Promise, Chaos, and Controls

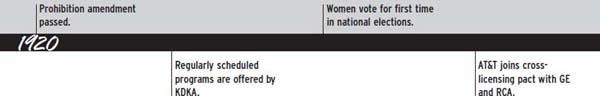

In 1920 radio finally came of age. On November 2 station 8XK (a special Conrad land station), later KDKA, in Pittsburgh broadcast the election returns of the Harding–Cox presidential race and continued its broadcasting thereafter with regularly scheduled programs. Although KDKA is given credit for being the first station on the air to employ a regular schedule of programs, “Doc” Herrold’s San Jose, California, station, ultimately called KQW, which started broadcasting in 1909, did provide a schedule in 1912 to amateurs who had built sets to listen, and music was being broadcast regularly from station 2ZK in New York in 1916. In Detroit William E. Scripps, publisher of the Detroit News, was conducting experimental broadcasting over station 8MK from his office months before KDKA started. At the University of Wisconsin, Professor Earle M. Terry, who had experimented with voice broadcasts using vacuum tubes during World War I, was by 1920 broadcasting weather forecasts every day. Although some historians credit the University of Wisconsin station, 9XM, which became WHA, with being the first station on the air, it was Terry himself who gave the credit to KDKA.

With so many stations doing earlier some of the things KDKA did in 1920, why is the Pittsburgh station now considered the first regularly scheduled broadcast facility? In part, because it was the first one to reach the general public with continuing programming. The other stations reached mostly amateurs on an experimental basis. Before KDKA made its debut, it promoted the purchase of radio receivers among the public, and to be sure that at least some members of the public at large would hear its broadcast, the station’s owner, the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company of Pittsburgh, bought receivers for some employees, executives, and their friends. In addition, Westinghouse arranged for two of Pittsburgh’s leading newspapers, the Post and the Sun, to carry its program schedule. Although as few as 100 persons may have heard the first broadcast, they were members of the general public as well as amateur experimenters, and were scattered throughout Pennsylvania and even in the states of Ohio and West Virginia.

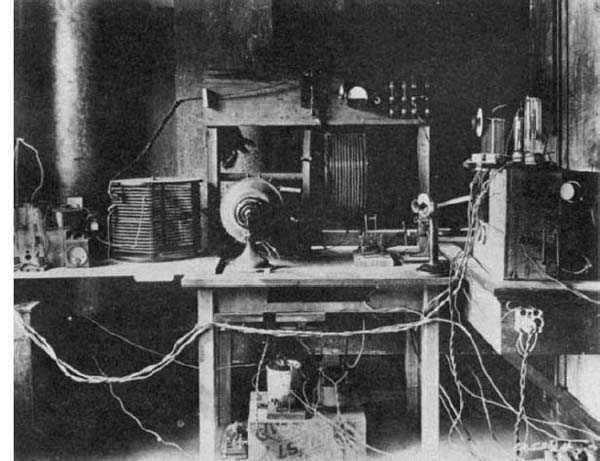

KDKA and the birth of broadcasting are synonymous with the name of Dr. Frank Conrad, Westinghouse’s assistant chief engineer, who for some years had been operating an experimental station, 8XK, out of his garage. During World War I his station tested military equipment built by Westing-house. After the war he even began to inform other amateurs—his listeners—of broadcasts in advance. Conrad’s work and the competition of the then media giants for control of radio resulted in the founding of KDKA.

Site of many of Dr. Conrad’s early experiments that led to KDKA.

Courtesy Westinghouse.

Westinghouse’s vice president, Harry P. Davis, had earlier that year established an agreement with the International Radio and Telegraph Company to try to compete with AT&T and the newly formed RCA, and continued to buy as many patents as possible from Fessenden and Armstrong, including the latter’s superheterodyne circuit, which greatly improved amplification.

To overpower other competitors and avoid a debilitating fight between themselves, AT&T and RCA joined forces and, with GE, signed a cross-licensing agreement for the patents they controlled. When a department store advertised “amateur wireless sets” for $10 in the Pittsburgh Press, citing Conrad’s home-station broadcasts as an inducement, Westinghouse’s Davis saw the opportunity for Westinghouse to enter broadcasting, enhance its image vis-à-vis its competition, and promote the marketing of the receivers it built. It had Conrad construct a more powerful transmitter than that of 8XK, which actually went on the air at the company’s East Pittsburgh plant with test programs a week before its broadcast of the election results.

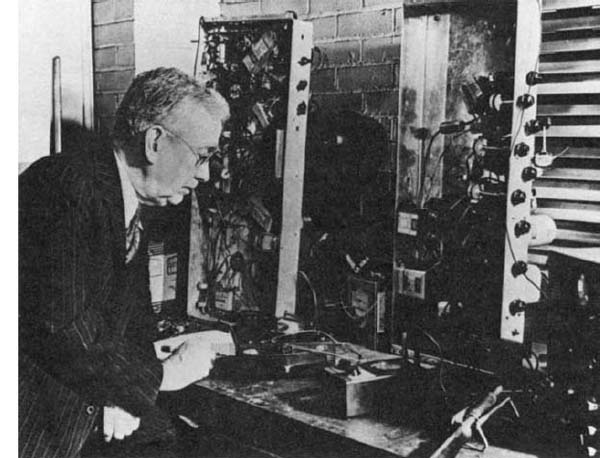

Conrad at the workbench of his station, KDKA.

Courtesy Westinghouse.

Because the experience at KDKA was duplicated to a greater or lesser degree by so many of the stations that followed it, it is worth noting several other aspects of KDKA’s beginnings. Conrad, as announcer as well as operator of the station, began what other stations did later in attempting to determine whether anyone was actually listening to the programs. He asked, “Will any of you who are listening in please phone or write me at East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, telling me how the program is coming in. Thank you, Frank Conrad, station 8XK, signing off.”

The new station played mostly music, principally that of live bands, whose members performed on the roof of the building because the acoustics were better. In bad weather, a tent was used. Finally, with the use of burlap and other materials to reduce reverberation, inside rooms were converted to studios. At some stations studios were very plain—literally broom closets; others soon became very ornate, resembling the music rooms of Victorian mansions. The number of each day’s regularly scheduled broadcast hours grew monthly.

The post–World War I growth and power of the United States were reflected in and stimulated by radio. The prosperity and brashness of the Roaring Twenties, including the increasing domination of big business, gave importance to radio’s live, national advertising potential. War had unified much of America in its own image and greatness and at the same time had introduced it to new ideas and attitudes from abroad. America as a whole emphasized the former, its own image, and rejected the latter, foreign ideas. Except for the increasing American role in, if not domination of, world trade, America isolated itself from much of the rest of the world and reveled in its own internal growth. The government’s immediate postwar national xenophobia concerning “Bolsheviks”; the refusal to join the League of Nations; the national union-busting efforts, including police support of strikebreakers and “goons” and the framing and execution for murder of two radical labor activists, Sacco and Venzetti, in Massachusetts; government efforts to stop the gangsterism that resulted from its Prohibition laws, even while many Americans romanticized the bootleggers; the public’s blind eye to and even support of anti–civil rights and anti–civil liberties actions against ethnic and racial as well as political minorities; the first official entry of women as a group into the political process through electoral suffrage; the growing rivalry between urban and rural America, including the fear of big-city cultural domination; new American-born arts and culture, including the Jazz Age and the Harlem Renaissance; the solidification of the place of professional athletics in our culture; immigrants seeking the peace of isolation and streets paved with gold; people starving, but more people than ever before drinking champagne—all of this and more, the good and the bad, the joyful and the tragic, was the America of the Roaring Twenties. By and large, it was a time of affluence and material possessions, the growth of a new economic middle class, new opportunities through mass production for unskilled and skilled workers, and a national devil-may-care euphoria. Radio fit perfectly into this heady postwar world, sometimes informing, sometimes educating, sometimes assuaging, and mostly entertaining, keeping people’s minds on the happy days and off the troubles. Within a few years radio moved from a hobby to entertainment to a merchandising business.

