Pooled investments

Instead of buying shares individually, investors can pool their money and buy shares (and other assets) collectively. There are some significant advantages of pooled (collective) investment.

First, a more diversified portfolio can be created. Investors with a relatively small sum to invest, say £3,000, would find it difficult to obtain a broad spread of investments without incurring high transaction costs. If, however, 10,000 people each put £3,000 into a fund there would be £30 million available to invest in a wide range of securities. A large fund like this can buy in large quantities, say £100,000 at a time, reducing dealing and administrative costs per pound invested. Thus risk is reduced by diversification and costs are reduced by economies of scale in share dealing and administration, such as time spent managing the portfolio.

Second, even very small investors can take part in the stock market. If you have only £50 per month to invest it is possible to gain exposure to the equity market by investing through pooled funds. Unit trusts, for example, are often willing to sign you up for a drip feed approach to investing in the markets.

Third, you can take advantage of professional management. You can avoid the demanding tasks of analysing and selecting shares and bonds, going into the market place to buy and collecting dividends and so on by handing the whole process over to professional fund managers.

Finally, you can enter exotic markets that would otherwise be beyond your reach. Perhaps you wish to invest in South American companies, US hi-tech or some other category of far-flung financial securities, but consider the risk and the complexities of buying shares direct too great. Collective funds run by managers familiar with the relevant country or sector can be a good alternative to going it alone.

These advantages are considerable but they can often be outweighed by the disadvantages of pooled funds, including high costs of fund management and underperformance compared with the market index. You will also lose any rights that accompany direct share investment, including the right to attend the company’s AGM or receive shareholder perks. And you lose the fun of selecting your own shares with its emotional highs and lows, triumphs and lessons in humility.

Unit trusts

With unit trusts the securities purchased by the investor are called ‘units’. The value of these units is determined by the market valuation of the securities owned by the fund. So, if, for example, the fund collected together £1 million from hundreds of small investors and issued 1 million units in return, each unit would be worth £1. If the fund managers over the next year invest the pooled fund in shares which rise in value to £1.5 million the value of each unit rises to £1.50.

Unit trusts are ‘open-ended’ funds, which means that the size of the fund and the number of units depend on the amount investors wish to put into the fund. If a fund of 1 million units suddenly doubled in size because of an inflow of investor funds (not because the underlying investments rise in value), it would become a fund of 2 million units through the creation and sale of more units.

If the example trust with 1 million units attracts a lot of interest because of its great first year performance (say the underlying shares have risen 50 per cent), it might then sell an additional million units at £1.50 each to become a fund with total assets of £3 million.

Unit holders sell units back to the managers of the unit trust if they want to liquidate their holding (turn it into cash). The manager would then either sell the units to other investors or, if that is not possible because of low demand, sell some of the underlying investments to raise cash to redeem the units. Thus, the number of units can change daily, or at least every few days.

Pricing

The pricing of unit trusts is not quite as simple as described above. In fact, the units generally have two prices. The total value of the investments underlying the fund is usually calculated once a day using a method prescribed by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). From this value the price a new investor has to pay to buy – the offer price – is calculated. The offer price is the price the trust would have to pay to purchase the investments currently held plus dealing costs, administration expenses and other charges. The total sum is divided by the number of units in issue.

The bid price (the price you can get if you want to sell) is usually set at 3–6 per cent below the offer price (for funds invested in shares). The spread, or front-end load, between the bid and offer prices pays for two things. First, fund administration, management and marketing. And second, the market makers’ spreads, stamp duty and brokers’ commissions payable by the fund when it buys and sells shares (bonds, etc).1

Most unit trusts are priced on a forward basis, which means that the price paid by a buyer of units will be fixed at a particular time of the day (often 12.00 noon) that is yet to come. So when you make out an order to buy you do not know what price you will pay, which is determined by what happens to the prices of the securities in the fund between now and the fixing price. Some funds still charge the historic price, taking the value from the last valuation.2

When judging the performance of a unit trust you must bear in mind the influence of the spread. For example, if the quoted prices for a unit move up from 200p–210p to 250p–262.5p the return (the difference between buying and selling price) is 250p–210p, which is merely 19 per cent, not 25 per cent. Clearly the bid–offer spread means that your fund has to work hard to produce good returns in the short term. One way of looking at this is: if you sign a cheque for £10,000 and the spread is 5 per cent, only £9,500 is left in the fund for you to draw out after one day.

Who looks after the unit holders’ interests?

There are four levels of protection for the unit holder:

- The trustee and auditor: The trustee, usually a bank or insurance company, keeps an eye on the fund managers to make sure they abide by the terms of the trust deed – for example, sticking to the stated investment objectives (e.g. investing in Japanese equities). Importantly, the trustee holds all the assets of the fund in their name on the unit holder’s behalf, so if anything untoward happens to the fund manager the funds are safeguarded. The trustee also oversees the unit price calculation and ensures the Financial Conduct Authority regulations are observed. The auditor checks that the accounts have been drawn up properly.

- The Financial Conduct Authority: The FCA authorises both the manager and the trustee to hold those roles. Only funds authorised by the FCA are allowed to advertise in the UK – these are Authorised Unit Trusts (AUTs). Unauthorised unit trusts, most of which are established offshore (outside the jurisdiction of the FCA) are available, but you should be aware that they carry more risk by virtue of their unregulated status.

- The Ombudsman: Complaints that have not been satisfactorily settled by the management company can be referred to the Financial Ombudsman Service (see Chapter 19) which can force compensation.

- The Financial Services Compensation Scheme: Up to £85,000 is available for a valid claim. For example, when an FCA authorised fund becomes insolvent or suffers from poor investment management (see Chapter 19).

Charges

There are many charges:

- Initial charge (‘sales’ or ‘front-end’ charge): This is included in the spread between the bid and offer prices. So if the fund has a spread of 6 per cent it might allocate 5 per cent as an initial charge. Some unit trusts have dropped initial charges to zero, particularly those investing in interest-bearing securities (bonds, etc) and tracker funds (see later).

- The Annual Management Charge (AMC): A typical actively managed fund charges between 0.65 per cent and 1 per cent, but can be higher. If you invest via a platform (see later) it may charge up to 0.45 per cent per year on top to hold your investments in your portfolio. If an independent financial adviser is organising the purchase for you, rather than a platform, you might have to pay a few hundred pounds in advice fees up front. The AMC is deducted from the fund on a daily basis, so you may not notice it being taken as the fund’s price is subtly adjusted downwards. Over time the annual fees have a larger effect in reducing the value of your investment than the initial charge.

- Ongoing charges: Further costs on top of the AMC are taken from the fund. When these are added to the AMC we arrive at the ongoing charges. The additional items include fees to the trustee, custodians (who hold the underlying securities), investment adviser (fund managers often get unit holders to pay for research on top of the AMC – yes, ‘experts’ hiring others to analyse, but not paying for it out of their pocket), fund valuers, marketers, accountants and auditors, regulators, insurers, lawyers, professional advisers and VAT on these charges. A charge of about 0.05–0.5 per cent per year generally covers these legal, audit and other administration costs. This is also deducted automatically by the fund manager on a daily basis. Ongoing charges (formally called total expense ratios) can be obtained for individual funds from markets: ft.com/data/funds/uk and www.bestinvest.co.uk.

- Various other deductions not included in the published ongoing charges: These include transaction costs associated with buying and selling securities such as brokers fees, bid/offer spreads on shares or bonds and transaction taxes such as stamp duty (0.5 per cent) in the UK. Don’t forget that you would incur these costs anyway if you were buying the shares directly – and without the benefit of the fund’s economies of scale. However, a fund with a high turnover in its portfolio (selling shares and replacing them with others) can pay out over 1 per cent per annum in additional costs. A more typical figure is less than this for active funds (probably around 0.4 per cent) and can be as low as 0.1 per cent for trackers.

Many commentators think that high-turnover funds are poor value – see Article 5.1. Some investment managers spread trading costs across all investors. However, many recognise that many of the transactions are forced on the fund because investors are coming into or leaving it. Where this happens, the transaction costs may be charged to those investors. Another cost might be performance fees if the manager does well relative to the market segment (around 5 per cent have performance fees). It may seem odd when your fund is down 10 per cent that a performance fee is paid, but this can happen if the market index is down 15 per cent in the same period.

- Exit charges: Some funds make an exit charge instead of an initial charge if you cash in within, say, the first five years.

Article 5.1 - How a 1% hidden fee wipes £100,000 from a £100,000 investment

By Attracta Mooney

An engineer and an architect invest £100,000 each in different funds that have an identical ongoing charges figure. The funds enjoy identical returns for 30 years but when the investors withdraw their capital, the architect has £100,000 less.

