Chapter Fifty-Three

Revise Your Path to Publication

Assessing Your Current Trajectory and Adjusting for the Best Outcome

Don’t you wish someone could tell you how close you are to getting published? Don’t you wish someone could say, “If you just keep at it for three more years, you’re certain to make it!”?

Or, even if it would be heartbreaking, wouldn’t it be nice to be told that you’re wasting your time, so that you could move on, try another tack, or simply write what brings you personal pleasure, with no other aim in mind?

I’ve counseled thousands of writers over the years, and even if it’s not possible for me to read their work, I can usually say something definitive about what their next steps should be. I often see when they’re wasting their time.

No matter where you are on your own publishing path, it’s smart to periodically take stock of where you’re headed and revise as necessary. Here are some steps you can take to do just that.

RECOGNIZING STEPS THAT AREN’T MOVING YOU FORWARD

Let’s start with five common time-wasting behaviors. You may be guilty of one or more. Most writers have been guilty of the first.

Time-Waster 1: Submitting Manuscripts That Aren’t Your Best Work

Let’s be honest. We all secretly hope that some editor or agent will read our work, drop everything, and call us to say: This is a work of genius! YOU are a genius!

Few writers give up on this dream entirely, but to increase the chances of this happening, you have to give each manuscript everything you’ve got, with nothing held back. Too many writers save their best effort for some future work, as if they were going to run out of good material.

You can’t operate like that.

Every single piece of greatness must go into your current project. Be confident that your creative well is going to be refilled. Make your book better than you ever thought possible—that’s what it needs to compete. It can’t be good. “Good” gets rejected. Your work has to be the best.

How do you know when it’s ready, when it’s your best? I like how Guide to Literary Agents editor Chuck Sambuchino typically answers this question at writing conferences: “If you think the story has a problem, it does—and any story with a problem is not ready.”

It’s common for a new writer who doesn’t know any better to send off his manuscript without realizing how much work is left to do. But experienced writers are usually most guilty of sending out work that is not ready. Stop wasting your time.

Time-Waster 2: Self-Publishing When No One Is Listening

There are many reasons writers choose to self-publish, but the most common is the inability to land an agent or a traditional publisher.

Fortunately, it’s more viable than ever for a writer to be successful without a traditional publisher or agent, primarily due to the rise of e-books and e-readers. However, when writers chase self-publishing as an alternative to traditional publishing, they often have a nasty surprise in store: No one is listening. They don’t have an audience.

Bowker estimated that in 2009, more than 760,000 new titles were “nontraditionally” published, which included print-on-demand and self-published work. How many new titles were traditionally published? About 288,000. And none of these numbers take into account the growing number of writers releasing their work in electronic-only editions.

If your goal is to bring your work successfully to the marketplace, it’s a waste of time to self-publish that work—in any format—if you haven’t yet cultivated an audience for it or can’t market and promote it effectively through your network. Doing so will not likely harm your career in the long run, but it won’t move it forward, either.

Time-Waster 3: Publishing Your Work Digitally When Your Audience Wants Print

E-books have become the darlings of the self-publishing world, and for good reason. They’re easy to create, require little investment, and can reach an international market overnight. They also allow you to experiment, to have a direct line to a readership, and to see what effectively grows that readership.

But it won’t do you a bit of good if your audience is still devoted to print. If you don’t know what format your readers prefer, then find out before you waste your time developing a product no one will read or buy.

Rework this maxim as needed for your particular audience (e.g., don’t focus on producing print if your readers favor digital).

Time-Waster 4: Looking for Major Publication of Regional or Niche Work

Every year agents receive thousands of submissions for work that does not have national appeal and does not deserve shelf space at every chain bookstore in the country. (And that’s typically why you get an agent: to sell your work to the big publishers, which specialize in national distribution and marketing.)

As a writer, one of the most difficult tasks you face is gaining sufficient distance from your work to understand how a publishing professional would view the market for it, or to determine if there’s a commercial angle to be exploited. You have to view your work not as something precious to you but as a product to be positioned and sold. That means pitching your work only to the most appropriate publishing houses, even if they’re in your own backyard rather than New York City.

Signs You’re Getting Closer to Publication

- You start receiving personalized, “encouraging” rejections.