Early apparatus of two radio studios.

Courtesy Westinghouse and WTIC, Hartford, Connecticut.

KDKA control room in 1920. The station’s staff work the equipment for the Harding–Cox broadcast.

Courtesy Westinghouse.

1921

The first broadcast license granted by the Department of Commerce went to a Westinghouse station—but not KDKA. It went to WBZ, in Springfield, Massachusetts, on September 15, 1921. It wasn’t until November 7 that KDKA officially got its license, the eighth one issued. Of the first nine stations licensed, four were owned by Westinghouse (KDKA; WBZ; WJZ, Newark, New Jersey; and KYW, Chicago) and only one each by RCA (WDY, Roselle Park, New Jersey) and the De Forest Radio Telephone and Telegraph Company (WJX, the Bronx, New York). By the end of the year more than 200 radio stations had been licensed.

Even though not the first licensed, KDKA lived up to its initial reputation by producing other kinds of “firsts.” It carried the first remote church service broadcast, the first regular reporting of baseball scores, the first address by a national figure—Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, on January 15—the first broadcast by a congressional representative (Representative Alice Robertson, long before women were afforded such recognition), and the first time signals.

Less-than-extravagant accommodations: KDKA’s rooftop studio shortly after the station’s debut.

Courtesy Westinghouse.

The broadcasting of sports events provided the greatest impetus for the purchase of radio sets—not unlike the phenomenon today that sees major sports events garnering the highest television ratings. This development was materially aided by the greater signal distance generated by the new 500-watt transmitter, which began to replace the 100-watt transmitter at key stations. The first broadcast of a championship fight, between heavyweights Jack Dempsey of the United States and Georges Carpentier of France, prompted the purchase of thousands of radios, as did the first broadcast of baseball’s World Series, between the New York Yankees and the New York Giants, later in the year. It was estimated that perhaps 500,000 people heard each of these sporting events—an amazing figure, considering the number of sets in operation during only this second year of formal broadcasting. Thousands of people who couldn’t care less about sports were converted to radio by a different event—being able to listen to the live broadcast of President Warren G. Harding’s Armistice Day (now Veterans Day) address from the Arlington Cemetery Memorial.

Although RCA dominated the international wireless market, it continued to have stiff competition from Westinghouse for the domestic market. RCA’s chairman, Owen D. Young, proposed that Westinghouse join its cross-licensing cartel. Westinghouse, seeing this as a possible opportunity to make headway in the international arena, accepted. Young also included the United Fruit Company, which, oddly enough, had significant patents on crystal detectors and loop antennas. Before the year was up, the RCA alliance controlled more than 2000 key radio patents. David Sarnoff, who, as noted earlier, would become the key figure and power in the development of American broadcasting, had become RCA’s general manager. Young was impressed with Sarnoff’s grasp of the medium’s technical potentials (it was Sarnoff who convinced Young of the value of using short-wave rather than long-wave transmissions for better signal distance and quality) and its long-range economic potentials (Sarnoff stressed radio’s value as a lucrative merchandising device at the same time it served the entertainment and informational needs of the public).

KDKA’s first performance studio.

Courtesy Westinghouse.

The race was on to sell radio receivers and broadcasting components. In fact, many of the early stations were owned by the manufacturers of such equipment, using the station’s programming to motivate people to buy sets, which purchases would in turn stimulate the construction of more stations. They also promoted their own products, frequently attaching the name of the product to whatever entertainment group they hired to perform on the station. Westinghouse itself produced a state-of-the-art set for $60—affordable for middle- and upper-income families, but still very expensive for working people, whose pay was about a dollar a day. But other sets could still be purchased for about $10. One way Westinghouse promoted its sets was to establish stations in cities where it had manufacturing plants.

The first factory-built radio receiver enters the home in 1921.

Courtesy Westinghouse.

Not only were manufacturers who produced electronic equipment used in the construction of stations and receivers eager to sell their new products, but department stores set up stations in their stores to draw customers, and hotels did the same thing. The sound from phonograph records did not reproduce well over the air, and almost all music was live. Besides, the listening audiences didn’t want to hear records; they had phonographs at home. They looked forward to hearing live, at home, some of the performers they previously could hear only by paying to go to nightclubs or vaudeville theaters.

All over the country, ads appeared for large companies and small companies that made radio equipment, such as the Crosley condenser and a variety of RCA products. Catalog companies, such as Montgomery Ward, heavily promoted the sale of radios and radio equipment. Even so, many people still constructed their own sets. The novelty of the new medium and the strong selling campaigns produced one of the heaviest demands for a new product in the country’s history.

Radio sold not only equipment but education as well. The glamour of radio resulted in radio training schools springing up in various cities. The National Radio Institute of Washington, DC, for example, ran full-page ads headlined “Do Amateurs Realize the Wireless Opportunities That Await Them?” The ads touted the potential for fame and fortune in the new field. Those who filled in and mailed a coupon received a “free book, Wireless, the Opportunity of Today.”

Even as early as 1921 a new kind of entertainment talent began to emerge. Because the audiences were still relatively small, because the geographic coverage of a given station was limited, and because there was virtually no money to pay performers, well-known stars of vaudeville, nightclubs, the stage, and movies could not be drawn into radio. The first talents to become known—aside from a few new acts that worked cheap—were therefore the announcers, and even they tried to remain largely anonymous. Outside of managers and engineers who at first announced their station’s programs in the manner of Frank Conrad at KDKA, one of the first full-time announcers was KDKA’s Harold W. Arlin, who was responsible for a number of firsts (such as announcing the first play-by-play sports broadcast). At WJZ in Newark, New Jersey, Thomas H. Cowan created a new designation for the announcer by establishing the practice of using initials rather than his name—“This is ACN” (for “This is Announcer Cowan, Newark”); this became the procedure at almost all stations for many years. New York area stations became the breaking-in ground in the early 1920s for the most famous announcers, including such persons as Graham McNamee and Milton Cross, who remained for decades.

In 1921 Philo T. Farnsworth, at the age of 15, was already experimenting with visual transmission concepts that would result in his becoming the “father of American television.”

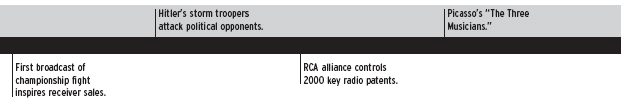

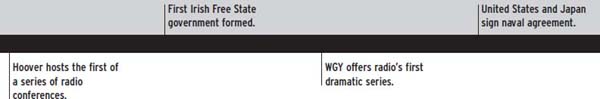

1922

The operational basis for American broadcasting as it exists today was established in 1922 by one event: the first commercial. On August 28 a new AT&T station in New York City, WEAF, which became the NBC flagship station, carried a paid, 10-minute talk by an executive of the Queensboro Corporation extolling the virtues of buying an apartment in a new suburban development called Hawthorne Court—today a highly urbanized area. The station charged $50 for, as it was then called, the “toll-cast” presentation. Four more afternoon presentations were given, and one was made in the evening for $100. These first paid commercials resulted in the sale of apartments, and advertising as the support base for American broadcasting was born. But it took time. Although WEAF received two more accounts—from Tidewater Oil and American Express—income was still insufficient to equal station expenses. What AT&T promoted at the beginning of 1922 as “commercial telephony” didn’t begin to make real inroads until a year later. In fact, at a radio conference in Washington, DC, called by Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, the idea of advertising was discussed negatively, with Hoover stating that he felt “it is inconceivable that we should allow so great a possibility for service to be drowned in advertising chatter.” Nevertheless, in 1923, after 14% of the stations operating in 1922 had gone off the air because of a lack of funds and the remaining stations were desperate to find some way of meeting costs, advertising was again looked at as the financial solution.

Commercial radio was launched at WEAF with this lengthy “toll-cast” designed to sell homes.

