CHAPTER 4

Life in boxes: the industrial formula for living

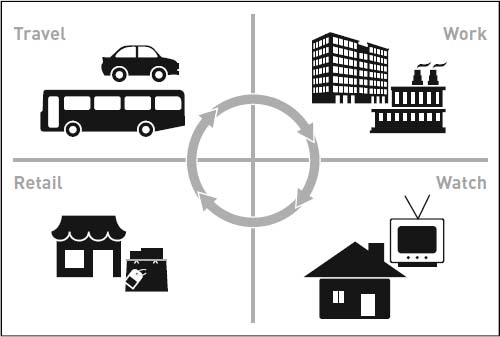

The post–World War II era in Westernised, developed and relatively democratic countries was a cosy existence, as cosy as any time in the history of humanity. Standards of living increased constantly, year upon year. Despite a few shocks and interruptions along the way, we had steady employment growth, increasing incomes and all the trappings that go with classic suburban living. It seemed as though this type of existence could be the answer people had been looking for. A decent-sized house with space around it. Close access to our place of employment. Government-funded schools nearby. Shopping malls filled with shiny gadgets we didn’t know we needed. A quarter-acre block with a driveway. A lush, green, grassed backyard in which to play with growing families. Actually, it sounds pretty damn good. I still think it’s an incredibly deluxe way of living, especially compared to the nondustrial alternative. It was predictable and packaged. I like to call it ‘life in boxes’ and it looks something like figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 life in boxes

Here’s how an average week would go for suburban dwellers between 1950 and 1995: wake up; get ready for work; hop into your transport box — a bus, a train, but more likely a car — and sit in that box for up to an hour. In that box, we’d listen to songs on the radio chosen by someone else in the hope that we might buy the album (which, incidentally, usually only contained three good songs out of 12, but was a terrific way for music stores to garner $30 revenue). In between the songs we’d be told by way of advertisements about other amazing products we could buy once we’d finished our work for the week. We’ve got to spend our money on something, right?

Then we’d arrive at our second box for the day. This was either a factory or an office. Of course, everyone hoped to graduate to an office from the factory floor, but either was fine as we were better paid than our parents and our parents’ parents. Better conditions too. We’d do what we were told in this box and make sure we helped our employer ship out its little brown boxes of goods for sale at the end of the day. The objective of working was to get to be in the corner box — a pretence of privacy for corporate dwellers with the primary objective of company cost efficiency — but sometimes we had to settle for the cubicle-style box. Many would try to be the last to leave the corporate box, or ensure they left after their boss, to further promote their corner-box aspirations. It was also vital that we had an empty ‘in’ box or pigeonhole box pre–desktop computer. Leaving the factory or office box late had the additional benefit of fewer boxes on the road in the race back to the suburbs.

We’d get back to our family box at the end of the day for a bit of rest and relaxation. Dinner would be cooked using many labour-saving, pre-packaged food boxes. Since the commencement of the 1980s we’ve had a little microwave box to save time, important, given we stayed so late at the corporate box while chasing the corner box. We’d eat and then sit down for a night of curated entertainment on the television box. Sure it’s flat now, but it’s a box that owned most families for hours a night for decades. In my country (Australia) we had four choices of what to watch. The box would entertain us. More subtly, it shaped us and our opinions and told us what we should buy from the big box retailer.

On weekends we’d visit the retail box hoping to see the objects of desire that we saw on the entertainment box that week. We’d hope to see something we didn’t expect that would provide us with new consumption opportunities of delight. We’d buy from the big box retailer what we could — or couldn’t — afford. We’d buy it because we’d worked so hard in our employee box that it made all the effort worthwhile. It was a reward that got us through the week. It gave us something to look forward to between the drudgery of following orders. We needed and deserved these things.

