Chapter 4

Using Feasibility Studies to Determine the

Most Valuable Business Solution

In This Chapter:

Defining the Feasibility Study

Why Conduct a Feasibility Study?

Conducting a Feasibility Study

Challenges

Best Practices

Organizations work hard to stay informed, analyze the most current information, and transform their businesses to keep pace with the rapidly changing competitive landscape. Business success depends on the ability to continually update and reinvent organizational thinking, analyze the current organizational state, and plan for the future. These challenges require innovative thought and a structured and deliberate business analysis process.

Strategic planning and the creation of a to-be business architecture provide a firm foundation for understanding where an organization is today and where it wants to be in the future. From this foundation, organizations must select the best initiatives to manage the changes necessary to reach goals as quickly as possible, and with the least cost and risk.

Defining the Feasibility Study

Feasibility studies are often used to crystallize new business opportunities, identify alternative solution options, and determine which options to pursue to reach organizational goals. Feasibility studies are fast becoming an essential business planning technique for executing strategy. The business analyst incorporates feasibility studies into the portfolio management process, making project selection more effective.

A feasibility study is an analysis effort that applies the disciplines of market research and statistical analysis to understand the competitive environment, enabling an organization to make sound decisions about improvements and new ventures. The most effective feasibility studies systematically collect and analyze data about the market—its trends and threats—to facilitate business decision-making. Feasibility studies use verifiable information and apply statistical measures to ensure a complete and accurate analysis.

A recent web search produced several definitions for feasibility study, revealing a variety of uses:1

A likelihood study. A way to determine if a business idea is capable of being achieved. The study asks, “Can it work and produce the level of profit necessary?”

A likelihood study. A way to determine if a business idea is capable of being achieved. The study asks, “Can it work and produce the level of profit necessary?” A study of the applicability or practicability of a proposed action or plan.

A study of the applicability or practicability of a proposed action or plan. An analysis of the business area to determine whether a system can cost-effectively support the business requirements.

An analysis of the business area to determine whether a system can cost-effectively support the business requirements. A detailed investigation and analysis of a proposed development project to determine whether it is viable both technically and economically.

A detailed investigation and analysis of a proposed development project to determine whether it is viable both technically and economically. A study that determines if the information system makes sense for the organization from an economic and operational standpoint.

A study that determines if the information system makes sense for the organization from an economic and operational standpoint. A market study and an economic analysis combined to provide an investor with knowledge about both the project environment and the project’s expected return on investment.

A market study and an economic analysis combined to provide an investor with knowledge about both the project environment and the project’s expected return on investment. An examination of a particular project or business to assess its chances of operating successfully, before committing large amounts of money to it.

An examination of a particular project or business to assess its chances of operating successfully, before committing large amounts of money to it. An investigation into the economic environment, internal and external pressures, systems, procedures, and communication capability in a business area within a firm, to help corporate managers evaluate possible benefits of implementing a business or system change; an integral part of a corporate implementation plan.

An investigation into the economic environment, internal and external pressures, systems, procedures, and communication capability in a business area within a firm, to help corporate managers evaluate possible benefits of implementing a business or system change; an integral part of a corporate implementation plan.

These definitions all have a similar emphasis: feasibility studies consider a business problem or an opportunity and potential solutions before an implementation project is funded, to increase confidence in the project. Businesses spending millions of dollars on large-scale change initiatives every year are now realizing that a more rigorous analysis of the solution alternatives greatly increases the probability of a high return on project investments.

Why Conduct a Feasibility Study?

Most often, a feasibility study is commissioned to determine the viability of a new business opportunity. During strategic planning, executives may reference the information from feasibility studies to develop strategic plans, goals, and themes to achieve a future vision. During enterprise analysis, the portfolio management team may use feasibility studies to determine the best investment strategy needed tosolve business problems and seize new business opportunities. During the requirements and design phases, feasibility studies may be used to help conduct tradeoff analysis among solution alternatives.

When formulating a major business transformation project (e.g., forming a new line of business, increasing market share through acquisition, developing a new product or service), feasibility studies greatly assist in identifying the vast array of alternative solutions. Lower-risk change initiatives usually require much more abbreviated studies.

The feasibility study is usually undertaken to add a more rigorous analysis methodology to solution options presented in the business case for proposed new initiatives. As a result, the business case and the feasibility study usually present similar information.