A principal problem was that the owners of the more than 200 stations at the beginning of 1922 were supporting them for the purpose of either selling their own products (by the end of the year 40% of the stations were operated by manufacturers or sellers of radio receivers) or promoting their own services (such as churches, newspapers, and hotels). At the beginning of the year only a handful of stations were owned by newspapers; at the end of the year the number was 69. College stations at first didn’t seem to worry about finances for survival, inasmuch as they were, as they are today, educational tools of their institutions, and were supported as such. The first college station to be licensed, in 1922, was Emmanuel College in Michigan; by the end of the year, 74 colleges and universities had stations on the air.

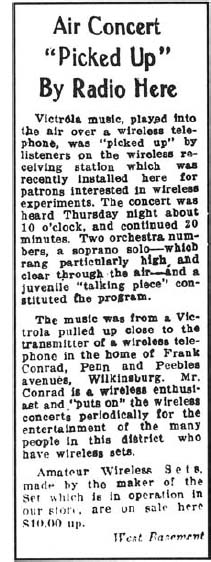

In the early days, radio broadcasts were news stories. Note the revealing information in this newspaper item.

Courtesy Westinghouse.

People were buying radio receivers as fast as they could afford to and as quickly as the receivers were available for this new phenomenon. A lot of money for that time—$60 million—was spent for sets in 1922. The desire for receivers was so great that the demand by retail franchises outstripped the supply of sets. Drugstores, flower shops, clothing establishments, shoe stores, grocery stores, and even blacksmiths and undertakers sought radio-receiver franchises. About 200 distributors served some 15,000 retail outlets. As the agent for GE and Westinghouse products, RCA was at first the dominant force in the market with its receivers and loudspeakers, which acquired the names Radiola and Radiotron, and it tried to force distributors to carry its entire line of equipment. But as the number of manufacturers and the competition grew, each producer began to promote its own brand name and the performance qualities of its product; after a year or so, the public had a choice of many sets at competitive prices. People who couldn’t afford brandname receivers made their own crystal sets from kits—similar to the more sophisticated kits sold today by Radio Shack—or bought factory-made crystal sets for as little as $10 (that was equivalent to 2 weeks’ wages for many blue-collar workers).

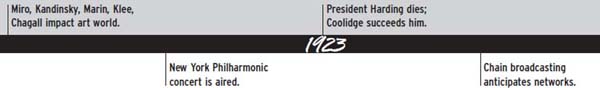

Programming innovations spurred listener interest: a concert by the New York Philharmonic, President Calvin Coolidge’s address to Congress, a “School of the Air” series, the first church services. The Secretary of Commerce prohibited a number of higher powered, major stations from playing recorded music, and the need for live talent grew. Stage celebrities began to appear on radio, notably through broadcasts of Broadway shows, such as The Perfect Fool with Ed Wynn and Ziegfield Follies of 1922 with Will Rogers. Bertha Brainard, who became known as the “first lady of radio,” began regular programs of theater reviews and information in 1922, and the “King of Jazz,” Paul Whiteman, made his radio debut that year. The first dramatic series went on the air on GE’s Schenectady station, WGY, and the first sound effects were used in The Wolf, a two-and-a-half-hour play on the same station.

While the introduction of name talent boosted radio, it also created a problem. Most talent worked for free, seeking the publicity and exposure of the medium. Performers soon began to feel exploited, however, and frequently simply didn’t show up for programs. In fact, some of the performing unions were so concerned about the lack of specified pay that they advised their members not to appear on radio shows.

Remote broadcasts added another new dimension. The first remote pickup of a football game, between Princeton and the University of Chicago from Stagg Field, Chicago, by AT&T station WEAF in New York, further advanced sales of receivers. Attempts to monopolize programming were as strong as attempts to control the technical aspects of radio. AT&T turned down non-AT&T stations’ requests for use of AT&T long lines for remotes, and its competitors were forced to rely on the lower quality Western Union lines, which were not designed for voice transmission.

Technical innovations, especially the demonstration in 1922 of the superheterodyne receiver by Edward Armstrong, emphasized the increasing reach of radio. The first transatlantic broadcast took place on October 1 from London to WOR in New York. That same month saw a demonstration of highpower vacuum-tube transmission among New York, England, and Germany. Westinghouse’s vice president, H. P. Davis, stated that there were no limitations to the potentials of interconnection, that “relays will permit one station to pass its message on to another, and we may easily expect to hear in an outlying farm in Maine some great artists singing into a microphone many thousands of miles away. A receiving set in every home, in every hotel room, in every schoolroom, in every hospital room … it is not so much a question of possibility, it is rather a question of how soon.”

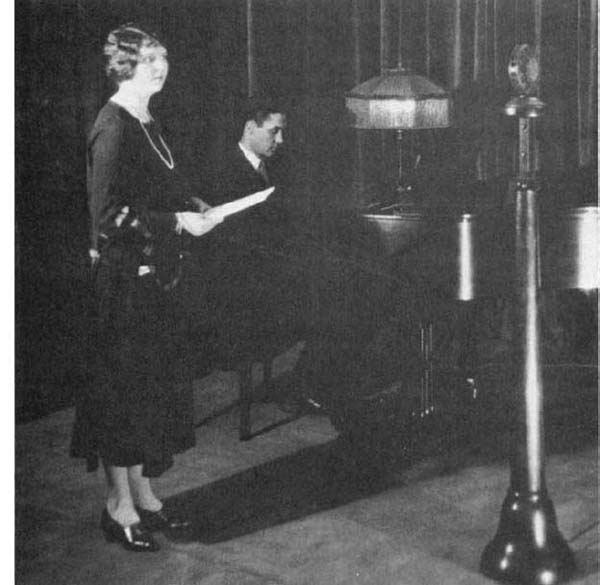

Vocal recitals, with piano accompaniment, were standard fare in the 1920s.

Courtesy WTIC.

As radio grew, it found itself hindered by technical problems and the lack of government regulatory authority. For example, all radio stations broadcast on a frequency of 360 meters, except for government announcements and weather stations, which used 485 meters. With virtually all stations on the same frequency, interference was inevitable, and for a while radio tried to solve the problem by sharing days of the week and hours of the day. Although a new frequency of 400 meters was established for radio, only the more powerful stations—in wattage and finances, and with live programming—got this less congested frequency. In fact, in 1922 a number of stations started a voluntary “Silent Night” that lasted several years: On a designated evening, all local stations went off the air to allow the public to hear some of the higher powered, distant stations, such as KDKA, which had star programming.

Frequency problems and unchecked licensing whereby anyone who wanted to could get authorization to put a station on the air prompted Secretary of Commerce Hoover to call the National Radio Conference mentioned earlier. The leading radio manufacturers and station owners, such as RCA, AT&T, Westinghouse, and GE, were invited to attend, along with representatives of federal agencies and some key individuals from the technical and financial sides of the field. The conference’s recommendation that the Secretary of Commerce be given authority to establish requirements for licensing, frequencies, and hours of operation was turned down by Congress. Some historians suggest that the reason was political, that certain members of Congress did not want to put such power into the hands of Hoover, who was considered a possible Republican candidate for president in 1924. (Hoover ran and was elected in 1928.)

The government was, however, forced to do something about station call letters. As the number of stations increased, the government began to run out of the three-letter call signs that had initially been assigned, so four-letter combinations began to be used. Many stations sought combinations that reflected the owner’s name or initials or that promoted their programming or area. For example, of stations currently on the air in the 1990s, WIOD (Miami) stands for “Wonderful Isle of Dreams,” WTOP (Washington, DC) indicates “Top of the Dial,” WNYC (New York) is the New York City municipal station, and WGCD (Chester, South Carolina) means “Wonderful Guernsey Center of Dixie.” A few years later, in 1927, international agreements divided up call-letter prefixes geographically.

As it was to continue to do, radio prompted the growth of associated media industries as early as 1922. Key radio publications containing mainly feature stories and schedules were founded that year: Radio World, Radio Dealer, and Radio Broadcast, which later became the present-day Broadcasting. At the same time, not every citizen was enamored of the new medium. Like most new inventions, radio created fears, some reasonable and some unreasonable. One long-told story is that of the farmer who complained to the management of station WHAS in Louisville, Kentucky, that a flock of blackbirds was flying over his farm and one suddenly dropped out of the sky, dead. “Your radio wave must have struck it,” the farmer insisted. “Suppose that radio wave had struck me?”

