CHAPTER 13

Balance the Trade‐Off Among Cost, Schedule, and Scope

INTRODUCTION

As I prepared to write this chapter I received an e‐mail that ended this way:

I have recently changed job focus. I work part‐time from home while caring for my six‐week‐old girl. Parenthood has consumed more of my personal resources than I budgeted. Consequently, I am behind schedule on this project.

This new father is not only learning about the demands of parenthood, he has aptly summed up a dilemma of life: limited resources. Whatever we do, we are faced with limited time, limited money, and a shortage of the people, equipment, and materials we need to complete our jobs. This problem of limited resources goes beyond issues of efficiency or productivity. No matter how efficient they may be, new parents and project managers alike must realize their limits and make choices.

But doesn't good project management mean we get more done, in less time, for less money? This is a valid question. Good project management does deliver more for less (particularly when compared to bad project management). But there are still limits. The best predictor of project success remains realistic stakeholder expectations. The project manager needs to rein in any unreasonable demands by the customer, as well as any unreasonable hopes of the project team. If these hopes and demands are allowed to drive a project, the result will almost certainly be cost and schedule overruns—and painful disappointment later in the project. Instead, project managers must establish realistic expectations through rational analysis of the facts. They must employ the definition and planning techniques described in previous chapters to balance the project scope against these three most common project constraints:

- Time. The project, as defined, won't be finished in the time originally envisioned in the project rules.

- Money. The project can deliver the desired outcome on schedule, but the cost is too high.

- Resources. The projected cost is acceptable, but the schedule calls for people, equipment, or materials that aren't available. You could afford them, but there aren't any to hire.

If one or more of these constraints is a factor, the project will need to be balanced; that is, the balance among the cost, schedule, and scope of the product will have to be reconsidered. This balancing can take place at several different levels.

THREE LEVELS OF BALANCING A PROJECT

Balancing a project can take place at one of three different levels of authority in an organization, depending on the kind of change needed:

- Project. Balancing at the project level requires making changes that keep the project on track for its original cost, schedule, and scope objectives. Since these three parts of the project equilibrium won't change, the project manager and team should have authority to make these decisions.

- Business case. If the project cannot achieve its cost‐schedule‐scope goals, then the equilibrium among these three factors must be reexamined. This means that the business case for the project must be reevaluated. Changing any of the goals of the project puts this decision beyond the authority of the project manager and team. To understand why the decision to change the cost‐schedule‐scope equilibrium has to be made at the business level, consider that:

- Cost goals are related to profitability goals. Raising cost targets for the project means reevaluating the profit goals.

- Schedules are closely linked to the business case. Projects that deliver late often incur some profit penalty, through either missed opportunities or actual monetary penalties spelled out in the contract.

- Changing the features and performance level of the product affects the value of the end product.

- Balancing the project to the business case requires agreement from all the stakeholders, but most of all from those who will be affected by changes to cost, schedule, or scope.

- Enterprise. When the project and business case balance, but the firm has to choose which projects to pursue, it is then balancing the project at the enterprise level. The enterprise could be a department within a firm, an entire company, or a government agency. This decision is absolutely beyond the power of the project manager and team, and it may even exceed the authority of the sponsor and the functional managers, although they'll be active participants in the decision. Choosing which projects to pursue and how to spread limited resources over multiple projects is primarily a business management decision, even though it requires project management information.

BALANCING AT THE PROJECT LEVEL

There are as many ways to balance projects as there are projects. This chapter presents the best‐known alternatives for balancing at the project, business case, and enterprise levels. Because determining the right alternative depends on which balance problem exists, each alternative is listed with its positive and negative impacts and the best application—the best way of applying the technique. Following are a number of ways of balancing the project at the project level.

1. Reestimate the Project

This is the “optimist's choice.” This involves checking your original assumptions in the project charter and the work package estimates. Perhaps your growing knowledge of the project will allow you to reduce your pessimistic estimates. Here are the possible impacts of this kind of checking:

Positive. If certain estimates can be legitimately reduced, the project cost, and perhaps the schedule estimates, will shrink, and the accuracy of your estimates will have increased.

Negative. Unless there is new information to justify better estimates, don't fall prey to wishful thinking.

Best application. Always check your estimates. Make sure your estimating assumptions about productivity, availability of skilled people, and complexity of tasks are consistent and match all available information. While you are making changes, however, it's important not to succumb to pressure and reduce the estimates just to please management or customers. If anything, the second round of estimating should create an even firmer foundation of facts supporting cost, schedule, and resource estimates.

2. Add People to the Project

This is an obvious way to balance a project because it reduces the schedule. Adding people to the project team can either increase the number of tasks that can be done at the same time or increase the number of people working on each task.

Positive. The schedule is reduced because more labor is applied every day of the project.

