When you ask most people which software tool they use for their daily data analysis, the answer you most often get is Excel. Indeed, if you were to enter the key words data analysis in an Amazon.com search, you would get a plethora of books on how to analyze your data with Excel. Well if so many people seem to agree that using Excel to analyze data is the way to go, why bother using Access for data analysis? The honest answer: to avoid the limitations and issues that plague Excel.

This is not meant to disparage Excel. Many people across varying industries have used Excel for years, considering it the tool of choice for performing and presenting data analysis. Anyone who does not understand Excel in today's business world is undoubtedly hiding that shameful fact. The interactive, impromptu analysis that Excel can perform makes it truly unique in the industry.

However, Excel is not without its limitations, as you will see in the following section.

Years of consulting experience have brought me face to face with managers, accountants, and analysts who all have had to accept one simple fact: Their analytical needs had outgrown Excel. They all met with fundamental issues that stemmed from one or more of Excel's three problem areas: scalability, transparency of analytical processes, and separation of data and presentation.

Scalability is the ability of an application to develop flexibly to meet growth and complexity requirements. In the context of this chapter, scalability refers to Excel's ability to handle ever-increasing volumes of data. Most Excel aficionados will be quick to point out that as of Excel 2007, you can place 1,048,576 rows of data into a single Excel worksheet. This is an overwhelming increase from the limitation of 65,536 rows imposed by previous versions of Excel. However, this increase in capacity does not solve all of the scalability issues that inundate Excel.

Imagine that you are working in a small company and you are using Excel to analyze your daily transactions. As time goes on, you build a robust process complete with all the formulas, pivot tables, and macros you need to analyze the data stored in your neatly maintained worksheet.

As your data grows, you will first notice performance issues. Your spreadsheet will become slow to load and then slow to calculate. Why will this happen? It has to do with the way Excel handles memory. When an Excel file is loaded, the entire file is loaded into memory. Excel does this to allow for quick data processing and access. The drawback to this behavior is that each time something changes in your spreadsheet, Excel has to reload the entire spreadsheet into memory. The net result in a large spreadsheet is that it takes a great deal of memory to process even the smallest change in your spreadsheet. Eventually, each action you take in your gigantic worksheet will become an excruciating wait.

Your pivot tables will require bigger pivot caches, almost doubling your Excel workbook's file size. Eventually, your workbook will be too big to distribute easily. You may even consider breaking down the workbook into smaller workbooks (possibly one for each region). This causes you to duplicate your work. Not to mention the extra time and effort it would take should you want to recombine those workbooks.

In time, you may eventually reach the 1,048,576-row limit of your worksheet. What happens then? Do you start a new worksheet? How do you analyze two datasets on two different worksheets as one entity? Are your formulas still good? Will you have to write new macros?

These are all issues you need to deal with.

Of course, you will have the Excel power-users, who will find various clever ways to work around these limitations. In the end, though, they will always be just workarounds. Eventually, even these power-users will begin to think less about the most effective way to perform and present analysis of their data and more about how to make something "fit" into Excel without breaking their formulas and functions. Excel is flexible enough that a proficient user can make most things fit into Excel just fine. However, when users think only in terms of Excel, they are undoubtedly limiting themselves, albeit in an incredibly functional way.

In addition, these capacity limitations often force Excel users to have the data prepared for them. That is, someone else extracts large chunks of data from a large database and then aggregates and shapes the data for use in Excel. Should the serious analyst always be dependent on someone else for his or her data needs? What if an analyst could be given the tools to access vast quantities of data without being reliant on others to provide data? Could that analyst be more valuable to the organization? Could that analyst focus on the accuracy of the analysis and the quality of the presentation, instead of routing Excel data maintenance?

Access is an excellent (many would say logical) next step for the analyst who faces an ever-increasing data pool. Since an Access table takes very few performance hits with larger datasets and has no predetermined row limitations, an analyst can handle larger datasets without requiring the data to be summarized or prepared to fit into Excel. Since many tasks can be duplicated in both Excel and Access, an analyst proficient at both will be prepared for any situation. The alternative is telling everyone, "Sorry, it is not in Excel."

Also, if ever a process becomes more crucial to the organization and needs to be tracked in a more enterprise-acceptable environment, it will be easier to upgrade and scale up if that process is already in Access.

Note

An Access table is limited to 256 columns but has no row limitation. This is not to say that Access has unlimited data storage capabilities. Every bit of data causes the Access database to grow in file size. An Access database has a file-size limitation of 2 gigabytes.

