CHAPTER FIVE

MODEL #2: THE TRIANGLE OF SATISFACTION

BACKGROUND OF THE TRIANGLE MODEL

The Triangle is actually a related part of the Circle of Conflict model (Chapter 6) and is taken from the same source, Moore's book The Mediation Process.1 It is, in essence, a deeper layer for analyzing the concept and idea of interests, an idea that is fundamental to the entire conflict resolution field.

DIAGNOSIS WITH THE TRIANGLE OF SATISFACTION

Remembering that “interests,” for the purposes of these first two models, are defined as a party's wants, needs, fears, hopes, or concerns, the Triangle suggests that there are three broad types of these interests. Further, the Triangle proposes that we can map all interests into these three different types, and that these three types are qualitatively different from each other. When working to resolve conflict, each type of interest requires different interventions and different approaches.

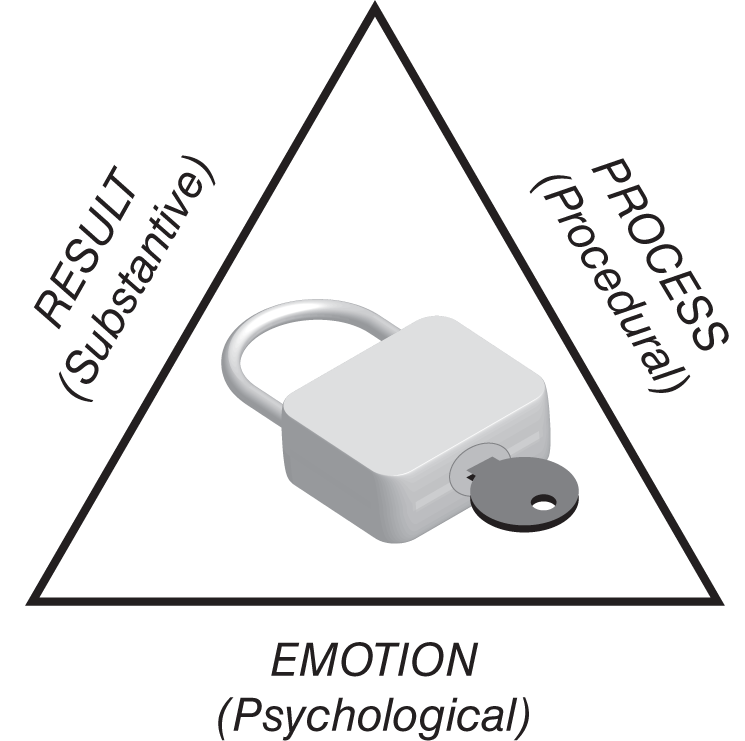

Graphically, the model of the three types of interests looks like Figure 5.1.

Result (Substantive) Interests

This is the “what,” the outcome, the most tangible part of a conflict. In litigation, it's who pays how much money to whom; on a work team, it's the final decision on a contentious issue; in a landlord/tenant issue, it's whether the tenant keeps the apartment, what the new rental amount is, etc.

Figure 5.1 The Triangle of Satisfaction

In a housing transaction, the main result interests of the purchaser may be getting a low final purchase price and including as many light fixtures, appliances, and curtains as possible, whereas the main result interests of the seller may be getting a high sale price in “as is” condition.

Process (Procedural) Interests

This is the “how,” the process by which we reach a result. When the solution is implemented, how fair the process is, how inclusive the process is, how transparent the process is, and who is involved in the negotiation or decision-making process, are all process or procedural interests.

Building on our house purchase example, some process interests might be who presents the offer (the agent or the buyer himself), how fair the negotiation process has been (has the buyer low-balled on their first offer, angering the seller? Has the seller threatened to pull it off the market if they don't like the offer? Is there a bidding war for the property, or is this the only offer in sight?), how long the contingencies for financing or inspection are, and so on.

Emotion (Psychological) Interests

This is what is going on emotionally or psychologically as we try to reach an agreement. Wanting to win, wanting to save face, wanting to be heard, issues of status or self-worth, the quality of the relationship, wanting an apology or wanting revenge, feeling satisfied—these are all psychological or emotional interests parties may have.