Negative. Fred Brooks1 summed up the danger of this alternative in the title of his landmark book, The Mythical Man‐Month. Pouring more people onto the project may reduce the schedule, but it increases the cost of coordination and communication. Economists refer to this effect as the law of diminishing marginal returns.

You can't just add another warm body to a project; this option requires qualified resources. Many project managers have asked for more people, only to have the most available people (which usually means the least competent) sent to their projects. Weighing the project down with unskilled workers can create such a drag on productivity that it is almost certain to drive up both cost and schedule.

Best application. Certain work lends itself to piling on, that is, adding more people to get the job done faster. Task independence and product development strategy are both factors to consider when adding people to a project. The greater the independence of the concurrent tasks, the more constant the advantage of adding people.

For instance, a highway department plans on repaving a 100‐mile stretch of highway. They could break down the repaving into 10 10‐mile subprojects and perform them all at the same time, assuming they had enough qualified contractors to run 10 projects concurrently. (If shortening the schedule were really important and there were enough road paving contractors, they could even break it into 20 5‐mile subprojects.) The independence among all the subprojects makes it possible to overlap them. Trying to coordinate that many people and that much equipment would require extra project management effort, but even if it took 10 times as many supervisors from the highway department to coordinate the project, these costs would remain constant because the duration would be cut by 90 percent. There are other realities to consider on a project like this, however, such as whether all the various contractors will use the same roads, gravel pits, and equipment parking. But these are only resource constraints (resource constraints can be analyzed using the resource‐leveling technique described in Chapter 10).

Fred Brooks also points out that a software development schedule is not strictly divisible by the number of people on the project. But developing software products can require huge teams. Likewise, producing a new commercial aircraft requires thousands of engineers. Projects that use knowledge workers can usefully add people to reduce their schedules by following good product development practices such as these:

- The project team organization reflects the product design. The overall project must be broken into teams and/or subprojects the same way the overall product is broken into components or subproducts. Manufacturing companies refer to this organizational style as integrated product teams (IPTs), because all of the disciplines required to develop a component of the product are teamed together.

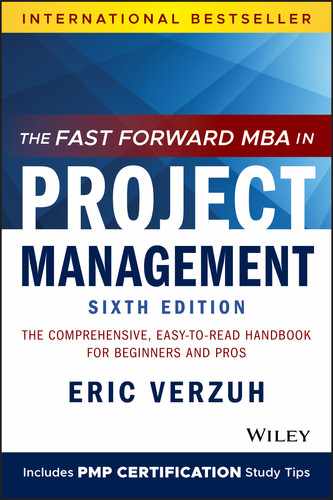

- The product is designed from the top down, and the schedule contains design synchronization points. Top‐down design means establishing the product's overall design parameters first, then repeatedly breaking the product into components and subcomponents. Scheduled synchronization points are times to focus on component interfaces and reevaluate how the entire product is meeting the overall product design requirements (see Figure 13.1).

- Actual construction of any part of the product begins only after the design for that component has been synchronized and stabilized against the design for interfacing components. Aircraft manufacturers commonly use three‐dimensional engineering software that actually models the interaction of different components, eliminating the need for physical mock‐ups of the aircraft. Figure 13.1 demonstrates how useful a network diagram is for identifying concurrent tasks. These concurrent tasks are opportunities for adding people to the project in order to reduce overall duration.

FIGURE 13.1 Top‐down design and design synchronization points.

