Diagnosing Hyperthyroidism

![]()

In This Chapter

- Conditions with similar or parallel symptoms

- Critical blood tests for hyperthyroidism

- Other tests you may need

- Obtaining and interpreting your test results

If you’re experiencing one or more of the symptoms described in Chapter 10 and believe the cause might be hyperthyroidism, you shouldn’t hesitate to see a doctor and get tested.

The initial phase of this process is straightforward—your doctor takes some of your blood, and then sends it to a lab with instructions on which tests to run. What makes things a bit complicated is that many doctors fail to ask for the right combination of tests. In addition, some doctors fail to sufficiently consider all possible causes.

This chapter guides you through the hyperthyroidism diagnostic process. It first discusses conditions that resemble hyperthyroidism and might account for your symptoms. It then details the best testing and analysis methods for determining whether you’re hyperthyroid.

After reading this chapter you’ll know what errors to keep an eye out for, and how to ensure you’re receiving the most accurate diagnosis possible.

Similar and Overlapping Conditions

If you’re experiencing hyperthyroidism symptoms, you should definitely get thyroid blood tests. However, that doesn’t mean you should skip other types of testing. There are conditions that cause many of the same symptoms as hypothyroidism, and it’s possible that your problems are stemming from one of them. Further, it’s possible that you’re suffering from hyperthyroidism and some other condition simultaneously. Certain conditions not only resemble but frequently coexist with hyperthyroidism, making normally unpleasant symptoms even worse.

The next six sections therefore briefly describe common conditions that produce many of the same symptoms as hyperthyroidism. If you find one or more of these conditions fits closely with the problems you’ve having, don’t hesitate to bring it up when you speak with your doctor. Take care to clearly explain which symptoms make you suspicious—your doctor will be more interested in what you’re feeling and experiencing so he can make his own diagnosis—and then ask if he believes it makes sense to test for some other specific condition in addition to your thyroid testing.

Further, once your illness has been diagnosed, don’t stop there; discuss with your doctor whether there are any aspects of your diet, environment, and lifestyle that might have contributed to its development. Dealing with not only your symptoms but the underlying causes vastly increases your chances of achieving optimum health.

Autoimmune Diseases

Graves’ is by no means the only common autoimmune disease. Others range from rheumatoid arthritis to lupus to type 1 diabetes. And especially in the early stages, many autoimmune disorders produce the same symptoms, including anxiety and weight loss. So even if you have autoimmune disease, it isn’t necessarily Graves’.

Then again, if you do have Graves’, that doesn’t mean you don’t also have other autoimmune diseases. Once your body demonstrates a tendency to attack itself in one area, there’s a greater chance it’ll do so in other areas. It’s therefore wise to get tested annually for other autoimmune disorders.

Anxiety

Clinical anxiety is a disorder stemming from problems with brain chemistry. It typically causes many of the same symptoms as hyperthyroidism, including the feeling of being anxious, a rapidly pounding heart, shakiness and tremors, weight loss, insomnia, heated skin, and numbness or tingling in hands and feet.

To discover whether your anxiety originates from your brain or your thyroid, simply have your doctor run thyroid blood tests. If you turn out to have clinical anxiety, it’s very treatable via medication and talk therapy. Conversely, if you’re hyperthyroid, treatment will make your anxiety fade away … along with symptoms you may not even realize you had until you suddenly feel healthy again.

Irregular Heartbeat

There’s a feedback link between your brain and your heart. For example, if you see something threatening, your brain will make your heart beat faster to prepare you for either running or fighting.

What you may not know is that the link goes both ways. If your heart starts beating in an irregular manner, chemicals in your brain will respond by making you feel anxious. Further, in a vicious cycle, your brain will then respond by making your heart beat even faster and you’ll end up with all the symptoms associated with anxiety.

This condition can occur due to atrial fibrillation, in which your heart’s two upper chambers fall out of sync with its two lower chambers, and beat too quickly and erratically. It can also occur due to mitral valve prolapse, in which the valve between your left upper chamber and lower chamber doesn’t close properly, leading to your heart racing.

If you have such a problem, your doctor may be able to identify it by simply listening to your heart or performing an electrocardiogram (ECG) test in his office. If the problem comes and goes, however, or is a mild case, monitoring for 24 hours or more by experienced cardiologists might be required to spot it.

