Introduction: How We Managed People in the Past Will Not Work in the Future

Why Are We Still Using Management Methods Created During the Roman Empire?

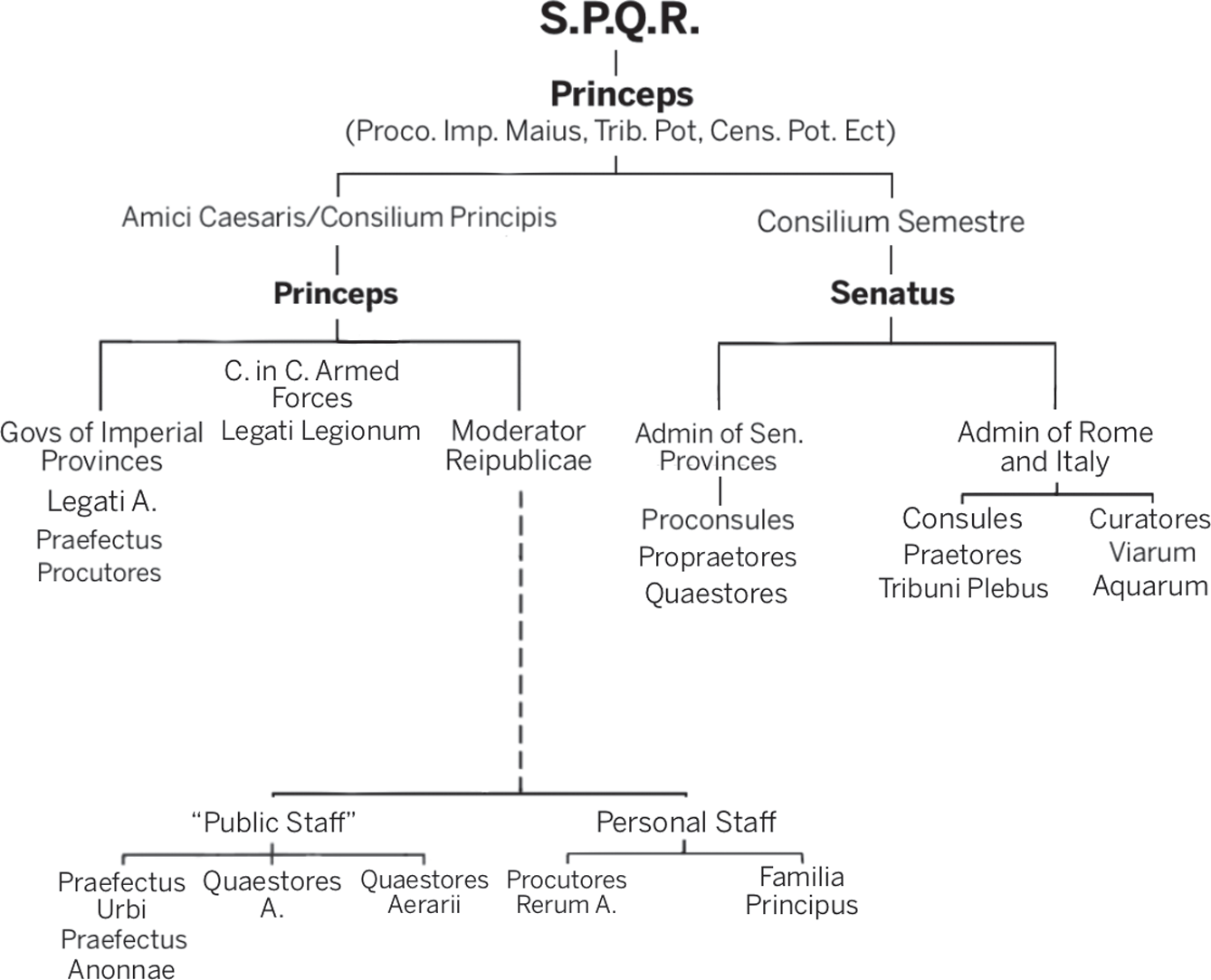

Many roads and buildings in Europe can be traced to the Roman Empire. In some cases, people literally walk on stones placed more than 2,000 years ago. Many other inventions created by the Romans also continue to shape our lives. Some endured because they still work, such as crop rotation in farming. Others are still used because they are familiar, even if they are not very effective. Hierarchical organization structures and the associated “org charts” used by companies belong in this category (see Figure I.1). Org charts categorize workforces based on how they are connected via higher level leadership positions. If the person in the role of “Governor of Imperial Provinces” on the left of Figure I.1 had an issue with the “Administrator of Rome and Italy” on the right they would first go to their leader the “Amici Caesaris,” who would talk to the “Proco. Imp. Maius,” who would then communicate to the “Consilium Semestre,” who would finally tell the “Admin of Rome and Italy.” This top-down method for workforce management has been familiar to leaders since the Roman Empire, but it has significant limitations when applied to the modern workforce.

Hierarchical organizational structures were created to manage workforces during a time when work was largely defined by geography. Prior to the 21st century, where people physically lived heavily influenced the work they did and whom they worked with. Team members all worked in the same building with their immediate leaders. Org charts usually mirrored how the workforce was structured geographically.

The rise of the internet economy has created a split among people's location, roles, and work relationships. Teams are no longer constrained by geography. It is common for people to work in one city, report to a manager in another city, and collaborate with people across the world. Org charts might accurately reflect how a company reports financial numbers, but they contain little information about the roles, social interactions, and relationships that drive profit and loss. Where an employee is placed on an org chart, it may tell little about what they do or who they work with. The continued use of org charts also reflects a top-down leadership style that is antithetical to the cross-functional nature of most modern organizations. It implies that decision-making authority resides in roles higher up the chart, which disempowers frontline employees to act quickly. Because org charts often provide little insight into what people actually do or how they work together, using org charts to guide workforce decisions can also result in inadvertently firing the wrong people and disrupting team relationships that are critical to a company's performance. I have known multiple companies that let employees go based on their positions on an org chart, only to discover these people were doing work that was critical to the company's performance. In several cases, they had to rehire the people as contractors at much higher pay rates with much lower levels of organizational commitment.

