Chapter 2

The Emerging Role of the Business

Analyst in Portfolio Management

In This Chapter:

Strategy Execution

Why Portfolio Management?

Defining Portfolio Management

The Portfolio Management Process

Portfolio Management at the Project Level

The Role of the Program Management Office

Implementation Strategies

Challenges

Best Practices

As discussed in Chapter 1, strategic planning is the process of defining the mission and long-range objectives of an organization. It focuses the executive team on the organization’s reason for being and lays the groundwork for the organization to make the most worthwhile investments to bring about desired changes. The scarcity of resources and time-to-market considerations force organizations to choose which improvements and innovations to invest in to align change initiatives with strategies. The challenge is to learn how to invest in those ideas that will bring the most value to the organization, the fastest, with the least risk.

In our global economy, there is a growing need to decrease the time it takes to make an informed decision. In other words, there is a need to improve the organization’s decision velocity. Determining the most valuable candidate projects, however, requires some degree of analysis and planning. These analysis and planning activities occur within the enterprise analysis phase of the business solution life cycle (BSLC), culminating in a decision to invest in the new initiative, defer investment, or reject the proposed initiative altogether.

This chapter first examines why strategy is difficult to execute and why portfolio management is becoming a critical business management practice, and then defines the business analyst’s role in portfolio management activities.

Strategy Execution

After strategic goals, themes, and measures are in place, program and project teams execute plans to achieve strategies. As the executive leadership team becomes more adept at the processes used to select and manage a portfolio of valuable projects, the amount of time they spend monitoring and governing strategic projects increases substantially. Throughout the BSLC, the business analyst and project manager present information to the executive leadership team so they can continually monitor project cost, schedule, risk, and quality for funded strategic initiatives; make course corrections along the way; review proposals for new initiatives developed and presented using sophisticated professional business analysis practices; and measure the value of project outcomes for the enterprise after deployment.

Organizations that execute strategy well do it by making strategy execution a core competency. The most innovative brainchild or creative suggestion does not add value unless turned into valuable products and services. According to Norton, “Ideas are only powerful if you can execute.”1 Norton goes on to propose a five-step process to establish and execute well-formed strategies:

Mobilize change through executive leadership: execute and continually monitor progress toward achieving critical strategies

Translate strategy into operational terms: select and prioritize the most valuable projects through an effective portfolio management process

Align the organization to the strategy: allocate resources to highest priority strategic projects first

Motivate to make strategy everyone’s job: communicate the right message to the right people, align performance measurements to strategies, and reward progress toward strategy execution

Govern to make strategy a continual process: monitor, implement corrective actions, and provide executive oversight for strategic projects.

Well-formed strategies are translated into operational terms through a portfolio of programs and supporting projects. Resources are allocated to the most strategic projects first, aligning the organization to the strategy. Strategic project teams are recognized and rewarded for the value their project outcomes bring to the organization. Ongoing project reviews by the portfolio management group facilitate course corrections and refinements along the way.

So, how well do Fortune 500 companies execute strategy? According to David Norton, less than 10 percent of successfully formulated strategies are effectively executed.2

Eighty-five percent of executives spend less than one hour per month on strategy.

Eighty-five percent of executives spend less than one hour per month on strategy. Ninety-five percent of employees do not understand their organization’s strategy.

Ninety-five percent of employees do not understand their organization’s strategy. Sixty percent of organizations do not link strategies to the budget.

Sixty percent of organizations do not link strategies to the budget. Seventy percent of organizations do not link strategies to incentives.

Seventy percent of organizations do not link strategies to incentives.

We can assume that an equally disturbing percentage of programs and supporting projects are not aligned to strategies.

Why is this the case in corporate America, the most sophisticated business environment in history? Why is it that contemporary corporations and public entities continue to invest heavily in information technology (IT) projects to improve business operations without confirming that their strategy is correct?

According to Norton, businesses don’t take time to confirm their strategies because “they can’t manage something they can’t describe.”3 Norton presents the argument that businesses without confirmed strategies lack an effective framework for describing and executing a business strategy. For example, the chief financial officer (CFO) may have a well-known financial strategy and an established financial information framework, but the chief executive officer (CEO) and executive leadership team may not have a similar framework for describing their business strategy. This discrepancy may impact an overall strategic framework driving business decisions.

As organizations struggle to implement project portfolio management, they are executing their strategy. It is the portfolio management process that links strategy to projects that are designed to accomplish strategy execution.

Why Portfolio Management?

Year after year, organizations spend a considerable percentage of their budget on projects, most with significant IT components, with disappointing results.4 CIOs are under constant pressure to reduce IT costs and add value to the bottom line through IT products and services. There is no shortage of ideas to improve IT performance, and CIOs are struggling to determine the best approaches. Some of these approaches include outsourcing, implementing layoffs, allocating costs to user groups, standardizing technical platforms, improving project management capabilities, building enterprise architectures, implementing data warehouses, and providing web-based processing. The list goes on and on. The trick is for CIOs to use the best strategies with the least risk and the highest payback.

