CHAPTER 13

THE SYSTEMS LEADER: DRIVING CONSTANT PROGRESS ON BRAINS AND BRAWN

If you were filling your own job today, would you rehire yourself? Are you the best person for the role now, rather than when you first got the job? If you’re no longer the best person, what are you going to do about it?

—Katrina Lake, Executive Chairperson of Stitch Fix

I teach the Brains and Brawn framework to audiences all over the world, from huge multinational companies to start-ups on almost every continent. Whenever I finish a presentation about these ideas, the question I hear most often is, “I get it, but where do I start?” People say that the opportunities are exciting, but the challenges of acting on them sometimes seem overwhelming. I respond by urging the audience to start by asking themselves four key questions:

1. What does the trend of combining digital and physical mean for your customers and their businesses?

2. How can your company’s core technologies and relationships provide an advantage against the competition?

3. What products and services do your customers need that you are not currently delivering?

4. How can you stand out as a leader by widening your perspective, seeing the context, and embracing risk during times of rapid change?

These questions get to the heart of Systems Leadership, a phrase you’ve seen throughout this book, including in the “notebook” sections of the 10 previous chapters (Parts II and III). It’s my term for the art and science of maximizing both the Brains and Brawn of an organization. In this final chapter, let’s get more specific about exactly what Systems Leadership means, how you can get better at it, and how it relates to the Brains and Brawn competencies. Then let’s look at two outstanding Systems Leaders who demonstrate the need for driving constant progress at two very different companies: Katrina Lake of Stitch Fix and Julie Sweet of Accenture.

The Urgency of Systems Leadership

I define Systems Leadership as the ability to master processes and strategies from different perspectives at the same time: physical and digital, breadth of market and depth of market, short term and long term, what’s good for the company and what’s good for its ecosystem. Systems Leaders combine the IQ to understand their company’s technology and business model with the EQ to build effective teams and inspire them to new heights. They use short-term execution skills to hit their financial targets this year, while also driving changes that may not pay off for five years. They grasp the big picture and essential details simultaneously. They understand how all the elements of an organization affect both internal and external stakeholders, and how interactions internally and externally shape a company’s outcomes.

When I described Systems Leadership to one Fortune 500 CEO, his response was, “Wow, that sounds hard.” He was right, of course. But Systems Leadership is hard in the same sense that running a marathon, playing guitar, doing calculus, or driving on a highway are hard. For all of those competencies, the baseline of required innate talents isn’t exceptionally rare. The key is putting in the consistent effort over time to learn and then master the right skills. It’s about practice much more than talent.

If you’ve read this far into the book, I have no doubt that you have the intellectual and emotional right stuff to become a Systems Leader. But you have to choose to commit to that goal, because it will make a massive difference to your career. It can determine whether you’ll rise as far as your talents can take you or get stuck along the way. And whether you work for a large incumbent or a small upstart, your mastery of Systems Leadership and the 10 Brains and Brawn competencies can determine your organization’s success or failure. The stakes are that high.

Systems Leadership Versus Traditional Leadership

Traditionally, executives rose to senior management through expertise in one particular function, usually operations, engineering, sales, marketing, or finance. When put in charge of a business unit or a whole company, their backgrounds naturally biased them toward seeing the landscape through one primary perspective. To cover everything else, they tended to rely heavily on colleagues who were experts in other functions, including groups like R&D, human resources, legal, and government relations. Leaders could set broad goals, delegate the details, and assume that things would work out, as long as they had a competent team. There was no need to be immersed in every department’s details.

But the complexity of modern business makes that dynamic outdated. Every internal function is more interdependent than ever; for instance, a small shift in the sales department’s strategy can wreak havoc on manufacturing and finance, and vice versa. Moreover, every player in a company’s external ecosystem of partners, competitors, and customers can shake up carefully laid plans at any moment. As a result, today’s leaders need a much broader range of expertise and skills, compared to their predecessors. They need to be good at fitting all these pieces together to deliver optimal value to customers and shareholders.

