example, he is a loving person. She is trustworthy. He is fair. She is courageous. What we are really doing is making a judgement about the likely behaviour of an individual. This may be based on direct experience, another’s report or reputation. What we are essentially saying is, ‘I expect that person to behave honestly.’ ‘I expect that person to behave courageously.’ ‘I expect that person to treat other people with dignity’, and so on. It is actually dangerous to infer that values are inherent properties of people, or that people inherently lack values. This false assumption leads us then to either idealise or objectify people, as is the case with racism and sexism. The only way of reducing these six values is merely to replace them with good or bad, right or wrong. That, we have found, is just too simplistic.

The values continua form part of our predictive model. They help to categorise behaviour and allow judgements to be made very quickly.

At the heart of these propositions, and any society, is the need to understand how others perceive the world and, hence, will judge behaviour. We do not choose to have these values. We argue that they are properties of relationships whether we like it or not. We cannot pick or choose. We cannot say ‘I will adopt these as our new corporate values.’ You are already being judged by them! This also means that should you adopt four, perhaps because honesty and courage are too difficult, tough luck! We might want to leave them out but others will not let us. These universal values are as oxygen to social groups. We cannot choose to function without them nor can we avoid demonstrating them through our behaviour. It is their very unavoidability that is cause for careful consideration by, in particular, all those who lead others.

Box 6.5

When Ian Macdonald was working in northern Canada with a First Nation community he presented the Values Continua and members of the community laughed. ‘Where did you get those?’ he was asked. They then went on to explain that they almost exactly represented their Grandfather Principles which have been (orally) handed down from earliest times and which guided their lives.

In another instance in Oman, the same author was thanked for including Islamic Values in the presentation.

Next we look at culture:

Principle 4: People Form Cultures based upon Mythologies

There is a wealth of literature today around culture: cross-cultural, multicultural, culturally sensitive. Culture is defined in terms of geography, religion, ethnicity, food, traditional dress, language, institutions, currency or behaviours (often called tradition), all of which can be both interesting and confusing at the same time (see Box 6.6).

Such differences can make discussion difficult. We have a simple definition of culture that is not limited by any of the usual boundaries. Indeed it transcends the usual categories. It is simply that people who share mythologies will cohere together in a social group forming a culture. We argue that mythologies form a stronger bond than the categories mentioned. For example the 2016 US Presidential election and the UK vote on membership of the European Union (Brexit) divided each country almost exactly in two. Each side having strong, emotionally driven mythologies not just about the issues but even more strongly about each other. A book by Joe Bageant (Deer Hunting with Jesus) examines the mythologies underpinning the cultures in the USA and articulates the process we are describing.

A very obvious ability of people is the speed at which we make judgements, especially judgements about behaviour. For example, a manager has very clearly explained to her department that absenteeism and lateness are unacceptable and that in future people taking days off sick without proper cause will be disciplined. A week later one of her team is late and then takes an unauthorised sick day. On return to work she reprimands him but after a one-to-one discussion, she does not take any disciplinary action. What do we make of this? Is the manager honest? Is it fair to the rest of the team? Is it loving towards the individual? Is it cowardly? Is she likely to increase or decrease trust? We might like to know more. Was there a special reason?

Although we often say that we would like more evidence, a common characteristic is that we often form an opinion on the basis of very little evidence. Two classic examples of this are (1) the remarkable ability of sports fans to be able to judge the accuracy of a referee or umpire’s decisions instantly, even from remote positions in the stadium and (2) the speed at which we make decisions about people at first meeting, the well-known first impression (Gladwell, 2005).

Although these examples stand out, think how quickly we all form views about the behaviour of politicians, celebrities or the police. There is now a huge business built around this in the form of TV reality shows where people are voted out of the house or off the island by the public. Why and how do we do this? A basic survival mechanism suggests that from the earliest times we had to quickly decide who was and who was not a threat. We had to judge whether the behaviour of a person makes them one of us or one of them, friend or foe.

Box 6.6 Definition of Culture

A culture is a group of people who share a common set of mythologies. That is, they share assumptions about behaviours demonstrating values positively or negatively. Essentially the more mythologies people have in common, the stronger the culture.