Choosing Among Change-Management Alternatives

One way to know how to choose the right change initiatives is to better understand the value of financial improvement alternatives for organizations that rely on significant IT support. In 2004, Eugene Lukac, then a partner in CSC’s Consulting Group (currently a Specialist Leader in Deloitte Consulting’s Strategy & Operations practice), suggested using an analytical framework to understand options:5

To understand the relative value of financial improvement options for IT, one needs an analytical framework that is rigorous and complete. Under such a framework, the effective management of IT is understood to involve converting the IT budget into IT resources, translating IT resources into IT output, and delivering business value from that IT output.

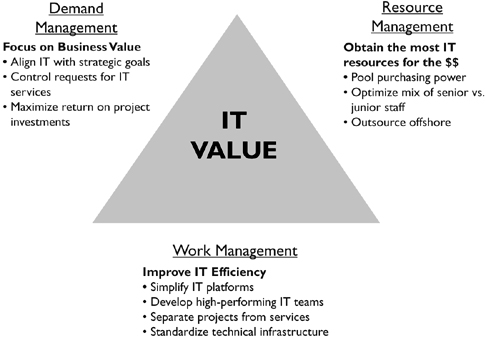

Lukac goes on to say that in using this decision framework, management has three possible “levers” to maximize the financial performance of IT:

Resource management. Strategies to manage resources include outsourcing major parts of the work, reorganizing the structure to flatten the organization and reduce managerial andadministrative expenses, and ensuring an optimum mix of senior, mid-level, and junior staff members.

Resource management. Strategies to manage resources include outsourcing major parts of the work, reorganizing the structure to flatten the organization and reduce managerial andadministrative expenses, and ensuring an optimum mix of senior, mid-level, and junior staff members. Work management. Strategies to manage the work include standardizing technology platforms and applications, employing Six Sigma practices to improve efficiency, investing in building high-performing teams, and separating projects from services.

Work management. Strategies to manage the work include standardizing technology platforms and applications, employing Six Sigma practices to improve efficiency, investing in building high-performing teams, and separating projects from services. Demand management. Strategies to control the demand for IT projects and services include implementing rigorous portfolio management techniques that align IT plans with the business strategic plans, ensure there is a sound return on IT project investments, control requests for new products and services from the business to IT, and minimize investments in low-value projects.

Demand management. Strategies to control the demand for IT projects and services include implementing rigorous portfolio management techniques that align IT plans with the business strategic plans, ensure there is a sound return on IT project investments, control requests for new products and services from the business to IT, and minimize investments in low-value projects.

Figure 2–1 depicts these levers.6

Figure 2–1 —Three Levers to Maximize the Business Value of IT

This “three-lever” framework provides a useful structure for management to make decisions in each area, track progress toward achieving the strategies, and track cost savings. Lukac contends that demand management is much more powerful in terms of cost savings than work management, which in turn is more powerful than resource management. This makes sense because the primary value IT contributes to the organization is working on the most valuable projects and services to help capture the benefits of new business opportunities.

Recent evidence shows that organizations have a tendency to pull the resource management lever first, outsourcing their work, even though outsourcing is fraught with problems and risk. Lukac appropriately contends that this is a worst practice. Unintended ramifications of outsourcing abound, manifested by poor morale, loss of employee trust, and strategic changes that revert to insourcing because of disappointing cost-reduction results.

For example, a recent CIO Magazine article tells the story of the global financial services company JPMorgan Chase, which negotiated a $5 billion contract to outsource much of its IT. Over time, the company faced soaring costs and management teams that were distracted from key ventures because they were spending years preparing for the IT transition to the outsourcing vendor. Due to disappointing results, JPMorgan Chase recently decided to bring its IT resources back in-house, a decision that then necessitated more time and additional, significant costs. 7 It was a costly mistake to invest so much of the company’s resources into outsourcing its IT programs.

All three levers should be used with the strongest emphasis on demand management, also known as portfolio management.

Why is Portfolio Management So Valuable?

Portfolio management—managing the demand for IT projects—provides the executive team with a system-wide view of projects across the enterprise, which makes it possible to make informed decisions about where to focus investments. To ensure that strategic goals create value, strategic goals and themes are translated into tangible programs and supporting projects through the portfolio management process. By aligning investments with projects that deliver outcomes to achieve strategic goals, portfolio management leads directly to improvements to the bottom line. The promise of project portfolio management is that for a given risk level, there is a specific mix of project investments that will achieve an optimal result.

