CHAPTER

1

An Epidemic of Suffering

IT WAS JULY 24, 2013, a Wednesday. My husband, Tom, and I were at the hospital, sitting in a small, windowless nurse’s office before a desk laden with folders and papers. For years, I had worked in an office just like this one as a nurse administrator. But sitting here on this day was like no other experience I have ever had. This time, I wasn’t the nurse, conveying the results of a cancer biopsy. I was the patient.

Many nurses see death up close. And thanks to this proximity, some of us come to feel less afraid of it. Not me. Rationally, I knew that I probably didn’t have cancer. My doctor had told me that 80 percent of the time, the biopsies were benign for the kind of calcifications in my right breast—heterogeneous and BIRADS 4—that a routine screening mammogram had turned up. But frightening thoughts kept racing through my mind. What if I did have cancer? In that case, my life would change forever. I would be a cancer patient, a statistic. And the cancer might have spread to my bones or my brain. I might lose my hair from the chemo. I might die.

When I feel stressed, I don’t cry. I get quiet and withdraw into myself. That’s what I did here. “Well,” the nurse finally said, looking me in the eye, “It’s not what we had hoped for. You have cancer, both DCIS and invasive.” DCIS—or ductal carcinoma in situ—is a form of breast cancer that has not spread beyond the duct in the breast. But I had both: the noninvasive kind and the kind that could spread and kill you.

I felt numb. The nurse proceeded to tell me about my disease and the prognosis, but I couldn’t absorb any of it. I remained stoically silent, nodding my head at the appropriate times. Then, as my husband and I got up to go, the nurse complimented me on the gold bracelet I was wearing. When she said that, I began to sob. This piece of jewelry was very special to me: the year before, my husband had surprised me with it on Christmas. My husband held my hand as we walked out of the office and into the strange new world of cancer.

I wasn’t the only one who was terrified. Later that day, Tom broke down and cried for maybe the fourth time in 30 years. My daughters, my mother, my sister: All of them were worried. Nobody in our immediate family had ever had breast cancer. Would I be OK? Would I need chemo, radiation, or some other therapy? What would happen with my job? And what would it mean for my family, especially my sister and daughters? I was supposed to be the rock in the family—strong, brave, the person who had all the answers. Now I had more questions than answers. I was feeling incredibly vulnerable and out of control.

As anxious as we all were, it could have been a lot worse. Because I had a medical background, the language that my nurses and doctors were using was familiar to me. I knew exactly what questions to ask and how to perform medical research, so I wasn’t confused or uncertain about my treatment. I could convey my knowledge to the loved ones who worried about me. Imagine what people who don’t know much about medicine must go through. I was also extremely fortunate to have a secure job at Press Ganey, with a boss, colleagues, and an organization that went out of their way to show their support. When I told our president, Joe Greskoviak, of my diagnosis, he said to me, “Christy, I want you to know that this is when you focus on you. You are our CNO, and you will continue to be our CNO. Don’t worry about your job for another second.” I can’t tell you how much that relieved me, as did all the cards people sent me letting me know that they were thinking of me. Imagine what it must be like for the many patients who don’t have this support. These patients are not merely frightened about their medical diagnoses, but about everything in their lives that now seems at risk. We wonder as caregivers why our patients are often angry, sad, distant, and distressed. Now I knew: it’s scary to be a patient.

But my suffering as a breast cancer patient was by no means over. Once I had selected a surgeon who would remove the tumor, I had to undergo an MRI of both breasts so that we would know more about the scope of the surgery and the prognosis. The week after my biopsy, I found myself prone on an exam table and completely alone, save for a technologist on the other side of the MRI machinery. The MRI is loud and confining—equally scary for people who have never been in one and for those who know how they work and what they do. The preliminary results not only confirmed the cancer in my right breast; it showed four suspicious areas in the left breast as well. At this point, I was really scared. If the cancer was in both breasts, where else might it be? A follow-up ultrasound would provide some answers, but I had to wait two days for that. The waiting was excruciating. I just wanted the cancer out of me!