One of Excel's most attractive features is its flexibility. Each cell can contain text, a number, a formula, or practically anything else the user defines. Indeed, this is one of the fundamental reasons Excel is such an effective tool for data analysis. Users can use named ranges, formulas, and macros to create an intricate system of interlocking calculations, linked cells, and formatted summaries that work together to create a final analysis.

So what is the problem with that? The problem is that there is no transparency of analytical processes. Thus, it is extremely difficult to determine what is actually going on in a spreadsheet. Anyone who has had to work with a spreadsheet created by someone else knows all too well the frustration that comes with deciphering the various gyrations of calculations and links being used to perform some analysis. Small spreadsheets performing modest analysis are painful to decipher, while large, elaborate, multi-worksheet workbooks are virtually impossible to decode, often leaving you to start from scratch.

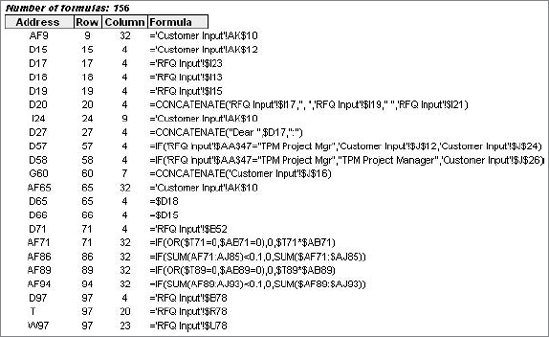

Even auditing tools available with most Excel add-in packages provide little relief. Figure 1-1 shows the results of a formula auditing tool run on an actual workbook used by a real company. It's a list of all the formulas in this workbook. The idea is to use this list to find and make sense of existing formulas. Notice that line one shows that there are 156 formulas. Yeah, this list helps a lot; good luck.

Compared to Excel, Access might seem rigid, strict, and unwavering in its rules. No, you can't put formulas directly into data fields. No, you can't link a data field to another table. To many users, Excel is the cool gym teacher who lets you do anything, while Access is the cantankerous librarian who has nothing but error messages for you. All this rigidity comes with a benefit, however.

Since only certain actions are allowable, you can more easily come to understand what is being done with a set of data in Access. If a dataset is being edited, a number is being calculated, or if any portion of the dataset is being affected as a part of an analytical process, you will readily see that action. This is not to say that users can't do foolish and confusing things in Access. However, you definitely will not encounter hidden steps in an analytical process such as hidden formulas, hidden cells, or named ranges in dead worksheets.

Data should be separate from presentation; you do not want the data to become too tied to any particular way of presenting it. For example, when you receive an invoice from a company, you don't assume that the financial data on that invoice is the true source of your data. Rather, it is a presentation of your data. It can be presented to you in other manners and styles on charts or on Web sites, but such representations are never the actual source of data. This sounds obvious, but it becomes an important distinction when you study an approach of using Access and Excel together for data analysis.

What exactly does this concept have to do with Excel? People who perform data analysis with Excel, more often than not, tend to fuse the data, the analysis, and the presentation together. For example, you will often see an Excel Workbook that has 12 worksheets, each representing a month. On each worksheet, data for that month is listed along with formulas, pivot tables, and summaries. What happens when you are asked to provide a summary by quarter? Do you add more formulas and worksheets to consolidate the data on each of the month worksheets? The fundamental problem in this scenario is that the worksheets actually represent data values that are fused into the presentation of your analysis. The point here is that data should not be tied to a particular presentation, no matter how apparently logical or useful it may be. However, in Excel, it happens all the time.

In addition, as previously discussed, because all manners and phases of analysis can be done directly within a spreadsheet, Excel cannot effectively provide adequate transparency to the analysis. Each cell has the potential of holding formulas, becoming hidden, and containing links to other cells. In Excel, this blurs the line between analysis and data, which makes it difficult to determine exactly what is going on in a spreadsheet. Moreover, it takes a great deal of effort in the way of manual maintenance to ensure that edits and unforeseen changes don't affect previous analyses.

Access inherently separates its analytical components into tables, queries, and reports. By separating these elements, Access makes data less sensitive to changes and creates a data analysis environment where you can easily respond to new requests for analysis without destroying previous analyses.

Many who use Excel will find themselves manipulating its functionalities to approximate this database behavior. If you find yourself in this situation, you must consider that if you are using Excel's functionality to make it behave like a database application, perhaps the real thing just might have something to offer. Utilizing Access for data storage and analytical needs would enhance overall data analysis and would allow the Excel power-user to focus on the presentation in his or her spreadsheets.