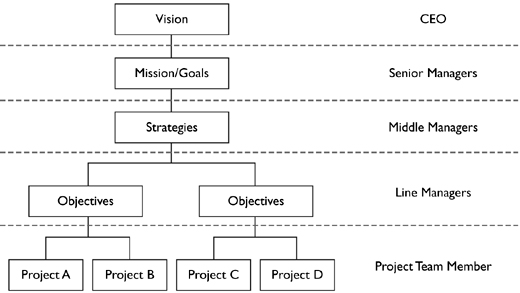

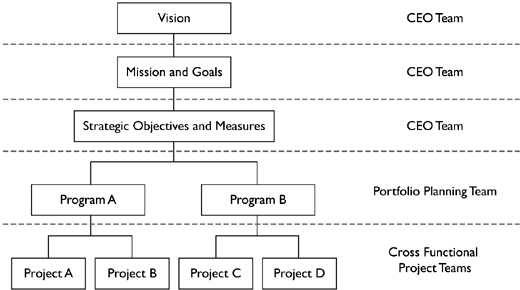

Through portfolio management, project management is elevated to a strategic management process. The strategic goals, themes, and measures established during the planning process become the drivers of future projects. Decisions for project investments are no longer made within the functional silos that exist in most corporations and governmental agencies. The portfolio planning team is accountable for creating the right investment path for the enterprise and continually managing the portfolio of projects. This reduces duplication of effort, resolves inconsistencies in project objectives and scope, and optimizes the mix and scheduling of projects. Figure 2–2 depicts where portfolio management fits in a strategically focused organization.

As Figure 2–2 demonstrates, implementing portfolio management in an organization connects all employees to corporate strategies. Cross-functional project teams are treated as critical strategic resources. Individuals and teams are given clear, quantifiable performance expectations when they apply their knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to create the project deliverables. Individual and team accountability is made clear.

As projects are launched, project managers are linked to strategic goals, themes, and measures. Project planning is focused on business-relevant outcomes. Project managers subdivide the overall project deliverables into smaller, measured outcomes until they are appropriate, individual assignments.

Figure 2-2—Strategie Project Management

Organizational Maturity Environment for Project Success

Studies have been conducted to get a feel for how pervasive this new management process has become. In a 2005 study of 54 senior-level decision makers, 57.4 percent of the respondents reported that portfolio management had helped their organization improve focus and select the optimal projects. In addition, 70.4 percent said it had improved project alignment with their organization’s overall strategy.8

The Business Analyst—Central to Effective Portfolio Management

Given the benefits of portfolio management, why aren’t all organizations successfully implementing portfolio management strategies? The most significant reason is that organizations often lack the necessary management information and the focus required to address the burden of analysis to make informed decisions. Senior business analysts use an effective set of tools and processes to communicate actionable information to portfolio management team members who require this information to make the best project investments. Without the rigorous business analysis leading up to significant investments in programs and supporting projects, decisions are made based simply on intuition. This places the return on project investment at risk.

The business analyst plays a significant role in helping the executive leadership team translate business strategies into new business change initiatives. Ideally, the business analyst guides an array of enterprise analysis activities that lead up to project selection and prioritization. The following section takes a more detailed look at the portfolio management process to further define the critical role of the business analyst.

Defining Portfolio Management

Project investment portfolio management aims to achieve the maximum return on project investments—much like a financial portfolio aims to achieve the maximum return on financial investments. According to the Federal CIO Council, portfolio management involves five key objectives:9

Defining goals and objectives—clearly articulating what the portfolio is expected to achieve. Aligning the portfolio goals to the strategic goals.

Defining goals and objectives—clearly articulating what the portfolio is expected to achieve. Aligning the portfolio goals to the strategic goals. Understanding, accepting, and making tradeoffs—determining how much to invest in one thing as opposed to something else.

Understanding, accepting, and making tradeoffs—determining how much to invest in one thing as opposed to something else. Identifying, eliminating, minimizing, and diversifying risk—selecting a mix of investments that will avoid undue risk, will not exceed acceptable risk tolerance levels, and will spread risks across projects and initiatives to minimize adverse impacts.

Identifying, eliminating, minimizing, and diversifying risk—selecting a mix of investments that will avoid undue risk, will not exceed acceptable risk tolerance levels, and will spread risks across projects and initiatives to minimize adverse impacts. Monitoring portfolio performance—understanding the progress that the portfolio is making toward the achievement of the goals and objectives.

Monitoring portfolio performance—understanding the progress that the portfolio is making toward the achievement of the goals and objectives. Achieving a desired objective—having confidence that the desired outcome will likely be achieved given the aggregate investments.

Achieving a desired objective—having confidence that the desired outcome will likely be achieved given the aggregate investments.

Let us examine the portfolio management activities that support these objectives.

The Portfolio Management Process

Using expert facilitation, senior business analysts define the process the portfolio management team will follow and ensure that all team members agree to it. Figure 2-3 provides a typical portfolio management process flow chart.

The portfolio management process should be as simple and straightforward as possible. Process components typically include:

Project proposal—submitting a new project idea for consideration. From strategic plans and goals, the senior business analyst facilitates a small team of business and technology experts to draft portfolio investment objectives either as proposed solutions to business problem or as plans to seize new business opportunities. Then the expert team identifies potential project approaches and analyzes the feasibility of each option before drafting a business case for the most feasible option.

Project proposal—submitting a new project idea for consideration. From strategic plans and goals, the senior business analyst facilitates a small team of business and technology experts to draft portfolio investment objectives either as proposed solutions to business problem or as plans to seize new business opportunities. Then the expert team identifies potential project approaches and analyzes the feasibility of each option before drafting a business case for the most feasible option. Project approval—reviewing, selecting, and prioritizing a proposed project. The portfolio management team makes adjustments to the portfolio if a new, approved project is a higher priority than current active projects. It may be necessary to reallocate resources from an active project, or even shut the active project down temporarily.

