MISTAKE #6

No Mistaking

Knowledge is knowing a tomato is a fruit. Wisdom is not putting it in a fruit salad.

—Miles Kington

When it comes to investing, much of the game is simply not messing things up. We have covered that in detail thus far. Of course, the goal is not only to avoid getting in the way of success; it is to maximize the odds of success.

Having gone over the key mistakes to avoid, we can move on to discuss how to optimize your results.

Rule #1: Have a Clearly Defined Plan

If you don't know where you are going, you'll end up someplace else.

—Yogi Berra

You don't start a race without knowing where the finish line is. You don't go on a hike without knowing your destination and the conditions you may encounter. You don't start driving somewhere without knowing where you are going.1 Nonetheless, most investors invest without an endgame laid out in advance. Without a destination, it is easy to drift off course. Without a plan, it is easy to change the strategy midstream, increasing the odds of messing everything up.

Before you invest one dollar, you must have a plan. A plan does not need to be a 150-page road map of how you will invest every minute for the rest of your life. A plan can be very straightforward.

Step 1—Begin with determining the starting line, which is where you are today. Build a net worth statement that lays out all of your assets and liabilities.

Step 2—Know your goal. A goal must be very specific and realistic. An example of a goal that would not work well is: “I want to retire with a lot of money.” Come on, people! We need to have a clearly defined purpose. Something like this will work: “I would like to retire at age 62 with an after-tax income of $100,000 per year, adjusted for inflation, and I want to assume Social Security will not be there for me.” Now that is something we can work with!

Step 3—Run a projection showing how on track you are for that goal. There are online tools to help you do this, or your advisor can do this with you. Be sure to exclude assets that are not available to fund retirement. For example, if your net worth statement shows you have $800,000 today, but you plan to spend $150,000 on your kids' weddings and education, the projection should start with the money you have today that is available for retirement, which is $650,000 ($800,000 less the $150,000 you need for the kids). Then, include the money you are saving regularly, whether it is to your retirement plan at work, an IRA, or a taxable account reserved for retirement savings. These projections can get more sophisticated if you include Social Security, other income like pensions or rental income, potential inheritances, and other variables. Using these projections, we can determine how on track you may be for your goals.

Step 4—Determine if you need to adjust your goal. For example, if your projection shows that to hit your goal, you need to have an investment rate of return of 20 percent a year, well, change the goal because it very likely isn't going to work out. You can make adjustments by lowering your income need, saving more, pushing your retirement date out, or some combination of these.

Step 5—Move on to building the portfolio. Note that your plan needs to be revisited regularly (more on this later).

You may have different plans for different portfolios. For example, you may have separate investments set aside for education, which will have a different starting amount (what you have set aside) and a different goal (the amount of education you want to fund). You may have yet another goal for a second home, a wedding fund, or a trust set aside for kids or grandkids. Each of these portfolios should be constructed after a concrete plan has been laid out to clarify the objectives.

Finally, for those with excess wealth, which means having money beyond the pool of money you need to achieve all of your goals, it is acceptable to have the excess wealth portfolio's goal to simply “beat the S&P 500” or anything else you may fancy.2 The key is to make sure that you have a solid portfolio in place to get you on track to financial security. After that, your excess wealth can be invested in a variety of ways.

In each case, whether it is for retirement, education, excess wealth, or any other portfolio, first determine a specific goal. Everything else flows from that purpose.

Rule #2: Avoid Asset Classes That Diminish Results

There are five major asset classes: cash, commodities (like gold and energy), stocks, bonds, and real estate. I will start with the two asset classes that should never be included in an investor's portfolio and then cover how to construct an allocation targeted toward your goals.

Cash— The Illusion of Safety

The one thing I will tell you is the worst investment you can have is cash. Everybody is talking about cash being king and all that sort of thing. Cash is going to become worth less over time. But good businesses are going to become worth more over time.

—Warren Buffett

When we think of risky asset classes, we tend to think of commodities, real estate, stocks, and even some bonds. Cash may be last on the list. Cash, however, has many inherent risks as well.

First and foremost, cash is the worst-performing asset class in history. Over long periods, cash has always underperformed all other major asset classes. The more time you spend with a significant portion of your holdings in cash, the higher the probability your portfolio will underperform.

Second, holding cash for long periods guarantees that you will not keep up with inflation. Cash guarantees the loss of purchasing power. In essence, your cash becomes worth less and less each year as prices go up, and your cash does not. Imagine you put $100,000 in the bank and earn 1 percent or so a year for ten years. When you pick up your cash, you may feel pretty good. However, the 1 percent or so you earned did not keep up with the cost of a stamp, a suit, a candy bar, health care, or education. You may think you made money, but you lost purchasing power.

One reason many “investors” hold cash is to time the market. They do this even though there has never been a documented, real-world study done by anyone showing that repeatedly moving from the market to cash and back to the market works. After all, you need to be right about when to get out, then when to get in, and do it over and over again. If you get burned just once, it can be “over,” and your performance permanently affected.

Finally, many investors hold cash in the event of financial Armageddon, a situation when the stock market goes to zero or near zero and never recovers. In reality, if we live in a world where Walmart, Nike, McDonald's, Exxon Mobil, and the rest of the world's dominant companies go down and never recover, it will likely accompany a default by the U.S. government on treasury bonds. How can the U.S. government make its debt payments on its bonds if the major U.S. companies have collapsed? Who exactly would be working and paying taxes to cover the debt payments? In this event, cash is worthless as the FDIC guarantee would essentially mean nothing. If you do not believe America's largest corporations can survive, then the natural conclusion is that the U.S. economic system itself cannot survive. In that event, cash may be the worst asset to own.

