CHAPTER

6

Compassionate Connected Teams

DURING THE EARLY 1990s, I had an unusual opportunity to observe and study up close the functioning of teams in healthcare. I was working as a nurse in the PACU of Wickerland Health Center (not its real name), a large, level 1 trauma center in the Midwest. At the time, healthcare organizations across the country were moving toward universal, “managed care” as part of Hillary Rodham Clinton’s reform efforts. Buying up physician practices, organizations hoped to integrate care and render it more efficient. Under this new model, primary care physicians would serve as “gatekeepers” for patients, helping them navigate the many specialties and subspecialties now located under one organizational roof. Organizations were worried that healthcare reform might lead to lower reimbursement, so they were working preemptively to reduce the cost of healthcare and improve access to care.1 At Wickerland, administrators had brought in consultants to redesign the hospital’s surgical services so as to reduce waste and cut costs. Administrators needed someone to serve as the liaison between the consulting firm and the hospital, and they asked me if I’d like the job. I wasn’t quite sure what I was getting myself into, but I liked the challenge, so I agreed to take it.

Wickerland had 26 operating rooms at two locations inside the hospital. We performed scheduling tasks the old-fashioned way, using a paper scheduling log to keep track of both surgical cases and staff schedules. Since we only had a few operating rooms dedicated to specialties, such as heart/vascular or lithotripsy, we tended to allocate space on a first-come, first-served basis. In a given operating room, we might have booked a tonsillectomy, then a hernia repair, and then a total joint replacement, moving staff between rooms to assure that we assigned them cases in which they had the requisite experience and expertise. The system was chaotic and fraught with delays, leading to problems with staffing and overtime. Staff never knew where they would be working or with whom, so they became stressed and frustrated. Surgeons were forced to wait around between cases, but they couldn’t leave the hospital because they didn’t know if a room would open up and they’d have to go to work. Patients had to wait for long periods, and they often had their surgeries canceled or moved. The hospital was making money, but it certainly wasn’t maximizing its margins.

To push ahead our reform efforts, we established cross-disciplinary task forces to handle each of the primary projects: staffing, materials management, OR scheduling, and information technology. A steering committee oversaw the work, setting rules for the task forces to follow based on requirements dictated by hospital leadership. Operating within these rules, the task forces conducted research and came up with specific recommendations for reform. Only when the steering committee had approved these recommendations and leadership had signed off would the hospital implement them. The real power lay with the task forces. The steering committee had agreed to support task force recommendations, provided that they stayed within established guidelines and that hospital administrators served on the steering committee. So as our task forces got to work rethinking how we would organize the OR, we felt confident that we would be able to effect real change.

After some initial difficulties that I’ll describe a bit later, we did manage to transform the OR. Over a six-year period, we implemented a number of recommendations that our task forces had generated, including block scheduling of the OR, the reduction of instruments in our surgical instrument sets, and strategic reductions in staff hours. We held weekly team meetings to review data and make adjustments in our strategy, monitoring a number of metrics, including block time utilization, on-time starts, scheduling, and staffing relative to expertise and aptitude. We started self-scheduling and convened teams that reviewed elements such as surgeon preference lists and room stock. At all times, we worked collaboratively and communicated transparently, taking care to include representatives from the OR staff.

The results exceeded our expectations. Surgical cases increased by over 5 percent, while the number of operating rooms necessary for surgical cases on weekday afternoons and evenings declined by 45 percent. Thanks to the increased efficiency, we boosted revenues to the general/trauma surgeon group by more than 6 percent. Because we also enabled the nursing floors to predict their evening and night-shift staffing requirements more accurately, we reduced overtime by 2 percent. Caregiver suffering declined, as evidenced by improvements in “staff morale and retention.” Our improvements were so dramatic that industry experts cited us as models for scheduling, team-based care, on-time starts, and overall flow.2 We took an average OR and put it on the map!

The experience of redesigning the OR at Wickerland taught me a great deal about teamwork and its relationship with suffering. Poor organization of our surgical teams had been causing considerable suffering for our caregivers and our patients. Staff often couldn’t work in the specialties they wanted and in which they were most skilled. Surgeons had to deal with expensive gaps in their schedules, as well as incomplete instrument sets. Patients and families underwent long waits. But by coming together across disciplinary boundaries as cohesive teams, we had been able to redesign our operations so that our operating teams could work better. Within each redesign team, colleagues shared information and discussed our current practices, best practices at other organizations, our goals for the future, and what it would take to realize them. Our final recommendations improved scheduling accuracy and on-time starts, reduced case duration and turnover time between cases, and improved staff and physician engagement. Patients waited less and received higher-quality care. Staff and physicians enjoyed their jobs more. All of us suffered less.

To reduce suffering under the Compassionate Connected Care model, it’s not enough for individual caregivers to embrace the right kinds of behaviors. We also must support Compassionate Connected Care through teamwork, on two distinct levels. First, we must improve the way teams operate in general. Disorganized teams fragment the provision of healthcare, leading to a host of issues for patient and caregiver experience. We can have the world’s most compassionate and connected caregivers, but we’ll never reduce suffering in meaningful ways unless teams at healthcare organizations also operate at optimum levels. On top of this, patient-facing teams in particular can take specific steps when interacting with patients to make connections and improve their experience. By focusing on both levels at once, we can support the good work that individual caregivers do to reduce suffering, solidifying our gains in the patient and caregiver experience.

