| 2 |

Corporate Culture: The Alien’s Garden

If you inquire what the people are like here, I must answer, “the same as everywhere.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Effective teaming requires, and helps create, a friendly environment or corporate culture. The two virtues go hand in hand. Teaming cannot prosper in rigidly structured, command/obedience, top-down, fear-inducing hierarchical cultures. Virtually all organization personnel must change—indeed, literally reverse their entrenched historical character—if teaming is to prosper. But, changing such deeply ingrained habitual attitudes and behaviors requires persistent and total dedication, approaching almost heroic proportions.

Habitual behavior is addictive behavior. Changing embedded corporate culture means breaking addictions, a painful journey fraught with pitfalls, risks, doubts, and uncertainty. We shall see (in this and the next chapter) that psychological readiness to suffer the pain of withdrawal from habitual addictive behaviors is the single most critical step, which each individual employee must take, before culture can change. The old ways, although imperfect, are known ways, offering perceived security, comfort, and predictability. Change causes some people to feel a profound sense of personal loss (not unlike loss of a loved one) and accompanying grief. We shall examine how working through that grief determines each individual employee’s willingness and ability to adapt to, and adopt, change. The pace of total corporate cultural change depends, in large measure, upon how fast and completely those individuals work through and come to terms with their sense of loss and grief (see Appendix III).

Those looking for easy answers should consider keeping things the way they are, and forget about teaming. The good news is, however, that well-planned and sustained change processes reap early and increasing results that encourage and reinforce those willing and able to persevere. The battle never ends, but its uphill character does eventually reverse.

This chapter probes into the character of corporate culture and offers insights about how it might be changed. The following chapter topics construct a mechanics of corporate cultural change aimed at facilitating management transformation and effective teaming:

Relating Culture to Management

Relating Culture to Management Culture and Cultural Change as Abstract Ideas and as Operational Entities

Culture and Cultural Change as Abstract Ideas and as Operational Entities Definitions of Management, Management Transformation, Culture, and Cultural Change

Definitions of Management, Management Transformation, Culture, and Cultural Change The Key to Operationalizing the Concept of Culture

The Key to Operationalizing the Concept of Culture The Logic of Management Transformation

The Logic of Management Transformation Organic versus Mechanical Systems

Organic versus Mechanical Systems A Pincer Envelopment Strategy for Cultural and Management Change

A Pincer Envelopment Strategy for Cultural and Management Change Pincer Strategy Components

Pincer Strategy Components Explaining the Levels of Analysis

Explaining the Levels of Analysis Explaining the Disciplines of Knowledge

Explaining the Disciplines of Knowledge Resistance to Change: “There Be Devils!”

Resistance to Change: “There Be Devils!”

RELATING CULTURE TO MANAGEMENT

Imagine that culture is to a corporation what soil and environment are to a garden. Sterile soil and inhospitable environments do not nurture healthy plants. Soil must be nourished and the environment protected. Soil and environment act together in complex, interdependent, and integrated patterns that are compounded of more than the simple arithmetic sum of their constituent elements.

Smart gardeners always dream of better crops and forever look for better ways to enrich the soil and environment in which to grow them. They find joy in, and are uplifted by, nature and the privilege of being allowed to participate in a universe-centered, rather than a self-centered, enterprise.

The connection between the gardener metaphor and the dynamics of corporate management transformation is quite direct. This book makes that association and offers a design for initiating and sustaining desired changes in corporate culture (the corporate soil, climate, and environment) leading to management transformation (the new improved corporate plant).

CULTURE AND CULTURAL CHANGE AS ABSTRACT IDEAS AND OPERATIONAL ENTITIES

The assumption that cultural change is at the heart of quality management and project management has become one of the mantras chanted in management literature, seminars, classrooms, conferences, and symposia. The ideas of corporate culture and cultural change are well appreciated and accepted. If, however, quality management and project management practitioners are ever to act with consistent theoretical rigor to predictably change corporate culture, they must first define it as more than an abstract idea. They must define the term culture operationally—that is, in concrete, physically observable change-process terms that are analogous to the abstract idea and can be measured, manipulated (or operated upon), and evaluated.

Returning to the gardening metaphor, a creature living in outer space might accept the idea of the word soil but would hardly be able to appreciate or comprehend it in operational terms. Therefore, the alien would be ill prepared to understand, experience, or conduct the mechanics of gardening. Like our terrestrial friend, we have come to appreciate the ideas of corporate culture and cultural change but have much to learn about their operational mechanics.

This chapter offers an operational definition of culture and a consequent mechanics for conducting and evaluating its teaming-friendly change. The mechanics relies on a rather simple logic, backed by a set of philosophical assumptions concerning human relationships and from successful applications in public, private, civilian, and military sectors.