Despite all of this, Americans are currently sitting on nearly $5 trillion in cash, surpassing the previous high set during the 2008 financial crisis. In typically tragic fashion, the peak of the move to cash in 2020 was the week of May 13, causing scores of investors to miss out on the subsequent 45% rebound in the markets.

Cash gives people comfort because, for goodness sake, it does not move around at all. It is easy to understand, and it does not “go down.” But there is more to the story than that. While cash brings comfort, it does not keep up with inflation, continually loses purchasing power, drags down long-term investment returns, and is of no value in the event of an actual economic collapse. Keeping short-term reserves on hand is a good idea. Hoarding cash as a long-term investment—not so much. Eliminate cash as a consideration for your investment portfolio.

The Illusion of Gold as a Way to Grow Wealth

What motivates most gold purchasers is their belief that the ranks of the fearful will grow. During the past decade, that belief has proved correct. Beyond that, the rising price has on its own generated additional buying enthusiasm, attracting purchasers who see the rise as validating an investment thesis. As “bandwagon” investors join any party, they create their own truth—for a while.

—Warren Buffett3

In case you had not noticed, there is a gold rush taking place, with investors adding more and more of the precious metal to their portfolio.

Many investors are flocking to gold as they worry that the dollar is losing so much value it may become worthless. Others worry the global economy will collapse, and gold will be the one real currency. Others view it as the safest place to be should we see high inflation.

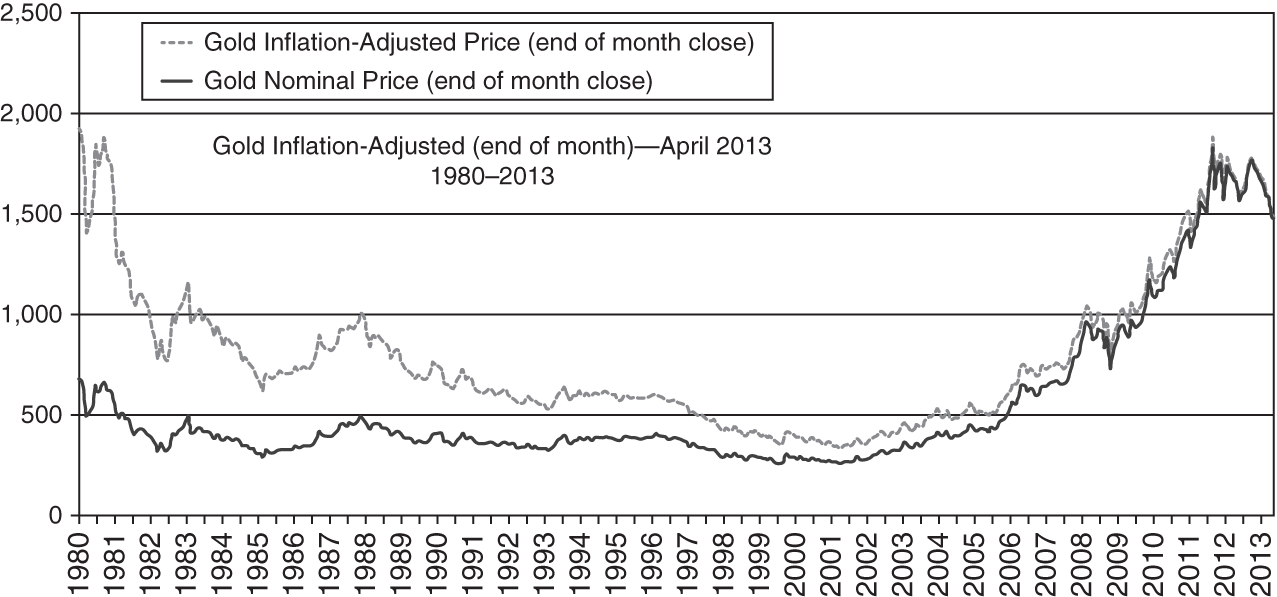

Unlike companies, real estate, and other commodities (like energy), gold itself is nearly intrinsically worthless. Companies and real estate can create income. Energy companies have the potential to produce income. Oil itself is used as one of the most critical resources in the global economy. Gold produces no income and is not a critical resource. Historically, gold has performed worse than stocks, real estate, energy, and bonds, barely keeping pace with inflation (see Figure 6.1).

Every time in history it has outperformed substantially, it has ultimately collapsed. Finally, while gold has proven to underperform stocks and even bonds dramatically over the long run, it is still one of the most volatile asset classes. Gold belongs only in the portfolios of fearmongers and speculators. If you own gold in your portfolio, expect not to get paid an income, pay higher taxes on your returns, take a more volatile ride than the stock market, and get a long-term return lower than bonds. No thanks.

Source: Gold vs. Inflation, 2013. © AboutInflation.com.

Rule #3: Use Stocks and Bonds as the Core Building Blocks of Your Intelligently Constructed Portfolio

Bonds

Several studies have thoroughly documented that asset allocation is the primary driver of investment performance, accounting for 88 percent of a portfolio's returns. For example, if you own a handful of large-cap stocks, a large-cap mutual fund, or a large-cap index, you will get close to the same return most of the time. The other 12 percent of the portfolio's returns will be driven by other factors such as security selection and market timing, two factors that usually hurt performance.

Proper portfolio construction is part art, part science, and certainly never perfect, but it goes a long way toward following a plan that makes sense for your particular situation. Much is made of which asset classes are “good” or “bad” when in reality, it's your goals, not the various markets, that should drive the exposure to any given asset class in a portfolio. For most, but not all, investors, owning multiple asset classes to achieve various goals makes the most sense.

Bonds deliver a positive return about 85 percent of the time. With a bond, you are loaning money to a company or other entity. A treasury bond is a loan to the federal government; a municipal bond is a loan to a municipality such as a city or a state. A corporate bond is a loan to a corporation like McDonald's or Nike; a high-yield bond, also known as a junk bond, is a loan to a corporation that has to pay higher interest to attract investors to loan them money.