The ultrasound turned up nothing bad in the left breast, but I still had to decide whether to have a lumpectomy or a full mastectomy, and on one side or both. This was a very difficult decision for me. I had always thought that it wouldn’t bother me to lose both my breasts if I ever had cancer, but now I wasn’t so sure. When you have a lumpectomy, the breast is often misshapen but there is still breast tissue. When you have a mastectomy, all of your breast tissue is removed, including the nipple. You can have nipple-sparing surgery so that the surgeon can reattach your nipple after your mastectomy and during reconstruction, but the sensation is never the same. I talked with my family and my husband for hours trying to make this decision. And I had to think about all of this as I was still working hard at my job, dealing with my baseline anxiety about cancer, and trying to maintain some sense of normality for my family.

Other procedures leading up to my mastectomy brought torments big and small, some of which I’ll recount later in this book. Perhaps my greatest misery occurred after surgery. Awakening in the recovery room, I was taken to a shared room, where I would spend the night with another patient as my roommate. I was in a great deal of pain, so I pushed the call light to ask the nurse for medication. She said that I could have something in 20 minutes and that I should remind her. I was somewhat taken aback. I’m the patient, I thought, I have to remind you? I just had surgery. I can’t even think straight! My husband did remind her several times—still no pain medication.

I was hurting so much that I couldn’t sleep. It didn’t help that alarms were constantly going off, people were talking in the hallway just outside my room, and my roommate was shrieking with her own uncontrolled pain. Repeatedly I awoke thinking that an hour had passed, when it had only been a few minutes. I asked for earplugs, but the nurses didn’t have any. My husband found some in the gift shop, and they helped a little. But then a nursing assistant came in and said I had to get up to go to the bathroom. After she made the necessary preparations, I walked slowly over to the toilet. She seemed in a hurry and somewhat frazzled, so I asked her how many patients she had that night.

“Eleven,” she replied.

“How many does your nurse have?”

“Six.”

“That’s a lot,” I said, entering the bathroom.

She shrugged. “It isn’t that we have that many patients. It’s just that everybody is so needy tonight.”

That response confused me and made me feel a bit defensive. Did she mean me? I was trying not to be a pest or push my call light all the time. The last thing any patient wants is to be thought of as needy, especially a patient like me who also happens to be a nurse.

I happened to look down at that moment, and there on the toilet seat was blood—someone else’s. How could the staff on duty have simply left that there when they knew I was going to the bathroom? It was their idea for me to go to the bathroom in the first place! If they weren’t careful about keeping the bathroom clean for a scheduled visit, what else were they missing? The oversight didn’t inspire much confidence that I was in a place that provided safe, high-quality care.

I went back to bed and continued to struggle to sleep. Sometime later, the night nurse came in. Without bothering to introduce herself, she looked at my armband, adjusted my IV, and lifted my gown to check my dressing. Finally, I asked her: Who are you? Again, this oversight on her part undercut one of the hospital’s most basic functions: to help patients feel safe.

Morning finally came. I needed to get up, walk around, and stretch my legs. My husband helped me, holding me up by the elbow. I shuffled slowly around the unit. As we passed the nurse’s station, I spotted a number of people chatting with one another and tapping at their computers. After the comment about being “needy,” and after waiting endlessly for my pain medication, I was aggravated that they were all just sitting there. I knew that they were likely charting and reporting on patients to prepare for the next shift, but I still felt like I had gotten lost in the processes and paperwork. The people on the team hadn’t performed a bedside shift report (although I could hear them talking about me out in the hallway as they changed shifts). It would have been nice as a patient to have participated in the report and to hear their thoughts about my care and condition. Although many parts of my care had gone well, I couldn’t wait to get out of there.

Most caregivers don’t think much about the impact of seemingly “small” miscues like a dirty toilet seat, delays in bringing painkillers, or noisy patient rooms. What matters, we think, are the clinical outcomes. Cure a patient’s cancer, fix his or her fractured wrist, and you’ve done your job. This is horribly wrong. Clinical outcomes may be paramount, but the experience of healthcare is an outcome, too. When you’re a patient, miscues such as those I witnessed are not small. They make the difference between healing experiences and those so inconvenient or uncomfortable or painful or downright awful that you can’t wait to forget them. Of course, you can’t forget them. Like scars on your skin, they heal but never really go away.

