5

Organizing for Experience Centricity

Great experiences are provided by the whole organization, where everyone has a part. This chapter describes how you can structure the organization around a carefully crafted combination of formal and informal organizational culture. It integrates design and design thinking into organizational change, showing how you can design your organizational logics to align with the experience you want to provide. It introduces the idea of organizational prototyping, which applies design thinking principles so you can approach organizational change in the same way you approach innovation, by design.

Innovation in service has been described as the unique application of organizational competencies and ways of working and thinking to create value in use. This chapter introduces the new competencies, ways of working, and ways of thinking that an organization must develop on its path to experience centricity. It uses design thinking as the basis for what I term experience thinking and experience doing, which can be characterized as having the customer experience at heart, being customer-centric, visual, culturally aware, and collaborative, and simultaneously retaining the powers of being effective and efficient at service delivery. Developing experience-centric organizations is a team sport, where everyone has their part.

When you watch the credits of a film, you see how many people worked together to provide the experience you had during the previous couple of hours. The credits also include people who are indirectly involved—people in accounting and finance, for example—because there is a recognition that a film is a huge collective effort. The same mindset should apply to your organization: everyone is involved, and everyone is necessary. This includes the customer (it is strange how much organizational design ignores the customer; it’s as if they do not exist). This approach makes all employees stakeholders, and recognizes that the customer is a stakeholder too. Indeed, the experience-centric organization is a co-designed and co-produced organization.

The customer experience is a reflection of the organization that delivers it, and the experience-centric organization requires an experiential way of thinking and doing as its cornerstone. The organization as a whole needs to be structured to support and play a part in the experience that is provided to customers, because the whole organization is involved in its production. Everybody contributes to the customer experience, and everybody has to feel that they contribute. This means both a sense of part-ownership, along with the pride that goes with it, and an understanding of their role in making it happen.

To achieve experience centricity, you’ll need to design new or updated organizational logics that are aligned around the customer experience. That is the theme of this chapter: what you’ll need to transform your existing organizational logics into experience-centric ones.

Doing What You Love, and Loving What You Do

The great motivation researcher, Teresa Amabile had a mantra: people are most creative when they are doing what they love, and loving what they are doing.1 This idea is mirrored by the famous researcher in flow Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who describes flow as complete absorption in what one does, resulting in a loss of one’s sense of space and time.2 Both explanations are relevant to the experience-centric organization, because great experiences come from motivated and focused employees.

To enable the necessary aspects of alignment, infusion, and orchestration, it is important that people feel that they are a part of something greater, and have a sense of co-ownership of the customer experience. This requires two things:

- An intrinsic motivation in the organization’s employees to be a part of the grand scheme of the experience (that is, every individual identifies with the experiential mission of the organization)

- A way of working and a structure of work such that individuals feel that they are enabled by the organization to contribute in the best way they can

This is why the authenticity of purpose of the organization should be clear. The clearer it is, the easier it is to recruit people to the organization, motivate them, and develop structures to assist them. Further, authenticity of purpose creates a self-selection of employees, as people who do not align with the organization will leave. If people do what they love in work, and are enabled to love what they are doing, you will have a well-functioning organization.

Who Owns the Customer Experience

A discussion about who owns the customer experience within the organization is central and needs to be clarified early on. The customer owns the experience in the sense that they have the experience and their perception of experiential value is key. At the same time, everyone in the organization should feel that they contribute to the experience and, in that way, have some ownership of it.

From the organizational perspective there needs to be clear understanding about who is responsible for ensuring a great experience and who is responsible for designing for this experience. These are two different things. The CEO is responsible for ensuring that the experience can be delivered and obtaining organizational alignment around it. The CXO is responsible for its design. The CXO is analogous to the director of a film, and therefore should have creative responsibility for developing the experience vision and designing for it. This is not the same as artistic vision, since the CXO has to balance feasibility, viability, and desirability: feasibility in terms of being able to deliver the experience, viability in terms of it creating mutual value, and desirability in terms of customers loving it. This is a critical position and the CXO needs to be chosen carefully, since it is an interpretive role. The experience director interprets the DNA of the company and the zeitgeist of the market to develop an experiential vision. The CEO is a key partner in this, and has the role of translating the vision into action together with the rest of the leadership.