In our house-buying example, one psychological or emotional interest may be the question of who gets the antique chandelier; for the buyer it makes the house seem unique and special, whereas for the seller it was her grandmother's and has great emotional value. Although it may be worth little on the market, it may make or break the deal because the parties are emotionally attached to it far beyond its substantive value. In other situations, which party accepts the other's “final offer” may represent who won the negotiation in the parties' minds, and because neither party will want to feel like they lost the negotiation, no deal is struck. Wanting to meet a buyer personally to know the house went to “nice people” may be important from an emotional perspective as well.

The Triangle is used diagnostically on an ongoing basis to assess which type of interest is most important for each party at any given point in time. This can be quite important, because people change their interests, or shift the emphasis of what is important within their interests, as a regular part of the conflict resolution process.

CASE STUDY: TRIANGLE OF SATISFACTION DIAGNOSIS

In our case study, we can apply the Triangle to assess and understand the interests of the parties. As this model is applied, you'll note new details about the case appearing. This is because any practitioner who works with the Triangle model will go out of their way to uncover, explore, and understand the full range of the parties' interests beyond what is initially on the table.

Applying the Triangle to our case study, the interests might look like this:

| BOB'S INTERESTS: | |

| Result Interests: |

|

| Process Interests: |

|

| Psychological Interests: |

|

| SALLY'S INTERESTS: | |

| Result Interests: |

|

| Process Interests: |

|

| Process Interests: |

|

| Psychological Interests: |

|

| DIANE'S INTERESTS: | |

| Result Interests: |

|

| Process Interests: |

|

| Psychological Interests: |

|

There are a few things we can see from the Triangle analysis. First, it requires the practitioner to develop a fairly deep understanding of what is motivating the parties by exploring and understanding their interests. Interests, fundamentally, are what motivate every person to do what they do, to take the actions that they take. Motivation, essentially, is the parties' wants, needs, fears, concerns, and hopes; by assessing and understanding these well beyond the superficial level, the practitioner can gain critical insight into what will be needed for the parties to reach resolution.

Second, as even a cursory read of the interest analysis shows, there are significant areas of “common interest” that can be developed as a foundation for resolution. All human relationships are a mix of common interests and competing interests, and the Triangle helps the practitioner map or understand that dynamic effectively.

Third, and something we don't yet know from this analysis, is the issue of the priority of any of the parties' interests, which ones are deal-breakers and which are simply “nice-to-haves.” Although we can certainly get a sense of what is important to each party through the Triangle analysis, it's only through the negotiation and resolution process itself that we will discover each party's true priorities.

STRATEGIC DIRECTION FROM THE TRIANGLE OF SATISFACTION

The next step is to consider what the practitioner can do based on the Triangle diagnosis.

Strategy #1: Focus on common interests

The practitioner needs to identify and work with the parties around their common interests. Remember, every relationship has a dynamic mix of both common and competing interests. The special nature of conflict, however, is that parties in a conflict will tend to ignore all common interests in order to focus on the competing ones and, further, will tend to focus on the hottest, most provocative competing interest they can find. This is a normal human tendency that unfortunately leads directly to escalation, not resolution. The practitioner's role is to help the parties recognize the common interests that exist in the situation (that exist in every situation) and use those common interests as a basis for resolving the conflict.

Finally, the practitioner can explore the apparently competing interests to see if there's a common interest underlying these competing interests. For example, on a competing interest around money (one party wants more, the other wants to pay less), the common interest may be payment schedules (both want the payment later, the payer for cash flow reasons, the payee for tax reasons). Frequently, interests that appear on the surface to be competing are often obscuring a deeper common interest that can benefit both parties.

Strategy #2: Work with the three types of interests differently

A critical part of the Triangle model is the idea that the practitioner needs to help the parties address all three types of interests to get a good outcome. In addition, each of the three types of interests requires a different approach and different intervention skills.

