"A picture is worth a thousand words."

I hate the way he looks through me like I don't exist. He always shakes my hand like a wet fish! And every time he comes near me, that cologne! Yuck!"

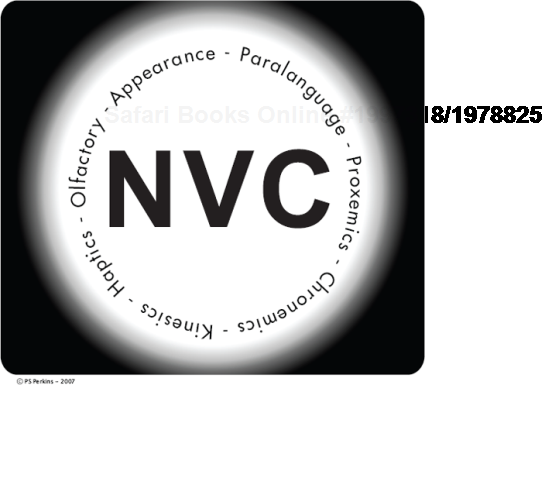

You probably remember reading these thoughts from Jill in the introduction as she thinks about her colleague Richard. How many of the above references have to do with nonverbal perceptions? Nonverbal Communication, or NVC, is defined as the messages we send and receive from others without words, both on a conscious and subconscious level. In understanding that communication can be unintentional as well as intentional, and that unintentional communication is often derived from NVC, we see the large role Nonverbal Communication plays in the dynamics of how people relate to one another in the workplace. This second step in communication awareness is a large part of the lake we discussed in the last chapter.

Warning

The thoughts you express as words and emotions become your habits, which feed your nonverbal language-the manner in which you nonverbally express yourself.

We learn the nonverbal codes of a society much in the same way we learn language, as an integral part of our symbol system. Just as with language, we do not always acquire the most effective nonverbal habits. The messages come from the inside out and are reinforced by others around us, generally using the same set of agreed-upon symbol systems put in place by the dominant members of the culture. We take this same set of communication skills, rules, and expectations into the organizational setting.

Every culture or society has a set of nonverbal messages that are taught and learned by its members to organize a multitude of embedded symbols for the purpose of creating society and maintaining order. All cultures have separately developed nonverbal messages based on their collective realities. These symbols create the reality of the dominant culture, a reality further enhanced by symbols created by the cocultures within the society, who through their language patterns and experiences create alternative realities.

More than your verbal message-the actual words you speak-there are thousands of nonverbal messages you send and receive every day. What type of messages do you send, consciously and unconsciously, in the way you dress, your facial expression, your greeting rituals, your displays of emotion, your gestures, your tone of voice, or your use of space? When speaking of Nonverbal Communication, many automatically think "body language," but NVC is much more than the messages we relay through our physical bodies. A variety of studies, such as the one done at the University of California-Los Angeles by Professor Albert Mehrabian in his classic NVC work, have concluded:

7 percent of meaning is in the words that are spoken.

38 percent of meaning is paralinguistic (the way that the words are said).

55 percent of meaning is in the visual message, such as facial expression.

These statistics reveal that the nonverbal messages we send, and not the words we speak, account for as much as 93 percent of the messages others receive from us when judging our level of trust and believability. Nonverbal messages can be broken down into visual, vocal, physical, and spatial messages. There are several arenas of NVC we operate within all day. Indeed, such communication is a vast field of study that is a primary consideration in many areas of human exploration, including the workplace, architecture, interior design, medicine, education, physical science, behavioral science, organizational behavior, and landscaping. We are vastly more than the words we speak, which are often a cover for how we really feel and experience life. How many times do you say one thing and mean another, or experience others manipulating NVC for a desired gain? An example would be dressing professionally for an interview. We talk to one another loudly in the gestures we use, the space we maintain, and the eyes that reveal all!

We use Nonverbal Communication, consciously and subconsciously, to fulfill seven (7) varied functions: (1) to substitute words, (2) to control the impression others have of us, (3) to complement the words we speak, (4) to contradict our words, (5) to confirm the messages of others, (6) to distinguish relationships between ourselves and others, and (7) to maintain a congruent understanding of the messages within a shared environment (such as the workplace). These seven factors are how we generally interact with colleagues at work.