The interplay between the CEO and CXO is important, as is the relationship between the CXO and the rest of the leadership. The CXO has to be a team player while also being welcomed as such by the others in the team. The dynamic of this new role and the interactions between the different team members are key to the success of the transformation you are embarking on.

Designing Organizational Logics

The term organizational logics describes how an organization works—that is, the ways of thinking, believing, and doing in the organization.3 Organizational logics are unique to the organization, and while it may mot be easy to describe them, they are always there. When someone says, “That’s not how things are done around here,” they are referring to a logic that the organization uses, but perhaps has never explicitly defined. Your organization has multiple logics, and most likely they are not experience-centric, so this means you will have to transform them.

Organizational logics are systemic, structural, and cultural. They’re systemic because an organization is based on systems, each designed and put together in a particular way to achieve something (i.e., some logic was applied to define what these systems should achieve and do). They’re structural because organizations are made up of governing structures and rules. However, organizational logics are also highly cultural, since they are based on beliefs, expectations, and values. Cultural logics relate to motivation and the organization’s reason to be, and are therefore central to the organization’s identity. In this way, they form a central part of your experiential DNA and are therefore important to identify and change.

This combination of systemic, structural, and cultural logics defines how the organization thinks and works, and its development over time has made your organization what it is today. These logics make a particular kind of sense within the organization and are not really thought about, as they have always been there. They’re something you get to know when you start to work in an organization and something you need to transform as the world changes around you. As you shift toward becoming an experience-centric organization, you will have to design new organizational logics, recognize the logics you have now, and plan a transition. During this transformation, you will have to focus more on cultural aspects, since the customer experience is often a reflection of the internal culture of an organization. The structural side, therefore, should be seen as a support for the culture you want the organization to have, and for the experience you wish to provide.

We talked earlier about enabling the organization to deliver the right experience, about alignment in the organization, shared ownership of the experience, and the infusion of experiential thinking throughout the organization. All of these are central parts of the organizational logics you need to have in place.

The Importance of a Symbolic Focus

Since experience relates to emotions, meaning, and feelings, the symbolic aspects of your organizational logics have particular importance. This is why I emphasize the importance of leadership, and particularly leadership actions. As you’ll see in Chapters 9 and 10, the experience-centric organization reacts to cultural meaning, but it is also a part of it and even forms it. Every action by the organization will be viewed through a cultural lens, and many will be given symbolic meaning. If a leader places their office among the call center staff, it says something about their role and importance in the organization. If the CEO of Harley Davidson goes to a hog rally, it speaks as much to Harley staff as it does to hog owners about the importance of customers and motorcycle culture. If the story about an employee who goes the extra mile for a customer is retold and becomes a legend in the organization, it says something about their focus on customer experience. It both influences the organization and reveals something about it.

When we hear that Sony CEO Akio Morita had a special jacket made to enable him to carry new Sony products in development, that says something about his focus on innovation. When the CEO of Ryanair (a low-cost Irish carrier) says he is considering charging customers for going to the toilet on flights, that says something about his attitude toward economy flights and customers. When a customer goes to the effort of writing a song about his guitar being broken by an airline’s baggage handler,4 it becomes a symbol of customer relations within that airline. Myths and stories form an important part of the symbolic fabric of your organization, so when transforming the organization, you must understand the deeper meaning of actions and design those symbols into the transformation. Which stories do you want to be told within your organization? Which ones are told now?

Creating Alignment and Empowerment Within the Organization: The Top-Up Approach

The top-up approach mixes a top-down leadership message with a bottom-up empowerment model. Leadership is important, and it is vital that leaders take a lead in the experience-centric organization. They are better placed than others to transmit ideas because they command attention within the organization. Those ideas can be transformative because they easily become symbolic, and can be backed up through structural actions. Leadership views have to be seen in the organization as guiding lights toward experience centricity.

At the same time, the experience-centric organization recognizes that the customer experience occurs in the interactions between the customer and the employees (or other touchpoints). This requires enabling and empowering the front line to be able to deliver on experiential expectations. The top-down approach needs to be supported by a bottom-up one, and starting with the interactions is a great way of achieving this.

