Diagnosing Hypothyroidism

![]()

In This Chapter

- Critical blood tests for hypothyroidism

- Other tests you may need

- Obtaining and interpreting your test results

- Why you can’t always trust lab ranges

If you’re experiencing one or more of the symptoms described in Chapter 6 and believe the cause might be hypothyroidism, you shouldn’t hesitate to see a doctor and get tested. The initial phase of this process is straightforward—your doctor takes some of your blood, and then sends it to a lab with instructions on which tests to run. What makes things complicated is that many doctors fail to ask for the right combination of tests; and many doctors also fail to correctly interpret the results.

This chapter guides you through the hypothyroidism testing and analysis process. It tells you the best methods for diagnosing your condition, and explains the most common ways in which doctors get important details wrong.

Some physicians dislike patients learning about diagnostic procedures, claiming “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.” But when it comes to hypothyroidism, it’s much more dangerous to be uninformed. After reading this chapter you’ll know what errors to keep an eye out for, and how to ensure you’re receiving the most accurate diagnosis possible.

Key Blood Tests for Hypothyroidism

The perfect way to detect thyroid disease would be to measure how T3 is affecting the energy levels of your cells’ “batteries,” called mitochondria. If your mitochondria turned out to be low on power, that would be definitive proof you’re hypothyroid.

Unfortunately, medical science currently can’t check your energy at the cellular level. So instead of one straightforward test, a doctor who’s a thyroid expert will order four indirect tests: TSH, free T4, free T3, and thyroid antibodies. No one of these tests tells the whole story. But if a doctor is experienced at analyzing the results from all of these tests combined—while at the same time paying attention to your symptoms—the chances are great that she’ll be able to judge both whether you’re hypothyroid and what sort of treatment you need.

Thyroidian Tip

If you’re already on thyroid medication, or if you’re taking some other medication, schedule your doctor’s appointment for the morning and delay taking your pills until after your blood’s been extracted. This will decrease the chances of medication skewing your test results.

TSH

Your thyroid increases and decreases its hormone production based on the orders it receives from a small organ just above your sinuses called the pituitary gland. When your body is low on energy, your pituitary gland responds by making thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). As its name indicates, TSH stimulates your thyroid, effectively telling it “We need more power. Get to work and produce more hormones.”

Labs can detect the level of TSH in your bloodstream. When your TSH is above normal, it means you have too small an amount of thyroid hormones, and in response your pituitary gland is releasing more TSH than usual to tell your thyroid to step up production. Conversely, if your TSH is below normal, it means you have too great an amount of thyroid hormones, and in response your pituitary gland is releasing less TSH than usual to slow your thyroid’s production. In other words, there’s an inverse relationship between your TSH and thyroid hormone levels because your pituitary gland is continually trying to address any imbalance.

At first blush, it might seem that the TSH test will tell you everything you need to know. In fact, many doctors mistakenly order this test exclusively to check on your thyroid. But relying on the TSH alone is a serious mistake.

First, the TSH level in your bloodstream isn’t a snapshot of your current condition. Instead, it represents a 2-3 month average of your pituitary gland’s activities. That’s good in that it provides a long-term look at your body. However, it means you can experience hypothyroid symptoms for 2-3 months before your condition is reflected by the TSH test. This can lead to a doctor pronouncing “you’re normal” when you’re really in the early stages of hypothyroidism.

Further, if you have Hashimoto’s disease, you might swing back and forth between hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, a condition called Hashitoxicosis. Because the TSH is a long-term average, the two extremes can cancel each other out, resulting in a TSH level that’s normal … and that’s masking the war occurring between your immune system and your thyroid.

In addition, the TSH level doesn’t reflect whether your thyroid hormones are successfully energizing your cells. For example, if you have plenty of T4 but it’s not being converted to T3 (see Chapter 1), or if your T3 can’t penetrate your cells (see Chapter 14), your TSH level will be normal but you’ll actually be hypothyroid.