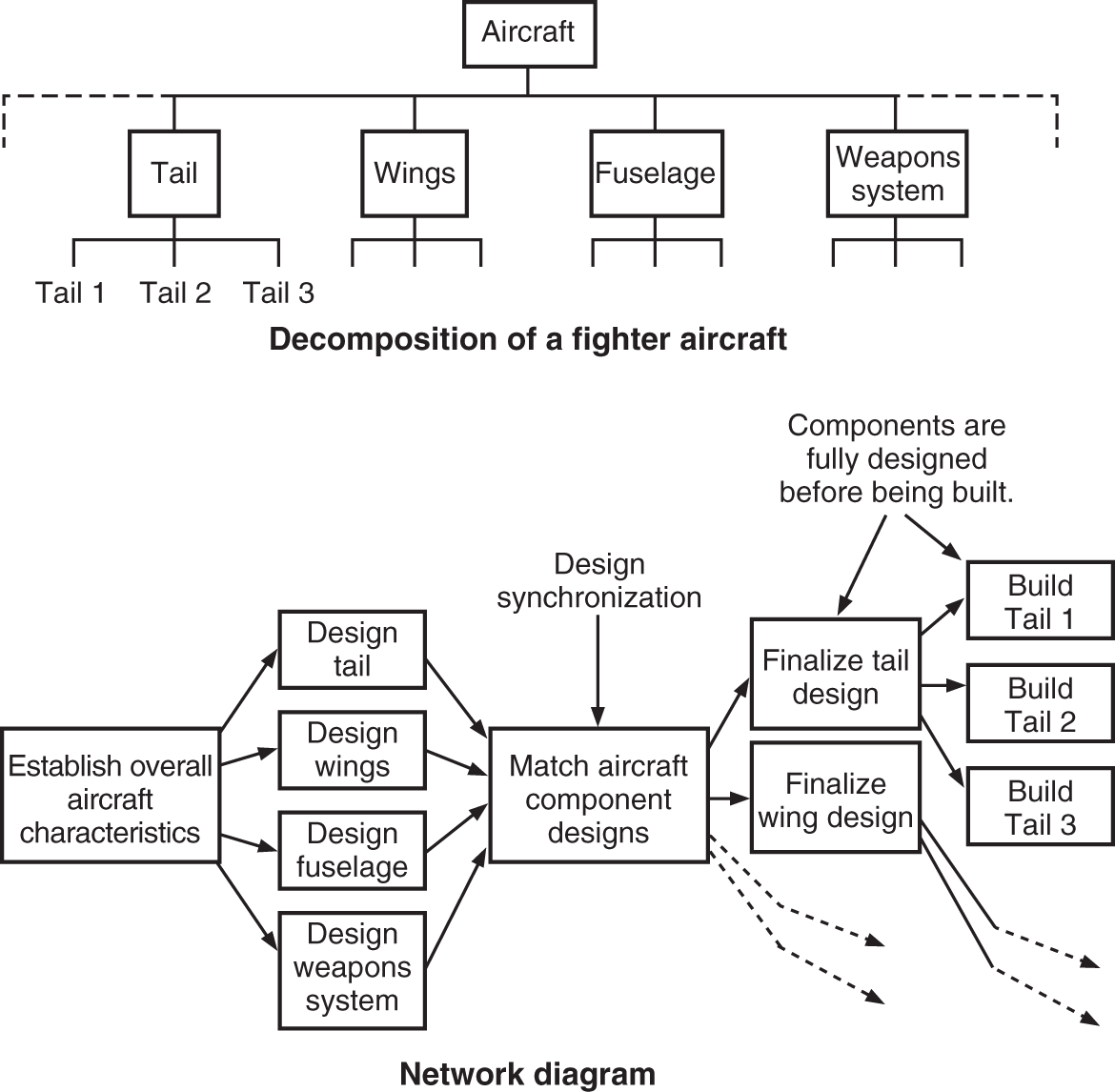

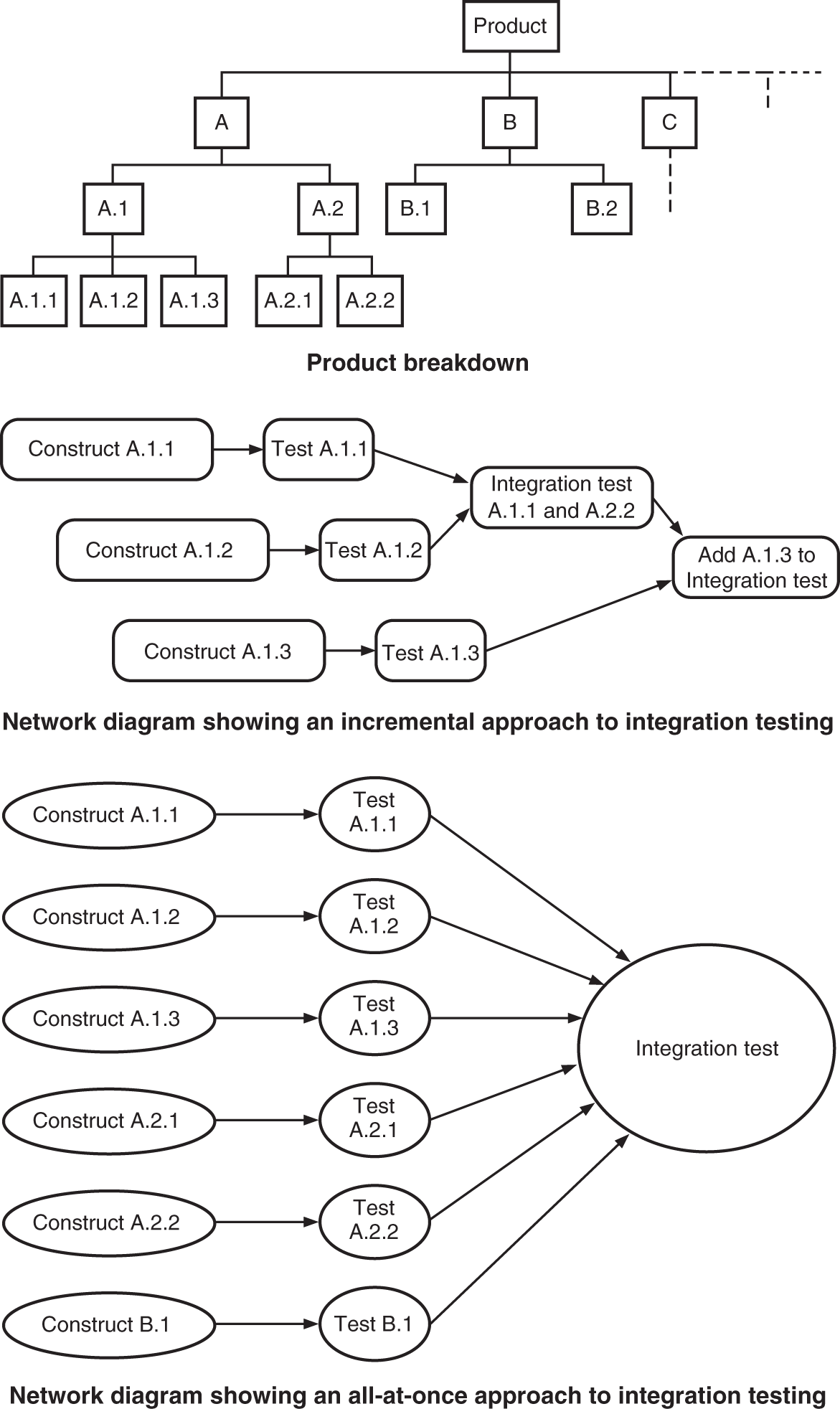

- Component construction includes unit testing and frequent integration testing. Unit tests refer to testing the functions of individual components as they are built. Frequent integration tests pull together the most up‐to‐date versions of completed components to make sure they work together. Frequent integration testing has emerged as a required development technique for products with many components because the sheer number of possible interface failures is beyond the ability to test and effectively debug (see Figure 13.2).

Finally, don't forget that by adding people to the project to reduce schedule, you are increasing cost risks. The more people who are idled by unexpected delays, the higher the cost per day of any delay.

FIGURE 13.2 Component construction phase includes frequent unit and integration tests.

3. Increase Productivity by Using Experts from Within the Firm

It's no secret that some people are more productive than others. I've seen top computer programmers turn out 10 times as much as the weakest member of a team. Though it may not be at a 10:1 ratio, every industry has people who are just more capable. So why not put as many of them as you can on your project? These high performers have technical competence, problem‐solving skills, and positive attitudes. After they've reestimated your project, it will probably meet or beat all the original assumptions about cost and schedule performance.

Positive. Not only will this team deliver the best possible schedule performance, it will also be cost‐effective. These high performers might double the output of the average team member, but it's rare that they get paid twice as much for doing it. On top of that, their expertise is likely to produce a better product.

Negative. This can be an inefficient strategy for the firm. Putting all these stars on one project means that they'll probably be doing work that's well below their ability levels—something a junior staff member could do as well, even if not as fast. Another negative is that when other projects begin to suffer, the stars will be reassigned and the stellar project will slowly fall behind schedule.

Best application. Top people are spread around many projects so their ability and expertise can make other people more productive. You'll have a better chance of getting the optimal mix of average and star players when you do two things.