Adrenal Overactivity

If you have a condition that causes your adrenal glands to produce too much cortisol, such as Cushing’s syndrome or pheochromocytoma, you can experience many of the symptoms of hyperthyroidism, including a rapidly pounding heart, anxiety, shakiness and tremors, weight loss, and bone loss.

For detailed information about adrenal diseases, see Chapter 14.

The manic side of bipolar disorder can spawn many hyperthyroid symptoms, including abnormal excess energy, racing mind, poor concentration, irritability, anxiety, insomnia, increased sex drive, and weight loss.

If you’re bipolar, you’re likely to know it; but that doesn’t mean you aren’t also hyperthyroid. You could have both conditions, with the hyperthyroidism making your manic episodes even more extreme than they would be on their own. The best way to be sure is to simply have your doctor run thyroid blood tests.

Stimulants and Medications

You may be consuming a stimulant or medicine without realizing it’s causing hyperthyroidism symptoms. For example, it’s common to do more social coffee drinking as you get older. However, your body’s ability to break down caffeine decreases with age. You may therefore be taking in more caffeine precisely at a time in life when you’re least able to tolerate it. The side effects of caffeine overdosing mimic hyperthyroidism: anxiety, panic attacks, irritability, shakiness, racing thoughts, a rapid heartbeat, and insomnia.

Making matters worse, the insomnia can lead you to drink even more coffee the next day to stay awake—leading to increasingly severe hyperthyroidism-like symptoms.

A similar situation exists for other stimulants, including nicotine, weight loss pills, and—on a more extreme scale—illegal drugs such as cocaine and ecstasy.

Some medications also have side effects resembling hyperthyroidism. These include prescription amphetamines, certain allergy pills and decongestants, certain antidepressants, and attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity (ADHD) suppressors such as Adderall and Ritalin. The side effects can include anxiety, panic attacks, tremors, rapid heartbeat, numbness or tingling in the hands and feet, insomnia, diarrhea, increased sex drive, and weight loss.

If you suspect an optional stimulant may be causing your problems, simply stop consuming it for a month or two and see if the symptoms disappear. Alternatively, if you suspect a necessary medication may be the culprit, discuss with your doctor whether you can either use a substitute with less severe side effects or add in other medications that mitigate the side effects.

Key Blood Tests for Hyperthyroidism

The perfect way to detect thyroid disease would be to measure how T3 is affecting the energy levels of your cells’ mitochondria (see Chapter 1). If your mitochondria turned out to be supercharged beyond healthy limits, that would be definitive proof you’re hyperthyroid.

Unfortunately, medical science currently can’t check your energy at the cellular level. So instead of one straightforward test, a doctor who’s a thyroid expert will order four types of indirect tests: TSH, free T4, free T3, and antibodies.

No one of these tests tells the whole story. But if a doctor is experienced at analyzing the results from all of these tests combined, while at the same time pays attention to your symptoms, the chances are great that he’ll be able to judge both whether you’re hyperthyroid and what sort of treatment you need.

Thyroidian Tip

If you’re already on thyroid medication, or if you’re taking some other medication, schedule your doctor’s appointment for the morning and delay taking your pills until after your blood’s been extracted. This will decrease the chances of medication skewing your test results.

TSH

As explained in Chapter 1, your thyroid increases and decreases its hormone production based on the orders it receives from a small organ just above your sinuses called the pituitary gland. When your body is low on energy, your pituitary gland responds by making thyroid stimulating hormone, or TSH. This stimulates your thyroid to produce its hormones.

Labs can detect the level of TSH in your bloodstream. When your TSH is below normal, it means your body has too much T4 and T3, and in response your pituitary gland is holding back its TSH to tell your thyroid to slow down or stop production.

Conversely, when your TSH is above normal, it means you don’t have enough T4 and T3, and in response your pituitary gland is releasing a large amount of TSH to tell your thyroid to step up production. In other words, there’s an inverse relationship between your TSH and thyroid hormone levels because your pituitary gland is continually trying to address any imbalance.

At first blush, it might seem that the TSH test will tell you everything you need to know. In fact, many doctors mistakenly order this test exclusively to check on your thyroid. But relying on the TSH alone is a serious mistake for several reasons.

First, the TSH level in your bloodstream isn’t a snapshot of your current condition. Instead, it represents a 2-3 month average of your pituitary gland’s activities. That’s good in that it provides a long-term look at your body. However, it means you can experience hyperthyroid symptoms for 2-3 months before your condition is reflected by the TSH test. This can lead to a doctor pronouncing you normal when you’re really in the early stages of hyperthyroidism.