Then again, you could have a healthy thyroid but an ailing pituitary gland. For example, if your pituitary is underactive, it’ll cause your thyroid to underproduce hormones; but the low TSH level will make your doctor think that you have the opposite problem and are hyperthyroid.

So while the TSH test is a very useful tool, it’s not enough by itself to evaluate your status.

Crash Glanding

You may hear advocates of old-school thyroid methods claim the TSH test is inaccurate. It’s true that a doctor relying on the TSH test alone will reach incorrect conclusions for a substantial number of patients. But all this means is your doctor should run a TSH test in conjunction with other key thyroid tests—and while carefully taking into account your symptoms—to paint a complete picture. To abandon TSH testing as old-school disciples recommend would be throwing away one of the most helpful diagnostic tools available for your health.

As explained in Chapter 1, roughly 85-90 percent of the hormones made by your thyroid are T4. T4 is a “storage” hormone designed to circulate in your bloodstream, and be stored in your tissues, until thyroid hormone is needed by a particular area of your body. When energy is called for, your body converts T4 to T3. And it’s T3 that actually does the work of powering up the mitochondria in your cells.

Labs can easily measure the amount of T4 in your bloodstream that’s available for conversion, called free T4; and also the amount of circulating T3 that’s available for immediate use, called free T3.

And unlike the TSH test which reflects a 2-3 month average, the free T4 and free T3 tests reflect the activities of those hormones within the past 7-14 days. These tests therefore offer a more immediate picture of what’s happening in your body.

Crash Glanding

Your body renders over 96 percent of T3 and over 99 percent of T4 molecules inert by binding them with proteins. (No one knows why, though some speculate it’s a way of preserving iodine beyond what can be stored in the thyroid.) However, it’s only the unbound, or free, hormones that have any effect on your health. Free T4 and free T3 can’t be accurately calculated from total T4/T3, because there are a variety of factors that can affect the totals (ranging from pregnancy to how much protein you’ve recently eaten) but have zero impact on the free hormones. So be wary of any doctor who runs old-fashioned total T4/T3 tests instead of modern free T4/T3 tests.

Evaluating your TSH level in conjunction with free T4 and free T3 levels provides a much clearer view than can be gotten from considering TSH alone. For example, if you’re in the early stages of hypothyroidism, the 2-3 month average represented by your TSH level might not reflect the recent changes in your body; but the more “in the moment” free T4/T3 numbers will show up as low, alerting your doctor to the problem. Catching hypothyroidism early gives you the opportunity to improve your diet, cut down on toxins (see Chapters 18 and 22), and start right away on thyroid medication, which could end up mitigating the severity of the disease; and will definitely make you feel better by eliminating your symptoms.

As another example, if your pituitary gland is underactive, your TSH level will be low, making you appear hyperthyroid. If your free T4/T3 is also low, however, an experienced thyroid doctor will know to suspect a pituitary problem and prescribe an ultrasound or MRI to take a close look at that gland.

Then again, your body might be having trouble converting T4 into T3. A frequent cause of this is a lack of selenium, which can be cured by simply eating a Brazil nut a day. If conversion is the issue, your TSH and your free T4 levels will both be normal, but your free T3 level will be low.

The latter is a perfect example of why it’s important to test for free T4 and free T3. Many doctors are knowledgeable enough to order TSH and free T4 tests, but then neglect to include the free T3 test. These doctors assume that the free T3 level will merely echo the level of free T4. While they’ll be correct the majority of the time, in my experience 20-30 percent of hypothyroid patients have a discrepancy between their T4 and T3 levels (that is, proportionally higher T4 than T3, indicating conversion problems). If you happen to be one of those patients, you’re at risk of being prescribed the wrong treatment when free T3 testing is skipped.

If your doctor tests your blood for TSH, free T4, and free T3, the results will provide a pretty good view of your thyroid’s status. However, there’s one other test category needed to complete the picture.