Think for a minute about the nonverbal patterns found in the United States and the agreed-upon gestures for "stop," "OK," "hello," "goodbye," smiling, and frowning. How about our recognition of space as a way to denote power? Or what about the nonverbal rituals of what is appropriate and inappropriate touching, and how much of an impact touching rituals play in the discussion of appropriate versus inappropriate touching at work? How about the use of color in its ritualistic uses of business versus social or weddings versus funerals? Examples can be seen in the white of a doctor's office or black worn at a funeral. All of these issues are determined by our agreed-upon symbol system of NVC. Notice that as we move into our various communication experiences, we conform to the specific verbal and nonverbal patterns of the environment. We go to work and adopt the jargon, symbols, and appropriate NVC of the organizational culture. These symbols are embedded within the social realities of all distinct cultures, usually greatly influenced by the historical and religious underpinnings of the culture.

NVC is a major factor in all cultures but within its own culture-specific context of appearance, paralanguage, kinesics, chronemics, proxemics, haptics, and olfactory. As we discuss these variables, remember that Nonverbal Communication is culturally bound: its symbols change from culture to culture. We will examine these NVC arenas as they appear in the U.S. workplace culture (see Figure 2.1).

Appearance is the first of our nonverbal codes to examine. It is the outer image you present to the world according to prescribed societal and workplace constructs. All cultures have what we call a standard of physical beauty and acceptance that most members of the culture aspire to. Studies have been done that identify the common denominator of beauty for most humans as symmetry of the body, specifically the symmetry of facial features. Obviously, appearance is an important factor in the communication exchange of humans. Do individuals notice a person's sex, skin color, or apparel as the person makes a first impression? It of course depends on the person and how they were socialized to process these attributes. We have all heard the adage "don't judge a book by its cover." But let's face it; that is exactly what we do each day when we meet and engage people in the workplace. Only a very small percentage of the people we meet on a daily basis become players in our movie, due to what attracts us to one another or the circumstances that compel us together, such as work.

What areas of physical appearance do you tend to pay a lot of attention to? Some look for a nice smile. Others say the eyes are the windows to the soul. Some love to see a man in an expensive suit with nice shoes. Some love gray hair around the temples. Tall, short, plump, thin ... the lists of likes and dislikes are endless, but the point is that we are an image obsessed culture. Your image, your visual impression, is very important, especially in a youth- and beauty-conscious culture such as the United States. This is also the major communication arena within which social comparisons often operate.

Appearance in the workplace is often used as an indicator of appropriateness, professionalism, and position within the organizational setting. Growing up, I remember my father being one of those "blue suit" guys with IBM. It was a part of the culture. Many institutions have prescribed dress codes, but there are many that don't, and the variable of diversity adds a lot to the cultural appearance factor. We live in times where Middle Eastern and Arab dress is often met with stereotyping, prejudice, and fear. We live in times where Western dress is sometimes viewed by other cultures as too revealing. The workplace brings these dress mores together. How do you perceive yourself in this area of communication? Are you acutely aware of the nonverbal messages you send and receive all day through something as personal as your physical appearance?

I often work with individuals from urban communities who have adopted patterns of dress that identify their unique brand of seeing and experiencing the world. This sometimes includes apparel such as very low-riding pants, untied sneakers, hair wraps, flip-flops, baggy shorts, and tattoos. Many would say that this would not be considered the appropriate attire for professional setting. To these youth, it is a way of expression that identifies their unique experiences. Many of you reading this book have already conformed to the prescriptions put forth by the dominant culture of what is acceptable patterns of appearance, as well as what is considered culturally beautiful. There are many who are willing to take whatever measures necessary to be considered desirable.

One of my favorite episodes from The Twilight Zone, the program hosted by Rod Serling, was about a young woman who was going through her eleventh medical procedure to alter her facial appearance to meet societal standards. In this particular conformist culture, it was a crime to look different. (Rod Serling was a master of social commentary, using Twilight Zone episodes as a cover to tackle some of the complex and sensitive social issues of his time.) When the bandages were removed, the operation was unsuccessful and the patient was to be transferred to a colony to live with people of "her own kind." The genius of the episode lay in the fact that the viewer was never given a straight-on look at the faces of the hospital staff, only shadows and glimpses of body parts. When the results of the surgery were in and the "lights were turned on," we see that the normal people have faces that are contorted and deformed, all alike for the sake of conformity. The patient was transferred to a colony with "people of her own kind." The episode is entitled "Eye of the Beholder." Its messages are as clear and relevant today as they were in 1960.

Many remain in a constant state of dissatisfaction because they never seem to measure up to the ideal. Approval issues, such as image in the workplace, also hurt the organization's bottom line in the amount of money and human capital lost because of time devoted to cosmetic surgery, cosmetic dentistry, spas, nail and hair salons, and so on. Maybe we need to look at this very factor affecting business productivity and how we can create more inclusive environments.