DEFINITIONS OF MANAGEMENT, MANAGEMENT TRANSFORMATION, CULTURE, AND CULTURAL CHANGE

If the ultimate purpose of corporate cultural change is to transform management, then it is necessary to define these terms, in ends-to-means order—that is, management first, then culture. Each definition is worded to help us both conceptualize the abstract terms and learn how to empirically operate upon them.

Management, defined in Chapter 1 (also see Shuster’s Laws (S/L) Definition #1, Appendix I), is “the act of determining the way we do the things we do.”

Management, defined in Chapter 1 (also see Shuster’s Laws (S/L) Definition #1, Appendix I), is “the act of determining the way we do the things we do.” Management transformation concerns the way we improve management.

Management transformation concerns the way we improve management. Culture is the holistic summation of individual community members’ habitual attitudes and behaviors.

Culture is the holistic summation of individual community members’ habitual attitudes and behaviors. Cultural change is cultural metamorphosis or mutation, accomplished through purposeful alteration of individual habitual attitudes and behavior.

Cultural change is cultural metamorphosis or mutation, accomplished through purposeful alteration of individual habitual attitudes and behavior.

Management, as discussed in Chapter 1, focuses less on the things that people are doing technologically and more on the processes (conversions) through which they are doing them. Purposeful cultural change cannot occur, therefore, without visible, persistent, dedicated, and driving commitment.

Management transformation pertains to improving management, which means continuously critiquing and changing the way we do the things we do (S/L #21, Appendix I). Feeling comfortable with this sense of chaos, disturbance, uncertainty, risk, turbulence, loss of comfort zones, and movement into unknown realms is crucial for people if they are to appreciate and accept their transforming journey. For those inclined toward the status quo and grieving for the loss of “things the way they were,” this prospect can be quite discomfiting.

Those who fear projecting themselves into a future beyond experience must (as discussed in Chapter 3) become psychologically ready to suffer the pain of withdrawal from their addictive habitual ways, question their own preconceptions, and be comfortable in a turbulent environment (S/L #3, Appendix I).

They must learn to treat experience as a conditional data point (defined as one factor among many factors), but not as an absolute and inviolate rule for defining or circumscribing future possibilities (S/L #23, #25, #27, Appendix I). Nonetheless, their painful sense of loss over things as they were is honestly felt, and its effects can be crippling if it either goes unattended, is ridiculed by managers and peers, or is absent as a variable in the theory that guides change.

Numerous conceptual and abstract definitions of culture populate the social sciences, offering little in the way of measurable rigor. Although highly abstract, they provide important insights into the effect of culture on management.

Typical conceptual definitions include the following:

Culture is the way of living developed and transmitted by a group of human beings, consciously or unconsciously, to subsequent generations.…[It is] ideas, habits, attitudes, customs, and traditions.…[It is] overt and covert coping ways of mechanisms that make a people unique in their adaptation to their environment and its changing conditions. (Harris and Moran 1990, 134)

Culture is the integrated pattern of human behavior that includes thought, speech, action, and artifacts and depends on mans’ capacity for learning and transmitting knowledge to succeeding generations. (Deal and Kennedy 1982, 4)

Insights derived from such definitions include, first, the refreshing ideas of integration, system, pattern, and holism. Western scientific thinking has driven too many of us to extreme reductionism—i.e., the idea that if we break complex systems into separate and isolated parts, then all we have to do is tie the individual items together again, and we shall understand the whole. How often, for instance, do we hear statements such as, “You do your part, I’ll do my part. We’ll keep out of each other’s way, and things will be just fine.” Or, “It worked on the test bench; why is it failing when we put it into the system?” Fortunately, systems analysis and systems integration are becoming staples of the physical, natural, and behavioral sciences.

Consistent with this integrating cultural perspective, W. Edwards Deming asserts the holistic prescription for optimizing the system as the cornerstone of his management philosophy (see Chapter 3). Stephen Covey elevates interdependence over independence in human relationships. Psychologist M. Scott Peck recommends that inclusive mutually bonding communities replace their exclusive restrictive counterparts. I combine their perspectives in my principle of optimizing the organic community (described later in this chapter) as the foundation supporting teaming-friendly cultural and management transformation.

These conceptual definitions of culture properly disabuse us of this reductionist fallacy. They suggest the idea of holistic culture, i.e., a complex web of bound-up and survival interdependent elements.

Second, these definitions effectively communicate appreciation of the learning environment that culture provides for teaching and socializing new generations. They target the social capacity for transmitting knowledge to succeeding generations.

What these typical conceptual definitions of culture do not do, however, is provide a basis for operationalizing that concept in the sense that management transformation requires. The terms in the definitions are so loosely constructed, broad in scope, group focused, abstract, and boundless that they make comparison and measurement virtually impossible.