A noteworthy 1922 event reflected America’s sociopolitical attitudes. According to the researcher Estelle Edmonston, this was the year that African American involvement in the medium began. Edmonston states that Aubry Niles, Flouroy Miller, Noble Sissle and his orchestra, Juan Hernandez, Fran Silvera, and comedian Bert Williams were put on the air by N. T. Grantlund at WHN in New York. It would be many years, however, before African Americans would be given the opportunity to perform in broadcasting on a regular basis.

As the euphoria of the audio medium grew, so did the prospect of a visual medium. On June 11 the New York Times carried a photo of Pope Pius XI that had been transmitted, as the Times stated, through “a miracle of modern science.” It was the first transatlantic radio photo.

1923

The success of remotes the year before naturally suggested the potential for interconnection, and the first “network”—or, as it was called then and is still called by many broadcasters and in many legal documents, “chain”—broadcast took place on January 4, 1923. WEAF sent a 5-minute saxophone presentation over telephone wires to Boston’s WNAC, broadcast simultaneously by both stations. (In October 1922, WJZ in Newark and WGY in Schenectady had simultaneously broadcast the World Series—but they were joined not by voice but by telegraph wire.) Throughout the year a number of stations interconnected for carriage of each other’s programs, including the first permanent hookup, on July 1, between WEAF and WMAF (South Dartmouth, Massachusetts), for the latter station’s carriage of WEAF programs. Interconnection experiments culminated in what many media historians consider the first true network, the connection by wire on December 6 of WEAF (New York), WJAR (Providence, Rhode Island), and WCAP (Washington, DC). Continued advances in the use of both wireless and wire for programming ranged from shortwave programs from the United States to England and from Los Angeles to Honolulu to short-range wire transmission of live entertainment from Gimbel’s department store to WEAF in New York.

New programming and new personalities made their mark. The first play especially written and produced for radio was broadcast by WLW, Cincinnati. Variety programs made media stars out of such vaudeville performers as Billy Jones and Ernie Hare, who set a standard for and opened the microphones to many similar comedy acts that would soon follow. Through his voice quality and verbal descriptions, Graham McNamee re-created the excitement and atmosphere of sports events so effectively that he would be the medium’s premiere sports announcer for decades to come. As well, H. V. Kaltenborn began the news commentaries that would make him famous into the age of television. But even in 1923, as today, music was the dominant programming on radio—only then it was mostly live, emanating from hotel ballrooms and specially built studios that were furnished to look like ballrooms or elegant music rooms, resulting in the phrase “potted palm music.” There was, of course, classical music, too; in fact, the first sponsored program was one of classical music, the “Eveready Hour,” in 1923.

News had not yet made its mark. There were no radio news services. Some stations read or paraphrased the stories from their towns’ daily newspapers. A few enterprising stations sent out staff to gather local stories. Some newspapers provided stations in their communities with news summaries to be read over the air. But mostly, news was largely ignored. The principal news broadcasts were Department of Agriculture and Weather Bureau reports to farm areas. A dramatic combination of radio news and public service was demonstrated in 1923 when radio helped locate the kidnapped son of the radio-TV inventor Ernst Alexanderson.

Radio quickly caught the imagination of the public, as in this 1923 photo of a home crystal receiver and its young fans.

Courtesy Westinghouse.

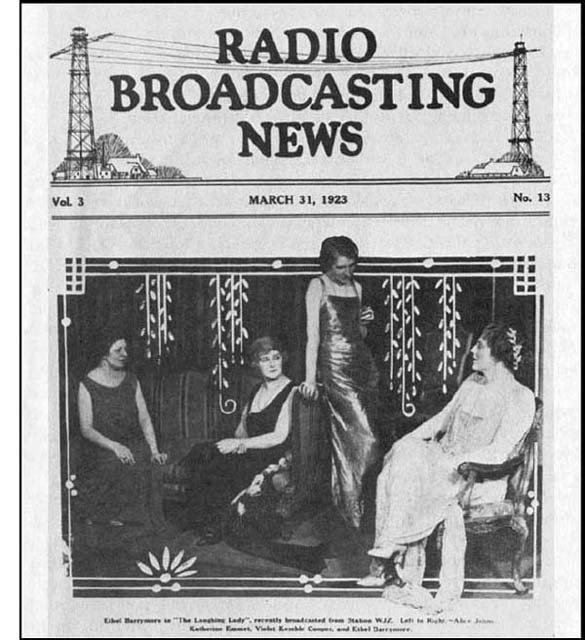

Some stars (Ethel Barrymore at right in photo) were answering the call to the airwaves.

Courtesy Westinghouse.

Programming progressed, but it was not all positive. As a portent of charlatan hucksters and televangelists of a later day, a Dr. John R. Brinkley started station KFKB in Milford, Kansas. The license was finally revoked some years later because of Brinkley’s sales promotion of his own patent medicines and other dangerous or false drugs and even a “goat gland operation” for male sex rejuvenation.

Some of the most dramatic advances in programming came in the field of politics. The right-wing backlash following World War I had made the United States isolationist, the country even refusing to join the League of Nations, while much of the rest of the world was seeking continuing peace through international cooperation. On June 23 President Warren G. Harding made a speech about the World Court that was heard by an estimated 1-million-plus people—a remarkable number for that period and, according to some historians, the true beginning of a politician simultaneously reaching and influencing a huge segment of the public. Plans for a coast-to-coast hookup to follow up the success of Harding’s speech were shelved because of Harding’s death shortly afterward. Although radio carried the inauguration of the new president, Calvin Coolidge, coast-to-coast on a 21-station hookup, Coolidge refused to use the radio medium. No wonder. He spoke in flat, nasal, boring tones. But at the opening of Congress on December 23 (a first for radio), he allowed his speech to be carried by a seven-station network linked by AT&T from New York to Dallas. This resulted in another first: broadcasting making a politician look or sound more appealing than he or she really is. The microphone was placed close to Coolidge and emphasized the lower tones, giving his voice a power and resonance that it ordinarily didn’t have. This gave him a new image of strength that, in the opinion of many, bolstered support for his isolationist views and for America’s political detachment from many developments in Europe, including, later on, the rise of Nazism.

Aeriola Senior radio receiver.

Courtesy RCA.

Former President Woodrow Wilson, increasingly ill and near death, was persuaded to make a speech on radio supporting America’s participation in the League of Nations. For the preceding few years, since the end of his presidency in 1921, he had been largely ignored and virtually forgotten. But the day after his speech, some 20,000 people crowded the streets in front of his home in Washington, DC, urging him to come out to talk to them and be cheered. The Coolidge and Wilson events were among the first examples of the power of the media to affect and even control politics.

As programming and technical proficiency grew, so did the problems that come from unregulated competition. Both RCA and AT&T believed that their patents had been infringed on. RCA was concerned that the thousands of entrepreneurs who were making radio sets with RCA tubes were illegally using processes that it controlled. AT&T claimed that any station using a transmitter not manufactured by its Western Electric subsidiary was violating its patent rights. AT&T offered the 600 or so stations it believed were in violation the option of (1) continuing to broadcast on their “illegal” transmitters in exchange for annual licensing fees or (2) going off the air. The conflict reached Congress, which asked the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to investigate—the first serious investigation by the government of alleged monopoly practices in the media industry, something that would occur frequently in subsequent years, especially following the establishment of the Federal Radio Commission in 1927 and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 1934.