Our whole economy was designed around these boxes as our world rapidly transitioned from the simple industrial economy into the great era of conspicuous consumption. We didn’t just live in and around the boxes, we helped build and fill them. There’s a very good chance we worked for one of the companies that created the boxes: transport, housing, consumer goods, retailers, media, durable goods. It makes me wonder if we had a perverse yet subconscious need to facilitate our life in boxes by telling ourselves to buy more of something, forgetting the need the boxes served and instead allowing the boxes themselves to become the need. By knowing at a level that the more stuff we bought, the more we facilitated our so-called improved living standards. We raced the Joneses to have more boxes, but we and the Joneses both knew that the benefits of the race to have more would be shared regardless of the diminishing returns of box living.

It was obvious to me that we’d reached the end of the line when self-storage boxes started to appear across the Western world. In the US alone, self-storage generates annual revenues of more than $24 billion, and it’s been the fastest growing segment of commercial real estate for the past 38 years.1 At first I thought this may be due to the rising cost of real estate in our primary place of residence and the increase in apartment living. Yet 68 per cent of self-storage-box occupiers live in free-standing houses and 65 per cent even have a garage. This is an industry that only exists because we’ve decided to consume to such an extent that we need to outsource our excess. Another classic reminder of our back-to-front boxed lives is the irrationality of the garage. It’s not uncommon to have a garage filled with once-loved, unneeded superfluous stuff worth next to nothing while the new and relatively expensive car stands on the street instead of in the garage. Yes, much of what came in the boxes was and is good, but the things we own are starting to own us.

All of this doesn’t even take into account the downtime created by the boxes, such as traffic, waiting in lines and having to be in a box somewhere. While we can talk all day about the impact the boxes have on our lifestyle, our finances and our economy, it’s the impact they have on our minds that matters most. During the post–World War II era of box living, our minds became boxed in by thinking that was defined by consumption and production. We allowed the purveyors of box living to own our thinking, to limit our desires and output to what fits in the box and to turn us into box zombies. Our society developed a volumetric mindset, where more of anything was better. And the boxes made this possible.

Parasocial interaction

It’s not surprising that this lifestyle led to a number of weird human behaviours. Celebrity worship is one such behaviour, for which we probably can’t be blamed. People staring directly into our faces, talking to us in a very personal manner inside the box in our lounge room on a daily basis via the television is going to engender a natural human response. And that response is that we’re going to feel as though they’re talking directly to us: that we’re having an interaction of sorts and that it’s a real and valid relationship.

A term that describes this phenomenon is ‘parasocial interaction’. First coined by Horton and Wohl, parasocial interaction describes a one-sided relationship in which one party knows much about a person, while the other person has no knowledge that the party even exists. It’s easy to see how it happens. It’s interesting to prophesise why it’s happening. Is it a form of vicarious living? Is it people filling the void created by shallow daily corporate interactions? Is it that until television and radio arrived, storytelling was delivered via trusted family and tribe members? It’s impossible to know, but it does indicate that the one-way conversation provided by traditional media and life in boxes is something we were not designed to cope with.

The homo sapiens operating system

Just like computer systems, people also have an operating system (OS). It’s known as our deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA. DNA is a molecule that holds the code to our genetic instructions. It’s used for the development and function of all known living organisms. The DNA of homo sapiens is about 200 000 years old. Therefore our operating system is also about 200 000 years old. We haven’t had a software upgrade in some time!

And yet the world around us since the industrial revolution — a world that anatomically modern human beings have not been designed to cope with or adapt to via the evolutionary process — has changed rapidly. The evolutionary process moves quite slowly in relative terms. If we take industrial life as we know it today and divide the approximately 200 years we’ve been living this way into the 200 000 years we’ve been in our current human design, it only amounts to 1 point of 1 per cent — yes, 0.001 per cent of human existence. It’s a tiny proportion of our time on the planet, and if you ever feel as though you just can’t cope, it’s with good reason. Is any system ever designed in life or on earth to cope with events that occur 0.001 per cent of the time? No, it’s not.

The humanity externality

So it’s very ‘human’ to feel as though the modern world wasn’t designed for us, even though it’s the result of our behaviour. We’re social creatures in nature. Our ability to communicate and our social structures are key reasons why we sit atop the food chain on earth. But the industrial world was in many ways antisocial, driven largely by the rational and logical requirements of a system that places efficiency above all else. A loss of humanity is the price the system pays — an externality that’s spat out by the industrial machine as it forges ahead.