The concept of suffering in healthcare is not new. The word “patient” itself derives from the Latin word for “to suffer.”1 Today, patients truly embody this ancient meaning, as people who seemed destined to suffer.2 Healthcare is seeing an epidemic of suffering, one that has only been increasing in recent years. You see it in every setting, from hospitals to clinics to doctors’ offices. Patients are suffering physical pain, and they’re tormented by emotions like anxiety, sadness, and loneliness. Rather than helping to ease this suffering, we in healthcare often worsen it. In too many cases, we’re actually causing it. We’re doing this not because we’re evil, incompetent, or lazy. The staff that took care of me, from the moment of my diagnosis to my surgery through to my recovery, weren’t trying to make my ordeal any worse than it had to be. And yet in a variety of ways, only some of which I’ve alluded to here, they were doing precisely that. Think about your own daily work. No doubt you show up every day trying to do your best. You work long hours, and you come home exhausted. But despite all that effort, are you sensitive to the suffering of your patients? Are you taking steps to ease it? Or are you, your team, your organization, and the industry as a whole serving unwittingly to worsen it?

Moving Past the Guilt

I say this not to lecture you from on high. Before getting sick myself, I had never really thought of my patients as suffering, either. I was caring for them, and they received great clinical care, so how could they be suffering? Yet they were. Early in my career, when I was working on a neuro step-down unit on the night shift, I cared for a woman in her thirties who had experienced a severe headache and lost consciousness. After giving her all the standard tests—blood work, CT scan, and an arteriogram of her brain to check blood flow—we discovered that she had had a subarachnoid hemorrhage from a cerebral aneurysm or weakness in the blood vessel. We had scheduled her for surgery the next day to fix the bubble in her blood vessel and reduce the risk of future bleeding. Brain surgery is very serious, and this woman had young children at home. I talked with her for about half an hour about what she could expect, and she described her fear of paralysis or a stroke during surgery. “I’m more worried about my family than anything,” she said. “I’m afraid for myself, but I’m more afraid for them.” I never thought of such fear as suffering, but of course it was precisely that.

This woman died on the operating table the next day. I have always asked myself what more I could have done to help her on that last night of her life. Could I have said something that might have eased her mind? Could I have attended better to her physical pain? Could I have listened better? Could I have been quicker handling her requests? Was there anything I could have done that would have made a difference? Thirty years later, I still think about this patient because I know she was suffering that night. She felt physical pain, she worried about herself and her family, and she was scared.

Why wasn’t I thinking about this woman’s suffering? And why do so few clinicians think of it today? I believe that the very word “suffering” makes clinicians feel guilty. We want to do right by our patients. And we feel that if our patients are suffering, we must be doing something to cause it, or we’re not doing something to relieve it. We also feel overwhelmed in our jobs—powerless to do much more than we currently are. So we would rather not talk about suffering. In the 2013 New England Journal of Medicine article “The Word That Shall Not Be Spoken,” Press Ganey’s chief medical officer Tom Lee wrote that “we avoid the word ‘suffering’ even though we know it is real for our patients because the idea of taking responsibility for it overwhelms us as individuals—and we are already overwhelmed by our other duties and obligations.”3We even go so far as to medicalize suffering as a psychiatric condition, “thereby transforming a moral category into a technical one.” British historians William F. Bynum and Roy Porter have pointed out that we try to treat suffering with medications, and we don’t pay attention to how we as caregivers contribute to it. “As a result, practitioners of biomedicine are in a situation unlike that of most other healers; they experience a therapeutic environment in which the traditional moral goals of healing have been replaced by narrow technical objectives.”4

To help improve healthcare for patients, Press Ganey began using the word “suffering” in 2012 in connection with its work concerning the patient experience. Tom Lee, who joined Press Ganey in 2013 as chief medical officer, observed that the word was so traditionally verboten in healthcare that had it ever appeared in an article in the New England Journal of Medicine, it meant that the proofreaders hadn’t caught it. He felt that we at Press Ganey had a role to play in bringing the needed change. I disagreed at first. Like so many others, I didn’t like speaking of “suffering,” and I asked that we use another word. Then I underwent my breast cancer treatment. Suddenly, everything I thought I knew appeared in a different light.