Conducting A Feasibility Study

Although the typical activities required to conduct a thorough feasibility study appear to be sequential, they are often conducted concurrently and iteratively; in some cases, certain steps can be omitted. The amount of rigor depends on the complexity, risk, and criticality of the effort. Typical steps include the following:

Determine the business drivers for the feasibility study.

Plan the feasibility study activities.

Define the current state of the organization and the competitive environment.

Identify solution options.

Analyze each solution option.

Prepare feasibility study reports.

Determine the Business Drivers for the Feasibility Study

Feasibility studies are used to help determine the optimum solution for various business initiatives. Businesses undertake major change initiatives either to solve a business problem or to take advantage of a business opportunity. Enterprise analysis activities may identify a business problem or a business opportunity. A business problem typically emerges from business operations. For example, a particular business process may be failing to meet certain expectations.

In other cases, a new business opportunity identified during strategic planning and goal setting may appropriately lead to a study to determine whether pursuing the opportunity would be a wise venture economically, technologically, and operationally. A business opportunity could be introducing a new product or service, or expanding to create a new line of business.

Commissioning a Feasibility Study to Solve a Business Problem

Typical steps in determining whether to commission a feasibility study to solve a business problem include the following:

Identify the sponsor who is shepherding (and likely funding) the study.

Identify the sponsor who is shepherding (and likely funding) the study. Document the problem in as much detail as possible.

Document the problem in as much detail as possible. Determine any adverse impacts the problem is causing within the organization, and quantify those impacts (e.g., potential lost revenue, inefficiencies).

Determine any adverse impacts the problem is causing within the organization, and quantify those impacts (e.g., potential lost revenue, inefficiencies). Determine how quickly the problem could potentially be resolved, and the cost of doing nothing.

Determine how quickly the problem could potentially be resolved, and the cost of doing nothing. Conduct a root cause analysis to determine the underlying source of the problem.

Conduct a root cause analysis to determine the underlying source of the problem. Determine the potential areas of investment required to address the problem.

Determine the potential areas of investment required to address the problem. Draft a requirements statement describing the business need for a solution to the problem.

Draft a requirements statement describing the business need for a solution to the problem. Determine the potential areas of investment required to address the problem (e.g., business process reengineering, acquisition of an existing business, new and improved technology).

Determine the potential areas of investment required to address the problem (e.g., business process reengineering, acquisition of an existing business, new and improved technology). Determine the methodology or approach needed to complete the feasibility study.

Determine the methodology or approach needed to complete the feasibility study. Determine the resources required and time needed to complete the study.

Determine the resources required and time needed to complete the study. Propose the study to an appropriate sponsor.

Propose the study to an appropriate sponsor.

Commissioning a Feasibility Study to Take Advantage of a Business Opportunity

Typical steps in determining whether to commission a feasibility study to exploit a business opportunity include the following:

Identify the sponsor who is shepherding (and likely funding) the study.

Identify the sponsor who is shepherding (and likely funding) the study. Define the opportunity in as much detail as possible, including the events that led up to the discovery of the opportunity, and the business benefits expected if the opportunity is pursued.

Define the opportunity in as much detail as possible, including the events that led up to the discovery of the opportunity, and the business benefits expected if the opportunity is pursued. Quantify the expected benefits in terms (e.g., increased revenue, reduced costs).

Quantify the expected benefits in terms (e.g., increased revenue, reduced costs). Determine how quickly the business opportunity could be exploited and the cost of doing nothing.

Determine how quickly the business opportunity could be exploited and the cost of doing nothing. Determine the methodology or approach needed to complete the feasibility study.

Determine the methodology or approach needed to complete the feasibility study. Determine the potential areas of investment required to address the situation (e.g., business process reengineering, acquisition of an existing business, new and improved technology).

Determine the potential areas of investment required to address the situation (e.g., business process reengineering, acquisition of an existing business, new and improved technology). Draft a requirements statement describing the business need for pursuing the opportunity.

Draft a requirements statement describing the business need for pursuing the opportunity. Determine the resources required and time needed to complete the study.

Determine the resources required and time needed to complete the study. Propose the study to the appropriate sponsor.

Propose the study to the appropriate sponsor.

Plan the Feasibility Study Activities

As the business analyst embarks upon the effort to plan and execute the feasibility study, it is wise to first build a core team of subject matter experts (SMEs) to serve as a study team. Planning and executing a major feasibility study requires a wide range of skills and techniques that the business analyst might not possess. As a result, it’s best to enlist a team of experts who pay strong attention to detail, as well as provide business architecture skills, research and statistical analysis skills, business and technical writing skills, leadership, organization, and team-building skills, adaptability and change management skills, and communications skills. A strong, relevant knowledge of the industry and the organizational vision, mission, strategic goals, and organizational policies and procedures are also important, as is a broad understanding of the technology that supports the business.