One of the benefits of focusing on the experience is that everyone can relate to it, and it has the effect of aligning dissenting views or approaches within the organization. The customer experience is something that everyone can understand and relate to personally. It creates a clarity of purpose within the organization, and has a logic that few can argue against. Therefore, taking an experiential focus can relieve internal tensions in the organization and create high-level agreement. When this focus is coupled to the adoption of the wheel of experience centricity, it creates structures and roles that the entire organization can embrace. Add to this the interaction-out approach, described in the following section, and you’ll gain the alignment you need.

The Interaction-Out Approach: Working from the Experience Outward

The experience-centric organization knows what experience it wants its customers to have. This is the starting point for designing and discussing how the experience can be fulfilled through the touchpoints of the service.

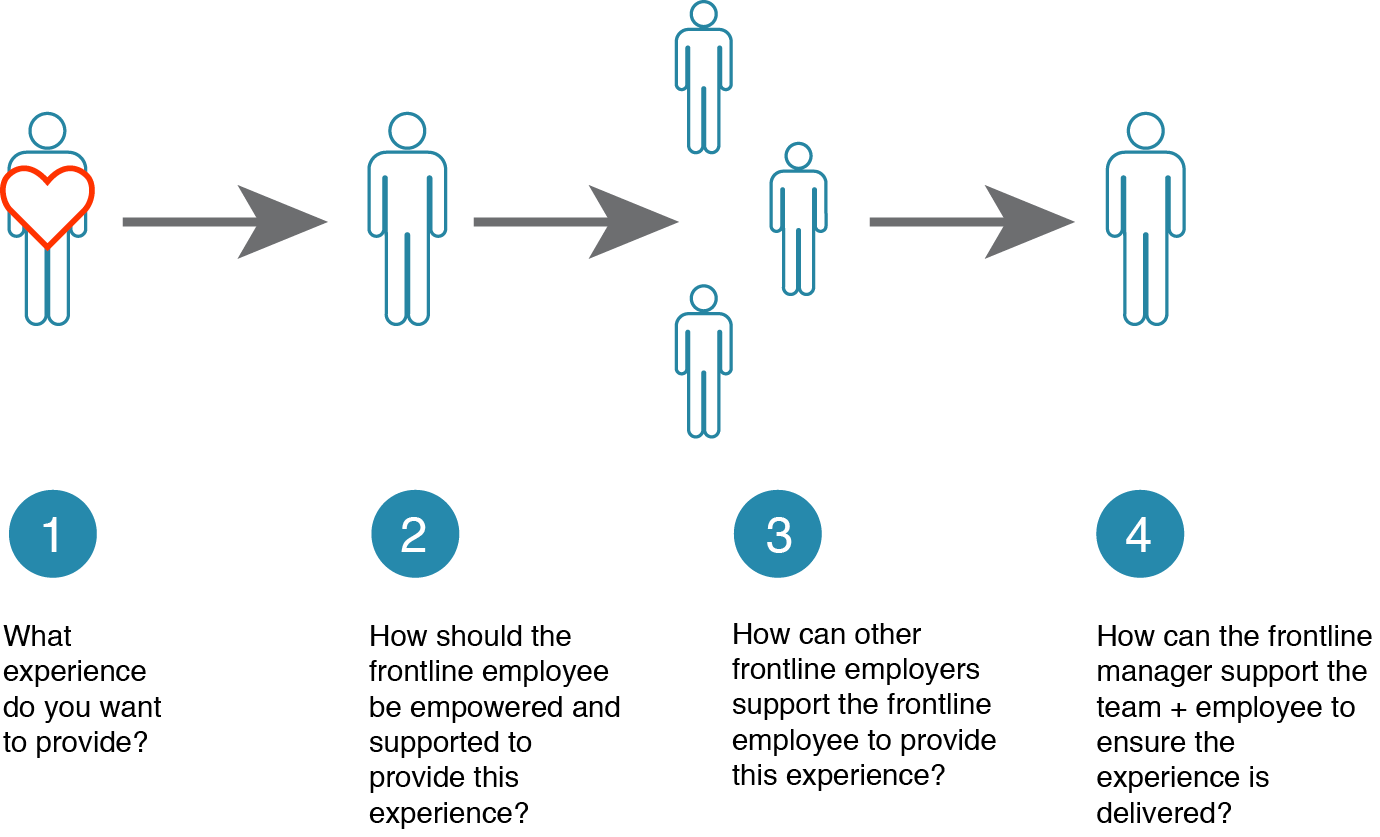

The interaction-out approach, illustrated in Figure 5-1, can be used by a cross-functional development team. It starts with the experience and the question: “If we want to give experience X, then what should we do as an organization to empower the employee (or technology) to co-produce this experience together with the customer?” That will give you a focus on the employee experience (or touchpoint design) and how to enable it. Then it is possible to work backward, and discuss how to enable the frontline employer through the team or group working together. Here the focus can be on formal and informal organization. Further back again, we can ask, “What should the team leader do to enable the team to deliver the experience?” This can continue further and further out into the organization to create a structure, a way of thinking, and a way of working.

All the time, you can use the wheel of experience centricity to discuss experience fulfillment, enabling, and structure. What platforms do we need such that the touchpoint potential can be fulfilled? What structure do we need to have a viable business model? This inverts the traditional push hierarchical view to being one of experience pull, where the moment of truth—the customer experience—is in focus.

Figure 5-1. The interaction-out approach forces you to start with the experience and then ensure that the touchpoints (in this case frontline employees) are enabled to provide this experience. In this way, you work from the experience outward, and can define the role of other employees and managers.

Rotating Jobs to Develop Experiential Empathy

Earlier chapters have stressed the importance of “experiencing the experience” during design and development, but this also applies to others in the organization who may be far away from the customer experience. To get on board, they have to experience the experience the organization provides from a customer’s point of view. When a janitor at NASA famously said in the 1960s that he was not cleaning offices but helping put a man on the moon, he was demonstrating employee alignment with the overarching mission of the organization. Likewise, in the experience-centric organization there is