CHAPTER 9 Levels of Work Complexity

Organising Work

Large organisations are characterised by layers or levels of structure. We refer in general terms to shop floor, operators, even workers. We talk about supervisors and first-line managers, then middle managers, executives, managing directors, vice presidents, presidents, chief operating officers and chief executive officers. In the civil and public service and the armed services there are ranks and grades forming a quite deliberate hierarchy. Even in smaller organisations there are managers and reporting structures. People over the years have criticised or attacked hierarchy but it is surprisingly robust and can be traced back through history (Jaques, 1976; 1990). Notable writers such as Weber, 1922; Blau and Scott, 1962; Burns and Stalker, 1961; Dawkins, 1976; Lane, 2006; Mintzberg, 1979; Morgan, 1986; Simon, 1962; Whyte, 1969 and many others have all described and analysed this organisational feature.

Like Jaques, we regard this form not as coincidental, but as indicating a deeper human requirement and a potentially effective and constructive way of organising work. Also, like Jaques, we see many current fads, criticisms and alternatives as misleading, sometimes vacuous attempts to cash in on the fact that many hierarchies are not nearly as efficient or effective as they could be, often because several different concepts are muddled together to form a tangle, which is not easily unravelled. To quote Jaques: ‘The problem is not to find an alternative to a system that once worked well … the problem is to make it work efficiently for the first time in 3000 years’ (Jaques, 1990). We are sure that there have been examples of hierarchical structures working very efficiently and constructively over the last 3,000 years, or the concept would have died out centuries ago.

What is muddled?

When people design, operate or criticise organisations, they can confuse several quite different, albeit related, elements:

1. Level of management: The underlying structure of an organisation is actually a structure of management; as such it is an authority structure. It defines or clarifies who has the authority to:

a. Require someone else to carry out some work (assign tasks).

b. Review that work and apply consequences (positive or negative) in the form of recognition and/or reward.

c. Depending upon work performance or upon a changed context, begin processes to remove a person from a role. (The corollary being the manager also authorises the person into the role.) This is what Jaques so clearly identified and with colleagues, including the authors, researched in many organisations. They found similarities across organisations in many fields of endeavour.

Grades (or ranks): Many organisations (perhaps most obviously in the public sector) also have grading structures; these do not automatically confer authority over others but are primarily concerned with career development and/or salary and purport to recognise differences in skills or qualification. These operate within management levels. For example, in Figure 9.1 there are actually three levels of management. Manager A manages B1, B2, B3 and B4, but note that B1, B2 and B3 are differently graded. There are invariably severe repercussions if B1 thinks and behaves as if he or she is actually the manager of B2 and/or B3 by assessing their performance, issuing instructions and so on. B1 is, however, the manager of C1, C2 and C3 (who are also graded differently). Note that C1 and C2 are not actually managers at all (perhaps stand-alone technical specialists) while C3 manages D1 and D2.

There is a dangerously implied hierarchy of authority in grading structures which causes significant distress, anger and resentment: pulling rank, overbearing, the exercise of power: these are multiplied when movement through grades is purely based on seniority or time served and has no relation to ability or achievement.

2. Complexity of tasks: All tasks have an inherent complexity. We all recognise this in terms of how difficult we find a task. The critical factor here is to separate out skill and knowledge from the underlying complexity of a pathway to, or method of, achieving a goal. If we imagine that there are thousands of tasks that need to be done in an organisation, it makes sense to order these in some coherent way. This is almost always done by gathering or bundling tasks of equivalent complexity together and calling that a role. We have found this concept adopted across organisations, regardless of whether they had any notion of work complexity.

3. Mental processing ability: As explained in the previous chapter this refers to the ability of an individual to complete tasks (or solve problems) of a specific complexity. This too varies. Some people will be much more comfortable with tasks of a particular complexity than others.

It is fundamental that we distinguish between these concepts of managerial level, grade, complexity of task and mental processing ability. While they are clearly distinct, there is also a fundamental and critical relationship between them.

How Are They Related?

To answer this question, we must ask why a hierarchy of work underpinning organisational structure, despite its many detractors, is, and has been, so prevalent. If the purpose of an organisation is to provide the goods and/or services then such a depth structure is or can be the most effective. Over time, many forms of organisation have been tested and the managerial structure based on a hierarchy of work complexity has been found to be extraordinarily resilient. Our experience and work supports Jaques’ basic propositions that this is for two main reasons: first, that tasks can be categorised into qualitatively different types according to their complexity and second, that this reflects the way people construct their worlds, that is, the way they process information.

