1

Overview

Ryan first discovered the AND 1 mixtapes in the late 1990s. The mixtapes were a series of basketball “streetballing” videos, created by the popular basketball shoe and apparel company AND 1, that featured lightning-quick ball handling, acrobatic slam dunks, and jaw-dropping displays of individual talent. Ryan was a huge fan of the AND 1 mixtapes because the players used flashy, show-off moves that were very different from the more traditional style of basketball played in college or the NBA at the time. Ryan was so fascinated with the mixtapes that he even integrated them into his lesson plans when he worked as an English teacher in Zhejiang Province, China.

Many years later, Ryan was quite surprised to find out that AND 1’s cofounders, Jay Coen Gilbert and Bart Houlahan, along with Andrew Kassoy, their longtime friend and former Wall Street private equity investor, were the people who created the Certified B Corporation. Ryan learned that Coen Gilbert’s and Houlahan’s experiences at AND 1, and Kassoy’s experience on Wall Street, were central to their decision to get together to start B Lab, the nonprofit behind the B Corp movement.

AND 1 was a socially responsible business before the concept was well known, although AND 1 would not have identified with the term back then. AND 1’s shoes weren’t organic, local, or made from recycled tires, but the company had a basketball court at the office, on-site yoga classes, great parental leave benefits, and widely shared ownership of the company. Each year it gave 5 percent of its profits to local charities promoting high-quality urban education and youth leadership development. AND 1 also worked with its overseas factories to implement a best-in-class supplier code of conduct to ensure worker health and safety, fair wages, and professional development.

That was quite progressive for a basketball shoe company, especially because its target consumer was teenage basketball players, not conscious consumers with a large amount of disposable income. AND 1 was a company where employees were proud to work.

AND 1 was also successful financially. From a bootstrapped start-up in 1993 to modest revenues of $4 million in 1995, the company grew to more than $250 million in U.S. revenues by 2001. This meant that AND 1—in less than ten years—had risen to become the number two basketball shoe brand in the United States (behind Nike). As with many endeavors, however, success brought its own set of challenges.

AND 1 had taken on external investors in 1999. At the same time, the retail footwear and clothing industry was consolidating, which put pressure on AND 1’s margins. To make matters worse, Nike decided to put AND 1 in its crosshairs at its annual global sales meeting. Not surprisingly, this combination of external forces and some internal miscues led to a dip in sales and AND 1’s first-ever round of employee layoffs. After painfully getting the business back on track and considering their various options, Coen Gilbert, Houlahan, and their partners decided to put the company up for sale in 2005.

The results of the sale were immediate and difficult for Coen Gilbert and Houlahan to watch. Although the partners went into the sale process with eyes wide open, it was still heartbreaking for them to see all of the company’s preexisting commitments to its employees, overseas workers, and local community stripped away within a few months of the sale.

The Search for “What’s Next?”

In their journey from basketball (and Wall Street) to B Corps, Coen Gilbert, Houlahan, and Kassoy had a general sense of what they wanted to do next: the most good for as many people as possible for as long as possible. How this would manifest, however, was not initially clear.

Kassoy was increasingly inspired by his work with social entrepreneurs as a board member of Echoing Green (a private equity firm focused on social change) and the Freelancers Insurance Company (a future Certified B Corporation). Houlahan became inspired to develop best practices to support values-driven businesses that were seeking to raise capital, grow, and hold on to their socially and environmentally responsible missions. And Coen Gilbert, though proud of AND 1’s culture and practices, wanted to go much further, inspired by the stories of iconic socially responsible brands such as Ben & Jerry’s, Newman’s Own, and Patagonia, whose organizing principle seemed to be how to use business for good.

The three men’s initial, instinctive answer to the “What’s next?” question was to create a new company. Although AND 1 had a lot to be proud of, they reasoned, the company hadn’t been started with a specific intention to benefit society. What if they started a company with that intention? After discussing different approaches, however, Coen Gilbert, Houlahan, and Kassoy decided that they would be lucky to create a business as good as those created by existing social entrepreneurs such as Ahmed and Reem Rahim from Numi Organic Tea and Mike Hannigan and Sean Marx from Give Something Back Office Supplies. And more importantly, they decided that even if they could create such a business, one more business, no matter how big and effective, wouldn’t make a dent in addressing the world’s most pressing challenges.