This is not to imply that you need to be omniscient or memorize every detail of every aspect of your business. No one can possibly do that. But you need to learn enough to have meaningful conversations with experts of all stripes. You need to know enough to ask the right questions, not necessarily to answer them. Then you need to consider what you’re learning from those experts and how their perspectives fit into the bigger picture of your company’s strategic priorities and those of your ecosystem partners. Finally, you’ll need the self-confidence and courage to make decisions under extreme uncertainty, because trying to play it safe and stick to the status quo can lead to disaster.

To develop that breadth of knowledge, you’ll have to commit to lifelong learning and a constant openness to new experiences. That might mean anything from reading articles about artificial intelligence to buying coffee for colleagues you’ve never spoken to before to setting up a TikTok account so you can understand Generation Z. Above all, it means breaking out of your information bubbles—resisting the urge to stick with people from the same background as you, who see the world the same way you do.

A Synthesis of Two Kinds of Thinking

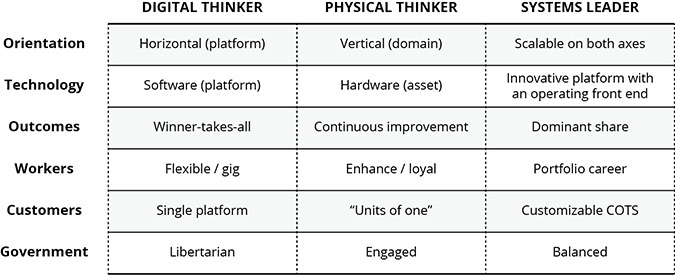

Table 13.1 offers a quick-and-dirty way to compare the stereotypes of a Silicon Valley/digital leader (left), a traditional/industrial leader (center), and a Systems Leader. Let’s consider each of them in terms of six challenges.

TABLE 13.1 Duality of the Systems Leader

Digital thinkers are obsessed with building a horizontal platform that can scale to infinity. For instance, Facebook won’t be satisfied until every human on the planet is using a Facebook product; the first 2.5 billion don’t even represent the halfway point. The next row follows logically; digital thinkers prefer software over hardware because it’s so much easier to scale than any physical product. Their ideal outcome is winner take all, because digital markets tend to settle on one dominant player (Google in search, Uber in ride-sharing, etc.). Their ideal workers are flexible—either gig-based or the kind of people who change jobs every year or two, if they start to get restless. Their ideal customers are happy with a single basic offering, which also makes scaling easier. And their ideal government is libertarian, imposing minimal regulations or interference in private markets.

Physical thinkers have very different priorities and values, from top to bottom. They generally have domain expertise in a particular area, so they focus on vertical success—building great products for a narrow but deep market, such as Mercedes owners. Vertical success is often hardware-based, and outcomes are often framed around continuous improvement. For instance, if Burger King’s revenue growth outpaces the growth of McDonald’s and Wendy’s by 2 percent, that’s a huge year. Historically, if General Motors made a Chevy 2 percent more fuel efficient or 5 percent faster, that was a victory. Physical thinkers try to inspire employees to stay with an organization for many years, to reap the benefits of institutional memory. They think about customers as “units of one” who prefer customized solutions; the company’s goal is to provide distinctive solutions that lock customers in. And they see nothing wrong with government rules and regulations if they can turn their mastery of government relations into a competitive advantage.

Systems Leaders combine both sets of skills and mindsets. They understand and appreciate both hardware and software, both vertical expertise and horizontal scale. They aren’t hell-bent on achieving Amazon-like winner-take-all dominance, but they want bigger outcomes than fighting for each fraction of a point of market share. They try to build employee loyalty through various benefits (financial and emotional) but understand that almost no one has decades-long careers at a single company anymore. Their ideal customers seek a “customizable off the shelf” (COTS) solution that can easily be tweaked to individual needs. (Think of the Netflix algorithms that make a sci-fi fan’s browsing experience so different from a rom-com fan’s.) And Systems Leaders see the ideal government as balanced—regulating products and protecting workers where appropriate, but never overregulating in ways that inhibit innovation or hurt customers.