In the future, there will be more data, not less. Likewise, there will be more demands for complex data analysis, not fewer. Power-users are going to need to add some tools to their repertoire in order to get away from being simply spreadsheet mechanics. Excel can be stretched to do just about anything, but maintaining such creative solutions can be a tedious manual task. You can be sure that the sexy part of data analysis is not in routine data management within Excel. Rather, it is in the creation of slick processes and utilities that will provide your clients with the best solution for any situation.

After such a critical view of Excel, it is important to say that the key to your success in the sphere of data analysis will not come from discarding Excel altogether and exclusively using Access. Your success will come from proficiency with both applications and the ability to evaluate a project and determine the best platform to use for your analytical needs. Are there hard-and-fast rules you can follow to make this determination? The answer is no, but there are some key indicators in every project you can consider as guidelines to determine whether to use Access or Excel. These indicators are the size of the data; the data's structure; the potential for data evolution; the functional complexity of the analysis; and the potential for shared processing.

The size of your dataset is the most obvious consideration you will have to take into account. Although Excel can handle more data than in previous versions, it is generally a good rule to start considering Access if your dataset begins to approach 100,000 rows. The reason for this is the fundamental way Access and Excel handle data.

When you open an Excel file, the entire file is loaded into memory to ensure quick data processing and access. The drawback to this behavior is that Excel requires a great deal of memory to process even the smallest change in your spreadsheet. You may have noticed that when you try to perform an AutoFilter on a large formula-intensive dataset, Excel is slow to respond, giving you a Calculating indicator in the status bar. The larger your dataset is, the less efficient the data crunching in Excel will be.

Access, on the other hand, does not follow the same behavior as Excel. When you open an Access table, it may seem as though the whole table is opening for you, but in reality, Access is storing only a portion of data into memory at a time. This ensures the cost-effective use of memory and allows for more efficient data crunching on larger datasets. In addition, Access allows you to make use of Indexes that enable you to search, sort, filter, and query extremely large datasets very quickly.

If you are analyzing data that resides in a table that has no relationships with other tables, Excel is a fine choice for your analytical needs. However, if you have a series of tables that interact with each other (such as a Customers table, an Orders table, and an Invoices table), you should consider using Access. Access is a relational database, which means it is designed to handle the intricacies of interacting datasets. Some of these are the preservation of data integrity, the prevention of redundancy, and the efficient comparison and querying of data between the datasets. You will learn more about the concept of table relationships in Chapter 2.

Excel is an ideal choice for quickly analyzing data used as a means to an end, such as a temporary dataset crunched to obtain a more valuable subset of data. The result of a pivot table is a perfect example of this kind of one-time data crunching. However, if you are building a long-term analytical process with data that has the potential of evolving and growing, Access is a better choice. Many analytical processes that start in Excel begin small and run fine, but as time passes these processes grow in both size and complexity until they reach the limits of Excel's capabilities. The message here is that you should use some foresight and consider future needs when determining which platform is best for your scenario.

There are far too many real-life examples of analytical projects where processes are forced into Excel even when Excel's limitations have been reached. How many times have you seen a workbook that contains an analytical process encapsulating multiple worksheets, macros, pivot tables, and formulas that add, average, count, look up, and link to other workbooks? The fact is that when Excel-based analytical processes become overly complex, they are difficult to manage, difficult to maintain, and difficult to translate to others. Consider using Access for projects that have complex, multiple-step analytical processes.

Although it is possible to have multiple users work on one central Excel spreadsheet located on a network, ask anyone who has tried to coordinate and manage a central spreadsheet how difficult and restrictive it is. Data conflicts, loss of data, locked-out users, and poor data integrity are just a few examples of some of the problems you will encounter if you try to build a multiple-user process with Excel. Consider using Access for your shared processes. Access is better suited for a shared environment for many reasons, some of which are:

The ability for users to concurrently enter and update data

Inherent protection against data conflicts

Prevention of data redundancy

Protection against data entry errors

Many seasoned managers, accountants, and analysts come to realize that just because something can be done in Excel does not necessarily mean Excel is the best way to do it. This is the point when they decide to open Access for the first time. When they do open Access, the first object that looks familiar to them is the Access table. In fact, Access tables look so similar to an Excel spreadsheet that most Excel users try to use tables just like a spreadsheet. However, when they realize that they can't type formulas directly into the table or duplicate most of Excel's behavior and functionality, most of them wonder just what exactly the point of using Access is.