What happened? This is the riddle that consumer champions and investors have been trying to solve for years. The answer is clearer because of new European rules. Under Mifid II, asset managers must disclose a figure for the total cost of investing.

This has highlighted the various, and often high, fees that investment houses charge on top of the ongoing charges figure (OCF), which most investors use to understand how much they pay their portfolio manager.

Analysis by FTfm and the research company Lang Cat found that investors are paying up to four times the OCF in popular funds, including those run by Vanguard, BlackRock and Janus Henderson.

Mike Barrett, director of Lang Cat, says that although the costs on top of the OCF might look small initially, perhaps 30 basis points of additional charges, or 30p for £100 invested, they add up.

For example, an investor who pays a fee of 1 per cent a year on an initial investment of £100,000, and enjoys returns of 6 per cent a year over three decades, will end up with a pot of £432,194, according to Lang Cat.

If, however, hidden costs add an additional 1 per cent a year in fees, that pot will be just £324,340.

“What you might see as ‘just a few basis points’ makes such a difference over the years. The numbers can be startling over time,” Mr Barrett says.

He says investors have been surprised that the true cost of investing is so much more than expected. “Investment professionals, such as financial advisers, always knew there was this known unknown, that the OCF was not the complete picture,” he says. “But I think it was a reasonable assumption for retail investors to make — that if an asset manager said a fund had an OCF of 22bp, that was it and that there wasn’t another 50bp on top of that.”

Under Mifid II, asset managers must provide estimations of transaction charges, which are the cost of buying and selling stocks, as well as other incidental fees. In many cases, transaction costs have been far higher than even experienced advisers expected.

For example, the Polar Capital Japan I hedged fund has an OCF of 1.35 per cent but transaction costs of 1.81 per cent, raising the cost of ownership by 134 per cent.

Iain Evans, global head of distribution at Polar Capital, says the company’s fund prices, income payments and performance figures have always been shown and paid net of all fees, including transaction costs. “While we understand what the regulator is trying to achieve in terms of cost transparency, the net return that we deliver to our investors should be the ultimate measure of our value add,” he says.

“It is, of course, a matter of personal investor preference on the degree one is focused on the costs of a product versus the net money outcome, but we remain resolutely focused on delivering differentiated investment products and superior risk adjusted returns to our investors and believe that we can and do deliver value for money.”

JPMorgan Asset Management’s £908m European Dynamic ex-UK fund has an OCF of 93bp and reported estimated transaction costs of 1.68 per cent, lifting the ownership cost 180 per cent.

The Janus Henderson UK Absolute Return fund has an OCF of 1.06 per cent, as well as transaction costs of 79bp. If platform fees and a performance fee are charged, the total cost jumps to an average of 3.82 per cent annually if purchased via Hargreaves Lansdown, the UK fund distributor.

FE Trustnet, the data provider, created a list of 100 popular UK funds. It found that these had an average OCF of 88bp, but this jumped to 1.11 per cent once transaction costs were included.

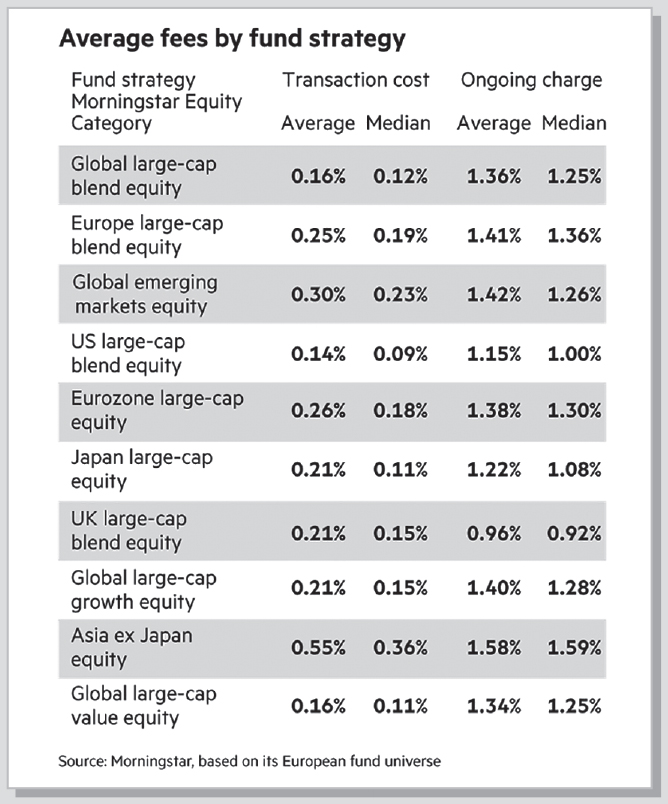

A look at additional costs across funds in Europe shows that transaction costs added 25bp to European large-cap funds and 55bp to Asia ex-Japan equity funds, according to Morningstar, the data provider.

Funds investing in US large-caps and global large-caps had the lowest transaction costs, according to Morningstar. Funds with high transaction costs are typically those that trade more. Investors will probably pay other fees, such as to their financial adviser or online broker.

Darius McDermott, managing director of Chelsea Financial Services, an online investor service, says the new rules reveal that hidden fees can reach “ridiculous figures”.

“There is some surprise at how much some of the charges are, especially with bigger funds where you would expect to benefit from economies of scale,” he says. Mr McDermott says: “Clearly there was a lack of transparency” from asset managers. He says that hidden costs are not the only aspect to which investors need to pay attention. He points out that an investor could put their money into a fund where costs are low but performance is bad. Another investor could be in a fund with high costs and high performance and be better off.

“The charges, in some instances, are bigger than we and the public expected. But if you get good performance after charges, that is an important argument,” he says.

“It would be damaging for people to look at fees only. The cheapest doesn’t mean it is the best.” Mr Barrett agrees that the high additional fees are not “necessarily bad”.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 10 February 2018.

© The Financial Times Limited 2018. All Rights Reserved.

How do you buy or sell units?

You can buy direct from the unit trust management company. Alternatively, you could buy through a financial adviser, broker or fund supermarket (platform). If you are worried by prices being set on a forward basis, you can tell your financial adviser or platform not to buy if the price goes above a limit.

When it comes to selling, you can sell units back to the management company (through an online broker account), which is obliged to purchase. However, some funds will only allow sales monthly, quarterly or twice yearly. This is because the money is invested in illiquid assets such as property – some of these assets will probably need to be sold to pay you back, which takes time. For funds, certainly for those invested in quoted shares and bonds, you should receive payment within five days, but if the fund has a lot of redemption requests in a short period it may take a while to sell securities and pay off unit sellers. You don’t have to sell all your holding – you can dispose of as much or as little as you want.

Returns

The return on a unit trust may consist of two elements. First, income is usually gained on the underlying investments in the form of interest or dividends. Second, the prices of the securities held could rise over time. Some units pay out all income, after deducting management charges and so on on set dates (usually twice a year)3 in cash. On the other hand, accumulation units reinvest the income on behalf of the unit holders, and as a result the price of accumulation units tends to rise more rapidly than income units. Financial websites show listings for prices of income (‘Inc’) units (also called distribution units) and accumulation (‘Acc’) units.

Accumulation units offer the benefit of avoiding reinvestment costs and the hassle to the unit holder of purchasing new units. As well as a trust issuing accumulation units and distribution units it may issue different units to institutional investors (with much lower management charges because they buy in bulk) than retail investors. Confusingly, these different classes are referred to as different share classes rather than unit classes.

Dividends paid by unit trusts and OEICs (see later) are treated in the same way as dividends from ordinary company shares in UK companies for tax. After the first £2,000 of dividend tax-free allowance is used up basic rate tax payers are charged 7.5%, but higher rate tax payers pay more (see Chapter 17).4 Interest distributions paid by UK unit trusts and OEICs paid gross are treated in exactly the same way as interest on bank, building society and local authority savings (see Chapter 17). However, higher rate tax payers have to declare the increase in accumulation units due to dividends and interest received, even though not sent to them, and pay extra tax (see Chapter 17). But these payments on annual income are deductible from any capital gains tax calculation after selling your units.

Types of trust available

There are over 200 fund management groups offering over 3,000 unit trusts or their cousins, the OEICs (see below) – www.trustnet.com allows you to search through a list. UK All Companies funds invest at least 80 per cent of their assets in UK shares (the Investment Association, www.theia.org, has 30 types of fund defined). To this classic type of unit trust have been added a very wide range of trusts with amazingly diverse objectives. Some funds focus investment in shares paying high dividends (UK Equity Income), others split the funds between equity and bonds (UK Equity and Bond Income), while some invest mostly in gilts or corporate bonds. Some place most of their money in smaller companies, some in Far East shares. A few trusts invest in property. The possibilities are endless. The main categories are:

- Income funds: They aim to produce a regular income from the underlying investments, which may be paid out to the investor or invested back into the fund.