- Result Interests can be solved, or resolved. They are typically tangible issues that can be negotiated in very direct, hands-on ways. This can happen through a variety of approaches—brainstorming, collaborative problem solving, BATNA (Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement) analysis, competitive bargaining, or compromise. Either way, however, result interests require a tangible, substantive solution acceptable to all parties.

- Process Interests tend not to be solved so much as negotiated on an ongoing basis. As we work to find a full resolution, the process often has to be changed or reinvented. The practitioner must think outside the content of the problem and keep an eye on the structure of the process itself. Substantive problems may benefit from a change in the process by bringing in technical experts to give their input; settlement may be better achieved by the speeding up or slowing down of the negotiation process. Psychological interests may require the symbolic attendance of senior executives. The process must constantly be reevaluated to ensure that it is helping the parties move forward effectively.

- Psychological Interests are never solved. They usually involve how parties feel, and feelings cannot be bargained away or compromised. Psychological interests must be expressed, listened to, acknowledged, processed, and finally released when they are addressed. Emotional/psychological interests need to be addressed respectfully and directly and must be treated as being as important as the other two types of interests. When ignored, emotional interests can become an insurmountable barrier to resolution of the conflict.

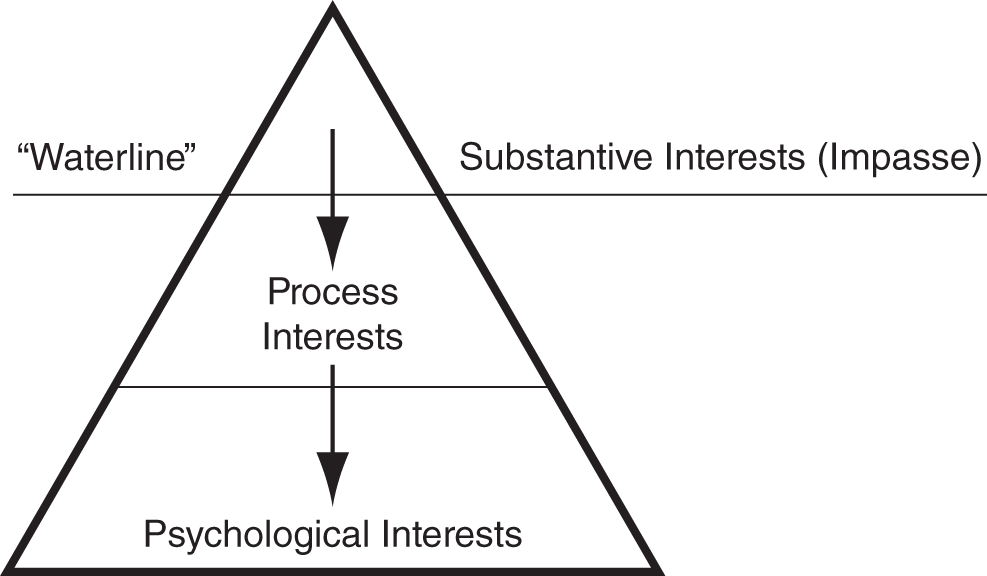

Strategy #3: Move the parties around the Triangle to avoid impasse

The practitioner can use the Triangle to work through impasse, and impasse can be caused by parties getting stuck on any one of the three types of interests. The practitioner needs to effectively move parties around the Triangle (Figure 5.2), shifting the focus to different types of interests at different times to help all parties see the full range of their own interests.

In many circumstances, the resolution of one type of interest is found by working with one of the other types of interests.

Figure 5.2 Triangle of Satisfaction: Strategic direction

Process solutions to results impasse

Sometimes, when the result interests appear incompatible, the parties can agree on a process instead, one that determines the result. They might both accept a third party deciding the result for them, through arbitration. Commercial real estate disputes about lease rates are often resolved by having each party obtain a professional appraisal, and then averaging the two results. In both cases, the parties agree up front to a process that is seen as fair and then accept the solution (result) that the process delivers.