A lender is in a more predictable position than a stockholder. As long as the company stays around, the lender gets paid back with interest. A stockholder never really knows what will happen, as the stock can fluctuate all over the place. It is for this reason that, over the long run, bonds are expected to underperform stocks. You should not own bonds on the expectation they will do otherwise. So, if bonds are expected to underperform, why in the world might you buy them? Well, several reasons. First, while stocks are very likely to perform well over ten years, there is a lot of precedent for prolonged periods of misery (see 9/11, the tech bubble, or 2008/2009 for a modern-day refresher). Short-term income needs must be met for three to seven years so that the investor is never at the mercy of the stock market's often random gyrations. Between the bonds and your other income, you can cover your needs, whether or not there is a flash crash, someone flies into a building, a global pandemic, or any other event that occurs.

Basically, bonds are insurance. We are giving up the expected return in exchange for dramatically increasing the likelihood the investor's needs will be met in the short and long run. As an example, let's say you are retiring next year, and so long as you earn 6 percent per year, you will have the $120,000 per year you want in retirement. While stocks will likely outperform bonds throughout your retirement, we know two important things: (1) Stocks may underperform bonds in the first few years of your retirement, and (2) you don't need to be 100 percent in stocks to net a 6 percent return. Because of this, you should look at owning enough bonds to cover about five years of retirement to avoid the scenario of selling stock holdings during a bear market that may appear in the beginning stage of your golden years.

Finally, while much of this book is focused on the case for indexing your stock portfolio, the bond market is a different animal altogether. There is a fair debate about whether active management adds value in this space, so bond mutual funds, institutional funds, index funds, or individual bonds may be appropriate for your bond allocation.

Stocks

Stocks are the subject of ceaseless predictions when actually, they are the most unpredictable and, at the same time, predictable asset class. No one, absolutely no one, can predict the short-term movement of stock prices. As a reminder, anyone who tells you otherwise is likely an idiot or a liar (not sure which is worse, really). Yes, those are strong words, but with all the noise, it is vital to understand this as it impacts the allocation to this critical asset class. Because stocks are not predictable in the short run, investors should not own them to meet short-term needs. However, over the long run, stocks are expected to perform far better than bonds. Because stocks are riskier than bonds, they come with an implied “risk premium.” If bonds were expected to perform as well as stocks, no one would ever take on the volatility that comes with owning stocks. Over the short run, stock prices are completely unpredictable. Yet over the long run, as a group, they have always done one thing: Go up—a lot.

While this inevitable outcome has persisted for over a century, the constant corrections, crashes, and day-to-day movements drive out the fainthearted or cause them to jump ship at the worst possible time. Part of having the patience to make it through all this is to have stock market exposure only for the portion of your portfolio allocated for income needs more than five years out, depending on various factors. If you are not at the mercy of the market over the next few years, and we know over the long run that the market has done nothing but go up, it becomes far easier to get through the rollercoaster ride along the way.

Suppose an investor has more than 10 to 20 years before part of the portfolio may be needed. In that case, this part can be invested in subsets of the market that are extremely volatile but have a long, well-documented history of rewarding the investor for their patience. Examples include mid-cap stocks, small-cap stocks, microcap stocks, and emerging markets stocks. The higher volatility should reward the investor with a higher return.

For example, if an investor has more than 20 years to retirement, they might have a substantial part of their portfolio in emerging markets. Some investors have wealth they will never spend or parts of the portfolio they will never touch. For situations like this, it can make sense for even a 75-year old to have a significant portion of their portfolio in small stocks or emerging markets stocks. However, buyer beware! If you cannot stand the heat, get the heck out of the kitchen. While on paper and over time, this strategy works well, it is not for the fainthearted. These sub-asset classes are often uncorrelated, can move quickly, and may underperform for long periods. An excellent way to know if these sub-asset classes make sense for you is your reaction to a drop. If you get excited at the opportunity to sell off bonds and buy more small caps and emerging markets while they are getting hammered, they will work well for you. If you find yourself generally freaking out about the drops, you will not last in the position long enough for it to work out, and you will cause your portfolio undue harm.

Alternative Investments

An entire book could be written on alternative investments.4 In general, however, you can break them down into two camps: alternative ways to invest in public markets (like hedge funds) and investments that earn money outside of the public markets. Since I've already given you my perspective on hedge funds, I'll stick to the second type: investments outside of the public markets. Just as domestic companies tend to have an international counterpart (think Exxon and BP, Hershey's and Nestlé, etc.), public investments also have private counterparts. While you have stocks, bonds, and real estate in the public markets, you also have private equity, private lending, and private real estate. Let's take a quick look at each.

Private equity is owning shares of a company that isn't traded on the public exchanges. This may be either through the entrepreneur who owns the business or through one of the thousands of private equity firms that buy and sell shares in growing businesses. Investors in this space look to buy into or exit a firm at certain “stages.” Venture capital investors are early-stage investors who may be putting money behind nothing more than an idea for a business with no existing product or revenues. Growth equity and buyout equity investors are later-stage investors looking to put money into a growing company to help scale the business to the point that it can be sold to another company or private equity investor or become publicly traded. A growth equity fund typically only has a minority ownership interest in the companies it invests in, meaning the business's day-to-day operational control remains with the original ownership team.

On the other hand, a buyout equity fund will typically buy a majority interest or even the entire company, giving them greater control over the operations of the business. Buyout funds also tend to employ leverage—which means they borrow money in addition to the capital they raise from investors—to purchase businesses. The fund managers use this strategy to maximize their financial resources and improve their return if their deals are profitable.