Creative artists complained that radio stations were using their works without permission, usually without compensation. Most concerned was the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP). The previous year, ASCAP had demanded royalties from radio stations that used the copyrighted music of its members. The stations countered that they were popularizing the music, resulting in increased sales of records and sheet music. In 1923 ASCAP negotiated an annual license fee of $500 with WEAF and, using this agreement as a base, sought similar agreements from other stations. When ASCAP won a court case upholding its legal rights, additional stations agreed to a fee (usually about $250 a year), but others simply stopped using ASCAP music. The music, however, was essential, and a number of stations met in Chicago and formed the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) to fight ASCAP and try to work out a plan for free use of the music in exchange for promoting it. Ultimately, NAB and ASCAP negotiated an annual “statutory” fee for unlimited use of the music. NAB eventually became the broadcasters’ principal trade association and lobbying organization in Washington, DC, and today, seven decades later, the same two organizations meet every few years to negotiate a new music-use contract.

These and other problems, especially the increasingly crowded airwaves, prompted Secretary Hoover to call a second National Radio Conference. As a result of this conference, stations were divided into three groups. First were high-powered stations of 500 to 1000 watts and between 300 and 545 meters on the radio dial. These stations were to serve wide areas with no interference; prohibited from using phonograph records, they were required to present live music. Second were stations with a maximum of 500 watts, operating between 222 and 300 meters—stations intended to serve a smaller area without interference. Third were low-powered stations, all on 360 meters and all required to share time to avoid interference; many of these stations, therefore, operated only during the day to avoid the interference caused by the sky wave reflection of the amplitude modulation (AM) signal over long distances after dusk.

The conference also discussed the need for an equitable distribution of frequencies and stations across the country. Further, it recommended that Congress pass a bill establishing a federal regulatory agency to facilitate the growth of radio; however, two more National Radio Conferences would be necessary before that would happen.

Once again, in 1923, as radio grew, so did the genesis of television. Facsimile, or wirephoto, experiments continued, and in Britain, John Logie Baird developed a mechanical scanning system by which he transmitted by wire a silhouette television picture about the same time that Charles Francis Jenkins, an American using a mechanical system he developed at AT&T, transmitted by wireless a picture of President Harding from Washington to Philadelphia. Significant in terms of the future of the visual medium, Vladimir Zworykin, continuing his experiments at Westinghouse, demonstrated the beginnings of a partly electronic television system.

This balloon was used as an airborne antenna (and billboard) in the 1920s.

Courtesy Westinghouse.

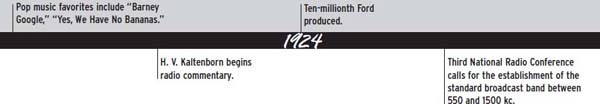

1924

The third National Radio Conference, in 1924, continued to try to solve the problem of chaos on the air. The major result was the expansion of frequencies allocated for radio broadcasting to 550–1500 kilocycles (kc), with power up to 5000 watts. Still, the interference continued and another conference was scheduled for 1925.

There were troubles on the business front for broadcasting, as well. The FTC completed the report of its monopoly investigation begun the previous year and issued complaints against RCA and seven other companies, known as the “patent allies,” for their alleged stifling of free competitive growth of the medium.

Some government officials were taking a more favorable attitude toward radio, however, Calvin Coolidge, who had looked askance at radio when he succeeded Harding as president following the latter’s death in 1923, was now running for the presidency on his own. He used a 26-station, coast-to-coast hookup to make a campaign speech. Other politicians jumped on the radio bandwagon, too, following radio’s coverage of both the Republican and the Democratic National Conventions of 1924, coverage that stimulated heavy increases in the purchase of radio sets.

President Coolidge and Secretary Hoover address a gathering of broadcasters at the White House for the third National Radio Conference, December 1924.

Radio was growing, all right, and public support was increasing, but many stations were wondering how and where they would get the funding to stay on the air. The few attempts at advertising had not taken off as hoped, and there was no widespread commitment to use commercials as the financial base for the medium. What were the alternatives?

Secretary of Commerce Hoover wanted the radio manufacturing and sales industry to support the stations. In fact, at the third National Radio Conference he said, “I believe that the quickest way to kill broadcasting would be to use it for direct advertising. The reader of the newspaper has an option whether he will read an ad or not, but if a speech by the President is to be used as the meat in a sandwich of two patent medicine advertisements there will be no radio left.” David Sarnoff of RCA said radio should be financed through grants and endowments, as museums and libraries are. A GE official, Martin P. Rice, advocated what was later to become the dominant system of support in many countries throughout the world, the licensing of individual sets; he also suggested voluntary contributions from listeners. But none of these was about to work in the United States because the costs of personnel and equipment were much higher than any of these revenue alternatives—other than license fees for sets—were likely to offset. Within a year it had become clear that advertising was probably the only viable financing method.

A broadcast production at Chicago station KYW.

Courtesy Westinghouse.

Still, stations were stymied. AT&T’s earlier agreements with stations giving them permission to use its transmitters included exclusive rights for AT&T to any advertising (or “toll broadcasting,” as it was then called) on those stations. AT&T charged an additional fee when any station carried paid advertising, thus reducing the income the station earned from that advertising. The so-called Radio Group, headed by RCA, and the Telephone Group, headed by AT&T, were locked in a struggle over this issue, and over several others. The following year, in 1925, the two groups agreed to binding arbitration to solve the dispute. The arbitrator found in favor of the Radio Group. Now both groups had to find a common ground if radio were not to split apart entirely. Until they could agree—this occurred the following year, 1926—advertising was not permitted. Even then, the kind of advertising that was done was what today is called institutional—the goodwill promotion of a company or of a product or a service, but without specific details or “hard sell” information on actual purchasing. It would be a few years more before the modern concept of commercials took full hold.

The number of listeners and potential customers grew. When Westing-house brought Armstrong’s superheterodyne receiver into the patents pool, RCA was able to produce a set with highly improved reception. It was, as one might expect, fairly expensive. An RCA competitor, Crosley, countered with a small $10 set; its one tube, however, could receive a signal of only up to 15 miles distance. The approximately half-million sets in use in 1923 grew to more than one-and-a-quarter million in 1924, with the public spending about $139 million for new receivers that year.

Even though broadcasting was still in its childhood, its remarkable growth in just a few years prompted the people’s representatives in Congress to be concerned about possible future monopolization by private interests at the expense of the public interest. In fact, in 1924 Congress passed a bill that presaged the Radio Act of 1927 and the Communications Act of 1934, in which it asserted the government’s authority to regulate radio and clearly stated that the “aether,” or airwaves, belonged to the people.

“The aether belongs to the people.…” Popular microphones of the 1920s.

Courtesy Steele Collection.

1925

A fourth National Radio Conference tried again to solve radio’s problems of overcrowded airwaves and interference. Although many recommendations were made, including extended license periods for stations, wartime radio powers for the president, and safeguards against censorship, the one concrete result was a freeze placed on the issuing of new licenses. The purpose of the freeze was to give broadcasters and the government a respite from dealing with increasing growth crises, so as to be able to determine some workable solutions for the future. The Department of Commerce did, however, permit existing stations to be bought and sold. Hence, the practice of owning stations for the purpose not of providing programming in the public interest but of making a quick buck by reselling in a short time—similar to what happened in broadcasting under the deregulation of “trafficking” in the 1980s—began to invade the industry.

Congressman Wallace H. White, Jr., of Maine had introduced bills following previous National Radio Conferences that would give the Secretary of Commerce the power to regulate radio, but none was approved. He did so again after the fourth National Radio Conference in 1925; this bill, after a number of revisions, would be passed 2 years later as the Radio Act of 1927.

College stations continued to grow. More than 150 such stations were authorized by the Department of Commerce, with about 125 actually on the air. But attrition began to set in: 37 went off the air in 1925 alone.

As controversial issues, such as the Scopes trial, were broadcast by stations such as WLS, the public continued to buy sets almost as quickly as they could be manufactured. Some estimates put the sales of receivers in 1925 at as many as 2 million, and by the end of the year one out of every six homes in America had a radio set.

Microphones were often concealed to reduce performers’ anxiety. In this instance the microphone is disguised with a lamp shade.

Courtesy WTIC.