alignment among employees, and job rotation—hosting people from other departments—can be a means of understanding what the intended experience is, how difficult it is to provide it, how important it is to customers, and how essential it is that everyone contribute to the mission. The closer you are to the customer, the easier it is to understand this, but as mentioned, not all functions in the company are close to the customer. Therefore, job rotation is a good way to imprint on all members of the organization what it means to provide a fantastic experience. The CEO and CXO need to be a part of this exercise as well, both for the symbolic effect, which cannot be underestimated, and for the practical learning they will bring back to the leadership team.

Infusion as Part of a Design Strategy

I have used the term infusion a lot in this book, because it is a strong means of creating change within the organization. As explained before, infusion can be likened to placing a tea bag in water and watching the color spread. So, we could say that infusion works by dripping important aspects into the organization at the right places, and supporting their spread. These drips usually are a mix of light-bulb moments, symbolic acts, and some formal process changes.

Remember that for organizational change to happen, the organizational logics need to transform. Infusion is a powerful way to accomplish this transformation. Infusing an organization successfully requires a carefully designed infusion strategy. Although infusion might appear to be a spontaneous set of occurrences, it is important to plan them and have a structure for them. Sometimes they happen by themselves, due to natural communication from leaders and managers, but they always have to be supported by planned actions. These can be courses, social media, formal process changes, myths, stories, news articles, and even concept services (for more about concept cars and concept services, see Chapter 4). So, create an infusion plan and make sure it contains plenty of emotional and symbolic aspects. These are, after all, the changes you want to see in the organization.

Empowerment

The symbolic story of the Nordstrøm employee handbook has created a myth inside and outside of the organization that encapsulates the customer service culture at Nordstrøm. The handbook, which all new employees receive, is simply a postcard that says:

Our number one goal is to provide outstanding customer service. Our employee handbook is very simple. We have only one rule: use good judgement in all situations.

It is symbolic because it says a lot more to employees than the literal words convey, and it is mythical because, although true, it is only part of the story. Nordstrøm actually has a detailed employee handbook with guidelines for many aspects of behavior, such as its social media policy.

Empowerment refers to both the transfer of authority downwards in the organization and the recognition of someone’s ability to act, and to act in the right way, as a situation requires. This recognition increases an employee’s responsibility and can be a strong motivator for them. Implicit in empowerment is trust in the employee to do the right thing for the good of the customer and company, and a symbolic message of shared responsibility.