THE KEY TO OPERATIONALIZING THE CONCEPT OF CULTURE

The key to overcoming this definitional weakness, and finding a valid and reliable operational definition of culture, grew out of a 1960s revolution in strategic thinking and group theory. It centered upon a new way of thinking about individual attitudes and behavior, as modified by group association.

Culture implies the idea of group—that is, a defining set of relationships and expectations shared by two or more individuals that sets them off from other people. Although almost everyone knows that a group is a concept, and not a living person, some of us have allowed ourselves to reason with the hidden but implied assumption that groups are behaviorally the same as individuals. That seemingly innocent slip in exactness too often results in misleading conclusions. For instance, we sometimes pigeonhole people by political, economic, social, sexual, ethnic, racial, national, religious, and other preconceived categories. Then we presume to act as if we understand the qualities of those individuals according to the categories into which we have arbitrarily placed them.

How often, for example, do we hear someone say something to the effect that “Joe is a Republican, therefore, he thinks that.…” And, political pundits think nothing of declaring that “the administration [or the White House] stated today that its policy is.…,” taking no discomfort in attributing to the executive branch of the federal government (a conceptual group) the same qualities of existence, thought, and speech normally reserved for living individuals. Our individuality is too often submerged into the particular box (subgroup) on the organizational chart into which we have been placed, where we acquire the habit of speaking freely about “this division’s” conformity to “company” policy. We too easily forget that only people can make and respond to policies. One negative result of this viewpoint is the tendency to avoid individual accountability for action. When the organization is accountable, no one person is accountable.

The breakthrough in group theory that serves our purpose came when its practitioners acknowledged that trying to operationally define the thinking and behavior of a group—an entity that exists only as a concept—required recognition of the distinction between a physically existing individual and a conceptual collection of individuals. Their new underlying axiom of group theory (S/L #4, Appendix I) became:

Groups do not act; people do!

Simple truths simply stated are very powerful. What this fundamental principle asserts is that the way to behaviorally comprehend, predict, and control group behavior is to approach it through analysis of the living, acting individuals of which a group is composed. Individual attitudes and behavior can be observed, measured, and changed. Group behavior—even the uniform swarming of bees, flocking of geese, or schooling of fish—can only be observed by seeing individual creatures within the context of their collective action. In other words, the sense of pattern that we perceptually impose on the swarm, flock, or school obscures the fact that we are actually physically sensing the actions of individual animals who happen to be acting together. Therefore, the critical modifier to the proposition that only living individuals can act is that the pattern of their collective behavior is more than the simple arithmetic sum of their individual behaviors. It includes the invisible interrelationships bonding them together.

The lesson to be learned here is that individual members of a group do not act independently, as they do when they are alone. They act interdependently, and, the complex, ever-changing mixtures of factors defining the character of their association are as much a result of the interwoven relationships existing between the people as they are a part of the personal character of each individual. Stated again, interrelationships make the whole more than the simple arithmetic sum of its parts.

There exist, fortunately, many reliable psychological instruments available to measure, classify, and evaluate individual attitudes and behavior. The chances are that each person reading this book has taken intelligence, interest, attitude, and psychomotor batteries during her lifetime—and therein lies the secret to operationalizing cultural change. First, measure individual attitudes and behavior and, second, ascertain how the holistic pattern of interdependent collective forces modifies that behavior within group associations; i.e., compare how they operate alone and together. Using this methodology, the abstract concept of culture can be restated and measured in concrete empirical terms.

THE LOGIC OF MANAGEMENT TRANSFORMATION

Changing corporate culture to transform management requires a logically constructed plan, which includes the following propositions:

The ultimately desired end of management transformation is to build a vibrant organization that simultaneously becomes a leader in the new globalized competitive market, prepares for continuing leadership into the near and far future, and provides a healthy, self-actualizing, and fulfilling environment for every individual within its employ. The key to this haven is achieving and maintaining total customer satisfaction.

The ultimately desired end of management transformation is to build a vibrant organization that simultaneously becomes a leader in the new globalized competitive market, prepares for continuing leadership into the near and far future, and provides a healthy, self-actualizing, and fulfilling environment for every individual within its employ. The key to this haven is achieving and maintaining total customer satisfaction. The secret to totally satisfying customers is to always give them more than they expect.

The secret to totally satisfying customers is to always give them more than they expect. The secret to giving them more than they expect is to practice empathic management, meaning viewing things from your customers’ perspectives and enabling them to totally satisfy their customers (S/L Definition #6, Appendix I).

The secret to giving them more than they expect is to practice empathic management, meaning viewing things from your customers’ perspectives and enabling them to totally satisfy their customers (S/L Definition #6, Appendix I). The surest way to totally satisfy external customers and practice empathic management is to totally satisfy internal customers (all company personnel).