Project approval—reviewing, selecting, and prioritizing a proposed project. The portfolio management team makes adjustments to the portfolio if a new, approved project is a higher priority than current active projects. It may be necessary to reallocate resources from an active project, or even shut the active project down temporarily.

Figure 2-3—Portfolio Management Process Flow Chart

Resource allocation—allocating resources to high-priority projects first. The portfolio management team ensures that resources are properly allocated. Project resources are finite strategic assets—they can reach capacity and run out. Management must ensure that these vital corporate assets are deployed appropriately.

Resource allocation—allocating resources to high-priority projects first. The portfolio management team ensures that resources are properly allocated. Project resources are finite strategic assets—they can reach capacity and run out. Management must ensure that these vital corporate assets are deployed appropriately. Program reviews—conducting control gate reviews of ongoing projects. The portfolio management team conducts ongoing control gate reviews to revalidate the business case, review current estimates of cost and time, validate or refine the project priority, and make a go/no-go decision about funding the project for the next major phase. Phase-based funding—the practice of funding only the next phase rather than the entire project—is becoming an essential risk-mitigation strategy in the quest to manage project portfolios.

Program reviews—conducting control gate reviews of ongoing projects. The portfolio management team conducts ongoing control gate reviews to revalidate the business case, review current estimates of cost and time, validate or refine the project priority, and make a go/no-go decision about funding the project for the next major phase. Phase-based funding—the practice of funding only the next phase rather than the entire project—is becoming an essential risk-mitigation strategy in the quest to manage project portfolios. Project portfolio assessment—reviewing, assessing, and prioritizing the entire portfolio of projects. The portfolio management team conducts a periodic assessment of the entire portfolio of projects to revisit, reaffirm, or make adjustments to the portfolio of projects as events occur, competitive advances emerge, technology moves forward, and business strategies change.

Project portfolio assessment—reviewing, assessing, and prioritizing the entire portfolio of projects. The portfolio management team conducts a periodic assessment of the entire portfolio of projects to revisit, reaffirm, or make adjustments to the portfolio of projects as events occur, competitive advances emerge, technology moves forward, and business strategies change. Data management—storing, maintaining, and reporting information about the portfolio. The portfolio management team needs complete, accurate information in order to make the best decisions for the organization.

Data management—storing, maintaining, and reporting information about the portfolio. The portfolio management team needs complete, accurate information in order to make the best decisions for the organization.

So how does a robust portfolio management process impact project managers and project teams? Let us examine the power of strategically aligned projects.

Portfolio Management at the Project Level

As the portfolio management processes permeate the organization, project team members should begin to understand how their project aligns with organizational strategy. Project status reports feed directly into the categories of the strategic scorecard. Project managers are still responsible for project scope, quality, risk, cost, and schedule, as they have been traditionally. They now also partner with the business analyst to define how project results will align with strategic goals in the strategic plan and the business case.

For strategic projects, business analysts and project managers report directly to the executive project sponsor for ongoing direction and to the portfolio planning and management team for critical milestone control gate reviews. The filtering of information from the project manager up through the multi-layered functional chain of command is no longer required. Figures 2-4 and 2-5 depict these differences between the old hierarchical focus and the new strategic focus.

Figure 2–4—Old Hierarchical Focus

Too Many Layers:

Figure 2–5—New Strategic Focus

Strategic Management:

The executive project sponsor and the project team are accountable for business benefits. Project profitability—when project benefits exceed project and operational costs—is now the lowest unit of planning and control for the organization.

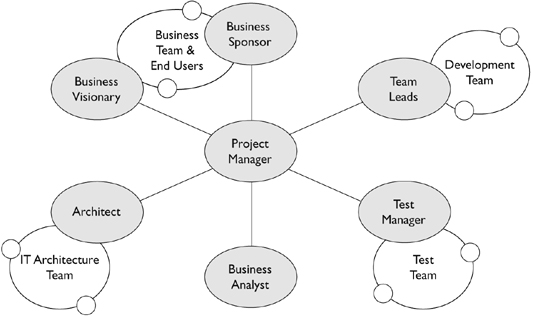

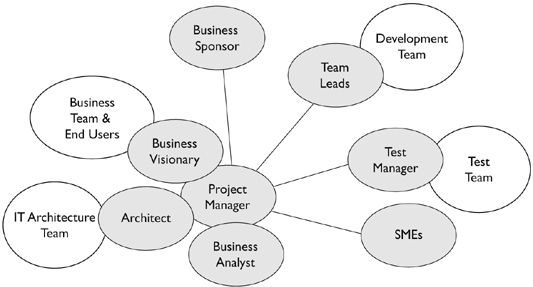

Under this new approach, cross-functional project teams become effective strategic tools employed by management to achieve goals. Consequently, management makes a considerable investment to build and sustain high-performing teams—small core project teams that are highly trained, multi-skilled, very experienced, and personally accountable. These core teams are small but mighty, co-located, and dedicated full-time to the project. This small, expert core team brings subject matter experts and subteams into the project at key points. The core team is empowered to make all project decisions. If the team encounters a barrier that is impeding forward progress, its project sponsor is just down the hall, available anytime, and committed to removing barriers in real time. Figures 2-6 and 2-7 depict the differences between the old and new project team structures.