The Orchestra Conductor Without a Score

It helps to imagine a Systems Leader as an orchestra conductor, surrounded not only by all the functions within the company but also by external forces such as demanding customers, aggressive competitors, and unreliable ecosystem partners. Most conductors come from a background of expertise on a single instrument, but when they move to the podium, they have to widen their perspective. Good conductors retune their ears to take in all the instruments at once and get them all working in harmony. The metaphor breaks down, however, because a conductor has a score that spells out exactly how every instrument should be contributing to the piece. But a Systems Leader operates in a state of constant uncertainty about what will happen next, and while not having a score, knows the basic tune and needs to inspire the team to play the music harmoniously together.

Systems Leaders rely on their ability to recognize patterns and apply past experiences to new situations. They combine the clarity to focus on improving the lives and fortunes of their customers with the courage to lead their people into the unknown. The next five sections will show how these daring conductors get the best performance out of every section of the orchestra, without allowing the overall sound to collapse in cacophony.

Operating at Intersections

Operating at intersections means pursuing two or more goals at the same time, because you know that succeeding at each of them will delivery powerful synergies that you couldn’t get from them separately. This skill underpins many of the Brains and Brawn competencies that we’ve explored.

There can be multiple types of intersections:

![]() An innovative technology meets an innovative business model. This powerful combination drives some of the most successful companies of our time, including many of the examples in the previous chapters. For instance, think of how Align blended cutting-edge technology (digital scanners and 3D printers) with an innovative business model (making dentists a channel partner to offer orthodonture to adults) to deliver an appealing customer benefit (straight teeth through a convenient, affordable, nearly invisible process). Align might have succeeded with its new technology alone or with its new business model alone, but the synergy was orders of magnitude more valuable.

An innovative technology meets an innovative business model. This powerful combination drives some of the most successful companies of our time, including many of the examples in the previous chapters. For instance, think of how Align blended cutting-edge technology (digital scanners and 3D printers) with an innovative business model (making dentists a channel partner to offer orthodonture to adults) to deliver an appealing customer benefit (straight teeth through a convenient, affordable, nearly invisible process). Align might have succeeded with its new technology alone or with its new business model alone, but the synergy was orders of magnitude more valuable.

![]() Short-term results meet long-term change. In the old days, companies would elevate leaders who were great at running a business unit according to its plan and hitting its quarterly and annual targets. The company might also celebrate visionary thinkers who could plot new strategies for 5 or 10 years out. But operators and innovators were treated as separate groups with very different skill sets. Today, in contrast, Systems Leaders know how to operate at scale and know how to manage innovation. In fact, they find their greatest satisfaction at that intersection. Think of Pedro Earp at AB InBev, trying to maximize today’s microbrew brands while experimenting with bold new ways to deliver beer to future customers.

Short-term results meet long-term change. In the old days, companies would elevate leaders who were great at running a business unit according to its plan and hitting its quarterly and annual targets. The company might also celebrate visionary thinkers who could plot new strategies for 5 or 10 years out. But operators and innovators were treated as separate groups with very different skill sets. Today, in contrast, Systems Leaders know how to operate at scale and know how to manage innovation. In fact, they find their greatest satisfaction at that intersection. Think of Pedro Earp at AB InBev, trying to maximize today’s microbrew brands while experimenting with bold new ways to deliver beer to future customers.

![]() Global strength meets local expertise. To make the most of both assets in a challenging market, think of how Michelin developed its “glocal” strategy in China to compete against low-cost Chinese tire producers. It found a sweet spot of quality and price that neither its fellow global giants nor its local Chinese rivals could match.

Global strength meets local expertise. To make the most of both assets in a challenging market, think of how Michelin developed its “glocal” strategy in China to compete against low-cost Chinese tire producers. It found a sweet spot of quality and price that neither its fellow global giants nor its local Chinese rivals could match.