- Growth funds: They aim to grow the capital over the long term, thus many investments may have low or no current dividends but have high capital gain potential. The funds that produce income as part of their total return usually reinvest it back into the fund.

- Specialist funds: This includes property funds and funds with a specialised and narrow investment focus, such as technology. The specialist absolute return funds rather than trying to beat a benchmark index, such as an index of European shares, aim to obtain a positive return even when particular share and/or bond markets are going down by switching to those sectors thought likely to rise. Thus, the manager has to be free to transfer money from one set of equity/bond markets to others quickly.

- Capital protection funds: These are funds that aim to protect your capital. There is some potential for investment return, but the main emphasis is on safety. Underlying assets might be short-term lending to highly reputable governments and companies.

Minimum investment

Some trusts ask for an initial minimum investment of only £250 or so, whereas others insist on at least £1,500. Thereafter you are often entitled, under a savings plan, to put in as little as £50. It is often possible to use shares instead of cash as payment for units through a share exchange scheme.

Key investor information document (KIID)

The KIID, produced by the fund, provides the most important facts in a standardised, jargon-free way, allowing comparison between funds and helping you to assess if a fund will meet your needs at a reasonable cost. It covers the following:

- Fund objective and investment policy (shares/bonds, geographical focus, business sector, say green energy firms only).

- Risk and reward profile. An estimate of the likelihood of the fund losing money on a scale of 1 to 7. Of course, risk and return are usually inversely related.

- Charges.

- Past performance over a number of years and degree of volatility.

- Other elements, such as how to obtain the prospectus, annual and half-yearly reports.

- Name of trustee.

Following your units’ progress

A manager’s report will be sent to you every six months detailing the performance of the fund over the half year or year and the events in the market(s) in which the fund invests, and explaining the manager’s investment strategy. It will also comment on future prospects, list the securities held by the fund and display the fund’s financial accounts.

At least once a year you will receive a statement showing the number of units you hold and latest prices. The statement will also give a run-down of any additional investment, reinvestment or encashments you have made since the last statement.

Between receiving reports and statements you can contact the management company over the telephone. They may be prepared to discuss the investment performance of the fund and current outlook. They will certainly be willing to deal with general administration queries and, of course, give information on other products they might sell you.

Many websites, such as fund supermarket websites (see later), carry details of units. You could visit the fund manager’s website, or go to a general site.

Useful websites

| www.citywire.co.uk | Citywire |

| www.markets.ft.com/data/funds/uk | Financial Times |

| http://www.fundlistings.com | Fund Listings |

| www.ii.co.uk | Interactive Investor |

| www.theia.org | The Investment Association |

| www.morningstar.co.uk | Morningstar UK |

| www.refinitiv.com | Refinitiv |

| www.standardandpoors.com | Standard & Poor’s funds |

| www.trustnet.com | Trustnet |

Switching funds

Many fund management companies allow you to switch from one trust within its stable to another for a charge much lower than the usual initial charge. So, if you think US hi-tech has reached its peak you might ask the manager to transfer your holding to a UK smaller company fund.

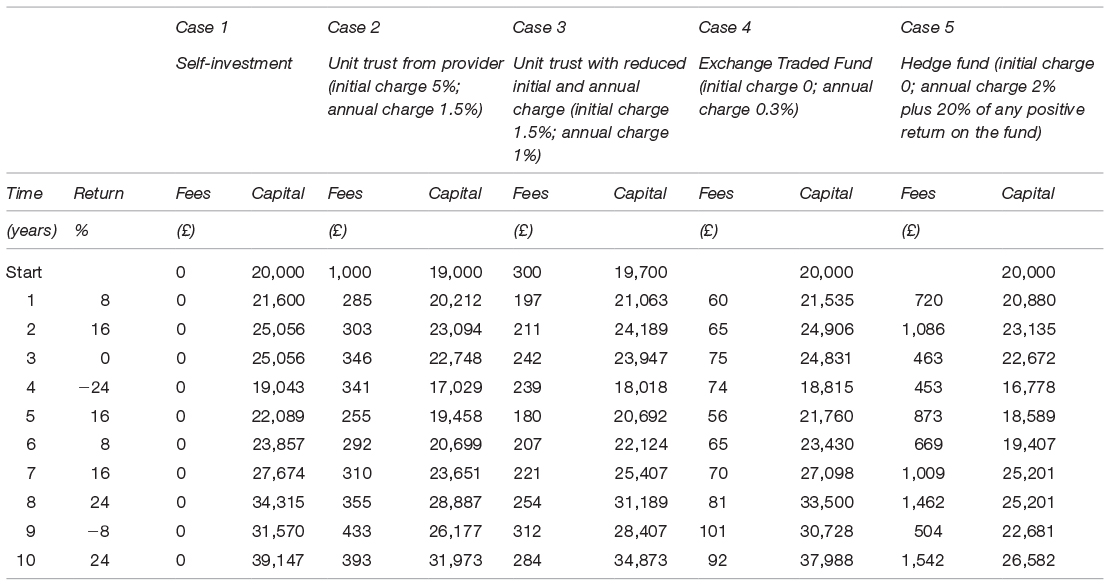

Active versus passive?

It costs more to run a fund in which the manager is spending time and effort carefully selecting shares (an ‘actively managed’ fund) than one where the manager simply buys and holds a broad range of shares matching a market index (e.g. FTSE 100), called a tracker (or passive or indexed) fund. Study after study concludes actively managed funds fail to outperform the market (on average). Some active managers will outperform, but how much of that is due to random chance and how much is due to superior ability is very much moot. After all, put 100 idiots at a roulette wheel and some will walk home wealthy – evidence of fat wallets (or their backers’ wallets) does not make them smart. The fund management industry is not populated by idiots. There are some very smart fund managers, using sound investment principles. And, over many years it is possible to observe some extraordinary returns. However, it is difficult to identify real investing skill before the event and many out-performers over three or four year spans are simply lucky.

Trackers will also underperform the benchmark index, but at least the ongoing costs of the fund are significantly less than most actively managed funds. Typically, trackers’ ongoing costs are between 0.2 per cent and 0.3 per cent, while actively managed funds are around 1.5–1.8 per cent if you include the adviser’s or platform’s charge for holding your investments. You need to be convinced of superior security picking skills of your chosen manager to sacrifice 1.8 per cent of your annual return. This small sounding sum could amount to 25 per cent or more of your fund over a decade or so.

If you invested £20,000 in a fund with no charges, and it grew by 6 per cent annually for 20 years, you would get £64,143 – just over £44,000 growth. If you invested in an active fund with the industry typical ongoing charge of 1.67 per cent, your fund would be reduced to £46,689, meaning £17,454 of your growth goes on charges. If the ongoing charge is 2.5 per cent, about £24,000 would be lost due to charges. That is not even factoring in other costs, such as transaction costs of security dealing.

John Authers, a commentator on investment matters at the Financial Times, leaves us in no doubt concerning his view that active funds are generally too costly for the service they provide – see Article 5.2. Bear in mind that the high charges are often levied to cover the fiddly business of dealing with investors putting in only a few thousand pounds. Larger investors, such as pension funds buying unit trusts, benefit from much lower charges. Charges for investors in US funds have fallen under the pressure of investors’ insistence, in the light of the evidence of low costs being vital to overall returns, to an average of 0.55 per cent for equity funds, about half that of 20 years ago.

American investors seek out cheap funds more than Europeans. Consider this though: there is a major problem with too much passive investing. Without a large body of investors and managers actively looking for underpriced securities the market would drift to inefficient prices, so there is a limit to the proportion of shareholdings that should be held passively without thought to the value of the underlying shares.

Article 5.2 - Beware the costs of actively managed funds

By John Authers

Why defend the indefensible? Traditional actively managed mutual funds [e.g. unit trusts] are obsolete. They have nothing left to recommend them. And yet attempts to point out the blatant superiority of newer passive investment products provoke furious defences from brokers.

Their arguments are so threadbare that they can only be motivated by a desire to keep the commissions coming. But they are a formidable obstacle to needed change.

Let us be clear about the model that must be replaced; managers try to beat market indices with a portfolio of about 100 stocks. Such diversification makes it hard to beat the market. But the risk of being caught in a crash is undimmed. And while many managers are smart enough to beat the market, they cannot do so and still pay themselves decently.