As we've already discussed, venture capital investing—despite the handful of “unicorn” companies who have enjoyed outsized success and made the space seem wildly more profitable than it is in reality—is almost always a sure path to underperformance. On the other hand, growth equity can have a place in a portfolio for higher-net-worth investors. Over the last 20 years, the data shows that growth equity firms have outperformed public markets consistently.

There are many reasons for this, but the short version is that successful growth equity firms can add significant value in scaling profitable businesses, which means their portfolio companies can increase in value by many multiples in a comparatively short period. For example, a restaurant owner who has built a successful business might have a couple of locations in one city. A growth equity firm can help reconfigure the business or service model so that the concept can be easily replicated in markets across the country. With the firm's help, the owner can open locations nationwide or franchise their operations. What was once a successful small business is now a major national brand, and the private equity investors reap the reward from the return on their investment.

This scenario is far removed from the many venture capital investments that often fail to survive or even make it to market. For example, look at Quibi, the short-form content mobile streaming app. Despite a litany of A-list celebrity and industry mogul involvement, the service shut down six months after launch, after having taken in nearly $2 billion in funding.5

Private lending can be thought of as an alternative to the public bond market. In this case, I'm primarily referring to middle-market lending funds. The idea behind these funds is to provide a source of capital to mid-sized businesses. If you are a business that needs to raise money, you can sell a portion of your company (typically to a private equity firm) or borrow money. Many private businesses find themselves too large to receive small business loans, too small for big bank loans, and unable to issue bonds in the public market. Middle-market lending funds fill that gap by providing loans to these businesses to fund operations or expansion. Like traditional loans, these may be secured (meaning they are backed by a piece of property, equipment, or other assets) or unsecured. Private lending has emerged as an asset class over the last ten years, so there's not enough history to guarantee these funds will outperform publicly traded bonds. However, based on the loan characteristics, the probability is reasonably high that these funds will deliver better risk-adjusted rates of return over time.

Private real estate can be broadly defined as any investment in real estate outside of publicly traded REITs. Some examples are a farmland lease, an apartment or office building, or even a rental property down the street. Much has been made of real estate as an asset class, primarily fueled by a narrative that it is somehow less risky than owning stocks. Every investment carries risk, including owning real estate; the risks are just different than owning stocks. Part of what makes real estate attractive as an investment is the use of leverage. Because most people finance the purchase of properties, a small amount of money can be used to buy a relatively large amount of real estate. The use of leverage also magnifies gains and losses. If you put 20% down on a property that increases 20% in value, you've made 100% profit; if instead, the property value goes down by 20%, you lose your entire investment if you're forced to sell. It's not uncommon to see real estate developers go bankrupt if their property portfolio ends up “underwater,” where they have more debt than their properties are worth.

Private real estate funds exist to deploy investor capital into real estate projects. These funds may be pooled to construct a shopping center, hospital, or office building. Typically, the fund manager is looking to build the property, lease it to a tenant for a certain number of years, and then sell the development to someone else. These types of funds may be attractive to high-net-worth investors looking to add exposure to a specific type of real estate in their portfolio. Or the fund may be deploying capital into a project in economically disadvantaged areas— known as “opportunity zones”—that may qualify the investor for certain tax breaks.

History suggests that the types of private investments discussed here can outperform their public market counterparts. If you have the access, time, and resources to get the best-in-class offerings, exposure to these assets can improve the performance of your portfolio. However, these investments introduce certain complexities and complications as well. For example, to invest in many of these funds, you must meet minimum net worth or income thresholds to satisfy the legal requirements to be an investor. If you qualify, you can typically expect your investment funds to be tied up for at least 5–7 years before you can get your money back. These types of investments also increase the cost and complexity of preparing your tax return. Possibly most importantly, unlike investing in low-cost index funds—where history tells us the market is more likely to outperform active managers over time—with private funds, the experience, acumen, and execution of the manager is critical to the success of the fund. Having an experienced team to vet these opportunities and access to top-performing funds is essential for anyone interested in alternative investments.

Even if you meet all the requirements, investing in alternative assets isn't for everyone. For most investors, especially those who want to keep things low maintenance, a simple allocation of stocks and bonds can be far better than getting too cute with the portfolio. The goal is to increase the probability of achieving your goals. In the end, the wealth you have accumulated is a means to an end. You have some purpose for it. The asset classes and sub-asset classes you own should always be tied as closely as possible to your goals.

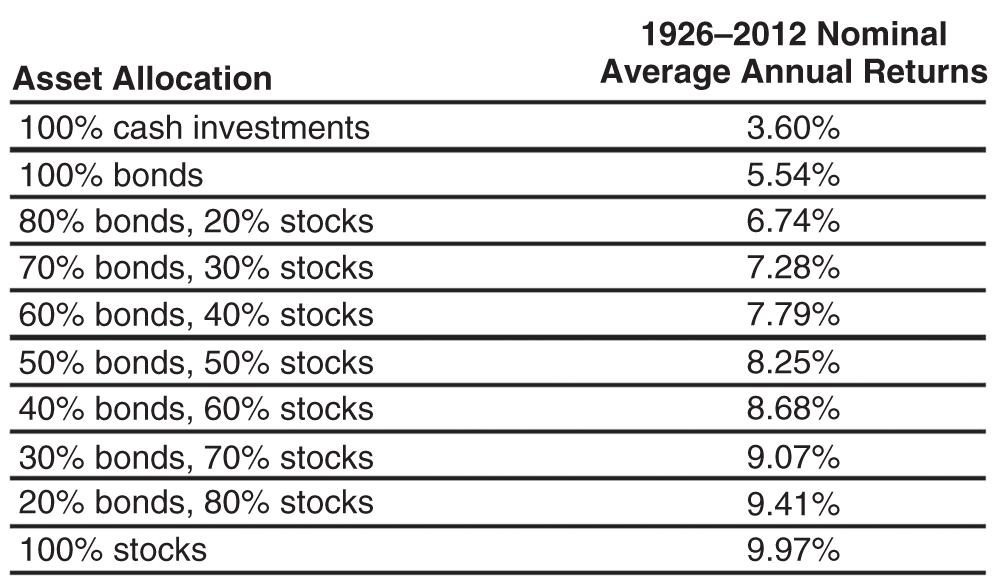

Source: Data from The Vanguard Group, Inc. 2013. “Vanguard's Principles for Investing Success.”