Defining Patient Suffering

My colleague at Press Ganey, Dr. Deirdre Mylod, postulated that we could distinguish between two kinds of suffering. The first kind, inherent suffering, is suffering that occurs inevitably as patients move through the healthcare system. The very diagnosis and treatment of a disease is guaranteed to cause a certain amount of suffering. Even if healthcare were perfect, the shock and uncertainty of a cancer diagnosis, and the physical and emotional discomfort associated with multiple diagnostic tests, surgeries, and treatments, would still exist. I know this firsthand. I suffered when I saw my husband cry upon learning of my diagnosis and when I saw the fear in my daughters’ eyes. We all suffered. When I wondered initially if I would be able to keep my job, whether we would be able to afford the necessary treatments, or whether my hair would fall out, I suffered some more. These worries were constantly on my mind. They were so pronounced that the stress caused physical pain in my back. No healthcare provider could fix this stress. It came with the diagnosis. Providers could help by reassuring me and giving me medicine, but they couldn’t take this suffering away entirely.

Do providers offer patients the help they need to ease inherent suffering? Quite often, we don’t. We’re slow with medication, or we provide insufficient pain relief. As one patient, in the study I described in the Introduction, told us, “I had difficulty with pain management and muscle spasms. This interfered with rest and recovery. I don’t know how else I could have communicated my needs for improved pain management. I felt the need was not met.” We must mitigate inherent suffering, knowing that we cannot eliminate it completely.

Avoidable suffering, meanwhile, is suffering that we as caregivers provoke or make worse because our systems are dysfunctional. Our actions give rise to avoidable suffering in a number of ways. When we leave patients waiting, we cause them to suffer. One respondent in our research related: “We had to wait nearly 1.5 hours to have a volunteer available to wheel me out—we were told 15 minutes.” Another said: “Just had to wait six hours to be admitted to a room. Bed wasn’t that comfortable while waiting.” Imagine that you were facing a potentially devastating diagnosis and that you had to wait for a diagnosis, a test result, surgery, or a procedure. Think of the fear of the unknown that you would experience. If you’re like many people, your mind would drift to worst-case scenarios in the absence of information. Your fight-or-flight response would kick in—your heart racing, your blood pressure rising, your pupils dilating. All you’d be able to think about would be the what-ifs. Every minute you wait would be a minute of extra suffering. It’s not just that you wouldn’t feel satisfied. You wouldn’t feel safe. There is simply no light between clinical quality, safety, and the patient experience. It’s all the same thing.

When we don’t provide clean and quiet environments, we erode a sense of safety and cause suffering. We sometimes think of cleanliness as providing a nice environment, but it is much more serious than this. When I walked into the bathroom and spotted blood on the toilet seat that was not my own, I was not just revolted—I lost faith in the people taking care of me. When an environment is clean, patients trust that they will not get an infection. Cleanliness is a bellwether for patient safety.

Similarly, keeping rooms quiet at night isn’t just a nice thing to do for patients. The literature is replete with evidence demonstrating the necessity of rest and sleep for healing. Caregivers must take care to assure that we are thinking about quiet in the same way that patients are. A large health system was struggling with its scores for the “quiet at night” survey question. Taking the issue seriously, the organization’s administrators and staff applied many best practice solutions. They fixed all the squeaky wheels on carts and beds. They installed devices in nurses’ stations that looked like traffic lights that would turn yellow and red when the noise in the area was too loud. Despite all this effort, the scores didn’t budge. Finally, administrators convened their patient-family advisory council and asked members what they were missing. The answer was astonishing. For patients, quiet had less to do with the absence of noise than with the absence of interruptions. Patients offered feedback like “You wake us up to take our vital signs”; “You come in to do stuff every half an hour rather than doing more things when you come in”; “You wake me up at 4 a.m. to take my blood.” Noise was important to control, but interruptions caused even more suffering.