Antibodies

As mentioned previously, the early stages of Hashimoto’s disease—which is the cause of roughly 75-85 percent of hypothyroidism cases—can create a condition of Hashitoxicosis in which you’re swinging between too little and too much thyroid hormones. The two extremes can cancel each other out, resulting in a TSH level that appears normal. At the same time, your free T4/T3 levels will depend on the state of your Hashitoxicosis over the week before you happen to have your blood taken. In other words, they might be low, or high, or even normal, depending on what stage of the pendulum swing the disease is in.

Therefore, when you’re first being diagnosed, the only way to be certain whether or not you have a thyroid autoimmune disease such as Hashimoto’s is to test for thyroid antibodies. More specifically, your doctor should test for thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies and thyroglobulin (Tg) antibodies. If you have Hashimoto’s, the chances are enormous that you’ll have high levels of one or both of these antibodies.

Other Testing

Even if your symptoms point strongly to hypothyroidism, you shouldn’t hesitate to allow your doctor to test for other causes. It’s possible some other disease is actually responsible. And it’s just as possible that you’re hypothyroid and have another condition occurring at the same time, making your life doubly difficult (as described in Chapter 6).

In addition, you may require examination that goes beyond blood tests. For exam-ple, if your doctor suspects you have Hashimoto’s disease, he might prescribe an ultrasound to check for evidence of cellular destruction. Alternatively, if during your physical exam your doctor notices a growth on your thyroid, you may require ultrasound testing, and possibly a biopsy, to determine whether the growth is dangerous (see Chapter 13).

No matter what the results from the lab are, always pay attention to your symptoms. If your body is sending you messages and your test results don’t reflect them, then the problem is usually with the testing, not with what you’re feeling.

Analyzing Your Test Results

A few days after your doctor sends your blood to a lab, the test results—which are usually a small collection of numbers fitting onto a single sheet of paper—will be faxed to her office. As explained in Chapter 4, you can request your doctor’s office to fax that same sheet of paper to you. You can then study the results at your leisure before the next visit to your doctor. This will allow you to know what to expect, and to prepare any pertinent questions.

Alternatively, you can request a photocopy of the results after meeting with your doctor. This will give you the opportunity to study the data and more clearly understand how your doctor arrived at her diagnosis.

Each of your tests will result in a single number that’s judged by where it falls within the range considered normal for that particular test. The key thyroid tests and their ranges are as follows:

Key Tests and Ranges for Hypothyroidism

| Test name | Typical lab range | Optimal range |

| TSH | 0.4-4.5 mIU/L | 0.3-2.0 mIU/L |

| Free T4 | 0.8-1.8 ng/dL | 1.1-1.8 ng/dL |

| Free T3 | 230-420 pg/dL | same as lab |

| Thyroid Peroxidase | ||

| (TPO) Antibodies | <35 IU/mL | same as lab |

| Thyroglobulin | ||

| (Tg) Antibodies | <20 IU/mL | same as lab |

Interpreting results using these ranges is mostly straightforward. For example, if your free T3 level is 300 pg/dL (picograms per deciliter of blood), then it’s normal because it falls within the range of 230-420 pg/dL. Alternatively, if your T3 level is 50 pg/dL, then it’s much too low and you’re probably hypothyroid.

Similarly, if either of your antibody counts is 900 IU/mL (international unit for antibodies per milliliter of blood), then you’re way over the normal limit—35 for TPO and 20 for Tg—and probably have an autoimmune disease such as Hashimoto’s.

More complicated are TSH and free T4, in which there’s a discrepancy between the lab’s recommended range and what thyroid experts believe is the actual range for good health. If your results happen to fall into the gray area between these two ranges, then the next section is of vital importance to you.