A careful consideration of Jaques’ propositions shows them to be closely related. Work is a construct of the human mind; we see the world as each one of us constructs it. Some people are able to make sense of numerous variables interacting simultaneously, others are not able to do this and generate a much simpler representation of the chaos in which we are all embedded.

The distribution of work through all organisations is a recognition that different people are capable of different work, even though very few organisations have a clearly defined concept of differing work complexity. In no organisation do we find a random distribution of work to roles, but rather a very definite distribution of work to roles at different levels.

In Chapter 8 we outlined our definition of human capability and gave examples of how this was demonstrated by people doing work. We described how for one person a malfunctioning piston is technical hands-on repair; for another it is a reflection of how the vehicle is driven and for a third it is a design problem or transport issue. Each perception is relatively more abstract.

Thus we see that mental processing ability, an individual quality, gives rise to an analysis and solution of a particular complexity. Tasks of similar complexity can be bundled together to form a role that can be placed at an appropriate level in the organisation (level of work). This is what organisations do now, often in a muddled way because they do not have a clear means of differentiating between levels of management, salary grades, complexity of tasks and mental processing ability.

Being clear about these issues allows each level upwards to reflect a qualitatively more complex and abstract way of perceiving and acting in the world of work. More importantly we have a specific rationale for the generally vague term of adding value. Each level, potentially, adds value to the work of the level below by setting it in a broader, more complex context.

This is what employees intuitively refer to when they comment as to whether the person in their manager’s role adds value. Most critically, in terms of power and authority, if the manager does add value, it is more likely that the team members will accept the manager’s authority. This is in contrast to the power exercised by the more senior, higher-graded colleague who adds no value through his or her work and is resented.

We have referred to these levels of work: qualitatively different types of complexity of tasks and mental processing ability. How to describe and recognise them is, however, not easy. Jaques, with the authors and many others, especially Cason, has described these levels and mental process in slightly different ways (see for example General Theory of Bureaucracy, Requisite Organisation, Human Capability Theory). We have laboured also with the help and input of many others to generate our own descriptors, which have been articulated in published and unpublished work, often for specific organisations. There are two issues here. The first is what we mean by qualitative differences, or discontinuities in both the complexity required to complete tasks and the mental processing ability of people. The second issue is how to describe such discontinuities in a way that is useful. By discontinuity we mean that an approach or method is fundamentally different in kind from another. It is not simply faster or increased volume. Think of the difference between a bicycle and an internal combustion engine.

There is ample evidence of discontinuity in the way that people order their worlds and go about their work. In the book Levels of Abstraction in Logic and Human Action (Jaques, Gibson and Isaac, 1978), chapter 2 describes a range of theories of discontinuity and compares them; chapter 17 (by Stamp) compares a further range of theories including Bennett (1956–1966) on mathematics, Bloom (1956) on education and Kohlberg (1971) on moral development. Further theories even more well-known such as Piaget (1971) and associated researchers have hypothesised and experimentally demonstrated such discontinuities in the way people perceive and act in their worlds. Stamp (in subsequent work) clearly describes similarities between the discontinuities found in her own work and that of Jaques, Macdonald and others. The summary of the descriptions is shown in Table 9.1.

Whilst these are general descriptors, there is a need for those trying to design and run real organisations for more precise, behavioural descriptors.

After some thirty years of effort, including years of work with Jaques, Stamp, Rowbottom and Billis, the authors believe that the perfect set of descriptors is somewhat like the search for the Holy Grail. The difficulty in coming up with perfect descriptors stems from two causes. First, any description in words will be ambiguous because of the inherent ambiguity of words, and their changes in meaning over time. Second, we have found that useful descriptors are best written and most readily understood in the context of a particular organisation, describing work in terms of that organisation. Thus, we see a comprehensive set of descriptors for the work of social services in the UK by Rowbottom and Billis (1977).

Despite these reservations, the following is an attempt to provide a general set of descriptors. Again, like Jaques, we note the importance of time to completion, what Jaques called time-span.

The further we look out, try to predict or plan for the future, the more uncertainty we have to manage. Complexity increases as we project into the future.

However, we have also found instances where due to the rapid change in the immediate environment, for example in the chaos of combat in war, complexity is also very high in short time periods.