FIGURE I.1 Roman hierarchical organizational leadership structure.1

Source: The Government of the Roman Empire Under early Principate. (n.d.). [Gif]. Fordham University. https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/ancient/spqr-under-augustus.gif

Innovations in technology have created tools that are far superior to org charts for capturing information about the employee roles, skills, and relationships that make a company function.2 Relatively few companies have adopted these tools largely because it would require leaders to change how they make decisions. At some point, leaders will stop clinging to their love of org charts. When that day comes, employees will rejoice in seeing org charts jettisoned to join bronze swords, lead plumbing, and other things from the Romans that were once useful but are now at best inefficient and at worst harmful.

The purpose of this book is to help organizations build workforces for a future that is very different from the past. It discusses how the twin “talent tectonic” forces of digitalization and demographics are changing the nature and purpose of work. It explains the psychology of employee experience and why it is critical to building adaptable organizations that can thrive in a world of accelerating change and frequent skill shortages. It discusses how to integrate business strategy, psychology, and technology to create more nimble companies. And it explains why we must move beyond ineffective workforce management methods based on outdated technology such as hierarchical org charts.

This book discusses the future, but its focus is on the present, identifying things companies can do now to attract talent and create resilient organizations. It also talks about the one thing about work that is not changing: the psychology of the people who work in organizations and how employee experience influences their engagement, performance, and adaptability. This book looks at these topics from the perspective of an industrial-organizational psychologist who has helped thousands of companies around the world use technology to build effective workforces. Few people have viewed the future of work from this particular angle. The book is based on engagements with organizations spanning virtually every industry.i It also incorporates a range of research from industrial-organizational psychology, management science, socioeconomics, and related fields. The book is a product of extensive experience working at the intersection of people, technology, and work. My goal as an author is to draw on this experience to share business insights you may not have considered and practical psychological knowledge you may not have encountered. The book includes fairly extensive citations if you wish to dive more deeply into the science and data underlying many of these concepts and observations.