Why “Normal” Results Might Be Wrong

This chapter previously described how your doctor might pronounce you healthy if he relied on too few blood tests (such as TSH alone, or TSH and free T4 alone). But your doctor might also misdiagnose you as being fine because your results are all in the “normal” range. It’s not that the test results are wrong. Labs usually provide highly accurate measurements. The problem is with the ranges used by the labs for what’s considered “normal.” For TSH, most labs use a broad range of 0.4-4.5 mIU/L (milli-international units per liter of blood). Some labs use an even higher upper limit than 4.5 mIU/L, such as 5.0, 5.5, or a jaw-dropping 6.0.

These ranges were created by averaging the results of numerous people who’ve been tested. That’s a technique that often works; but for reasons that are still being debated, it doesn’t work for the TSH test. Based on real-world experience, most thyroid experts consider the real range for TSH to be much narrower.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) recommends using a TSH range of 0.3-3.0 mIU/L. And based on my own clinical experience with tens of thousands of thyroid patients, I use an even narrower range of 0.3-2.0 mIU/L. Studies have shown this is the range that results when testing only people who have no thyroid disease (as opposed to lab averages mostly comprised of patients with hypothyroid symptoms). Why shouldn’t you be compared to the healthy?

There’s a similar, although less extreme, situation for free T4. Most labs use a range of 0.8-1.8 ng/dL (nanograms per deciliter of blood). In my experience, more accurate is the narrower range of 1.1-1.8 ng/dL.

In other words, if a patient with pertinent symptoms has a TSH level a bit above 2.0 mIU/L, and it’s coupled with a free T4 level a bit below 1.1 ng/dL, I’ll treat that patient for mild hypothyroidism. In the vast majority of cases, the patient will improve within a few weeks of being on thyroid medication. Unfortunately, this scenario is more the exception than the rule. When a lab puts a test result in the “normal” column, most busy doctors will simply accept it, favoring hard numbers over a patient’s symptoms.

It’s been estimated that tens of millions of people are unknowingly suffering from hypothyroidism. It’s bad enough that many of them don’t understand the disease sufficiently to identify its symptoms; and worse that many of the ones who seek help are let down by doctors who also fail to recognize hypothyroidism symptoms. But it’s downright tragic when a patient suspects hypothyroidism, sees a doctor to get tested for it … and is told she’s “normal” because her TSH level isn’t above the lab’s excessive upper range.

Thyroidian Tip

Labs lay out their reports by setting results deemed ordinary in plain type, and the results considered to be unusual in boldface or gray highlights. This draws a busy doctor’s eye away from anything designated In Range. Doctors joke that WNL, or Within Normal Limits, really stands for We Never Looked. But it’s a genuinely serious problem if a lab’s use of a too-broad range causes your hypothyroidism to be ignored.

Don’t let this happen to you. If your test results happen to fall into the gray area between lab ranges and what thyroid experts know to be a more accurate range, discuss the AACE’s recommended range of 0.3-3.0 mIU/L—and this book’s recommended upper limit of 2.0—with your doctor. If your symptoms persist, and your doctor refuses to treat you with thyroid medication, then use Chapter 4 and Appendix B to find a different doctor.