Figure 2–6—Traditional Project Team Structure

Figure 2-7—Core Project Team Structure

In addition to building and sustaining high-performing teams, management must be alert to environmental obstacles to project success. Often, management must simplify and streamline processes, eliminate outmoded policies, and remove barriers to team performance to create the optimal change-adaptive culture in which project teams can thrive.

The Role of the Program Management Office

Ideally, a program management office (PMO), or a similar center of excellence, facilitates the portfolio management process as a small, dedicated group serving under the direction of the executive team. The PMO is typically staffed by senior technologists, business analysts, and project managers. This staff is a proactive internal business/technology consulting group that provides subject matter expertise in all aspects of strategy execution and portfolio management. In this role, the PMO spends its time facilitating and providing decision-support information to the portfolio management team. The goal is to ensure that the organization is investing in the right project mix. PMO portfolio management support activities include:

Developing and maintaining portfolio management processes and tools

Developing and maintaining portfolio management processes and tools Aggregating metric data and strategic scorecard data

Aggregating metric data and strategic scorecard data Maintaining and reporting information in portfolio databases

Maintaining and reporting information in portfolio databases Mapping portfolios

Mapping portfolios Preparing for and facilitating portfolio planning meetings

Preparing for and facilitating portfolio planning meetings Conducting feasibility, benchmark, and competitive studies

Conducting feasibility, benchmark, and competitive studies Preparing business cases for proposed projects

Preparing business cases for proposed projects Measuring the value project outcomes bring to the organization

Measuring the value project outcomes bring to the organization

In addition, the PMO spends a considerable amount of time providing execution support to the project teams managing the highest priority projects. The goal is to build high-performing teams that execute flawlessly, leading to the earliest possible launch of the new product or service to achieve the greatest value to the organization. PMO project team support activities include:

Facilitating project kickoff workshops

Facilitating project kickoff workshops Providing requirements elicitation and analysis support

Providing requirements elicitation and analysis support Coaching, mentoring, and team building

Coaching, mentoring, and team building Allocating resources

Allocating resources Managing risk

Managing risk Preparing for control gate reviews

Preparing for control gate reviews Facilitating and assisting team leadership

Facilitating and assisting team leadership Formatting, compiling, and publishing reports

Formatting, compiling, and publishing reports Providing formal and informal training

Providing formal and informal training

Implementing an effective portfolio management process is no easy endeavor. It is essentially an organizational transformation initiative, significantly changing the way projects are conducted. The next section examines proven strategies for successfully implementing portfolio management.

Implementation Strategies

Implementing portfolio management processes involves an organization-wide change management effort, which is often led by the leadership team, supported by senior business analysts and project managers from the PMO. Simply training and supporting a single group of project managers and business analysts is of little help over the long term if the organization as a whole doesn’t support the efforts and align them throughout. Likewise, it does not make sense to conduct rigorous strategic planning without a framework to link it to project teams and outcomes.

Implementing portfolio management is a significant endeavor requiring managers at all levels to change their way of selecting, investing in, and managing projects. The required cultural change can be painful and slow if the existing culture continues to determine the project selection methods. Implementing portfolio management requires success in several areas: soliciting executive support, taking inventory of and assessing the current projects in the portfolio, selecting and prioritizing new projects, and portfolio reporting.

Executive Support

Portfolio management implementation starts at the top and cascades down to all levels of the organization. To avoid false starts, the change initiative should be managed as a project. A formal portfolio management kickoff workshop brings together all key stakeholders, including the senior management team, functional managers who own project resources, senior project managers, business analysts, and other formal and informal leaders within the organization. The purpose of the workshop is to develop the charter and business case for implementing portfolio management and for establishing or expanding the role of the PMO.

Executive Seminars

Implementation should start at the top with an executive seminar that introduces the concepts and elements of strategic portfolio management. Such a seminar provides executives with awareness and education about where portfolio management fits in relation to other business management processes. The seminar should be designed to enable executives to arrive at consensus on moving forward to implement portfolio management. The seminar has several objectives, including introducing the idea of accompanying strategic planningwith a strategic execution framework, enhancing leadership and management awareness of the importance of portfolio management, reviewing all components of effective strategy execution, and emphasizing the importance of a strategy-driven and adaptive culture.

Executive seminars held to discuss portfolio management strategies typically cover the importance of robust and dynamic strategic planning processes that include formulating strategic measures and themes. Portfolio planning and management must ensure that project initiatives align with greater organizational strategies. Executive seminars should also emphasize that program and project management can help ensure flawless project execution, highlighting the critical role of executive oversight through ongoing monitoring and control.

Assuming the executive team decides to move forward to implement portfolio management initiatives, the senior team leads the implementation and the PMO or a similar decision-support group facilitates implementation.