As professional radio grew, so did amateur radio. Many of the people who for years had experimented with the new medium at home continued to do so as a hobby, not making a transition into the new world of stations and the business of broadcasting. They found that the growth of formally programmed stations tended to restrict their use of radio to broadcast to one another. The American Radio Relay League had been established by these amateur, or, as we now call them, “ham,” operators before World War I, and it was now expanding. In 1925 a conference was held with representatives from 23 countries, resulting in the formation of the International Radio Union to fight the regulations that were restricting the growth of amateur operators throughout the world.

Interested spectators look on as New York station WRNY broadcasts.

As music on radio expanded, live and recorded both, the phonograph and the vaudeville industries were beginning to feel the pinch. Many people stopped buying records because they could now hear the music free on radio. Many also saved the admission fees for vaudeville houses by staying at home and hearing variety acts and bands free on their radios, much like what happened to local movie houses when television came into America’s homes. Although vaudeville started a downward slide from which it never recovered, the reverse was true for the record industry. Eventually, the promotion of records on radio resulted in greatly increased sales, and some record companies began to bribe programmers to play their records.

Conductor Walter Damrosch led the New York Symphony over the radio in 1925. This event marked the beginning of a long tradition of live classical music broadcasts.

Courtesy Anthony Slide.

1926

A most significant event in 1926 established the concept and organization of network broadcasting that continues even today. At the urging of David Sarnoff to establish what he called a central broadcasting system, RCA (50% owner) joined with GE (30%) and Westinghouse (20%) to found a new entity, which they called the National Broadcasting Company (NBC). Leasing AT&T lines for hookup, RCA set up an initial network of 19 stations. For a flagship station it bought AT&T’s WEAF in New York for $1 million—a huge sum for those days. Ironically, the selling of WEAF was the beginning of the end of AT&T’s venture in broadcasting, even though it later attempted to set up its own network. That NBC’s bottom line was business, the same bottom line that broadcasting practices today, was reflected in its choice for its first president, Merlin H. Aylesworth. Aylesworth had managed the National Electric Light Association and had business acumen, but allegedly little knowledge of broadcasting; it was said that he didn’t even own a radio set.

NBC started off its new network with a blockbuster—a huge special from the grand ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York, featuring leading orchestras, popular singers, and opera stars of the day, with an invited elite audience of some 1000 persons. It even carried remotes, including one from Kansas City featuring Will Rogers, the country’s outstanding humorist. The program was carried by 25 stations nationally and heard by millions of people. So successful was NBC’s concept that by the end of the year it had two networks: the NBC Red Network, with WEAF as the key station, and the NBC Blue Network, with another New York City station, WJZ, as the flagship.

Newspaper advertisement proclaiming establishment of the nation’s first broadcast network.

A 1926 broadcast of a Brooklyn Dodgers baseball game by Graham McNamee.

Why Red and Blue? Perhaps the most authoritative explanation is that when NBC was drawing the paths of the two planned networks on a map of the United States, it used a red pencil for one and a blue pencil for the other. A later story is that in order to determine which programs originating in the same studio went to which network, one line taped onto the floor was colored red, the other blue. And yet another account has it that the wiring of one set of stations was wrapped in red while the other was covered in blue. NBC had a stronghold on national broadcasting, one it would retain, despite competition from new networks, for more than 15 years until the federal government broke it up.

With the settlement of the AT&T Telephone Group vs. RCA Radio Group fight, the NBC affiliates were able to carry advertising, and NBC began an aggressive campaign to seek sponsors for its shows. Not only did it sell time on its network programs, but it purchased time on its local stations, slots it also sold to advertisers. Within a year the 60-second commercial was established, and it became the economic lifeblood for broadcasters throughout the country.

A British Marconi Company transmitting antenna, beaming wireless signals to the United States in 1926.

A U.S. district court decision in early 1926 provided impetus for Congress to do what the National Radio Conferences of the four previous years and the Secretary of Commerce had unsuccessfully pleaded with it to do: Establish a government radio regulatory body. It did so the following year, as a solution to the district court ruling that the Commerce Department did not have the statutory authority to prevent the Zenith Corporation from putting its station on a frequency other than that assigned by the Secretary of Commerce. In other words, in the Zenith case the court said that the government did not have the authority to prevent any station from using any frequency and power, even if they interfered with other stations. With total chaos on the air now legally possible, Congress seemed to have little choice.

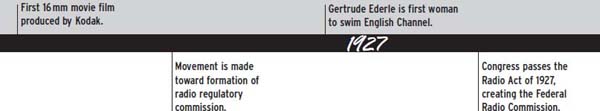

1927

On February 18 Congress passed the Radio Act of 1927, which was signed into law by President Coolidge on February 23. It was also called the Dill–White Act, after its two principal sponsors, Senator Clarence C. Dill and Representative Wallace H. White. The act established the first broadcasting regulatory body in the United States, the Federal Radio Commission (FRC), consisting of five commissioners.

The FRC was given regulatory authority over radio, including the issuance of licenses; the allocation of frequency bands to various classes of stations, including ship and air; the assignment of specific frequencies to individual stations; and the designation of station power. Under the act, it was also given authority to require each station to control its own programming, and to show that it had funding before it could be licensed. The FRC could deny a license to an applicant that had been found guilty of forming a monopoly, and could prohibit control by a telephone company over a radio station or by a radio station over a telephone company. It was given authority to develop regulations for broadcasting, including networks. In addition, the Secretary of Commerce was authorized to inspect radio stations, examine and license radio operators, and assign radio call signs.

The FRC established the AM band as 550–1500kc (later expanded to 1600kc, and in 1990 to 1705kc). There were a total of 96 frequencies, and 40 clear stations were set up in eight geographic zones. Power was raised, up to 25 kilowatts (kW), and later to 50kW for one group of stations, with others in intermediate categories, certifying the actions taken by the Secretary of Commerce following the fourth National Radio Conference.

The distribution of radio frequencies and power allocations as of June 1927.

Two of the more significant aspects of the Radio Act were (1) the requirement that stations operate in the “public interest, convenience, or necessity” (inspired in large part by Hoover’s insistence that radio realize its great potential as an instrument for the public good) and (2) the declaration that all existing licenses were null and void 60 days after approval of the act. Although Congress did not specifically define what it meant by “the public interest,” “convenience,” or “necessity”—and has not done so to this day—the statement established the base for later regulation that went far beyond technical supervision, which was the principal motivation for the Radio Act of 1927. The FRC did use its authority under that provision to take action in regard to certain program content that exploited or deceived the listener, such as religious charlatans intent on milking the public for donations, patent-medicine hucksters, and fortune-tellers.

The voiding of existing licenses forced all stations that wanted to stay on the air to apply for new licenses. Most of them did reapply. But in setting up an orderly system of frequency and power assignments to solve the chaos, the FRC refused to renew the licenses of many stations and forced many others to less desirable frequencies. For the most part, the larger, more powerful, and more influential stations got the best frequencies. College stations, for example, were forced off the air by the dozens, many of them unable to get licenses and many more being assigned the worst frequencies, their former frequencies given to commercial stations. All in all, some 150 of the 732 stations on the air before the act was passed were forced to surrender their licenses.

A radio audience questionnaire in the February 1927 issue of Radio Broadcast magazine.

Felix is TV’s first image.

Courtesy David Sarnoff Library.

Did the Radio Act of 1927 and the establishment of the FRC result in radio operating in the public interest? More than 40 years after passage of the act, one of its sponsors, former Senator Clarence Dill, was not so sure. In answer to a letter inquiring about the original Radio Act, he expressed concern that the FRC’s successor, the FCC, was not protecting the public against commercialization of the airwaves and hoped the people would insist on use of frequencies for the “public interest” rather than for “private profiteers.”