When many Excel experts find out that Access does not behave or look like Excel, they write Access off as too difficult or as taking too much time to learn. However, the reality is that many of the concepts behind how data is stored and managed in Access are those with which the user is already familiar. Any Excel user has already learned such concepts in order to perform and present complex analysis. Investing a little time up front to see just how Access can be made to work for you can save a great deal of time in automating routine data processes.

Throughout this book, you will learn various techniques in which you can use Access to perform much of the data analysis you are now performing exclusively in Excel. This section is a brief introduction to Access from an Excel expert's point of view. Here, you will focus on the big-picture items in Access. If some of the Access terms mentioned here are new or not terribly familiar, be patient. They will be covered in detail as the book progresses.

What will undoubtedly look most familiar to you are Access tables. Tables appear almost identical to spreadsheets with familiar cells, rows, and columns. However, the first time you attempt to type a formula in one of the cells, you will see that Access tables do not possess Excel's flexible, multi-purpose nature that allows any cell to take on almost any responsibility or function.

The Access table is simply a place to store data, such as numbers and text. All of the analysis and number crunching happens somewhere else. This way, data will never be tied to any particular analysis or presentation. Data is in raw form, which leaves users to determine how they want to analyze or display it.

Chapter 2 will help you get started with a gentle introduction to Access basics.

You may have heard of Access queries but have never been able to relate to them.

Consider this: In Excel, when you use AutoFilter, a VLookup formula, or Subtotals, you are essentially running a query. A query is a question you pose against your data in order to get an answer or a result. The answer to a query can be a single data item, a Yes/No answer, or many rows of data. In Excel, the concept of querying data is a bit nebulous, as it can take the form of the different functionalities, such as formulas, AutoFilters, and PivotTables.

In Access, a query is an actual object that has its own functionalities. A query is separate from a table, ensuring that data is never tied to any particular analysis. You will cover queries extensively in subsequent chapters. Your success in using Microsoft Access to enhance your data analysis will depend on your ability to create all manners of both simple and complex queries.

Chapter 3 begins your full emersion into all the functionality you can get from Access queries.

Access reports are an incredibly powerful component of Microsoft Access, which allow data to be presented in a variety of styles. Access reports, in and of themselves, provide an excellent illustration of one of the main points of this book: Data should be separate from analysis and presentation. The report serves as the presentation layer for a database, displaying various views into the data within. Acting as the presentation layer for your database, reports are inherently disconnected from the way your data is stored and structured. As long as the report receives the data it requires in order to accurately and cleanly present its information, it will not care where the information comes from.

Access reports can have mixed reputations. On one hand, they can provide clean-looking PDF-esque reports that are ideal for invoices and form letters. On the other hand, Access reports are not ideal for showing the one-shot displays of data that Excel can provide. However, Access reports can easily be configured to prepare all manners of report styles, such as crosstabs, matrices, tabular layouts, and subtotaled layouts. You'll explore all the reporting options available to you starting in Chapter 11.

Just as Excel has macro and VBA functionality, Microsoft Access has its equivalents. This is where the true power and flexibility of Microsoft Access data analysis resides. Whether you are using them in custom functions, batch analysis, or automation, macros and VBA can add a customized flexibility that is hard to match using any other means. For example, you can use macros and VBA to automatically perform redundant analyses and recurring analytical processes, leaving you free to work on other tasks. Macros and VBA also allow you to reduce the chance of human error and to ensure that analyses are preformed the same way every time. Starting in Chapter 9, you will explore the benefits of macros and VBA and how you can leverage them to schedule and run batch analysis.

Although Excel is considered the premier tool for data analysis, Excel has some inherent characteristics that often lead to issues revolving around scalability, transparency of analytic processes, and confusion between data and presentation. Access has a suite of analytical tools that can help you avoid many of the issues that arise from Excel.

First, Access can handle very large datasets and has no predetermined row limitation. This allows for the management and analysis of large datasets without the scalability issues that plague Excel. Access also forces transparency—the separation of data and presentation by separating data into functional objects (that is, tables, queries, and reports) and by applying stringent rules that protect against bad processes and poor habits.

As you go through this book, it is important to remember that your goal is not to avoid Excel altogether but rather to broaden your toolset and to understand that, often, Access offers functionality that both enhances your analytical processes and makes your life easier.