Result or process solutions to psychological impasse

If parties are stuck because of a deep mistrust, one party may unilaterally give the other party a small part of the result they are demanding as a confidence-building measure (CBM).2 This is a result solution to the psychological problem of low trust. Another confidence-building measure is agreeing to a solution based on a third party verifying that each party is adhering to the agreement. By building a process solution (independent verification) into the psychological problem of low trust, parties can continue to interact. Over time, as each side sees the other behaving in a trustworthy fashion, the need for the process step of verification diminishes and trust builds. This can be a process solution to the psychological problem of low trust.

Psychological solutions to result or process impasse

Sometimes, when the impasse is either substantive or procedural in nature (e.g. parties stuck on the outcome or the money, or refusing to even discuss certain issues), the practitioner can guide the parties toward seeing the issues from each other's perspectives. This may mean having each party talk about the impact of the conflict on them personally, how it feels, what it has done to their family or their business or their life. Helping to build some understanding and recognition between the parties (not agreement, just acknowledgment) humanizes each to the other, and may lead to more flexibility in the process and in the results the parties will consider.

Process solutions to psychological impasse

If parties are so angry with one another that they cannot even meet, one solution is to have all communication and interaction take place through an acceptable third party acting simply as a conduit, not a decision-maker. This allows parties to deal with issues, but in a way that prevents direct contact until the emotional side has cooled off enough to allow it. This process of “shuttle diplomacy” can be an effective way to deal with the emotional issues that are blocking resolution.

Clearly, by looking at the three different types of interests at play in any situation of conflict, the practitioner has greater understanding of the motivation and behavior of the parties. Based on this analysis and diagnosis, a great many new interventions are readily apparent.

Let's take a look at how the Triangle can be used strategically in our case study.

CASE STUDY: TRIANGLE OF SATISFACTION STRATEGIC DIRECTION

Once the full range of the parties' interests has been fleshed out through the diagnostic use of the Triangle, the practitioner needs to make some decisions about what to do with these interests. After review, it becomes clear that the main interests seem to be focused between Bob and Sally, with Diane and Bob having a more limited set of interests (though no less important). Because many of the interests seem related to the relationship between Sally and Bob, the following are two possible steps the practitioner can use to intervene:

Step One

The first step is to use the first strategy, Focus on common interests. The mediator could bring Bob and Sally together to confirm and reinforce their common interests, as well as to explore what appear to be competing interests. In doing this, Bob and Sally would recognize that they both want at least some of the following:

- Both want Bob to take on “acting” assignments if he demonstrates a capability and aptitude for this.

- Both want Bob to have at least some access to, and interaction with, Sally (although the level of this still needs to be defined).

- Both want the conflict between them resolved quickly, as it's unpleasant for everyone.

- Both want to avoid this going through a disciplinary process.

- Both acknowledge Bob's long and solid service record to date.

- Both want Bob to have some input and control over the changes going on (although this needs to be within defined parameters).

- Both want a positive, constructive work environment.

- Both want the harassment issue with Diane resolved.

- There appears to be a hot competing interest in that Bob wants Sally punished and Sally wants Bob to admit that he behaved badly. In exploring this, however, the practitioner could find a common interest—both want to be treated respectfully in the workplace and to have the unwanted behavior stopped. What appears to be a competing interest could actually be framed and developed as a common interest.

The mediator, in working through these common interests, starts to set a foundation of hope with the parties that these issues can be resolved.

Step Two

The second step is to use the second and third strategies, Work with the different types of interests differently, and Move the parties around the Triangle to avoid impasse. What follows is how a mediator might apply this step with the parties.

Psychological interests

It was clear from the meetings with Bob and Sally that the psychological interests for Bob were very strong. In the first meeting, after fleshing out the common interests, the mediator asked Bob to describe how he was feeling about the last few months at work. Bob responded by using phrases such as “Discriminated against,” “No value to my work,” “They're trying to force me to quit,” “The last 12 years thrown away,” “Being abused by Diane for standing up for my rights,” and so on. When the mediator asked Sally to describe the workplace, she talked about how Bob's resistance and attitude affected her and others, and how disrespectful she felt his lack of cooperation was, even though she agreed that abuse of any kind was unacceptable. The mediator asked Sally to talk about how she viewed Bob overall. She spoke of Bob's strengths, what Bob was good at, what Bob could improve, his strong service record, and overall how he had been a real asset to the organization. Although this seemed to help, Bob then replied, “If you think I am such a good employee, why didn't I get the promotion?” This allowed the mediator to shift from psychological to process interests.