This can be particularly difficult in the competitive arena of work. In our patriarchal culture, white males dominate the corporate decision-making body. As a result, their paradigms of appropriate versus inappropriate dress are the standardized dress codes of the workplace. There are many experiences that have been documented about various organizations adopting dress code mandates specifically aimed at a particular cultural pattern proscriptions such as no facial hair, no braids, no locks, no long nails, no head wraps, and so on. These dress codes are made to make "some" individuals more comfortable and accepted than others. A better paradigm of inclusion would be to foster organizational environments that encourage apparel distinction that is culturally expressive yet professional. If the "look" is in no way a hindrance to work productivity, what's the problem?

How can we see and appreciate uniqueness, yet at the same time be able to effectively compete in a work culture that too often offers very narrow prescriptions of professional image? Part of my self-healing process has been the need to redefine and reprogram the concept of beauty I was programmed to believe in. You must do the same. If you presently fit the ideal, still realize it is not all that you are. Beauty does fade, especially if it is totally based on outward appearances. For those of us constantly finding ourselves having to compete in the appearance game, often accumulating more and more stuff to satiate the desire to fit in, it's high time to create a new paradigm.

No longer judge yourself by the narrow, shallow definition of beauty and its accoutrements. Broaden your definition. Just like you try new foods and acquire new tastes, do the same with your prescriptions of beauty. Do not allow Gucci, Pucci, Larucci, or Fubu to be a measurement by which you define your self-worth. But always remember, communication-whether it is verbal or nonverbal, such as with appearance-is appropriate or inappropriate, never good or bad. This is a very important point. Communication is always based on the realities of the sender and the receiver. The closer the shared realities, the more likely the shared symbols will be congruent and thus more compatible.

So, getting back to the young urban hip-hop dresser, enjoy your uniqueness but understand that all communication is governed by setting, time, and place. Take an inventory of how you present your professional best in terms of the work environment. Appearance sets the stage! Are you satisfied to just mirror everyone else or do you adopt an attitude of personal excellence? Based on the setting, you may need to adopt a more conservative dress style for the workplace. Maybe you need to be more relaxed or season stylish. Extend your considerations about your wardrobe beyond clothes to nails, hair, colors, shoe types, and other complements that can greatly affect the visual image. And, of course, it never hurts to get a second opinion from someone we trust or from an expert when trying to find the right look. Rule of thumb: When in Rome, do as the Romans; when at home, do as the homeys! Make your communication appropriate for the setting to win the prize you are seeking-a promising career path.

Our next NVC code is paralanguage. Paralanguage is not what you say, but how you say what you say. It is the vocal qualities that surround your words. It is tone, pitch, emphasis, stress, inflection, volume, pacing, accent, dialect, pausing, silence, and a host of other vocal variables unique only to you. However, every culture has prescriptions for what sounds pleasing, professional, educated, or illiterate. These often act as a way of categorizing people and even stereotyping some. This can be especially detrimental in the workplace.

I have worked with dozens of individuals trying to "fix" their speaking voices to come more in line with prescribed patterns of acceptance. This is basically the General American accent we hear on national broadcast networks. I have worked with individuals seeking accent reduction, dialect reduction, volume increase/decrease, projection, help with stuttering, lisp, nasality, and so on. There have been times when an employee will share that a promotion has been stalled time and time again because of the lack of authority in the employee's voice, or because of a cultural accent that the employer feels will be a detriment to supervisory authority. There are people who insist they have been labeled "slow," "uneducated," "ghetto," and other derogatory terms for no other reason than the way they sound. How often do you label someone as educated or uneducated, professional or unprofessional, because of the way they sound?

The interesting factor behind paralanguage is that it is something that can be adjusted if desired. There are many who decide to take instruction in accent reduction or voice and diction in order to bring their patterns of speaking more in line with the dominant culture. Some feel this is necessary in the pervasive climate of competition. However, I advise individuals to be careful concerning their choices to lose their native tongues or purposefully become less ethnically identifiable. Language is where we find our identity. When we lose our language by choice or force, we lose a very important means of connecting to who we are. This is an interesting phenomenon in the United States. Europeans who settled the colonies of North America came from a myriad of European nations: I mean the Swiss, Germans, Irish, Dutch, Norwegians, French, and so on. Many, during their arrival at Ellis Island, changed their names and immediately began the process of losing their languages and accents of birth. Many purposefully did not hand down their ancestral languages to their children or their children's children, many for fear of ostracism. As a result, we have a major portion of Euro-Americans who have no connection to their historical languages. Some do not see themselves as ethnic; everyone else is ethnic. Yet there are hundreds of ethnic Euro dialects maintained by older generations and revitalized by a young generation throughout the Americas trying to hold on to its heritage.