Sometimes operating at intersections means spotting connections between disparate businesses that aren’t obvious between seemingly disparate businesses. Think of how Samsung realized that its manufacturing process for semiconductors, which requires clean rooms, lots of capital equipment, and strong operational discipline, is similar to the process for manufacturing pharmaceuticals. The company’s leaders concluded that their competencies in one industry could be applied to a radically different one. Today, improbably, Samsung is the world’s largest manufacturer of generic biologic drugs.

Systems Leaders constantly scan the horizon for potential intersections between “what we’re already good at” and “what else we might be able to do with these skills.”

Predicting the Future and Preparing for It

You don’t need to be a professional futurist to know which technologies are going to continue to impact business and society for at least the next decade, among them robotics, data analytics, artificial intelligence, machine learning, cloud computing, blockchain, and additive manufacturing. The challenge is figuring out how those and other innovations will affect various aspects of your organization, including core functions like administration, R&D, sales, and manufacturing. Like it or not, certain jobs in all of those areas will become obsolete, while new jobs will be created in areas as yet undreamed of.

These unavoidable trends force Systems Leaders to make tough decisions, the sooner the better. Their inner ears help them figure out what a company should produce itself and what should it buy from suppliers. Their muscles help them build scale intelligently, staffing up or retraining employees to replace the ones whose old jobs are going away. Their prefrontal cortexes help them weigh the risk of making too many changes too quickly against the risk of being left behind in the industry in 5 or 10 years.

As you make these tough decisions about the future, be mindful of the biases you’ve developed over your career. There’s nothing shameful about being biased, as long as you’re self-aware enough to recognize when you might be wrong. For instance, I was trained as a business unit operator at companies like Intel and GE, and as an executive and CEO at Silicon Valley start-ups, so I look at opportunities from an operating perspective. People who trained as engineers, accountants, sales reps, or lawyers will see the world differently.

Another pitfall to avoid when predicting the future is groupthink. One of my favorite aphorisms comes from Carl Ice, the recently retired CEO of BNSF Railway: “You’re never wrong in your own conference room.” Systems Leaders seek outside opinions from trusted sources beyond their direct reports. They get out of the office regularly to visit remote facilities or meet with informal advisors, or ideally both. Ice told my class that every year he rode at least 12,000 miles on his railroad, so he could see firsthand the condition of its operations.1 Anyone insightful enough to understand the industry and honest enough to challenge the leader’s conclusions can become a valuable sounding board or devil’s advocate.

Managing Context

Context is defined as “the circumstances that form the setting for an event, statement, or idea, in terms of which it can be fully understood and assessed.”2 Facts in isolation are not truth; they can lead you badly astray if you misunderstand their context. To emphasize this point, I often show my classes a slide with a simple equation that I learned from my co-teacher at Stanford and former GE CEO, Jeff Immelt:

Truth = Facts + Context

Here’s an example of what happens when context changes. During the 1980s, most American business leaders saw globalization as a virtually unambiguous good, a way to sell more stuff around the world while reducing supply costs and (via offshoring) labor costs. But over the last decade, while the fundamentals of global free trade have remained basically the same, the context is now different. China has become a rising global superpower, not just a place to make sneakers or cell phones cheaply. Offshoring has devastated large parts of the industrial Midwest in the United States, leading to the opioid crisis and extreme populist politics, among other consequences. Even Germany, whose largest trading partner is China, is now seeing unexpected competition from Chinese companies.3 Rather than rushing into new avenues for globalization that seem beneficial on the surface, Systems Leaders take time to consider the wider context.

Another example of managing context came up when I was teaching a case study about social media. I asked the room why Facebook has become widely hated in recent years, while its fellow tech giant Google—which also tracks and monetizes the actions of its users—has avoided that kind of visceral negative reaction. My students were stumped, until a guest speaker noted that Google’s declared mission is organizing the world’s information to help you find whatever you want. If a Google search helps you find something, Google doesn’t care whether the information lives on its own site or somewhere else. Their goal is to be helpful enough that you’ll want to return, not to lure you into a walled garden of content for hours every day. In other words, the facts of Facebook’s business model sound great for Facebook: users get addicted to consuming and sharing content, which makes the platform more effective for highly targeted advertising. It’s only when you consider the context of user resentment and feelings of exploitation that the long-term dangers of that model become clear.