- Agents or editors reject the manuscript you submitted but ask you to send your next work. (They can see that you’re on the verge of producing something great.)

- Your mentor (or published author friend) tells you to contact his agent, without you asking for a referral.

- An agent or editor proactively contacts you because she spotted your quality writing somewhere online or in print.

- You’ve outgrown the people in your critique group and need to find more sophisticated critique partners.

- Looking back, you understand why your work was rejected and can see that it deserved rejection. You probably even feel embarrassed by earlier work.

Time-Waster 5: Focusing on Publishing When You Should Be Writing

Some writers are far too concerned with queries, agents, marketing, or conference going, instead of first producing the best work possible.

Don’t get me wrong—for some types of nonfiction, it’s essential to have a platform in place before you write the book. The fact that nonfiction authors don’t typically write the full manuscript until after acceptance of their proposal (with the exception of memoir and creative nonfiction) is indicative of how much platform means to their publication.

But for everyone else (those of us who are not selling a book based solely on the proposal); It's best not to get consumed with finding an agent until you’re a writer ready for publication.

And now we come to that tricky matter again. How do you know it’s that time? Let’s dig a little deeper.

EVALUATING YOUR PLACE ON THE PUBLICATION PATH

Whenever I sit down for a critique session with a writer, I ask three questions early on: How long have you been working on this manuscript, and who has seen it? Is this the first manuscript you’ve ever completed? And finally: How long have you been actively writing?

These questions help me evaluate where the writer might be on the publication path. Here are a few generalizations I can often make:

- Most first manuscript attempts are not publishable, even after revision, yet they are necessary and vital for a writer’s growth. A writer who’s just finished her first manuscript probably doesn’t realize this and will likely take the rejection process very hard. Some writers can’t move past this rejection. You’ve probably heard experts advise that you should always start working on the next manuscript rather than wait to publish the first. That’s because you need to move on and not get stuck on publishing your first attempt.

- A writer who has been working on the same manuscript for years and years—and has written nothing else—might have a motivation problem. There isn’t usually much valuable learning going on when someone tinkers with the same pages over a decade.

- Writers who have been actively writing for many years, have produced multiple full-length manuscripts, and have one or two trusted critique partners (or mentors) are often well positioned for publication. They probably know their strengths and weaknesses, and have a structured revision process. Many such people require only luck to meet preparedness.

- Writers who have extensive experience in one medium and then attempt to tackle another (e.g., journalists tackling the novel) may overestimate their abilities to produce a publishable manuscript on the first try. That doesn’t mean their effort won’t be good, but it might not be good enough. Fortunately, any writer with professional experience will probably approach the process with a professional mind-set, a good network of contacts to help him understand next steps, and a range of tools to overcome the challenges.

Notice I have not mentioned talent. I have not mentioned creative writing classes or degrees. I have not mentioned online presence. These factors are usually less relevant in determining how close you are to publishing a book-length work.

The two things that are relevant:

1. How much time you’ve put into writing. I agree with Malcolm Gladwell’s ten-thousand-hour rule in Outliers: The key to success in any field is, to a large extent, a matter of practicing a specific task for a total of around ten thousand hours.

2. Whether you’re reading enough to understand where you are on the spectrum of quality. In his series on storytelling (available on YouTube), Ira Glass says:

The first couple years that you’re making stuff, what you’re making isn’t so good. It’s not that great. It’s trying to be good, it has ambitions, but it’s not that good. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, your taste is still killer. Your taste is good enough that you can tell that what you’re making is kind of a disappointment to you. You can tell that it’s still sort of crappy. A lot of people never get past that phase. A lot of people at that point quit. … Most everybody I know who does interesting creative work, they went through a phase of years where they had really good taste [and] they could tell that what they were making wasn’t as good as they wanted it to be.

If you can’t perceive the gap—or if you haven’t gone through the “phase”—you probably aren’t reading enough. How do you develop good taste? You read. How do you understand what quality work is? You read. What’s the best way to improve your skills aside from writing more? You read. You write, and you read, and you begin to close the gap between the quality you want to achieve, and the quality you can achieve.

In short: You’ve got to produce a lot of crap before you can produce something publishable.