Stewart argues that what time-span is measuring is the length of time a person can make order in a chaotic universe. We now believe time-span measures the time to disorder, which appears to have a relatively stable pattern in what we would consider normal environments. As the environment becomes more chaotic, the time to disorder at all levels is compressed, as in war or in emergency situations.

Whilst we agree that a task which will take more than three months to complete will be more complex than a task of type one complexity, there may also be tasks of high complexity that have to be completed quickly if they are to be done successfully. For example, reacting to the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

Below are our general descriptors of each level of complexity.

LEVEL I – COMPLEXITY I (R1)

Box 9.1 Level I

Hands on – completing concrete procedural tasks.

Typical tasks might be completing forms, cleaning a room, servicing a vehicle, entering data. The completion of tasks at this level does not take longer than three months.

At Level I there is direct action on immediately available material, customers or clients (see Box 9.1). There is a clear understanding of the work to be done, the procedural steps to be followed and how they are linked. Direct physical feedback indicates whether the work is being performed correctly. The work is often immensely skilful, with significant use of practical judgement, discretion and adjustment by touch and feel or trial and error if previously known solutions or learnt troubleshooting methods do not work. A known pathway is followed until an obstacle is encountered and then practical judgement is used to overcome the problem or assistance is called for.

Useful input to improving working methods can be expected from the day-to-day experience built up, sometimes over many years, by using the procedures, the observation of repeated patterns of concrete events, and from trial and error. The patterns observed and described are all physical events.

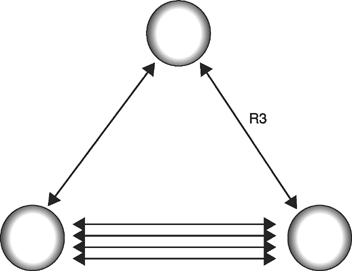

Relationship one is direct. The person and their work are rarely separated. This also gives rise to the reality that people doing this type of work do not take their work home. At the end of the day or shift the person goes home and leaves their work until their next shift.

LEVEL II – COMPLEXITY II (R2)

Box 9.2 Level II

Monitoring and diagnosis of operational processes.

At Level II, the key work is diagnosis whilst observing people or events, working in with established, known systems and processes (Box 9.2). Significant data collected in the form of suggestions from those operating the process and from the flow of concrete events observed in the process are compared with a known model or system. Improvements and modifying actions may be taken on the basis of this information. Diagnostic patterns may be learned through training and education, for example, in engineering, social work, financial analysis or nursing, or through years of experience. Indicators of learned patterns (algorithms and systems) are sought to recognise significant data and so identify the specific pattern or system that is operating in this instance in order to formulate alternative methods of performing tasks, to decide whether the diagnosis is correct or that the case is from another pattern.

This and the general work of task assignment demand the mental construction of how tasks might be envisaged and solved without direct physical, hands-on feedback. Trial and error solving of problems will not be sufficient. Problems are treated as a particular case fitting a known type rather than a new trend or pattern needing identification of a system. Every case is unique.

There is still direct access to the area of work and often-physical contact with the work. Leadership roles characterised by work at this level will include managing those who are operating the production process and applying the systems and so will have regular direct contact with them. They will be accountable for ensuring that the work of those they are managing is not constantly interrupted so that they may achieve their outputs reliably.

Here the person now can reflect (R2) on the work (R1). They can think about it away from the activity. They can mentally compare ways of approaching it. This is the first level of real planning and the first level of professional work associated with teachers, social workers, nurses, solicitors and others. Such work examples include designing individual care or teaching plans for individuals, comparing and identifying different ways of servicing vehicles.

LEVEL III – COMPLEXITY III (R3)

Box 9.3 Level III Focus

Discerns trends to refine existing systems and develop new systems within a single knowledge field.

Work of III complexity requires the ability to recognise the interconnections of significant data from a flow of real events within a single knowledge field, or discipline, and to discern the linkages between them. Trends are developed and systems are derived to mesh the interlinked activities in a way that will achieve the desired end result. The process is one of conceptualising alternative means to achieve a goal by forming, if this, then that – if that, then the other, chains of hypothetical activities that are tested through to completion. Alternatives are seen as either/or. This system which best addresses the current situation and links it to projected desired objectives is selected, taking into account local conditions, cost, risk, time to completion and the need to conserve human and material resources.