Having a well-rounded team with requisite skills and knowledge ensures that the data gathered and analysis conducted represent thecollective wisdom of both experienced business and technology professionals. Core team members typically include:

Project manager—Even though a project manager isn’t assigned until after a project is officially commissioned, it’s important to consult an experienced project manager to help develop the project scope and to prepare time and cost estimates.

Project manager—Even though a project manager isn’t assigned until after a project is officially commissioned, it’s important to consult an experienced project manager to help develop the project scope and to prepare time and cost estimates. Business visionary—Involve a business SME who is a creative thinker and a futurist, one who represents the business area under consideration. This SME will help identify and evaluate the solution options and determine the best approach among feasible alternatives, determine business boundaries for the change initiative, and forecast the business benefits expected from the project outcome.

Business visionary—Involve a business SME who is a creative thinker and a futurist, one who represents the business area under consideration. This SME will help identify and evaluate the solution options and determine the best approach among feasible alternatives, determine business boundaries for the change initiative, and forecast the business benefits expected from the project outcome. Chief technologist—Involve a technology SME who is a visionary and advocate of advanced technology to achieve a competitive advantage. This SME will help craft technically feasible alternative solution options, determine the best option, and estimate the cost of acquiring or building the solution.

Chief technologist—Involve a technology SME who is a visionary and advocate of advanced technology to achieve a competitive advantage. This SME will help craft technically feasible alternative solution options, determine the best option, and estimate the cost of acquiring or building the solution. Financial Analyst—Involve a senior financial analyst to help prepare a cost/benefit analysis to demonstrate the economic viability of the proposed project.

Financial Analyst—Involve a senior financial analyst to help prepare a cost/benefit analysis to demonstrate the economic viability of the proposed project.

After assembling a core study team, begin planning the feasibility study by determining the decision criteria used to formulate options for consideration, evaluate those options, and determine the business objectives the solution must satisfy. At this point the study team conducts typical planning steps:

Start with the end in mind. Determine the format for the feasibility study report. It is important to define the scope and contents of the report during the planning stage to ensure thatall of the most important information will be generated during the study.

Start with the end in mind. Determine the format for the feasibility study report. It is important to define the scope and contents of the report during the planning stage to ensure thatall of the most important information will be generated during the study. Identify and document all activities needed to complete the feasibility study.

Identify and document all activities needed to complete the feasibility study. Review work-to-date with the sponsor to validate that the study requirements, plans, objectives, benefit criteria, and evaluation measures will meet the business need.

Review work-to-date with the sponsor to validate that the study requirements, plans, objectives, benefit criteria, and evaluation measures will meet the business need.

Define the Current State of the Organization and the Competitive Environment

The study team conducts an internal current-state analysis, as well as an external competitive analysis, as the first step of the actual feasibility study. This analysis may include a review of the current business architecture, including information about business objectives, strategy, and vision, an analysis of current business processes, and/or an assessment of future business architecture documentation. The current-state assessment typically considers the following elements, depending on the nature and scope of the study:

The business vision, strategy, goals, and measures

The business vision, strategy, goals, and measures The objectives of each line of business that has a stake in the area under study (collect relevant organization charts)

The objectives of each line of business that has a stake in the area under study (collect relevant organization charts) The physical location of each impacted line of business

The physical location of each impacted line of business The major types of business information required

The major types of business information required Current relevant business applications and supporting technologies, including technology architecture diagrams depicting the interfaces between current business technologies

Current relevant business applications and supporting technologies, including technology architecture diagrams depicting the interfaces between current business technologies Current (relevant) business processes, including process flow diagrams depicting the flow of process steps needed to complete a business function

Current (relevant) business processes, including process flow diagrams depicting the flow of process steps needed to complete a business function

Defining the current state is expedited if business architectural components for the current state of the organization are already complete and up-to-date. If this is not the case, the documentation developed during the current-state assessment can serve as a basis for developing the business architecture. Most of the techniques used to develop the business architecture are applicable to current-state assessments prior to the feasibility study.

The study team conducts an analysis of the external business environment, including a competitive analysis, an analysis of market trends and emerging markets, new and emerging technologies, and recent changes in the regulatory environment. The study team also conducts external research about the potential opportunity or business problem to uncover industry-specific information, industry benchmarks, risks, and results of similar attempts implemented by others.