The Value of a Good Team

Before examining how to reduce suffering by improving team performance generally, let’s first review the kinds of teams that commonly exist in healthcare settings and the impact these teams have on patient experience. In a 2012 discussion paper, the Institute of Medicine defined team-based healthcare as “the provision of health services to individuals, families, and/or their communities by at least two health providers who work collaboratively with patients and their caregivers—to the extent preferred by each patient—to accomplish shared goals within and across settings to achieve coordinated, high-quality care.”3 The authors go on to report that “in order to benefit from the detailed information and specific knowledge needed for his or her healthcare, the typical Medicare beneficiary visits two primary care clinicians and five specialists per year, as well as providers of diagnostic, pharmacy, and other services.”4 But groups dedicated to caring for patients aren’t the only kind of interprofessional or cross-disciplinary teams that exist in healthcare. Organizations also bring caregivers and staff together as “project teams” to address operational issues, as we did at Wickerland. If organizations are to improve experience and reduce suffering, it’s critical that both kinds of teams function well, with fluid coordination, collaboration, and communication taking place among all team members.5

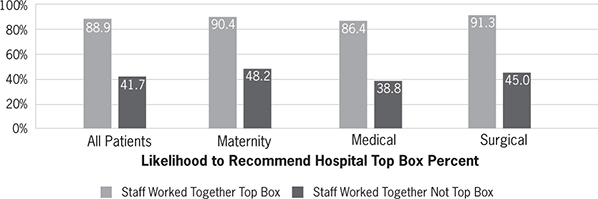

Our research shows that patients intuitively perceive a connection between teamwork and the suffering they experience. As we saw in Chapter 3, strong teamwork helps patients feel safe, loyal, and cared for. In particular, patients’ perceptions of the coordination of care within hospitals, measured by the survey item “How well staff worked together to care for you,” strongly influence whether patients recommend the hospital across service lines, including both inpatient and ambulatory care. Patients who ranked staff the highest for their ability to collaborate were far more likely to recommend a hospital than patients who gave staff lower marks for working together (see Figure 6.1). Caregivers also recognize teamwork’s relevance for reducing their own suffering. As I recounted in Chapter 4, I asked a group of 500 clinicians to rank the six themes of Compassionate Connected Care for the Caregiver. They ranked teamwork the highest by double-digit percentages.

Figure 6.1 Impact of staff teamwork on HCAHPS “likelihood to recommend”

Such patient and caregiver impressions are not hard to understand. In sports, a lack of communication, accountability, and preparation by teams causes them to lose games. In healthcare, the consequences of poor teamwork are potentially much more severe. When teams function poorly, care becomes fragmented, leading to at least some amount of suffering in the form of duplication of care, patient confusion, and so on. As quality deteriorates, patients and their families suffer even more due to potential medical errors, adverse events, complications, and readmissions. Even when a world-class care team delivers high-quality care, patients and families will never rate the care they received as excellent if the patient is harmed in the process. A growing body of research has uncovered meaningful links between clinical safety, the effectiveness of healthcare, and patient experience.6

Unfortunately, teamwork often breaks down in healthcare organizations today. More than one-fifth of U.S. hospital patients reported system problems, including the provision of conflicting information by staff and the inability of staff to tell them which physician was taking charge of their care.7 When poor teamwork impinges on the patient experience, caregivers often don’t realize it. Some analyses find vast disparities between physician and patient perceptions of teamwork. At one facility, patients ranked teamwork at the 67.9th percentile, while physicians at the same facility ranked it at the 97.5th percentile (see Table 6.1).8 That’s a huge difference! Clearly, we must do better at educating all caregivers (not merely physicians) about how to function well on teams, and also about the specific components of teamwork that matter most to patients. But how exactly should we do this? If our goal is to reduce suffering, how might we best focus to attack the difficult problem of improving teamwork?

Table 6.1 Patient and Physician Rankings of Teamwork at a Healthcare Facility

Optimizing Teams

According to organizational behaviorists Anna Mayo and Anita Williams Woolley, strong teams “can aggregate, modify, combine, and apply a greater amount and variety of knowledge” in the service of decision making, problem solving, idea generation, and task execution better than any one individual could do alone.9 But as these scholars also attest, putting a bunch of smart people together and calling them a team does not make them one. Press Ganey chief medical officer Tom Lee agrees, distinguishing between pickup teams that form casually on playground basketball courts and professional teams. Pit a pickup basketball team against the Cleveland Cavaliers, and even if the individual members of the pickup team are as talented as those on the Cavaliers, the pickup team will lose every time. Why? Because the pickup team isn’t truly a team. It’s just a group of people who share a common interest in playing basketball. The Cavs, and every other NBA team for that matter, are made up of highly experienced experts who constantly train and study their craft together and who are motivated to excel as a group rather than just as individual players. Each Cavs player not only commits to the group but is accountable to it for his own play and preparation. The team “owns” the game. Team members win or lose together, which is why losing is never an outcome they readily accept.