Because the work of hypothesis generation and test remains within one knowledge field, Level III capability will not recognise the often confounding effect on the proposed system caused by variation in another field generated simultaneously by the activity of that proposed system. Information that arises from what is not there (negative information) is not recognised as significant. The inability to comprehend the simultaneous effect of planned activity in other fields causes many system failures.

Work of III complexity can create high efficiency productive systems or optimise existing systems through the application, for example, of rigorous cost analysis, work method development and risk analysis. III complexity work is well suited for the leadership of a department of up to 300 people in a typical enterprise, recognising that geographic spread, technology variation and work type all have a bearing on the number of people and resources being managed. It is also well suited for highly specialised stand-alone roles requiring great depth of knowledge in a particular discipline.

Here the triangle is completed. The person here is able to consider the difference between a special cause or one-off and a systemic cause. That is the system itself is at fault or needs improving. This level is suited to Lean Manufacturing, analysis and interpretation of actual data, benchmarking and comparison. However it does not go into the abstract world of imagining what is not there or does not currently exist. It is the world of best practice or rather, common practice and is the bread and butter of many large consultancies.

At Level III, work turns into the development of an understanding about the nature of the relationships between concepts and or physical phenomena that make up a specific domain or field of knowledge, held in the mind of the person doing the work. The knowledge is expanded through time as a result of work and the exposure to new knowledge. This expansion of knowledge can lead to the appreciation of potential new systemic relationships within a field which are then examined.

As new understandings of the interrelationship between entities in the knowledge field are developed and confirmed, they are then applicable as a predictive mechanism for future action.

Whereas work at Level II requires the determination, of which previously learned systemic relationship fits the data discernibly in a particular discipline or field of knowledge, work at Level III is the determination of the systemic relationships that exist between the data that is available and then the search for data from the field to confirm the relationship. Such data is often not readily distinguishable and may need to be searched out to prove or disprove the validity of the systemic relationship hypothesised.

Within the individual knowledge domain, work at Level III is that of system construction and while this ability is a powerful mechanism for producing order from chaos, it also leads directly to a significant trap as follows.

In most instances it is possible to see, after a more complex problem has been solved by someone else, how it could have been solved by the application of Level III problem-solving methodology: If only those additional pieces of information had been available to me and I had more time; If I had known those elements were part of the knowledge field. Sadly we do not live our lives in hindsight.

A distinctive element of work at Level III is the non-appreciation of the simultaneous effect of variation from several different knowledge fields upon the problem at hand.

A maintenance manager who can work effectively in a Level III role will be able to optimise the direct cost of repair by effectively systemising a repetitive major maintenance activity. However, this solution will not be one that will incorporate the effect on the capital cost to the enterprise and the other ramifications of holding a greater or fewer number of spare components available in stock for immediate use. Nor will it allow for the social impact of requiring a maintenance team used to diverse work being required to perform repetitive work.

It is the inability to appreciate the simultaneous effect of variation in other domains upon the apparent domain of the system that results in the law of unexpected outcomes and gaming the system.

The field of knowledge, or domain, that is most frequently missed when it comes to the carefully considered systematising of work, when it is done at Level III, is that of the people, the social domain. This results in systems of work that are designed to deliver a superior outcome but fail to do so due to no regard being given to the effect caused by the interaction between the designed system and the people upon whom it impacts in their work lives. This leads, invariably, to short and long-term financial and social detriment, examples of which abound in our regulatory and legislative environment.

LEVEL IV – COMPLEXITY IV (R4)

Box 9.4 Level IV Integration

Integrating and managing the interactions between a number of systems.

At Level IV there is a need to imagine and construct relationships between systems that are working in parallel and simultaneously, in order to develop a functioning set (Box 9.4). This demands a quality of thinking that crosses and integrates a number of fields or disciplines (if this and that, then the other) in order to see the risks, benefits, costs and potential delays. A key feature is that this integration may well involve a sacrifice in the effectiveness or efficiency, or both, of the functioning of one or more of the systems or processes so that the overall set works more productively. The language is often of trade-offs and conflicts. Thus, being able to identify and predict conflicts, some or all of the systems may need to be modified or adapted. Alternatives are seen as both/and rather than either/or.

This is often referred to as the first strategic level where an organisation’s policies have to be understood, articulated, expressed and promoted in the design and operation of an integrated set of systems. Things, however, may not be as they appear. Production rates may be up but the facility may still be in trouble. Negative information is significant and made use of. Design and monitoring of a range of systems at this level has to be done without being able to observe the entire physical area of work.