Further, if you have a back-and-forth condition such as Hashitoxicosis (see Chapter 10), you might swing between hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Because the TSH is a long-term average, the two extremes can cancel each other out, resulting in a TSH level that’s normal … and that’s masking the war occurring between your immune system and your thyroid.

In addition, the TSH level doesn’t reflect whether your thyroid hormones are successfully energizing your cells. For example, if you have an excessive amount of T4 but it’s not being converted to T3 (see Chapter 1), or if the T3 can’t penetrate your cells (see Chapter 14), your TSH level will indicate you’re hyperthyroid but you’ll actually be hypothyroid.

Then again, you could have a healthy thyroid but an ailing pituitary gland. For example, if your pituitary has grown a TSH-secreting adenoma (see Chapter 10), it’ll cause your thyroid to overproduce hormones; but the high TSH level will make your doctor think that you have the opposite problem and are hypothyroid.

So while the TSH test is a very useful tool, it’s not enough by itself to evaluate your status.

Free T4 and Free T3

As explained in Chapter 1, roughly 85-90 percent of the hormones made by your thyroid are T4. T4 is a storage hormone designed to circulate in your bloodstream, and be stored in your tissues, until thyroid hormone is needed by a particular area of your body. When energy is called for, your body converts T4 to T3. And it’s T3 that actually does the work of powering up the mitochondria in your cells.

Labs can easily measure the amount of T4 in your bloodstream that’s available for conversion, called free T4; and also the amount of circulating T3 that’s available for immediate use, called free T3.

And unlike the TSH test, which reflects a 2-3 month average, the free T4 and free T3 tests reflect the activities of those hormones within the past 7-14 days. These tests therefore offer a more immediate picture of what’s happening in your body.

Evaluating your TSH level in conjunction with free T4 and free T3 levels provides a much clearer view than can be gotten from considering TSH alone.

For example, if you’re in the early stages of hyperthyroidism, the 2-3 month average represented by your TSH level might not reflect the recent changes in your body, but the free T4/T3 numbers will show up as high, alerting your doctor to the problem. Catching hyperthyroidism early gives you the opportunity to start right away on treatment (see Chapter 12), which is important both in terms of your quality of life (avoiding panic attacks, tremors, etc.) and sparing yourself from the serious damage this disease can cause over time to your heart, bones, and eyes.

As another example, if your pituitary gland is overactive, your TSH level will be high, making you appear hypothyroid. If your free T4/T3 is also high, however, an experienced thyroid doctor will know to suspect a pituitary problem and prescribe an ultrasound or MRI to take a close look at that gland.

If your doctor tests your blood for TSH, free T4, and free T3, the results will provide a pretty good view of your thyroid’s status. However, there’s one other test category needed to complete the picture.

Antibodies

As explained in Chapters 5 and 10, over 80 percent of all thyroid problems are caused by the autoimmune diseases Hashimoto’s (for hypothyroidism) and Graves’ (for hyperthyroidism).

Hashimoto’s occurs when your immune system attacks your thyroid with thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies and/or thyroglobulin (Tg) antibodies. These antibodies can initially swing you back and forth between hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, but ultimately they’ll make you hypothyroid.

Graves’ occurs when your thyroid is attacked with thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin, or TSI. The antibodies TPO and Tg may also be involved; but what really matters is the TSI. That’s because TPO and Tg attack proteins in your thyroid, and their only effect is to destroy the cells. However, TSI binds with the portion of the cells called receptors that receive your pituitary gland’s TSH. Very much like TSH, the TSI stimulates the cells to produce more hormones, and this overproduction is what makes you hyperthyroid.

If your doctor runs tests only for TSH, T4, and T3, she won’t have enough information to determine whether you have Graves’ disease, or Hashimoto’s during a hyperthyroid cycle, or some form of hyperthyroidism that isn’t autoimmune at all; and such information is vital in choosing the best method for treating you.

Alternatively, if you’re in the preliminary stages of Graves’, your TSH, T4, and T3 might all be normal; but TSI testing is likely to turn up the presence of the antibodies, providing you and your doctor with an early warning and the opportunity for preemptive treatment. So when you’re being evaluated for the first time for possible hyperthyroidism, your doctor should include antibody tests for TPO, Tg, and (especially) TSI.