When it comes to reducing suffering, the question thus becomes, how might we best transform groups of healthcare providers into genuine teams capable of delivering on patient experience? For starters, we should focus on improving leadership. All teams in healthcare, both patient care and project teams, need strong leaders—visionaries who can define a common purpose, inspire confidence, promote skill building, recruit team members with the right skills, remove issues that might prevent the group from performing, and work side-by-side with staff.10 All too often, such leadership doesn’t exist, if only because organizations form teams haphazardly. When a hospital convenes a group of people who have the same interests and says, “Your goal is patient care,” it’s a pickup team. When we hire based on the strengths that we need for the team, provide a vision that the team can not only buy into but truly own, and help team members navigate through conflicts when they first begin working together, then we have real teams that can accomplish great things in patient experience, safety, clinical quality, and staff engagement.

Certain areas of leadership seem ripe for improvement on healthcare teams. Leaders in any context must promote psychological well-being, creating safe climates that facilitate learning. Team members will more likely take risks when leaders give each of them an equal voice and when they trust that leaders will support them even if they fail. When leaders themselves push change by monitoring their environment, identifying processes or behaviors that require change, and coordinating change efforts, team members feel even more comfortable proposing new ideas.11 In too many cases, leaders don’t invite team members to participate, and they don’t proffer support. Rather than seeking change, they seem to resist it. As a result, teams go adrift and fail to take steps that would reduce suffering and improve the patient experience. Organizations embark on ambitious patient experience initiatives, but come away with little to show for them.

The Wickerland perioperative steering committee I mentioned earlier was a case in point. After our task forces delivered their recommendations and the steering committee approved them, hospital leadership was supposed to implement them in due course. That’s not what happened. The task force on OR staffing recommended that the hospital cut back on surgical staff. But it also recommended that the hospital provide more patient care assistants or environmental services personnel for room cleaning, turnover between cases, and transport. Another task force examined the number of instruments contained in each instrument set and gained consensus from surgeons on what was critical to maintain in these sets (no small accomplishment). This task force recommended that the hospital could place fewer instruments in the instrument sets, but only if the hospital made more instruments available as “separates” on an individual basis. The OR scheduling task force recommended that the hospital streamline operating rooms by scheduling time in blocks. But it also recommended that the hospital leave 25 percent of staffed surgical time “open” or unblocked to accommodate unscheduled or add-on cases.

All these recommendations passed the steering committee. However, when it came time for hospital administrators to implement the recommendations, they did so selectively, breaking with the procedural rules that they themselves had set. Administrators agreed to fewer staff in the OR, but they refused to commit to providing additional patient care assistants. If at some later date the data demonstrated that we needed more of these assistants, the hospital leaders said they would provide them then. Administrators likewise agreed to fewer instruments in the instrument sets, but they declined to provide more single instrument separates. They would provide those “if needed.” Finally, administrators agreed to the block scheduling, but they refused to allow for open time in the schedule.

Keep in mind, the task forces had collaborated closely for months. They had performed time and motion studies, examined endless amounts of data, and surveyed the people who did the work, including surgeons, surgical technologists, circulating nurses, and other personnel. They had evaluated the data together and deliberated as a group to arrive at their recommendations. Hospital administration didn’t take any of this into account. They violated the rules of our redesign process, leaving the staff to do the same work with fewer employees in each room, fewer instruments in the sets, and no flexibility in the schedule. The last of these led to more “add-on” cases that went late into the night.

Staff members were frustrated, and they soon decided that they weren’t going to take it anymore. Months after working in these frustrating conditions, every single member of the operating room staff walked out. Administrators rushed to bring in replacement staff from the organization’s sister hospitals, but that wasn’t enough to prevent surgical cancellations. The walkout lasted three days, ending when leaders agreed to a series of demands, including more staff input into decisions and a review of policies and procedures. Three administrators lost their jobs, including the CEO. My job wasn’t at risk, but I thought about leaving anyway. I suspected that staff and physicians would lump me in with leadership, blaming me for the way that their recommendations had been undermined. Happily, my fears were misplaced. The staff sent me flowers, saying they knew it wasn’t my fault. They asked me to stay, and I did.

When leaders at Wickerland didn’t fully accept the recommendations even after the work hewed to the requirements that leadership itself had set, any semblance of psychological safety evaporated. Nobody felt comfortable addressing issues openly. Although the people in management had invited collaboration, their actions suggested that it had all been a sham—they were calling the shots, and full participation by other stakeholders wasn’t welcome. No wonder staff members abandoned the process and walked out. To address suffering, leaders should create conditions for psychological safety and refrain from taking actions that compromise it. First and foremost, they should set clear guidelines for inclusive participation and stick with the rules, even if the results aren’t entirely to their liking. Let our experience at Wickerland stand as a cautionary tale.

Another important leadership area to address in order to improve teamwork in general is recruiting. When the National Football League holds its annual draft, teams arrive with specific needs, and they attempt to draft players who will best fit those needs. Teams in healthcare must do the same. In particular, they must do a better job of making sure that they contain representatives of all the disciplines that care for patients. Research has repeatedly shown the benefits of teams that integrate direct caregivers into the mix and that are comprehensive (for instance, including pharmacists, not just prescribing physicians, in the management of medication). Such teams help forge alliances among providers, patients, and families,12 serve patients’ needs better,13 and leave them feeling supported,14 with better quality care. As a result, suffering decreases.