Once administrators understood the true cause of suffering from the patients’ perspective, they could take action. The hospital worked with staff to consolidate activity in the rooms, making sure staff weren’t taking vital signs every four hours if it wasn’t medically necessary. The chief of staff went to the residents and said, “I know those 4 a.m. blood draws are important for you to get the information about the patient that you need. So from now on, if you order a 4 a.m. blood draw, call me to discuss.” Not surprisingly, those 4 a.m. blood draws were dramatically reduced. Once the hospital had made changes that mattered to patients, once it had reduced their suffering, the scores went up.

Another way that healthcare providers cause suffering is by treating patients without empathy. Healthcare providers sometimes talk about the need to be “nice.” What I’m talking about here isn’t being nice. It’s about showing courtesy and compassion. Talk to patients and their families. Encourage them to ask questions and make decisions about their care. Be gentle toward patients and sensitive to their needs. Ask yourself, How would I want to be treated? When the nursing assistant remarked to me that her patients were all “needy” that night, I didn’t feel respected. Instead of focusing on my recovery and future treatment, I became worried about what the staff thought of me. And I am certainly not alone in these feelings. As one patient in our study told us: “I had a good experience with all the nurses except one, and to this moment of discharge, I still feel that she was not fully professional and was judgmental in meeting with me.” Why should a patient fearing for her health and her future have to deal with a nurse who seems to judge the patient for whom she is supposed to care?

In addition, we cause suffering by failing to connect with patients. As a caregiver, everything you do and everything you say matters. You may not remember your patients or their families, but rest assured, they will remember you forever. That’s because you will have played a central role in one of the most frightening times of their lives. As we’ll discuss later in this book, when caregivers connect personally or emotionally with patients, it completely changes the experience for both parties. And when caregivers fail to connect, they leave patients feeling lonely, unimportant, and uncared for. Healthcare, after all, is a pretty intimate experience. If we were patients, we would never wish to have an intimate experience with a provider who didn’t try to find out a bit more about us as people apart from our needs as patients. Before someone touches us, performs a test on us, or sees us undressed, we would at least want to be acknowledged as fellow human beings who matter. Connecting with patients is as simple as understanding that the patient is a person with a family, a job, hobbies, friends, and a community who just happens to be a patient right now.

Healthcare providers also cause patients and their families to suffer when we don’t work well as a team. Uncoordinated care leads to repetitive and unnecessary interactions with patients that confuse and disturb them. One 2012 study of activities at an urban medical center found that up to 28 people—and up to 18 different people—entered patients’ rooms per hour.5 Nurses made the most visits, but medical staff made up 17 percent, with other clinical and nonclinical staff constituting 11 percent. During a typical, three-day hospital stay, a patient who was awake 12 hours per day interacted with up to 60 people. Imagine meeting that many people when you’re scared to death. How would you remember who they are, what they do, and why they’re doing what they’re doing? How would you be sure to follow all their instructions? You couldn’t and wouldn’t.

Clumsy or uncoordinated teamwork also erodes patient trust. When six different caregivers ask a patient the same question, the patient thinks either that we are inept or that we do not communicate with one another. They feel anxious about the people caring for them, and they suffer more. Healthcare is a team sport, and our patients need to know that we are all on their team communicating with each other about their care. Patients also need to know that their electronic medical records are accurate and that team members are using them well to coordinate the care they provide.

Of course, repetitive questioning often accrues not from poor teamwork but from a legitimate need to assure patient safety. Still, do we communicate that need to patients, framing the meaning of our interactions for them? Much of the time, we don’t—and patients suffer as a result. Think of the difference it would make if a caregiver offered a simple explanation like “Mrs. Smith, our most important goal while you’re in the hospital is to keep you safe, so you might hear us ask the same question multiple times in different ways. This is one of the ways that we make sure that we are keeping you safe.” Later in the book, I’ll present some other strategies that individual caregivers and teams can use to alleviate this kind of avoidable suffering.

