CHAPTER EIGHT

MODEL #5: THE LAW OF RECIPROCITY

with Cal Furlong

BACKGROUND OF THE NATURAL LAWS

This model, along with Loss Aversion Bias in the next chapter, is slightly different than the other models in the book, in that these two are drawn from patterns of behavior that have been identified and repeatedly studied by psychologists, sociologists, and behaviorists for a long time. The research on these cognitive biases is both fascinating and deep, showing just how powerfully they guide our behavior. This information, however, has remained in the realm of research, rarely making its way into common use and practice. That needs to change. These patterns are strong and influential, they help determine a great many of our choices in many settings, and yet they remain largely unconscious, especially in conflict situations. In this and the following chapter, they are presented as simple models to help practitioners diagnose and intervene more effectively by understanding the impact of these unconscious habits on the decisions people make.

By way of background, the Law of Reciprocity and the Loss Aversion Bias operate as if they were “natural laws.” In the hard sciences, natural laws are inviolable principles such as the law of gravity or the three laws of motion—scientifically provable laws of nature. Take the law of gravity as an example. Gravity is a natural law that is so common, so pervasive, that we rarely think of it—yet gravity affects and shapes what we do every waking moment. Humans have adapted to gravity from the beginning, building aqueducts that relied on gravity to function, and pyramids that required lifting massive stones against gravity to construct. In spite of this, it was not until the 1600s that Sir Isaac Newton (and others) named it and defined it as a natural law.

The social sciences have analogous natural laws; here, these principles operate as powerful, often unconscious tendencies that guide and shape much of our actions and decisions in predictable ways. Unlike true natural laws, however, laws in the social sciences are not inviolable. That said, they are strong tendencies that guide and shape our actions in predictable and definable ways.

Take, for example, one such principle from the social science of economics. Human beings have engaged in trading goods and services for thousands of years, and this process of buying, selling, bartering, and exchanging is fundamentally governed by the law of supply and demand. Supply and demand are very powerful predictors of how economic markets work and behave, yet it wasn't until 1776 when Adam Smith described this principle of economics as a “law” that it began to be understood and consciously put to use.

Similarly, the Law of Reciprocity and the Loss Aversion Bias are fundamental patterns of behavior to which people unconsciously and predictably default. The goal of these two chapters is to put these patterns into a simple format that will help practitioners identify and diagnose them in real time and to offer clear strategies to help address and mitigate these biases in order to achieve better outcomes.

THE LAW OF RECIPROCITY

In simple terms, the greatest contributor to the success of humanity on the planet Earth is that we, as a species, learned how to cooperate effectively. Humans are not the fastest, not the strongest, not even the most populous species on Earth, yet humanity has become the most powerful organism on the planet. We did this by learning how to work together to accomplish things far beyond the capabilities of any single person. We learned how to hunt together to kill animals far larger than us, we learned to farm vast areas of land by working together, and we built roads, bridges, and cities on a scale far beyond what any individual could accomplish. The only way any of this could have been accomplished was through cooperation.

The Law of Reciprocity, quite simply, forms the cornerstone of this cooperation1 in human relationships and society.

The Law of Reciprocity is the engine that drives cooperation. It is the underlying process, the instinctual behavior that consistently and unconsciously pushes us toward collaboration and working together for mutual benefit. It is our ability to engage in a complex network of indebtedness and repayment that binds us together into effective and mutually supportive groups. It breaks down individualism and builds tribes, teams, companies, communities, and nations. It is so powerful that there is no society on Earth that does not follow the Law of Reciprocity.2

On the face of it, the law is deceptively simple. The law states:

That is the sum total of reciprocity. And although this looks simple on its face, it means two fundamentally different outcomes are possible, indeed likely, in every interaction we have:

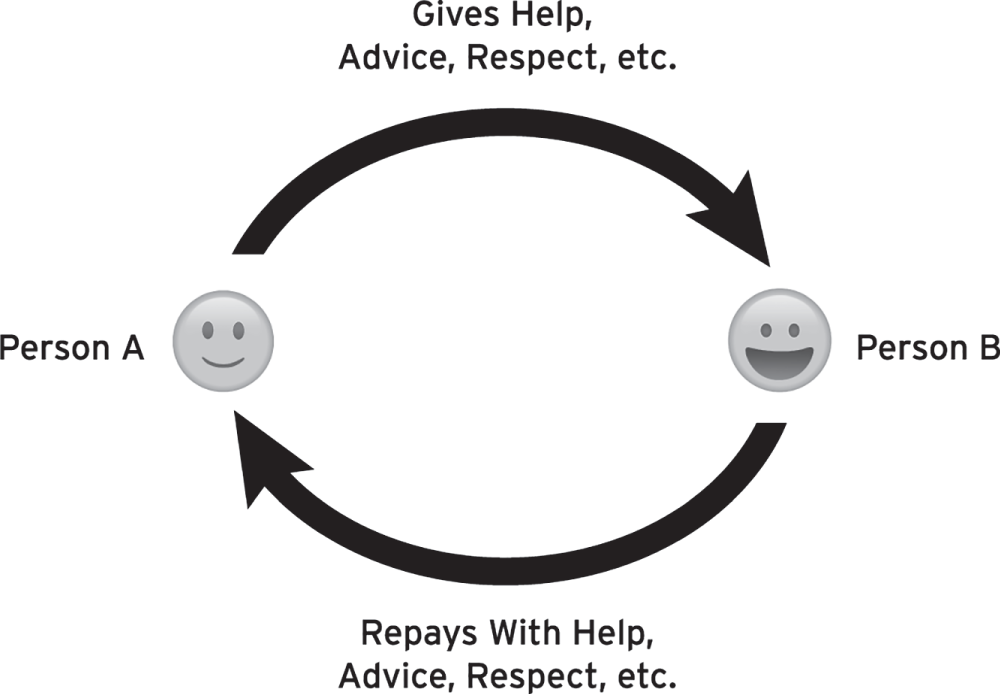

- Outcome #1: If we are given help, advice, respect, and understanding, we feel strongly obliged to return help, advice, respect, and understanding to the other party in kind (Figure 8.2), rather than simply take advantage of it for ourselves.3