First, create experts within the team by putting the same people on related tasks. For instance, when a team of business analysts was working with a hospital to redesign the hospital's methods for keeping records of patients, the project leader assigned one person to be responsible for decisions affecting the maternity ward, another for the pediatric ward, another for the pharmacy, and so on. Even though these assignments didn't necessarily increase their skill level as analysts, each person did become the subject matter expert for their part of the project. This strategy is even more important when there are many people who won't be working full‐time on the project, because it keeps specialized knowledge in one place.

Second, using the work breakdown structure, network diagram, and work package estimates, identify the tasks that benefit most from top talent. Here are some indicators that you'll get a big payback from a star:

- Cost. The most complex tasks produce the highest returns from top performers. These are the kind of tasks that produce productivity ratios of 10:1.

- Schedule. Put the top performers on critical path tasks, where their speed will translate to a shorter overall project schedule.

- Quality. Top performers make good technical leads by making major design decisions and spending time discussing work with junior team members.

Most important, involve top performers in project management activities such as risk management, estimating, and effective assignment of personnel.

4. Increase Productivity by Using Experts from Outside the Firm

The same logic for the preceding alternative applies here, except that this option seeks to pull in the best people from outside the firm. Whether you hire individual people as contract labor or engage a firm to perform specialized tasks, the process is similar: Use the work breakdown structure to identify the best application of their talents and manage them like one of the team.

Positive. Some work is so specialized that it doesn't pay to have qualified people on staff do it. The additional costs incurred by hiring the outside experts will be more than offset by the speed and quality of their work. Just as with the experts from within the firm, assign them the time‐ or quality‐critical tasks to get the most leverage from their work.