After the consultants left Wickerland and the staff ended its walkout, we developed a robust Perioperative Services Guidance Committee. This committee reviewed all the prior recommendations from our task force teams, evaluating whether and how to implement each one and promulgating policies to implement approved recommendations. We recruited for this committee thoughtfully, including leaders in each surgical specialty, the chair of anesthesia, the nurse managers of each of the areas of perioperative services (OR, PACU, preop, ambulatory surgery), the manager of materials management, and the VP responsible for perioperative services. The committee was cochaired by the director of perioperative services and the OR’s medical director, and it was small enough to make decisions quickly (as research shows, small groups tend to perform better than larger ones).15 The group had a “checkwriter,” a person authorized to make decisions so that we didn’t have to obtain additional approvals at every turn. The group also included leaders who embraced change and continuous improvement. Their energy and enthusiasm allowed us to make rapid progress, correct for errors along the way, and achieve our goals.

Leaders can also improve teamwork—and help reduce suffering—by improving how they manage teams day to day. So often leaders don’t empower team members to take ownership over their results. They dictate solutions, trying to solve problems themselves, without drawing on the team’s talents. To work together more effectively, we must push authority—and responsibility—downward to team members themselves. This isn’t easy, but with determination and focus, it can be done.

When I became the director of perioperative services, one especially vocal trauma surgeon on our team never hesitated to let me know when a case didn’t run smoothly. He was almost always right, but his domineering style undercut his message. I counseled him about this, and we finally agreed to “Christy’s rule,” a stepwise process for addressing problems and changing our processes. Christy’s rule was the following:

1. If you brought a problem to management (me), I would do what I could to address it.

2. If I couldn’t address it and the problem persisted, the person who brought the problem to management would join a committee to address the problem. If a committee did not yet exist, that person would cochair a new committee with me.

3. If the person who brought the problem didn’t want to help resolve the problem, he or she could no longer raise the issue.

This “rule” gave team members more ownership over work processes in our operating rooms. If issues arose, they were no longer “someone else’s problem.” We all owned what happened in the OR for our patients and staff. When staff members grew concerned about how we scheduled holidays, we laid down clear guidelines (for instance, we specified that staff members couldn’t have the same holidays off every year, that all cases must be staffed, and so on) and then convened a staff team to come up with a policy. Team members arrived at a great policy, and they owned it. Similarly, when surgeons approached me and said they needed us to assign them staff members who always knew their routines so that cases would go smoothly, a team of staff and surgeons convened to determine what a “team” looked like for each specialty. This work reduced the time required to complete cases, increasing staff satisfaction and engagement and reducing suffering for patients (as our data show, higher staff engagement translates directly into better patient experience).

One reason the Perioperative Services Guidance Committee succeeded was that it also gave strong ownership to team members. The committee approved of and often developed policies related to the operations of perioperative services. For example, it developed a detailed on-time start policy for the OR. The data were collected and shared weekly with the committee, and penalties were established for surgeons who started their blocks late more than 10 percent of the time. The committee agreed that surgeons who violated this policy would not be able to start before 9 a.m. (7:30 a.m. was the first case start time) and that their blocks could not extend longer because of a late start. This policy was a big deal, and it helped improve our on-time start rate from only 30 percent to 90 percent, reducing overtime pay, delays, and cancellations. The policy succeeded because it was developed by the committee, enforced by the committee, and continuously evaluated by the committee. The committee was a team, and each member of the team had an equal vote, regardless of his or her role or title. Each member brought unique insight and experience to the committee, and the committee relied on these strengths during its deliberations. Although the committee had its growing pains, it gelled during its first six months together and went on to perform exceptionally well. Patients and caregivers suffered less as a result.

Besides empowering team members, leaders can help their teams run more smoothly and get vastly more done by improving how they run meetings. In my work with organizations across the country, I have heard many physicians lament that they no longer participate in meetings “because nothing ever happens.” Meetings are an investment in time and effort, and when they fail to produce results, people become disengaged. In many cases, the culprit is “analysis paralysis.” We in healthcare have more data than ever before, and many teams just don’t know what to do with all this information. So we study it. And study it. And study it. We talk about the data and the issues, but we fail to take action.

For teams to function properly, meetings must be efficient and purposeful and be scheduled appropriately. When forming our Perioperative Services Guidance Committee, we knew the committee wouldn’t function properly if it held monthly meetings. So we held weekly meetings, and to assure maximum attendance, we scheduled these meetings at 6:30 in the morning to fit the needs of surgeons and anesthesiologists. In many cases, the team met for 30 minutes and sometimes an hour. Participation in the meetings was mandatory, but rarely did anyone want to miss a meeting because we made decisions at every meeting. We shared data so that we could evaluate how well the policies we had adopted were functioning, but we didn’t overanalyze the data. We stuck to a clear agenda, which called for taking action and making progress. At the end of each meeting, we specified actions that team members would take, as well as deadlines for achievement. At the following team meeting, we reviewed progress since the previous meeting, holding team members accountable for their results.