Portfolio Inventory and Assessment

After securing management’s commitment to implement portfolio management, the PMO conducts a current-state analysis of active projects to determine which projects will be subjected to the portfolio management process. Serving as a resource to the portfolio management team, the PMO takes inventory of and organizes projects, making a first attempt at prioritizing them and preparing reports about the portfolio. The PMO also establishes a portfolio database to maintain an inventory of the projects in the portfolio, and implements a process to keep the information current.

The PMO first prioritizes projects by establishing boundaries to clearly define which projects will be subject to the portfolio management process. Corporate budgets usually allot only a limited amount of funding for department-specific initiatives managed within thebusiness units, so the portfolio management team must spend its time managing only major strategic initiatives. The projects subjected to rigorous portfolio management may include those that meet one or more of the following criteria:

The project is cross-functional in nature

The project is cross-functional in nature The project requires a significant investment of time and resources

The project requires a significant investment of time and resources The project is designed to achieve or advance one or more strategic goals

The project is designed to achieve or advance one or more strategic goals The project is high risk and/or involves new, unproven technology

The project is high risk and/or involves new, unproven technology

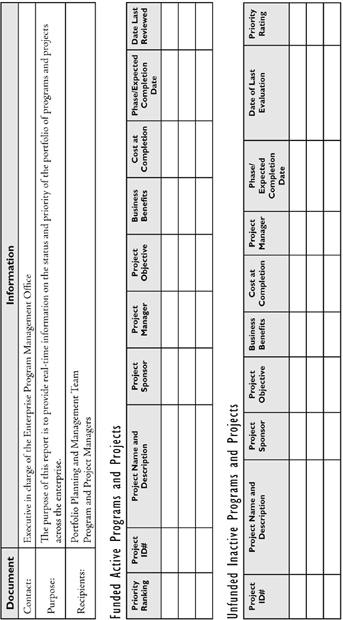

When conducting an inventory and quick assessment of the current state of portfolio projects, the business analyst should prepare a portfolio summary report describing the project characteristics listed in Figure 2-8.

Project Selection

Portfolio planning and management teams follow a structured decision-making methodology when selecting the portfolio of valuable projects. Because not all project proposals can be funded, selecting projects requires the framework of a predetermined, structured, and defined decision-making process. The business analyst employs sophisticated business analysis techniques to gather and present to the portfolio management team the information that the team requires to make informed project selection decisions. The decision-support process is accompanied by supporting tools for assessing and prioritizing projects.

Many organizations support well over $100 million in project investments per year to improve performance. In addition to new-product development projects, organizations have a portfolio of internal investments in IT, facilities, business process reengineering, new lines of business, corporate training, and cultural transformation initiatives. Portfolio management teams make the best investment decisions by focusing on three overarching project selection goals:

Figure 2–8—Portfolio Summary Report

Value maximization. Maximize the value of the entire portfolio in traditional financial terms.

Value maximization. Maximize the value of the entire portfolio in traditional financial terms. Strategic alignment. Break down project investments to ensure that they are appropriately tied to business strategies.

Strategic alignment. Break down project investments to ensure that they are appropriately tied to business strategies. Balance. Achieve the appropriate balance of projects in the portfolio.

Balance. Achieve the appropriate balance of projects in the portfolio.

Balance is perhaps the most difficult goal to achieve because portfolios are balanced according to different areas of business value. For example, a portfolio can be balanced by its types of projects (e.g., research and development, IT, new-product development, product-line enhancements), by the duration of its projects (e.g., long term, short term), by the risk level of its projects (e.g., high risk, “sure wins”), and by the number of its retooling projects (i.e., technology and/or business process improvement projects needed to remain competitive).

Project Prioritization

Once the projects that are worth including in the portfolio management process are chosen, that group of projects—the narrowed portfolio—must be prioritized. This step includes determining prioritization criteria based on strategic plans, goals, and performance measures. Typical prioritization criteria include organizational factors, cost/benefit analysis, customer satisfaction, stakeholder relations, risk analysis, technical uncertainty, and cultural change impact. If the organization does not have a mature strategic planning process, this step might be difficult. In such a case, it maybe necessary to hold to a strategic planning session to determine key strategic goals and measures.

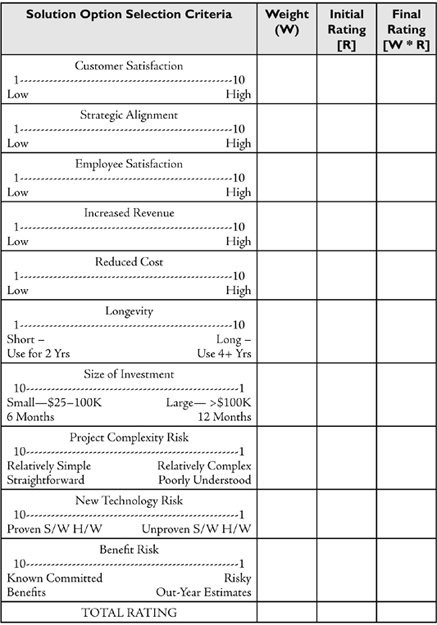

Decision-support tools and reports are designed to support portfolio assessments according to their business value.10 It is imperative that organizations use a project prioritization tool to assist in making project investment decisions. A senior business analyst from within the PMO develops and pilots a prototype project prioritization tool to ensure that the projects appear to be prioritized appropriately. The business analyst then adjusts the prioritization tool on the basis of the pilot results, and presents the prioritized list of projects and the project prioritization tool to the portfolio planning and management team for approval. Figure 2-9 offers a sample project ranking tool.