This is not to argue that all judgements are made this quickly or that, once made, they are irreversible. We merely make the point that human beings not only have the capacity but also the tendency to make judgements about behaviour very quickly, even if they are later reconsidered. How do we do this? The terminology that we use here is that we judge through our mythological lens (see Figure 6.5). In effect we all wear a pair of perceptual glasses. We see the world through a lens that refracts what we see onto the continua of shared values. That is, we observe behaviour and the lens directs that behaviour to be seen as fair or unfair, honest or dishonest, loving or unloving, and so on. Clearly this is not a simple bipolar rating, but the behaviour is placed somewhere along the continuum of one or more of the core values. If it is not, then it has no value and we are literally disinterested in it.

How is this lens formed? Our experience and research is consistent with other psychological research and common sense that suggests this lens through which we view the world is formed by our experience. It is formed as we are growing up and expands as we change. We learn from every experience, that is, heuristically: first from our immediate and extended family experiences; from our school, fellow students and teachers; from our community; from our workmates and bosses; from the media.

It is interesting to note that in biology there are very similar theories used to explain the development of perception and hearing. This is now seen as a very active process based on heuristically learned patterns. Essentially, mythologies are based upon perceived patterns. For example, a manager assigns a task. It is completed but he gives no feedback, thanks or recognition. This happens again. A pattern has started, it happens a third time and it is virtually a law. This person never gives any thanks. The mythology now is building that this manager’s behaviour is indifferent, undignifying and maybe even unfair. Now we have established a mythology, we have an unconscious tendency to do two things:

1. reinforce the mythology and

2. form a culture.

Box 6.7

Since the first edition of the book there has been a growth in research and development in what is called cognitive bias. This field of psychology reinforces our findings and propositions and articles give evidence of influences on decision making (Bless, H., Fielder, K. & Strack, F., 2004; Baron, J., 2007; Haselton, M.G., Nettle, D. & Andrews, P.W., 2005). Cognitive bias tends to look at errors in judgement and how we fool ourselves.

Our view is that these errors are in fact a natural process, the heuristics of creating mythologies by which we interpret the world. Our view is that the error lies in not questioning the judgement; but rather taking a fundamentalist or closed view.

This failure to remain open to other possibilities is disastrous in a leadership role despite our fantasy to idealise leaders as being decisive and unswerving.

Figure 6.5 Making Sense of the World through the Mythological Lens

We will now be sensitive to this manager’s behaviour and note every instance that confirms the pattern. We are also likely to discuss it with other colleagues and be most at ease with people who have the same view. There is great comfort in the phrase ‘yes, you’re right, I agree with you’. If we find someone who has received praise or recognition we can put this aside as a special case or the boss’s favourite.

This specific relationship and associated mythology can now, with reinforcement from others (the embryonic culture), become generalised. Now we build a mythology about managers at this company. This can grow to managers as a class and all sorts of evidence from history can be used to strengthen the culture and build mythologies. Now we know that ‘all managers are bastards’.

Although some people have argued that the term mythology implies the assumption or belief is untrue, this is a limited view of mythology. We have pointed to the combination of mythos and logos. We should also recognise that historically myths are stories that have a fundamental truth embedded in them (Campbell, 1949). Stories and myths have been told throughout the centuries to inspire people and to tell us how good people behave and how ‘bad’ people behave. They help to set and reinforce behavioural norms. It is not a question of true or false that would be used as evidence in a court of law, which attempts to be pure logos.

Children love stories; they demand that their favourite stories be read or told over and over again. In adulthood, the film industry and a large amount of television and entertainment are based on telling stories. Some of the most popular films, such as the Star Wars series, and books, such as Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings, are based on ancient myths that have been retold for generations. Even computer games have story lines with heroes and villains. All the major religions are based on books that essentially tell stories about what is acceptable and unacceptable behaviour.

Our mythologies give us a framework within which we can begin to organise our world and behaviour. They combine the story with its essential emotional component together with the logical, rational, scientific element. Thus our lenses are a combination of the two, neither wholly one nor the other.