At some point in your transformational journey, you will encounter situations where you have to decide between scripting the experience and empowering your frontline employees to do the right thing. This is not an either/or option, and a combination of scripting and empowerment can work well. McDonald’s is a highly scripted organization that delivers a consistent experience around the world, and the experience it offers maintains its established market position. However, the strict focus on scripting leaves employees vulnerable and often reduces the quality of the experiential delivery, because unexpected situations occur all the time and require people to go off-script. If the employees are strictly taught to follow a script, and have tightly defined roles, then their freedom to be spontaneous is seriously limited—and the experience will suffer for it.

Empowering Production Workers at a Manufacturing Plant

There is a difference between American and Scandinavian approaches: the American approach tends to be more tightly scripted and hierarchical, while the Scandinavian approach is less scripted and has a flatter organization. There are multiple reasons for this, and I advocate a combination—a script and the empowerment to deliver on the desired experience. If the employees know and understand the experience that customers should receive, they will be joining the company because of it, they will be naturally able to deliver it, and they will be better able to make the multiple small adaptations to the experiential journey that are needed to make it successful.

Removing Silos

In a recent survey from the American Management Association, 83% of executives said that silos existed in their companies and 97% thought they have a negative effect.5

Silos breed mini-fiefdoms within the organization, making people less likely to collaborate, share information, and work together as a cohesive team. Indeed, silos encourage competition and division (interestingly, they are often called divisions) instead of collaboration. Silos are a consequence of value chain thinking, rather than value network thinking, and they force the customer to navigate their way across your organization, rather than you helping them along their journey. Further, KPIs for silos usually encourage within-silo results, rather than cross-silo collaboration. It is rare to see a KPI based on the latter.

Channel silos have historically popped up to cope with a new technology (e.g., internet, social media). But customers usually want to freely move between channels, and this can cause problems. Managing the experience across touchpoints then becomes a challenge since you are also managing across silos, again bringing in all of the disadvantages of silos, and few of the advantages.

Not surprisingly, this leads to poor decision making, poor collaboration, and low morale, and it impacts the company’s efficiency and profitability. Often silos are developed based on a function that has its own field of knowledge (marketing, sales, etc.), and this can lead to rivalry and power struggles between groups. Customer don’t care about your silos, but they are often forced to navigate between them—so make it easier on the customers and remove them.

Mind the Gap: Using a Gap Analysis to Map Your Position

Determining the degree of change needed in your organization and choosing a transformation strategy to get there both require careful planning. A gap analysis is a valuable tool to help you identify how much change is necessary and plan the transition. Knowing the current situation and your desired future situation will make you better able to plan the transition. Chapter 4 is a good starting point for a gap analysis of how far you are from the key aspects and behaviors of an experience-centric organization. Go through the list, and honestly ask yourself if you exhibit these behaviors partly, mostly, or totally. Then combine your results with your position on the five-step experience-centric organization trajectory (Chapter 2), and you will have a good starting point for your organizational journey. This journey may start with a short sprint, but parts will always be a marathon, and you need to be prepared for this.

Your change strategy will depend on your starting point and the gap you have to bridge. As with all organizational change, it is wise to plan, to not rush into radical change, and to pace your transformation. However, each organization is unique, so there is no universal approach here.

Measuring Progress: What Can’t Be Measured Can Be Managed

Although metrics can be important management tools, there is a danger of overreliance on them, to the detriment of good judgment. Research contains many examples of incentives that reduce effort or motivation, much of which goes back to the idea of the rational human being (see Chapter 6) with a focus on a quantitative approach to leadership. In The Tyranny of Metrics (Princeton University Press) author and historian Jerry Muller explains how we became reliant on measures, and he highlights examples of overreliance on data. Muller’s main finding is that what can and does get measured is not always worth measuring, may not be what we really want to know, and may take focus away from the things we really care about. The main message in his book is that “measurement is not an alternative to judgment: measurement demands judgment.” In other words: data isn’t always better, but thoughtful reflection always is.