Sometimes we use our team identity as an excuse not to treat patients as well as we might. We distinguish between “our” patients, and all those “other” patients who are not our immediate responsibility. When I worked as a nurse, I wanted to believe that my patients remembered that I was their nurse when they completed the surveys post-discharge. In truth, they might not have thought of it this way. When patients see a survey, “nurse” usually means everyone who took care of them, no matter what caregivers wore, how they introduced themselves, or what titles or other information appeared on their badges. From the standpoint of patient experience, we caregivers are all in this together. There is no “our patient” or “your patient.” Every patient in a bed, on a gurney, or in a waiting room is our patient and your patient. Just as the gate attendant at NASA helps put astronauts into space, so every person working in your organization is a caregiver responsible for every patient in that organization.

Caregiver Suffering

It might seem like I’ve been hard on caregivers so far by enumerating the many ways we cause suffering. It’s important to realize, however, that we caregivers ourselves experience suffering. Remember Kylie, the incredible ICU nurse my son-in-law, Aaron, encountered after he was shot? I asked her to come to the class I teach and to tell my students everything they needed to know to be just like her. She did come, and she confided that the work was hard—really hard. The hours, she said, were really long. Over time, the stress and exhaustion really wore on her. About a year after she took care of Aaron, I came across a message she had posted on Facebook. It read, “After working three jobs, driving more miles than I can count, and being away from my husband more than I ever want to be, I am officially retiring from nursing.” The long hours and stressful conditions had finally gotten to her. To this day, my heart grieves for the people Kylie would have cared for because she was such a wonderful nurse.

Kylie’s experience is hardly unique. Nurses and other healthcare providers typically work shifts that go long past 12 hours. New nurses and some seasoned nurses sometimes want 12-hour shifts because they think that will give them 4 days off every week. Also, many of us have martyr mentalities. We say things like, “That’s OK. I don’t need a break today,” or “We don’t have enough staff. I’ll skip lunch today.” I used to do this myself. I remember thinking that skipping lunch or breaks showed that I was tough and busy and irreplaceable for my patients and my colleagues. I was the first to step up and take open shifts and work overtime. Little did I know that I was exhausting myself and limiting my ability to maintain my compassion bank for my patients, my family, and myself.

When nurses work three 13- or 14-hour shifts back to back, with 6 hours of sleep and little to no life outside work during those days, they pay a price—and so do their patients. Studies have demonstrated that extended work shifts will result in more errors, adverse events, and complications. Yet almost every hospital and medical facility has personnel working 12-hour shifts that easily turn into 13- or 14-hour shifts.6 Consider a surgical technologist I happened to meet in the airport while traveling. I asked her if she worked 12-hour shifts, and she replied that she did. “Do you find that you are overly tired or make mistakes during those last four hours?” I asked. She told me that she really liked the 12-hour shifts, but that on the third day, she was, in truth, “not worth anything” at work. I certainly hope I’m not on the table on her third day!

Excessively long work shifts are only one source of caregiver suffering. Regulations, documentation, reimbursement pressure, physician and nurse shortages, patient complexity, and acuity are all facts of life for providers, and they all make connecting with the people who happen to be patients at the moment stressful and onerous. Over time, physicians, nurses, and other caregivers become overworked, exhausted, and unhappy. A job that had been fun, stimulating, and rewarding at first now causes daily suffering.

Consider a typical workday in the life of a nurse. She clocks in at 6:30 a.m. (or p.m.) and receives a report about how patients fared during the previous shift and what care patients will need. Ideally this report takes place at each patient’s bedside, so that the patient is involved. The process for that nurse’s patients takes at least an hour on a good day, longer if nurses have more or sicker patients for whom to care. The nurse must also assure that the patient care assistants (PCAs) also know patient needs, and the nurse must handle new orders from physicians that come in unpredictably as they make their rounds. Often, the patient knows more about the care plan than the nurse does, simply because the nurse couldn’t join every physician on his or her rounds. Nurses have much to do: they must administer medications, change dressings, educate patients and families, transfer patients to diagnostic testing, and admit patients from ICUs, the emergency department, surgery, or elsewhere. Admissions and discharges typically take about half an hour, sometimes longer, as the nurse obtains detailed information about the patient’s health, illness, medications, and history; assesses the patient from head to toe; and receives orders from the admitting physician. And all of this has to be documented.

