CHAPTER 17

A stranger from Romania: building a real Lego car

Sometimes it isn’t until after you’ve gone through an experience that you realise what you’ve just lived through, what it means and what it becomes an example of. I had an experience where I met a stranger from Romania. This is my personal example of the great fragmentation.

It started with the kind of request you get every day, a request for money from a stranger in a developing economy. He assured me he would put it to good use and that I would benefit from helping him. I gave him the money. He kept his word. It wasn’t really what anyone expected — including me. But yes, there’s more to it than that.

A new low for the internet

The first request from Raul Oaida to connect wasn’t one you get every day. His request-to-connect message on Skype said, ‘Hi, I’m building a spaceship’. He had me right then. It’s not every day you get a request to connect online with such an old-school kicking copy line that has such cut through. So I clicked on ‘accept’. Who wouldn’t? I thought maybe he’d been reading my thought-leading blog posts, or seen some of my startups or published articles. But the sad truth was that he was far more savvy than that. He wanted to connect with famed technologist, venture capitalist and trained astronaut Esther Dyson.

Through some diligent online investigating, Raul discovered I had a tenuous connection to Esther. We were connected via LinkedIn and Twitter as we’d met at the WPP Stream Conference (the world’s biggest media-holding company’s digital event). She was a board member of WPP and I was in a senior position at one of their advertising agencies. Raul wanted to use me to get to her. Mind you, he did in the end get to meet Esther in person. But I have to say it was a new low for the internet: astronaut-stalking via social media! He wanted Esther to invest in a rocket project he had concocted called Project October Sky. His plan was to build a suborbital rocket for about ten thousand dollars using some new techniques, just because he thought he could.

He finally connected with Esther (he found her email via other means) and she answered his email, but decided not to invest. He didn’t give up. In fact, he told me he had sent the same Skype request to more than 100 other investors and technology pundits before I accepted.

Digital tenacity

I quickly learned that Raul doesn’t give up easily. After others declined to invest, Raul started asking me to back his project. I told him I was small fry in the world of venture capital and technology, but he just wouldn’t go away. Every day, the moment I logged in online I’d hear that little sound Skype makes when you receive a message — ‘whooooop’ — mere seconds after I was connected. It was as though he was waiting for me or had some kind of alert already set up. Mind you, this would be around midnight in Romania. So we started chatting on Skype every other day. I quickly learned that he’d already done some projects that proved his technical capabilities, if not tenacity. He’d already built a small jet engine in his backyard, a steam engine from a bicycle pump, and he’d learned to fly a plane. He could get stuff done. He was starting to turn me into a believer, not because of what he said, but because of what he’d already done. He showed me the proof via the live video chat over Skype and his YouTube videos. A few short years ago, none of these tools existed so he would have had no way of proving himself. He also sent me his PDF plan of Project October Sky.

Marketing rocket science

I concluded I couldn’t really justify investing $10 000 into the project, but advised Raul I’d be happy to do something smaller together such as a minimum viable product if it could benefit both of us. He came up with the idea of sending a helium balloon into the near space field. He told me we could get more than 30 000 metres into the sky and film the curvature of the earth for under $1000. He went on to tell me that he wanted to do it for scientific and experimentation reasons, and that I could take on the marketing. In simple terms, if I’d fund it, he’d give me the filming rights and the decision on what to send up into space and film. I was surprised we could undertake the project so cheaply considering almost half of the cost went into purchasing a GoPro camera.

So I added a bit of marketing rocket science to the project plan. It’s the oldest trick in the playbook and is known as borrowed interest: attaching the activity to something with pre-existing fan bases. I decided we should send a Lego space shuttle replica into the near space field to pay homage to the end of the space-shuttle era, albeit in toy form (see figure 17.1). This would ensure that we’d get every space-shuttle fan and Lego fan to view our project.

Figure 17.1 anyone can get into space

It’s not even ironic that a teenage kid from Romania and a marketing guy from Melbourne could put an object into space, more than 30 000 metres high, film it and retrieve it on earth for a little over two weeks’ average Australian wages. Our final cost was a little under $2000. About ten years ago this would have cost more than $100 000 to undertake. A high-definition camera that could withstand the knocks and temperature variations would have been totally out of reach. The GPS device we used cost a mere $39. We even bought the helium balloon on eBay from the US and had it shipped to Romania — an impossible task in a pre-web world. It’s little wonder the real innovations in the revised space race are coming from private operators as their relative costs are also in rapid freefall.