This is of particular relevance in relationships when some behaviour or opinion is dismissed as illogical or emotional, as if rationality is the only, or, at least, the superior element. Underneath this dismissal is actually an admission of the failure to empathise with the other or to understand how they view the world. We ignore other people’s mythologies at our peril.

Thus we all have a unique pair of mental glasses with mythological lenses. One wonderful quality of such lenses is that we each have a pair that, apparently, accurately sees the world, while, sadly, everyone else’s lenses are slightly or significantly distorted. While all lenses are unique to the individual, they do have similarities with other people’s lenses. We all have experiences both of sharing opinions and of coming into conflict with others with different opinions. No one exactly matches our worldview.

Thus over time people seek out and form relationships most easily with people who share their mythologies, that is, share a view about how to interpret specific behaviour as positive or negative on the values continua. That is, they form cultures.

This definition of culture is quite liberating since it is free from many assumptions of what constitutes a culture.

The strength of the culture will depend upon:

1. the extent of shared mythologies – how much overlap there is among individuals;

2. the relative importance of these mythologies to those concerned; and

3. the context and significance of the issue/behaviour being judged.

Thus cultures, in this definition may well cross-geographical boundaries, ethnic association, organisational or professional boundaries. We would argue that not being precise as to the definition of culture leads to dangerous, even racist assumptions. For example, is there an African-American culture? Do all African-Americans share mythologies and to what extent? Do some African-Americans have more in common with people outside this category than inside it, and how do we express that? We often read or hear about ‘The Muslim Community’ or ‘The LGBTQ Community’ as if all in these categories share the same mythologies. They may not form a cohesive group at all and may actually have a range of mythologies some quite contradictory.

Many groups of people do have common stories, especially if they have experienced oppression. Mythologies created from oppression are rich in heroes and villains, and they have great strength and depth. It may be a false assumption, however, that later generations will necessarily internalise such mythologies in the same way as their earlier relatives. In fact, history is constantly being rewritten and re-evaluated based on contemporary issues and concerns (Becker, 1958). See also Joseph Campbell’s book The Hero with a Thousand Faces (Princeton University Press, second edition 1972).

There may be many different cultures within an organisation or ethnic group or country or age group. It is important to ask the same basic question: ‘What is similar about the ways in which these people rate behaviour?’ We must be careful about assuming there will be significant similarities just because a person is working class or male or first generation or Italian or in sales or whatever general and perhaps too-convenient label can be stuck to them. This is simple stereotyping that is a crude and often inaccurate grouping of people on the basis of one or two variables that may have nothing to do with mythologies.

Culture is subtler than that. Cultures may or may not be long lasting. Recently single-issue politics have produced an apparently diverse group of people who join together to resist an urban development or campaign for animal rights or against genetically modified foods and so on. At the other end of the spectrum there is a current anxiety with regard to what is termed globalisation, that international capitalism is creating a dominant culture that rides roughshod over less powerful and localised cultures.

Such concerns have been expressed, for example, in The McDonaldization of Society, by George Ritzer (1993). It is interesting to note that Ritzer explains some of the attraction for this process in terms of expanding predictability, for example, McDonald’s, Holiday Inn and other similar organisations that are almost identical wherever in the world they are located; including controlled internal climates, furnishings and services. This appeal is understandable in terms of the need for predictability discussed earlier.

We have stressed the importance of mythologies in creating culture. Indeed, we argue they are what generates a culture. We continue to argue for the need for clear definition, hence the choice and explanation of the term mythology. Essentially we are influenced from birth not just by what we observe but by the way we make sense and categorise these observations. This sense is a combination of the stories we are told and the rational, logical application of reason.

From this we are able to categorise and rate behaviour along the values continua. We are naturally attracted to people who rate behaviour similarly. Another part of the entertainment industry is based on this. Oprah, Jeremy Kyle, Question Time, Jerry Springer and other TV shows where opinions are sought and commented upon are highly popular. What you may notice is that such shows rarely produce any change in view. Their main function appears to be to reinforce views and assumptions and draw even clearer boundaries around cultures.