Process interests

The mediator shifted to process interests by asking Bob how well he understood the competition system, why the union thought it was fair, why management would have bothered rerunning the competition if they just wanted to shut Bob out, how common it was in the workplace for people to not succeed in their first few competitions, etc. Bob replied that he didn't really understand the competition system because it was the first promotion he had applied for, but that Sally should have helped him with it. The mediator also asked Bob what he wanted done differently in the future, and Bob said that although he wanted the promotion, he also wanted more contact with Sally, wanted her help in preparing for any other job openings for AS-1's that came up, and to be included more in the information loop. Sally stated that she was open to all of that if his attitude and behavior changed. This opened the door for a shift to results.

Result interests

The mediator asked Bob to clarify that he wanted to apply for other AS-1 positions, and Bob replied he definitely would. The mediator asked Sally if she could help him with that. Sally stated that she could help by offering “acting” roles and by sending Bob on appropriate training, but only if Bob demonstrated constructive behavior and initiative. Bob agreed, and they discussed and listed specifically how Bob would demonstrate this to Sally, after which Sally would begin offering “acting” roles. This gave Bob clear goals to work on, ones that would help him get specific things from Sally. This shift to the result interests was now starting to define a solution that might work for both.

From a strategic point of view, the practitioner guided the discussions through the three different types of interests and worked with each one in a way appropriate for that particular type:

- Psychological interests were approached through helping the parties listen and acknowledge what they were hearing.

- Process interests were addressed by exchanging a lot of information between the parties, then jointly developing a process that met both their interests.

- Result interests were gently bargained, meaning Sally offered to give Bob what he wanted (acting roles, training) if he gave her what she wanted (demonstration of initiative and constructive choices).

In steps one and two, the practitioner applied all three strategies suggested by the Triangle.

ASSESSING AND APPLYING THE TRIANGLE OF SATISFACTION MODEL

Diagnostically, the Triangle is focused on analyzing the specific interests of each party. Because interests are present for all people in all situations, this model can be applied effectively in virtually every conflict situation. In defining and relating the three different types of interests, it rates high on the scale for diagnostic depth.

Strategically, the Triangle also rates high on the scale for offering specific strategic options in working with the three types of interests, options that flow directly from the diagnosis of the wants, needs, hopes, and fears of the parties in conflict. The three strategies of

- Focusing on common interests,

- Working with the three types of interests differently, and

- Moving the parties around the triangle to avoid impasse

are clearly interrelated and work together well to help the parties get what they need as they move toward resolution.

Final thoughts on the Triangle of Satisfaction

The Triangle is an elegant and simple model that can be used at many levels, both at the surface with just result-type interests, or much deeper through process and psychological interests. In fact, the Triangle is sometimes drawn in a slightly different way to illustrate this, as in Figure 5.3:

Figure 5.3 Triangle of Satisfaction: Deeper interests

From this perspective, the Triangle is presented as an iceberg, with the tip of the iceberg, the part that is most obvious to us, being the result or substantive interests. Below the surface, however, are a range of process interests we need to take into account, and an even deeper layer of emotional interests that we may need to address. If we simply work with what we see on the surface we are likely to suffer the same fate as the Titanic, running aground on the parts of the problem that are not readily apparent but are there, waiting to trip the unwary practitioner who has failed to properly diagnose the problem.

PRACTITIONER'S WORKSHEET FOR THE TRIANGLE OF SATISFACTION MODEL

- Develop the full range of interests for each party, and diagnose by type.

- Focus on common interests and explore competing interests by looking for additional common interests.