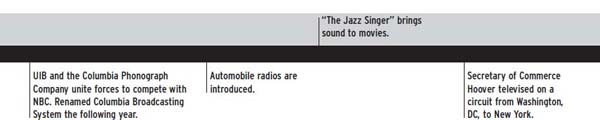

Meanwhile, broadcasters concentrated on what was in their own best interest. NBC’s success prompted others to look at network possibilities. Early in 1927 the United Independent Broadcasters (UIB) association was formed, and although it signed on a number of affiliates it was unable to raise enough money to activate a real challenge to NBC. In fact, its financial condition was so shaky that AT&T wouldn’t let it use AT&T interconnecting lines, in the fear that UIB wouldn’t be able to pay for them. The Columbia Phonograph Company was the chief rival of the Victor Phonograph Company, which was about to merge with RCA, the controller of NBC. Columbia decided to go into head-to-head competition with NBC by joining with UIB to form the Columbia Phonograph Broadcasting System, later to become the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) and NBC’s principal network competition. With three networks in operation, there was no longer a need to clear the airwaves on a given night to receive large, live-performance stations, and the “silent night” practice was abandoned.

Sales of sets increased, as did the variety and impact of programming. RCA licensed several competitors, such as Crosley, Atwater Kent, Philco, and Zenith, to make sets under the so-called “patent-allies” patents in return for substantial royalty payments, thus increasing the availability of receivers. An estimated 15 million sets were in use in the United States, and in 1927 alone about $500 million worth of receivers were purchased. Although battery sets were still in use, especially in rural areas where there was no electricity, radios operating by electric power were increasing. However, one new use of battery-powered radios did arise in 1927: Automobile radios were introduced.

That year, people heard such events as Charles Lindbergh’s return from Paris after making the first solo airplane flight over the Atlantic Ocean to become, arguably, America’s greatest hero of the century. This was the first time an event was covered by a number of announcers representing many stations.

Many companies sponsored programs bearing their names: the “Maxwell House Hour,” the “General Motors Family Party,” the “Eveready Hour,” and the “Sieberling Singers,” among others, all products still advertised today. Live concert music was a favorite and dominated NBC’s schedule. Shows were live and had to be done correctly at air time. There was no way to record and play back programs with any degree of fidelity; besides, the government, the listeners, and the networks all promoted live programming.

The towers of one of the nation’s earliest stations—WOW.

So popular had radio become that newspapers were now beginning to worry seriously about competition. They were not so much concerned about radio news reports—radio had not yet developed its news broadcasts enough to compete seriously with the print press—as they were concerned that some of their advertisers were cutting back on their newspaper advertising and putting that money into radio advertising. In New York, for example, some newspapers that had carried radio program schedules for free now refused to print them unless they were paid to do so by the radio stations. These newspapers, however, began to lose readership to those newspapers that continued to carry radio schedules, and the boycott fizzled. But the competition grew, turned into resentment, and resulted in a press vs. radio war a few years later. The solution for some newspapers was to buy radio stations, and by the end of the year about 13% of the radio stations in the country were owned by newspapers.

Even as the still relatively new medium of radio was flexing its business and artistic muscles and moving from adolescence into maturity and power, an event occurred that would, in another quarter century, totally change the face of broadcasting in the United States.

The year before, in 1926, the English inventor John Logie Baird had given the first public demonstration of television, in London. Now it was America’s turn. On April 7, 1927, in what was headlined in the New York Times the next day as America’s first “test of television,” Secretary of Commerce Hoover was televised on a circuit from Washington, DC, to New York. Although the transmission was primitive by today’s standards—a resolution of only 50 lines—Hoover could be seen and heard. The New York Times headline read “FAR-OFF SPEAKERS SEEN AS WELL AS HEARD HERE IN A TEST OF TELEVISION.” The Times described the event:

Herbert Hoover made a speech in Washington yesterday afternoon. An audience in New York heard him and saw him. More than 200 miles of space intervening between the speaker and his audience was annihilated by the television apparatus developed by the Bell Laboratories of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company and demonstrated publicly for the first time yesterday. The apparatus shot images of Mr. Hoover by wire from Washington to New York at the rate of eighteen a second. These were thrown on a screen as motion pictures, while the loudspeaker reproduced the speech …. It was as if a photograph had suddenly come to life and begun to talk, smile, nod its head and look this way and that …. Next came … the first vaudeville act that ever went on the air as a talking picture …. The commercial future of television, if it has one, is thought to be largely in public entertainment—super-news reels flashed before audiences at the moment of occurrence, together with dramatic and musical acts shot on the ether waves in sound and picture at the instant they are taking place in the studio.

That same year another event took place that moved television even further along, from a mechanical to an electronic system. The American inventor Philo T. Farnsworth—who became known as the “father of American television”—applied for a patent for a dissector tube, which provided the base for electronic operation. He transmitted a television image with a resolution of 60 lines and experimented with a mechanism that could produce 100 lines. Prophetically, the image projected in his 60-line demonstration was a dollar sign ($). In 1990 Farnsworth’s widow, Elma Farnsworth, commented on that 1927, first all-electronic transmission in terms of its influence on today’s television: “He had the six basic patents used in every TV today. You take Farnsworth’s patents out of your TV and you’d have a radio.”

Belief in the prospective growth of the new medium was indicated with the founding of a new magazine dependent on television’s fortunes, Television.

Today we have an excellent opportunity for Monday-morning quarter-backing by looking again at the New York Times story about the April 27 test of television. The Times was responsible, perhaps, for one of the great misprognostications of all time in one of the story’s subheadlines. It said “COMMERCIAL USE IN DOUBT.”

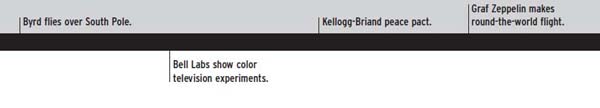

1928

It took a cigar company executive to rescue the Columbia Phonograph Broadcasting System (CPBS) from failure only a year after it was begun and to guarantee a competitive network system for America for at least the rest of the century. The Congress Cigar Company in Philadelphia, owned by William S. Paley’s family, saw its sales zoom after it began advertising on the United–Columbia network. When CPBS began to falter, Paley bought a majority share for $300,000, became first its president and later its chairman, and led the renamed CBS until his retirement in 1983. To this day, only the name William Paley has rivaled that of David Sarnoff in discussions of the leading mogul in the history of U.S. broadcasting.

Will Roger’s radio broadcasts entertained millions during the medium’s early days. Photo by Lee Nadel.

With these two resourceful and ambitious young men guiding the fortunes of the fledgling networks, the broadcast industry made quick advances. Stations increased, sets proliferated, and advertising grew. Broadcasting leapt forward as had the Roaring Twenties of speakeasies (illegal saloons operating during Prohibition), flappers (named after the loose clothing they wore), jazz, dance contests, and increased participation in sports. “Talkies” had invaded the movies; women were beginning to enter male-dominated fields, including aviation—Amelia Earhart made a transatlantic flight just a year after the solo barrier had been broken by Charles Lindbergh. It was a time of avant-garde art, music, literature, sex, and national machismo, from the popularization of artist Salvador Dali, writers Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway, and composer George Gershwin to that of movie idols like Greta Garbo and Rudolph Valentino and hoodlums like Al Capone.

Opposition to proposal that broadcasters honor their public responsibility. This item appeared in the October 1928 issue of Radio Digest.

For those who were white and middle class it was a decade of affluence, joy, daring, and abandon. America spent beyond its means, a “me generation” ensconced in materialism, incurring debts as though the fountain would never run dry. The year 1928 would be the last full year of a carefree America before the stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression that plunged most of the country into gloom and poverty for more than a decade. But in 1928 programming and especially its content still reflected the nonchalant feeling of the country at the time: mostly music, increasing variety shows, some drama, a few feature programs oriented to the housewife, and not much news, education, or children’s programming.

In 1928, 677 broadcasting stations were on the air, and radio sales zoomed to $750 million, with about 8 million radios in use. The economic power of women was increasing, with programs and advertising beginning to reflect this fact. In addition, manufacturers were beginning to style radios as attractive pieces of furniture, promoting them not only as entertainment devices but as interior decor. More and more cars came equipped with radios or had them installed.