A recent survey by the London investment consultancy Style Research of how 425 global equity funds benchmarked against the MSCI World index performed last year makes this clear. Measuring the performance of the funds’ holdings, without including costs, 59 per cent of them beat the index. Once costs to investors were included, only 31 per cent beat the index. So 28 per cent of the funds had index-beating managers who charged too much in fees to allow their clients to beat the index.

Looking at European equity mutual funds, Karl-Heinz Thielmann of Long-Term Investing Research in Karlsruhe found their total average costs (including bid-offer spread, market impact [buy/sell orders move share prices on the market adversely for the trader], and costs caused by managing in- and outflows of money from clients) were about 4 percentage points (3 percentage points in the US). Their outperformance, before costs, was about 2 percentage points.

How, then, to reduce costs? The best answer yet devised is to offer index funds, which merely replicate the index. This can be done cheaply with computers. But index funds tend not to pay much commission. This spurs brokers’ ire.

First, they argue that active managers can take evasive action in a market dive, while index funds blindly fall with the market. This is specious on several levels. Active managers underperform consistently, throughout bull and bear markets. Over the past five years, according to Morningstar, 61 per cent of balanced funds and 67 per cent of US equity funds failed to match their index.

Moreover, they are paid to pick stocks, not to time the market. It is not an equity fund manager’s job to make a big switch into bonds or cash. And the argument for index funds is not that they are lower risk, but that due to their lower costs their returns for any level of risk are likely to be higher than for equivalent active funds.

A second argument is that index funds are guaranteed to lose to the index, thanks to their costs. This is true, but specious. The odds are that they will perform better than an active fund. And they enjoy economies of scale. For example, the SPDR, which tracks the S&P 500, had a 2012 return just 0.01 percentage point less than that of the S&P, according to Bloomberg.

A third argument is that choosing index funds entails ignoring active managers who consistently outperform. But this small band of managers may be exactly the ones to avoid. History shows that persistent outperformance attracts inflows, which increases costs for the fund, and makes it harder to outperform. Eventually performance comes crashing back to earth.

Indexing’s critics have one decent argument. Index funds are dumb. They buy at whatever valuation the market offers. If everyone invested through index funds, markets would cease to function; nobody would be seeking out inefficiencies.

How to deal with this? One way is to find low-cost ways to manage funds without accepting market valuations. For example, funds can buy only stocks that appear cheap by a specific metric. Another option is to abandon diversification and really try to beat the market. This is risky. But according to Morningstar, most sector fund managers, investing only in a small universe of stocks, do beat their benchmarks. When combined with index funds inside pension funds, such funds make great sense.

The industry has far to go before future retirees get the deal they deserve. But its current modus operandi burdens investors with too many costs. This must change. When brokers brandish the rosy five-year returns of active mutual funds, they will be defending the indefensible.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 5 April 2013.

© The Financial Times Limited 2013. All Rights Reserved.

Article 5.3 discusses the poor performances of European fund managers.

Article 5.3 - Few funds sold to retail investors beat benchmark after fees

By Chris Flood

Less than one in five of the funds sold to retail investors in Europe in the past three years outperformed their benchmark after fees were taken into account, says research by Prometeia.

The Italian consultancy examined the three-year record of 2,500 equity, bond and money market funds, with combined assets of €1.8tn, and found that only 18 per cent beat their benchmark.

Claudio Bocci, head of the asset management advisory team at Prometeia, said: “Many managers are unable to compensate for fees because they are not taking enough active risk, so they are very unlikely to beat their benchmark. This is a structural problem”.

Performance records suggest that many fund managers struggle to deliver consistent success. Half the top-ranked managers of global and European equities, global bond and flexible balanced funds, measured by returns over three years, drop out of the top performance decile over the following 12 months.

Huge gaps also exist between the best and worst managers across all fund types, complicating the decisions facing retail investors.

Mr Bocci said there was widespread misalignment between the fee structures and expected returns of many funds sold to retail investors in Europe.

Prometeia estimated that up to a quarter of the funds (mainly bond and money market products) sold to retail investors faced a near-impossible challenge in delivering above-benchmark returns net of fees.

“Some of these conservative funds have close to a 100 per cent probability that they will fail to beat their benchmark because of costs. This is not a sustainable position,” said Mr Bocci.

Prometeia’s findings echo criticism by the European Commission, which last month highlighted large variations in the cost of investment products and the quality of advice provided to retail investors across Europe. “Today, an average consumer is overwhelmed by the sheer complexity and uncertainty associated with investment products. Most households do not invest at all in capital markets or do so very infrequently across their lifetime” said the commission.

Mr Bocci said he expected further rationalisation of fund selectors’ catalogues as Mifid II would encourage them to use more high-quality products. He added that just a fifth of the 3,700 fund share classes sold to retail investors in Europe could be judged as high quality, according to Prometeia’s assessment based on returns, risks, and performance persistence measured over different timespans.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 13 May 2018

© The Financial Times Limited 2018. All Rights Reserved.

While many active managers pretend to be actively sifting companies to select only the most underpriced, in reality they create portfolios that are very similar to a broad cross section of the market – ‘index huggers’ or ‘closet trackers’ or ‘closet indexers’. And yet they charge the high fees of proper active managers.

Article 5.4 - Pull closet indexing out of the closet

By John Authers

In the UK, people are trying to pull closet indexing out of the closet. It is a fight that could have global implications.

This is one issue on which there is no need to sit on the fence. The debate between active managers, who try to beat their benchmark, and passive managers, who merely track it, will go on and on. But everyone can agree that there is no case for closet indexing – the practice of running an “active” fund, charging active management fees but, in practice, offering an investment that merely hugs the index.

This is, in effect, a tax on millions of investors, for no economic benefit and helps pump up asset bubbles. It impedes capitalism and the efficient allocation of capital.

A report published last month by SCM Private, a London-based investment adviser, described closet indexation as “a UK epidemic”. After analysing £120bn in UK funds, it alleged that investors could have saved £1.86bn in fees if they had switched from underperforming UK equity funds to alternative cheaper index funds.

SCM Private emotively accused the UK fund industry of “systematic abuse of the public” and alleged that it had failed to behave with integrity. This is strong language, so let us look at the charges in detail.

Closet indexing has been well explored in academia. It is measured by “active share”, a concept invented by the Yale academics Antti Petajisto and Martijn Cremers. For US funds benchmarked to the S&P 500, it measures the fraction of a fund’s holdings that differ from the S&P. For example, if a fund’s holdings are identical to the index, except that it holds no shares in Apple (worth 5 per cent of the index) and has invested that money elsewhere, it will have an active share of 5 per cent.

A passive index tracker has no active share. A fund that invests only in obscure stocks not in the benchmark has an active share of 100 per cent. Once active share drops below 60 per cent, the academics said, a fund is a possible “closet indexer”.

SCM Private found that only 24 per cent of 127 UK funds benchmarked to the FTSE-All Share index had an active share above 70 per cent. This compares with 65 per cent of a sample of US funds that had an active share this high.

Overall, the UK funds had an active share of 60 per cent, compared with 75 per cent in the US.

The chances are tiny that a few tweaks to the index would do well enough to overcome the extra fees that active managers charge, which are on average three times the fees charged by trackers. And indeed 88 per cent of funds with an active share under 50 per cent did not match their index.

Why does this happen? The problem derives from the incentives for fund managers who are paid not to beat the market but to accumulate assets. This is because they charge a percentage fee on assets under management and are judged by comparison to their benchmark index and to their peers. To hold on to assets, therefore, it is vital not to underperform their peers. Make a big contrarian bet and you may be separated from the herd. So everyone herds into the same stocks.

As passive investing through index trackers has taken hold, active managers have grown more conscious of their benchmark index. This is clear from the language they use. Two decades ago, a portfolio manager would say he “owned” a stock. Now he is more likely to say he is “overweight” it, always implicitly comparing with the index.

This phenomenon helps create investment bubbles, as overvaluations naturally occur when everyone invests in the same thing.

It also creates opportunities for those who have the courage to search for them. SCM Private found that 72 per cent of the UK funds with a high active share succeeded in beating their index. This is in line with international research. The Cremers and Petajisto research found that in the US, funds with the highest active share beat the index by more than 1 per cent per year, even after taking their fees into account.

The UK is not alone. Research led by Mr Cremers looked at 21,684 funds in 30 countries, managing some $10tn as of December 2007. Closet indexing was dominant in some countries, accounting for 40 per cent of equity funds in Canada, and 81 per cent in Poland.