Party A's Interests: Party B's Interests: Result: Result: • • • • • • • • Process: Process: • • • • • • • • Psychological: Psychological: • • • • • • • • Common Interests:

•

•

•

•Common Interests:

•

•

•

• - Work with the three types of interests differently. Some specific interventions for each type of interest are:

Result Interests:

- Brainstorm ideas

- Jointly solve problems

- Develop multiple options

- Exchange value, dovetail value

- Consider compromise

- Bargain if necessary

Process Interests:

- Continually negotiate the process to meet the parties' interests

- Include new or different people to change the dynamic at the table

- Think outside the “content” issues of the problem

- Look for objective standards

- Ensure the process is transparent and fair

- Ensure the process is balanced and inclusive

- Keep a future or solution focus, not a past or blame focus

Psychological Interests:

- Don't try to “solve” or bargain people's feelings

- Don't minimize or suppress people's feelings

- Treat as being equally important to the other types of interests

- Listen, acknowledge, and validate feelings

- Don't judge emotional interests; accept them and work through them

- Focus on the future to rebuild relationships

- Uncover, name, and discuss identity issues, and stay focused on the full range of interests

- Move parties around the Triangle to avoid impasse:

- Consider process interventions for results problems

- Consider result interventions for psychological problems

- Consider process interventions for psychological problems

- Consider psychological interventions for process problems

ADDITIONAL CASE STUDY: TRIANGLE OF SATISFACTION

Case Study: Acme Foods

The situation was the termination and wrongful dismissal claim of a 20-year employee. Acme was a very large corporation, with both union and nonunion staff, the latter mostly in management positions. Cathy had worked at Acme as a unionized staff member for 14 years and had been in a supervisory role for five years. One year earlier, she had taken a year-long sabbatical as part of a company “four-for-five” program, which allowed staff to receive 80% of their salary for four years while working full time, and then take a year off and receive 80% of their salary while off. As part of the four-for-five agreement, the company required Cathy to commit to staying at her job for 12 months after her return, or there could be tax consequences. Cathy was the sole breadwinner in her family.

Cathy returned from her sabbatical and was told a restructuring was under way. One month later, she was laid off (along with 12 others) and offered a package of 18 months' notice. She refused to accept this and sued for wrongful dismissal. Cathy at this time was 55 years old, and the company had a retirement policy called an “80 factor,” which meant that when an employee's age and years of service added up to 80, he or she could retire with full retirement income and benefits. Cathy's age and years of work, at this time, added up to 75, which, when combined with the notice period of 1.5 years, took her to 76.5, only 3.5 years short of full retirement. She wanted to find a way to get to her full 80 factor so she could retire with a full pension and benefits.

Cathy claimed that the four-for-five agreement required her to stay for a full year after returning, and the company was obliged to keep her for that year. That would add one year of service and a year to her age, putting her within 1.5 years of the 80 factor. In addition, the four-for-five agreement required she have a mentor in the company to help her find a new position in the company if she were laid off during the sabbatical; the company had not given her this mentor. She claimed that there were jobs she could do in the company, and that the mentor would have helped her find a job internally. Barring that, she claimed that the notice she was being given, because of how she was treated in being terminated, should have been 30 months, adding an additional year to her total. She asked that the company put her on a leave without pay for 6 more months, which would take her to the 80 factor. Finally, she wanted the vice president (VP) of human resources to look at her case, convinced that he would not approve of how she was being treated.

The company, on the other hand, did not even want to consider helping her get to the 80 factor. They were downsizing, they had a hiring freeze, and although they conceded that they hadn't followed the four-for-five agreement exactly, they were not obliged to keep her for a year or to find a new position for her. They said that even if they had appointed her a mentor, no jobs were available so it was irrelevant. In the past, this company had a culture of “cradle to grave” entitlements for employees. Now, new management had set new rules that they felt were fair but not as generous; they were very clear that the rules would not be bent for anyone, because they wanted the message sent that the rules were the rules for all. The VP of human resources was the sponsor of these new rules. Additionally, the company pension plan had just gone from surplus to deficit, so they didn't want to burden it further by helping employees draw from the pension plan years earlier than they were entitled to.