Properly organized meetings can yield amazing results that significantly reduce suffering, and they can do it quickly and efficiently even when teams are quite large. I witnessed a good example of this firsthand when I observed the real-time demand capacity team at a large academic medical center.16 Committed to streamlining the patient discharge process, the team held daily meetings at 10 a.m., gathering representatives from every area of the organization into a large meeting room. This group included people from the OR, ED, inpatient units, EVS, imaging, patient access, facilities, food service, administration, transport, and others. Their goal was to increase the number of patients discharged by 2 p.m. The more patients the hospital discharged, the fewer delays other patients would experience as they were admitted from the emergency department, the operating room, the intensive care unit, or the hospital clinics. By fixing the discharge process, the hospital could significantly reduce suffering due to wait times that patients might have regarded as interminable—and that could, in fact, compromise their care.

The real-time demand capacity team met daily—appropriate scheduling given the team’s desire to increase discharges rapidly. The team kicked off each meeting with a review of its success the day before. How accurate was the team in predicting which patients would be discharged by 2 p.m.? Team members discussed why some of their predictions had not panned out and what they would need to do to overcome barriers going forward. Then the representatives of the individual units discussed what was occurring within their units, how many available beds they had, and how many people they thought would be discharged and could leave by 2 p.m. More important, each unit identified the obstacles team members were encountering.

For example, one manager alerted radiology that a certain patient was simply waiting for a chest x-ray before he or she could leave. Noting that information, the radiology representative made this patient a priority in order to get the patient discharged without an excessive wait for a follow-up test. In another instance, a manager stated that a room of hers was out of service because of a broken call light. The facilities representative made sure it was fixed immediately. In this way, daily interprofessional team meetings assured that the people who could make things happen were all in the same place to address the issues immediately, without multiple phone calls or approvals. The improved communication streamlined the discharge process, making it more predictable and less chaotic for caregivers and patients alike. Patients could better arrange for rides home, and they could prepare emotionally to leave the hospital. Better discharge processes, in turn, improved the admissions process, as staff could predict better when beds would come open for other patients. Improved communications also enhanced staff members’ collegiality. When they convened each day, they could solve problems as they occurred, rather than allowing them to fester. They could devise meaningful solutions, not merely a series of disconnected work-arounds.

Optimizing Patient-Centered Teams

In addition to improving teamwork generally, organizations can reduce suffering by taking more specific steps to enhance how patient-facing teams operate. These steps include:

Improving Team Huddles

In his book Mastering the Rockefeller Habits (2002),17 Verne Harnish advised companies to hold daily, short meetings in which the team stands or “huddles” together to address questions and issues. The point of such meetings was to keep goals well aligned and to allow teams an opportunity to address issues quickly and hold team members more closely accountable. In healthcare, many patient-centered teams have come to implement huddles to discuss relevant issues, make a plan, and follow up on whatever happened at the previous day’s huddle. The problem is that patient-centered teams often don’t perform these huddles consistently or well. As a result, teams don’t function as well as they might, with caregivers and patients paying the price.

Once, while visiting a healthcare organization, I had a chance to follow a nurse manager who led a unit that was achieving mediocre results. I asked her if she held huddles, and she said that she did so “sometimes.” When I inquired about how staff received information, she said that she sent out a monthly newsletter. On other occasions, managers have told me that they communicate via e-mail, Twitter, and text messaging in lieu of huddling. All of these are wonderful forms of communication, but they lack something critically important that huddling provides: a chance for real-time dialogue. To achieve sustainable results, you have to talk through challenges, discuss the data, and arrive at consensual solutions. Simply pushing out information does not assure that people understand and act upon the information to improve patient care.

In healthcare, huddles frequently work better than conventional meetings that last longer and are held less frequently. In 2013, Advocate Healthcare did away with its usual team meetings, replacing them with frequent 15-minute team huddles. Good thing: the number of safety issues uncovered by teams jumped 40 percent. By meeting daily for short periods, nurses could review safety and quality issues that arose the day before or that they could anticipate arising in the day to come.18 Think of the suffering the team was able to avert! In inpatient settings as well as provider practices, teams that begin the day without checking in might find that they experience delays, bottlenecks, and challenges throughout the day that bleed over into patient delays, dissatisfaction, and rescheduling. By starting off the day with a huddle, everyone can understand what issues to expect. They can strategize on how to address them, and they can agree on a plan before patients arrive.

What makes for effective huddling? I’ve found that following a number of commonsense tactics makes huddles more effective. Hold huddles at the same time every day or shift. Start huddles promptly. Stick to a clear agenda. Require that team members participate. Keep huddles short, no more than 15 minutes. Begin and end huddles in a positive way. Focus on solutions, not just the exposure of problems. I once followed a nurse manager at Henry Ford Health System who ran one of the system’s “star” units. It was immediately apparent why this unit was so successful. Maria was engaged and enthusiastic. She couldn’t wait to show me her unit, introduce me to the team, and talk to me about what team members were doing. She invited me to one of her huddles. It was short, to the point, and engaging. She talked about the team’s progress on its quality metrics and asked staff members to address challenges they were experiencing. Instead of bringing up problems, as so many people do in team settings, staff members brought up solutions. The team left feeling empowered and eager to take on the day’s work.