Systems Leaders think about the context of every message they share with staff, via any medium. They never forget that risk and uncertainty can scare the hell out of their people. Asking them to change the way they’ve been operating for years is much more effective when done with a tone of quiet determination, not panic. A context of reassurance and calm can go a long way, even if you feel the opposite of calm inside. Trying to explain something by saying, “We have to make this change for these reasons, we know how to do it, let’s get started,” is a powerful way to drive change.

The Product Manager Mindset

Systems Leaders who start from a background in finance, sales, marketing, or other nontechnical functions often need to put in extra effort to become well-versed in their company’s technology. It’s worth the time to do extra reading and other research to be able to have well-informed, peer-to-peer discussions with the people who actually sling code and design machines. Former Nokia Chairman Risto Siilasmaa wrote about why he took courses on AI and machine learning: “As a long-term CEO, I’d gotten used to having things explained to me. Somebody else does the hard work and I can focus on figuring out the right questions. Sometimes CEOs and Chairmen may feel that understanding the nuts and bolts of technology is in some way beneath their role, that it’s enough for them to focus on ‘creating shareholder value.’ Alternatively, they may feel that they can’t learn something seemingly complicated and therefore don’t consider trying. Neither one is the entrepreneurial way.”4

The combination of learning, listening, and showing empathy to experts adds up to what I call the product manager mindset. In many companies, the product manager is at the hub of a wheel-shaped org chart, constantly interacting with engineering, customers, manufacturing, sales, finance, research, and other departments. It sounds like a fun, interdisciplinary job, but (at least in Silicon Valley) it’s actually very tough. You’re responsible for everything related to your product, but you have no direct control over the people who can make or break its success. The key skills are interpersonal: learning how to get along with different personality types in all those functions. Systems Leaders listen closely to what those experts need and whatever problems they may spot before the rest of the organization. The goal is to become a polymorph who can fit into any internal subculture, winning the respect of the natives.5 A great product manager will have everyone supporting her, saying things like, “She understands what we need and fights to get it for us.”

Systems Leaders usually have more operational authority than product managers, so they can’t complain about being accountable for everything while owning nothing. Nevertheless, it pays huge dividends to think like a product manager. Dive deeply into the technologies that underpin your products and your company’s ecosystem. Listen closely to experts and use your amygdala to show empathy for their concerns. When you have to make a decision that upsets certain factions, your strong relationships—“she’s one of us”—will soften the blow.

Going “Risk on” During Uncertainty and Disruption

Financial theory says that in times of exceptional volatility, you should become extra cautious and adopt a “risk off” mindset. But Systems Leaders generally have the opposite impulse. The more disruptive their situation, the more they go “risk on” and confront the source of the challenge, rather than passively waiting to see how things play out in their company or industry. They learn how to manage their own anxiety and that of their teams. The Systems Leaders we’ve met in this book, from both disruptors like Stripe and incumbents like John Deere, have applied their prefrontal cortexes and summoned their courage for untested, risky strategies.

One tactic for leading through uncertainty is to watch how you spend your time, because your people are definitely watching. Your actions send a clear signal to the organization about what you consider important, regardless of what you might say in a speech or email blast. Intel’s iconic CEO Andy Grove proved this in his classic book Only the Paranoid Survive, when he reprinted a week from the desk calendar of the CEO of a large multinational during a significant corporate inflection point. This leader allowed his time to be filled with lots of nonessential meetings and factory tours, while ignoring the crisis at hand.6

Another tactic to be mindful of is the difference between skill and luck. If you look at your career history, were all of your past successes really dependent on your talents and hard work? Or were you just in the right place at the right time for some key opportunities? Acknowledging the role of luck won’t diminish your accomplishments, but it will inoculate you against hubris. As Warren Buffett famously said, “You never know who’s swimming naked until the tide goes out.” That applies to lucky business leaders as well as lucky wealth managers.