The book provides guidance on how to attract, retain, develop, engage, and manage people for a new world of work, keeping in mind there is no one best way to manage workforces. My career involves working with companies over multiple years and I have seen how workforce management techniques play out over time. Theoretically well-designed processes often fail in application. Methods that work in one company fail in others, and methods that worked in one company at one time may not work later based on changing technologies, leadership characteristics, and company resources. It is critical to determine what solutions are appropriate for an organization given its unique culture, business needs, and resource constraints. Each chapter in the book ends with a set of questions to discuss with company leaders, managers, and/or employees to determine what makes sense for the organizations you work with. A goal of this book is to help you understand why these questions matter, when they are important to discuss, and what to consider when answering them.

Content Overview

The book is meant to be read from front to back. However, each chapter stands on its own for readers who are interested in specific topics. The first three chapters address changes reshaping work and workforce management. The remaining chapters provide guidance on how to respond to these changes. The content of the chapters is summarized next.

Forces Reshaping Work and Workforces (Chapter 1). The phrase talent tectonics describes fundamental shifts reshaping work and organizations. The two biggest shifts are the accelerating pace of change caused by digitalization and the reshaping of labor markets caused by demographic changes in birth rates and life spans.

- Digitalization. As technological innovation expands into every facet of life it increases the speed of change. This affects multiple aspects of corporate life including company survival. The life span of companies is growing shorter while the acquisition rate of companies has steadily increased.3 Companies are restructuring faster than ever before. Industries are being altered with changes in one industry creating changes in another. For example, the shift to electric cars is transforming the automotive industry but also has massive implications for the energy, transportation, mining, oil and gas, and manufacturing industries.4 This level of change is also playing out at the level of individual jobs. Automation is eliminating long-standing tasks while creating new types of work.5 Even enduring professions such as land surveying, which dates back to the ancient Egyptians, are being completely altered by inventions such as satellite and drone technology. Whatever a company or job looks like now, it will almost certainly be different in three years.

- Demographics. People are living longer and having fewer children, and not just by a small amount. The life expectancy in the US has increased by 38 years since 1910.6 The generation of workers currently entering the economy can expect to live about one-third longer than their great-grandparents. At the same time, the global birth rate has declined by 51% since 1950.7 In many countries more people are leaving the labor market than entering it.8 Barring catastrophic events such as wars, this has never happened in modern history. It is creating growing labor shortages and redefining job markets. Companies are already struggling to find skilled employees and filling job roles is predicted to become even more challenging.9

Similar to how movement of geological tectonic plates drives changes on the surface of the earth, these two talent tectonic shifts are creating visible changes in the nature of organizations and work. Companies can treat these shifts as threats to be managed or opportunities to be leveraged, but either way they must adapt to survive. This starts with understanding how these technological and socioeconomic forces are changing the nature of work, jobs, organizations, and careers.

Employee Experience and Workforce Adaptability (Chapter 2). The world of work is radically changing, with one critical exception: organizations will always employ people, and the fundamental psychology of people is relatively constant.10 Despite popular assertions that generations are radically different from one another, studies dating back to the 1920s show that the nature of what people want from work does not change much over time.11 The things that make us happy, engaged, and healthy at work are rooted in human psychological attributes that do not evolve as quickly as technology and societies. What does change is the ability of people to demand better employee experiences at work. To illustrate this concept, consider two historic talent tectonic shifts from the 20th century: the workers' rights movement and the women's suffrage movement.