Level IV is also the first level of sacrifice where resources must be sacrificed in order to achieve priority objectives. In business this is typically money or time. In the military it is far more difficult, as a commanding officer must send men and women he has trained and knows well into a situation where they are likely to be killed in order that the overall battle may be won. Officers who have been in this situation have described the incredible pain of doing so. (At Level III, leaders will try to conserve resources even when this leads to a bad outcome.)

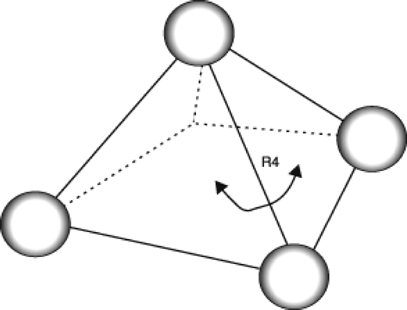

Imagine now a pyramid. The R4 complexity means that the person must imagine how one system impacts or might impact on another from a different field. A person may be imagining what the social implications are of a Technical Change (see Chapter 3). This is the first real level of systems design since most organisations have systems interacting with each other. We might think of this as system design that appreciates and allows for the effect of first order consequences.

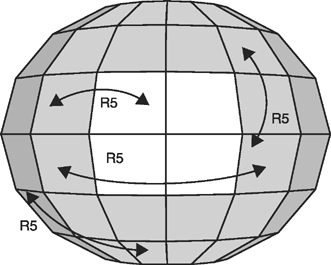

LEVEL V – COMPLEXITY V (R5)

Box 9.5 Level V

Shaping and managing an organisation within its environment – maintaining the organisation’s systems and processes so that it is self-sustaining within that environment.

At this level, entire theories and not just principles are used to link multiple knowledge fields or disciplines (Box 9.5). As a result of understanding and predicting the environment, the organisation is modified to address and minimise any potential negative impact (social, political or economic) from the environment, for example, by deciding what line(s) of business the organisation should occupy in five years’ time, and managing the effects that a change of direction will have by changing the systems of the organisation and the capability it has to meet the new conditions, while ensuring the organisation is still achieving its purpose. Whilst not only being able to construct the relationships between systems, the second-order and third-order consequences of those relationships will also be foreseen. This includes understanding what impacts changes in another part of the organisation, of which this entity may be part, may have on its productivity and viability over time; understanding what impacts systems may have on people. Management by example and the use of symbols are crucial tools.

At this level, the entity, for example a whole business, constitutes an accepted whole with a complete boundary within the external environment. Consequently, work at this level is associated with boundary conditions and the interactions between the environment and the entity. The objective of leadership at this level is to have the organisation maintain a productive contact with its environment – economic, social, cultural, technical, legislative, natural – as this boundary changes.

The work will involve complex organisational projects such as major information management systems and new technological or people systems. The data on which the work is based is both abstract and concrete, observable and unobservable, with a need to recognise remote, second or third-order consequences and multiple linkages between cause and effect. Negative information, the absence or non-availability of specific data, i.e., what is not there, becomes much more important and is used extensively.

At Level V the pyramids have formed a sphere with all the apexes at the centre. We have a complete system. At this level the work involves understanding and predicting consequences and impacts of change in any one part of the system on ANY other. Thus R5 encompasses the system. We are now in the world of second-order consequences. It is interesting to hear how often politicians or leaders will refer to unintended consequences. They may claim ‘we could never have predicted this’. They dismiss criticism by saying ‘only with the benefit of hindsight’. In fact our view is that such unintended consequences are the result of poor analysis, over simplification of a complexity IV or V problem being reduced to complexity III or below. A classic example being George W Bush’s comment ‘Mission Accomplished’ in Iraq in 2003.

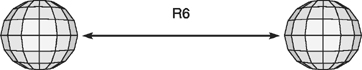

LEVEL VI – COMPLEXITY VI (R6)

Box 9.6 Level VI

Shaping the organisation of the future – creating the ethic on a national and international basis that allows entities to function and manages the relationships between entities of a significantly different character.