So far we have looked generally at these concepts. The next step is to look more specifically at how such cultures are shaped and changed.

We look at how behaviour can change, why we change our behaviour and what sustains that change.

Principle 5: Change is a Result of Dissonance

Through the use of our mythological lenses, which develops with experience, we learn to predict and how to interact with people and the world around us. Gradually, for most people a relatively stable worldview develops that is, for the most part, accurate in its predictions of how people and objects are likely to behave in their usual environment.

This does not mean that a stable or predictable world is necessarily pleasant or productive. As mentioned, children in abusive families learn to discern with necessary accuracy the patterns of abusive behaviour so that they might avoid them as far as possible. For most people a predictable, stable environment, even a relatively unhappy one, is actually preferable to an unpredictable one. It may seem odd to an outsider that a violent relationship continues, that adversarial industrial relations continue, that people repeat dysfunctional relationships. However, that is to underestimate the strength of the need for predictability, summed up in such phrases as ‘better the devil you know’, ‘out of the frying pan into the fire’. Habitual patterns of behaviour are hard to break, especially if they appear to be underpinned by economic necessity. So does this mean we are therefore captives of our mythologies caught in a repetitive cycle of behaviour where change is an almost hopeless uphill struggle? No.

There is, however, an essential ingredient that is necessary for change to occur and that is dissonance. Dissonance, a term which we use in the same way as Festinger (1957), is an experience where our expectations or predictions are challenged. To put it simply, the data does not fit. This could be a minor experience. For example, a recipe, apparently followed as before produces a sponge cake like a brick. More seriously, it could be when a trusted friend is deceitful. This is a challenge, major or minor, to our worldview. We have several ways of dealing with this depending upon the strength of our attachment to the worldview:

1. Denial. In this case we simply ignore the data. It is cast aside. It may be described by others that we are blind to his faults. Essentially we try to pretend it hasn’t happened. Denial is never completely successful and requires more and more energy to sustain, becoming more and more dysfunctional over time. Conspiracy theories are driven by the need to explain events that generate dissonance and require denial of the generally accepted explanation.

2. The exception that proves the rule. Here we move from denial but wish to maintain the original view. Therefore we need to explain it in terms of a one-off. There were unusual circumstances. The person didn’t realise what they were doing, didn’t mean it, didn’t see the consequences. If the person is a member of a group, for example, in an instance of police corruption, we might say that they are bad apples, or an unrepresentative minority.

If instances persist, these methods of defending our mythologies become ever more difficult and more disturbing. We reach a point where the difference between what we predicted and reality simply cannot be reconciled. This is the state of dissonance and we cannot tolerate dissonance for long. If the strategies of denial and exception fail we need a new explanation, a new predictive model. The manager really has changed and consequently we need to behave differently towards them. Paradoxically, once the balance has shifted, and a new mythology has been established, we may well then reconstruct the past to justify the shift. We remember other instances, which viewed with hindsight or more commonly with the new lens, did give us a clue. We now listen to others who tell us ‘I never thought he was that bad.’. Thus the new mythology is established and nurtured as carefully as the previous mythology.

THE THREE DATA POINTS: (BOX)

Dissonance can be positive or negative; it may be a ‘pleasant surprise’ or a ‘nasty shock’. Either way something unpredicted has happened. As mentioned the first instance may be denied or explained away as an exception. The second may be explained away as a coincidence, but a third occurrence is very difficult to deny. It actually implies a system change and therefore three data points will almost inevitably result in a new mythology. (See also below and Chapter 12)

It is very important to note that mythologies are not changed; new myths have to be built and prove useful but the old ones are always there to be called upon.

ORGANISATION-WIDE MYTHOLOGY

Perhaps one of the most significant examples of the process of mythology has been the revelations of sexual abuse of children in the Catholic Church (and other institutions). We take the example of the Church because it follows the process described above. First there is denial. The accusations are so contrary to the entire purpose and espoused intent of the Church, especially its leadership. Next we explain it away as bad apples or exceptions. Finally the evidence is so overwhelming that the dissonant views cannot both be held and we have to adjust our opinions and new mythologies are created.