Analyzing Patient Test Results

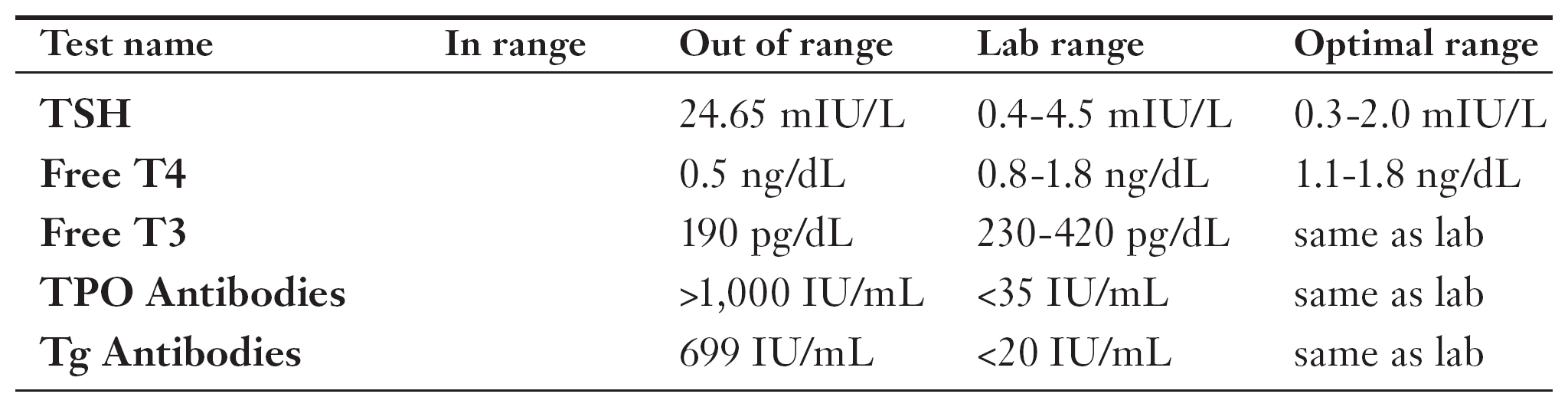

Understanding how to analyze your own test results can be easier after examining real-life examples. The following are true stories of people who were tested for hypothyroidism and, thanks to their being given the right combination of tests and the right interpretation of the results, were successfully diagnosed and treated.

For each patient, you’ll see the test results first. Try to analyze the numbers, and then read the patient’s tale to find out if you’ve interpreted them correctly.

Memory Problems

Dora came to see me when she was about to flunk out of nursing school. Dora never had academic problems before, but suddenly was finding it impossible to remember what she was reading. She asked if I could recommend any natural memory enhancers. I told her there were lifestyle changes and supplements that could help, but first we should conduct a few simple tests to make sure there were no medical causes for these “out of the blue” symptoms. Dora was skeptical, but agreed to humor me.

I doubted the issue was thyroid disease since Dora’s only symptom was poor memory, but I included thyroid tests to be thorough. As you can see from Dora’s results, both her free T4 and free T3 were well below their optimal ranges; and her TSH and antibody counts were through the roof. It was a classic advanced case of Hashimoto’s disease.

After seeing these numbers I was certain Dora’s memory problems would disappear once she was on thyroid medication. However, I warned her it could be several months until the mental damage was fully repaired. Happily, Dora’s usual excellent memory returned in only several weeks, and she ended up doing well in all her classes.

Quest for Growth

Bob came to me feeling weak, tired, and with a poor libido. A friend of his was taking growth hormone replacement therapy and feeling great, and Bob believed he needed the same thing. “It’s not the right treatment for most adults,” I told him, “but let’s do some tests before making any conclusions.” The results showed Bob to be hypothyroid via his low levels of free T4 and T3, and a high TSH of 11. Ironically, other tests showed Bob’s growth hormone level was too high as well! When the pituitary gland makes an excessive amount of TSH, it can accidentally release too much growth hormone at the same time. Thyroid medication soon solved all of these problems.