It also found that countries with the most explicit indexing were also likely to have less closet indexing, while active funds there would charge lower fees. Passive trackers provided stiff discipline for the rest of the sector. It also found that most active funds fail to beat their benchmark – but that the more genuinely “active” a fund, the more likely it was to outperform.

Fixing the problem needs a radical overhaul of the way fund managers are paid. For now, funds must be forced to publish their active share. Before being flushed down the toilet, closet indexing must be pulled out of the closet.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 4 October 2013.

© The Financial Times Limited 2013. All Rights Reserved.

Points to bear in mind when choosing a unit trust

Unit trusts should be viewed as medium- to long-term investments, given that the up-front charges are so high. It is no good flitting in and out.

Advertisements showing a fund manager’s performance should be taken with a large pinch of salt. They will be very selective about the starting date (choosing a low point) in order to impress you. Furthermore, there is a mass of evidence to show that past performance is a very poor guide to how well a fund will perform in the future. It is very unusual for a fund to outperform consistently over the medium and longer term. Surprisingly, often top performing funds over one- or five-year periods end up falling to the bottom of the league tables in the next period. Novice investors are often lured into buying recent top performers, only to find that the sector where the fund focuses turns out to be in a bubble, and future returns are disappointing. Even if you find a fund that has shown a sustained high performance you may then discover that what made the fund work well in one economic period serves less well in the next. Also, outperformance may be due to taking more risk.

A dilemma arises for investors when a fund manager leaves a management company. Should you stick with the trust or move with the manager? This is a serious issue given that less than two-thirds of managers have run their funds for as long as three years. Following a ‘star’ fund manager to a new company is not always possible, and besides the costs of doing so can be high. Some funds have one star player, while others have a talented team. Going for a team may leave you less vulnerable to the departure of particular managers. Citywire (www.citywire.co.uk) tracks the performances of individual fund managers rather than funds.

It is possible for your money to be trapped within a unit trust. In 2008, when property prices were plunging and it became difficult to sell property, a number of property unit trusts announced that unit holders could not redeem units without giving months of notice for fear that the managers would become forced sellers of assets at distressed prices. In 2019 Neil Woodford blocked redemptions (a redemption gate) from his Equity Income Fund after serial underperformance led to an investor exodus. He did it to give more time sell unlisted and illiquid shares at better than fire-sale prices.

Article 5.5 - Conflicts of interest in fund manager market exposed by Woodford

Celebrated investor’s decision to run an open-ended fund suited everyone except investors

By Jonathan Ford

In the days since Neil Woodford shuttered his Equity Income Fund to redemptions, many have questioned why the celebrated asset manager ever structured this one-time £10bn monster as an open-ended investment scheme.

The main perceived benefit of such funds is the ATM-like promise of instant liquidity. Which means the manager must always be prepared to liquidate to satisfy redeeming investors. Yet Mr Woodford’s prized forte was long-term investing, not benchmark-hugging. Not only had he put the fund into some illiquid unquoted investments, thinking they would do better in the long term, Mr Woodford had even gone so far as to stop paying his staff short-term incentives. He preferred to put them on straight salaries to keep them focused on the longer goal.

Mixing long-term strategies with ATM promises created a vulnerability that might have been avoided had he established a closed-end fund that was not at risk of opportunistic liquidation. Indeed, the open-ended structure contributed to the pickle that Mr Woodford and his investors now find themselves in.

So why do it? Those seeking an answer could do worse than follow the investor’s dollar. Independent financial advisers such as Hargreaves Lansdown and St James’s Place are the key gatekeepers for retail investors. For the IFAs, there’s a financial advantage to peddling open-ended structures. While these may not be as lucrative, fee-wise, as more specialist asset classes such as private equity, they are marketable to the widest retail audience.

And that’s not their only merit. Open-ended funds are also easily scalable, subject only to demand or the fund manager’s discretion. In this they differ from closed-end schemes, such as investment trusts, which take a fixed chunk of money. IFAs can put such products on their platform’s so-called “best buy” lists for steady sale, negotiating a discount with the manager and inserting their own fees gently into the compensation equation.

Marketing Mr Woodford’s fund was lucrative for Hargreaves Lansdown. When the manager obligingly cut his fees they were able to shoehorn in their own charge of 0.45 per cent per annum on top. The firm carried on flogging the fund long after its decline. As to Mr Woodford himself, well the answer perhaps lies in the symbiotic relationship between the manager and these marketing machines. As a star manager setting up on his own, he had a strong incentive to play by the rules set by the biggest retail gatekeepers.

Whatever the fund management industry claims, the overwhelming desire remains to gather assets, assets and more assets. That’s because success at the top for a manager may be fleeting. While you are still in vogue, there is a visceral wish to cash up when you can. Surveying this patchwork of poor incentives, it is hard to escape the irony. By piling on too many funds too quickly, Mr Woodford actually set himself up to fail. He bid up his chosen pool of stocks with the wall of cash he had assembled. That made their subsequent underperformance more certain. As for the unlisted stocks he bought, they seem to have been a way of diversifying away from overpriced holdings — albeit one that badly misfired. The one party uncatered for in all this, of course, is the end investor. While the intermediaries are all acting rationally in their own interests, its outcome — and that of society — is distinctly third rate.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 9 June 2019

© The Financial Times Limited 2019. All Rights Reserved.

Some funds can grow too big. For example, a fund focused on small French companies that has €1 billion under management may not be able to limit itself to the true bargains, or even to small companies, given that the manager has to invest somewhere.

Some funds can be too small. Many of the costs of running a fund are fixed, such as the manager’s research time, thus average costs per unit can rise if there is only a few million to invest. The fund management house may bear the extra costs for a time, but if there is no improvement, eventually it will close.

Few fund managers invest a substantial proportion of their own wealth in their funds.

Article 5.6 - Impetus for managers to invest in own funds

By Ruth Sullivan

Fund managers who put their own money into the funds they run are less likely to take undue risks and expose investors to big losses. That is the theory anyway, and there is growing interest in the practice.

“Having skin in the game is gaining traction but is more prevalent in the US and the UK than in continental Europe,” says Amin Rajan, chief executive of Create Research, a consultancy. However, the increase has been slow.

According to a survey of global managers by Citi and Create Research, just 8 per cent put their bonuses into the funds they manage, while a further 13 per cent plan to in the next 12 months. Some asset managers require their fund managers to defer as much as half of their bonus by investing it into their own funds over a three to four-year period, which can be “a big incentive for managers”, says Pars Purewal, at PwC. This requirement is increasing in the UK because of the need to align interests between fund managers and clients and “prevent managers taking unnecessary risks”, he adds.

Much depends on the culture of the asset manager. Some believe it is an essential part of the business ethos, making investors feel more confident. Henderson Global Investors, a UK-based investment house, is one of these. “Most fund managers invest a meaningful amount in their funds [here]. It shows their interests are aligned with investors,” says Jamie Legg, at Henderson.

“It is a genuine conviction in the stocks they run. Why wouldn’t they?” says Mr Legg.

Vanguard Group, a US asset manager, takes it a step further and has “a client pledge to invest our own money alongside our investors”, says Tom Rampulla of Vanguard Investments UK.

However, not all investment houses believe it is necessary for long-only managers to invest in their own funds. Most funds are designed to track and beat indices and most of the returns will be driven by what the benchmark does.

In the US, where disclosure of how much managers invest in their own funds has been obligatory since 2006, there is evidence of a growing trend to co-invest.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 9 January 2011.

© The Financial Times Limited 2011. All Rights Reserved.

A couple of technical terms

Undertaking for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (UCITS) are open-ended funds regulated under European law that can be marketed freely across EU member states.

Non-UCITS Retail Schemes (NURS) are funds authorised to be sold to the public in the UK that are not governed by the European regulation of funds under the ‘UCITS Directive’, because they invest in assets, such as gold funds, that the Directive does not permit or comply with different concentration limits. They are required instead to meet standards set by the UK financial services regulator.

Open-ended investment companies

Open-ended investment companies (OEICs, pronounced ‘oiks’) have been around since the late 1990s, and many unit trusts have turned themselves into OEICs. OEICs are very similar to unit trusts, so most of what has already been said applies to them. A crucial difference is that an OEIC is a company that issues shares rather than a trust that issues units. One similarity is that it is ‘open-ended’ in that it can expand or contract the number of shares in issue in response to demand. Also OEICs are regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in a similar way to unit trusts, so investor protection is much the same. Investment in OEICs may also be made on a regular basis, say £50 per month, or as a lump sum.