The work at this level demands direct appreciation of and interaction with the external social, political, technical and economic environments in order to influence and mitigate any possible negative impacts on the organisation/businesses, or promote changes that will be to its advantage (Box 9.6). Essential to this is constructing an overall framework in which the relationships between fundamentally different types of organisations can be understood and managed. This may involve managing the relationships between two organisations built on very different organisational assumptions, principles and purposes, such as the relationships between a commercial company and government or a mining company and an indigenous community. It also involves the ability to form relationships by understanding sometimes very different perspectives and how they might be addressed productively. Managing this framework of relationships enables you to construct policies that influence and, if done well, enhance the organisation’s reputation, often internationally. Level VI requires the ability to build mutually beneficial relationships between people from organisations with possible competing purposes. It requires the ability to construct mental models that are entirely new. It often is characterised by the ability not only to handle, but to live with, even enjoy, paradox.

Compliance with the legal framework is insufficient at this level; ethical frameworks for behaviour need to be created through the development and application of policies and systems, which will make the organisation acceptable within its environment over the long term. Such actions may well be seen as an unnecessary burden in the present. The organisation does not simply comply with local laws, such as those involving child labour or safety but sets its own (higher) standards.

Long-term goals are set and policies and corporate systems are shaped and audited to achieve them. If this work is not done well, organisations are constantly exposed to unexpected, major, destabilising problems, which distract attention and drain energy from the business. If done well, this work will add significant national and international value to a brand or reputation over time.

The work at this level is often seen as political and involves building constructive external relationships with relevant leaders and opinion formers. Within the organisation, leadership will be demonstrated primarily by symbolism and observable example.

R6 looks very much like R1. However, instead of the poles being a person and their work, the poles at Level VI are made up of level five entities.

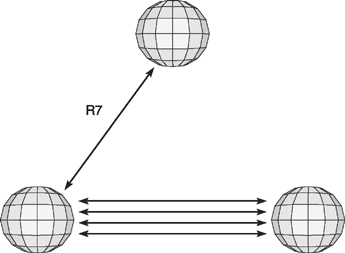

LEVEL VII – COMPLEXITY VII (R7)

Box 9.7 Level VII

Sustaining a successful long-term future by understanding, predicting and influencing worldwide trends that will affect the viability of the organisation.

The work at this level entails comprehending the fundamental forces driving changes in the environment (national and international). These are worldwide trends that affect economic, social, political, technological, environmental and intellectual forces as they come to bear far into the future. On the basis of that understanding, predictive hypotheses are developed to position the multinational or major organisation or corporation; working at Level VII involves taking account of these fundamental forces, constructing long-term plans and actions for the organisation’s growth and viability. This will involve the creation of new Level V entities and the winding down of existing Level V entities pre-emptively as a result of the development of institutions, relationships and interactions within societies and technologies. The work at this level of complexity requires the ability to appreciate the unknowability of future worldwide contexts and to allow for this in generating the various possibilities, which can be realised, for your own organisation; providing goods and services for potential, entirely new, markets well into the future.

Leadership of an organisation at this level entails the creation of an ethical framework that will allow the organisation to thrive in its various social environments: we have to do what is right. There is a demonstrated concern for the whole of society and not just narrow self-interest in the behaviour of the organisation and its people. The setting of the ethical framework may be for a whole sector (non-governmental agencies, banks, manufacturing), and not just for their own corporation.

R7 looks very much like R2 except now the person is reflecting upon ways of building level VI complexity, mutually beneficial relationships. We are now generating theory.

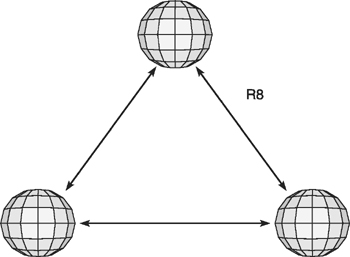

LEVEL VIII AND ABOVE – COMPLEXITY VIII (R8 +)

Box 9.8 Level VIII

Creating worldwide institutions that enable fair governance on global issues: conflict or climate change.

We can continue to describe ever more complex work and relationships. Technically we can do this ad infinitum through the diagrams. We may be able to describe the work but it is ever more difficult to find examples of people who can actually work at such levels.

Level VIII complexity is such that it requires the building of level VII and level VI organisations (See Box 9.8). In effect it is creating the worldwide institutions (systems) that can deliver justice and good government. Attempts have been made, some much more successful than others. One example is the United Nations. It is of course flawed in its own title, as the nations are representative of their own views not integrated into a transcendent organisation that operates globally. Other examples are the World Bank (etc.). We might criticise them but they are trying to address quite the most complex problems on Earth: conflict, wars, poverty, climate change and population growth.

The poles at this level are represented by complex institutions and social theories of human organisation and existence.