The project gave us global attention. The video spread virally on YouTube and it also earned mainstream media coverage. Millions of views online has become a bit of a calling card in much the same way as Ivy League school MBAs did in the past. I’m of the opinion that one view of a technical or business project is worth 10 views of a funny cat, mainly because it leads to something. It’s a trajectory rather than a distraction.

The Super Awesome Micro Project

In order to leverage the momentum, we thought we’d do something to take it to the next level. We came up with the idea of building a full-size car out of Lego. It would drive and have an engine made out of Lego that ran on air. While this sounds kind of crazy, we knew we could do it before we even started. It was a classic marketing hack because all of the parts that made up this project already existed. It was just that no-one had put the parts together in this way before. People had built full-size stationary or ornamental cars entirely from Lego. People had built little engines out of standard Lego pieces from the technic range, and pneumatic engines had been built before. We’d even seen a very small one made from Lego online. The art was in re-organising these pieces to create new meaning. Yes, it would take money, time, skill and planning, but it was there for the taking.

We costed up the project and came up with a budget of $20 000 to do it and an estimated lead time of three months, both of which turned out to be a fair bit off the mark. But I truly believe that if people didn’t have the innate ability to underestimate the cost and time of projects we’d still be living in caves. We should be thankful human nature is so naïve when it comes to project estimations or we’d never undertake them. I wasn’t sure I wanted to invest that amount of money into building a giant toy car for an adult, so I decided to use my personal network to crowdfund it. Given the investment was a techie-hacker style project with no clear return on investment or product, it was even too radical for crowdfunding websites. So I went to Twitter (see figure 17.2). With a single tweet I raised $20 000 from 40 local patrons, all non-millionaire, everyday people participating in the technology revolution.

Figure 17.2 the pitch tweet

I also released a faux prospectus to send through to them that was designed for advanced people just like them. It didn’t even tell people what the project was. Half of the people who invested did so without any more information than what they got from the pitch tweet.

The fact that I funded this project so easily is an indication of what reputation from previous projects and personal brand can do, even at a micro level. Speaking of micro, I called it the Super Awesome Micro Project, a counter-intuitively long brand name that everyone liked and remembered. In a world where everything is becoming smaller and sound-bite oriented, it felt like the juxtaposition of a ridiculously long project name would serve the purpose of providing a mnemonic device — a little bit like ‘supercalifragilisticexpialidocious’. The name made people curious enough to call me to find out more. It was here that the pitch came into its own. When they asked me why they should invest in our air-powered Lego car for no return on investment, this is what I gave them:

During the height of the GFC the three heads of the largest car companies based in Detroit boarded private jets to fly down to Washington to beg congress for money. They did this because they didn’t know what the future looked like. And here we are crowdfunding an ecofriendly car made from toy pieces, built by a teenager in Romania. Boom! That’s what the future looks like. So join me and let’s be a lesson to an industry.

Sure there’s a fair amount of hype in this one. But every person who heard it put up some money to get involved.

Raul then invested the best part of the next 18 months bootstrapping the promised outcome of a drivable Lego car. There were no technical blueprints, no technical assistance from qualified engineers and no help from anyone. He did it himself near on 18 hours a day. Everything he knows about technology he taught himself from what he could read on the internet or watch via online videos and that great self-educating device known as YouTube. He learned on the job, a clear reminder that fragmented informal education is becoming a powerhouse for generating high-calibre people. It takes education to the next level of democratisation, beyond what public schooling did. Not only does anyone with web access have the potential to learn anything from the world’s greatest minds, we can now choose our own syllabus.

Once Raul had completed building the life-size car we shipped him and it to Australia to meet its makers, the patrons who supported him and made it possible. Getting a visa for Raul to enter Australia was no easy task. Romania is regarded as a high-risk country for illegal immigrants. Our first couple of applications were rejected by immigration because of his unique status of not being a student and not technically being in paid employment. It wasn’t until we applied for special consideration that we were able to get a work visa. This serves as yet another example that the formality of the industrial governmental structures does not serve well a world of pan-global startup projects and border hopping.

By this time the budget was clearly blown. I’d invested more than 100 times my original expected personal allocation of funds, granted that the outcome was grander than our initial vision. It ended up being a 3-metre-long Hot Rod capable of 20 kilometres per hour with a 100 per cent standard Lego piece pneumatic engine. And yes, we had to rebuild a significant portion of it in Australia. Let’s just say the car has some naturally occurring crumple zones.

We eventually got the car working and did a test drive to create some footage of the beast in action. We launched the Super Awesome Micro Project to the world with a short web video on YouTube. Just search for ‘Life size Lego car that runs on air’ to watch it. In order to maintain some symmetry to the project commencement, I launched the car to the world with a single tweet in reply to the original crowdfunding tweet. It was the only promoting I did to get the video underway. The other 40 patrons then retweeted my tweet and we uploaded the YouTube video to a homepage with some background information. That’s it. For a brief moment it became a global phenomenon, achieving millions of views in a very short period and featuring in all forms of news around the globe.