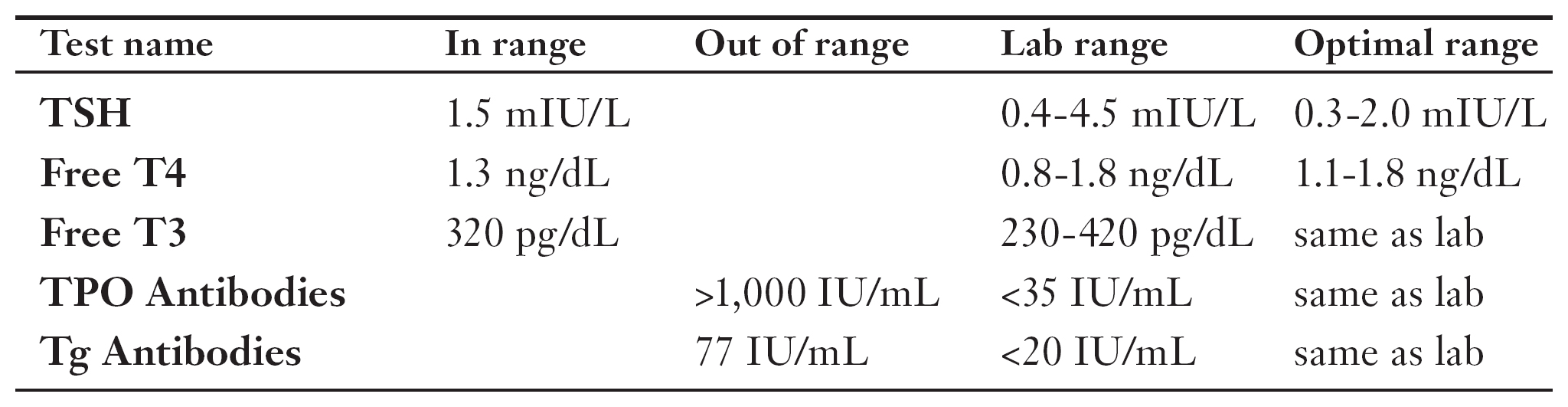

Melody couldn’t quite put her finger on it, but she hadn’t been feeling “right” for the past six months. She was convinced there was some sort of problem with her body. The final straw was her weight slowly creeping up, even though she was a college student majoring in exercise physiology. In addition, she was feeling anxious for no apparent reason. Melody’s family doctor had run some basic blood tests—including ones for TSH and free T4—and then told her she was fine. Not believing him, she came to see me.

Medical schools have a tradition of teaching that patients aren’t great judges of their health. However, I’ve learned that most people actually have a pretty good sense of what’s going on with their bodies. I ordered a more thorough battery of tests for Melody, including those for antibodies. It turned out her thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies were through the roof, and her thyroglobulin (Tg) antibody count was high, too.

Melody’s TSH, free T4, and free T3 were all normal. However, the antibodies indicated major trouble was coming unless something was done. I prescribed a very low daily dose of desiccated thyroid, which helped bind up the antibodies and reduce their harmful effects. (If Melody were not already living a healthy lifestyle, I would’ve additionally suggested the dietary and toxin avoidance advice given in Chapters 18 and 22.) Over the next few months Melody’s antibody levels substantially decreased. She also lost the extra weight, and her anxiety disappeared.

Joan was a 43-year-old mother with a full life who began feeling sad for no apparent reason. Soon after that Joan became exhausted performing everyday chores that normally gave her no trouble. Joan’s PMS, which was usually mild, grew severe. She noticed her hair was thinning, and she was gaining weight.

Joan went to see her family doctor, who ran TSH and free T4 tests. As you can see, the results were in the lab’s “normal” range. Her doctor therefore dismissed Joan’s suspicion of thyroid disease and prescribed antidepressants.

Joan felt sure she had a physical problem, so she went to see a different doctor; and then a third doctor. They all told her the same thing: her tests results were “normal.”

After Joan gained 30 pounds, a friend of hers recommended me. It took only seconds of looking at her test results to realize Joan was unlucky enough to be in the “gray area” that’s within a too-broad lab range but actually outside the optimal range for health.

I told Joan her symptoms were classic for hypothyroidism, and her TSH and free T4 levels indicated she was in the early stages of the disease. After giving Joan a more complete set of tests—which included antibody testing that showed she had Hashimoto’s—I put her on thyroid medication. After several months, all of Joan’s symptoms disappeared. Joan then focused on losing the weight she’d gained while doctors were telling her she was fine.