An OEIC has an authorised corporate director (ACD) managing the fund. It also has a depositary (usually a large bank) which, similar to the trustee for a unit trust, ensures safekeeping of the assets (custody), collecting of income, the delivery and receipt of underlying securities and the payment of tax. The oversight of the duty of care element is undertaken by the OEIC board of directors. The ACD’s remit is to invest shareholder’s funds in accordance with the OEIC’s objectives under the oversight of the board of directors. Compared with unit trusts, OEICs have a simpler pricing system because there is one price for both buyers and sellers. Charges and dealing commissions are shown separately (which makes them more transparent than unit trusts). When OEICs are bought or sold the price is directly related to the value of the underlying assets and not based on the supply and demand for its shares (as with investment trusts – see later). The price is calculated daily, usually 12 noon in London. Some OEICs charge an exit fee.

The OEIC (and unit trust) may be a stand-alone fund or created under an ‘umbrella’ structure, which means that there are a number of sub-funds each with a different investment objective (one sub-fund may focus on US shares, another on UK shares, etc). Each sub-fund could have different investors and asset pools. The advantage to the investor of the umbrella structure is that reallocating money within one fund management group to different investment categories is made easier and cheaper.

When there are a large number of new purchasers (or sellers) of OEIC shares the fund may incur high costs to buy (sell) underlying securities, such as broker fees and share bid-offer spreads. This damages the interests of older holders of OEIC shares. To balance the interests of the old and new holders the new members may be charged a dilution or adjustment levy (typically 0.5–2 per cent), the proceeds of which are held in the fund rather than being extracted by the manager. An alternative is to apply a swinging single price which adjusts the buy/sell price to include the transaction costs for the shareholder doing the transaction.

Exchange traded funds

Exchange traded funds (ETFs) take the idea of tracking a stock market index or sector a stage further. ETFs are set up as companies issuing shares. The money raised is used to buy a range of securities such as a collection of shares in a particular stock market index or sector, such as the FTSE 100 or pharmaceutical shares. They are open-ended funds – the ETF shares are created and cancelled as demand rises or falls. However, they differ from unit trusts and OEICs in that the pricing of ETF shares is left up to the market place. ETFs are quoted companies and you can buy and sell their shares at prices subject to change throughout the day (unlike unit trusts and OEICs, where prices are set by formula once a day).

Despite an ETF’s price being set by trading in the stock market they tend to trade at, or near to, the underlying net asset value (NAV) – the value of the shares in the FTSE 100, for instance. This is different from investment trusts, which frequently trade significantly below or above net asset value.

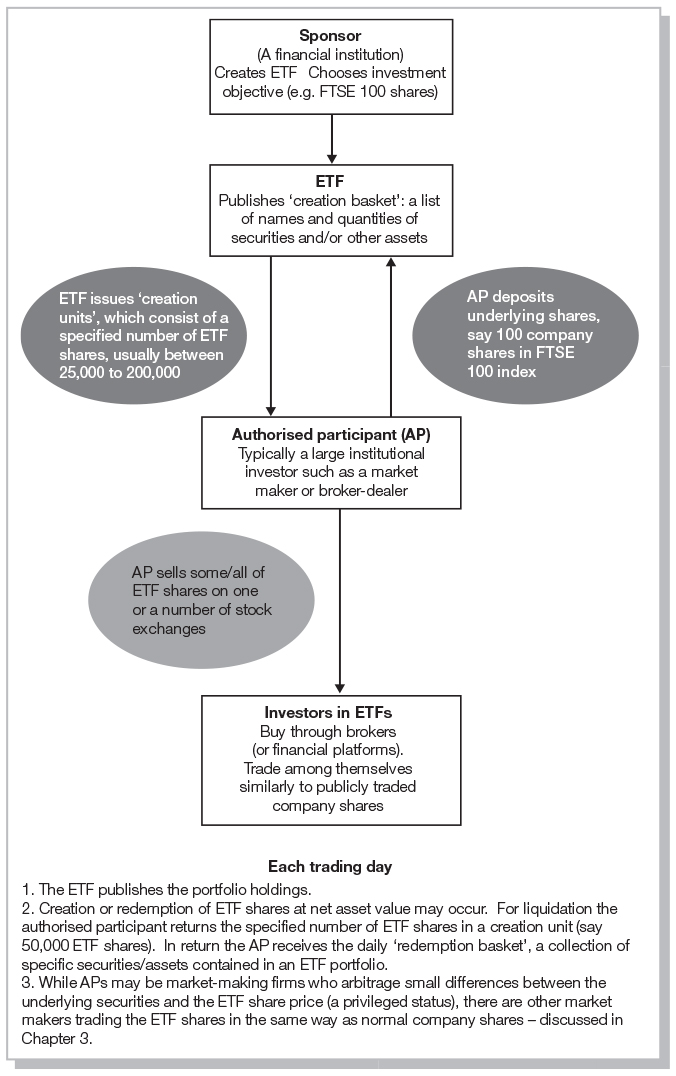

Newly created ETF shares are delivered to market makers (or other ‘authorised participants’) in exchange for an entire portfolio of shares matching the index (not for cash). The underlying shares are held by the ETF fund manager (ETF sponsor), while the new ETF shares are traded by the market maker in the secondary market. To redeem ETF shares, the ETF manager delivers underlying shares/securities to the market maker in exchange for ETF shares. ETF managers only create new ETF shares for market makers with at least £1 million to invest, so private investors are excluded at this level. However, private investors can trade in existing ETF shares in the secondary market.

If the price of an ETF share rises above the value of the underlying shares, there will be an arbitrage opportunity for the market maker. Arbitrage means the possibility of simultaneously buying and selling the same or similar securities in two markets and making a risk-free gain –buying bananas for £1 in one market and selling them for £1.05 in another. In this case the ETF share representing, say, the top 100 UK shares is trading above the price of the 100 shares when sold separately. Market makers, spotting this opportunity, will swap the underlying basket of shares for a creation unit of ETF shares, thus realising a profit by then selling the ETF shares into the market. Then the new supply of ETF shares will satisfy the excess demand and ETF prices should fall until they are in line with the underlying NAV.

If the ETF share price falls below the underlying shares’ value, the market maker will exploit this by having the ETF shares redeemed by the ETF manager. The market maker ends up with the more valuable underlying shares and the supply of ETFs in the market place has fallen, bringing the price back up to the NAV.5

While the essence of the process creating ETFs and the relationships between market makers and ETF managers is as described above, it is a little more complicated than this. If you would like to know the technicalities read more about them below.

An advantage arising from market makers and ETF managers not handing over cash, but instead swapping ETF shares and underlying shares, is that there are no brokerage costs for buying and selling shares. This makes transactions cheap.

Spreads for investors – the difference between the buying and selling prices of ETFs on stock markets – are generally around 0.1–0.3 per cent (although spreads can widen to 10 per cent or more at times of extreme volatility, for example, after 11 September 2001). While there is no initial charge with ETFs, annual management charges plus other costs (the total expense ratio) range between 0.09 and 0.75 per cent but are typically between 0.3 and 0.5 per cent – these are deducted from dividends.

ETFs are sometimes a more expensive way of tracking an index than some particularly cheap unit trust and OEIC passive funds because they incur additional costs in ensuring trading ability through the day and in paying a stock market listing fee. But overall the low-charging providers of ETFs, unit trusts, OEICs and investment trusts have comparable fees, but note the need to look for the low charging ones. A typical ETF, if there is such a thing, has a lower ongoing charge than a comparable unit trust or OEIC. In addition to the ongoing charge there may be fees to make use of an index (the FTSE might charge, for example), to service an account and to pay custodians to look after the assets.

Private investors purchasing ETFs from brokers will be charged a minimum of £10 to £40 per trade. No stamp duty is payable on purchase, nor does the ETF pay stamp duty when it purchases underlying shares, etc. Prices and other information are available at many free websites, such as www.londonstockexchange.com.

There are thousands of equity ETFs, from those that track the US market (S&P 500 index) or European shares (EURO STOXX 50), to more specialised funds such as information technology companies across the globe. There are also hundreds of ETFs with bonds as the underlying securities. In all, over £4,000 billion is invested in ETFs worldwide.

ETFs pay dividends in line with the underlying constituent shares or other income such as interest on bonds, quarterly, semi-annually or annually. This is reflected in the ‘yield’ quoted on financial websites such as iShares (www.ishares.com), Deutsche (etf.dws.com) and Trustnet (www2.trustnet.com/exchange-traded-funds). Make sure the yield you see quoted is the sum of the historic 12-month distribution payments made by the ETF divided by the ETF price after deduction of account charges, to compare across providers. Some yields are what the underlying holdings pay out rather than what the ETF pays. Morningstar (www.morningstar.co.uk/uk/etfs) corrects for this when comparing ETFs.