They then thought about creating a social investment fund. Why build one company, they reasoned, when you could help build a dozen? That idea was also short lived. The three decided that even if they could be as effective as existing social venture funds such as Renewal Funds, RSF Social Finance, or SJF Ventures, a dozen fast-growing, innovative companies was still not adequate to address society’s challenges on a large scale.

What Coen Gilbert, Houlahan, and Kassoy discovered, after speaking with hundreds of entrepreneurs, investors, and thought leaders, was the need for two new basic elements to accelerate the growth of—and amplify the voice of—the entire socially and environmentally responsible business sector. This existing community of leaders said they needed a legal framework to help them grow while maintaining their original mission and values, and credible standards to help them distinguish their businesses in a crowded marketplace, where so many seemed to be making claims about being a “good” company.

To that end, in 2006 Coen Gilbert, Houlahan, and Kassoy cofounded B Lab, a nonprofit organization that serves a global movement of people using business as a force for good. The B Lab team worked with many leading businesses, investors, and attorneys to create a comprehensive set of performance and legal requirements—and they started certifying the first B Corporations in 2007.

I often wonder to what extent business can help society in its goals to alleviate poverty, preserve ecosystems, and build strong communities and institutions. . . . B Lab has proven that there is a way.

Madeleine Albright, former U.S. Secretary of State

B Corps: A Quick Overview

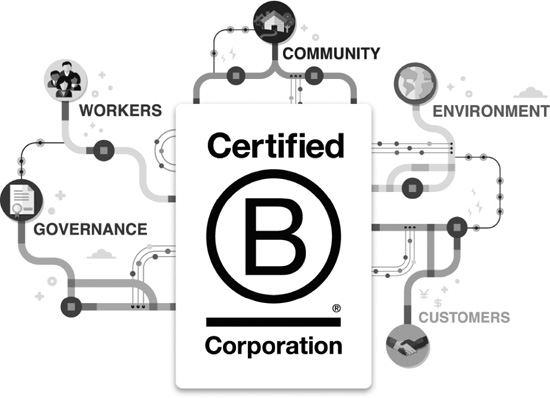

Certified B Corporations are companies that have been certified by the nonprofit B Lab to have met rigorous standards of social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency. B Corp certification is similar to Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification for green buildings, Fairtrade certification for coffee, or USDA Organic certification for milk. A key difference, however, is that B Corp certification is of an entire company and its practices (such as worker engagement, community involvement, environmental footprint, governance structure, and customer relationships) rather than looking at just one aspect of a company (such as the building or a product). This big picture evaluation is important because it helps distinguish between good companies and just good marketing.

Today, there is a growing global community of thousands of Certified B Corporations across hundreds of industries working together toward one unifying goal: to redefine success in business so that one day all companies will compete not just to be the best in the world but also to be the best for the world.

When we first heard about the B Corp movement, we said, “That’s what we’ve been trying to say and do this whole time!” It just fit with our approach and philosophy completely.

Alex Houlston, Energy for the People—Australia

As a quick overview, companies that wish to become Certified B Corporations must meet three basic requirements: verified social and environmental performance, legal accountability, and public transparency. Each of these steps, briefly outlined here, will be covered in more detail later in the book.

1. Verified social and environmental performance. To meet the performance requirement, a company must earn a minimum verified score of 80 points or above on the B Impact Assessment. The B Impact Assessment measures a company’s overall impact on its workers, community, customers, and the environment.

2. Legal accountability. Certified B Corporations are legally required to consider the impact of their decisions on all their stakeholders. The legal requirement can be fulfilled through a variety of structures, from the limited liability company (LLC) and traditional corporations to benefit corporations and cooperatives.

3. Public transparency. Transparency builds trust. All Certified B Corps must share their B Impact Report publicly on bcorporation.net. The B Impact Report is the summary of a company’s scores on the B Impact Assessment, by category, and contains no question-level information.

Nonprofits, such as 501(c)(3)s in the United States, and government agencies are not eligible to certify as B Corps. Companies with any of the following corporate structures may become Certified B Corps: benefit corporations, C corporations or S corporations, cooperatives, employee stock ownership plans, LLCs, low-profit limited liability companies (L3Cs), partnerships, sole proprietorships, wholly owned subsidiaries, or for-profit companies based outside the United States. This list is not exhaustive; see bcorporation.net for more details.