Take another co-culture in the United States. The majority of African-Americans are the descendants of African slaves. During the centuries of slavery, Blacks were forbidden to speak their native tongues. In addition, they were not allowed to read or write English. Not only were they disconnected from their heritage/identity, they had to adopt a language that was not designed to express their personal experience in a favorable light. Blacks created pidgin dialects to survive and to try to re-create the cultural connections they had lost. Today most African-Americans still do not speak an African language or know where they are descended from. They have, however, always contributed abundantly to the evolving English lexicon and American patterns of speaking. Many African-Americans speak what has been termed Ebonics, Ebony Phonics. There is still controversy as to whether this is a language or a dialect. I tend to refer to it as a dialect, much like Yiddish, Patois, or Spanglish. I use Ebonics comfortably and proudly within the settings where I feel it is appropriate to do so. These are primarily my home and social settings. I have also mastered General American English for the purposes of professional survival. I understand those who do and those who do not wish to operate bidialectically: again, communication is appropriate or inappropriate, not good or bad. I have several colleagues who have experienced what they consider workplace discrimination due to their unique cultural vocal patterns, whether it's speaking too loud, too soft, too slow, with a heavy accent, or in patterns riddled with cultural markers.

Our regional accents, dialects, and unique vocal patterns are what add the spice of diversity as we encounter each other within the myriad of communication settings where we find ourselves. The above examples focus on a prevalent concern in a work environment where conformity is ultimately rewarded over true individualism and without regard to the equality we espouse in our beliefs. It becomes too easy for some to forget that their origins are not of this land, a forgetfulness that can lead to feelings of ownership and ethnocentrism. For others, who have endured the identity crises of the absence of cultural and historical language, feelings of isolation and devaluation have become generational. Language equals social reality.

Determine for yourself whether your patterns of speaking are advancing your professional goals. Realize that symbols, verbal and nonverbal, create the organizational reality you are operating within. Your vocalics, or paralanguage, is a part of the message system others respond to every time you speak. You can change your pitch, tone of voice, rate, pacing, or any number of paralanguage qualities. However, your paralanguage is the unique personal identifier that distinguishes your voice from others. How often at work do we describe someone by saying, "You know the one that sounds like _____." We use paralanguage (vocalics) as a key identifier when describing others and when judging them. We categorize, label, and stratify others based on the way they speak. But we must wisely consider that accents, dialects, silence, cultural utterances, pitch ... all these are the adornments of the verbal message. Paralanguage is to words as mind is to brain. It is the essence of our words.

Our next nonverbal code, kinesics, is the movement of the body in relation to sending and receiving messages. It includes gestures, stance, posture, walk, eye contact, facial expression, and all other body movement engaged in relaying messages. When talking with colleagues, do you talk excessively with your hands? Avert your eyes when speaking to the boss or being spoken to? Walk down the hall with an easy saunter or a lively step? Do you stand erect or tend to lean on one hip? All of these body motions convey a message to others about you. Remember our definition: communication is experienced whenever meaning is attributed to current behavior or past behavior.

People differ in their use of body language; some tend to be more physically animated than others. This is often a cultural and/or family trait. It is important to understand that during our enculturation process as children, we learn thousands of nonverbal symbols that convey a variety of messages through the body. This is how we distinguish a frown from a smile, a wave hello from a wave goodbye, a look of approval from a look of dismay. I grew up with a mother who only had to give you that look, the one that immediately put you in your place. Eye contact as a variable of kinesics is one of the most powerful tools used to convey messages within every culture. With it we convey power, confidence, fear, love, and the list goes on. In the United States, eye contact is a primary determinant of the impression an individual gives of believability and trust. I have observed many lessen their chances for success during the process of interviewing because their eye contact did not convey a message of confidence, honesty, and self assurance.

There are cultures where subordinates are not allowed to look directly in the eye those with sanctioned authority or of superior position. However, ours is not such a culture, and it is imperative that, in this highly competitive society, we understand the power of conveying assertiveness through our nonverbal communication. Check out your posture, your stance, and the face you wear when you think no one is looking. How engaged is your facial expression when you're in a meeting or speaking one-on-one with colleagues? A "real" face-lift is one that conveys a message of openness, self-assurance, and assertive listening.