Implementing Interdisciplinary Rounding

In Chapter 5, we discussed how purposeful hourly rounds and leader rounds benefitted both patients and caregivers. Interdisciplinary or interprofessional rounds are a bit different and, as you might expect, trickier to execute. Such rounds take the team approach to the bedside, incorporating the patient as part of the team. In an interprofessional round, representatives from each discipline caring for the patient huddle together at bedside, sharing information about the plan of care, the patient’s progress, and next steps. Although brief, these rounds should allow time for the patient to ask and answer questions about his or her care.

Organizations that have implemented interprofessional rounds have seen better patient experience scores, lower lengths of stay, better employee engagement, reduced mortality, and fewer adverse events.19 Nevertheless, some providers fear such huddling for the same reason they fear connecting one-on-one with patients: they envision being trapped in a room by patients or family members barraging them with “too many questions.” There’s no doubt that interprofessional rounds are not easy. They require a great deal of coordination, teamwork, and leadership. Still, caregivers can minimize the chances by keeping the rounds well organized.

The team should come together prior to initiating rounding and agree on a template to follow. The mere act of doing so serves as a good team-building exercise, and the existence of a template can help keep conversations on track. The team should also define a leader for these rounds, someone (not necessarily a physician) who can keep the conversation moving and end it at the appropriate time. Choose a team member who knows the patient well, who has demonstrated good facilitation skills, and who can assure that the team (including the patient and family) stays focused and initiates therapies discussed during the huddle. Finally, team members should practice interdisciplinary rounding. Just as we must teach caregivers how to connect with a patient, we must also teach caregivers how to perform rounds, exploring who is involved, how each member should participate, and how to end rounds efficiently and respectfully.20

Improving Bedside Shift Reports

After nursing school, I worked in a neuro unit, spending alternating weeks in the ICU and the step-down unit. During my shifts in the latter, we recorded our patient reports on cassette tape (yes, it was a long time ago). Team members in the incoming shift listened to the report and asked any questions they might have before we left for the day. The process wasn’t ideal. Because we didn’t engage in a dialogue and because we didn’t include patients and their families, we frequently experienced communication gaps that compromised the care we delivered.

Our care would have improved dramatically had we conducted bedside shift reports. These reports bring information right to the patient at bedside. Not in the hallway outside the patient’s room. Not in the room but on the other side of the curtain. In the patient’s room at bedside, preferably using the whiteboard in the room and involving the patient in the discussion. Bedside shift reports are an important way of helping patients feel like they are part of the care team. They build trust, accountability, and a sense of camaraderie. The ability to participate and to learn about their care gives patients at least some sense of control, which reduces suffering.

To build trust with patients, introduce yourself and your colleague when commencing these reports. Walk together into the room and greet Mrs. Riley, letting her know that you trust this colleague of yours who is coming on shift and who will be caring for her. Say something like, “Mrs. Riley, this is Gail. She’s going to be your nurse tonight. I’ve worked with her for about five years now, and she’s my go-to person when I have a question. She’s a fantastic nurse.” This helps Mrs. Riley to feel safe in Gail’s care. If you think Gail is a good nurse, and if Mrs. Riley thinks you’re a good nurse because you’ve met her needs and reduced her suffering, then Mrs. Riley will likely think Gail is a good nurse, too.

Here the 56-second conversations described in Chapter 5 come into play. Because you’ve connected with Mrs. Riley during your shift, and you’ve learned something about her that has nothing to do with the reason she is in the hospital, you can reference that information when introducing the oncoming nurse. This provides the oncoming nurse with a conversation starter to build her own connection with Mrs. Riley. Then you and the oncoming nurse can talk together about Mrs. Riley’s progress toward her goals, her upcoming procedures or lab work, her discharge needs, and so on, all along making sure to involve Mrs. Riley in the conversation.

Some caregivers worry that by conducting bedside shift reports in semiprivate rooms, they’ll compromise patient privacy. They claim that in these situations, bedside shift reports simply aren’t feasible. On the contrary, caregivers should still perform bedside shift reports, albeit with a twist. Instead of conducting the report at the foot of the bed, caregivers should join patients at the head of the bed and speak quietly with the curtain pulled between the beds. This way, caregivers can maintain patient privacy and still invite patients to participate in the conversation.

Minding the Whiteboard

In conducting bedside reports, caregivers should make ample use of the whiteboards that are virtually omnipresent in patient rooms. Whiteboards in healthcare settings come in various sizes and shapes and contain varying levels of information. But no matter what form they take, caregivers must recognize that the information belongs to the patient. If it belonged only to the care team, we would have no need to locate whiteboards in patient rooms. In keeping with this philosophy, caregivers conducting these reports should keep the whiteboard where the patient can see it and populate it with information that the patient needs to know, including caregivers’ names and roles, some information about the plan of care and goals for the day, instructions about diet or exercise, and, ideally, the anticipated date and time of discharge. Patients will wish to know this basic information, and they’ll ask about it repeatedly if caregivers don’t provide it. Merely possessing this information provides autonomy for a vulnerable person who otherwise feels out of control. By providing the information and keeping it updated, you help patients feel safe, and thereby you reduce suffering.