Putting It All Together

The individual investor should act consistently as an investor and not as a speculator.

—Benjamin Graham

Knowing the rate of return required of the various portfolios, we can work our way to a basic allocation.

Looking at the returns, it seems to make sense to go “all in” with the stock market (see Figure 6.2).

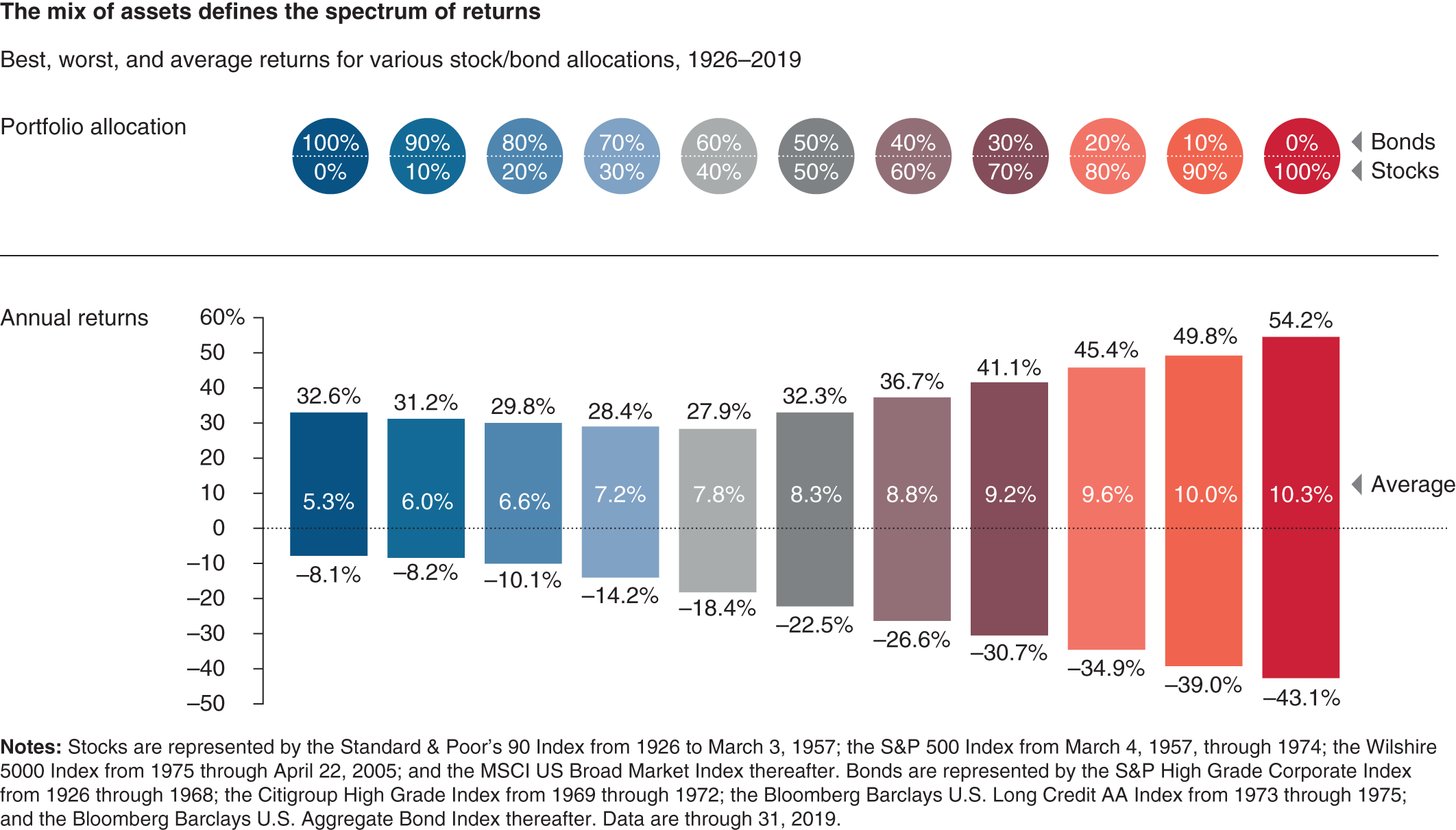

Of course, nothing is that easy. The higher the allocation to stocks, the more volatile the portfolio will be. For example, a 100 percent stock portfolio has ranged from its best annual return of 54.2 percent to its worst at –43.1 percent. In comparison, a 60 percent stock/40 percent bond portfolio has ranged from a 36.7 percent best to a –26.6 percent worst return, a much narrower range of performance (see Figure 6.3).

Rule #4: Take a Global Approach

Investors tend to have a home country bias, meaning they invest most of their money in companies that operate from their home country. For example, Australians own a disproportionately large amount of their portfolio in home country stocks, as do investors throughout Europe and Asia. U.S. investors, more than any other country, can justify a home bias because there is a disproportionately large share of the global economy and stock market equity that are domiciled in the United States.

Sources: The Vanguard Group, Inc. 2020. “Vanguard's Principles for Investing Success.”The Vanguard Group; Using data from Morningstar.