The focus on design thinking in organizations has led to several requests to develop KPIs in that area. In one project, we conducted a thorough analysis of design thinking research and identified 17 core traits of design thinking. We then set about developing KPIs for these, all the while being aware of how KPIs can be used at the enterprise level, for business units, for individual departments, and at the employee level. What we found is that design thinking is not easily quantified in itself, and that many aspects of it do not lend themselves to outcome-related measures. For example, design thinking is visual in nature, and although it is possible to measure visual production, the measure would have little value. Another example is that design thinking is reflective and involves reframing a question—to look at it from a broader perspective and really understand the problem—before trying to solve it. Again, this is very difficult to quantify, but is something that you can gauge from subjective monitoring. This does not make these aspects unimportant, but rather a part of your organizational logics requiring subjective evaluation.

We also discovered that some aspects of design thinking can be measured as outcomes, some can be measured in terms of completed stages of development, and some can be measured in terms of process conformance. Others cannot be measured at all, at least not in any directly meaningful way, such as customer empathy at organizational level. Although not measurable, this is an important organizational behavioral trait.

KPIs can be critical for goal setting and performance management, for benchmarking, and for increasing motivation to achieve specific targets, but they have to be balanced with reflection and subjective views; you should be able to reflectively feel how things are going, rather than looking at numbers to determine this. The contact with customers, the reviews online, and the cultural comments about your organization will all contribute to this. Rather than taking the rational economic approach, we encourage listening, analysis, and reflection as key skills for the experience-centric organization. No, don’t throw away numbers, but do allow for qualitative values and reflective analysis.

Prototyping the Organization

One of the core behaviors of design is to prototype, and there is often a misunderstanding about why designers prototype. Many people believe that a design prototype is a nearly finished version of a product or service as a final sign-off before production. While this is one type of prototype, the goal of prototyping is to gain a better understanding of the problem. When you try something in a quick-and-dirty way, it is highly likely to fail, but that failure gives you insight into why it failed and can produce a breakthrough in understanding the problem. As mentioned in Chapter 4, this is termed failing forward and fast—that is, failing with intent to understand.

The same approach should be applied to an organizational design process. It is rare to get an organizational design right the first time around, and it can take some time to fine-tune one when it is in place. Is it possible to prototype an organization? Can you evaluate the value of an organizational change, before implementing it? Answering these questions is not straightforward, and introduces some maybes into the conversation. Since all service innovations have an element of organization in them, some degree of organizational prototyping will be needed. However, large-scale organizational change is difficult to prototype, and I haven’t seen examples of this being carried out (other than through small-scale trials of something that might be scaled). The area of organizational prototyping, while important, is one that is still new and needs further development.

Integrating Design Thinking and Design Doing into Your Organization

One central message of this book, is that design is key to your development. But when I say design, I don’t mean just any kind of design. I want you to hire designers, because this will give you the competencies necessary for your transformation. But you need to be critical about what kinds of designers you use, because in my experience all kinds of people use the term design thinking, but they don’t always have the right skill set to help your transition in an experiential way. All people who design want to make things better, but the types of designers I want you to connect with are usually (but not always) those who have been to design school. They are visual, have user empathy, and have a history of combining aesthetics, function, and materials (including technology). My experience is that a new brand of designer, the service designer, with a background in a creative design discipline is good at this, but you will find fantastic industrial designers, graphic designers, and interaction designers who can help you.

Be Less the Rock Star, More the Facilitator of Co-Design Processes

Design has changed during the past few decades, moving away from the image of the rock star product designer who took a brief, then went into their black box only to finally pull a rabbit out of a top hat with some amazing designs. Today, designers are trained to be facilitators and collaborative co-designers, working with other disciplines (and customers) to develop solutions together. This approach is necessary to be able to design for experiences that have consequences all the way around the wheel of experience centricity. But design is about much more than facilitating processes. It is also a highly experiential discipline, both taking inspiration from other experiences and being able to create them. Being able to both think and do experientially is a critical design skill.

Finding the right design match for your organization requires knowing your experiential DNA well. This is why I suggest that your first contact with designers is through an external design consultancy as part of the five-step path to experience centricity. Bring designers in at the journey phase, and get a feel for the right designers for your organization. Designers need to have a personality that fits your organizational DNA and the ability to co-design with others.

Develop DesignOps Within Your Organization

One of the key aspects of design that is not always understood is that design is preoccupied with method. DesignOps, short for Design Operations, is the organizational unit that plans, defines, and manages the design process within an organization. You should develop a DesignOps team in your organization that is cross-disciplinary and reports to the CXO.