Identify Solution Options

After defining the internal current state of the organization and the external competitive environment, the study team identifies potential solutions that could meet the business objectives. During this stage, the business analyst conducts frequent brainstorming sessions with the study team and any additional SMEs who may add value to the discovery session. This is the most creative portion of the feasibility study. Don’t worry if there is a certain amount of chaos and churn during this creative stage, because it stimulates creative thinking. The most innovative solutions are also likely to be the most complex; allow the group to spend some time at the edge of chaos.

It is important for the business analyst to create an environment that stimulates originality and focuses on future possibilities to identify the most creative solutions. Persons with a predeterminedbias toward a certain solution should probably not be invited to participate in this portion of the study, to prevent undue influence over the final recommendations.

Analyze Each Solution Option

Once all potential solution options have been identified, the group of experts transitions from brainstorming to analysis. Each solution option is analyzed for economic, technical, operational, cultural, and legal feasibility. The benefits, costs, risks, issues, assumptions, and constraints associated with each solution option are described in detail and compared against other options to determine the most viable solution.

Solution Feasibility

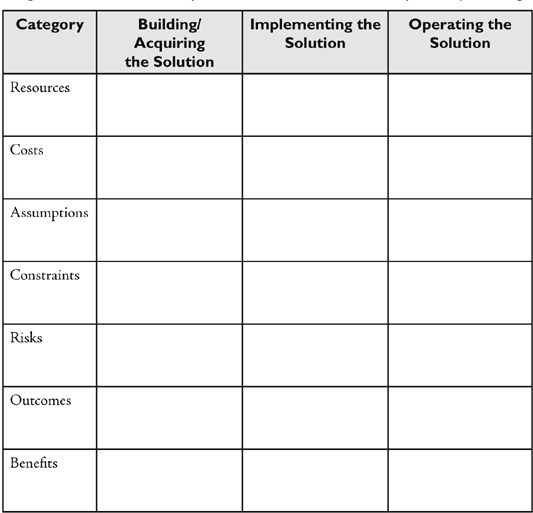

Describe the feasibility of each solution option—in both the business and technical environments—by indicating the resource requirements, costs, assumptions, constraints, risks, business outcomes, and business benefits for each of three phases: (1) building or acquiring the solution option, (2) implementing the solution option, and (3) operating the solution option.

Numerous techniques help in assessing the feasibility of each option, including:

Market surveys that prove current market acceptance and to forecast demand

Market surveys that prove current market acceptance and to forecast demand Technology advancement analysis to examine the latest technical capabilities, and to ensure the solution is not beyond the current limits of technology

Technology advancement analysis to examine the latest technical capabilities, and to ensure the solution is not beyond the current limits of technology COTS (commercial off-the-shelf) software package compare/contrast analysis

COTS (commercial off-the-shelf) software package compare/contrast analysis Business staff interviews to determine operational feasibility in the workplace

Business staff interviews to determine operational feasibility in the workplace IT staff interviews to determine operational feasibility in the technical operating environment

IT staff interviews to determine operational feasibility in the technical operating environment Finance staff and project manager interviews to ensure economic feasibility

Finance staff and project manager interviews to ensure economic feasibility Prototype projects to build a component of the proposed solution to prove that (at least) high-risk components of the proposed solution are technically feasible

Prototype projects to build a component of the proposed solution to prove that (at least) high-risk components of the proposed solution are technically feasible Risk identification, assessment, ranking, and response planning

Risk identification, assessment, ranking, and response planning Benchmark analysis to determine best-in-class practices

Benchmark analysis to determine best-in-class practices Competitive analysis to examine the potential market success of the solution

Competitive analysis to examine the potential market success of the solution Environmental impact analysis

Environmental impact analysis Early cost versus benefit analysis (which will be covered in more detail under the task to develop the business case)

Early cost versus benefit analysis (which will be covered in more detail under the task to develop the business case) Issue identification, assessment, ranking, and response planning

Issue identification, assessment, ranking, and response planning

Typically, analysis matrices or logs are used to capture the results of the feasibility analysis. The same type and level of information is documented for each solution option. See Figure 4-1 for a summary solution feasibility analysis log.

Figure 4–1—Summary Level Solution Feasibility Analysis Log

Subsidiary analysis logs may also be developed to provide the rationale for the estimates provided in the summary-level log presented in Figure 4-1.