If the lab results show high levels of TPO and/or Tg antibodies alone, you probably have Hashimoto’s and require treatment for hypothyroidism, while if they show high levels of TSI, you have Graves’ and require treatment for that particular form of hyperthyroidism.

Other Testing

As the first section of this chapter indicated, even if your symptoms point strongly to hyperthyroidism, you shouldn’t hesitate to allow your doctor to test for other causes. It’s possible some other disease is actually responsible. And it’s just as possible that you’re hyperthyroid and have another condition occurring at the same time, making your life doubly difficult.

In addition, you may require examination that goes beyond blood tests. For example, if your doctor wants to confirm that you have Graves’ disease, he might request an ultrasound to see whether your thyroid shows signs of enlarging (resulting from TSI overstimulation).

Another common diagnostic tool is an iodine uptake and thyroid scan. For this procedure, your doctor injects you with or has you swallow a tiny amount of radioactive iodine, waits 6-24 hours, and then scans your neck to get a clear picture of what’s going on inside it. If the resulting images show even, diffuse enlargement of your thyroid, you probably have Graves’ disease. If the iodine concentrates in a few areas of your thyroid, that indicates the toxic nodules of Plummer’s disease. Then again, if there are areas of your thyroid that don’t absorb the iodine at all, that’s reason to suspect thyroid cancer, in which case the next step should be a biopsy (see Chapter 13).

No matter what the results from the lab are, always pay attention to your symptoms. If your body is sending you messages and your test results don’t reflect them, then the problem is usually with the testing, not with what you’re feeling.

Analyzing Your Test Results

A few days after your doctor sends your blood to a lab, the test results—which are usually a small collection of numbers fitting onto a single sheet of paper—will be faxed to her office. As explained in Chapter 4, you can request your doctor’s office to fax that same sheet of paper to you. You can then study the results at your leisure before the next visit to your doctor. This will allow you to know what to expect, and to prepare any pertinent questions.

Alternatively, you can request a photocopy of the results after meeting with your doctor. This will give you the opportunity to study the data and more clearly understand how your doctor arrived at her diagnosis.

Crash Glanding

Whenever you receive test results, first check to make sure they include your correct name and birth date. Both labs and doctors’ offices handle thousands of patients, and mistakes happen.

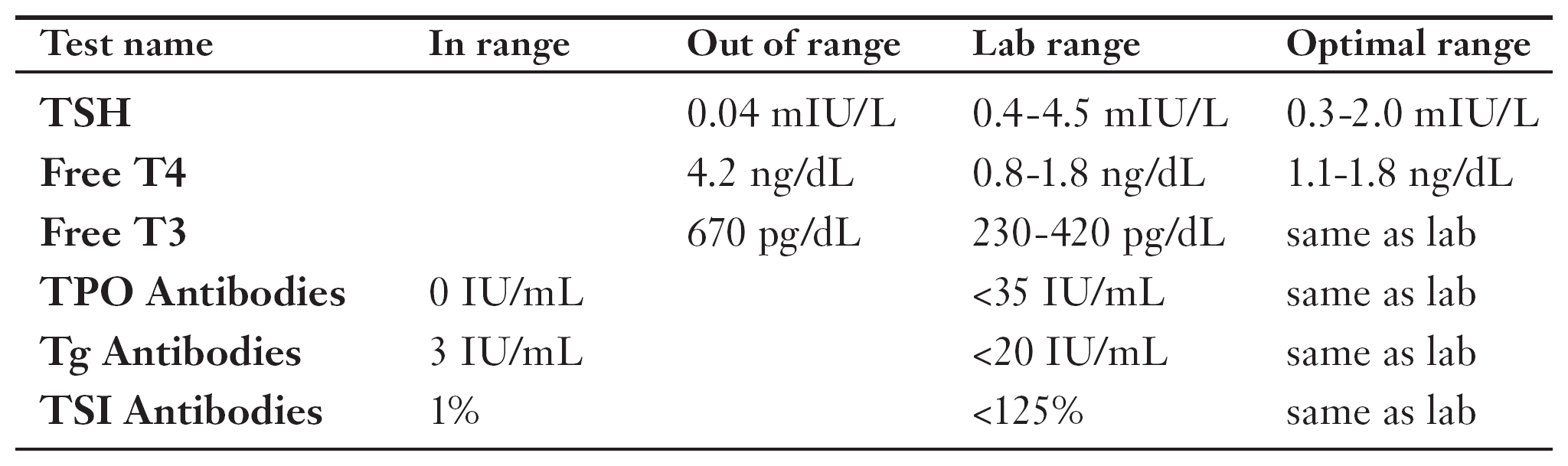

Each of your tests will result in a single number that’s judged by where it falls within the range considered normal for that particular test. The key thyroid tests and their ranges are as follows:

Key Tests and Ranges for Hypothyroidism

| Test name | Typical lab range | Optimal range |

| TSH | 0.4-4.5 mIU/L | 0.3-2.0 mIU/L |

| Free T4 | 0.8-1.8 ng/dL | 1.1-1.8 ng/dL |

| Free T3 | 230-420 pg/dL | same as lab |

| Thyroid Peroxidase | ||

| (TPO) Antibodies | <35 IU/mL | same as lab |

| Thyroglobulin | ||

| (Tg) Antibodies | <20 IU/mL | same as lab |

| TSImmunoglobulin | ||

| (TSI) Antibodies | <125% activity | same as lab |

Interpreting results using these ranges is mostly straightforward. For example, if your free T3 level is 300 pg/dL (picograms per deciliter of blood), then it’s normal because it falls within the range of 230-420 pg/dL. Alternatively, if your T3 level is 700 pg/dL, then it’s much too high and you’re probably hyperthyroid.

Similarly, if your TPO antibody count is 900 IU/mL (international unit for antibodies per milliliter of blood), then you’re way over the normal limit of 35 IU/mL and probably have an autoimmune disease.

A bit more complicated is the range for TSI antibodies. TSI measures how effectively antibodies in your blood bind to cell receptors in the organ of a lab rodent. This is calculated as a percentage, with anything below 125 percent considered as being within normal range.

“Normal” is misleading in this case, though. If you’re at no risk for hyperthyroidism, your TSI score should actually be below 2 percent—that is, at or close to zero. If your level is between 2 percent and 125 percent, it means you might be on the path to Graves’ disease. In this case, it’s wise to start taking preventive measures to keep your TSI low, such as ensuring you’re consuming enough iodine and selenium (see Chapter 1) and are avoiding toxins (see Chapter 22). As long as your TSI level remains below 125 percent, you’re unlikely to develop hyperthyroidism symptoms.

Thyroidian Tip

When the TSI test reports you have antibodies, it’s almost always accurate. When it doesn’t, however, there’s a 10-20 percent chance your thyroid is being attacked by a form of stimulating antibody that this test just doesn’t happen to detect. If your TSI results are under 125 percent but you still suspect you have Graves’, you can ask your doctor to focus on other evidence, including low TSH, high T4 and T3, eye problems, and ultrasound and/or thyroid scan tests that show diffuse enlargement of the thyroid.

One other complication with thyroid lab tests is interpreting TSH and free T4 results, because there’s a discrepancy between the lab’s recommended hypothyroid ranges and what thyroid experts believe is the actual range for good health. If your tests shows you’re hyperthyroid, you don’t have to worry about this. Otherwise, see Chapter 7 for details.

Analyzing Patient Test Results

Understanding how to analyze your own test results can be easier after examining real-life examples. The following are true stories of people who were tested for hyperthyroidism and, thanks to their being given the right combination of tests and the right interpretation of the results, were successfully diagnosed and treated.

For each patient, you’ll see the test results first. Try to analyze the numbers, and then read the patient’s tale to find out if you’ve interpreted them correctly.