Discharges also take time. Nurses must convey discharge instructions clearly so that patients will be safe and successful upon leaving the hospital. If patients require follow-up care, nurses must help them make appointments, locate equipment, or reserve rooms for skilled nursing or long-term care. In some busy units, every bed in every room might turn over during a 24-hour period, with an existing patient being discharged and a new one being admitted. This means that during a given shift, a nurse who normally cares for four to six patients might admit or discharge twice that number. Although many budgets are based on a midnight census (i.e., the number of “heads in beds” at midnight), the true amount of patient turnover and the true amount of work involved might be much higher. And of course, all of this doesn’t include the task of documenting patient care. In a perfect world, nurses will perform documentation at the patient’s bedside, but they often don’t have the time. In these instances, they must perform documentation after their shift is over, leading to overtime and extended work shifts. Often nurses are so busy throughout their day that they don’t even have time to leave the unit in order to eat lunch or grab a quick coffee. And tomorrow, they have to get up and do this all over again.

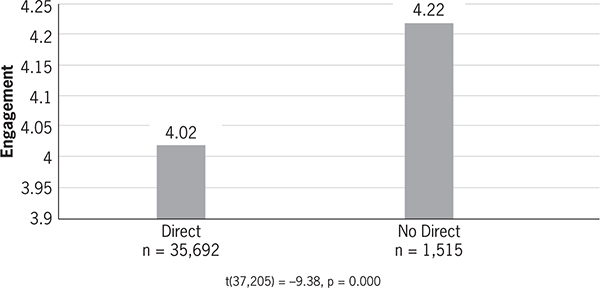

Every nurse’s job is different—the scenario I’ve provided here is just a general sketch. But make no mistake—the caregiver suffering that results from a typical caregiver’s job is real. You see it indirectly in the high rates of nurse turnover and engagement. A Becker’s Hospital Review infographic from 2016 put the one-year turnover rate among all newly licensed RNs at 17.5 percent and the two-year turnover rate at 33.5 percent.7 Citing other research, my colleague Dr. Barbara Reilly and I observed in the Online Journal of Issues in Nursing (OJIN) in 2016 that 15 out of every 100 nurses are disengaged based on the performance of nurse employees at one standard deviation below the mean in the largest healthcare employee engagement database.8 “Conservative estimates suggest,” we said, “that each disengaged nurse costs an organization $22,200 in lost revenue as a result of lack of productivity. For a hospital with 100 nurses, that equates to $333,000 per year in lost productivity. For a large system with 15,000 nurses, the potential loss skyrockets to $50 million.” When we think about a lack of productivity, we might think of not working to our full capacity or not accomplishing as much as others. However, a lack of productivity can also manifest as a lack of teamwork, constant grumbling, poor attitudes, and absenteeism. Further, what we often attribute to staffing issues may in fact result from low engagement levels.

Retention of experienced nurses is also a significant issue leading to a perpetual cycle of lost productivity, lack of engagement, and turnover (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2). As we wrote in OJIN, the “National Healthcare Retention and RN Staffing Report” identified a 16.4 percent average turnover rate for nurses in 2014. The conservative estimate of the cost of turnover was listed at somewhere between $36,900 and $57,300. When you do the math, that means billions of dollars in nursing turnover costs alone.

Figure 1.1 RN engagement by direct patient care

Figure 1.2 RN engagement by tenure

Press Ganey data show that nurses score higher on the engagement scale, averaging 4.11 on a scale of 0–5. But while that may seem like good news, it has a dark side. The nurses that are most engaged are those that have only been with the organizations for less than six months. In other words, those with the least experience are the most engaged. Get more experience, and you become disillusioned with your job. Even worse, the data show that the further a nurse moves from the bedside, the more engaged that nurse is. The people at bedside are often the least engaged. How are we to engage patients if the people who are caring for them are not engaged?