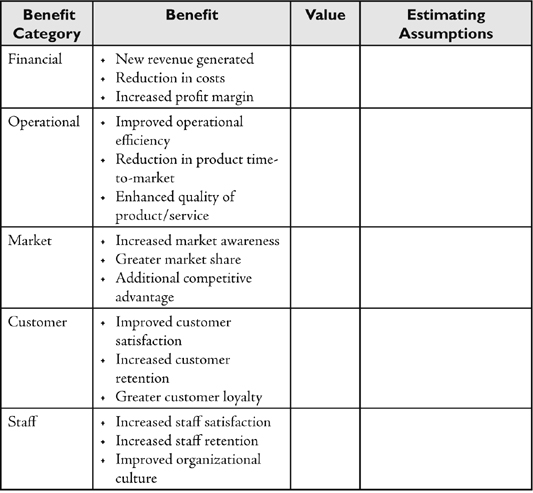

Solution Benefits

Describe any tangible (e.g., quantifiable in terms of cost savings or increased revenue) and intangible benefits (e.g., employee morale or customer satisfaction) to the organization that may result if the solution option is implemented. The estimates provided by the feasibility study are intended to be preliminary; estimates become more precise when completing the business case. Figure 4-2 presents a sample solution benefits log. As you can see, there may be numerous benefit categories.

Figure 4–2—Solution Benefits Log

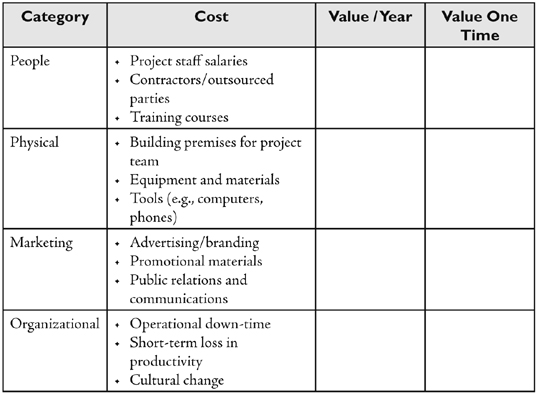

Solution Costs

Describe any tangible and intangible costs to the organization that may result if the solution option is implemented. Include the costs of the actual project (e.g., equipment procured); and include any negative impact caused by the delivery of the project (e.g., operational down-time).

Here again, the estimates provided by the feasibility study are preliminary; estimates become more precise when completing the business case. Figure 4-3 presents a sample solution costs log. Note that the log includes value/year, (e.g., increased revenue each year) versus value one time, (e.g., a one time cost saving from the sale of a facility).

Figure 4–3—Solution Costs Log

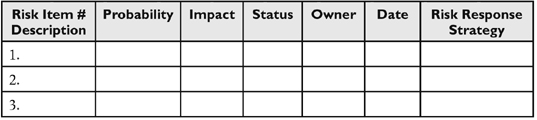

Solution Risks

Solution risks describe the most apparent risks to the organization if the solution option is implemented. Risks may be strategic, cultural, environmental, financial, operational, technical, industrial, competitive, or customer-related. Figure 4-4 presents a sample solution risks log.

Figure 4—4—Solution Risks Log

Solution Issues

Finally, solution issues describe any high-priority issues associated with this solution option. An issue is an identified event that will likely adversely affect the ability of the solution to produce required deliverables. Figure 4-5 presents a sample solution issues log.

Figure 4–5—Solution Issues Log

Solution Assumptions and Constraints

Assumptions help to fill gaps in information; they describe information that is assumed to be true, but can not be validated (e.g., a required skillset is readily available). Constraints describe any major limitations to the solution’s implementation (e.g., a standard technical platform).

Determine the Most Viable Solution

The expert team then reviews all of the feasibility data about each potential solution option and determines the best alternative. If there is no clear best option, the business analyst facilitates the expert team to arrive at a consensus on the alternative solution to recommend to the sponsor. The team identifies additional criteria and reviews it to distinguish between the options. The team then shares the results of the feasibility studies with the sponsor for approval to proceed with analysis activities that build a business case for a recommended solution.

Prepare Feasibility Study Reports

All of the information captured during the feasibility study is collected in a report that identifies each of the solution options available and rates each option’s likelihood of achieving the desired results. The Appendixes section offers a template feasibility study report, as well as more formal templates for the risk, issue, and decision logs that can be used to document any study team decisions.