It’s not enough to provide this information as part of bedside shift reports. You also have to confer with patients about it. I have often asked patients what the numbers on the whiteboard in their room mean. “Oh, I don’t know,” they say. “It’s something for the nurse.” When I ask the nurse, she says, “Oh, that’s the phone number for the family to call when they’re ready to talk with the doctor!” We need to discuss the information on the whiteboard with patients. How will the family members know the plan of care and actively participate in it if they don’t understand how to contact the physician? Simply writing it on the whiteboard isn’t enough. Have the conversation and make it very clear to the patient and family. It’s a seemingly small detail, but it improves the patient experience and reduces suffering.

Often staff members don’t update the whiteboards, or they leave the information recorded there incomplete. Patients in treatment rooms, exam rooms, or inpatient rooms don’t have much to look at besides a TV, a window, the ceiling, or the whiteboard. So they look at that whiteboard all day long. When the information is wrong or incomplete, patients have a hard time scoring caregivers “always” on anything. If the team members couldn’t keep the whiteboard updated, what else did they miss? An incomplete whiteboard gives patients the impression that you weren’t always there to care for them. In their minds, gaps in information suggest that there must have been gaps in care as well.

Getting Discharges Right

When I worked as a staff nurse, I often found it maddening to receive a physician order that read, “Discharge to nursing home today.” That order came with no notice that the patient was going to a nursing home. The patient didn’t know about it, the family had not chosen a nursing home, no arrangements had been made, and now everyone had to scramble. Sound familiar? Many healthcare organizations take a bit more care than this in discharging patients, but they still don’t do enough to prevent emotional and physical pain.

It’s so important to discharge our patients carefully and thoughtfully, with thorough and repeated provision of information. If patients don’t understand how to take care of themselves, or if their families don’t know how to care for them, patients and families both feel anxious. Even worse, they stand a greater chance of making mistakes in providing follow-up care, with potentially disastrous results, including the need for rehospitalization. In a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (2016),21 researchers found that in over a quarter of readmitted patients, the readmission was considered potentially preventable. In over half of these patients, the readmission might have been prevented if caregivers had taken the right steps during the first admission. Researchers discovered that many of these readmissions owed to factors like failing to schedule follow-up appointments, a lack of awareness on the patient’s part about whom to contact after discharge, or excessively early discharge of patients.

Effective discharge preparation might mitigate many of these common causes of readmission. In some cases, for instance, patients don’t understand how to take their medication, and they ask questions only after experiencing an adverse reaction. Mistakes such as these are potentially quite serious. In a study involving patient cohorts from Brigham and Women’s and Vanderbilt Hospitals, researchers revealed that nearly a quarter of heart disease patients endured “medication errors” within a month after their discharge from the hospital, despite receiving instructions and follow-up. Of these errors, 23 percent were serious medication errors, and 2 percent were life-threatening. The problems identified by researchers included unclear written instructions, poor communication between primary caregivers and hospitals, and physicians’ failure to check on their patients’ recovery often enough. The researchers recommended including the patient and family in discussions about their medications and encouraging patients to play active roles in their care.22

We caregivers have no excuse for failing to discharge patients properly. We know that they will eventually leave the hospital, finish treatments, or move to other levels of care. Our job is to set them up for success when they do. That means we must provide information throughout their care that will help them to succeed. We can’t do that 20 minutes before the patients go home from the hospital, 5 minutes before they leave the emergency department, or 30 seconds before they leave the doctor’s office. Providing information throughout their encounter and in multiple ways helps to assure their success.

To understand how an effective discharge might work, consider a fictional scenario. Let’s suppose that Mr. Jones has been admitted for a right total knee replacement. When he saw his surgeon the week before, he learned that he would likely spend about three days in the hospital. His surgeon told him that he would need a ride to come for him around midday on his day of discharge, but that the nurses on the unit would keep him posted on progress leading up to that. The surgeon also told Mr. Jones about the medications he would probably be taking and the physical therapy he would need. He gave Mr. Jones numbers for physical therapists, along with information about the procedure’s risks, benefits, and alternatives, handing Mr. Jones an information packet and going over it with him. Mr. Jones then went to an appointment for preadmission testing, where he also received information about his procedure and what he would need both in the hospital and after his discharge.

When Mr. Jones arrives at the hospital on the morning of his surgery, his preop nurse verifies all this information with Mr. Jones and his family. Then she asks that they repeat back the information about physical therapy, medications, and discharge plan along with asking if they have any questions about the process. The anesthesiologist then sees Mr. Jones, reinforcing the importance of follow-up physical therapy and taking medications exactly as prescribed. She also confirms that Mr. Jones will need someone to give him a ride home after discharge. When Mr. Jones arrives in his room after the surgery and PACU stay, his nurse assesses him, speaks with his family, and writes on his whiteboard:

Mr. Jones is a retired professor of math at the university.

He is a grandfather of three and has two dogs named Macie and Moose.

Provider: Dr. Jon Allen

Nurse: Sally

Patient Care Assistant: Matthew

Diet: Clear liquids

Exercise goal: Up in chair tonight

Anticipated date and time of discharge: Thursday, 11 a.m.