The surest way to totally satisfy external customers and practice empathic management is to totally satisfy internal customers (all company personnel). The surest way to totally satisfy internal customers is to unify the organic community.

The surest way to totally satisfy internal customers is to unify the organic community. The surest way to unify the organic community is to create, nurture, and sustain an enabling environment, in which people feel safe enough to lower their protective shields and make themselves vulnerable, and free enough to express (and act in accordance with) their own ideas, rather than simply reacting to external management directives.

The surest way to unify the organic community is to create, nurture, and sustain an enabling environment, in which people feel safe enough to lower their protective shields and make themselves vulnerable, and free enough to express (and act in accordance with) their own ideas, rather than simply reacting to external management directives. An enabling environment (S/L Definition #4, Appendix I):

An enabling environment (S/L Definition #4, Appendix I):

Liberates intellect.

Liberates intellect. Generates consensus.

Generates consensus. Empowers people to act in accordance with their own ideas.

Empowers people to act in accordance with their own ideas. Eliminates fear of failure (failure acceptance prevents disasters).

Eliminates fear of failure (failure acceptance prevents disasters). Loves, nurtures, and embraces risk, change, and failure.

Loves, nurtures, and embraces risk, change, and failure. Celebrates diversity.

Celebrates diversity. Cements unity.

Cements unity. Inspires joy.

Inspires joy. Ensures fulfillment.

Ensures fulfillment. Recognizes dignity.

Recognizes dignity.

The surest way to create an enabling environment is to devise a strategy for changing the corporate culture. This requires universal participation.

The surest way to create an enabling environment is to devise a strategy for changing the corporate culture. This requires universal participation. A fruitful way to change corporate culture is to base the process on 1) principles of addiction withdrawal, and 2) working through the grief caused by the profound sense of loss accompanying change.

A fruitful way to change corporate culture is to base the process on 1) principles of addiction withdrawal, and 2) working through the grief caused by the profound sense of loss accompanying change.

ORGANIC VERSUS MECHANICAL SYSTEMS

Organic Community

The concept of the organic community grows out of literature in the behavioral sciences and philosophy. Three authors who have had significant impact on my thinking are psychoanalyst Peck, chaos theorist James Gleick, and social dissenter Saul D. Alinsky. Also, as noted earlier, transforming management consultant Deming stressed the idea that the single most important requirement for successful management change is the associated idea of optimizing the management system.

Organic systems are best viewed as biological entities that display the behavioral qualities of a living organism. The survival of a body’s parts and the whole body are inextricably bound up in each other. They cannot be separated; they are totally survival interdependent. Ensuring, for example, the health of one’s stomach to the total exclusion of caring for the rest of the body is an exercise in futility. A sick spleen and a corrupted liver will eventually cause the stomach to suffer. To paraphrase Abraham Lincoln, a body divided against itself will not survive.

Therefore, in an organic system, it is both difficult and unwise to view the parts and the whole separately. They must be seen as merged into a symbiotic oneness, each contributing a unique quality that ensures the survival of all. They are, in effect, survival interdependent.

Mechanical Systems

These systems, quite oppositely, are composed of parts that work together but are not survival interdependent. For example, a broken trigger housing might render a rifle inoperable but does not threaten the health or survival of the stock or barrel. Simply replacing the housing repairs the rifle; its parts are survival independent.

Organizations that encourage people to focus their interests, perspective, duties, and accountabilities exclusively within their particular boxes on the organization chart tend to view the company as a mechanical system. This parochialism creates the all-too-familiar barriers to communication so evident in bureaucracies. Transformed organizations reverse this tendency.

People in changed cultures learn to view their organizations and their parts in them as organic systems. In this environment, the interests of the parts are indistinct from the interests of the whole. One’s personal interests are defined within the context of the general interest, and the general interest is always circumscribed within the context of individual interests. This idea is not utopian. Anthropologists have recorded long-surviving societies so organized; for example, the ancient city-state of Athens rested on this premise. Communities form in this way in the face of natural disasters, and organizations throughout the United States are transforming in just this manner under the banner of the quality revolution.

Members of organic communities soon learn to admire differences in people, instead of fearing them. They learn to be accepting and inclusive with others, rather than rejecting and exclusive. Their sense of personal wholeness grows, nurtured by their satisfied need to associate with others, and by others accepting their need for independent liberty of thought and action. Expectations and accountability are given and taken in consensual mutual accord. You will see in Chapter 6 how such mutuality and consensus are captured and mobilized through specialized voting procedures.