The shallow social pool

The time we invested in living in boxes changed the social structure of who we spent our days with. We’ve all had times in our lives when we’ve had to work and trade with people we don’t truly care for. Large tracts of our daily social cohort were filled with people we wouldn’t choose to invest time in if it weren’t for economic reasons. In other words, while it may not be our choice to have personal interactions with the people we work with, it’s necessary for survival. However, this takes up a lot of our time, leaving only so much time available for real human interactions of our own choice.

Dunbar’s number

Social researcher Robin Dunbar contended that we can’t have meaningful interactions with more than 100 to 200 people at any one time in our lives. Known as Dunbar’s number, his research suggested that there’s an actual cognitive limit to the number of stable social relationships we can physically maintain. This specifically refers to relationships where both parties know and can relate to each other on a personal level. Dunbar contended there was a link between the size of the neocortex and its processing capacity, which in turn limited functional group sizes. Proponents also assert that group sizes that become larger generally require more restrictive rules to maintain cohesion and enforce accepted group norms. In other words, smaller groups and those within the Dunbar limit can keep an organic structure, which is a structure of successful social relationships built around unwritten and unenforced social boundaries. Dunbar’s number isn’t about all the people we’ve ever met in our life, or even the people we’ve previously had periods of consistent contact with. It’s about our circle of close acquaintances in life at any one point in time.

As new people come into our social cohort, others — by physiological necessity — tend to drop out of our lives. People come and people go. It’s good to know that we no longer have to feel guilty about not calling up an old high-school buddy or an ex-colleague you bumped into at a conference. It affects us all, and it is largely beyond our control. The number of people any one person can maintain contact with does vary depending on their personal capacity, but the entry and exit of social relationships is a reality for all of us. It’s an interesting point to note given our ability to stay in touch, especially in a digital era that isn’t limited by technology or communication methods. The only limit we have on maintaining contact today is our personal ability to keep the lines of connection open. Yet, Dunbar’s number persists.

It’s also evident in internet social networks among people. Dunbar has recently been scientifically frolicking in the anthropological goldmine of Facebook and has revealed his early findings that digitally, as well as in the real world, our species is incapable of managing an ‘inner circle’ of more than approximately 150 ‘friends’ or meaningful social relationships.

Enemy territory?

Dunbar’s number is more about frequency of interaction than choosing with whom we’d like to interact. Many of the relationships that fill up our personal capacity have been designed by the industrial machine we live within, and the people we work and deal with on a daily basis. In the modern era these people are not always a function of who we like, trust and want to hang out with. Rather, they’re often the cohort that’s economically necessary but socially unpalatable — bosses, teachers and trading partners as opposed to the trusted family, tribe and community members who once made up our cohort. And as the industrial machine demands more and more of our time, we find ourselves in a cohort we wouldn’t choose if we stopped to design it. The reality of who we have our close relationships with is based on two physical realities: frequency and proximity. How frequently do we engage with other people? How often do we interact with them (all types of interactions, both physical and geographically displaced digital conversations)?

What is our proximity to a particular person? (In this case proximity pertains to the physical closeness and real-world interactions we have together.) Do we meet in person? Are we getting to know each other without the use of technology and by simply meeting in the same location?

The more of the above two things we have, the stronger our relationships become. If we think about who we have strong relationships with, we’ll see we have both frequency and proximity with them.

The thing we need to be careful about is that these facts point to the reality of how isolated we’ve become from those we care most about. If you’re a hard-working industrial participant, then it’s true that your co-workers have both a higher frequency and a higher proximity than any of your family members. We can only hope there are some people in the group we really enjoy being with. It’s probably why a lot of people take jobs — and leave bosses.

Digital clustering

In recent years, since the social web arrived, we’ve started escaping our geographic realities. Facilitated by these tools, there has been a classic emergence of digital cohorts based around shared value systems and interest. We can now choose the people we want to increase our frequency with even if we’re geographically constrained. Our permanent and daily digital connections enable us to circumvent our geography. We do a form of border hopping to connect with those we enjoy collaborating with, rather than collaborating with those who are merely profitable.

