"A threefold cord is not easily broken."

I recently engaged in a conversation with a college student who shared her absolute disdain for group projects because there are always "the strong students and the weak students, and the harder-working students have to shoulder the burden of the weaker ones. It's not fair!" This was a reoccurring chorus from many individuals required to take the Small-Group Communication class. I told the student, "Yes, there will be stronger and weaker contributors in a group, but I do not agree that it's not fair to require this type of group work." She looked at me with this look of "what planet did you come from?" I continued, "When you are working for a company that has a variety of departments dependent on one another to create a complete product, you are only as valuable as your contribution to the whole. Can you make the company successful alone?" Interestingly enough, though Small-Group Communication was always the smallest of my classes, it was also one of the most impacting. Individuals shed tears when it was time to part. They had come to understand the value and joy of working with others. Exactly how do we get things done in a society where individuals are hyperindividualistic, highly competitive, and fearful of working with others?

This is not an uncommon discussion when dealing with the subject of teamwork. Out of the Los Angeles riots of 1992 came a now commonly used phrase: "Why can't we all just get along?" Why can't we? Small-Group, or Organizational Communication, can be defined as communication that includes multiple perspectives, all trying to achieve goals that can be seen as both personally and collectively beneficial. This fourth step of effective communication requires that we write into our daily script the personal integrity, confidence, and communication skills necessary to be effective in our group settings. Organizational members often wonder what makes a winning team or organization. The answer is simple but the hardest formula for many organizations to achieve:

Warning

A winning team is composed of members who contribute their individual best collectively!

Remember Jill's group experience? Can you see how Jill's failure to bring her individual best to the afternoon meeting precluded her chances of a successful experience? What if Jill had not woken up on the wrong side of the bed and continued her morning in a disgruntled manner? What if she had been able to wear the outfit she planned and felt good about her appearance? How do you think these communication experiences may have impacted her mood at the afternoon department meeting? The noise in her head prevented her from being open to other perspectives in the group. She engaged in selective listening from the onset. Jill brought this attitude with her to the experience and looked for validation of her dissatisfaction throughout. Replay for yourself how your day progresses into an experience self-created. Do you have an afternoon mood? Replace it with your purposeful thoughts of team productivity and self-satisfaction.

As we strive to individually contribute to the collective best, we must understand why it is difficult for many to do so. What are the patterns and habits that have become the hallmarks of self-preservation? Many of us have been enculturated into the value system of individualism. An individualistic culture sees the individual as the single most important unit of the society. From individualism we create free enterprise, competition, democracy, equality, materialism, and many other expressions of the liberties of the single unit. Individual rights and freedoms are paramount to the ideal of a democratic society. To this end, we set up our organizations to in some way become an economic expression of the values that are important to our worldview. These ideals become the way we do business with others. The other end of the spectrum reveals cultures that are collective in nature and establish the society based on in-groups versus out-groups. The family, clan, or tribe is the most important unit to the society. Individual rights are secondary to the good or survival of the in-group. Members of the in-group work together cooperatively. The out-group is that clan, tribe, or group that does not share the in-group's point of reference or worldview.

There are benefits to both individualism and collectivism, depending on how a society makes use of them. However, these ideologies can also lead to complex social and political concerns. For instance, under the guise of individual freedom the push toward conformity still prevails. Two examples would be the narrowly defined concepts of success and beauty. The "every man for himself" competitive philosophy many adopt in the workplace to get ahead is not one that encourages the team or group ethic. This can be and is often very damaging to the vital unity of the organization. There is also the narrow dominant perspective of beauty, which creates a very sterile culture regarding what is defined as appealing or acceptable. This is very prevalent in the workplace, as witnessed in Chapter 2 under the discussion on appearance. Imagine how many individuals from varying cultures adjust their ethnic look or attire to fit into the "corporate look." So whereas we say we value individualism and prize equality, we do so only within the constraints created by those in charge. There are many individuals who feel they do not personally contribute to the organizational culture. They believe they are required to merely fit in. How can they bring their individual best and blossom to contribute to the collective success? (See Application 4.1.)