All Levels of Work are Essential

While we can recognise the extraordinarily high Mental Processing Ability of certain individuals, and it may be interesting to speculate as to who they might be, the vast majority of us work at less exalted levels. This does not mean we have less worth as human beings; it simply means we pattern and construe the world differently and that we have differing abilities to carry out work.

The environment presents us with problems that require the application of all levels of work discussed and, perhaps, more. All these levels of work are essential if a society is to survive and thrive over time. If a problem requires Level IV capability for its solution but an MPA of II complexity capability is applied to solve it, the result is failure.

People and societies do learn from trial and error, but at a cost. With effort, time and the correct environment, a useful solution to a problem can be delivered, and providing the effect and cost of error is not too damaging to the person or the society, such a process of problem solving can be tolerated. If there is not time to learn from this process or if the results of the inadvertent experiment are too disastrous, there may be no person, business, or society left to take advantage of the result. If the environment presents a problem and there is no one who has the mental processing ability to deal with it, the society will be damaged or fail.

If businesses, government agencies and non-profit organisations are to meet their goals and survive, they must have people within their organisations who can work at the levels required to achieve their goals in their respective environments. The quality of work carried out at all levels of the organisation will determine the quality of results obtained. Thus, as human beings, we should delight in all levels of work. We all have something to contribute to the whole.

Role and Person

Under normal conditions, all work roles have minimum mental processing requirements, if the work of the role is to be performed successfully. Individuals who fill those roles, however, may or may not have an ability to match those minimum requirements. There are people in roles with requirements that exceed their mental processing abilities; others are in roles that require less than their full mental processing abilities.

The issues that surround the match, or lack of match, between the capability of the person and the complexity of the work of a role are of vital importance to the organisation, which must set up and operate systems to deal with them. For example, what does the future CEO look like in a Level II role a year or two after he or she has joined the organisation at age 24? How does this compare with another individual who will be happy and productive in a role at Level II throughout her career? These are issues for career and staff development.

These are not issues, however, which bear upon the concepts embedded in the levels of work complexity save that overriding concept of work being a construct of the human mind as it seeks to build order from the chaos of the environment in which the individual is performing the work.

The level of work of a role does not tell you much about the MPA of the role incumbent. If the person is successful in role, it is safe to assume they have the required knowledge, skills, application and MPA. Beyond this minimum, the role the person currently fills tells you little about the person’s MPA. Should you have the opportunity to examine closely the work a person is doing in a role, how he or she does the work and why it is done that way, you can make a judgement about the MPA the person brings to the role. This is not, however, a simple exercise and it is always a judgement, not a certain determination. This is a very good thing because it makes it clear we cannot pigeonhole people based on their current job. Because the question is always open, the intrinsic humanity of the individual is easier for all to respect.

It is important that the terminology must always be ‘a person in a Level II role’ and never a ‘Level II person’ (see Box 9.9).

Another Perspective

Another way of looking at complexity and level of work is to think about what it is reasonable to expect from someone in that role. As we have discussed there will be occasions where the person in the role has a higher mental processing ability than is currently required. However, here we might look at what it is reasonable to expect from anyone in that role if they are doing the work appropriately.

One way to think about this is to consider what might happen in the case of a disaster or a serious safety incident. What questions would it be reasonable to put to somebody in a particular role?

If we consider a Level I role then it would be reasonable to ask the person if they followed procedures that they had been trained in. For example we might say ask: ‘When the dial went into the red zone did you shut the valves four and five as in the operating procedure? Did you then inform the supervisor and other operators that this procedure has not reduced the temperature and the situation was becoming extremely dangerous?’ If the person has been trained and followed all the procedures as taught then, even though a disaster may have resulted, it would be unfair to attribute blame to the person in the level I role; after all they did their work.

It is also an interesting characteristic that in level I roles we do not ask people to write reports or formally propose written recommendations. In such roles we ask people to complete forms or make verbal recommendations.

However, at Level II expectations change. We might reasonably ask somebody in a Level II role as to whether such incidences had occurred previously. We might ask what their views were with regard to the operating systems and procedures including whether they had reviewed them and what, if any, formal recommendations they had made with regard to improvement. We would expect such person in a Level II role to have collected data as well as implemented training procedures for operators.

In a Level III role we would ask the incumbent as to what analyses they have done with regard to all data with regard to operating procedures and practices and if they had identified from such data a systemic problem and reported formally with regard to the possible cause of that system problem.