Nonetheless, U.S. investors should have international holdings as part of their portfolio for several reasons. First, we live in a global economy, and companies everywhere can and do make money. Second, international holdings often behave somewhat differently from U.S. holdings: the U.S. markets and international markets often “take turns” outperforming for short and sometimes long periods. This difference in returns can reduce portfolio volatility. Third, many international economies, especially the emerging market economies, have far higher projected growth rates than the United States.

One does not need to become an international exchange expert to create a global portfolio. By purchasing an index fund, an investor can instantly add global exposure. For example, if your allocation targets 60 percent stocks, you can assign 1/3 of that allocation to global stocks by buying an international ETF. The same can be done with your bond allocation.

Rule #5: Use Primarily Index-Based Positions

If the data do not prove that indexing wins, well, the data are wrong.

—John Bogle

As we covered in Chapter 2, actively trading securities in any asset class will likely yield lower returns. Choose index-based holdings for most if not all of your portfolio.

Rule #6: Don't Blow Out Your Existing Holdings

Know what you own and know why you own it.

—Peter Lynch

Once you have determined the right allocation for you, work toward it as quickly as possible. Any investments in tax-deferred accounts like 401(k)s, 403(b)s, IRAs, and the like can immediately be sold and repositioned. Any new money you add to the portfolio can be placed into the new investments as well.

However, resist the temptation to sell all the holdings in your taxable account. While it is true that the S&P 500 will likely outperform the large company stocks you currently own, it very likely may not outperform on an after-tax basis. For example, if your target is to have 30 percent of your portfolio in large U.S. stocks, your holding for that part of your portfolio is likely the S&P 500 index or a similar index. Let's say you already own large U.S. companies like Microsoft, Walmart, and ExxonMobil, and they have gained significant value. These capital gains would be exposed to taxes if sold. Assuming they are not too large a part of your portfolio, it makes sense to hold them and work around them. For example, if those holdings are valued at $50,000 and $30,000 are gains, you could lose about one-quarter or more of the increase to taxes if you sell. Instead, hold the positions and reduce the amount of the S&P 500 you were going to purchase by the same amount. The goal is to get as close as possible to the target portfolio without creating a tax hit that likely cannot be overcome. Yes, the S&P 500 may do better, but likely not by enough to cover the tax hit.

Another investment that may make sense to work around is an annuity. While many annuities have very high expense ratios and limited investment options, it may make sense to hold them if surrender charges are high. Wait to cash in until the surrender charges are zero or low enough to be offset by the savings in the new portfolio. If you are seriously ill, surrendering an annuity with a death benefit may not make sense at all. In short, while other investments may be better, once you have already purchased an annuity, there are many factors to take into consideration before selling it.

There are also scenarios where I have advised clients to hold large concentrated positions that make no sense to hold from a purely target-portfolio perspective. For example, a new client had $3 million of their $3.5 million net worth in one stock. They had hired my firm because the husband was dying, and he wanted to be involved in choosing an advisor to assist his wife when he was gone. I advised the couple to hold the security in the husband's name until his death. On his death, the stock received a step-up in basis. All the securities were sold without capital gains and repositioned into a new portfolio that made sense for her needs. Investing can at times be simple, but if tax or estate planning is involved, sometimes putting together a sound investment plan can do more harm than good due to the unintended consequences. Be aware of all the implications of portfolio repositioning before making changes.

Be wary of any advisor who recommends you “sell everything” regardless of tax consequences. It's irresponsible and lazy, and poor advice. Often, with customization, the portfolio can yield a far better after-tax result.

Rule #7: Be Sure You Can Live with Your Allocation

Know thyself.

—Socrates

I have three kids, and whenever we'd go to the amusement park when they were young, they'd examine the various rollercoasters. I could watch their minds at work. Some of the coasters are too boring for a 12-year-old, and some would get him excited. When he was younger, I would get a “maybe not this time” sort of look from him. Even kids attempt to make decisions as to the sort of ride they can handle.

In the past, I used to go on whatever rollercoaster they wanted. In recent years, I have often found that to be a regretful decision, particularly during the slow climb up some ridiculously high hill and the near vomit-inducing drop. Even then, though, I realize that getting off the rollercoaster and back on it in the middle of the ride is not a good idea. The odds are high that I will come out on the other end in one piece if I can follow it through to the end.

The markets are the same way.

The bond market is much like the kiddie coaster at Lego Land— almost anyone can handle it. The stock market is much like a big-time rollercoaster at Six Flags. The real estate market is like Space Mountain at Disney World: fast and in the dark. The commodity market is more like the Detonator: a ride that drops and lifts you unpredictably.

All of these rides have various levels of speed and volatility. Some find them thrilling; others find them nauseating. But in all cases, the rides generally reach a peaceful conclusion, even to the passengers who are wondering exactly what they just got themselves into.

The best time to evaluate the “rollercoaster” you are on is when the market is relatively stable. It is much easier to make that decision during a peaceful interlude than once the ride starts up again. And one day, it will definitely start up again.

This is easier said than done. Americans are great at forgetting things. It is a great coping mechanism that allows us to move on. After going on a rollercoaster with my son, I tell myself I won't do it again. But the next time I am at the amusement park with him, I agree to the stomach-dropping ride, not remembering how bad it felt the last time. Now, I no longer forget, and we make sure to take a friend of his along.

Smart investors customize their rollercoaster, taking parts of various markets to build a portfolio that meets their short-, intermediate-, and long-term needs. A portfolio can twist and turn, taking on the volatility necessary to meet the investor's specific goals. Still, it should be structured within the parameters that the investor is prepared to handle.

For many, the best portfolio is a portfolio that accomplished the intended goals with the least volatility possible. However, if the volatility is outside your bandwidth of tolerance, it is far better to adjust the goal or your savings plan than to make a mistake at the worst possible time.