Figure 8.2 Positive or constructive reciprocation

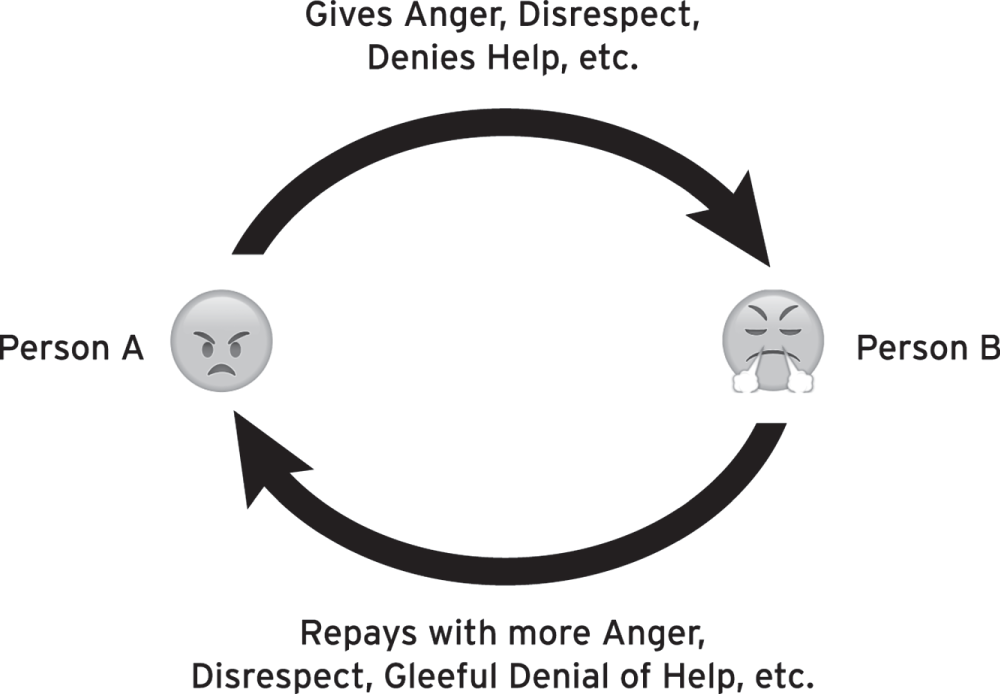

- Outcome #2: If, however, we are given anger, are disrespected, or are denied help, we feel strongly obliged to return the anger, the disrespect, and the denial of help back to the other party (Figure 8.3)—and then some!

Figure 8.3 Negative or destructive reciprocation

The first outcome leads directly to cooperation, collaboration, and an ability to leverage both parties' skills and resources toward better outcomes. The second outcome leads to conflict, to both parties spending time, energy, and money trying to defeat or punish the other. But the good news is this—the law is inherently biased in favor of cooperation. Within the Law of Reciprocity, two guiding principles drive us first and foremost toward cooperation.

- First, we are driven toward helping others. People feel a strong need to help and assist others. How many times have you offered to help neighbors, friends, even strangers on the street? Stories of people risking their own lives to help others—dragging strangers out of burning buildings, jumping into lakes to save drowning children, climbing up the stairs of the Twin Towers on 9/11 to help others get out—are surprisingly common. It is deeply ingrained in us to offer help to other people, in many different situations.

- Second, we often feel obliged to accept help when offered. When offered help, we often accept it for the simple reason that we accomplish our goals faster when we have help. In addition to that, it is actually uncomfortable to refuse help when offered. The times we do refuse help, we often thank the other party profusely for their offer as a way of recognizing the value of the offer itself, as a way of repaying the offer with acknowledgment and thanks at the very least.4 Of course, a big factor in whether we accept help is whether we want to feel obligated to the person offering—a clear acknowledgment of the Law of Reciprocity at work.

To test either of these principles, imagine this: The next time you are invited to dinner at a friend's house, you decide not to bring anything—no wine, no dessert, no flowers, nothing. Think of just how uncomfortable you would feel showing up empty-handed. Or imagine that the next time you ask friends over to your place for dinner, when they arrive with wine, dessert, or flowers, you refuse to accept them. Picture how difficult it would be to say, “No thanks, you keep that,” and just how uncomfortable it would be for everyone involved. We feel bound to offer, and we feel pressure to accept. The Law of Reciprocity overpowers us in many situations, whether we like it or not.

Bringing all three elements together, the Law of Reciprocity boils down to this:

- The main directive of the law is that we must give back or repay to others what it is they have given to us. Unfortunately, this directive can either drive cooperation, or it can drive retaliation and conflict. But the law bends us toward cooperation by relying on two guiding principles:

- We feel compelled to help others, triggering the first step in cooperation.

- We often feel compelled to accept help, reinforcing cooperation.

In virtually every human interaction and every relationship, the Law of Reciprocity is operating. The only question is this: Is reciprocity reinforcing cooperation, or is it driving retaliation and conflict?

DIAGNOSIS WITH THE LAW OF RECIPROCITY

Diagnosing which dynamic of reciprocity is at play is relatively simple—are you witnessing the upward spiral that promotes collaboration, or are you witnessing the downward spiral of self-reinforcing retaliation?

The downward spiral

There can be many causes of friction and conflict in any relationship or interaction, and the other models in the Toolbox can help to identify other possible causes of conflict. In addition to other substantive reasons for conflict, however, a conflict can be both driven and sustained by the Law of Reciprocity alone. Even when both parties want a resolution, the conflict can continue unabated simply because each party feels compelled to reciprocate the most recent negative action the other party has taken. In other words, the conflict can boil down to an ongoing tit-for-tat between the parties, creating a self-reinforcing—and negative—downward spiral (Figure 8.4).