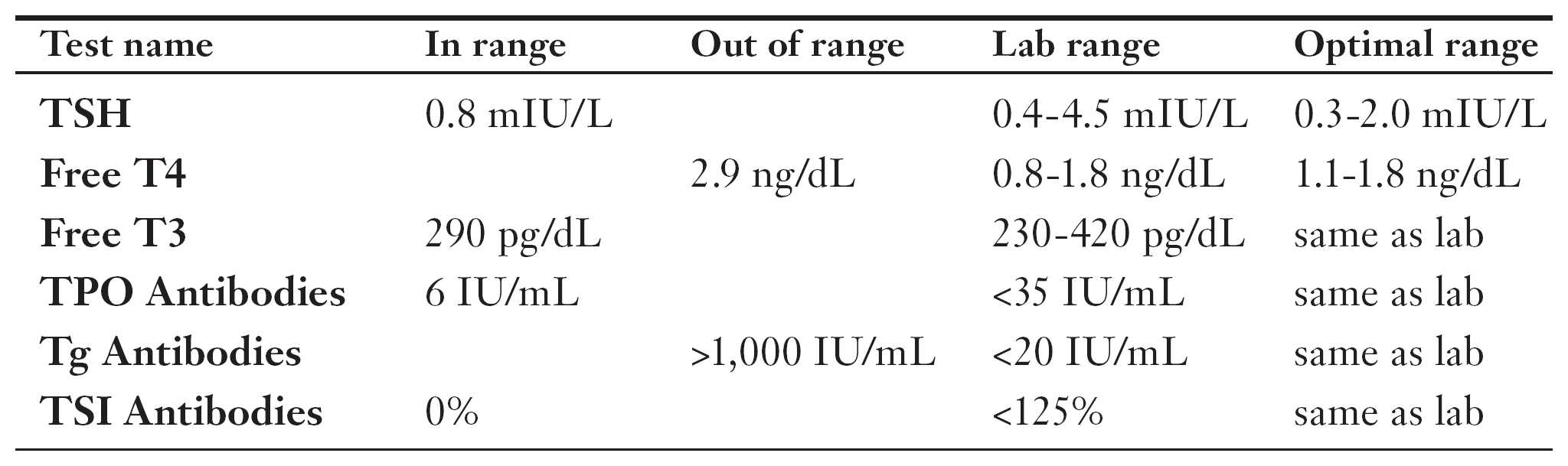

Anxiety

Debbie came to see me in a state of frustration. When she turned 40 a year earlier, she was struck out of the blue with severe anxiety. She’d been to four doctors, and none of them offered a satisfying explanation or successful treatment. Each of them simply indicated she must be “wired” for clinical anxiety. “It’s ridiculous,” Debbie told me. “I’m the most mellow, low-stress person you could imagine.”

As we talked, I learned Debbie’s older sister also developed anxiety after turning 40. Her sister was diagnosed with Graves’ disease, and after it was treated the problem went away.

Each of the previous doctors has tested Debbie’s TSH, found it within the normal range, and dismissed thyroid disease as a possible cause. However, none of them had looked beyond TSH.

I ordered a full range of thyroid blood tests for Debbie. As you can see, her TSH was indeed in the normal range. However, her free T4 was elevated and her Tg antibody count was so high that it was off the charts. That meant Debbie was suffering from an autoimmune thyroid disorder.

Debbie tested negative for TSI, which indicated she didn’t have Graves’ disease. The TSI test can miss antibodies 10-20 percent of the time, but in this case the negative result made sense.

Considering the normal TSH level, I was pretty sure Debbie was suffering from Hashitoxicosis, an early stage of Hashimoto’s disease that swings a patient between hyperthyroid and hypothyroid states. Because the TSH level is a three-month average, the extreme highs and lows tend to cancel each other out, resulting in a TSH that appears normal.

I ordered an ultrasound test to confirm my diagnosis. The images of Debbie’s thyroid showed precisely the damage I expected from Hashitoxicosis.

I treated Debbie for both the hyperthyroid and hypothyroid aspects of her disease, which eased her anxiety. Eventually Debbie’s condition settled into classic hypothyroidism on its own, which was easily treated with thyroid medication.