Recent innovations

We have moved a long way from the simple traditional equity ETFs developed in the 1990s and described above. Nowadays the ETF may not purchase all the shares in the index but merely a sample. This is useful for ETFs invested in, say, Chinese or Vietnamese shares where government restrictions may prevent purchasing all the shares in the index. Also, the exchange-traded concept has been extended beyond equities and bonds to foreign exchange rates, property, commodities and commodity indices (exchange traded commodities, ETCs).6

Instead of the provider holding the underlying instrument or commodity the investment is in swaps or other derivative instruments (holding a ton of actual pork belly for lengthy periods may be a wasting asset). Derivatives are also used for hundreds of equity and bond ETFs.7

The problem with derivative-based ETFs is that there is a risk that the counterparties providing the derivatives may not be able to meet their obligations and then the ETF holder may not have anything tangible backing up the ETF shares. Also if the ETF does not buy the underlying securities but instead relies on derivatives, and then goes bust, it could be more complicated for the investor to retrieve their investment. That said, many markets cannot be accessed through the traditional route and derivative value movement is the only option to track a market. Also swap-based deals can be cheaper than buying shares in 100 companies.

The use of derivatives for many EFTs – ‘synthetic replication’ of an index – has stimulated debate in the ETF world as to whether ETFs consisting solely of derivatives are truly ETFs at all. But, regardless of some misgivings it looked as though the volume of synthetic ETFs would overtake that of the traditional physical ETFs (‘physical-replication’). Then the financial crisis of 2008 happened, when synthetic ETFs looked shaky as financial institutions guaranteeing swaps and other derivatives came close to going bust themselves. Synthetic demand peaked and has fallen since 2012 while the demand for fully backed physical ETFs trebled. Today over three-quarters of ETF assets are held in physicals. Precious metal ETCs must be backed by the physical asset, but softer commodity ETFs are usually synthetic. The Americans never took to synthetic ETFs.

Another ‘innovation’ in the field is the creation of actively managed ETFs. This really does confuse the picture. Instead of passively tracking an index the managers of these instruments try to outperform it by picking winners. Of course, they need compensation for the intellectual effort, which means that fees are higher, negating the most important selling point of ETFs.

A further move is for ETFs to ‘short’ the market, so that they rise in value when the market falls (through derivatives). Going even further, you can get double the effect of the market fall. Not only are these types of ETFs more expensive to hold, but the other side of the coin from gaining double if you guess right is that you lose double if you guess wrong. As well as these ‘inverse ETFs’ there are other ‘leveraged’ ETFs that rise a multiple of an underlying market’s rise.

Advantages and disadvantages

Among the advantages of ETFs are the following:

- They are listed companies on stock exchanges with active secondary markets. Being open-ended, there is no danger of over-supply of shares as ETF managers always stand ready to buy.

- They trade at, or very near to, net asset value and track the index closely (although some are closer than others) – a smaller ‘tracking difference’.

- They can be traded at real-time prices throughout the day.

- They incur low management and other costs, which are transparent.

- No stamp duty is payable.

- Many can be held in an ISA or self-invested personal pension to save tax. Non-UK registered ETFs may not have these tax benefits – check before buying.

- They can be bought to gain exposure to foreign markets cheaply.

- ETFs offer a much wider choice of markets to track than unit trusts trackers, ranging from Brazilian shares to commercial property and hedge funds.

- There is transparency on what your money is invested in with physical ETFs.

There are, however, disadvantages:

- Stockbrokers’ fees can eat into profits of frequent traders.

- If the ETF provider does not buy the underlying securities, but instead relies on derivatives, additional risks are introduced.

- If you want to drip-feed money into your fund each month this is likely to be more expensive with an ETF than a unit trust or OEIC because of the charges associated with buying and selling.

- Physical ETFs may lend out the shares in the portfolio to other financial institutions for a fee (who may, for example, sell them expecting to buy them back later at a profit). If they do not return them, investors in the ETF are exposed to the risk of loss (despite the holding of some collateral from the borrowers). The risk of such a failure is very small, but not unimaginable. Check to see if your ETF provider lends its securities, and whether the fees received are split with you.

- There is no Financial Services Compensation Scheme protection (see Chapter 19) if the fund goes bust.

- ETFs have become so big that their buying and selling actions move markets. Consider a £2 billion ETF invested in junk bonds (see Chapter 6), but a general loss of confidence in the economy will lead to an avalanche of sell orders for the ETF. The EFT sponsor would be obliged to redeem them by selling the underlying junk bonds just at a time of market panic when there are few buyers around.

Article 5.7 - How would ETFs fare in a market downturn?

Exchange traded funds may be cheap, but they come with a host of risks and are largely untested

By Ian Smith

This fast-growing investment vehicle is rewiring investors’ interaction with the public markets, but as it has grown so have concerns about whether it is distorting market valuations and feeding volatility.

With all the money that has rushed into ETFs over the past decade, no one quite knows what will happen when the current bull market for equities, in particular, comes to an end. Are retail investors aware of the risks to which they are exposed? How would the complicated infrastructure underlying these investments function at a time of market stress?

Most ETFs in Europe are so-called “Ucits” products, so fall under the same regulatory rules as their fund cousins, providing some security in the segregation of underlying assets. The end of the current bull market will partly play out through ETFs, and there is uncertainty about how they will withstand sudden shocks.

How it could come undone

If the robustness of ETFs as an investment vehicle has yet to be tested by a sustained market sell-off, there have been other signs to unsettle investors. ETFs played a role in the flash crashes of May 2010 and August 2015, as the market-making activity that underlies even the most straightforward fund broke down.

The US Securities and Exchange Commission’s review into the 2015 episode makes sober reading. According to the SEC, exchange traded products (including ETFs and more) “experienced more substantial increases in volume and more severe volatility” than standard stocks.

The market making activity behind ETFs is intended to make sure that the fund rarely trades at a discount or premium to its net asset value: in other words, it mirrors the value of the stocks or bonds held within it.

But this relies on the market makers, so-called “authorised participants” — commonly an investment bank — buying when units are at a discount to the underlying assets, and selling at a premium.

The suspicion is that those players are happy making a margin by providing liquidity in calm markets, but that they will disappear if things get choppy.

There are nonetheless reasons to be optimistic. In the largest products, where most of the money sits, about 90 per cent of trading that occurs is in the secondary market, according to Vanguard’s research. That means ETF investors are passing investments between themselves, and not having to transact with fund managers.

Those defending ETFs argue that there is a range of investors with different time horizons, including longer-term investors who will hold through the cycle. If buyers could not be found in the secondary market, the market makers will turn to the fund managers, or “sponsors”, to source the units.

In the worst-case scenario — the manager struggles to sell the underlying securities — the ETF investor could be handed them in lieu of cash. So when buying an ETF, an investor should consider whether they are happy, in an extreme case, to end up holding those underlying investments. Would you be happy to dispose of some high-yield bonds?

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 13 October 2017

© The Financial Times Limited 2017. All Rights Reserved.

Investment trusts (investment companies)

Investment trusts (companies) place the money they raise in assets such as shares, gilts, corporate bonds and property. Unlike unit trusts, they are set up as companies (they are not trusts at all) and are subject to company law.8 If you wish to place your money with an investment trust you do so by buying its shares. Investment trusts are floated on the London Stock Exchange where there is an active secondary market. They are described as closed-end funds because they do not create or redeem their shares on a daily basis in response to increases or decreases in demand (in contrast to unit trusts, OEICs and ETFs). The number of shares is fixed for a long period of time, as with any other company that issues shares.

The trust will have a constitution9 that specifies that its purpose is to invest in specific types of assets. It cannot deviate from this. So it may have been set up to invest in Japanese large company shares, US biotechnology shares, or whatever, and it is forbidden from switching to a different category of investment. This reassures the investor that money placed with a particular trust to invest in, say, UK large companies won’t end up in Russian oil shares. Of course, if you want to take the risk (and possible reward) of investing in Russian oil shares you can probably find an investment trust that specialises in these. There are, after all, about 380 investment trusts quoted in London, with total assets of over £160 billion, to choose from.

As a company an investment trust will have a board of directors answerable to shareholders for the trust’s actions and performance. With investment trusts being closed-end funds the amount of money under the directors’ control is fixed, which enables them to plan ahead with confidence unconcerned that tomorrow investors may want to withdraw money from the fund. Investors cannot oblige the trust to buy the shares should they want to sell (in contrast to unit trusts and OEICs). They have to sell to another investor at a price determined by the forces of supply and demand in the secondary market. Purchases and sales are made through stockbrokers in the same way as for any other company share.