Figure 8.4 The downward spiral

The downward spiral can continue in that direction indefinitely, with each person interpreting the other's behavior as an attack and responding to it with a counterattack. The classic playground justification for this downward spiral is well known—“They started it!” The fuel that sustains an ongoing conflict can simply be each party's negative actions driven by reciprocity. The result is endless conflict and endless time, energy, and money spent on what feels like justice but amounts only to retaliation. The irony is, of course, that both parties, if asked, would likely insist they want it to end. In fact, they would insist that “they are not that kind of person.” But because the Law of Reciprocity is so powerful, they just can't seem to help themselves.

Diagnosing negative reciprocity

Negative reciprocity can be diagnosed by identifying a relatively straightforward pattern. Consider the following questions:

- Is there a pattern of negative behavior between the parties? For how long?

- What specifically is causing the negative behavior? Was it the previous actions of the other party or were there independent causes? Or both?

- Is there an escalation in magnitude as each party responds to the other?

- What is each party's justification for responding the way they did? Are they simply reacting to the other party? Do they have reasons beyond their reaction?

If the pattern is one of deliberate reaction to the previous actions of the other party, and if there is no obvious reason for that reaction other than the other party's behavior, the Law of Reciprocity is likely driving the conflict.

CASE STUDY: RECIPROCITY DIAGNOSIS

Prior to the workplace changes that Sally made, Bob and Diane worked well together.

In Bob's view, he had worked hard and contributed to the organization. He had done a good job for a long time and he was loyal. Now, when a promotion came up and he was the most senior employee, he looked to have his contribution recognized. Instead, the organization gave it to a far newer employee—Diane. He felt disrespected, passed over, his years of commitment and work ignored. He felt demeaned and sidelined. He then reciprocated by filing a grievance. When the union agreed and the competition was rerun, he felt vindicated—until he lost the competition a second time. He then felt even more disrespected and decided to reciprocate again—because the organization was withholding recognition of his long service, he withheld his recognition of Diane's new role. Although he repeatedly said that he had no issue with Diane—which was probably true—he could not accept the new position they had put Diane in. He rejected the organization's decision, risking his own employment to respond in kind to what he saw as unfair treatment.

Diane felt she had worked hard and won the competition fairly—twice. When Bob refused to take her direction, she, in her role as a lead hand, now felt disrespected and treated badly by Bob. Bob refused to take Diane's direction and communicated only with Sally, like Diane didn't exist. This caused Diane to reciprocate with the anger, raised voice, and harsh language she felt he deserved. Bob didn't immediately react to Diane simply because he was responding more to the organization's decision, not to Diane, until she started to treat him disrespectfully. He then reciprocated that disrespect with a complaint against her, accelerating the downward spiral even more.

The organization's decision was seen by Bob as demeaning and he predictably responded with his own negative behavior, which caused Diane to reciprocate with anger, which then caused Bob to dig his heels in even more, leading to worse behavior from Diane, triggering a harassment complaint from Bob. The downward spiral would continue, round and round, until something broke the cycle.

STRATEGIC DIRECTION FROM THE LAW OF RECIPROCITY

The upward spiral

Thankfully, there is another side to this coin of ongoing repayment. Although it can be destructive, the Law of Reciprocity is equally powerful in building and sustaining positive, cooperative relationships. When someone does something helpful for us, we happily look for a chance to help them, which triggers a similar desire in the other person to repay that help with more help, causing us to want to repay that help again, resulting in a chain of mutual help spiraling upward instead of down (Figure 8.5).

Figure 8.5 The upward spiral

Upward spirals can start from scratch, of course. When, for example, we meet someone for the first time and one of us takes an interest, listens, or offers help or support, it builds a positive debt in the other person, and the upward spiral starts.

Other times, however, parties are already in a downward spiral because of a negative interaction, and these negative reactions reinforce each other. To reverse this and change it into an upward spiral, something has to break the negative pattern in the downward spiral first.

Strategy #1: Break the cycle

To break a downward spiral, someone must do something that is completely counterintuitive—they must reverse direction and take an action that is seen to be helping, or offering to help, the other party, contrary to the expected tit-for-tat of another negative response in kind. One party must initiate a constructive action, even in the face of negative behavior from the other party. Often, these counter-intuitive actions are called confidence-building measures.5

There are many actions that can break a downward spiral. Here are some examples:

- A management team starts offering their union information, such as financials, strategic direction, organizational changes being considered, etc., with a request for feedback.