In the Level IV role we would reasonably be asking questions about how this operating system was designed and modified in the light of other systems perhaps in the Social or Commercial Domains and what impact they thought the systems had on each other. We would ask what design work had they done to mitigate any negative interactive effects.

In a Level V role it would be reasonable to ask questions about second-order consequences; had they been identified, if not why not? What about the design of all of the systems throughout the organisation including how they all interact with each other? Is the technology used inherently stable? Thus we can consider complexity in the context of what is it reasonable to ask a person to manage and address. Expectations differ in kind and the nature as we worked through levels indicating the discontinuous nature of work.

We are not alone in using a discontinuous model. We reproduce a table from Levels of Abstraction in Logic and Human Interaction (refer to Box 6.2) which comprises various items.

Box 9.9 Appropriate Terminology

The appropriate terminology is to refer to ‘a person in a Level II (or III, or IV, and so on) role’. Never a ‘Level II person’ or a ‘Level V person’. That form of description is both insulting and demonstrates ignorance of the theory.

Conclusion

Thus, in summary, what we are saying is that as people work, each pathway they develop to achieve a goal is unique. There are, however, patterns common to the differing pathways that allow them to be sorted into discrete groups, or levels of work. The levels of work are discrete because the problem-solving methodologies employed by individuals up to their own personal maximum ability are discrete. Because we need to make goods or services, we formulate tasks, and each task will have a complexity for its resolution based on the degree of variance in the chaos that needs to be resolved for the task to be successfully completed. The mental processing ability of the person who identifies and performs the work of the task will determine the complexity of the work. If this complexity is equal to or greater than the inherent complexity of the task, the resolution will be successful.

At higher levels of the hierarchy, the pathways needed to formulate and to accomplish a task will be constructed in less certain conditions relative to tasks at lower levels. In general, as one moves from one level of work to the next, complexity increases in that:

• there are more variables to take into account;

• more of the variables are intangible;

• there is an increasing interaction of variables;

• results are further into the future;

• the links between cause and effect are extended in time, space and logic;

• apparently negative information (what is absent or does not occur) assumes more importance;

• the achievement of the objective may require the simultaneous ordering of variables from more than one knowledge field.

We must recognise that the patterns we have described are incomplete. Although it is tempting to want precise descriptions that would allow us to place everyone in their specific box, such an ability would be disastrous for human freedom and the ability to control one’s destiny. Of necessity, the descriptions of the patterns of complexity resolution apply to identified problems. They do not apply to the process of the thinking that identifies the problem and its potential solution while this is in progress. That would require describing what was going on inside somebody’s head while it was happening, the thought process itself. We are left with the need to draw inferences after the event. The investigative studies conducted by Isaac and O’Connor (1978) and others have produced data that shows a set of definite discontinuities, but even here the descriptors are at best a result of viewing through a glass darkly.

Instead we describe what are, we believe, transient patterns in the chaos, rather like clouds. Although no two clouds are alike, we can recognise the patterns of cumulus, cirrus, stratus or cumulo-nimbus clouds. The same is true of levels of work. No two people are alike, but with practise we can learn to recognise the patterns of complexity resolution they demonstrate. We can never be certain of our judgement, but we can do this well enough to select people for organisational roles more effectively than we can without this knowledge.

Essentially what we are providing is a language to describe differences probably already familiar to managers and others who have had the experience of working with people and assigning work. It does not take long to appreciate that some are more capable than others, and, what is more, they stay that way. This description is made easier when there is a language to describe the differences in complexity. The levels of work described are only a summary. These levels of work have been identified in several different research studies, and they have been tested in practice in business, governmental and voluntary associations.

Box 9.10 The Importance of a Person’s Worth

We cannot overemphasise the danger of equating MPA with the worth of a person. A person’s worth, in our view, is not calculated just by how ‘clever’ they are, and we must not confuse an organisational hierarchy of work with hierarchy of worth. People contribute much, much more than intellectual ability to life and society. (For the dangers of misuse, see Freedman, 2016.)

We also stress that we have talked about a meritocratic, managerial hierarchy based upon a hierarchy of complexity of work. Not all work has to be done in a managerial hierarchy; not all organisations are appropriately managerial hierarchies. Churches, universities and law firms/partnerships, for example, are properly organised in different ways, but all will need to understand the complexity of work to be done and who is able to do it. For examples of descriptions of work at different levels, please refer to the website www.maconsultancy.com.