To finalize the B Corp certification process, prospective companies must sign the B Corp Declaration of Interdependence (a document outlining the values that define the B Corp community), sign a B Corp Agreement (a term sheet that defines the conditions and expectations of B Corp certification), and pay their annual certification fee (which is calculated based on a company’s annual sales). The certification term for B Corps is three years. After three years, companies are required to complete an updated B Impact Assessment and go through the verification process again in order to maintain their certification.

THE B ECONOMY IS BIGGER THAN B CORPS. B Lab collaborates across all sectors of society to build a global movement of people using business as a force for good.

The Emergence of the B Economy

One of the key concepts to develop since the publication of the first edition of The B Corp Handbook is the emergence of the “B Economy.” The B Economy is bigger than the community of Certified B Corps. For instance, the B Economy includes thousands of Certified B Corporations; thousands of benefit corporations; more than forty thousand companies that have used the B Impact Assessment to benchmark and improve their performance; the growing number of investors who are investing in Certified B Corps and benefit corporations; thousands of academics who are teaching about and conducting research on the B Corp movement; large companies that are using the assessment to improve the social and environmental performance of their company, their subsidiaries, and their suppliers; thousands of employees who work for any of the aforementioned enterprises; and millions of customers who buy from and support companies who are using business as a force for good.

The B Economy is important because it means that anyone—not just Certified B Corps—can participate in our broader movement. We will have succeeded when we no longer need a separate B Economy—just a global economy that aligns its activities toward creating a shared and durable prosperity for all.

What Do Investors Think about B Corps?

Many entrepreneurs want to know whether becoming a Certified B Corporation and/or a benefit corporation will hurt their ability to raise capital. The evidence says no. According to research compiled by B Lab, 120 venture capital firms have invested more than $2 billion in Certified B Corporations and benefit corporations.

For example, mainstream venture capitalists such as Andreessen Horowitz, GV, Kleiner Perkins, New Enterprise Associates, and Sequoia Capital have invested in Certified B Corporations. Union Square Ventures, a venture capital firm that invested in Kickstarter, says B Corps are appealing because the companies that produce the most stakeholder value over the next decade will also produce the best financial returns. Rick Alexander, head of legal policy at B Lab, has written, “Since nearly all B Corps are privately held companies, it would be reasonable to start by asking if venture capital firms invest in B Corps. They do. In fact, at this point, nearly every major Silicon Valley venture capital firm has invested in a B Corp.”1

Our B Corp certification is very important to our investors. It helps validate that we are making progress towards our goal of improving the livelihood of agribusinesses in developing nations.

Gabriel Mwendwa, Pearl Capital Partners—Uganda

Some of the Investors in Certified B Corps

Investor |

Certified B Corp |

Kohlberg Kravis Roberts |

Laureate Education |

Andreessen Horowitz |

Altschool |

Goldman Sachs |

Ripple Foods |

Union Square Ventures |

Kickstarter |

Greylock Partners |

Change.org |

New Enterprise Associates |

Cotopaxi |

Red Sea Ventures |

Allbirds |

Investeco |

Kuli Kuli |

Sequoia Capital |

Lemonade |

Obvious Ventures |

Olly |

Kleiner Perkins |

Recyclebank |

Foundry Group |

Schoolzilla |

Collaborative Fund |

Fishpeople |

Draper Fisher Jurvetson |

WaterSmart Software |

Tin Shed Ventures |

Bureo |

Force for Good Fund |

Spotlight: Girls |

White Road Investments |

Guayaki |

Silicon Valley Bank |

Singularity University |

Builders Fund |

Traditional Medicinals |

FreshTracks Capital |

SunCommon |

Does B Corp Work for Multinationals and Publicly Traded Companies?

Large companies, including multinationals and publicly traded companies, have many opportunities to take part in the growing B Economy. Some of these pathways include becoming a Certified B Corporation, incorporating as a benefit corporation, helping promote the movement to others, and using the B Impact Assessment and/or B Analytics to encourage key stakeholders to improve their social and environmental performance.

Another path to getting involved with the B Economy is to acquire a B Corp subsidiary. For example, Unilever, the consumer goods multinational, has gone on a recent spate of B Corp acquisitions. In 2016 and 2017, Unilever acquired five different Certified B Corps, including Mãe Terra, Pukka Herbs, Seventh Generation, Sir Kensington’s, and Sundial Brands. This was in addition to Ben & Jerry’s, which was acquired by Unilever in 2000 and became a Certified B Corp in 2012.