While the term DesignOps is recent, a similar role has existed for a while. It is an evolution of process management, with the recognition of the experiential aspect that design brings. DesignOps has become a popular term now, because design teams are growing and there is an increasing need to focus on unifying the design approaches within an organization. The DesignOps manager is not necessarily a designer, and the team will most likely comprise different disciplines. What is common to all members of DesignOps is their focus on using methods to support the organization’s experiential vision. Thus, they have an operational role but an evangelical role too, and can be central in the infusion of customer experience within the organization.

Interview with Olof Schybergson

As CEO of Fjord, Olof Schybergson knows a lot about digital transformation. Fjord is a part of Accenture Interactive, and now has over a thousand designers spread over 27 offices. This makes them one of the largest design and innovation consultancies in the world. Olof believes strongly in design as a strategic resource and argues here for its role in the transformation of whole industries.

Q: Talk about transformation toward experience centricity.

A: I think one of the meta-challenges of many CEOs is about how to reorient the business to be more experience-centric and how to move from the industrial calcified model to a flexible and fluid agile living business.

It’s pretty much impossible to take the old model and replace it with the new model overnight. So it’s not just about staying in the old and ignoring the new or also jumping to the new. It’s rather a careful or wise pivot. The pivot is to a living business that is adaptable, scalable, and fluid. It is needed because the everyday way of generating value is being challenged and needs to be reinvented. The wise pivot is where you maximize efficiency to free up capacity to invest in the new, which you build gradually. Then you move the old core into the new. It’s not a wholesale shift it’s a gradual increased investment and focus on the new.

“Triggers vary, but often the important questions are quite existential, like ‘How can I create an experience that is best of class?’ ‘Who are my customers tomorrow?’ ‘What business am I in?’ and ‘What business should I be in?’”

Q: What are the tripwires along the transformation journey?

A: It is a great challenge to free up mindshare and organizational leadership capability to be able to focus on the new. This is especially true when the new is very small. There is a key calibration question about how much you can invest in the new before it becomes a meaningful business.

Tradition can be a problem. Organizations that have worked in one way are often ill-equipped to build new ways of working, especially ones that might cannibalize their existing business. So this can lead to a kind of organ rejection. You have to be prepared to face some headwinds and to challenge your own way of thinking, your traditional talent model, and so on. If you pull the plug on your new business too quickly, you will lose out. If you are not prepared to meet headwinds, then you are in danger.

Transformation toward experience centricity is a C-level responsibility. Lack of C-level and CEO-level sponsorship is a major tripwire. Transformations such as these are a major changes in the way that an organization thinks and acts, and should not be placed down in the organization. They have to be led from the top.

Q: How do you see the role of design in this transformation?

A: We are increasingly seeing design being used to create a strategic compass for the company. Triggers vary, but often the important questions are quite existential, like “How can I create an experience that is best of class?” “Who are my customers tomorrow?” “What business am I in?” and “What business should I be in?” Design helps ask, explore, and answer these questions.

Design is essential to make sense of the [qualitative] and [quantitative] data to make things meaningful and actionable. The fusion of data and design is important.

There can be an inability to mobilize around design—an inability to know where to start and how to get off the ground when going across different business units. Many realize that it is important. It is less about resistance and more about activation.

Endnotes

1 Teresa M. Amabile, “Motivating Creativity in Organizations: On Doing What You Love and Loving What You Do,” California Management Review, 40, no. 1 (1997).

2 Flow is a concept that describes the feeling of being immersed in a task to the extent that time and place disappear. It is described well in Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 1990).

3 The concept of organizational logics is derived from institutional logics, which describe how an institution develops belief structures that influence its behaviors and decision making. See Patricia H. Thornton and William Ocasio,“Institutional Logics,” in Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, ed. Royston Greenwood et al. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008).

4 “United Breaks Guitars” was a song and an early viral video hit by the musician Dave Carroll, written after an experience where his guitar was broken by a baggage handler on a United Airlines flight in 2008. It is often used as an early example of customer empowerment through social media.

5 “America Management Association Critical Skills Survey,” amanet.org. The survey was published in 2016, but is no longer available online.