KNOWING WHEN IT’S TIME TO CHANGE COURSE

I used to believe that great work would eventually get noticed—you know, that old theory that quality bubbles to the top?

I don’t believe that any more.

Great work is overlooked every day, for a million reasons. Business concerns outweigh artistic concerns. Some people are just perpetually unlucky.

To avoid beating your head against the wall, here are some questions that can help you understand when and how to change course.

1. Is your work commercially viable? Indicators will eventually surface if your work isn’t suited for commercial publication. You’ll hear things like: “Your work is too quirky or eccentric.” “It has narrow appeal.” “It’s experimental.” “It doesn’t fit the model.” Or possibly, “It’s too intellectual, too demanding.” These are signs that you may need to consider self-publishing—which will also require you to find the niche audience you appeal to.

2. Are readers responding to something you didn’t expect? I see this happen all the time: A writer is working on a manuscript that no one seems interested in but has fabulous success on some side project. Perhaps you really want to push your memoir, but everyone loves the humorous tip series on your blog. Sometimes it’s better to pursue what’s working, and what people express interest in, especially if you take enjoyment in it. Use it as a stepping-stone to other things, if necessary.

3. Are you getting bitter? You can’t play poor, victimized writer and expect to get published. As it is in romantic relationships, pursuing an agent or editor with an air of desperation, or with an Eeyore complex, will not endear you to them. Embittered writers carry a huge sign with them that screams, “I’m unhappy, and I’m going to make you unhappy, too.”

If you find yourself demonizing people in the publishing industry, taking rejections very personally, feeling as if you’re owed something, and/or complaining whenever you get together with other writers, it’s time to find the refresh button. Return to what made you feel joy and excitement about writing in the first place. Perhaps you’ve been focusing too much on getting published, and you’ve forgotten to cherish the other aspects. Which brings me to the overall theory of how you should, at various stages of your career, revisit and revise your publication strategy.

REVISING YOUR PUBLISHING PLAN

No matter how the publishing world changes, consider these three timeless factors as you make decisions about your next steps forward.

1. What makes you happy: This is the reason you got into writing in the first place. Even if you put this on the back burner in order to advance other aspects of your writing and publishing career, don’t leave it out of the equation for very long. Otherwise your efforts can come off as mechanistic or uninspired, and you’ll eventually burn out.

2. What earns you money: Not everyone cares about earning money from writing—and I believe that anyone in it for the coin should find some other field—but as you gain experience, the choices you make in this regard become more important. The more professional you become, the more you have to pay attention to what brings the most return on your investment of time and energy.

3. What reaches readers or grows your audience: Growing readership is just as valuable as earning money. It’s like putting a bit of money in the bank and making an investment that pays off as time passes. Sometimes you’ll want to make trade-offs that involve earning less money in order to grow readership, because it invests in your future. (E.g., for a time you might focus on building a blog or a site, rather than writing for print publication, to grow a more direct line to your fans.)

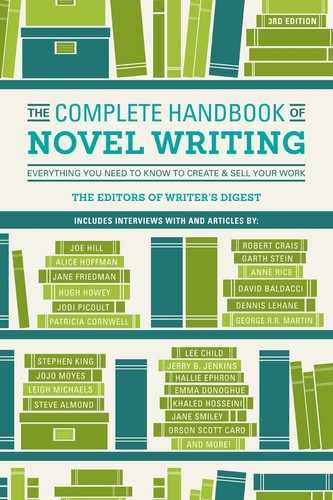

[INSERT IMAGE_makesyouhappy.tiff]

It is rare that every piece of writing you do, or every opportunity presented, can involve all three elements at once. Commonly you can get two of the three. Sometimes you’ll pursue certain projects with only one of these factors in play. You get to decide based on your priorities at any given point in time.

At the very beginning of this chapter, I suggested that it might be nice if someone could tell us if we’re wasting our time trying to get published.

Here’s a little piece of hope: If your immediate thought was, I couldn’t stop writing even if someone told me to give up, then you’re much closer to publication than someone who is easily discouraged. The battle is far more psychological than you might think. Those who can’t be dissuaded are more likely to reach their goals, regardless of the path they ultimately choose.