Warning

We listen mainly with our eyes.

Too many of us walk around looking as if we carry the weight of the world on our shoulders. As a result, we often repel the very opportunities that may open new doors and horizons, opportunities that are only capable of appearing when you are present and focused. What message does your body language convey? Are you open to receive all that can be yours? If you are not sure, ask someone at work you trust. Awareness is the first step toward empowering your kinesics communication (see Application 2.1).

Application 2.1 - Seeing Is Believing!

Observe yourself. Engage in self-monitoring. Do you look at people when they are speaking to you? Do you look away when speaking to others?

Watch your patterns of eye contact with supervisors, coworkers, customers, and/or employees.

Record three occurrences of your eye contact behavior in a workday, preferably with different groups. Recognize how you perceive your position with different individuals based on eye contact.

Our next NVC code, chronemics, is the study of time as a nonverbal system. Time, as we understand and have adapted to it, is a relative concept. The way it is segmented, treated, and observed is a societal construct determined by culture. Time orientation in cultures may be past, present, or future. Some cultures concern themselves with aspects of their past history to determine their present, and other cultures may operate mainly in the present or else concern themselves with the affairs of the future. Cultures' level of technological advancement versus a more agrarian level will affect how they observe time. As a highly technological, future-oriented culture, the United States is very time conscious. It is what we call monochronic. Time is segmented according to activity; "time is money." In polychronic societies, time is a more holistic construct determined by ties to your family, clan, community, and nature. If you are to be successful in a culture that values time according to activity, you must construct your life around the responsibility of being on time for the prescribed activities or else risk being labeled irresponsible and unproductive. We look at the code again in Chapter 7, but I want to share a cultural perspective about chronemics.

Several readers may remember the cultural phrase "C-P time" or "colored people's time." An individual would say, "Pick me up at eight, and I don't mean C-P time." We understood that to mean "late," probably thirty minutes or more. But the actual marker of Blacks being prone to lateness or disregarding time came as a result of polychronic people being forced into monochronic patterns of dealing with time. West Africans were introduced into European-American time patterns foreign to the Africans' construct of time and its use. Others would try to use the disjunction as an indicator of the "inherent" laziness of Blacks, as witnessed by caricatures of the early to mid-1900s that reinforced the stereotypes of slothfulness. As I studied the construct of time within a cultural context, I began to realize the import of this cultural assignment toward Africans and other collective cultures. It was about the perception of time and its relationship to the context of the group. For the Africans, time was something to be used, not be used by. The social constructs of time collided (as they sometimes still do) and different time constructs came into contact with one another; hence the construct of "C-P time." Another example might be a vacation in the Caribbean, where the popular phrase "No problem, man" gives a glimpse of that culture's time consciousness. Or a siesta in Spain in the middle of the afternoon. A better definition of C-P time would be "communal potential time."

In U.S. culture we use time to indicate an individual's level of importance. The doctor may keep us waiting, but we do not keep the doctor waiting. We arrive fashionably late when we want to be noticed. We, as a culture, are said to have more stress-related diseases than most cultures because we are always in a hurry and our diet and health reflect this hurriedness. Think about your lunch break and fast food. When we examine time as a factor in the workplace, immediately we are connecting dozens if not hundreds of instances where timing is critical. It's always critical; that's why we have dead lines! Again, this is another arena within the work environment that affects bottom-line costs. Too many individuals are experiencing chronic absenteeism due to stress around time consciousness and constraints. Many studies have revealed that employees perform much better in environments where they are functioning at a productive level but not a destructive level. Time schedules legislated and strictly managed create stress-filled workplaces. The environment itself offers few if any destressors. It's an environment of one deadline after another, and very little collective, informal time. Robert Kegan, author of In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life, writes, "People grow best where they continuously experience an ingenious blend of support and challenge. The balance of support and challenge lends to vital engagement." That needed support usually involves creating a more user-friendly working environment.

Employers need to first take stock of their pool of human capital. Consider the varying perspectives about time that may be exhibited in the office experience. Individuals that experience high family involvement and other communal experiences will likely be very valuable working in teams and with long-term projects. Employers should consider "lunch breakouts" to gather small groups for department discussions under a nonthreatening, nonurgent time frame. Think about what type of scheduling needs to be considered and how far out to make sure the team can move with relative ease through the project (see Application 2.2).

Think about how time is dealt with in your professional and personal life. Whose race are you running, and going where? How do you see yourself in connection to time in the office, around your colleagues? Maybe we need very different constructs for how we handle time in our professional lives and in our social lives. I know I did! I now go to the movies to relax, not to be on time. I now call my friends to chat, not just check in. I maintain my high level of time consciousness at work, but I give myself more time to get the job done.