Negative. There are two downsides to this option: vendor risk and lost expertise:

- Vendor risk. Bringing an outsider into the project introduces additional uncertainty. Unfortunately, not every expert delivers; he or she may not live up to the promises. By the time you find out your expert isn't productive, you may find, in spite of the added costs, that the project is behind schedule. In addition, locating a qualified vendor or contract employee can be time‐consuming; if it takes too much time, it can become a bottleneck in the schedule.

- Lost expertise. Every contract laborer or subcontractor who walks out the door at the end of the project takes some knowledge along—and this problem intensifies if the work is “brain work.” In this case, the project manager needs to make sure that the work has been properly recorded and documented.

Best application. Hiring outside experts is useful when it appears that their specialized skills will move the project along faster. You should expect these experts to attend team meetings and participate in product development discussions; don't let them become islands, working alone and avoiding interaction with long‐term employees. Like the inside experts, they should be included in project management and other high‐leverage activities. Before they leave the project, whatever they produce should be tested and documented.

The added productivity that outside resources bring to the project must outweigh the effort to find and hire them. The ideal situation is to have a long‐term relationship with a special‐services firm whose employees have demonstrated their expertise on past projects.

5. Outsource the Entire Project or a Significant Portion of It

This method of balancing a project involves carving out a portion of the project and handing it to an external firm to manage and complete. This option is especially attractive if this portion of the project requires specialized skills not possessed by internal workers.

Positive. This moves a large portion of the work to experts whose skills should result in greater productivity and a shortened schedule.

Negative. This shifting of responsibility creates more risk. The project manager will have less control over the progress of the work, and if the outside specialists prove to be less than competent, it may be too late to “switch horses.” Even if it succeeds, an outside firm will leave little of its expertise with your firm at the end of the project.

Best application. Outsourcing is at the high end of the risk/return spectrum. When it works, it can be a miracle of modern business methods; when it doesn't, it can result in real catastrophes. The keys to successful outsourcing are finding qualified vendors and coming to clear agreements before the work begins. These agreements must be built using various tools from this book, including responsibility matrixes, work breakdown structures, network diagrams, and Gantt charts.

Don't Underestimate the Risks of Outsourcing

Don't Underestimate the Risks of Outsourcing

The full process for finding and hiring a qualified subcontractor involves many of the techniques in this book—and even more that you won't find here. Finding qualified subcontractors for large projects amounts to a major subproject in itself. Don't underestimate the risks and challenges of outsourcing major projects.

6. Work Overtime

The easiest way to add more labor to a project is not to add more people, but to increase the daily hours of the people already on the project. If a team works 60 hours a week instead of 40, it might accomplish 50 percent more.

Positive. Having the same people work more hours avoids the additional costs of coordination and communication encountered when people are added. Another advantage is that during overtime hours, whether they come before or after normal working hours, there are fewer distractions in the workplace.

Negative. Overtime costs more. Hourly workers typically earn 50 percent more when working overtime. When salaried workers put in overtime, it may not cost the project more money, but sustained overtime can incur other, intangible costs. In their book Peopleware: Productive Projects and Teams, Tom DeMarco and Timothy Lister not only recognize the intangible cost of sustained overtime (divorce, burnout, turnover), they also call into question whether any overtime on projects involving knowledge workers is effective. They state, “Nobody can really work much more than forty hours [per week], at least not continually and with the intensity required for creative work… . Throughout the effort there will be more or less an hour of undertime for every hour of overtime,” where undertime is described as nonwork activities such as “personal phone calls, bull sessions, and just resting.”2 Adding in overtime assumes that people are as productive during the ninth, tenth, and eleventh hours as they were the first eight hours of a day. Since this is rarely the case for any type of worker in any industry, the extra pay and intangible costs of overtime may not really buy much in increased output.

Best application. How much overtime is effective is debatable, but one thing is certain: Overtime is perceived by the project team as over and above the normal expected performance. Whether he or she demands overtime or allows people to voluntarily sign up for it, the project manager must demonstrate clearly the ways in which the extra work will benefit the project and the individual team members. The best rule is to apply overtime sparingly and only where it produces big paybacks.

Reducing Product Performance Is Not an Option

Reducing Product Performance Is Not an Option

As stated in Chapter 3, the two characteristics of product scope are functionality and performance. Functionality describes what the product does, while performance describes how well the functionality works. Reducing the performance of the product is another way of balancing a project. Time and money can be saved by cutting the testing and quality control tasks and by performing other tasks more quickly and less thoroughly.

Positive. The cost and schedule may very well be reduced because we're spending less effort on the project.