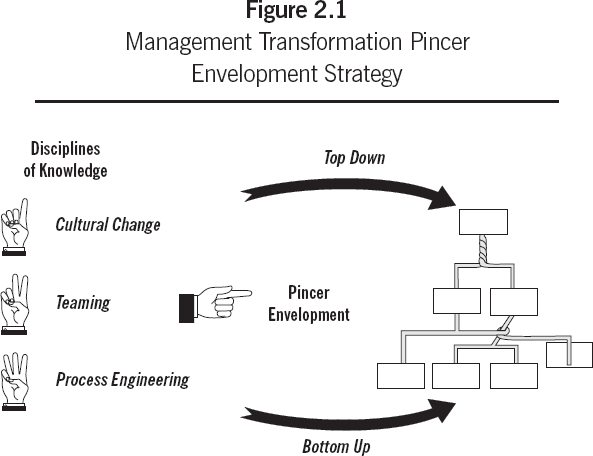

A PINCER ENVELOPMENT STRATEGY FOR CULTURAL AND MANAGEMENT CHANGE

Changing mechanical into organic communities, and thereby transforming corporate cultures and management systems, requires a grand strategy. I developed a two-pronged pincer envelopment strategy that invades and engulfs the target organization in change, and I have successfully employed it in public, private, military, and civilian contexts. The invasion plan involves simultaneously approaching selected people at every corporate vertical level and every horizontal unit. The aims are to:

Promote psychological readiness to withdrawal from addictive behavior, regardless of associated pain.

Promote psychological readiness to withdrawal from addictive behavior, regardless of associated pain. Stimulate executive commitment to change.

Stimulate executive commitment to change. Generate early process and customer product/service delivery improvement through application of selected specialized performance enhancement methods and tools and techniques.

Generate early process and customer product/service delivery improvement through application of selected specialized performance enhancement methods and tools and techniques.

A military pincer movement surrounds its target with two flanking thrusts, or arms, simultaneously invading from opposite sides and enveloping (enfolding amoebae-like) the object (the organization, in our case) in victorious embrace. The goal is total absorption of psychological readiness to bear the pain of change throughout the organization.

Management transformation conventional wisdom states that change must begin at the top, rather than at the bottom of organizations. The pincer strategy simultaneously initiates change at both ends, which offers both managers and workers opportunities to direct and control transformation.

The upper (executive) pincer arm penetrates the organization through the CEO and immediately reporting executives (vice presidents and senior managers). Endorsement, readiness to commit, and, eventually, full commitment to change are its principle aims. Increasing levels of executive endorsement and commitment are its milestones. Executive endorsement (words) must, at some time, metamorphose into executive commitment (action). No arbitrary time for reaching this critical juncture exists. Organisms develop at their own paces, each unique unto itself.

The lower (worker/supervisor) pincer arm invades at the laborer level, penetrating quickly through first-line supervisors and middle managers. The immediate purpose is to stimulate readiness for implementing fundamental changes in daily work processes. The idea is to have them experience numerous small successes (and some failures) in visibly improving self-selected aspects of their daily work lives and customer deliveries to:

Make them feel good about themselves.

Make them feel good about themselves. Make them aware that they can control their lives.

Make them aware that they can control their lives. Open their minds to possibilities earlier deemed impossible or impractical. Formal and informal teaming processes, such as the Process for Innovation and Consensus (PIC), are superbly designed for this task.

Open their minds to possibilities earlier deemed impossible or impractical. Formal and informal teaming processes, such as the Process for Innovation and Consensus (PIC), are superbly designed for this task.

Successes are immediately observed by workers creating their own real process and outcome improvements, lessons learned, shared trust, lowered shields, safe vulnerability, and enriched individual senses of personal fulfillment. Typical change activities should be short, incremental, concrete, and pertinent to people’s work.

Both pincer arms eventually penetrate up, down, and sideways through the entire organization, overlapping and engaging virtually everyone in stimulating universal commitment and participation. Performance improvements and commitment symbiotically reinforce each other. Action, purposefully directed by philosophy and theory, defines the effort.

Comparing Pincer Arm Results

Lower-arm progress typically outpaces upper-arm advances. Leaping from executive endorsement to commitment is the toughest nut to crack. Executives reach pinnacles of success within operating hierarchical cultures with values, norms, and standards they naturally respect and appreciate. They do not easily discard them for anyone. As Deming used to quip, “Why should they?” After all, they gained their elevated positions, status, and income in the very systems about to be changed.

Repeatedly demonstrated new and improved ways become, however, harder and harder for opponents to deny and ignore. Dedicated, persistent, philosophically directed, and well-designed change processes eventually turn everyone except those few who, for their own reasons, choose not to move under any circumstances. Lacking such perseverance, those who simply mouth the symbols of change, while denying the spirit of the change and fooling themselves into believing their vacuous rhetoric, slide quietly back into their womb-like comfort zones. I found that they tend to voluntarily leave or fade into the background.