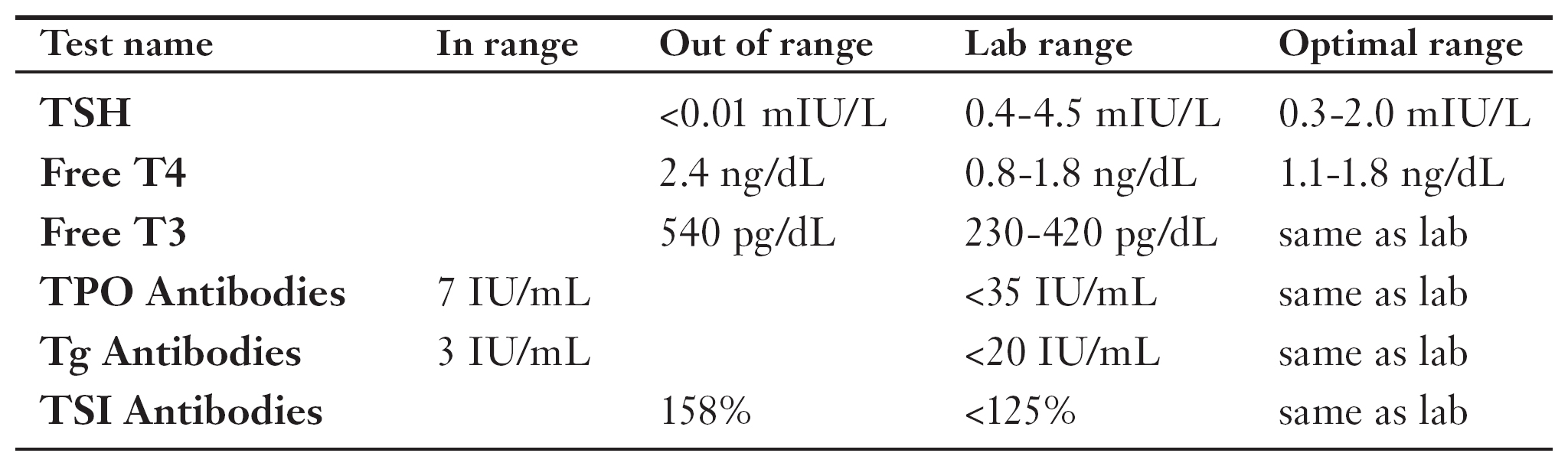

Lump in the Neck

Angie had a clearly visible growth in her neck. “It’s been there a while,” she said. “I didn’t come in sooner because I was terrified it’s cancer. And I still am, but ignoring it hasn’t kept it from growing bigger.” I assured her that a lot of people react the same way, and that I’d do my best for her no matter what it was.

I gave Angie a brief physical exam, and found the lump was on her thyroid. I asked Angie if she’d noticed anything else unusual. “I’m embarrassed to say this,” she replied, “but over the last six months I’ve been sweating like a geyser from my hands, feet, underarms, and the back of my head.” I ran through a symptoms checklist with her, and discovered that she had a strong appetite but was continually losing weight: “My friends say it looks like I’m wasting away. It’s another reason I fear it’s cancer.”

“Angie, does the lump hurt?” I asked. “Sometimes,” she said. “And I’m finding it harder to swallow.”

“That’s actually good news,” I said, “because cancer usually doesn’t hurt. And your collection of symptoms make me suspect another cause. Let’s run some tests.”

As you can see, Angie’s TSH was so low it was off the charts. She also had high levels of T4 and T3, and of TSI antibodies. It was a classic case of Graves’ disease, complete with goiter.

I prescribed 10 mg daily of Tapazole (see Chapter 12) to manage Angie’s hyperthyroidism. That was just enough to make her symptoms tolerable, but not enough to raise her TSH level. Keeping Angie’s TSH low discouraged her thyroid from creating new cells for her goiter. Because the current cells died out without being replaced, the goiter shrank naturally over the next year until its size was insignificant.

Angie and I had to continue keeping her TSH low so the goiter wouldn’t grow back, but after another year on the Tapazole her Graves’ disease petered out, allowing Angie to enjoy normal thyroid function again.

Keeping Her Baby Healthy

Because of its hormonal upheavals, pregnancy is sometimes the trigger for thyroid autoimmune disease. That’s why good obstetricians periodically run blood tests to check for such occurrences. And that’s how Sally discovered, near the end of her first trimester, that her TSH level was an off-the-charts <0.01. This meant her pituitary gland had essentially shut down its TSH production.

Sally’s obstetrician referred her to me. While I examined Sally, we chatted. “I’ve been feeling anxious,” she said, “and my heart has been beating super fast, but this is my first baby. I just assumed it was all part of being pregnant.”

After hearing this, I took Sally’s blood and ordered a full range of thyroid tests. As you can see, Sally turned out to have high levels of T4, T3, and TSI antibodies, which meant she had Graves’ disease. I followed up with an ultrasound, which confirmed the diagnosis via images of an enlarged thyroid.

I explained to Sally that treatment was especially important in her case because Graves’ posed a risk for a miscarriage, birth defects, and heart damage. There was also a risk of the disease spreading to her baby unless we got it under control.