Portfolio Reporting

The PMO prepares an initial set of portfolio reports for presentation to the portfolio planning and management team. Elements in the reports typically include a list of projects ranked by priority, including summary information about each project obtained during the quick assessment; a status report for each project; and portfolio mapping reports. The PMO determines which kind of information will mean the most to the portfolio management team, and should continue to refine and improve that information as much as possible before delivering the report. Remember a golden rule: keep it simple.

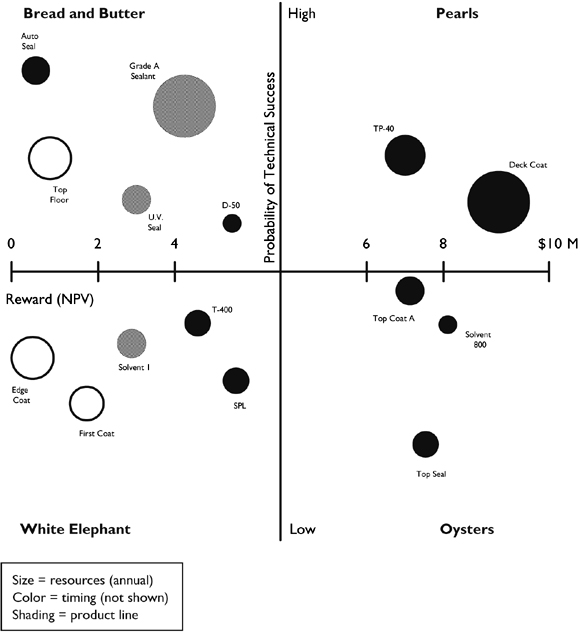

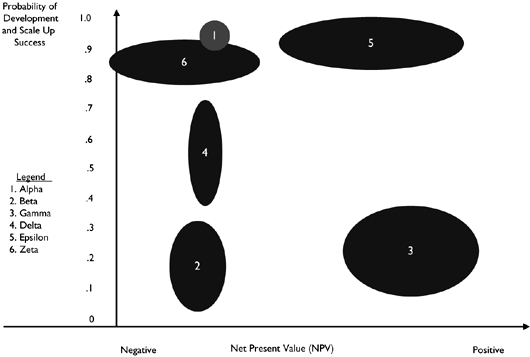

Portfolio reports and graphical maps are essential to make the entire portfolio of projects visible for executive assessment. Portfolio maps are effective tools to visually demonstrate the link between projects and strategic goals. Projects are designed to reach strategic goals, but the business analyst has to define that connection. In addition, portfolio maps are created to chart projects to strategic report categories, to risk levels, and according to financial return (e.g., net present value—cash value over a period of time, economic value added—how project deliverables affect earnings). Senior business analysts should place sufficient focus on procedural and cultural issues, keeping the process simple and straightforward to demonstrate the business value of disciplined portfolio management. Figures 2-10, 2-11, and 2-12 offer sample portfolio mapping reports.

Figure 2–9—Sample Project Ranking Tool

Legend:

1. Customer Satisfaction: impact of project on external customers

2. Business Results: impact of project on strategic goals

3. Employee Satisfaction: impact of project on employee retention

4. Revenue: impact of project on increased revenue

5. Cost: low versus high cost to fund the project

6. Longevity: length of time the enterprise will benefit from the new product or service

7. Size of Investment: large versus small investment risk

8. Project Complexity Risk: simple versus complex project

9. New Technology Risk: proven technology versus cutting edge/unproven

10. Benefit Risk: risk to realizing projected benefits

Implementing portfolio management is an arduous task. Many organizations have been unable to establish and maintain an effective practice to manage their project investments. Soliciting executive support, portfolio inventory and assessment, project selection, project prioritization, and portfolio reporting are all essential to success.

Challenges

Even well-established portfolio management systems encounter challenges. Difficulties include:

Too many off-strategy projects, disconnects between spending breakdowns and priorities

Too many off-strategy projects, disconnects between spending breakdowns and priorities

Figure 2–10—Portfolio Mapping Report – Market Attractiveness versus Ease of Implementation

Figure 2–11—Portfolio Mapping Report – Product Mix

Too many unfit, weak, mediocre projects; inadequate success rates at product launch

Too many unfit, weak, mediocre projects; inadequate success rates at product launch Weak go/no-go decisions, projects tend to take on a life of their own, poorly performing projects are not terminated

Weak go/no-go decisions, projects tend to take on a life of their own, poorly performing projects are not terminated Project density is too great, far too many projects for limited resources, cycle times and success rates suffer

Project density is too great, far too many projects for limited resources, cycle times and success rates suffer

Figure 2-12—Portfolio Mapping Report – Probability of Success versus Net Present Value

Inadequate resource planning and allocation processes, over-allocated project team members

Inadequate resource planning and allocation processes, over-allocated project team members Too many trivial projects in the new-product pipeline (e.g., modifications, updates, enhancements)

Too many trivial projects in the new-product pipeline (e.g., modifications, updates, enhancements) Not enough major-breakthrough, competitive-advantage projects, probably a result of reduced cycle time with insufficient resources

Not enough major-breakthrough, competitive-advantage projects, probably a result of reduced cycle time with insufficient resources Inability to measure investment metrics

Inability to measure investment metrics

As they help design and implement project portfolio management processes for their organizations, business analysts should pay special attention to these challenges and work to avoid or mitigate their impact. Using the best practices presented in the following section can help.