An executive summary

An executive summary A statement defining the business problem or opportunity, including the requirement statement describing the business need for either a solution to the problem or for pursuing the opportunity

A statement defining the business problem or opportunity, including the requirement statement describing the business need for either a solution to the problem or for pursuing the opportunity Decision criteria used to formulate options for consideration

Decision criteria used to formulate options for consideration Information gathered during the current-state analysis and during the analysis of the greater competitive environment

Information gathered during the current-state analysis and during the analysis of the greater competitive environment A list of solution options

A list of solution options The feasibility analysis results for each solution option, including:

The feasibility analysis results for each solution option, including: A complete description of the solution option

A complete description of the solution option A complete description of the assessment process and methodology

A complete description of the assessment process and methodology A list of benefits provided by the solution option

A list of benefits provided by the solution option A list of costs to the organization

A list of costs to the organization A list of identified risks associated with the solution option

A list of identified risks associated with the solution option A list of identified issues that, once the solution option is implemented, could adversely impact the success of the solution

A list of identified issues that, once the solution option is implemented, could adversely impact the success of the solution A description of any major assumptions and/or constraints associated with this solution option

A description of any major assumptions and/or constraints associated with this solution option An alternative solution ranking, including the ranking criteria and scores for each option (Appendix F offers a project ranking tool template)

An alternative solution ranking, including the ranking criteria and scores for each option (Appendix F offers a project ranking tool template) The study results, including the recommended solution and any rationale for the decision

The study results, including the recommended solution and any rationale for the decision An appendix containing all supporting documentation (e.g., analysis logs)

An appendix containing all supporting documentation (e.g., analysis logs)

Additional information in the report may include:

The solution option’s strategic ties to the organization’s strategy, direction, and mission

The solution option’s strategic ties to the organization’s strategy, direction, and mission The solution option’s technological alignment with the organization’s current architecture standards.

The solution option’s technological alignment with the organization’s current architecture standards. The availability of COTS (commercial off-the-shelf) software packages

The availability of COTS (commercial off-the-shelf) software packages The extent to which existing business solutions will change

The extent to which existing business solutions will change

As the practice of portfolio management matures in business organizations, there will be a greater need to conduct feasibility studies for large-scale change initiatives. Conducting this kind of rigorous analysis provides a great deal of insight into the likelihood of project success prior to the authorization of funds. However, few organizations are investing in rigorous enterprise analysis prior to project approval, likely due to the challenges cited below.

Challenges

Common barriers to the successful completion of feasibility studies include the following:

Difficulty in securing sponsorship for the feasibility study

Difficulty in securing sponsorship for the feasibility study Cultural resistance: “It is not the way we do things around here.”

Cultural resistance: “It is not the way we do things around here.” Incomplete business architecture components; they are necessary to complete the current-state assessment

Incomplete business architecture components; they are necessary to complete the current-state assessment Lack of process to fund or resource studies of this magnitude

Lack of process to fund or resource studies of this magnitude Insufficient time is allotted for the study

Insufficient time is allotted for the study Insufficient knowledge by the study team about feasibility studies, and lack of skills needed to plan and conduct a meaningful study

Insufficient knowledge by the study team about feasibility studies, and lack of skills needed to plan and conduct a meaningful study

Best Practices

As feasibility studies become more prevalent, best practices have been identified to conduct them successfully:

Use both qualitative and quantitative analysis to compare the organization to others in the same industry, and to compare various solution options

Use both qualitative and quantitative analysis to compare the organization to others in the same industry, and to compare various solution options Use standard scientific investigative research practices

Use standard scientific investigative research practices Compare and contrast various elements of the study

Compare and contrast various elements of the study Use proven quality-enhancing techniques (e.g., Six Sigma).

Use proven quality-enhancing techniques (e.g., Six Sigma).

As we have discovered, the practice of conducting feasibility studies prior to making significant investments can serve a company well. World-class organizations are conducting detailed market investigations and feasibility studies of a proposed project to determine whether an identified solution can cost effectively support business requirements. Once the feasibility study is complete, the team goes on to create the business case (discussed in detail in the next chapter) that provides the investment governance group (the portfolio management team) with knowledge of both the environment where the project exists and the expected return on investment to be derived from it.

Endnotes

1. Referenced websites include: U.S. Small Business Association (http://www.sba.gov/library/sbaglossary.html#F); Bureau of Justice Assistance, Center for Program Analysis (http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/BJA/evaluation/glossary/

glossary_f.htm;) Webopedia (http://www.webopedia.com/TERM/S/SSADM.html); Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (http://commpres.env.state.ma.us/content/glossary.asp); and the Oregon Innovation Center (www.oregoninnovation.org/pressroom/glossary.d-f.html).