- Coal miners in the late 19th century did not know what black lung disease was, but they did know that working in the mines was killing them prematurely.12 Coal companies did not pay much attention to how miners felt about their safety given the social values and labor markets at the time. Miners were unable to demand change lest they lose their jobs and the ability to provide for their families. Miners did not get protection for black lung disease until the workers' rights movements of the early 20th century changed social values regarding the obligation of companies to protect the health and safety of employees. The workers' rights movement did not change miners' desire for a better work environment. What changed was their ability to demand healthier working conditions.

- In the early 20th century, social attitudes toward educating women radically shifted due to the women's suffrage movement.13 This led to an increase in women achieving college degrees throughout the 20th century. The rise in women's education led to large numbers of women in the 1960s and 1970s launching careers in professions that had historically been limited to men. These women faced openly sexist behavior and blatant sexual discrimination in pay and promotions. Working women in the 1970s did not like this discrimination but many did not feel empowered to overtly challenge it. By the beginning of the 21st century more women were graduating from college than men in many countries. As more women entered the workforce, social attitudes continued to shift toward gender equity, and overt sexism and blatant discrimination were no longer tolerated. We have a lot of work to do to achieve full gender equity, but this is not a function of changing what working women want. Working women always wanted to be treated fairly and respectfully. What has and continues to change is their ability to demand they be treated as equals.ii

These examples illustrate how past talent tectonic forces have driven companies to create better working conditions and employee experiences. Chapter 2 explains why improving how employees experience work is critical to responding to the current talent tectonic forces of digitalization and demographics. It also discusses the different types of employee experiences that affect work, why they matter, and how they are shaped by employee expectations, perceptions, and interpretations.

Work Technology and Organizational Agility (Chapter 3). Work technology refers to solutions designed to build and manage workforces so they deliver the goals of the business. At the broadest level, this technology focuses on doing five basic things: enabling people decisions such as hiring or compensation, creating work communities and teams, supporting employee development, ensuring security and compliance, and reducing time needed to complete administrative actions. Chapter 3 explains the role that different types of work technology play in creating more agile organizations. It focuses particularly on the value technology provides by enabling large companies to act more like small entrepreneurial organizations.

Perennial Workforce Challenges (Chapters 4 through 8). Chapters 4 through 8 examine the future of work from the perspective of seven perennial workforce challenges (see Table I.1). These challenges are called perennial because companies always have to address them, and they never go away. They include designing organizations, filling roles, ensuring employees have the skills to perform their work, engaging employees to achieve company goals, increasing efficiency of work, complying with laws and regulations, and building culturally effective companies. These challenges can also be viewed from an employee perspective such as finding career opportunities, learning new skills, accomplishing career goals, achieving success, and making effective use of time.

TABLE I.1 Perennial Workforce Challenges

| Challenge | Company Perspective | Employee Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| What companies must do: perennial challenges to building and managing workforces | ||

| Designing organizations | How will we structure roles and pay people? | What career opportunities are in this company? |

| Filling positions | How can we get the right people into the right roles? | How can I move into new roles? |

| Developing capabilities | How can we build people's skills and abilities so they can effectively perform their roles? | How can I achieve my future career goals? |

| Engaging performance | How can we motivate and retain people to execute the company's strategy? | How can I get fulfillment from my current work? |

| How companies do it: perennial challenges to creating highly effective workforces | ||

| Increasing efficiency | Are we maximizing the time of our employees and the money invested in our workforce? | Is it easy to get things done? |

| Ensuring compliance | Are we fulfilling our legal and ethical obligations? | Am I being treated fairly? |

| Building culture | Are we supporting our core values? | Does the company align with my beliefs? |

The seven perennial workforce challenges provide a sense of order in the fast-changing world of work. I like to compare them to the perennial challenges associated with throwing a great party because both have to do with creating positive experiences. For organizations it is about creating experiences that inspire employees to work collaboratively to achieve company goals. For parties, it is creating an environment that inspires guests to have fun. A perennial challenge to throwing a good party is figuring out what music will inspire people to dance. In the 1920s people solved this challenge by playing ragtime music on a Victrola. Now we download a playlist of current hits from the web. Similarly, people's expectations about work and the technology they expect to use in organizations has changed since the 1920s. But the basic challenges to building workforces and throwing parties have not changed because they are about psychological truths. Employees want to be appreciated at work and people want to dance at parties. What changes are the nature of people's expectations when it comes to doing these things and the available technology to meet these expectations. The perennial workforce challenges never change, but the relative importance of each challenge changes in response to company growth, business market conditions, and shifting labor markets. The methods used to address the challenges also change due to technological innovation. For example, the internet profoundly altered how companies fill roles, and remote work technology is radically changing how companies design organizations.