Triangle of Satisfaction diagnosis and worksheet: Acme Foods

| Cathy's Interests: | Acme Food's Interests: |

Result:

|

Result:

|

Process:

|

Process:

|

Psychological:

|

Psychological:

|

Common Interests:

|

Common Interests:

|

From a diagnosis point of view, each party had a full range of interests. In addition, although there was a strong set of competing interests (mostly centered around the result or substantive interests), there were also a number of common interests.

Triangle of Satisfaction strategic direction: Acme Foods

Strategy #1 is to focus on common interests.

| Common Interests Focus: | Possible Intervention Action: |

| Highlight for parties: Both want fair treatment in the final settlement. |

|

| Highlight for parties: Value and appreciate Cathy's years of service, and help Cathy as much as possible. |

|

| Highlight for parties: Cathy's desire to have senior people review the situation, and Acme's desire for Cathy to know their offer meets new company guidelines authorized all the way up the chain of command. |

|

| In caucus, highlight for parties: The desire to close the file and avoid prolonged litigation. |

|

Strategy #2 is to treat different types of interests differently.

| Type of Interest: | Possible Intervention: |

| Substantive Interests: |

|

| Substantive Interests: |

|

| Process Interests: |

|

| Psychological Interests: |

|

Strategy #3 is to move around the Triangle to avoid impasse. In this case, it would mean moving between the interventions described, spending time at the beginning getting some recognition for Cathy's service first, then looking at non-monetary options to help Cathy, then bargaining the numbers for a while, then moving back to arranging a meeting with the senior vice president, then finalizing the numbers through bargaining, then looking at the proposed settlement and comparing it to prolonged litigation and those outcomes, and so on. By moving around and between the different types of interests, the mediator can maximize progress in each area while avoiding getting stuck in any one of them.

Epilogue of the case study

In this case, Cathy fundamentally wanted to get to her 80 factor, and Acme fundamentally refused to make that a goal of theirs. This was headed for an impasse.

To avoid this, the parties spent some time talking about the changes in the workplace coming from the new management team's change in culture and rules. The company rep indicated that the other 11 laid-off employees were treated the same, and although they didn't like it they had accepted it as fair. Acme told a story about one of the 11 who was only 10 months from his 80 factor, and how the company, based on the new policy, would not “bridge” him to get him there. Therefore, out of fairness to all, they could not do so with Cathy. (This discussion focused on process—i.e. fairness—interests.) In addition, the representatives knew Cathy and had worked with her; they acknowledged her years of service and high-quality work, making clear that this was painful and difficult for the company and for them, and most certainly wasn't personal (this acknowledgment focused on the psychological interests.)

Looking at possible resolutions, Acme pointed out they understood her position and indicated that they would help where they could. Acme had a choice to pay any notice as a lump sum (which was easier for the company) or to keep Cathy on payroll for the notice period offered. The difference was that the notice period, if paid through payroll, counted toward her 80 factor and would shorten the time it would take for her to start getting pension benefits. In addition, she would remain on the company benefits plan as opposed to getting cash in lieu, which was important because no individual could get the same quality of benefits plan on their own. If it didn’t settle, however, the company would only pay a lump sum, and it would be of less value to Cathy in terms of her goals.

The lawyers then discussed ranges of notice periods, and they narrowed the range to 20 to 24 months as fair and reasonable. When the offer came from Acme at 22 months, this was seen as acceptable (This was a shift to substantive interests). In addition, on the non-monetary side, Acme agreed to let Cathy know when new positions opened up (not giving her a right of refusal, just knowledge of the position), and Cathy saw this as a benefit.

Finally, Cathy asked to speak with the senior vice president. The Acme reps got him on the line, and Cathy spoke with him for a few minutes. He reiterated the significant change in culture that was taking place, apologized for laying her off, and hoped that the issue would resolve. It was clear to Cathy that this was the best offer she could get, and she felt the company had heard and listened to her (addressing some of her process and psychological interests). The matter settled.

By understanding the different types of interests, and by following the Triangle from a strategic perspective, the practitioner helped the parties focus on meeting their interests in the most effective way possible.