Within the cultural framework of collective societies, many are strongly encouraged to conform to the will of the group. And, yes, sometimes in a way that negates individual voices. There can be the danger of groupthink. Collective societies encourage members to subject their individual desires to the collective need. Various forms of autocratic leadership are often prevalent in collective cultures. These cultures are more homogeneous and strongly encourage members to conform for the good of the group, to maintain traditions and ancestral values. It is the in-group that matters. Here we do have the sacrifice of self for the group; however, one must still be a part of THE ingroup. Ethnocentrism exists everywhere. Read Chapter 7 to engage in this discussion further.

Application 4.1 - Individualism and You

How important is individualism to you? Have you ever thought about the impact this concept has on the organization?

What ways do you advance the focus of individualism in your department? Are you a team player? Do you make sure others take note of YOUR efforts even when the project clearly was a team effort?

Taking an inventory of how much you value individualism and allow it to play a role in your group dynamics will definitely help you to see the need to balance this trait against the needs of the group and organization.

When examining our work environments, we foster organizations that encourage individual competition but rely on group efforts and cooperation. Statistics on company failures, employee attrition, and turnover rates provide evidence that there is imbalance in the areas of competition versus cooperation. Is it one or the other? We see there is still the proclivity, no matter which ideology, to not hear the other perspective if it is not rooted in your own worldview. Both sides unchecked can lead to extremism. Is there a middle ground? The combination of cooperation and competition creates a synergistic model of co-opetition, a term coined by Raymond John "Ray" Noorda, the CEO of Novell between 1982 and 1994.

Within the Small-Group Communication setting, I define co-opetition as the need for every person to contribute theirindividual best to the collective. We can recognize co-opetition in the workplace because members of the organizational culture begin to own the experience they are having. They begin to recognize their self-contribution and the equally valuable contributions of others. This translates into communication patterns that are both self-affirming and climate supportive. We will begin to foster institutions that create collective merit systems that recognize the contributions of the whole group on a project. Too often we single out individuals, when behind them stood a number of others who helped to carry the torch. I have often envisioned participating in a game show where the winner would be the team that did the most to help the opposing side, AND both sides would win prizes. The questions or exercises would be challenging and stimulate a lot of excitement, but co-opetition would be the driving force (see Application 4.2). Some may say, "Ahhh, here we go again! Competition is good for you! You need to be assertive!" Maybe, but remember: too much of anything ain't a good thing.

Application 4.2 - Co-opetition Project

Have a contest! Come up with a good work project that you need completed; maybe a quarterly review of the communication flow within the organization.

Get all the departments to work together to prepare the report for management. Give "co-opetition points" to the division that supports the others' efforts.

Allow the project to transpire over a period of time so there is no heightened stress. Reward a bonus for team effectiveness and synergy for the final report and the group that receives the most co-opetition points.

Small-Group Communication requires a broadening of our communication abilities to include three or more perspectives, all operating from different perspectives, which are often assumed to be compatible. When engaging in group communication, just as with interpersonal communication, we bring with us the intra-personal health of our individual selves as well as the interpersonal skills we have adopted with those in our life movie. Think about how the seven basic ingredients of the communication experience are enhanced when more than two individuals are contributing to the noise, decoding according to their particular viewpoints, and giving back different nonverbal feedback. The need to make room for the other person's reality is magnified within the small-group dynamic because most individuals have perceived and already solved the problem based on their personal reality and personal needs. For better or for worse, the hyper-individualistic culture we live in propagates a whole culture of people very adept at surface communication, conflict avoidance, and adopting passive-aggressive types of defense mechanisms. We experience little "blowups" in our communication environments every day due to the inability to make room for multiple points of view, and due to ineffective communication skills. We are taught to compete with one another more often than we are taught to work together for the greater good.