Rule #8: Rebalance

If you do nothing else from here, your portfolio will probably work out fine. Still, you will likely end up taking more risk than you intended and paying more in taxes than required because you overlooked a key maintenance requirement: rebalancing your portfolio.

Rebalancing is a concept discussed a lot by advisors. Here is what you likely won't hear from most advisors: Rebalancing hurts your returns over the long run! And here is why: Over long periods of time, stocks outperform bonds. If you have a portfolio that is 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds, and you never rebalance, you may wake up 20 years from now with a portfolio that is 85 percent stocks and 15 percent bonds. There may be a scenario where it makes sense for you to have a more aggressive allocation 20 years from now than you have today, but it's unlikely. By rebalancing, you are intentionally keeping the portfolio aimed squarely at the target, thereby increasing the chances that you will hit your goal. It also increases the chances that you will not substantially underperform or outperform the goal.

Some investors rebalance periodically, such as every quarter or every year. I personally think that is overkill as it can often create unnecessary transactions and sometimes taxes. If a rebalance will create taxes or extensive transaction costs, consider skipping it unless your allocation is totally out of whack. On the other hand, if the market drops, don't wait! Take the opportunity to rebalance at that time, intentionally increasing your exposure to the weaker asset class, usually stocks, when they are down. If they keep going down, rebalance again! This is called opportunistic rebalancing and yields a better rate of return over time than periodic rebalancing. If this is just too much to deal with, simply confirm that your goals haven't changed and rebalance one to four times a year and get on with life!

Rule #9: Revisit the Plan

You don't need a parachute to skydive. You just need one to skydive twice.

—Source unknown, author unknown

Revisit your plan and projections once a year or any time a significant change in your life occurs.6 At your review, you will notice that your starting point may have changed. Your portfolio likely performed better or worse than expected over the previous year. You may have received an unexpected bonus, an inheritance, or had a liquidity event (for example, the sale of a property). The starting line has changed.

Perhaps your objectives are different now too. Maybe you want to retire sooner than you initially thought or are now going to work part-time in retirement. Perhaps the college your daughter wants to go to is twice as expensive as initially thought. Maybe the baby you were going to have ended up being triplets. Maybe now you are married, or newly single, or healthier, or more ill than expected. The finish line may have moved.

All sorts of things can change that should result in changes to the portfolio. Note that the emphasis on changes to the portfolio should be based more on personal changes than changes in various markets.

For example, let's say a 60-year-old investor has a goal of living on $100,000 per year at age 62. The projections used had assumed a portfolio rate of return of 6 percent, and she was right on track for her goal. At the review, the performance shows a return far better than projected due to a strong bull market, and the portfolio yielded 20 percent. The investor is also growing weary of portfolio volatility as she approaches retirement. Luckily for her, she no longer needs a 6 percent rate of return to accomplish her goals. The projections show a 5 percent rate of return is all she needs. Given these circumstances, the investor may pull back her exposure to stocks and increase her exposure to bonds. She would be doing this knowing full well that the expected long-term rate of return will be less, but the probability of getting the 5 percent will have increased with less volatility in the portfolio.

The Ultimate Rule: Don't Mess It Up!

As seen on CNBC:

Host: So, is this a buying opportunity?

Guest: I wouldn't be a buyer of this market today (S&P at 1,740), but I would be a huge buyer at S&P 1,725.

This CNBC interaction illustrates precisely the wrong way to look at your portfolio. How can an allocation to stocks make no sense for an investor at S&P 1,740 but a lot of sense at 1,725?! Once you have the portfolio in place, stay disciplined. Follow the pattern of investment decisions outlined in this chapter or work with an advisor who understands, accepts, and invests with these principles. Ignore the noise, never panic, don't change plans in the middle of a crisis, and stay focused on your goals.

Portfolio Example

Common sense attests that some people can and do beat the market. It's not all chance. Many academics agree, but the method of beating the market, they say, is not to exercise superior clairvoyance but rather to assume greater risk. Risk, and risk alone, determines the degree to which returns will be above or below average.

—Burton G. Malkiel, A Random Walk Down Wall Street

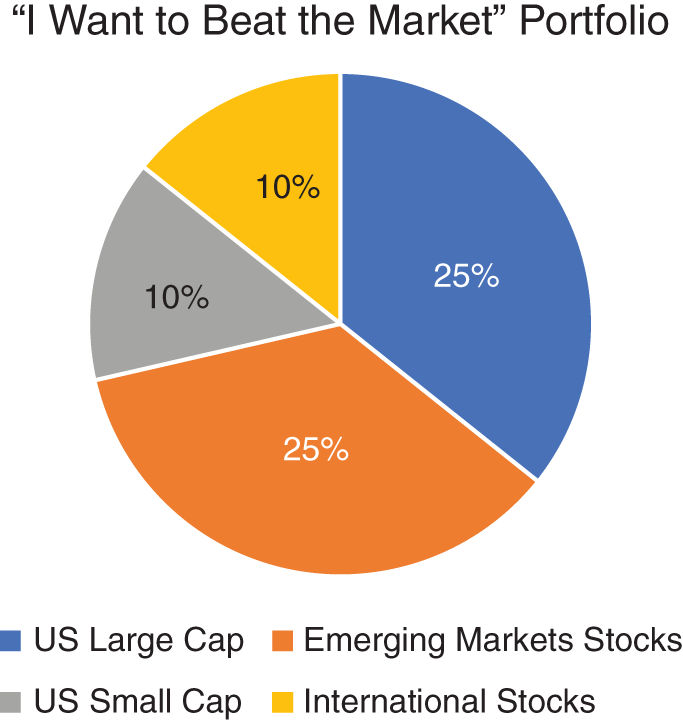

The “I Want to Beat the Market” Portfolio

This book explains why you can't beat the market by market timing or actively trading stocks. If you want to beat the market and define the market as the S&P 500, then the way to beat it over time is to increase the portfolio's exposure to asset classes that are likely to outperform large-cap U.S. stocks over long periods. Examples of such riskier asset classes are small U.S. stocks and emerging markets stocks. A “beat the market” portfolio may look like the one shown in Figure 6.4.