Other large multinationals, such as Anheuser-Busch, the Campbell Soup Company, Coca-Cola, Group Danone, the Hain Celestial Group, Nestlé, Procter & Gamble, Rakuten, SC Johnson & Son, and Vina Concha y Toro have acquired Certified B Corp subsidiaries in recent years.

Large Companies with B Corp Subsidiaries

Parent Company |

Certified B Corp Subsidiaries |

Anheuser-Busch |

4 Pines Brewing Company |

Azimut Group |

AZ Quest |

BancoEstado |

BancoEstado Microempresas, CajaVecina |

Campbell Soup Company |

Plum Organics, The Soulfull Project |

Coca-Cola |

Innocent Drinks |

Fairfax Financial |

The Redwoods Group |

Gap |

Athleta |

Group Danone |

Aguas Danone Argentina, Alpro, Danone AQUA Indonesia Danone Canada, Danone North America, Danone Spain, Danone UK, Earthbound Farm, Happy Family Brands, Les 2 Vaches |

Kikkoman |

Country Life |

Lactalis |

Stonyfield Farm |

Land O’Lakes |

Vermonta Creamery |

Nestlé |

Essential Living Foods, Garden of Life |

OppenheimerFunds Inc. |

SNW Asset Management |

Procter & Gamble |

New Chapter |

Rakuten |

OverDrive |

SC Johnson & Son |

People Against Dirty (Method, Ecover) |

The Hain Celestial Group |

Ella’s Kitchen UK |

Unilever |

Ben & Jerry’s, M÷e Terra, Pukka Herbs, Seventh Generation, Sir Kensington’s, Sundial Brands |

Vina Concha y Toro |

Fetzer Vineyards |

When we look at any of our acquisitions, one of the main considerations is always whether it is a good fit to Unilever. We look for companies that have similar vision and values to ours. That is critical to success of the partnership. B Corp companies come with many of the attributes that fit with our long-term goals and our culture, and therefore it is no surprise that some of our recent acquisitions, such as Seventh Generation, Pukka Herbs and Teas, and Sir Kensington, have been B Corps.

Paul Polman, Unilever—United Kingdom

Danone is a great example of a publicly traded multinational that is heavily involved with the B Corp movement on multiple levels. At the company’s 2017 annual shareholder meeting, Danone CEO Emmanuel Faber announced Danone’s intention to become the first Fortune 500 company to earn B Corp certification. In addition, once Danone decided to get more involved with the B Corp movement, the organization started helping several of its subsidiaries make progress toward B Corp certification. By using the B Impact Assessment, Danone was able to determine which subsidiaries were ready to move toward certification and which first needed focused improvement work.

“The B Impact Assessment represents a set of demanding standards, which some of our businesses are able to meet already,” explains Blandine Stefani, B Corp community director at Danone. “For some others, becoming a Certified B Corp is an ambition that will require some changes to their practices, with the support of B Lab.” Through a cohort process facilitated by B Lab, the subsidiaries completed the B Impact Assessment together, allowing Danone to monitor their progress and improvement using B Lab’s B Analytics tool. For a large company like Danone, the Impact Management Cohort made pursuing B Corp certification for subsidiaries easier, faster, and more transparent.

As of 2018, Danone has nine subsidiaries certified as B Corps, is making use of the benefit corporation legal structure in the United States, is assessing and educating more business units using B Lab’s impact management tools, and is taking a leadership role to create more pathways for multinational engagement.

In an innovative approach tying the cost of capital to environmental, social, and governance benchmarks, Danone partnered with twelve leading global banks that agreed to lower their loan rates if Danone increases its verified positive impact in the world. The percentage of Danone’s sales from Certified B Corp subsidiaries was one of the environmental, social, and governance measurements. In other words, the more they sell from subsidiaries that are B Corps, the lower their cost of capital.

The deal on Danone’s $2 billion syndicated credit facility was led by BNP Paribas and includes Barclays, Citibank, Crédit Agricole, HSBC, ING, JPMorgan, MUFG, Natixis, NatWest, Santander, and Société Générale. The result is that the heads of corporate and institutional banking for a dozen of the world’s largest credit providers—notoriously the most fiscally conservative people in any boardroom—have affirmed that becoming a Certified B Corporation reduces risk and can help you save money.