Remember that attempting to change without sufficient readiness to bear pain and opposition is fraught with danger (see Figure 1.1, cell 4). For everyone’s sake, and for your own peace of mind, (except in the most extreme circumstances) leave opponents of change alone (S/L #15, Appendix I). Their ability to withdraw from addictive behavior and accept the loss of old ways is different, and they need more time. Give them some space; they are grieving over loss of the old ways and must work through that grief to acceptance (see Appendix III). I find that serious opponents, as shown in Chapter 1, typically comprise only 10–15 percent of the population, and most of them come around with demonstrable improvements. Concentrate instead on the 85–90 percent who are either change champions or healthy skeptics.

PINCER STRATEGY COMPONENTS

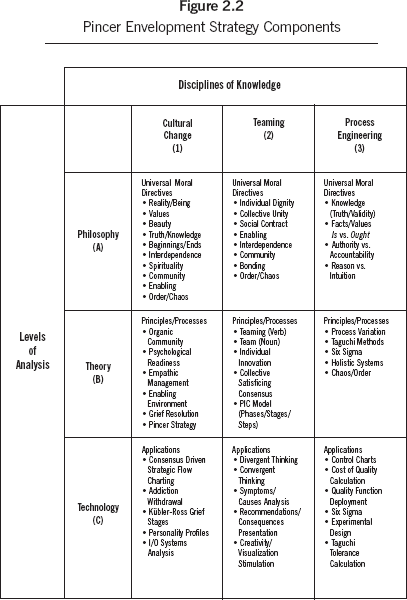

Of what, exactly, are the pincer arms composed? What specific theories and tools for change do they employ? Three disciplines of knowledge contain both the elements of commitment and the tools required to transform organizations. Each of these disciplines must be understood, and acted on, at three levels of analysis.

The three disciplines of knowledge are:

1. Cultural Change—altering individual habitual attitudes and behavior.

2. Teaming—enabling individual innovation and collective consensus.

3. Process Engineering—ensuring output uniformity and improvement by controlling process variation and by employing specialized statistical, mathematical, and engineering technologies.

The three levels of analysis, at which each of the three disciplines of knowledge must be understood and applied, include:

1. Philosophy—a set of coherent, universal, and transcendent normative (moral) management principles directing all change efforts.

2. Theory—a set of rigorous, empirically verifiable management concepts.

3. Technology—a collection of tools and techniques and methods for verifying and conducting theory-driven management practices.

EXPLAINING THE LEVELS OF ANALYSIS

Philosophy embodies the highest moral ends to which any enterprise may aspire (see Chapter 1). Normative statements inquire into what one should or should not do. They rest upon a system of ethics that prescribes, in absolute universal terms, what constitutes good, right, and proper behavior.

Theory, here, as in any scientific discipline, provides the rigorous logic driving the transforming strategies and processes. It opens a window into reality that allows us to order, explain, control, and predict events that might otherwise be inexplicable. Theory helps us arrive at otherwise nonobvious conclusions and provides intellectual and imaginative vision and direction. It is our road map to discovery. Theories include logically derived models that predict certain outcomes under specified conditions. Some models are mathematically stated—e.g., e = mc2—while others, such as Chapter 5’s PIC teaming model, take diagrammatic form.

Theories also provide empirical (pertaining to our five physical senses: sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste) tests for verifying the model’s predictions as observably true or false under specified conditions. Verification of the PIC model’s predictions rests in the outcomes experienced by those properly and accurately performing the teaming techniques offered in Chapter 6.

Technology involves the application of specially designed, theory-consistent, methods and tools and techniques to manipulate specified events and conditions in the world of experience. These are the verification devices, specified earlier, that test the accuracy and completeness of the model’s predictions. The PIC model asserts that teaming innovation and consensus will occur if people use appropriate technological instruments in prescribed ways under certain conditions. The test of the pie is, however, in the eating—no less so for teaming. Results matter!

These three levels of analysis, although analytically distinct, form an overlapping set of perspectives through which the three disciplines of knowledge are analyzed and employed. Figure 2.2 shows that:

Fully transforming an organization requires nine separate, but integrated, areas of consideration (three disciplines at three levels).

Fully transforming an organization requires nine separate, but integrated, areas of consideration (three disciplines at three levels). Techniques depend on theories that, in turn, need philosophical direction.

Techniques depend on theories that, in turn, need philosophical direction. Teaming, if attempted without attention to process engineering and cultural change, will produce only truncated satisfactions (explaining why so many teaming efforts evaporate).

Teaming, if attempted without attention to process engineering and cultural change, will produce only truncated satisfactions (explaining why so many teaming efforts evaporate).