Now let’s conclude by looking at two Systems Leaders who exemplify all of these mindsets and attributes.

Katrina Lake: Shaking Up the Fashion Retail Business

Katrina Lake, the founder and Executive Chairperson of online retailer Stitch Fix, is an expert on disruptive change. She first took on a crowded market in 2011 by launching a new kind of personal shopping advice service. Instead of going to a fancy boutique for help in picking out clothes, Stitch Fix customers could simply fill out a survey about their tastes and then let a human stylist, supported by an AI algorithm, make suggestions. The stylist would send a five-item “fix” and the customer could decide how many to keep and how many to send back in a prepaid, preaddressed return envelope. As of early 2021, the company has sold $6 billion worth of clothing in its first decade, entirely sight unseen, and its average customer spends $500 in the first year.7

As the New York Times noted in May 2017, “The retail landscape is littered with the casualties of changing consumer behavior. Shoppers are bargain hunting online, department stores are struggling, and once-mainstay brands are closing out permanently. Then there is Stitch Fix, a mail-order clothing service that offers customers little choice in what garments they receive, and shies away from discounts for brand name dresses, pants, and accessories. Despite a business model that seems to defy conventional wisdom, Stitch Fix continues to grow.”8

Although Lake was initially rejected by about 50 skeptical venture capitalists, the company had a successful IPO in November 2017, making her the youngest woman ever to take a start-up public. She has become an icon in Silicon Valley for building an innovative disruptor in the face of fierce competition. She displays the appealing blend of self-confidence and self-awareness that most Systems Leaders share, which immediately became apparent when she visited my class in April 2019 and again in January 2021.

Lake can speak with sophistication and depth about all the major aspects of her business, including fashion, big data, AI, branding, marketing, and workplace culture. She obsesses about the big picture of Stitch Fix’s ecosystem as well as the smallest details of its products and services. As Lake and her team have expanded the company to serve new markets and demographics (such as men and children), she is determined to maintain its biggest competitive advantage: a unique blend of analytics, fashion, and customer service, driving a unique shopping experience.

Lake pointed out that the Stitch Fix system enables customers to give extremely detailed feedback on the clothes that they both do and do not choose to purchase, with specific questions about fit (allowing customers to provide input on items such as the placement of the first button in a shirt or blouse, where the back pockets sit on a body for a pair of jeans, etc.), in a manner that no physical retailer could match. Not even Amazon would have this level detail if it chose to offer a similar clothing service. Stitch Fix uses all this data not only to make better suggestions to customers, but also to feed information back to 1,000+ clothing brands so they can improve their products.

Stitch Fix blends a horizontally scalable business with enough customization to hold onto customers over time. The uniquely personalized recommendations made by the company’s 3,000+ stylists get more and more accurate as people continue to use the service and provide more feedback. This combination of scale and intimacy make it nearly impossible for any clothing retailer to copy the Stitch Fix model without a massive restructuring of their businesses.

Rather than rest on that competitive advantage, Lake always seeks improvement on all fronts. She believes that personal growth correlates directly to company growth; if a company has grown by 40 percent, its people need to ask themselves if they’ve also grown by 40 percent. Other questions she asks herself and her leadership team every couple of years: “If you were filling your own job today, would you rehire yourself? Are you the best person for the role now, rather than when you first got the job? If you’re no longer the best person, what are you going to do about it?” These conversations are often uncomfortable, especially if someone has been great at whatever got them to their current position, but now needs new skills for a changing business. But they’re a powerful way to drive professional development.

When Lake stressed the importance of hiring a diverse team, she framed it in an unusual way. Instead of merely seeking demographic diversity, she also evaluates potential new hires on whether they will become a “cultural fit” or (preferably) a “cultural add.” She believes that any organization that brings in only new people who reflect the existing culture and values—even if they reflect diversity of gender, ethnicity, age, and so on—will risk groupthink and blind spots.