There is a common assumption that people (especially in organisations) are resistant to change. Further, that this resistance is inherent. In fact, we have found people are remarkably interested in change. From an early age we are experimenting, trying new approaches, learning, testing. However, we are doing this in order to build a predictive model of the world. Apparent resistance to change is characterised by three factors:

1. There is no dissonance. Our predictive models still appear to work.

2. There is no association between the change and benefit to the individual. Why should I adopt this new approach when it appears more difficult and does not appear to result in any improvement for me?

3. There is a sense of helplessness. Although I do not like the situation, I feel that there is nothing I can do about it. For example, the demise of a business through market changes or a pattern of delinquent behaviour or addiction.

There is in fact a very good reason for this resistance to change. Without it society would become unstable through the failure of social cohesion and our continued existence as a species would be at grave risk.

Changing Behaviour: Systems, Symbols and Behaviour

From our experience and work over the last thirty years, we have argued that building a new culture and changing behaviour is the essential work of a leader. It is a key part of the work of management. Although many discussions of organisation assert the need to change an organisation’s culture, very little is said about how this is to be done in terms of specifics. We have argued that most of the material on this issue overemphasises the what but has very little detail on the how.

We identified that to bring about such change, the leader has three tools: Systems, Symbols and Behaviour.

1. The SYSTEMS of the organisation – designing and implementing systems with a constructive, productive purpose that are seen to be so by others.

2. SYMBOLS – described as the currency of leadership including badges, insignia, clothing, voice tone and so on to signify change or consistency.

3. Their own BEHAVIOUR – leading by personal example.

We note that this trilogy has become popular and has been used by others (Taylor, 2005).

In this section we deal primarily with the leader’s behaviour. Systems and symbols will be discussed later (see chapters on The Work of Leadership and The Process of Successful Change).

From the discussion above, the work of the leader is to:

1. Identify the mythology and the associated behaviour: you (the manager) are unfair and unloving because you never give us feedback.

2. Create dissonance: face up to the mythology and associated behaviour as if it is true (this can be painful). Don’t try to argue. Well, I know I do sometimes. Then create dissonance by behaving differently.

3. Continue with consistency: do not expect to build a new mythology on the basis of one new behaviour. Keep at it, and then keep at it again, and again.

4. Don’t expect behaviour change for some time: there will be a lag between the manager’s new behaviour and the building of a new mythology and new behaviours. Don’t be discouraged.

Dissonance is at the heart of all behaviour change (see Box 6.8). There is an old saying that insanity is continuing to do the same thing whilst expecting a different result. The work of anyone involved in changing behaviour is to demonstrate actual contradictions between expectation and reality.

Box 6.8 Factors Influencing Behaviour Change

In order for a person to change their behaviour, a person:

• must experience dissonance;

• must have a sense that the new behaviour will improve the situation (for the individual or social group);

• must have a sense that he or she is an active player in the process, that he or she can influence the process.

Until a new myth is established, even a single instance of behaviour that reinforces the old myth may destroy your efforts at change. Once a new myth is established, occasional deviations will be interpreted as that, deviations, not as instances of the old myth.

During the process others may not perceive the situation as you do. This too can cause them to interpret your behaviour in a way that is different from your own interpretation. You may believe you are demonstrating respect for dignity by your behaviour but your team may perceive your behaviour as demonstrating their dignity is only important when it is convenient for you, not when the chips are down. Therefore they perceive you as dishonest, lacking courage and not to be trusted.

We emphasise the importance of understanding other mythological lenses so that your behaviour will be seen at the positive ends of the continua of values through their eyes, not simply your own. One of the best ways to learn this is to come up through the ranks, to have experience at the lower levels of organisation and have learned how your friends and peers at those levels see the world. Another way to learn this is to spend time with your colleagues and/or employees, get to know them and talk about their views. A third way is used by the military, where sergeant majors have the role of interpreting the needs and beliefs (mythologies) of the troops to the officers. Whatever the method used, such understanding is essential for effective leadership that is able to build new mythologies, organisational cultures and behaviour.