- One country in armed conflict with another unilaterally offers a cease-fire to de-escalate the situation.

- A neighbor with a poor relationship with another neighbor simply starts shoveling the other's sidewalk occasionaly, as a gesture of good faith.

- A union offers to put a contentious grievance in abeyance while the parties work on a broader solution.

Parties in conflict expect negative responses. When they receive a constructive response instead, it often becomes the catalyst to change both parties' actions.

Strategy #2: Leverage one constructive step with another

Once one party has interrupted the downward spiral, either party can leverage this to shift the downward momentum upwards. This can be done because the Law of Reciprocity also relies on one of the most important interests human beings have—reputation.

Reputation is a cornerstone in the evolution of cooperation. Reputation allows for people to trust strangers—but only if they come with a good reputation from their interactions with others. A good reputation often leads to increased business, increased status within groups, even increased wealth. A bad reputation often means being shunned, ignored, or ostracized. People guard their reputation jealously, knowing that if they are seen by others as untrustworthy or unresponsive, they will suffer for it.

When one party breaks the cycle and offers something constructive, if the other party refuses to reciprocate or tries to take advantage of it, they know they will quickly be identified as “the problem.” They will acquire a reputation as being difficult and uncooperative. To prevent this, they will feel pressure to respond in kind, to reciprocate constructively (or at least neutrally). When the first party then sees a positive or even neutral response to their initial action, they, too, will not want to be identified as “the problem” and also feel pressure to respond constructively again. This often leads to the upward spiral, driven just as strongly in a good direction as the downward spiral drives both parties in a negative direction. These constructive steps can quickly lead to a sense of trust, which then again reinforces the upward spiral.

Strategically, then, a practitioner can use this law by encouraging one or both parties to offer a constructive step in the situation, and then use that positive step as a type of “upward spiral” leverage to get the other party to reciprocate. This leverage takes little effort once a constructive pattern has been initiated.

CASE STUDY: RECIPROCITY STRATEGIC DIRECTION

Once an understanding of how negative reciprocity is driving the Bob and Diane conflict has been reached, the practitioner could take specific steps to turn it around.

Step One

The practitioner could meet with Diane and encourage her to take a different approach. Rather than resort to anger and pressure with Bob (which would only result in more resistance and negative behavior), Diane could approach Bob and ask him to take the lead on some customer service projects or clients, something he had complained he wasn't given before. By offering Bob something constructive in spite of his behavior, Diane would be starting the process of interrupting the downward spiral.

The practitioner could also include a union representative in the discussions between Diane and Bob, explaining to the representative that Bob was being offered a chance to gain the experience he had asked for. The union would likely see this as a positive step and reinforce this with Bob as well, counseling him to take advantage of this offer.

The practitioner could also meet with Sally and Bob, leading a discussion on how Sally could meet with Bob (together with Diane) occasionally, to demonstrate to Bob that his voice is important and that he has regular access to Sally, as he did in the past.

Step Two

When Diane sees any constructive responses from Bob, she could then offer Bob an acting assignment as the lead hand, perhaps when Diane was away on vacation or off sick, so that Bob would feel like he is valued and has skills to offer. Bob would almost have to reciprocate with his best effort to make sure he would in no way confirm to Sally, Diane, and the union that he wasn't the right candidate for promotion. He would be virtually driven to do a good job, with the result that he'd start to be reengaged in the workplace instead of withdrawing and refusing to participate.

ASSESSING AND APPLYING THE LAW OF RECIPROCITY

Even though reciprocity can be described as a natural law, it is not foolproof. There are two significant exceptions to the Law of Reciprocity. First, a small number of people seem to be immune to the effects of reciprocity and when offered something constructive, they simply take it and ask for more. The result is one party giving and giving and the other party taking and taking. In this case, a new strategy must be employed.