I put Sally on a 2-month starting dose of PTU (see Chapter 12). This lowered Sally’s T4 and T3 into the normal range, but her TSI remained at 180 percent. I countered with a gentle increase in the PTU dosage. I was relieved six weeks later when Sally’s TSI came down to 75 percent. I kept Sally at the same dosage for the remainder of her pregnancy. She had a beautiful baby boy, with no complications.

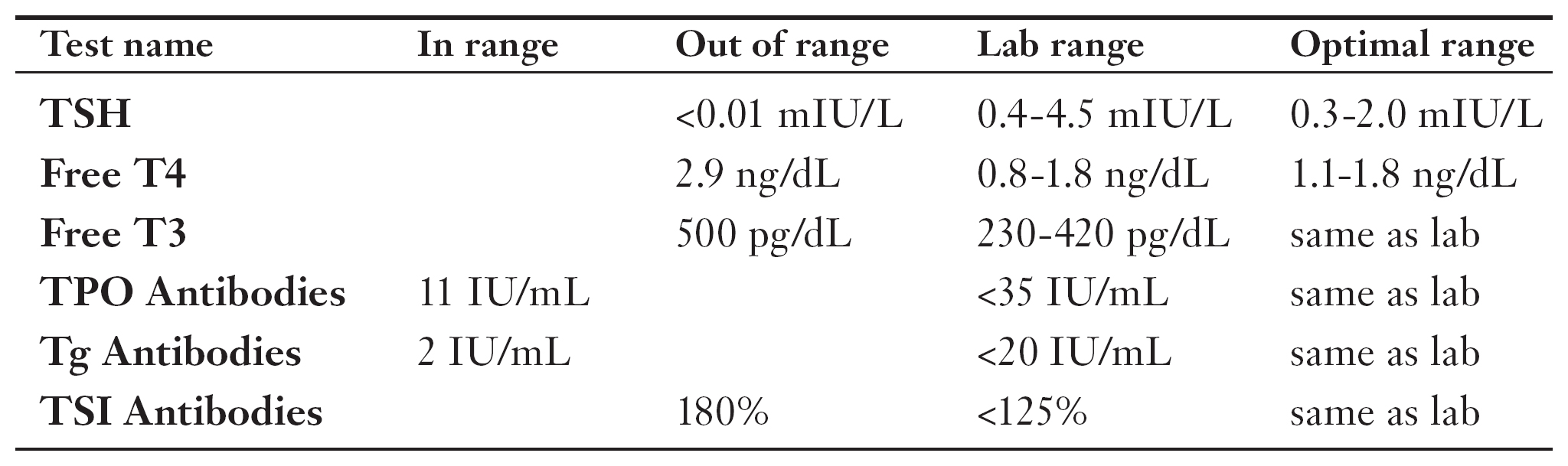

Over-the-Counter

Leonard was a charming gentleman in his 60s who loved to talk about diet and supplements, and took dozens of over-the-counter medications.

Leonard came to me because both of his hands had developed tremors over the past year, and the condition was growing worse. While we talked, I learned that Leonard was also experiencing a rapid heartbeat and trouble sleeping.

I ran a battery of tests. The most significant results were his thyroid blood test numbers: a low TSH, and very high T4 and T3.

I remembered Leonard’s over-the-counter pills, and asked him to bring them all in for me to examine. One of the bottles was for weight loss, and it listed “lyophilized bovine thyroid extract” as an ingredient. The active hormones of non-prescription supplements are supposed to be removed before they’re sold; but these drugs aren’t carefully monitored, and accidents happen. Leonard took four of these pills three times daily. Considering he had no antibody activity, I was pretty sure Leonard’s over-the-counter meds were behind his hyperthyroidism.

I advised Leonard to stop taking his weight loss pills (which weren’t good for him anyway). After four months, Leonard’s TSH, T4, and T3 returned to normal, his tremors went away, his heart rate quieted down, and he once again slept soundly.

The Least You Need to Know

- Your initial hyperthyroidism testing should consist of TSH, free T4, free T3, and antibody blood tests.

- Talk to your doctor about also testing for conditions that cause similar symptoms, such as other autoimmune diseases, heart problems, or bad reactions to medication.

- Request a photocopy of your test results, or have your doctor’s office fax them, and then use this chapter to analyze them.

- If your TSI score is over 125%, you probably have Graves’ disease. Your doctor can verify this via an ultrasound or thyroid scan test. This condition is serious, but highly treatable.