The marketing high ground isn’t just about what you’ve built; it’s also about the way you built it. It’s the angles of interest it creates. That’s what drives attention in a world that’s deluged with data. The Super Awesome Micro Project had many angles to it. They included:

- A connected world. Pan-global projects are only possible in a post-internet world.

- Globalisation. A digital world enables people to circumvent nation states with broadband cables. It eliminates physical boundaries.

- Technology. Projects that are heavy in the use of technology get more air time now. Just review the business and the technology sections of Forbes, The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times. The overlap of stories in these two previously separate sections of interest tells the story.

- Social media. It used the new media tools of connection. The story came from the people first and then graduated into the mainstream media second. The mainstream media now feeds heavily from the micro media.

- Building with a toy. The fact that the project was constructed with a ‘kidult’ toy inspires deeper age-agnostic engagement.

- The age gap. A teenager and an adult teaming up on a hacker project is an example of the evaporating accuracy of demographic profiling.

- Teenage genius. If we throw the word genius and the word kid into one sentence, it always equals free media.

- Crowdfunding. A rapidly growing space that gets more than its share of attention. The industry itself looks for examples to prove how it’s responsible for changing the landscape.

- The car industry. When an industry is struggling, any form of innovation (regardless of its usefulness) is used for comparison stories. The Super Awesome Micro Project was covered in car media channels the world over.

- Environmentally friendly. Examples of different forms of energy production and usage, especially pertaining to transport, even if the technology is very old (in our case pneumatic engines), provide a platform for reporting and debate.

- The maker movement. As the web graduates from virtual to physical, the maker movement and manufacturing 2.0 seek out people using lean methodology to make things and undertake projects with physical output.

- New web tools. Whenever I talk about this project to the media, I remind them that all of the tools we used to connect upon and to manage the project with did not exist 10 years ago. It surprises many people.

- Developed world meets developing world. It was highly unlikely that I would have met Raul. When I was his age our countries lived at opposite ends of the Cold War. The fact that it’s the uptake of collaborations among individuals to close the income gap with developing nations tells us much about the power shift from the few to the many. I knew it would get all the attention in the world so long as we could get the car built and operational in the way we intended.

If you’ve got a project launch right (in terms of a media hack or something with a launch mentality) it should only take a few hours to determine whether or not it’s going to work. Videos that are getting shared a lot and starting to go viral on YouTube often have a view count that stops at 300 or a bit above that number. To quote Google, the owner of YouTube:

Sometimes you might see that the video view count isn’t showing all the views you expect. Video views are algorithmically validated to be fair to both content creators and advertisers and to maintain a positive user experience. This process assures that the video views are quality views …

A viewcount that’s frozen at 300 is one of the great success indicators of a project being launched through YouTube. It means it’s being viewed so often, and shared so frequently, that YouTube has to check that nothing dodgy is happening. This is something every launch should hope for. It means the project has probably gained the attention it desired.

The hourglass strategy

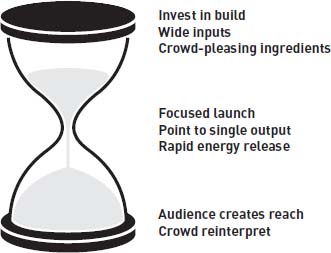

When considering all the launch elements that went into the Super Awesome Micro Project, it made me realise that the shape of launches needs to look different. The funnel has long been the visual marketing reference of how to launch a product. First, the funnel was referenced for wide-birth marketing and communications campaigns of multimedia output, all pointing at a single thing. It was then spoken about in terms of being flipped and letting brand evangelists do the talking for you. But both of these launching methods feel too limited to me. Good launches now look like an hourglass in shape: I call it the hourglass launch strategy (see figure 17.3).

Figure 17.3 the hourglass launch strategy

In simple terms, we need a lot of inputs that are notable: things worth talking about, points of interest. We invest our capital in producing these at the expense of launch and promotion costs. This is the top half of the hourglass. This is the stuff that really matters in a world of excess supply and a connected populous.

Then we launch the product itself. We take it to the market as it is, in its pure, natural state. The energy is focused on a single point of interest or distribution.

And from here the market decides how worthy the product is of its attention, time, spreading, interpreting, mashing-up or even that other financial implication of actually purchasing the product.