We argue that a further element of the work of leadership is to turn dissonance into hypotheses, creating questions and possible answers where there is now uncertainty. Be aware, however, that the attempt to build mythologies carries significant risk. In fact as mentioned, mythologies do not really change; the old mythologies may recede into the background, may even be apparently forgotten, but they are likely to be present for many years. If behaviour slips so it can be seen to be on the negative side of the scales of shared values, the old negative mythologies will be stirred up and be more powerful than ever, since the newer mythology proved to be false and the old myth reinforced: We have been let down, it was a trick.

Some have suggested to us that knowledge of this model of leadership processes could make it easier for dishonest managers to fool their direct reports. Any manager, who believes they could do this, might like to try it. The process is subtle and unforgiving, requires constancy and consistency, people will spot a dishonest manipulator every time.

Behaviour alone, however, will not change the culture of the organisation as a whole. It can change the relationships between leaders and team members, but for overall change, the other tools of leadership – systems and symbols – must be engaged. These tools will be explained in more detail in later chapters. In the West we place an unfair burden and expectation on leaders to build a culture on the basis of their own behaviour alone. We idealise individuals then become disillusioned when they ‘fail’. We look too much for charismatic personalities. Without the use of all three tools of leadership culture cannot be built or sustained.

It is both a behavioural example and a symbol if a leader does not pick up litter, or, worse still, causes it, while at the same time extolling the virtues of good housekeeping. The leader may or may not be in a position of authority to change systems, but he or she can certainly try to improve them, if only by suggestion. Finally words of praise, a small gift/presentation/ award, contacting or visiting a sick worker may be symbolic examples which, if rated positively on the values continua, can support more substantive change.

Obviously some changes are more difficult to bring about than others. Years of industrial conflict may have undermined trust between workers and leaders to such an extent that a great deal of hard and consistent work may be needed to rebuild it. We have all seen in the past few years a growing cynicism around politics and politicians, an expressed lack of trust in the establishment. Mythologies have developed that we cannot trust politicians, they don’t respect people, they are dishonest and generally their behaviour is seen towards the negative end of the values continua. This has created huge divisions in society; these views are not based on rational argument but are visceral and deeply held. Such mythologies have driven the UK’s exit from the EU (Brexit) and the vitriolic US Presidential campaign (2016) where there was no dialogue, no considered argument, respect or compromise between the entrenched cultures. The extent and emotional depth of the mythologies, reinforced and refined through stories of events past, was strongly influenced by the process.

If people have already seen the contradiction (for example waste, poor practice, poor behaviour) but have not been in a position to do much about it, the promise of change may well be applauded. Change is more difficult where habitual behaviour has become entrenched – we’ve always done it like this, it is running to its full capacity, bosses are just like that. Nonetheless, change is always possible if there is both an understanding of how to bring it about and the will to do it.

Finally, there is no point in change if it can’t be maintained. Regaining trust only to be let down again results in an even worse situation than we started with. The negative mythologies will be reinforced.

In summary if we want to change our own or others’ behaviour, there are several key steps:

1. Understand the mythologies: why do people think that behaving as they do now is justified in terms of the values continua?

2. Understand the strength of the culture: how well reinforced are the mythologies in terms of stories and past events.

3. Identify how dissonance can be created. What behaviour, systems and symbols would be useful to demonstrate a contradiction between expectation (prediction) and actual events now? It is important to state that this cannot be based on trickery. There really has to be a demonstrable contradiction, say, between an old method of working and with safety; or smoking and good health; a mythology about leaders not telling the truth (dishonesty) and a genuine change that makes real information available that can be verified to be truthful.

4. Sustain the change with consistency. If the process has been successful, if changing behaviour has succeeded, it needs to be constantly and consistently reinforced or the old, habitual behaviour will return. It is crucial to remember that while in the change process new mythologies can be created, the old ones never die; they lie like silt on a riverbed ready to be stirred up again.