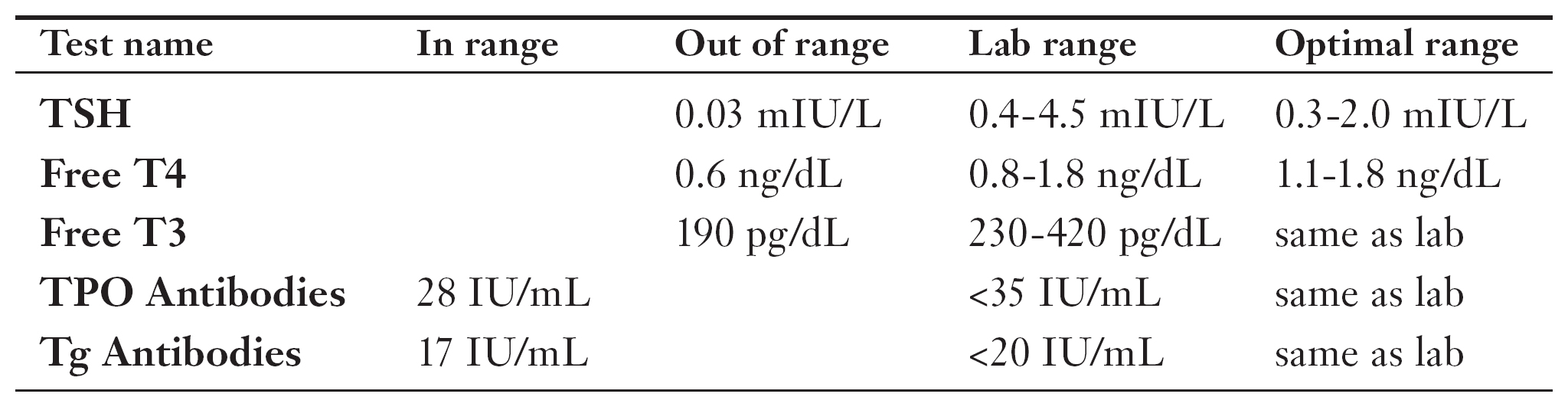

Headaches and Back Pain

Tara had an unusual set of symptoms for a young woman: continual severe headaches, debilitating back pain, and painful irritable bowel syndrome. She’d already been tested by an internist, a neurologist, a gastroenterologist, and a rheumatologist, but none of them had provided a credible diagnosis or effective treatment. I looked over all her previous tests and saw she’d never been checked for thyroid disease. I therefore ordered basic thyroid testing, along with detailed tests of her bowel function and an MRI of her back.

As you can see, Tara’s TSH level was quite low, which by itself is a sign of hyperthyroidism. However, her free T4 and free T3 levels were also low, which indicated her thyroid gland was underperforming because it was being told to by her pituitary gland. Tara’s previous doctors had given her a brain MRI, but it didn’t provide a good view of her pituitary. I ordered a new MRI that did … and discovered a growth putting so much pressure on her pituitary gland that it prevented full production of TSH and other pituitary hormones.

A pituitary growth that’s benign will usually make the same hormones as the gland, leading to excessive TSH. Since that wasn’t happening, I suspected cancer. I recommended prompt surgery to remove and identify the growth. The operation went smoothly—and we were all happy to discover the growth actually was benign. Tara’s pituitary gland and thyroid quickly returned to normal, so she required no medication; and over the next several months her full health was restored.

The Least You Need to Know

- Your initial hypothyroid testing should consist of TSH, free T4, free T3, and antibody blood tests.

- If you’re on medication, get your blood drawn in the morning and then take your pills afterward.

- Have your doctor’s office fax over your test results and then use this chapter to analyze them before your next visit.

- If your test results are within a lab’s range but outside the optimal range and you still have symptoms, don’t let your doctor convince you that you’re okay; seek treatment.