If what we’ve taken to the market is deserving, its exposure widens. The market takes it to the places where it deserves to be from a communication and awareness perspective, but very often from a distribution and collaboration perspective as well. The attention it earns opens up commercial opportunities as the connected world seeks out methods to leverage the output. People arrive on our digital doorstep wishing to distribute it, sell it, license it, adapt it and build it. The number of amazing outputs post-launch are the metaphorical equivalent of the number of amazing inputs we put into it pre-launch, which is something a heavy promotion campaign will never deliver. This is even evidenced by what happens to amazing advertisements without an amazing product to match. The advertisement is what gets built upon. The advertisement gets the parodies and mash-ups, not the product itself.

If the hourglass strategy doesn’t work, the world probably doesn’t need or want what you’ve given it. Before we decide on any launch, it’s worth remembering we live in a world where what we create is most often above the layer of necessity. And as with the 300 YouTube views, when we get it right, we often know within an hour as well. This is a classic lesson for marketers trying to promote something. If they focused more energy on creating something amazing, and less on trying to tell an amazing story about an average product, they’d find they get more attention. They’d save an enormous number of marketing promotion dollars.

A real flip has occurred in the post-industrial marketing landscape. Most times large organisations put their investment in the wrong place. They invest large portions into trying to tell an inspiring story about an average product or service. Instead, they should be investing more in making what they’re selling and letting the digital conversation take it to the world. What’s strange is that if we have an amazing advertisement that people love, the advertisement becomes the thing of interest, not the product it’s meant to serve. Maybe people find the advertisement entertaining and inspiring, and want to share it with everyone they’re connected to. They want to ask people if they’ve seen it and talked about it. In this instance, the advertisement becomes the actual product because it achieves the attention that the product should have received. But that’s not the point because it’s the product that the advertiser is trying to sell. I like to refer to this as the Super Bowl mentality. When people say, ‘that’s a great advertisement’ I have a couple of questions for them:

- What brand was it for?

- Are you going to buy it?

Unless we have a name and a yes, the advertisement is less than great. It may well be entertaining and worth remarking on, but advertising is not cinema, regardless of how many creative directors may try to extract budgets to make it so. Its primary purpose is to inform and change behaviour or, heaven help us, actually sell something. If it doesn’t do that, then it hasn’t done its job.

The human motive

Neither Raul nor I give a hoot about cars or Lego. They’re both tools for proving a point. A lot of people ask me what the commercial outcome of the project was meant to be. The answer is that there wasn’t meant to be one. The desired outcome of the project was the project itself; that is, the fact that we wanted to do it and we did it. While we knew it could have commercial benefits, they were symptoms, not reasons. Now that we want for nothing in developed countries, now that we have everything we need physically, it’s the emotional output that matters most to people. It’s passion projects that keep us up late working with a smile on our faces. They actually always mattered the most. It’s just that we’re starting to remember that and our economic circumstances now enable it. It’s this idea that creates gifts to humanity in the technology age. It’s why resources such as Wikipedia, Linux or even the blogosphere exist. It’s about people who have undertaken projects to create value for others, often to the point where they set up platforms that others can make fortunes from. The gift Sir Tim Berners-Lee gave the world with the world wide web itself has been the platform for some of the quickest and biggest fortunes ever created on planet earth. It’s the real human needs of connection, collaboration and community that drive us; the need to feel valued, appreciated and wanted. And while many people mistake financial achievement as a means of filling that void, the smart money is on embarking on projects that aim for human fulfilment.

An open-ended strategy

There’s also a deeper strategic reason for embarking on projects with unknowable commercial benefits. It’s only when we explore without agenda and embrace randomness that serendipity can occur. When a person or business has the presence of mind to not believe it knows everything, only then can discovery occur. It’s high time business became more humble. In times when the future is moving so fast, often on unexpected trajectories, business would do well to resist the temptation to forecast everything and to allocate capital to pure exploration. I find it strange that we only tend to see this in the technology and natural resources sector, when the potential upside of discovery is just as dramatic in any field. It’s human to explore. It’s why we live on every corner of the earth. It’s during these explorations that new lands with untold wealth and never-before-seen natural resources were found. It’s obvious that exploration creates a more bountiful ecosystem than the profit imperative ever could. Yet, we tend to ignore it in most established businesses because it takes courage that most executives do not have, and that corporate cultures do not allow. If we focus on profit, then what we see is selling more of what we already have, and reducing the cost of what we already make and leveraging resources we already control. While these are all totally valid concepts, they rarely lead to new fields of endeavour and the profit of tomorrow.

In a world where anyone, including any kid, can use technology to do anything we have to ask who our corporate competitors really are. Is market share what we should be measuring?