The next morning, someone in the physical therapy department helps Mr. Jones to ambulate and tells him how the physical therapists would work with him after discharge. His nurse enters and talks to him about issues he might have with walking, asking about throw rugs and stairs at his house. She further inquires about who might take Mr. Jones to physical therapy and talks to him about the medications he would take at home. She asks him to repeat the medication instructions back to her to make sure that he will be safe when he is discharged. She also talks with his family members about what they can expect and what side effects, infection, and complications to look out for. That evening, the next nurse on duty talks to him about the same items and gives him a packet that lists all the information they had discussed. On the final day of Mr. Jones’s hospitalization, the provider comes in and tells him that he can go home. Mr. Jones had already arranged for his daughter to pick him up at 11, and she is there waiting for him. Together, they review the same instructions he has been given by the surgeon in the office, the preop nurse, the anesthesiologist, all of the nurses who cared for him on the orthopedic unit, and the physical therapists.

In this scenario, Mr. Jones is much more likely to succeed after discharge than if he had been discharged with a minimum of notice or information. His caregivers have repeated their instructions not because they’re disorganized. It’s the opposite: they’re working well together as a team, coordinating their messages because they know patients and their families often require repetition in order to process information about their follow-up care. Mr. Jones and his family feel empowered because they are empowered. They know what to do to assist his recovery and to minimize his suffering.

Putting It All Together

As we’ve seen in this chapter, we cannot prevent suffering under the Compassionate Connected Care model without addressing care on the level of the team. By improving the way project teams function, we can improve operations across our organizations, reducing wait times, waste, miscommunication, serious safety events, and many other sources of patient and caregiver suffering. By improving the way patient-facing teams function, we can directly enhance the ability of caregivers and patients to connect with one another. Patients feel safer and better cared for, while staff engagement soars. Healthcare becomes more of what it is supposed to be: a healing and enriching experience for all involved.

At the extreme, healthcare organizations should endeavor to provide seamless, team-based care for patients suffering from specific conditions. Some organizations are already doing this. MD Anderson’s Head and Neck Cancer Program has been lauded as a model not only for cancer care but also for team-based care. In the early 1990s, Dr. David Hohn recognized that “seventy percent of cancer patients required treatment by more than one specialty” and that seeking such care was difficult. Processes typically were organized around clinical specialties (surgical, medical, or radiation technology) that required patients to navigate an unwieldy and bewildering system. To remedy this situation, MD Anderson created its Head and Neck Cancer Center, a collaboration among multiple specialties serving cancer patients. The center locates most specialties in one building. Patients have initial contact through the Patient Access Services Staff, and within 24 hours a surgeon decides whether the patient would benefit from services at the center. If the answer is yes, then the center obtains all the relevant patient data and diagnostics. Patients receive a diagnostic plan and undergo testing before even meeting with clinicians for the first time. After just a day or two on-site, most patients have received a diagnosis and a treatment plan and have completed all their specialty consultations.23 By deploying teamwork to meet patient needs for speed and safety, MD Anderson’s team-based approach has reduced the avoidable suffering and mitigated the inherent suffering that cancer patients experience.

Virginia Mason Medical in Seattle has built a similar system for patients with lower back pain. Traditionally, patients who suffer from such pain have usually seen multiple physicians and therapists and tried multiple medication solutions, to no effect. But at Virginia Mason, patients call one number and are typically seen the same day by a team consisting of a physical therapist and a board-certified physiatrist. For most patients without a malignancy or infection, treatment such as physical therapy also begins on the same day. According to one account, Virginia Mason “eliminated the chaos by creating a new system in which caregivers work together in an integrated way… . Compared with regional averages, patients at Virginia Mason’s Spine Clinic miss fewer days of work (4.3 vs. 9 per episode) and need fewer physical therapy visits (4.4 vs. 8.8).”24 Since Virginia Mason founded the clinic in 2005, MRI scans decreased by almost a quarter. Despite having the same infrastructure and staffing, the new clinic sees approximately 2,300 new patients annually—that’s nearly 900 more patients than it administered under the old framework.25

As both these examples teach us, reducing suffering requires not simply that we colocate caregivers but that we organize care around the patient, providing the full continuum of services around the patient’s needs. In our interdisciplinary teams, we must acknowledge and capitalize on each team member’s experience and expertise. Only by working together in comprehensive and efficient ways can we achieve breakthrough results, reducing suffering far below traditional levels.

In all healthcare organizations, even those with more traditional care models, we must never stop pursuing excellence in teamwork. At one point during a Perioperative Services Guidance Council meeting at Wickerland, we shared positive data trends relating to block utilization, on-time starts, and cost controls. The chair of the anesthesia department nodded at me, saying “We’re doing so well. Can’t we take a break from performance improvement initiatives for a little while?”

“No,” I responded. “We can never stop because other organizations are not stopping. More important, the journey will never be over.”

I continue to believe that. We will always find ways to improve the experience of patients and caregivers, and that makes working well together all the more important. By creating a vision that reflected our goals of world-class, efficient, and effective surgical care by world-class providers and staff, the new administration at Wickerland was able to optimize the strengths of all the stakeholders on the council. That, in turn, positioned us to make ever greater gains going forward—gains that improved the experience of patients and caregivers alike.

Our challenge, and the challenge of all high-functioning teams, was to sustain and deepen this healthy and vibrant collaboration over time. In all organizations, the Compassionate Connected Care model cannot succeed unless the organization itself proffers strong support for both caregivers and teams. It is to this topic we now turn.