Warning

It's time to realize that the only person you are competing with is yourself and it's never too late to start your personal race toward self-fulfillment.

Application 2.2 - Is Time on Your Side?

Circle the candid answer and rate yourself.

How often do you rush through lunch? Never Sometimes Always

How often do you find yourself rushing your colleague's conversation, even in your head? Never Sometimes Always

How often are you late to work or to a meeting? Never Sometimes Always

How often do you feel rushed to finish an assignment at work? Never Sometimes Always

How often are you distracted by other things you need to be doing? Never Sometimes Always

Score system: Never = 1 point Sometimes = 3 points Always = 5 points

Results:

1–5: You have mastered your time.

6–15: Continue to lower your blood pressure and cholesterol.

16–25: Promptly admit yourself to the nearest ER.

Proxemics is the study of space and spatial relationships as a nonverbal code. It also includes our use of objects and artifacts. The concept of space, as with the other NVC arenas, is that it is culturally bound. We highly value space in the United States. We treat it as a commodity. It is used to establish privilege and prestige. It is used to establish boundaries of success and power. It is used to protect one group from another. We aspire to big homes, sprawling grounds, huge office space, luxurious SUVs, and the like. We tend to distinguish the importance of an individual based on how much space the person has acquired. When you enter the boss's office, or if you're the boss, notice how much size and comfort play a role in distinguishing the supervisor's space from others'. Our office settings are full of cues that size matters!

Within the organizational context, we determine our relationship with others based on the amount of space we keep between them and ourselves-intimate distances versus more professional or public distances. Too often we assume this is the same everywhere, but it is not. Societies that have a collective consciousness see space as something to be shared. I often have conversations with individuals about how they were invaded at a checkout counter or a bank line by some person who was too close to them. Or the office worker who time and time again complains about a coworker violating their space. Think about the distance that you keep from a close colleague versus a "superior." Think about the way conference rooms are arranged or meeting spaces are prearranged. We lock our office doors to keep others out of our private workspace. This is based solely on the cultural adaptation of how we use, distribute, and operate in space.

U.S. Spatial Distance Mores

Intimate Distance-1 to 12 inches-Those we reach out to and touch

Personal Distance-12 inches to 2 feet-Friends and close associates

Social Distance-2 feet to 4 feet-Colleagues, doctor, mail clerk, ...

Public Distance-4 feet and beyond-The ones labeled as "untouchables"

Materialism is one of the most important values of U.S. culture; we spend a lifetime acquiring the things that in our society represent having "made it." All societies place a certain value on things within their environments, but obviously some more than others. Notice how we treat our office space. How personal is it to you? Do you have an office, a cubicle, a corner, no space? Observe your desk for a moment. Any artifacts? What are they? Look around at your colleague's work spaces. Do you develop an impression of them based on their space? I worked with a fellow teacher for years who shared an office in my quad. The office was filled to the brim with papers, books, student projects, and so on. It was so packed that the instructor never went in there to sit, just to gather what he needed. He never counseled students in his office. Interestingly enough, his outer appearance was also disheveled and a bit slothful. The office situation finally got so bad, he was sent a notice to clean up the place, maintain it, or go without! Remember, how we use our space says something about us. And the boss notices!

How secure or insecure we feel in our space determines how we live in our spaces. Michael Moore, for his Oscaraward-winning documentary Bowling for Columbine, paid a visit to some neighborhoods in Canada to see if what he had heard about Canadians not locking their doors is true. The film shows him opening the doors of several homes that were not locked. Interviewing Canadian citizens, he listens to several attest they did not feel the need to lock their doors. They felt safe. Moore was surprised by their cultural outlook and the striking difference between their culture and U.S. culture, which advocates locking our doors consistently. Fear?

Observing a group of college students during an extended stay in Europe, I was struck by their acute awareness of how space did not have the same meaning and value as it did for them back in the United States. They consistently marveled at the small cars, extremely efficient use of space, close proximity of buildings and homes. Many quickly surmised that maybe they did not need as much space as they thought they did, nor all the objects and artifacts they used to fill their spaces.