What evolves from here are displaced networks based on connection, creative intention and the new ability to collaborate digitally. It removes the previous demographic boundaries that shaped us, based on physical constraints rather than desired behaviour. When you were a child at school, you became best friends with the kid who sat at the desk next to you, and this seating arrangement was probably decided by alphabetical order of surnames (ironically, early web-based search engines were based on alphabetical order too, rather than the actual needs of the searcher). Or you became friends with your next-door neighbour, or other kids on your street, regardless of whether you actually shared any interests. While these options of friendship and physical connection still exist today, we’re not limited by them. There’s nothing stopping a 12-year-old gamer becoming best friends or a playing partner with another kid half a world away who shares a passion for the latest massive multi-player game. They can have all the frequency and interaction they would have had with their next-door neighbour playing a daily ball game in the yard just a generation ago. This is not just limited to the digital natives of the day; this reality is open to anyone, and it’s likely to become the norm in that we’ll choose desirable connections based on value systems and interests, rather than geographic constraints and economics. The shift in the type of work we do and the places we stay will start to represent what we first create virtually in the digital world. It will then eventually graduate to become part of our entire world, the one we shape in our own vision, first made possible by what these new digital connections afforded us.

Virtual is real

While it’s clear we’re living through a revolution, most people still create a weird kind of separation between what they call the real world and the virtual world, almost as though they’re two separate planets. It’s easy to understand why people feel this way. It’s because much of what’s arrived is so radical and new. It takes time to adjust to the new reality, but it’s still part of the single reality we all live in. Because much of the technology is so obvious and has changed human body language, the way we touch and interact with smartphones is a very different type of human movement, one not seen before. In this way it’s kind of clumsy and inhuman. This facilitates a human response that says, ‘This is not us. This is separate from us. We’re not used to it, nor that type of interaction from our species. So it must be a new world — a different one. We need to give it a new name so that we can segregate it while we work out how it all fits together and in our lives’.

IRL vs AFK

Since the web became a daily part of most people’s lives, the term ‘In Real Life’ (IRL) has been coined to let people know whether an interaction was virtual or physical. It’s a term hardcore netizens revile. They much prefer AFK, or Away From Keyboard, the inference being that the internet is real life — and it is. When we think about it, even this can only be regarded as a temporary descriptor for being connected at a point in time. Keyboards, like all technology, will eventually supersede themselves, and that process has already commenced. While high-quality voice recognition software seems to be forever promised ‘next year’, the keyboard has in many places been usurped. Most smartphones and tablets, while they have a visual replicator for a keyboard, are infrequently used. The user experience design high ground seems to be centred around making a keyboard an unnecessary interface. If we take it to an even deeper level, this distinction of being at some kind of ‘connected terminal or device’ will evaporate as well. Everything in our world — from packaged goods, to the windows in our homes — is on the verge of being connected. There will be no separation from the network unless we make a clear decision to ‘go dark’ in a distinct and purposeful manner.

netizen: a person who is a citizen of the internet (inferring that the internet has an expected set of collaborative behaviours just like our physical communities do)

Virtual is the physical preamble

From a social perspective, the displaced digital connections we make — those connections with people we’ve never met in person, or with whom we started a relationship digitally — are merely a preamble to a future physical interaction. We find that if we don’t enjoy a digital interaction with someone, we won’t continue the frequency of that interaction. If we do enjoy the digital interaction, then our basic human need for connection and physical contact will take over. We’ll find a way to connect with them, to meet with them and to break bread in the physical world. The digital interactions we create through our interest-based networks become a type of sampling campaign for meeting and interacting in the traditional human way: a way of finding souls who share something metaphorically to make it a physical reality.

Let’s go surfing

Often when I go surfing I take a photo of what the waves look like and post it on Twitter or Instagram. I like to let people know when there are great waves for surfing. When I do this I always add the hashtag #surfing. Some of my non-surfing friends (the large majority) like to live vicariously through my habitual and filter-enhanced picture of the beach.