Rather than continuing to apply the Law of Reciprocity, the giving party must instead rely on the Stairway. A party who accepts a constructive act from another party, refuses to reciprocate and demands more, is simply applying power and will continue to use power until they stop getting what they want. In this case, only an equal application of power in return, followed by a loop-back to interests, will change that party's behavior.6

Second, if one party views the other party as an adversary for some reason, they will refuse to accept anything positive to avoid being indebted to a perceived enemy. In this case, unilaterally applying procedural trust7 in an open and transparent way will slowly undermine the other party's negative attributions and start to open the door to rebuilding the relationship.

Reciprocity is an excellent acid test for relationships of all kinds. If help and support are responded to with help and support, the relationship will likely strengthen and deepen. In the rare instances where cooperation is met with indifference or even competition, it should be taken as an early warning sign of what is likely to follow.

The Law of Reciprocity is a simple, deep, and unconscious driver of behavior in both positive and negative relationships. In addition, the reciprocity strategies can be applied as tools for guiding parties in negative relationships toward a constructive way forward.

ADDITIONAL CASE STUDY—LAW OF RECIPROCITY

The Law of Reciprocity applies even in highly distributive, zero-sum negotiations where relationship tends to play a lesser role.

Case Study: Shooting for the Moon

In a recent personal injury litigation mediation involving a car accident, the plaintiff lawyer, knowing the case was worth approximately $250,000 for his client, made a first offer of $750,000 to the insurance company, including in the claim many damages that were not generally awarded in these kinds of cases. When the insurance company received this offer, they were insulted and started to pack up their files, planning to end the mediation. With effort, the mediator calmed them down and persuaded them to make a counteroffer, which they finally agreed to do. Based on how they saw the plaintiff's offer, however, their offer back was for $1,000—even though they assessed the case as being worth a minimum of $200,000. In other words, they reciprocated what they saw as an insulting offer with an equally insulting offer. Both parties were contributing to a downward spiral.

After discussions with the mediator, the plaintiff's lawyer decided to change the negative tone by making a significant change in their next offer. Even though the $1,000 offer was also seen as insulting, the plaintiff's lawyer positioned themselves as being the first party to be reasonable; their second offer was $295,000—a drop of over $450,000, and a clear confidence-building measure. The insurance company, seeing what they perceived as a conciliatory gesture and a realistic offer, reciprocated constructively with a second offer of $150,000, a similar major move in the negotiation. It took less than an hour for the parties to agree on a settlement of $229,000.

In addition, the insurance company offered a higher than usual amount in a non-taxable category as a way to assist the plaintiff even more. Both parties recovered from a downward spiral, made the shift, and contributed to an upward spiral, even though there was no long-term relationship involved.

NOTES

- 1. The theories on the rise and evolution of cooperation are a fascinating read on their own. For those interested—and it's highly recommended—see Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis, A Cooperative Species (Princeton University Press, 2011) or Robert Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation (Basic Books, 1984).

- 2. Alvin Gouldner, “The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement,” American Sociological Review, Volume 25, Number 2, 161–178, April 1960.

- 3. There are many examples of how different societies have recognized this. When offered help we say “thank you,” but we also say “much obliged,” recognizing an obligation has been created. In Portuguese, thank you is “obrigado,” again signaling obligation. And in Japanese, the word “sumimasen” literally means “this will not end,” indicating that reciprocal obligations continue forever!

- 4. One study showed that those who break the Law of Reciprocity in reverse—by giving help but refusing help offered in return—are disliked for it. Giving selflessly but not allowing repayment also violates reciprocity (K. J. Gergen, P. Ellsworth, C. Maslach, and M. Seipel, “Obligation, Donor Resources, and Reactions to Aid in Three Cultures,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Volume 31, 390–400, 1975).

- 5. See Chapter 7, The Dynamics of Trust, for more information on confidence-building measures.

- 6. See Chapter 4, The Stairway, for a detailed description of the looping-back strategy and how to apply it.

- 7. See Chapter 7, The Dynamics of Trust, for how to build and manage procedural trust.