The “I Need 7 Percent to Hit My Long-Term Retirement Goal” Portfolio

A portfolio diversified across various asset classes and with a global approach has a reasonable probability of achieving the returns the typical investor requires. Such a portfolio may look like the one shown in Figure 6.5. Small-cap stocks tend to pull up returns over the long run, but the cost is long periods of underperformance. The U.S. tends to outperform or underperform international stocks, often for long periods. Keep this in mind during the rough periods!

The “Get Me What I Need for the Rest of My Life with the Least Volatility Possible” Portfolio

This portfolio should have enough stocks to pull the rate of return to where it needs to be over a long period, but enough bonds to allow the investor to take monthly or annual distributions without selling stocks in a down market. For an investor with $1,000,000 and who needs $50,000 per year, the portfolio may look like the one shown in Figure 6.6.

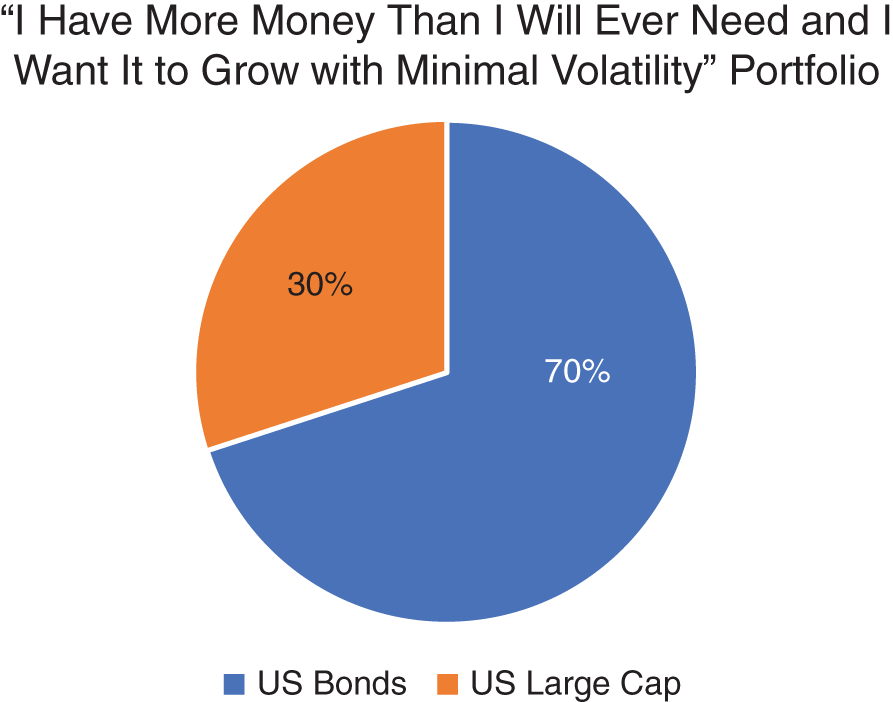

The “I Have More Money Than I Will Ever Need and I Want It to Grow with Minimal Volatility” Portfolio

This portfolio is for someone who has enough money that the income alone from stocks and bonds will meet their needs for life, even when adjusted for inflation. Despite reading this book, this person is fearful of stocks and wants a low-volatility portfolio that will allow her to draw about 3 percent without invading the principal (see Figure 6.7).

The “I Have More Money Than I Will Ever Need, Volatility Doesn't Bother Me, and I Want It to Grow Along with the Market” Portfolio

Some people are fortunate enough to have more investable assets than they could ever possibly spend. A subset of this group is not bothered by volatility, accepts that stocks will likely outperform bonds, and wants to participate in the market return, all without taking significant excess risk to try to beat the market return. For this group, a portfolio might look like the one shown in Figure 6.8.

A Path to Success: Intelligent Portfolio Construction

Some of the principles of portfolio construction are very straightforward:

- Avoid market timing; instead, invest for the long run.

- Avoid active trading; buy mostly passive investments.

- Don't fall for performance claims, get scared by the media, and the like; tune out the noise.

- Don't get in your own way; be aware of your behavioral biases, recognize them when they appear, and control them.

- Build a portfolio with asset classes that make sense for your situation.

For some, especially higher-net-worth investors, the portfolio construction can get more sophisticated. To match yourself to a portfolio that will not only accomplish your goals but that you can also live with, measure the return you need against the volatility you can handle. For good measure, make sure you consider taxes, as well as changing circumstances. While the portfolio itself should not be highly active, you must put more into it than simply choosing a few indexes and leaving it at that!

Notes

- 1 My wife disputes this statement.

- 2 Note that we will cover how to do this later, and it won't include market timing, actively trading, or voodoo. (No offense to those of you who practice voodoo. It probably is more effective than market timing or actively trading stocks.)

- 3 Also from Buffett, and much more entertaining: “Gold gets dug out of the ground in Africa, or someplace. Then we melt it down, dig another hole, bury it again, and pay people to stand around guarding it. It has no utility. Anyone watching from Mars would be scratching his head.”

- 4 Not one I would want to write, or you would want to read.

- 5 … and flushing it down the toilet.

- 6 I am always fascinated by those who want to rerun their plan monthly or quarterly. This is overkill and goes precisely against a core premise of this book, which is to have a disciplined, long-term outlook, making adjustments as needed. If you are meeting with an advisor who is making changes based on a quarterly review or outlook, it's time to get a new advisor. If you are updating your own plan every week online, it is time to find a new hobby.