Dissonance need not always be negative. The positive aspect of a shift of balance can be summed up in the phrase the penny dropped, or the light went on. Change of behaviour occurs when our expectation changes as a result of changing our internal predictive model, but this is often not an easy task.

As we argued in Chapter 3, when considering behaviour change, it is as important to understand social process in detail, as it is to understand the detail of technical process.

If someone wanted to build a road bridge across a river, make aeroplane engines, prescribe drugs for the sick, run a railway or drill for oil, there would be no doubt that the person would be required to demonstrate a detailed knowledge of the technical process to be used and the theory behind it. Considerable alarm would be generated if, when discussing the safety of a nuclear power plant, a group of people with little experience and less technical knowledge claimed that they would decide what was safe by using common sense. ‘Oh’, says one, ‘I think we should put the waste in big, secure containers.’ ‘Yes’, says another, ‘and I think those containers should be metal, perhaps steel with some good locks.’ ‘Yes’, says a third, ‘my experience is that some good steel should be fine.’ After a while a member of the group who has been silent says, ‘Perhaps we should be more specific? What sort of waste will this create? Will steel be protective enough?’ Then the person has the temerity to start discussing isotopes, half-life, contamination and degradation of crystal structure and strength by radiation.

He is told not to be so pedantic and so theoretical. This is, we hope, an absurd scenario but, when translated into a discussion about social process, it is not quite so unrealistic.

‘We need someone to head up the new marketing division for the UK.’ ‘Yes, we need someone with experience, and good leadership qualities.’ ‘Yes, someone who can get real results. Those marketing types can be difficult. There are some real prima-donnas in the marketing department.’ ‘What about Johnson from head office?’ ‘Not a bad idea, she’s really bright and has had some experience in Japan’. ‘Yes, but she’s a bit young. Will she be able to impose herself?’ And so the discussion goes on. Terms are used with little definition. There is an assumption about shared meaning, but it is not tested in any rigorous way. Critical decisions are often made on the basis of such common sense and pragmatism, which is so highly prized over theory. Why is this so, especially when compared with the value of theory and detail in technical areas? There are three main reasons for this:

PEOPLE–PEOPLE RELATIONS ARE ACTUALLY MORE COMPLEX

Although there are references to people–people relationships as the soft areas and technical issues as hard, this is misleading. These soft areas are often highly complex and difficult to explain. Unlike objects, we cannot effectively ignore people’s purpose, will, mythologies and culture. These are all less easy to observe and manage than objects’.

THERE IS A LACK OF A SHARED LANGUAGE

While there are universally accepted definitions in many of the so-called hard sciences, this is not the case in social science. There are no generally accepted theories in the sense of clear expositions of principles with predictive validity.

Instead of a rigorous and agreed set of terms and definitions, social science and perhaps, particularly organisational theory, is subject to fads and jargon. All disciplines have scientific language, which may not be easily understandable from outside. However, in the area of organisational literature there is a suspicion that jargon is used in a deliberate attempt to make something that seems to be simple appear more complex and technical than it seems. Another suspicion is that jargon is used to make something that is unpleasant more palatable or acceptable. In the military, killing your own troops is friendly fire; killing civilians is collateral damage. As George Orwell and others have written, language can be used to clarify or confuse or simply mislead. Many politicians have used language to deny reality or reinvent it. We are now told we live in a ‘post truth’ time where ‘alternative facts’ (lies) are insisted upon as truth. As someone once said ‘are you going to believe me or your own eyes?’ We believe this process has always been present and is an essential part of the demagogue’s use of power.

WE ALREADY HAVE OUR OWN THEORIES ABOUT SOCIAL PROCESSES

As we have said previously, we all have our own theories about people. We do not start with a blank sheet when considering social processes. Thus, any outside theory of social process will be judged against our own theory, any predictive statement is compared with our own. As explained in the discussion of values these theories may be deeply embedded and very emotionally charged. To propose an alternative is not an innocent or even purely rational process.

If a change process is to be managed, it is critical that there is a shared understanding of how to analyse social process and how it can be influenced effectively.

Many of the criticisms of business process re-engineering can be seen as pointing to a failure to take into account the need for a detailed understanding of social process.