Daily we witness the stress many feel to make the grade. The desire to achieve a pat on the back often propagates self-centered ambitions. This is often compounded by the atmosphere of competition most workers thrive in. However, in spite of all this individualistic competition, we manage to maintain the institutions we thrive in with a modicum of success others wish to emulate. We are able to do this through the vision and abilities of those who lead their teams to a unified objective, realizing there is no "I" in team. We are able to do this because we are a nation of individuals who singularly desire to achieve their professional dreams and goals. Increasingly, the dynamics of the global village and global economy create interesting challenges for doing business worldwide. Why are some individuals extremely successful within the corporate or institutional dynamic while others appear to be stagnant, with no apparent vested interest? These leaders have a fundamental understanding that drives their decision-making skills. It is the understanding that effective communication practices are the keys to a successful organization. Show me an organization that does not have a structured, organized communication chart/flow and I will show you an organization that has failed or is failing.

So here you are within the department, the organization, trying to fit in, trying to be heard. The same personal issues that go into dyadic communication often surface in the group dynamic: insecurities, intrapersonal noise, prejudices, failure to perceive value in other perspectives, and so on. The more points of view that have to be considered in the discussion, the greater the need for problem-solving and conflict-management skills. Our families and communities do not offer enough positive examples of conflict resolution, and too much of what we experience is based on aggressive, win-lose patterns of resolution. A type of only-one-can-be-the-victor attitude. Most dredge up from the top of their lakes the same type of conflict-resolution skills they used as children or the same coping skills they mimicked from adults in their young lives. How can we have harmony within our institutions if we do not have harmony within ourselves, within our homes? We must all learn that "getting along" is a matter of setting aside personal points of view long enough to make room for the fact that there is always more than one way to approach any discussion, any solution. As within the interpersonal dynamic, critical listening and thinking skills are paramount to group communication.

Regardless of systems put in place designed to advance organizational goals, success lies solidly on the backs of those in leadership positions charged with the mandate to get the job done. How do leaders get the job done? Communication lies at the foundation of all effective leadership. This is the major reason this book brings communication-as-system to the forefront in examining organizational productivity. The aim is to understand the complexities of communication in all of its arenas and offer a more unifying approach as to how communication functions on all levels—internally and externally. The organizational leader must know and work to advance the institution within this framework.

In order to facilitate an effective communication climate, those responsible must take the steps to achieve their own level of comfort and skill. We are all familiar with the saying the "blind leading the blind." Too often those who lead organizations have not done the necessary homework to make sure their communication abilities and usage are not damaging to those they are trying to lead. What type of leader are you required to be? Organizations and groups need varying leadership styles. Maybe yours is a social group and needs only laissez-faire leadership—leadership that acts only to serve as an anchor, not necessarily a guide, a nonbinding glue that provides a common base. Or maybe you must exercise authoritarian leadership and consciously, vigorously direct your organization. You are the helm of the ship. Everyone takes their direction from your vision. Do you have one? Then there are groups that function more productively in democratic leadership environments. These organizations feel it necessary to allow most members to know they have a recognized individual contribution. Democratic leadership requires methods in place for including everyone at all levels of the organization in the creative and decision-making process. Unfortunately, there also times when abdacratic leadership exists, and that is basically no leadership at all. We witness many organizations fail from this problem. Regardless of the type of leadership mandated by your organization or group, you need to be prepared for the communication responsibility and expertise required to be an effective leader.

Warning

Leadership is who you are and not what you are.

How major a role does communication play concerning your leadership style? What is your leadership voice? Is it confident? Strong? Willing to admit mistakes and consider differing points of view? What about your tone? Review Chapter 2 and the section on paralanguage—understanding the impact of not what but how you say what you say. Volume, tone, pacing, dialect, and many other vocal characteristics play a role in how people perceive you, based on their conditioning. What type of language do you use? Your communication should be purposeful and affirming to yourself and those you are leading! Sincerely and with integrity, support those you can. Help to guide the others onward. Allow your "yes" to be yes and your "no" to be no. Your actions should be a direct reflection of your word. Your word should directly mirror your actions (see Application 4.3).