Best Practices

The following portfolio management best practices can go a long way toward preventing typical challenges. Failing to understand and follow these guidelines may compromise the overall portfolio management implementation process.

Strategic enterprise-wide focus—specific and measurable strategic goals as a foundation for selecting projects. After establishing strategic goals, themes, and measures, the business analyst should filter all major change initiatives through the portfolio management process to receive funding.

Simplicity—simple, straightforward portfolio management processes. Keeping portfolio management processes simple can facilitate their acceptance on an organizational level. Most executives have an aversion to complex processes and bureaucratic paperwork. The business analyst and the PMO can further assuage executive resistance by doing most of the work.

Early filtering criteria—basic requirements or watershed criteria. A project must fulfill basic requirements to be considered strategic and to become a candidate for selection and funding. For example, it’s important to confirm that the project delivers a cross-functional benefit. Other common filters include alignment with the organizational mission, business threshold minimums (e.g., ROI, cost/benefit ratio), and compliance with organizational constraints (e.g., current technology).

Standards—standard templates for the business case and project proposal. Use standard templates to ensure that decision-makers always review consistent information from project to project. This is essential to make defensible judgments on the project’s priority. See Appendix A for a sample business case template.

Project ranking tool—standard project assessment, selection, and prioritization tools. The project ranking decision-support tool usually contains ranking criteria that are based on strategic goals. Assign relative weights to each criterion, determine a project’s ranking basedon the criteria, and calculate a score (or priority rating) for each project. See Figure 2-9 for a sample project ranking tool.

Portfolio reviews—regular portfolio review meetings to ensure balance and strategic consistency among projects. Conduct portfolio review meetings to assess the entire portfolio for balance and strategic alignment, and to review new project proposals and ongoing project status at key checkpoints for go/no-go decisions.

Process support—support for the process in terms of process, tools, information and facilitation. A PMO, business analysis center of excellence, or a similar support group helps define and continuously improve portfolio management processes, maintain portfolio records, and prepare accurate decision-support information for the portfolio management team.

Investment analysis measures—measurement of the portfolio’s value to determine the return on project investments. Well-defined portfolios, audited results, and post-project benefit analyses are key to understanding the actual value of portfolio investments and management practices.

These best practices are essential for success. Organizations lacking in sophisticated business analysis practices are at risk. As IT governance becomes an adopted practice, robust portfolio management practices are indispensable management tools.

Part II builds on the portfolio management methods described in this chapter, and delves deeper into more advanced portfolio management techniques organizations may use depending on the maturity of their portfolio management and business analysis practices.

Endnotes

1. David P. Norton. “Project Balanced Scorecards—A Tool for Alignment, Teamwork and Results,” ProjectWorld & The World Congress for Business Analysts Conference Proceedings, November 17, 2005. Orlando, FL.

3. Ibid.

4. Kathleen B. Hass. Professionalizing Business Analysis: Breaking the Cycle of Challenged Projects, 2008. Vienna, VA: Management Concepts.

5. Eugene Lukac. “Avoiding Worst Practices in IT Spending,” CSC World, September-November 2004. Online at www.csc.com/aboutus/cscworld/sept_nov_04/articles/

avoiding_worst_practices_septnov04.pdf (accessed March 7, 2006).

6. Ibid.

7. Stephanie Overby. “Backsourcing Pain,” CIO Magazine, October 11, 2005. Online at http://www.cio.com.au/index.php/id;1796120911;fp;16;fpid;0 (accessed August 15, 2007).

8. Center for Business Practices. Project Portfolio Management Maturity: A Benchmark of Current Business Practices. Havertown, PA: Center for Business Practices, June 2005. Online at http://whitepapers.zdnet.com/whitepaper.aspx?&compid=9785&docid=158347 (accessed September 19, 2007).

9. Federal CIO Council. A Summary of First Practices and Lessons Learned in Information Technology Portfolio Management, March 2002. Online at http://www.cio.gov/documents/BPC_portfolio_final.pdf (accessed August 18, 2007).

10. R.G. Cooper, S.J. Edgett, and E.J. Lleinschmidt, “Portfolio Management in New Product Development: Lessons from the Leaders, Phase I,” Project Portfolio Management, Selecting and Prioritizing Projects for Competitive Advantage, James S. Pennypacker and Lowell D. Dye, editors, 1999. Havertown, PA: Center for Business Practices.