I’ve noticed that this is also a habit of other surfers who live in my area. I live in Melbourne, Australia, which is more than one hour’s drive from the nearest breaking waves. For such a distance from the surf, Melbourne has a surprisingly large surfing population. I started to have some conversations on Twitter with other surfers who shared my passion. We’d first find each other by ‘surfing’ the hashtag of #surfing, and then we’d connect every weekend by sharing pictures of where we surfed that day. The crazy thing is, we’d all be leaving the same city, around the same time, to go surfing in many of the same places, but travelling in separate cars.

A now friend, previous stranger and fellow surfer, Simon, would talk with me online about the surf forecast even before the weekend arrived. He’d share with me where he thought the best waves would be and he became a really terrific resource, helping me enjoy my pastime more because he thought I might appreciate the information. And it probably made him feel good sharing his expertise because he could, not because he had to or had some financial reason to. Eventually we became comfortable enough with each other to organise a meeting at a particular beach to share some waves. I remember not knowing what he looked like (his profile picture was of a wave). He did tell me what car he had and his type of surfboard. In a way, meeting at a location and going in separate cars was a safety mechanism.

After a few surfs together we eventually started meeting in the city and driving from there to the beach in one car. We discovered that we share the same business interests and even work in the same industry. The new digital tools helped our like minds to find a cluster of relevance, a way to connect on what matters to us. It’s often the case that the tools we adopt say more about the values and experience we hold and the life we lead. Simon and I even share the same family circumstances. We’ve become good mates and we do various business projects together.

Digital replicates physical

The process I’ve just described replicates the exact way we connected with people before the digital possibilities. A certain topic would come up in physical conversation. We’d share some ideas. We’d talk about meeting around that topic, catching up and focusing on the issue. It’s exciting to meet someone who cares about what you care about. We’d agree to catch up at the next event for the topic of interest, then we’d do that thing together, and finally form a relationship beyond the thing, and delve into the human side of connection. It’s all the same behaviour, just being started via different tools. Our social patterns and norms are unchanged; just the tools are new.

Interacting is a human social need; it’s a deep-seeded need to connect and feel the warmth of a valued association. A virtual existence that doesn’t cross the physical chasm is a lonely one indeed. We have to remember that everything we invent needs to be invented with people in mind, regardless of the business or industry we operate in. The tools that enable us to be more human are simply becoming more important.

There is no ‘digital’

Digital tools and how they change what’s possible have created the birth of a new set of jobs that often have the D word (digital) in front of them. New types of jobs are one of the good things that come with disruptive change. They replace redundant jobs such as ‘woolly mammoth hunter’. But it’s when these so-called new digital roles are generalist in nature that organisations have got it severely wrong. They behave as though digital is a separate thing, something we attend to and then close the door on. While it’s clear that the omnipresence of the world wide web has changed our business infrastructure, it’s not clear that most people understand the truth about digital as it pertains to business strategy. Here’s a simple phrase to help remind us: ‘There is no digital; there is only life’.

We seamlessly move among a variety of technologies during our day, as we have done since the beginning of time with all forms of technology. We don’t have a digital life and an analogue life any more than we have a ‘sitting on a chair’ life or a ‘sitting on the floor’ life. A chair is just a piece of technology, just as the latest shiny device in our pocket is. And it’s about time we started recognising that a digital strategy is a flawed one by definition.

digital strategy: a flawed and simplistic strategy that involves only the web-based parts of a business

All that exists is a strategy. And just like any good strategy, it ought to take into account all of the potential inputs and considerations of our business environment. A good strategy should be technology-agnostic. It doesn’t care about the technology of the day. It only cares about serving the market. A good strategy, then and now, only cares about achieving objectives via consideration of all of the methods at its disposal.

What’s your electricity strategy?

As I write this, successful companies are still littered with digital XYZs: digital marketing managers, digital strategists, digital sales managers … the list is endless. Just go into any job-posting site and type in the word ‘digital’. Everyone in business is in ‘digital’. If we want to participate in the new economy, we have to be in ‘digital’, just as we have to be able to read and write.