Become aware of your communication style and request feedback to assess this vital area of leadership. Adopt Leadership Communication practices that positively impact the company's health. Using intent-driven and esteem-building language is needed to replace communication that is toxic and ego damaging. Examples of intent-driven and supportive communication include:

Intent Driven | Esteem Building |

|---|---|

The organization WILL meet its goal of ... | Communicating as equals |

Employer and employees are working together ... | Proactive conflict resolution |

We are a team of multiple perspectives with common goals ... | Consistent praise |

Application 4.3 - Leadership Communication

Self-Monitoring Questions:

How would you judge your ability to communicate with those you have a responsibility to lead?

More importantly, how would they judge your ability to lead?

What type of leadership communication do you use?

Is there integrity associated with my word?

Are you affirming?

Do you have a strong sense of confidence about yourself and the company you are working for, so much that it shows to all who work with you?

Is there passion in your words and actions?

How is your self-talk?

With what intent do you face your employees each day?

How is your crisis communication?

Intent Driven | Esteem Building |

|---|---|

Our work together has furthered ... | Direct, clear feedback |

We will accomplish ... | Descriptive, I/we versus you |

Accepting the privileges and challenges of being a good leader requires that we use our communication expertise to always encourage productive, passion-filled organizational environments. Your thoughts, words, and actions create and support the leadership identity you determine.

Conflict is a reasonable expectation under any group dynamic. As discussed in Chapter 3, conflict is normal when two or more viewpoints have a vested interest in the outcome of a decision. One primary consideration of workplace conflict is that all members should have as their major concern the good of the organization. Ultimately, the decision that best advances the goal of the institution should prevail. A knowledgeable group leader skilled in conflict management and mediation will be able to move the group forward to the collective goal. There are a variety of group-conflict methods available for facilitators. Despite the different methodologies, most resolution patterns have as their basis the same precise steps:

Group Problem Solving Method

Defining the problem so that everyone is on the same page

Understanding the issues that comprise the problem

Reviewing group and organizational resources to solve the problem

Setting an agenda to gather information and resources to solve the problem

Applying a solution to remedy the problem

As long as members maintain a "team" attitude and bring their individual best for the collective good, the group should be able to come to a solution that is a consensus.

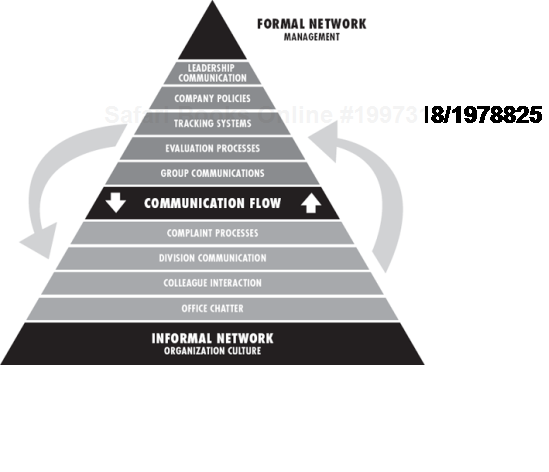

Within the organizational dynamic, we have formal and informal communication networks. These networks allow both structured and unstructured flow of communication, from management to labor, labor to management, coworker to coworker, and company to client. Formal structures include the company's policies, rules, tracking systems, evaluation processes, complaint processes, and all other aspects of communication as formally mandated through company policy. There is often a handbook that new employees receive to explain the formal communication process.

The informal structures are those that exist without benefit of policy, but they have just as much to do with the communication dynamics of the organization as the formal structures. Informal communication practices include discussions in the break room or cafeteria, at the water cooler or company picnic, the gossip that clarifies what really went on behind the closed doors, the chat with a colleague who can help you expedite some red tape. Any wise manager realizes that informal communication is just as important to the organizational dynamic as formal communication. A lot of what goes on is "heard through the grapevine." Often the informal communication acts as the "central nervous system" of the organization. A formal/informal communication flow chart may look something like the diagram in Figure 4.1.