EXPLAINING THE DISCIPLINES OF KNOWLEDGE

Process engineering is the most fully developed discipline of knowledge. Current literature is replete with statistical, mathematical, and experimental process models and techniques. The most familiar tools in the arsenal are statistical process control charts, first introduced by statistician Walter Shewhart and later interpreted by Deming. Control charts are prime examples of theory-driven (the theory of process variation) management improvement tools.

The theory of process variation explains a condition that anyone working for even a few years has experienced, i.e., the feeling that you are trapped in a system that prevents you from succeeding, no matter what you do.

Briefly, the theory says that 85–90 percent of all system breakdowns (including management systems) are caused by the initial conception and design of the system, rather than by some event or individual action taken at a particular work station. In other words, “Good parts fail in bad systems” (S/L #16, Appendix I).

Consider an example in which widgets moving on an assembly line tend to jam at Charley’s workstation through no fault of, or action by, Charley. Or remember Lucille Ball’s famous I Love Lucy television chocolate-assembly line skit in which the accelerating line speed makes it impossible for either Ethel or Lucy to pick up the chocolate pieces and put them in boxes? Line speed was programmed to increase faster than any human being could possibly accommodate. No amount of finger pointing, training, rewarding, or punishing could help Charley, Ethel, or Lucy succeed. Yet, that fact did not stop their panic over what the boss would say; he would blame them and scream at them, regardless of reality.

Serious consequences, even disasters, can flow from this simple principle. The underprovisioning of the Titanic’s lifeboats, for example, followed from design assumptions that the ship was virtually unsinkable and could, in the event of any accident, easily stay afloat until rescue arrived. Therefore, crew members were helpless, trapped in a system not of their making but destined to kill them nonetheless. Nothing they did could possibly prevent the loss of fifteen hundred lives in the two to three hours from hit to sink. System design destroyed them.

Problems aside, no natural, mechanical, electronic, or human process operates with perfect consistency. Barring major traffic problems, for instance, daily driving times from home to work vary by seconds and minutes, depending on how we design our travel arrangements. Daily travel durations randomly vary, according to chance occurrences along the way—i.e., red lights one day, green the next. Process variation, then, measures operating consistency of processes varying under randomly occurring influences. Persistent late arrivals at work require rethinking the overall process rather than blaming Tuesday’s driver. These randomly occurring, design-provoked causes of process variation (and failures) are called common causes.

The theory of process variation also states that special causes account for the other 10–15 percent of process variations and failures and can be traced to specific events or individual actions. If Charley, for instance, fails to properly maintain his equipment, or someone else inadvertently does something to affect the line at Charley’s station, then that special cause can be isolated, tracked, and corrected at the appropriate location without design considerations. Properly maintained control charts clearly separate and identify common and special causes of process variation and failure.

Imagine, for a moment, the implications of this theory. Jargon removed, it declares that the vast majority of failing office and plant processes cannot be legitimately traced to individuals working within the system—finger pointers beware! They are instead traceable to system-design errors. And, who controls the system? Managers, of course! Workers work within the system; managers control it. Hence, managers bear the burden of correcting most performance variations and failures. Those clinging to traditional bureaucratic blame-the-worker ways choke on such ideas.

This in no way implies less worker accountability. It simply means that workers cannot legitimately be held accountable for events over which they have no control—even when symptoms of the failure inadvertently appear at their workstations. One must, therefore, ask executives the following question: “Since statistical process control charts accurately isolate and identify common and special causes of variation and potential failures, why are they not strewn all over the place?

The answer is, of course, culture. Hierarchical command/obedience attitudes and behaviors simply do not accept process variation’s manager/worker relationship assumptions. These are the kinds of embedded habitual addictive human propensities that change demands be reversed. No wonder change is so painful—and so rare. Smoking addictions are probably easier to overcome.

Teaming, the second discipline of knowledge, is an act that occurs whenever two or more people communicate with each other, formally or informally, in an enabling environment characterized by individual innovation and collective consensus (S/L Definition #7, Appendix I). It now enjoys increasing interest, literature, and sophistication, especially in quality management and project management circles. Too often, however, the noun team—equated with groups, formal meetings, and institutionalized problem solving—restricts and distorts its operating values and outcomes. You know by now that I view the verb teaming in a far broader context, one within which groups, formal meetings, and problem-solving activities are merely restricted applications. Chapters 5, 6, and 7 present all of the theory and practices you need to conduct the widest possible number of philosophically driven teaming associations.

Individual innovation, in this context, means that all participants are (and feel) equally free to both say whatever they think and to listen to what others are saying. Consensus means that a 100 percent working (satisficing) agreement occurs on all collective decisions. This is not a utopian goal; it happens regularly in properly conducted teaming ventures. A complete step-by-step mechanics for achieving satisficing consensus is provided in Chapter 6, while the concept is fully explained in Chapter 5.