Negative. Philip Crosby3 titled his book Quality Is Free on the premise that the cost of doing things twice is far greater than the cost of doing them right the first time. When performance is cut, costs go up for many reasons, including these:

- Rework (performing the same tasks twice because they weren't done right the first time) during the project will drive the cost higher and delay completion.

- Rework after the project finishes is even more expensive than rework during the project. Any potential development cost savings are wiped out by the high cost of fixing the product.

- Failures due to poor product performance can be staggeringly expensive. Product recalls always bear the expense of contacting the consumers as well as fixing or replacing the product. Product failures such as collapsing bridges and malfunctioning medical equipment can even cost lives.

- Poor product performance causes damage to the reputation of the firm and ultimately reduces the demand for its product.

Best application. Never! Crosby's argument is correct: It is cheaper to do it right than to do it twice. The only legitimate arguments in favor of cutting performance are presented in the next section under the first alternative, “Reduce the Product Scope.” (Read more about managing quality in Chapter 23.)

7. Crash the Schedule

![]() Two scheduling methods for compressing the schedule are to switch resources to the critical path and to crash the critical path. These can be low‐cost and make you look smart because you really know your schedule. Both techniques are covered in the PMP® Exam Prep bonus video Compress the Schedule, which is found at www.VersatileCompany.com/FastForwardPM.

Two scheduling methods for compressing the schedule are to switch resources to the critical path and to crash the critical path. These can be low‐cost and make you look smart because you really know your schedule. Both techniques are covered in the PMP® Exam Prep bonus video Compress the Schedule, which is found at www.VersatileCompany.com/FastForwardPM.

BALANCING AT THE BUSINESS CASE LEVEL

If, in spite of all attempts to balance a project at the project level, the cost‐schedule‐scope goals still cannot be achieved, then the equilibrium of these three factors needs to be reexamined. This means that the business case for the project must be reevaluated. Decisions relating to goals are beyond the authority of the project manager and team alone; this reevaluation requires the authorization of all the stakeholders. This section will look at the various ways that the business case for a project can be reevaluated.

1. Reduce the Product Scope

If the goals of the project will take too long to accomplish or cost too much, the first step is to scale down the objectives—the product scope. The result of this alternative will be to reduce the functionality of the end product. Perhaps an aircraft will carry less weight, a software product will have fewer features, or a building will have fewer square feet or less expensive wood paneling. (Remember the difference between product scope and project scope: Product scope describes the functionality and performance of the product; project scope is all the work required to deliver the product scope.)

Positive. This will save the project while saving both time and money.

Negative. When a product's functionality is reduced, its value is reduced. If the airplane won't carry as much weight, will the customers still want it? If a software product has fewer features, will it stand up to competition? A smaller office building with less expensive wood paneling may not attract high‐enough rents to justify the project.

Best application. The key to reducing a product's scope without reducing its value is to reevaluate the true requirements for the business case. Many a product has been over budget because it was overbuilt. Therefore, reducing product scope so that the requirements are met more accurately actually improves the value of the product, because it is produced more quickly and for a lower cost.

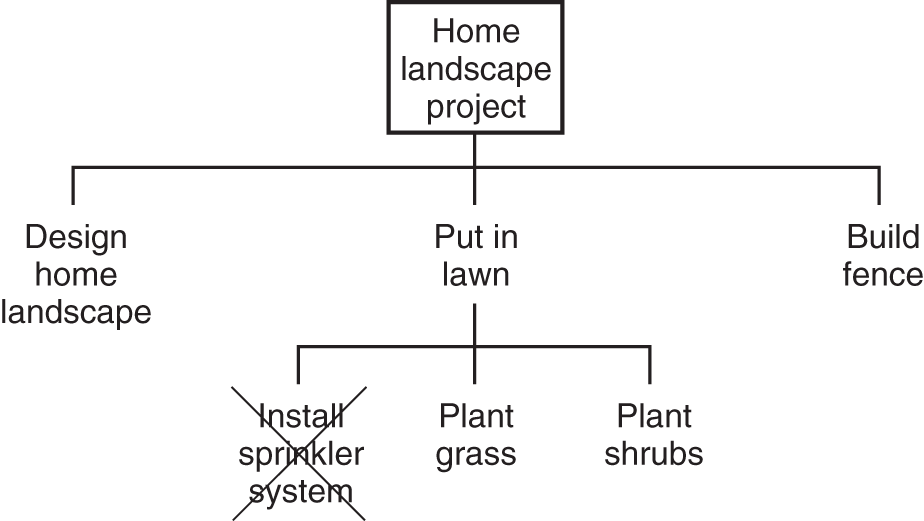

Calculating the cost and schedule savings of reduced functionality begins with the work breakdown structure. Reducing the functionality means that certain tasks can be reduced or eliminated; these tasks need to be found and the estimates reduced accordingly (see Figure 13.3). As always, focusing on critical path tasks is the surest way to reduce a schedule.