Stitch Fix is a hybrid of Brains and Brawn, blending innovative algorithms, skillful use of big data, the empathy of its human stylists, and the strong spine of its logistics as it sends millions of pieces of clothing back and forth. The company’s rapid growth stems in large part from Lake’s willingness to go “risk on” rather than avoiding hard decisions, and the company has thrived with their model during the pandemic as other retail brands have struggled. She knows that moving toward disruption is the best way to avoid becoming a passive receiver of new technologies and trends. It will also give Stitch Fix stamina to help ward off future disruptions that can’t even be imagined yet.

As I approached the end of writing this book, Lake came back to my class at Stanford for a second visit. This conversation with students was a challenge, with some in the class being big fans of the company, while others were skeptical of Stitch Fix’s long-term differentiated potential. Lake remained resolute and passionate about the many opportunities available for the company’s future, but shortly after the session took place, she changed her role from CEO to Executive Chairperson. The continuing evolution of the fashion retail segment continues to confront even successful disruptors such as Lake and her team. Systems Leaders can never declare a permanent victory, because competitors, markets and customers never stop changing, sometimes in unexpected directions. Nothing can detract from Lake’s success in building a groundbreaking company, but every new day presents new potential threats, whether from Amazon or a previously unknown start-up.

Julie Sweet: Reinventing a Brawny Consulting Giant

Accenture has come a long way since the early 1950s, with origins that trace back to the accounting firm Arthur Andersen. In 1989, Arthur Andersen and Andersen Consulting were established as separate business units and legal entities with a shared owner, with a profit-sharing arrangement that led to tensions between them. The two formally broke ties in 2000 after an arbitration settlement, and Andersen Consulting took on its new name in 2001—just in time to avoid being tarnished by the Enron accounting scandal, which destroyed Arthur Andersen.9

Two decades later, Accenture is a giant player in technology-driven consulting, with $44.3 billion in annual revenue generated by its 514,000 employees, who are located in 51 countries and serve clients in 120 countries.10 If any company needs help figuring out its IT strategy, cloud services, global systems integration, information security, or even supporting vertical areas such as digital advertising or building more stable supply chains and reinventing manufacturing and operations, there’s a good chance it will reach out to Accenture. But the road to that strong position has been tough.

Julie Sweet spoke to my class in February 2019, a few months before she was promoted from North American CEO to worldwide CEO. She had joined Accenture as general counsel in 2010; her legal background gave her a rare and valuable perspective in a company filled with engineers and MBAs. During her first decade at the firm, Sweet played an integral role as a member of the global management team, running Accenture’s largest market starting in 2015 and contributing to a dramatic expansion and transformation of its services—from primarily a back-end integrator of existing technologies to a pioneer of cutting-edge artificial intelligence, security, cloud storage, quantum computing, and even advertising technology. In Silicon Valley jargon, Accenture has “moved up the technical stack” to offer its clients more sophisticated and valuable services.

Sweet now leads Accenture’s ongoing evolution by combining the essential skills of a Systems Leader: predicting and preparing for the future, adopting a product manager mindset, managing the context of her changing ecosystem, and staying calm in the face of tough competition. She has leveraged Accenture’s brawny size and scale (muscles) to expand into many new kinds of services, operating glocally in those 120 countries. She blends a strong focus on Accenture’s core mission of serving clients with an openness to changing anything else—including its org chart, success metrics, and compensation practices. She continually expands her knowledge of new domains, such as advertising, to be able to serve new kinds of clients. And she’s been willing to part ways with senior leaders who weren’t willing to adapt and grow during Accenture’s reinvention.