The selection of investments for the trust and the general management of the fund may be undertaken by an in-house team of investment managers who are employees of the trust (a ‘self-managed’ trust), or the investment management task may be handed over to external managers. Most are externally managed. In addition to the 380 or so investment trusts, around 100 investment companies are venture capital trusts (VCTs) which are given tax breaks by the UK government to encourage investment in small businesses not listed on a stock market. (See Chapter 17 for more on VCTs.)

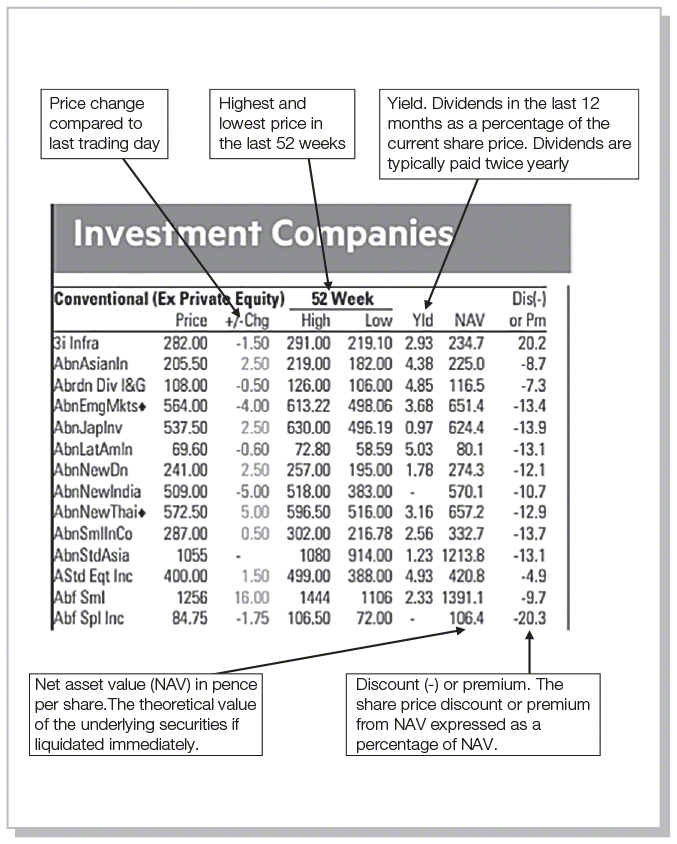

Discounts and premiums

There are two factors influencing the share price of an investment trust. First, the value of the underlying assets owned by the trust. This is expressed as a net asset value (NAV) per share. In theory the trust’s share price should be pretty close to the value of the assets held. But in practice they frequently sell at a large discount to NAV – only a few sell at a premium to NAV. Discounts of 10–20 per cent are not uncommon and they have even reached 68 per cent. The main factor that drags the price below NAV is the lack of demand for the shares. Here is a typical scenario.

Example - Net asset value

In year X there is great interest in, say, eastern European smaller companies so an investment trust is set up and offers its shares (say, 50 million) for sale at £1 each. With the money raised, £50 million of eastern European company shares are bought by the trust. For the next year the underlying assets (all those shares in Polish companies, etc) do no more than maintain their value of £1 per investment trust share, and so NAV is constant. Nothing in the fundamentals has changed. However, enthusiasm for investing in these up-and-coming nations grows among the UK investing public. The investment trust shareholders who want to sell find that they can do so in the LSE secondary market at above NAV. New buyers are willing to pay £1.08 per share – an 8 per cent premium to the NAV.

However, in the following year a worldwide recession strikes and investors head for safe havens and pile into bonds and familiar shares at home. The NAV of the trust’s shares falls to 60p as prices plummet on the eastern European stock exchanges. What is worse for the investment trust shareholders is that sentiment has become so pessimistic about eastern European companies that they can only sell their shares for 50p. They trade at a discount of 16.67 per cent to NAV (10p/60p).

Discounts may seem to present an excellent opportunity: you can buy assets worth 60p for 50p. However, they can be bad if the discount increases during the time you hold the shares. As you can see from the last column in Box 5.2, the discounts can be quite substantial. The Financial Times publishes the share prices and NAVs of investment trusts (companies) daily on the ‘Share Services’ pages. Additional information about individual investment trusts is at www.ft.com.

While much of the discount on a typical investment trust is due to negative sentiment there are some rational reasons for shares selling below NAV:

- Investors may think trust managers are incompetent and likely to lose more value in the future.

- NAV is calculated after deducting the nominal (stated book) value of the debt and preference shares. In reality, the trust may have to pay back more on the debt and preference shares than this.

- Liquidating the fund incurs costs (contract cancellations, advisers’ fees, stock brokers’ fees) so NAV is not achieved.

- The NAV is calculated periodically and so might be months out of date – it could be that current investors are allowing for property market declines since the last valuation say.

While most investment trusts invest in stock market quoted companies there are private equity investment trusts which invest in companies not quoted on a stock exchange, either directly buying their shares or by placing the money with other fund organisations that invest in private firms.

Box 5.2 - Investment trusts appearing in the Financial Times

Source: Financial Times, 6 June 2019.© The Financial Times Limited 2019. All Rights Reserved.

Costs for the investor

When buying (or selling) investment trust shares commission will be payable to your stockbroker10 as usual when buying shares (see Chapter 4). There will also be the market maker’s spread between the buying and selling price. This is generally 1–2 per cent, but for less frequently traded trusts it can be 5–10 per cent.

The fund managers’ costs for managing the investments and for administration are charged to the fund, either against annual income or against capital. A typical ongoing charge figure, OCF, (or TER), including the costs of investment management and administration, directors’ fees, audit fees and share registration expenses, is between 1.3 and 2.0 per cent,11 but this excludes performance fees that managers sometimes take. Ongoing charges on some particularly low-cost equity-invested funds can be as low as 0.44 per cent, but most property-focused investment trusts and private equity investment trusts tend to cost north of 2.5 per cent. See www.theaic.co.uk for ongoing charge rates and performance fee rates.

Borrowing

Investment trusts have the freedom to borrow (unlike unit trusts or OEICs). Borrowing to buy assets is fine if the return on assets over time exceeds the interest charged. However, it is a two-edged sword. The risk associated with gearing up returns becomes all too apparent when asset values fall.

Take the case of our trust investing in eastern Europe. If it had sold 50 million shares at £1 each and also borrowed £50 million to buy £100 million of eastern European shares the NAV would still start at £1 per share (£100 million of assets minus £50 million debt owed, for 50 million shares). If underlying asset values fall by 40 per cent because of the fall in the Warsaw Stock Exchange, the net asset value per share falls dramatically from £1 to 20p – an 80 per cent fall – because the assets fall to £60 million, but the debt remains at £50 million:

| Value of eastern European shares | £60m |

| Less debt | £50m |

| £10m | |

| Net asset value per share: £10m/50m = 20p | |

You can see why trusts that borrow a lot can be very volatile.

Tax

Capital gains tax is not payable by a trust on gains made within the trust. The income received by the trust is taxed, but then shareholders receive a tax credit to reflect the fact that tax has already been paid. Shareholders pay capital gains tax on the sale of their IT shares in the normal way (see Chapter 17). ISAs or a personal pension can be used to hold trust shares. Stamp duty of 0.5 per cent is payable when buying IT shares.

Split-capital investment trusts (‘dual capital’ trusts)

Around the turn of the millennium many perplexed trust shareholders lost a lot of money on split-capital investment trusts, largely as a result of not understanding the nature of the financial instruments they had bought. In the late 1990s they were often told that ‘split’ shares were some of the safest you could buy. The reality was that many of these shares were highly risk-loaded.

Split-capital trusts simultaneously issue different types of shares – the shares are ‘split’ into different forms. Generally, they offer income shares that entitle the holder to receive all (or most) of the income from the investment portfolio, such as dividends from underlying shares, and capital shares that entitle the owner to receive all (or most) of the rise in the capital value of the portfolio over the life of the IT, but not to receive dividends. Splits have a specified number of years (usually fewer than ten) of existence so that the capital shareholder knows when these shares will pay out (and the income shareholder knows when payments will cease).

Income shares offer a relatively high income to compensate for the low predetermined sum that will be paid at the end of the trust’s life when the shares are redeemed (some pay the initial amount back, some may only pay 1p at the end). The high yields on these shares seem very attractive to some people (the retired), but these investors must also weigh up the potential loss on capital value of the shares. For example, a £1 share that offers an income of 15 pence per year may seem good value, but not if the capital value is declining at 12 per cent per year. Also the income is not guaranteed and is likely to fluctuate from year to year.