Chapters 4 to 8 examine these challenges from the perspective of their impact on employee experience and how technology is transforming the methods companies use to address them.

- Designing Organizations to Provide Positive Employee Experiences (Chapter 4) is about determining what jobs define the company, where they are located and how they are organized and compensated. In the past, companies approached organizational design mainly as a financial activity with employee experience an afterthought. More attention needs to be placed on the employee experience, recognizing that people do not join companies to fill department headcount requirements. They join because something about the organization appeals to them. The top issue on employees' minds when considering a job or going through a corporate restructuring is not “how will this help the company's financial portfolio.” It is “how will this affect my job experience, career opportunities and work relationships?”

- Filling Positions and the Experience of Moving into New Roles (Chapter 5) is about finding and hiring people to perform different functions including transferring people internally based on business needs and career interests. In the past, companies assumed they could find talent when they needed it. This is no longer the case for many jobs. Companies must look at hiring from an employee experience perspective, recognizing that people do not want to be qualified, selected, and onboarded. They want to discover opportunities, learn about roles, be welcomed into organizations, and develop new careers. This means filling roles based on what candidates want and not just what companies need.

- Developing Capabilities and the Employee Experience of Learning (Chapter 6) is about providing people with knowledge and skills to perform current work and take on future responsibilities. In the past, development programs focused on making incremental improvements to employee's existing capabilities through training. This approach worked when careers were more stable and linear. This view of career growth no longer makes sense in many industries.14 It is not enough to train employees to be better at their current job if their current job is likely to radically change or disappear due to automation. Companies need a new approach that views development as enabling people to do things that are much different from what they did in the past.

- Creating Engagement and Employee Experiences That Inspire Successful Performance (Chapter 7) is about guiding, inspiring, supporting, and retaining employees to achieve the goals of the company. Companies must put considerable effort into engaging employees in a high-pressure world where people can easily change jobs if they are not fully supported in their roles. Another topic discussed in this chapter is team performance dynamics, recognizing that the performance of the people we work with has a major impact on our own experience of work, particularly when we are under pressure.

- Increasing Efficiency, Ensuring Compliance and Security, and Building Culture (Chapter 8) is about how companies can address the first four challenges in ways that optimize the time and money spent on workforce management activities; comply with employment regulations, laws, and contracts; address security and compliance risks; and support cultural values related to health and well-being, diversity and inclusion, and environmental sustainability. This chapter also discusses the importance of hybrid/remote work cultures. People do not want to work for companies that do not respect their time, privacy, safety, rights, and values. Nor do they want to work for companies that force them to relocate or commute to an office if they feel it is unnecessary to doing their job.

An important difference between the seven perennial challenges and the more traditional process view of human resources (HR) that focuses on things such as recruiting, training, or performance management is their inter-complementary nature. As the nature of work changes, the distinction between traditional HR processes is disappearing. For example, the design of a company's organization influences how it fills job roles and develops employee capabilities. Training is one method to develop employees, but staffing can be a more powerful tool for development if used in the right way. One of the most effective ways to get someone to learn how to do something is to put them in a job that requires knowing how to do it and then help them develop the capabilities and skills they need to succeed. An overarching theme in the future of work is moving away from narrow process-oriented views of workforce management toward methods that use a range of techniques to address broad workforce challenges.