Advertising on radio was by now acceptable at most large corporations. The networks could reach some 60% of the population of the United States at a given time, interference was just about gone, and many companies saw sharp increases in sales after they advertised on radio. The manufacturers and distributors of radio sets were the largest advertisers on the medium. Although that’s no longer the case, other leading advertisers in 1928—such as automobile, drug, and toiletries companies—continue to dominate today, on both radio and television.

Advertisers used the advertising agencies that had been handling their print ads to handle their radio ads and supervise the programs they sponsored. The cost of sponsoring a complete program was comparatively lower than it is today. Advertising agencies literally prepared the entire package for a given advertiser. The agencies produced virtually all the sponsored shows on the networks—writing the scripts, hiring the performers, and designating the producers and directors. Because of their control over programs and commercials, ad agencies became the dominant power in radio and, later, in television. Their strength began to diminish in the 1960s, when the costs of production and commercial time for a given program became too burdensome for any one advertiser.

While station owners and their stockholders were pleased with the growth of advertising, many of radio’s pioneers, such as Edwin Armstrong, and political figures who had made it possible for radio to be established and grow, such as Herbert Hoover, lamented the commercialization of a medium they believed should and would be used solely for entertainment, information, and education in the public interest.

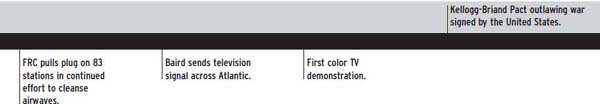

The FRC apparently pleased enough of the industry, the public, and Congress to remain a while longer. The Radio Act of 1927 had established the FRC for just one year. In 1928 Congress renewed its mandate. In 1928 the FRC, following through on the frequency cleansing it had begun the year before, forced 83 stations off the air as it reallocated channels and licenses. The demise of the college-licensed educational stations continued, with 23 more closing their transmitters that year.

Television loomed larger on the horizon. Although the FRC did not encourage the growth of television, and the companies with large investments in radio did their best to keep the new medium from reaching a point where it could compete with their radio stations, experimental advances were made. The FRC granted an experimental license to RCA, and the GE experimental station in Schenectady, New York, began broadcasting on a limited but regular schedule, making history on September 11 with the telecast of the first television drama, “The Queen’s Messenger.” The FRC acknowledged the future by assigning five channels for experimental television stations.

1929

Radio programming and the materialistic abandon of the Prohibition Era would roar together into the last year of the decade, the American middle and upper classes mindless of the consequences. Music filled the airwaves:pop singers, pop instrumentalists, pop bands; serious music, too, from string quartets to symphony orchestras. Variety shows on radio increased, as more and more stage and vaudeville stars began to test the waters of reaching more unseen people in one performance than they had played to in theaters throughout their careers.

Presidential candidates take to the airways in 1928.

“Amos ‘n’ Andy” topped the list of popular network radio shows. The actors were white, but put on “blackface” makeup.

Courtesy Anthony Slide.

Two types of radio drama made their debut: (1) the so-called “thriller” drama, somewhat equivalent to the horror and adventure TV programs of the last decades of the 20th century, and (2) serial drama, that is, continuing characters in a continuing story, a genre that expanded into many forms on radio, and later on TV, from day and evening soap operas to sitcoms to cop–cowboy–clinic series. Their successes perhaps reflecting national attitudes of patronization, condescending tolerance, and insensitivity, the two series that made their network debuts in 1929 and continued for many years as America’s favorites were both about ethnic minorities.

One, “The Rise of the Goldbergs,” was the continuing saga of an urban Jewish family. Although the characters and situations were stereotyped, they were treated gently and often with dignity. “The Rise of the Goldbergs” continued on radio and into television, ending only during the 1950s McCarthy era when the show’s star, Gertrude Berg, protested the network’s blacklisting of the program’s male lead, Philip Loeb, and the program was dropped.

The other program that made its network debut in 1929 was “Amos ‘n’ Andy,” in which two white performers, Charles Correll and Freeman Gosden, portrayed the two black characters of the show’s title. Although Amos and Andy were never shown as evil, they were presented in the racist stereotypes of the time: not very bright, inept schemers, somewhat lazy and shiftless, willing to bend the law if they could get away with it, generally irresponsible, and virtually illiterate. Despite many complaints, this program became the most popular radio show of its time—even a president of the United States allegedly ordered no appointments or meetings when “Amos ‘n’ Andy” was on the air—and perhaps the most popular of all time, with audience loyalty even exceeding that for the TV era’s Milton Berle show and “I Love Lucy.” “Amos ‘n’ Andy” later became a television series with black actors, but increased public concern about its racist implications ended the TV version’s run in the mid-1950s.

Sponsors increasingly lent their names to the program titles. For example, in 1929 we could hear velvet-voiced announcers open programs by saying: “And now, the Philco Hour, with Leopold Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra,” … “the Chase and Sanborn Choral Orchestra,” … “the Firestone Orchestra,” … “the General Motors Family Party,” … “the RKO Hour,” … “the Johnson and Johnson Program, a musical melodrama,” … “the Dutch Masters Minstrels,” … “the A & P Gypsies Orchestra,” … “the Cliquot Eskimos Orchestra,” … “the Old Gold program, with the Paul Whiteman Orchestra,” … “the Wrigley Revue,” … “the Lucky Strike Dance Orchestra,” … “the Smith Brothers—Trade and Mark,” … “the Stromberg Carlson Sextette,” … “the Empire Builders—a thriller drama brought to you by the Great Northern Railroad.” There were some news, public affairs, commentary, and even religious programs, but with few exceptions, they were all sustaining—that is, without paid advertising. Even back then, most of the public wanted the media to entertain, not stimulate, and radio was largely “chewing gum for the ears,” just as much of television later became “chewing gum for the eyes.”

Early network studios.

With programming and advertising now inextricably entwined, how was the advertiser to know which programs to sponsor, which would most likely sell more of his or her product or service? In Cincinnati, Archibald M. Crossley established the Cooperative Analysis of Broadcasting to find out. Using principally morning-after phone surveys, Crossley estimated the percentages of radio homes that listened to specified programs, and he made this information available to networks and stations for a fee. From that beginning, ratings evolved to their present-day dominance over television programs and radio formats. An interesting by-product of Crossley’s work was his finding that people listened to radio most between 7:00 and 11:00 P.M. He called it “prime time.” Seven decades later the same definition and breakdown of hours of prime time still apply.

As commercialization increasingly dominated radio, many listeners and organization and governmental leaders increasingly expressed their concerns. In an effort to preempt the FRC from imposing programming and advertising standards on the industry, the NAB took the self-regulation approach and adopted a Code of Ethics. The code included recommendations that stations avoid broadcasting “fraudulent, deceptive, or indecent programs”; carry commercials only before 6:00 P.M.; and exclude false or harmful advertising. Compliance with the NAB code was voluntary; many of its members subscribed to it, and some adhered to it. With changes over the years dictated by the growth of radio and the development of television, the NAB radio and television ethics codes lasted until they were dropped in the 1980s.

Radio microphones follow President Hoover as he tosses out the first ball of the 1929 season at Griffith Stadium in Washington, DC.

Courtesy Artist’s Proof, Alexandria, Virginia.

On October 29, 1929, one era came to an end and a new one began. On what was known as Black Tuesday, the stock market—the barometer of America’s free-spending, live-for-today, 1920s philosophy—crashed. The stock market had been riding high, and not only the rich but even working people were investing in stocks, assuming that the sky ride would go on forever. Businesses failed, many investors who lost everything committed suicide, and money and jobs dried up. It would get worse. At the end of 1929 more than 60% of the U.S. working population earned less than $2000 a year; a few years later a family of four could live on $14 a week—if they could get that much money. Fully 17% of Americans were out of work. People were literally starving and dying on the streets of urban America and in the backroads of rural America. The free-spending, debt-incurring days had caught up with us and it was time to pay the piper.

While the stock market crash ushered in the Great Depression, with millions of people descending into poverty and hundreds of thousands of businesses going under, radio boomed. Why? Because although tens of millions of Americans now could not afford the 10 cents for a movie show, they could be entertained for free on their home radio. Most of America became a captive radio audience.