There is a constant interplay between the areas of formal and informal networks. As a result, the communication environment must be managed in a way that takes into account both of these vital areas within the organization. Often, when conducting Communication Audits within an organization, we are surprised to find how much the information flowing from informal networks can positively or adversely affect the organizational context. From office chatter to lunchroom grapevines, communication travels through the network of the organization, impacting relationships, morale, and productivity. Become skilled at using both the formal and informal channels to learn from and influence the communication climate.

Depending on the formal or informal flow of communication, there are patterns of communication that will support your group communications in a more conducive manner than another pattern might. These patterns of information dissemination determine how individuals receive and use the information shared. Examine Figure 4.2 and notice the patterns that support a more formal climate versus a climate that is more social. The patterns are arranged from the most formal to the least formal, the most rigid structure to the least rigid structure.

Top down is the typical organizational hierarchical pattern: board of directors, president, VPs, managers, and on down, all vertical. This facilitates formal communication patterns. The forward pattern moves communication along a designed, formal line of information sharing. It carries the organization forward horizontally. Then the circle pattern broadens the outreach by widening the table of those allowed to participate; it tends more toward the informal, but is somewhat closed. The social pattern is an open, active network of exchange generally utilized for informal, social group discussions. It is important that the organization be aware of the various patterns of group communication and how these can function to advance the aim of effective communication. Choosing the appropriate communication pattern for a specific group experience can help facilitate positive group communication efforts.

Now let's return to the seven basic ingredients of dyadic communication and add the multiple perspectives you might experience in a meeting or a social gathering. These seven ingredients of sender, message, channel, situation, noise, listener, and feedback are very much a part of the group communication climate. Think about how the situation or setting affects the mood of communication. What about the time of day? How do you react to training first thing in the morning versus after lunch versus at the end of the day? These factors will greatly impact how you and others receive the message being communicated. Have you considered noise that could be cross-cultural in origin such as individualistic versus collective perspectives? Or group spatial relationships based on cultural socialization might determine who is comfortable next to whom. Are you adept at reading group feedback? It is important for the team leader to discern what type of internal noise may present itself at the meeting through the individual attendees. Being able to manipulate these simple but vital ingredients can make a huge difference in group communication effectiveness. Understanding the seven basic ingredients will increase your ease in communicating within a group effectively.

There are numerous problem-solving and conflict-resolution methods supporting successful group interaction and decision making. Successful group interaction is a complex mix of seven (7) elements: (1) healthy personal outlooks, (2) effective communication skills, (3) shared commitment to goals, (4) teamwork ethics, (5) group-communication ability, (6) maintenance tasks, and (7) conflict-management skills. A team must include members who are adept at group-communication practices. Effective facilitation is a skill. Make sure you have a good guidebook for templates of professional agendas, meeting checklists, technical and group needs, and minutes. The skilled use of parliamentary procedure is necessary to move forward respectful group interaction, decision making, and problem solving. Group methods such as brainstorming, roundtable discussions, buzz sessions, reflective critical thinking, committees, and other approaches do work when managed by knowledgeable facilitators.

Constructively examine your ability to work as part of a group whether its setting is personal, social, or professional. How are you doing? Can you see the connection between your personal self-worth and how you relate to others? We know that the mirror messages we receive within the group experience reflect the personal messages we send out. Have you written a script for your daily and long-term goals with the firm?

When conflicts arise, do you immediately get defensive, passive, antagonistic? Have you learned to deal with conflict constructively and maturely? These are skills most of us just do not have! Couple that lack with the high value we place on individualism, and it sometimes appears work life is a constant struggle of wills. However, the experience starts and ends with you. Remember, you bring you to the table. Make sure you are the team player you would want to work with. You can help create a communication environment that you and others can flourish in. It's just another scene in your life movie.