Using Employee Data to Guide Business Decisions (Chapter 9). Companies are gaining access to unprecedented levels of data about the workforce. Companies have much to gain from leveraging this data to increase workforce efficiency, ensure compliance and better understand, influence, and predict employee behavior. Yet many companies make little use of this information or use it ineffectively. Benefitting from data requires developing methods to collect and analyze workforce data in an efficient, sustainable manner, giving the data meaning by framing them in the context of business problems, and managing concerns about data privacy and security.

Changing Employee Experience (Chapter 10). Talent tectonic shifts are forcing companies to solve old challenges in new ways. It can be difficult to get leaders to realize that the way the company solved perennial challenges in the past will not work now. Companies often persist in doing things the way they have always been done simply because they have always done it that way, using technology to incrementally improve existing work methods as opposed to making large-scale changes to improve employee experience. This chapter discusses common barriers to changing work practices including why leaders dislike changes, why managers struggle to support changes, and why employees resist them.

Employee Experience and the External Environment (Chapter 11). The experiences that people have at work are influenced by the experiences they have outside of work. This chapter discusses societal issues that shape and often constrain the ability to reimagine the nature of employee experience, noting how many of our current views about work are still rooted in social norms and work technology constraints from the 20th century.

Where Do We Go from Here? (Chapter 12). The book concludes with general thoughts about how work will evolve over the coming years and the role companies play in shaping the future of employee experience.

The Vocabulary Used in This Book

When it comes to talking about work, words matter. For example, I know companies who refer to employees as partners, associates, champions, athletes, team members, cast members, or crew members and are adamant that their employees be referred to by these names. There are valid reasons why companies rename or redefine common terms. But it creates confusion when working across companies. For this reason, here are definitions for some commonly used terms in this book.

- Organization: a group of people who collaborate to achieve common goals by sharing common resources. The terms company and organization are used interchangeably, though not all organizations are commercial companies (e.g., government or nonprofit organizations).

- Employee: a person who receives financial compensation from an organization for work they perform on the organization's behalf. This includes contract workers as well as direct employees. The terms employees, workers, and people are used fairly interchangeably.

- Candidate: a person who may have the potential to become an employee. An applicant is a candidate who has expressed interest in a certain job role.

- Manager: a person who has responsibility for guiding the work of employees. Many managers oversee staffing and compensation decisions, but not all do.

- Leader: a person responsible for setting the strategic direction of a company or group. Most leaders are also managers.

- Digitalization: the application of technology in a way that transforms, augments, automates, or otherwise noticeably changes some aspect of work and life.

- Rating: assessing and placing people in different categories based on qualifications, potential, performance, or some other attribute relevant to work. Rating requires categorization but it does not require using numerical labels, ranking people against each other, or evaluating people as better or worse individuals.

- Talent: the capabilities employees possess that enable them to achieve business-related objectives including knowledge, skills, abilities, values, motives, and attitudes. Skilled employees are also sometimes referred to as talent.

- Workforce: used to refer to all the employees working for a company including senior leaders and contractors, as well as to refer to the labor force available in a broader society.

- Workforce management: methods, actions, and processes focused on helping organizations create effective workforces. Other terms used for this include human resources, human capital management, or human experience management.

I strive to use these and other words in a consistent manner throughout the book. I also try to avoid marketing jargon, trendy terms, and other phrases that often sound good but mean little.

Notes

- i Most stories and examples in this book are based on companies I have worked with over my career. I do not share names of companies for several reasons. First, not all the stories are positive. Second, I do not want people to evaluate an example based on the name of the company that did it. Just because a company has a strong public brand does not mean it has good workforce management methods. The company Enron was widely admired for years despite using abhorrent workforce management methods to create fraudulent financial results. Conversely many great workforce management methods are found in privately held organizations few people have heard of. Company names are not what matters. What matters is what we can learn from company practices.

- ii This example reflects stories my mother shared as a professional woman who founded a company in 1972. Working women of her generation demonstrated amazing strength and determination overcoming sexist attitudes about the roles, capabilities, and value of women in the workplace.