What is your assessment of space in your life? How do you establish relationships based on your approach to space within your home and other communication environments, such as work? What are the taboos you are operating with and may not even be aware of? Are you isolating members of your team, possibly because of your strict space constraints or your lack of understanding or respect for U.S. spatial mores? What is the value you place on the things in your life? As the global village continues to shrink and more and more of us experience daily contact with others, it is important that we are aware of humanity's variations in spatial awareness and usage. We must make a global assessment of how our unique concept of space may not be in the best interest of a world where physical and natural resources are steadily being depleted and some being brought to the brink of extinction. As you read this book, what is the latest discussion on global warming and how is it affecting the way you live? Obviously, the concept of space and how we view and use it are very dire issues within the global community and impact every aspect of human existence.

The organizational space is a critical component to the flow and ease by which communication circulates through an environment. Is the meeting space comfortable, hygienic, and aesthetically pleasing? Do its colors stimulate thought and creativity? What type of meet-and-greet spaces does the organization promote for camaraderie and trust stimulation? Organizational space and spatial relationships silently operate to encourage the flow of communication or to stifle the flow. Which effect does your institution promote? (see Application 2.3).

Haptics is the nonverbal code of touching and touching behaviors as experienced during human communication. Cultures engage in a variety of touching rituals that reinforce the established do's and don'ts of public and private touching. Generally, most cultures have some taboos concerning touching that is invasive, violent, or perceived as unnatural. Within the context of U.S. culture, public displays of touching are not as taboo as they used to be, say, during the Puritan age. However, we do have established societal rules for public display, and we try to stay out of the privacy issues of a home unless there are issues of endangerment, such as with abused children.

Application 2.3 - It's About Spaces!

Take an inventory of the organizational space. Are you stimulated when you walk through? Are there informal gathering spaces?

In each space you visit, make a comment about what works and what could work better.

Think outside of the box.

In the workplace, we have the same or modified codes of appropriate touching, though often a bit more stringent due to concerns over harassment and diversity issues. The United States is known throughout the global marketplace for taking an informal perspective on touching in the work environment and relationships. The occasional pat on the back is permissible. Handshakes should be firm with meaning. An occasional peck on the cheek between some coworkers is OK. Some members in the workplace may be considered too aloof and others too "touchy-feely." How do you relate to touch in your intimate, social, or professional communication environments? How do your children, friends, colleagues view your approachability? Do you cringe when others try to give you a friendly embrace? How is your handshake: weak or limp, strong or clammy? (Remember Richard's fish handshake for Jill?)

Overall societal touching mores reveal the United States is pretty much in the middle of the road. We engage in more public touching than the Japanese, but not as much as Italians. We have a variety of greeting rituals that include formal handshaking, hugging, kissing on the cheek, backslapping, elaborate posturing, and so on. These rituals are grounded in our predominantly Judeo-Christian, patriarchal, and heterosexual culture. What is inappropriate for men is often seen as appropriate for women, and vice versa. Such clear demarcations have added to the complexity of gender relationships within the culture.

All of these responses to human touch are a matter of conditioning, but they can make or break our work relationships as we interact with diverse others in a culture full of ever-changing and ever-broadening experiences of human contact. This is why understanding sexual harassment in the workplace continues to be an area of concern due to the ever-broadening relationships men and women share, especially women from cultures outside the dominant U.S. culture.

Organizations should consider the gender and cultural makeup of the workplace environment in an effort to understand what types of touching mores may be present. These attitudes need to be taken into consideration and possibly attended to during orientation sessions that focus on workplace cultural dynamics. Organizational norms concerning appropriate and inappropriate touching should be established, not only as a sexual harassment issue but also a diversity concern.

The last code we will examine in this section is olfactory, or the study of smell as a nonverbal code. Smell is often deemed the most memory-triggering sense of all five senses. We have strong attachments to what we consider good smells, powerful reactions against those we consider bad. This fact affects the way we live, eat, and interact with one another. How many times have your senses been assaulted by something you did not think smelled good? In the United States, we have a strong sense of what we consider to be pleasant smelling. Often, to those outside U.S. culture, we appear to be very sterilized. We shrink-wrap our foods, put our refuse far away from us, and utilize a variety of products to mask personal and societal odors we consider unpleasant.

Take body odor, for instance. Many societies feel more comfortable with natural body odors, enjoy the pungent smells of foods and spices that come through their pores, as well as have a different concept of what is clean, one different than the need to be odorless. I have advised some individuals new to our culture to buy new wardrobes or engage in the practice of using antiperspirants to deal with issues of body odor, not because they were not clean but because they did not "smell" the way we are used to. I have also had to advise travelers to adjust their sense of smell for the unfamiliar and often pungent odors they may not be used to. Again, as our global communities get closer and closer, we will all need to make adjustments in our levels of comfort, adjustments based on more heterogeneous paradigms of nonverbal behavior, including smell.