The days of digital strategy are over. The days of digital anything in a job title are over as well. They should never have existed in the first place. Anyone who doesn’t get digital, doesn’t get strategy. Any person or organisation that has not invested the time to understand and embrace the changes is saying, ‘We’re not serious about surviving the present-day upheaval’. Having a digital strategy is a bit like having an ‘electricity strategy’. It just doesn’t make any sense. Referencing the infrastructure in the direction means the focus is not where it should be; that is, on the customer.

The market doesn’t care when you finished school

Anyone who works in a strategic or marketing capacity in a business, and who does not understand and naturally integrate digital into what they do, is not keeping abreast of how things are changing. Even worse, it means that the leadership team within the organisation that commissions these new roles is also out of touch. It’s incumbent upon management and staff to self-educate. The fact that all this stuff arrived after we graduated from university is not an excuse anyone will buy. The cost of not being across digital is just too high. It’s ironic given how easy it is to learn all the new ‘stuff’. None of it is hard. None. Yes, the technophiles took a while to get their act together in making the technology easy enough for us to use, but they got there in the end. Every tool on the web worth using for business includes a personalised hand-holding process that teaches us how to use it. It’s super marketing really — something VCR manufacturers could have used in 1981, and many remote-control designers could do with even today as you can see in figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 a remote control

If you can turn on a computer and read, then you can learn anything you need to know for business use in digital. The new landscape — that is, the new technological, internet-based economy — even comes with simple-to-follow learning instructions in the shape of online videos and user-friendly interfaces. We need not know more than how to read and how to be a human being to learn how to use the tools to a ninja level of effectiveness. It’s a terrific reminder that this revolution is one of connection, not technology. Technology is merely the facilitator.

Getting your digital on

It’s important to note here that I’m not talking about the deep-level digital skills required for, say, building a smartphone app. I’m talking about the knowledge needed by people who are in a similar job now to the one they had before the digital revolution arrived; that is, the generalist business and marketing executives of this world. Generalist business people don’t need to convert their entire skill base to become code monkeys or development engineers. We don’t need to know what makes the tools work, we just need to be able to use the tools. We only need to drive the metaphorical digital car. In business we only need to be concerned about whether the tool can get us to our desired destination, not the mechanics of what makes it possible. We can leave all that to the people providing the tools.

It’s not my job

A simple argument for any business executive is that their job is to manage people, strategy and finance, not be an expert in managing a bunch of tools. The problem is that business and tools are inextricably linked. Tools mattered just as much in production during the agrarian era as they did in the industrial era, as they do today.

Let’s take the example of a job type we all understand, that of a general practitioner (GP, or doctor). What they do has been impacted as heavily by technology as any business, maybe even more so. When we want to get diagnosed, be advised of the latest treatment options or be prescribed medicine by our doctor, we expect that they are up with the latest technology available to us as their patient (or customer). If a doctor told you during a consult that they didn’t bother to learn about MRI scans because it happened after they finished medical school, and they preferred to only rely on x-rays, you’d go and look for a better doctor pretty damn quick, one who cares enough to learn what they need to know.

Welcome to med school

The cosy period of being able to work at a stable job — a job that doesn’t change much for your entire working life — is over. While there will be times when we have to call in a specialist, we still need to know which one is best, and what they should be able to do and solve, as doctors do. We’re all general practitioners in our own industry, so it’s a requirement of the marketplace that we’re familiar with the latest tools and methods we need to achieve the outcomes we need for our business, regardless of when these tools arrived in the marketplace. The new general practitioners of business need to make the decision to keep up, just as doctors must with their journals and conferences. There’s no choice. It’s what the new market demands; every youngster entering our industry keeps up to date by default. It’s not even a task for them; they enjoy it. It’s the world they were born into. So unless we decide to enjoy it too, and go for deep learning by using the tools, we’ll not only be left behind, but probably replaced.

Now that we’re escaping the industrial machine, it’s about time marketers realised that people are not interchangeable widgets and that they would rather be spoken to and about by a human voice.