If the project remains over budget or over schedule after you have reevaluated the requirements and scaled back the product scope, then it is time to focus on the customer's use of the product. Which requirements are absolutely necessary and which could be modified or eliminated? You can start by prioritizing the requirements, then analyzing the cost‐benefit trade‐off of each requirement. In particular, expensive requirements that add little benefit need to be identified. Again, the first tool used in evaluating the cost and schedule savings of each requirement is the work breakdown structure.

FIGURE 13.3 Reduce cost or schedule by reducing project scope. The work breakdown structure is the basis for evaluating possible cost and schedule reductions to the home landscape project.

An Iterative Development Approach Prioritizes Requirements

![]() The agile methods described in Chapters 4 and 11 adjust the scope of the project to fit the time available. If your customer can get value from partial delivery of the product, this could be a good candidate for an agile approach.

The agile methods described in Chapters 4 and 11 adjust the scope of the project to fit the time available. If your customer can get value from partial delivery of the product, this could be a good candidate for an agile approach.

2. Fast‐Tracking

Fast‐tracking involves overlapping tasks that are traditionally done in sequence. The best example of this balancing technique is beginning construction on a building before the design is complete. The argument for fast‐tracking holds that you don't have to know where all the closets and doorways will be before you start digging the foundation.

Positive. Fast‐tracking can decrease the project schedule significantly, sometimes by as much as 40 percent.

Negative. Overlapping design and construction is risky, and this is why the decision to fast‐track a project must be made at the business level. All the stakeholders need to understand and accept the risk that, if initial design assumptions prove to be mistaken, part of the product will have to be demolished and built again. In the worst cases, the mistakes made in a fast‐track environment can not only slow down the project to the point where there is no schedule advantage, but can also cause the costs to run far over the estimates.

Best application. The fundamental assumptions of fast‐tracking are that only 15 to 30 percent of the total design work can provide a stable design framework and that the remainder of design activities can be performed faster than construction activities. For these assumptions to hold true, the product must be capable of modular, top‐down design. (This type of design was described in the previous section under alternative 2, “Add People to the Project.”)

Overlapping design and construction is becoming more common in software development, but in addition to overlapping these phases they also repeat each phase. Instead of increasing risk, this design‐build‐design‐build approach actually lowers risk, because the product is developed incrementally. Because of the incremental development, this doesn't quite qualify as a fast‐track example, but it does point up how this technique can be successfully modified.

The bottom line with fast‐tracking is that it overlaps tasks that have traditionally been done in sequence. The overlap is the risk. The Stellar Performer profile of Seattle Mariners Baseball Park at the end of this chapter demonstrates how risky it can be.

3. Phased Product Delivery

In a situation in which the project can't deliver the complete product by the deadline, there is still the possibility that it might deliver some useful part of it. Information systems composed of several subsystems, for example, will often implement one subsystem at a time. Tenants can move into some floors in a new office building while there is active construction on other floors, and sections of a new freeway are opened as they are completed rather than waiting for the entire freeway to be complete.

Positive. Phased delivery has several benefits:

- Something useful is delivered as soon as possible.

- Often, as in the case of information systems, phased delivery is actually preferred because the changes introduced by the new system happen a little at a time. This longer time frame can reduce the negative impacts to ongoing business operations.

- Feedback on the delivered product is used to improve the products still in development.

- By delivering over a longer period, the size of the project team can be reduced; a smaller team can lead to lower communication and coordination costs. And, since the people are working for a longer time on the project, project‐specific expertise grows. These factors should lead to increased productivity in subsequent project phases and to an overall lower cost for the project.

- Phased delivery allows for phased payment. By spreading the cost of the project over a longer time, a larger budget might be more feasible.

Negative. Not all products can be implemented a piece at a time. Phased implementation may also require parallel processes, in which old methods run concurrently with new methods, and this can temporarily lead to higher operating costs.

Best application. Modularized products, whose components can operate independently, can be delivered in phases. In order to determine how to phase a product delivery, you need to look for the core functionality—the part of the product that the other pieces rely on—and implement that first. The same criteria may be used in identifying the second and third most important components. When multiple components are equally good candidates, they can be prioritized according to business requirements.

Although consumer products such as automobiles don't appear to be good candidates for phased delivery (“You'll be getting the windshield in January and the bumpers should arrive in early March …”), a limited amount of phased delivery is possible for some consumer products. For example, software products can be upgraded cheaply and effectively over time by using the Internet, and current customers can download product updates directly onto their computers from company sites on the Internet.

4. Do It Twice—Quickly and Correctly

This method seems to contradict all the edicts about the cost advantages of doing it right the first time (as in Philip Crosby's book Quality Is Free). Instead, this alternative suggests that if you are in a hurry, try building a quick‐and‐dirty short‐term solution at first, then go back and build the right product the right way.