The workplace is no stranger to this situation, and there have been many instances where colleagues were uncomfortable with a smell belonging to a coworker, whether because of perfume or hygiene. There are times when people turn their noises up at an unfamiliar food with an equally unfamiliar smell. We all need to be a bit more respectful and adventurous in these cross-cultural experiences, or at least considerate.

You can see how the Nonverbal Communication symbols and messages embedded within the fabric of a culture are often the defining attitudes of how we interact with one another. NVC takes us underneath the surface of people's likes and dislikes, preferences and prejudices, the attitudes that so greatly affect their outlook and interaction with others. It is not what we say but how we say it that establishes our work relationships. Empower your communication environments with the knowledge of these basic but powerful nonverbal communication concepts. Create a better understanding between yourself and the people you interact with nonverbally every day. Use your nonverbal communication as a means of supplementing your verbal messages so that they are congruent; avoid being labeled a walking contradiction. Use NVC to empower your interviews, evaluations, department meetings, and public and impromptu speaking opportunities. Your awareness and manipulation of the NVC arenas of step two offer a whole new focus in repairing and enriching the organizational environment.

You have journeyed from step one to step two: understanding the connection between your self-image and your self expression through nonverbal language. As you now move yourself into the mental, emotional, and physical space of others, you take you with you. We watched Jill move through her day with her Intrapersonal and Nonverbal communication into each and every communication event she experienced at work. The Communication Staircase offers insight into the interconnectedness of all your communication experiences, starting with you!

Q&A Nonverbal Communication

Q: | Dear PS, One of my coworkers talks really loud! So loud it gets in the way of focusing on her message. She's a great worker though! |

A: | It's interesting and very true that our nonverbal message will always count more than our verbal message. This paralanguage difference can be a serious communication barrier. Culturally, we have a comfortable and acceptable decibel-level-of-volume etiquette. When anyone operates outside the acceptable levels, too loud or too soft, there is a level of discomfort. Tell her. Be sincere. Ask if she can tell that her volume is usually above normal levels. She may not know or may confide she cannot help it. Work out a signal with her to help her gauge. |

Q: | I have an employee who is habitually late to meetings. He is punctual for work, but meetings are a problem. And he always has a good excuse! |

A: | If he "always has a good excuse," I would ask myself, as the initiator of these meetings, is he the only person lagging? Are other members overstretched? Are you "meeting" your people to death? Is the problem a time cultural barrier that has not been addressed? First, examine the meeting culture of your organization. Depending on your analysis, you may need to approach the late member and stress meeting etiquette or enroll him in a time-management workshop. You can also choose to have "stress free" gatherings that combine lunch, recreation, or coffee chats with agendas that are not too pressuring. |

Q: | I really do not appreciate the way my colleague keeps his desk area. It's really messy and I am embarrassed to bring clients into the area. |

A: | Since your area mate may not be the only one in the department suffering from "messyitis," I would suggest that human resources or the facilities department send out a notice in the newsletter or an interoffice memo requiring a certain standard of workspace image. Stress the client contact with the work area and the importance of image. You can also stick a note on his desk saying CLEAN THIS CRAP UP! Just do not sign my name. |

Q: | Q: I am uncomfortable with how one of my colleagues consistently invades my space! No matter how much I back up, she keeps closing in! I think she is Hispanic, so I do not know if this is a cultural thing. |

A: | You are right that not everyone has the same personal space requirements, and ours in the United States tend to be very guarded. And yes, it may be cultural in terms of the awareness of U.S. personal boundaries. If your company is diverse, especially if it includes first- and second-generation immigrants, your orientation programs should include a communication component that introduces the employee to Nonverbal Communication in the workplace. Please be a good coworker and let her read the material about nonverbal issues and culture in this chapter and Chapter 7. You will improve her chances of success! |

Q: | I have a member of my team who wears clothing I think is a bit informal for the workplace. It's more like something a young woman would wear to a club. I am a male supervisor and I find the topic a bit sensitive to broach. Any ideas? |

A: | Yes! Engage a mature, tactful senior female member of her department and talk with the senior member privately about your concerns. If she concurs, then ask her to facilitate the young lady's awareness. I would suggest the three of you meet. After you have introduced the need for a "work-related observation," you leave the room and let the female member talk with her and advise her of more appropriate choices. You can request that they both contact you afterward for further clarification if necessary. You can also call HR and ask that they approach the worker. But you are right to seek support. Also, don't forget to tell her about the areas she is doing well in. |