Nurses, like all other caregivers, want to provide optimal care, and it’s difficult when they know they’re not in a position to do it because of the processes, systems, and general work conditions that exist in their organizations. So they become disillusioned with their jobs and lose motivation to perform. They suffer.

High turnover due to caregiver suffering in turn directly impacts the performance of healthcare organizations. Many units facing staffing shortfalls require nurses to come in on their off days, and many hire traveling nurses to care for patients. Unfortunately, traveling nurses are at best an imperfect solution. Since they earn more, morale among permanent nurses sags when traveling nurses come on the job, and traveling nurses often don’t feel the same levels of accountability and commitment. Over time, organizations sink into mediocrity. Lack of engagement by the nurses who remain on staff also proves costly to organizations, causing declines in the quality of care.

When speaking of caregiver suffering, we should distinguish between inherent and avoidable suffering, just as we did for patients. One might argue that in any profession or job, workplace conditions will cause a certain amount of suffering. Trial lawyers must deal with deadlines and the stress of courtroom appearances. Elementary school teachers must deal with the fatigue that comes with trying to corral six-year-olds for the better part of a day. Likewise, the basic conditions of healthcare cause a certain amount of suffering for caregivers. Healthcare is incredibly complex, and it’s changing almost by the minute. Patients are very sick, and they sometimes die. Technology is exploding, and caregivers are expected to understand how to use it appropriately. These conditions cause stress for caregivers that is simply part of the job. Even if healthcare were perfect, this kind of caregiver suffering would persist. However, as I’ve suggested, caregivers also suffer a great deal of avoidable suffering—not just from overscheduling but from lack of trust in leadership, lack of respect shown by organizations, bullying by colleagues, verbal and physical abuse by patients and visitors, and lack of safe refuge for reporting. The causes of avoidable suffering are many, and organizations must address them if they are to improve both the caregiver experience and organizational performance.

Answers to Suffering

My struggle with breast cancer woke me up to a reality that had been around me all along but that I hadn’t understood: the reality of suffering. We in healthcare don’t like to think about it, but we’re failing to alleviate the inherent suffering that patients feel, and we’re also causing an incredible amount of avoidable suffering. Meanwhile, we’re in pain, too, consigned to jobs that are exhausting, stressful, and all-too-often devoid of the fulfillment we expected when we left school and took our first healthcare jobs. Suffering represents a hidden plague that afflicts virtually everyone in healthcare. We talk about “patient satisfaction” or “employee satisfaction,” and we think that this suffices to capture the way people experience healthcare environments. It doesn’t. Whether we like it or not, suffering is real, and we need to deal with it. We can’t satisfy ourselves with delivering excellent clinical care. As a cancer patient, I took clinical excellence for granted. It was the compassion and connectedness with caregivers that I needed, the absence of which created suffering for me. The care I received saved my life, and for that I was and remain profoundly grateful. Yet the elements of my care that weren’t right left a scar every bit as real as the ones on my chest. No patient should suffer such scars more than absolutely necessary.

Much of the time, we have it in our power to alleviate suffering. Later in this book, I’ll provide many solutions to this problem that are readily available to us. But we also need the will to carry them out. Sometimes that will exists. A few days after my breast surgery, I called the president of the hospital where I’d received treatment as well as the director of service excellence. I told them everything about my experience and the suffering I’d felt. To their credit, they invited me to come and describe my experience to members of their patient and family advisory board, which was composed of both internal staff and community members. Several weeks later, I met with the board and found its members eager to hear my story and to correct the issues presented. I commend them for that, and I hope that administrators and boards everywhere demonstrate the same zeal to improve what they do and reduce the suffering that patients and caregivers experience.

To address suffering, we ultimately must get back in touch with our purpose as healthcare providers—why it is that we got into this business to begin with. We need to remember that we’re here to serve patients and help them to heal. But it also helps to understand just a bit about why suffering has become such a problem in healthcare today. As my analysis so far has suggested, the vast majority of suffering doesn’t result from “bad” or unfeeling caregivers, but from systemic factors that limit how we approach and perform our jobs. It is to this topic we now turn.