Cultural change, the third discipline of knowledge, takes us far afield from pure management theory into the realm of psychology, anthropology, and other behavioral disciplines. Although, as stated earlier, I am neither a psychologist nor an anthropologist, I can tread carefully through pertinent literature, and suggest lines of common association that might provide insights into the dynamics of corporate culture and resistance to change.

As previously noted, the most fruitful approaches to cultural change at the theory and technology levels of analysis involve addiction, addiction withdrawal, the tendency to cling to even unpleasant known ways of doing things over strange unknown ways, and working through the grief that accompanies the loss of old familiar ways.

One critical, relevant, and driving psychological principle of cultural change is that people must engage, face, and work through their deepest hidden feelings if they are ever to withdraw and recover from addictive behavior. This means that they must become psychologically ready to challenge the underlying fears that prevent them from acknowledging submerged feelings, and be willing to suffer the pain of withdrawal. Here is a well-developed theory explaining the source of behavioral inertia and how to overcome its grip on people—a way to engage, challenge, and overcome another mantra typically chanted in management transformation seminars, the all-encompassing resistance to change (discussed in Chapter 3).

Cultural anthropology offers significant insights into the analysis of adaptation and survival in human communities. Comparative politics contrasts how various peoples authoritatively allocate competing individual and collective values and interests—the very heart of those agonizing parochial barriers to communication raised across bureaucratic boundaries, which erode risk taking and accountability. Economics directly addresses the familiar cries of, “We don’t have enough,” by examining the production, distribution, and consumption of scarce material resources.

Engineering control-systems theory provides precise models for analyzing the feedback principles driving both systems that run amok and systems that self-correct. Political theory applies these same principles to the analysis of human systems with substantial success. The science of chaos provides profound insight into the study of turbulence, discontinuity, randomness, unpredictability, simplicity versus complexity, and the nature of ephemeral patterns of order—all direct descriptors of organizational behavior and environment. And, these bring us back to management philosophy.

Ontology, for example, the field of moral philosophy that examines the nature of being, provides direct assistance to those contemplating the mission and vision of their organizations. Epistemology, the study of knowledge and the nature of truth, provides a foundation for understanding the meaning, character, and use of verification and measurement. The contribution of ethics to the field has already been discussed. Aesthetics looks at the nature of beauty, which probes the roots of joy, wonder, spiritual uplifting, inspiration, and awe—characteristics so vital to personal work fulfillment.

These factors have led me to approach client organizations from the viewpoint of first ascertaining whether substantial and sufficient numbers of their populations are psychologically ready to challenge their addictive habitual attitudes and behavior. The developing theory suggests that the reasons many people, who are attempting to change their organizations, face frustration and despair is that they are attempting that which they are not ready to do.

Therefore, the first job is to enable people to become psychologically ready to suffer the pain of withdrawing from their addictions. This is done in a carefully measured process through application of various mixtures of the disciplines of knowledge at diverse levels of analysis, targeted at selected regions of the organization, through application of the pincer envelopment strategy.

Experience has shown that the best way to enable people to choose to address their addictions is to enlighten by example. The idea is to place them in an environment conducive to promoting behavior based on new attitudes; the PIC does this. Participants must arrive at a state of enabling, such that they choose, themselves, to change—easier said than done. It works only when they understand what is being attempted, when the facilitator is sufficiently skilled in the application of the theory-based techniques being employed, and when a sense of mutual trust, respect, and dignity pervades the atmosphere. Repeated experiences begin to erode individual and collective walls imprisoning people in their old ways. Perceived threats to survival and prosperity are chipped away by repeated positive reinforcement.

The change process is stressful. People are not being asked to simply learn new ideas. They are being asked to unlearn and suffer the loss of comfortable old habits of attitude and behavior and to adopt new, strange, uncertain, and risky new habits of attitude and behavior. You must remember that they cannot be directed into this change; they can only choose for themselves to change themselves.

The facilitator’s role is to create an environment that puts people at enough ease to so choose. The word facile refers to making something easy. Cultural change, however, is not easy. Facile, as applied here, means putting people at ease and then giving them the skills, knowledge, and ability to create their own changes.

RESISTANCE TO CHANGE: “THERE BE DEVILS!”

Early European mariners, believing that the world was flat, looked westward over the Atlantic Ocean with great longing and anxiety. They wanted to explore but feared falling over the edge of the world into hell or something worse—the unknown. Some contemporary maps of the ocean contained the statement, “There Be Devils.” I sense that some of those who intensely resist organizational change anticipate the same thing: an unknown void at the edge of their work world, to be devoutly feared. “There Be Devils.” Let us turn, then, to that old monster in the closet—resistance to change—and see what we can do about it.