Productive and progressive membership is essential. Being a great team member requires your dedication to five (5) elements: (1) the goals of the group, (2) the ethical leadership of the group, (3) the team's membership, (4) the team's daily productivity, and (5) the harmony of the group. All groups go through the same basic steps when finding their synergy: coming together; resistance; conforming; and, lastly, stabilizing into their particular group dynamic. It takes time and commitment to effectively add to a team, but everyone can make a positive contribution. Make sure you know what you bring to the group dynamic. You have power to advance the group's mission. Maybe you have Influence Power, Information Power, Technical Power, Marketing Power, Logistics Power, Relationship Power, Stay-the-Course Power, etc. Find your power and add it to the mix! You do this by tapping into the thoughts, words, and actions that exemplify who you are. Find your voice! Your expert communication is the major contribution to the team's successful mission.

You have successfully maneuvered the first four steps of the Communication Staircase Model. After working to create the positive and productive self, you are now ready to face your public!

Warning

Bring your individual best to the collective good!

Q&A Small-Group/Organizational Communication

Q: | Dear PS, Employee morale is at an all-time low. We have suffered major organizational restructuring to prevent company closure. Many invested workers were given early release, and those who survived are sullen, fearful, even hostile. Any advice? |

A: | You of course realize that your organization is one of thousands experiencing the same concerns in this fragile global economy. Despite the need to push forward and demand everyone stay focused on the tasks at hand, your institution must take the time to assess and regain a supportive communication climate. Set up informal luncheon forums that allow everyone to be heard in an atmosphere of collective support. Keepers of the "suggestion box" should encourage and attend to voiced concerns. The major issue is to make sure all members see and experience a concerted effort on the part of management to acknowledge and be a part of the healing process in a way that works best for your organization. |

Q: | I am a small-group facilitator working with a group that is very diverse. I don't just mean ethnically, but all types of attitudes and cultural variations. To top it off, there are two coworkers in the group who have experienced unpleasant interaction in the past. |

A: | Group facilitation can be very challenging and should be undertaken by trained individuals. Make sure that you take advantage of professional-development opportunities in facilitation skills. The major thrust of any good group leadership is your belief and passion about the project. This will become infectious to the other members and encourage them to bring their individual best. Be careful to work on the maintenance needs of the group: interpersonal relationships, conflict management, praise, and intent communication. These habits will go a long way to defuse any hyper-individualistic tendencies. Make sure that concerns are immediately and openly addressed by the entire group. Use your expertise to keep members focused on tasks and not personalities. |

Q: | We have a member of our team who is downright lazy. I am tired of pulling this guy's weight. I tried to talk to the manager, but she keeps saying to give it some time. |

A: | Your group leader should take time to bring forward the unproductive member's team contribution. What is his talent, his passion? Can the team benefit from it? Team members should encourage support and input. Have you ever considered that there are those who need more support than others for a variety of reasons? Are we our brothers' keepers? A society prospers as it takes care of its widows, orphans, voiceless, and weak. Sometimes we will be required to go the extra mile. |

Q: | I never know what to say in a group. I always feel out of place. I try to be social, but I just don't feel comfortable. |

A: | Review the information shared in Chapter 1 on building your self-esteem and in Chapter 5 on the art of conversation. It is important to find your voice in any situation where you feel you want to contribute. The gift of gab does not belong to the few but is a learned art available to everyone. Build your self-confidence and your conversational repertoire. |

Q: | Q: My team never seems to be able to solve conflicts. We always get what I call "personality jammed." |

A: | This goes back to the basic premise of this chapter: finding a balance between the hyperindividualism that drives many in our culture and the need to become more collective in our group goals. Share the information in this chapter with the group leader and other members. Engage others in a discussion on the organizational values and mores that might be damaging to the group process, and the need to recognize the organization's ability to make adjustments to advance the goals of the group. |