Positive. This method gets a product to the customer quickly. The secondary advantage is that what is learned on the first product may improve the second product.

Negative. Crosby is right: It is more expensive to build it twice.

Best application. This is an alternative to use when the demand for the product is intense and urgent—when every day (even every hour!) it isn't there is expensive. The high costs of doing it twice are more than compensated for by the reduced costs or increased profits that even an inferior product offers. Military examples abound, such as pontoon bridges that replace concrete bridges destroyed by combat. In the realm of business, a product that is first to market not only gains market share, but may actually provide the revenue stream that keeps the company alive to develop the next product.

5. Change the Profit Requirement

If your project needs to cost less in order to be competitively priced, this method recommends reducing the profit margin. This means reducing the mark‐ups on the project and the hourly rates charged for the project employees.

Positive. Costs are reduced while schedule and scope stay constant. Perhaps the lower cost helps the company win a big project. Even if the project isn't as profitable, it may give a good position to the firm in a new marketplace. Or it may be that a long‐term, lower‐profit engagement gives you the stability to take on other projects with higher returns.

Negative. The project may not bring in enough profit to allow the firm to survive.

Best application. Reducing the profit margin is clearly a strategic decision made by the owners or executives of the firm. This is a viable option when a firm must remain competitive in a difficult market. But deciding whether to go ahead with a project with a reduced profit margin would be considered an enterprise‐level decision for the firm bidding on the project.

BALANCING AT THE ENTERPRISE LEVEL

Enterprise‐level balancing mainly confronts the constraints of insufficient equipment, personnel, and budget. At the enterprise level, the firm decides which projects to pursue, given finite resources. Making these decisions requires accurate estimates of individual project resources, costs, and schedules (see the discussion on program management in Chapter 21).

Choosing between projects is difficult; there will always be important ones that don't make the cut. While it might be tempting to do them all, pursuing too many might be more costly than pursuing too few. When an organization tries to complete 10 projects with resources enough for only eight, it may wind up with 10 projects that are 80 percent complete. In spite of all the effort, it may not finish a single project.

The alternatives that are successful at the enterprise level are variations of the ones applied at the project and business case levels:

- Outsourcing allows you to pursue more projects with the same number of people, if you have enough money to pay the outside firm.

- Phased product delivery means that more projects can be run at the same time, with many small product deliveries rather than a few big ones.

- Reducing product scope on several projects requires cost‐benefit trade‐off analysis among projects, rather than just among functions on a single product.

- Using productivity tools can be a strategic decision to improve productivity across projects. The proper tools can bring great leaps in productivity increases; this may enable firms to pursue many more projects with the same number of people.

But no matter which alternatives the enterprise chooses or how successfully they are applied, there will always be more good ideas than time or money allows.

END POINT

END POINT

Balancing shouldn't wait until the end of the planning phase; it should be a part of every project definition and planning activity. Balancing involves reconsidering the balance among the cost, schedule, and scope of the product.

Although it is usually referred to as “course correction,” balancing will continue to be present during project control, as the team responds to the realities of project execution and finds that the original plan must be altered.

It would be a mistake to see project management techniques as a tool set for proving that schedules or cost requirements cannot be met. Rather, they're intended to make sure projects are performed the fastest, cheapest, and best way. Balancing requires stakeholders to face the facts about what is possible and what is not. When a project is badly out of balance, it will do no good to fire up the troops through motivational speeches or threats. People know when a job is impossible. Instead, the project manager's job is to create a vision of what is possible and then to rebalance the project in such a way that the vision can become a reality. Balancing requires thought, strategy, innovation, and honesty.

PMP Exam Prep Questions

PMP Exam Prep Questions

- The sponsor of a project is deciding whether the project should continue or be scrapped. The project has been plagued with issues. So far, $1M has been spent on the project. Of the following, what best describes the $1M that has been spent so far?

- Opportunity cost

- Budgeted cost of work performed

- Sunk cost

- Phase 1 cost

- The construction team is behind schedule on its project. The customer is considering giving the project to another company if the project cannot be put back on track. The team is considering putting more resources on the critical path to accelerate the schedule. This is an example of what?

- Staff acquisition

- Crashing

- Replanning

- Fast‐tracking

- The project to build an art museum for the city is in the planning stages. The project manager has determined that the installation of the marble water feature should be outsourced because his company does not have the necessary expertise. The vendor proposals specify different contract types: cost‐plus‐fixed‐fee, fixed‐price, cost‐plus‐incentive‐fee, and time and materials. Which of the proposals present the least probability of loss for the buyer?

- Proposals that use cost‐plus‐fixed‐fee

- Proposals that use time and materials

- Proposals that use cost‐plus‐incentive‐fee

- Proposals that use fixed‐price

Answers to these questions can be found at www.VersatileCompany.com/FastForwardPM.