As Sweet told my class in 2019, “Everything about the services we provide to our clients has changed. Eight years ago, we were less than 10 percent doing digital, cloud, and security. Today it’s over 60 percent. And in order to drive that, we’ve fundamentally transformed all of Accenture. The most fundamental change is the mindset. Eight years ago, we were very proud of being fast followers and light on investment. Today, we’re an innovation-led company and we deeply invest in skills and capabilities.”11

Accenture has found creative ways to redevelop talent within its existing workforce. For instance, instead of hiring tens of thousands of new employees to deliver more advanced services, Accenture started challenging employees to automate their own jobs. They went through training programs to master new skills, then graduated by showing how to automate their old jobs before being promoted into new roles. By gamifying this process, Sweet told us, Accenture has since retrained more than 300,000 workers in digital, cloud, and security, and continues to push continuous learning while retaining institutional knowledge.

Another great example of driving change is how Accenture became an unlikely leader in digital advertising. As the Wall Street Journal reported in 2018, consumer products giants such as Unilever have shifted their advertising focus from Mad Men–style creative campaigns toward data-driven analytics and sophisticated online targeting. Accenture set up an interactive practice to offer those services with a focus on designing and running great experiences, and to compete with major ad agencies. As the head of its interactive marketing group told the Journal, Accenture might not be the place to go for a clever car commercial, but it has the expertise to help an automaker reinvent its entire car-buying experience.12

Sweet explained, “You have to put together a deep understanding of technology with the use of artificial intelligence and analytics to understand the customer. It’s not simply one skill set. And that’s what makes Accenture so unique.”13 She also stressed the diversity of talent required to branch out into new markets. “Accenture Interactive is now the largest digital ad agency in the world. Those individuals tend to work in studios. They work very differently. We’re quite proud of the fact that we have a ‘culture of cultures’ that come together to serve our clients.”14

Sweet also has a strong inner ear for balancing ownership and partnership. The firm depends on maintaining healthy relationships with everyone from software giants like SAP, Oracle, and Microsoft to smaller players like Appian, a low-code platform that automates operations—which in the life sciences industry enables companies to focus on biopharma innovation. Accenture comments on its website about partnering “with a vast set of leading ecosystem partners to help push the boundaries of what technology can enable for your business.”15 Links to hundreds of companies follow. Organizing this huge ecosystem requires strong hand-eye coordination and a keen appreciation for context. Accenture constantly has to decide which areas it should compete in and which it should leave to its partners. Sweet believes that the best way to serve Accenture’s clients is to bring them the best possible technology, even if it comes via a third-party.

In October 2020, Fortune ranked Sweet number one on its annual list of the most powerful women in business, noting that Accenture’s profit had risen 7 percent in her first year as CEO and that “Sweet steered Accenture’s more than half a million employees in 51 countries through the pandemic, a crisis that has made the firm’s skills more essential than ever. . . . As COVID-19 hit, the company tapped into that expertise to help connect the UK’s 1.2 million National Health Service workers remotely and to partner with Salesforce on contact tracing and vaccine management technology.”16

If Accenture could thrive even during a global pandemic, its future as a hybrid Brains and Brawn company seems bright indeed.

The New World of Digital and Physical

I’m completing this book at the beginning of 2021, after a year that has turned all the popular clichés about disruption, uncertainty, and rapid change into laughable understatements. Last January, I wondered whether the headlines about a new virus in China would amount to anything significant. By December, I felt like a veteran of distance learning, routinely delivering virtual lectures and conducting workshops from my home office to executives and students as far away as Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur, Rio de Janeiro, London, Riyadh, Stockholm, and Chicago. I’ve continued to upgrade my home office with a high-resolution 4K camera, studio lighting, and an improved sound system.

While I can’t predict exactly what the “new normal” will fully encompass once the pandemic is behind us, I do know that there will be no going back to a world of solely in-person presentations and flying around for speeches and meetings. Today, I am able to communicate and deliver compelling, interactive education experiences using technology to cross thousands of miles. These new solutions are too effective and efficient to disappear completely. Going forward, I expect to be doing a blend of both in-person and online meetings and events, choosing the appropriate format as needed.

My future, like yours, will surely be a hybrid of the best aspects of digital and physical, virtual and in-person, innovation and tradition, Brains and Brawn. I wish you the very best as you adapt to that future, and as you continue your journey as a Systems Leader.