In this chapter, I consider the third element of the project's context (Fig. 1.11), the people involved. The project is proposed to introduce change to deliver performance improvement, but not everybody in the organization shares the project's objectives. Although the project is intended to benefit the organization, it may not be beneficial for everybody in it; there will be winners and losers for most projects. In this chapter, I consider reactions to change in organizations, and then how to identify stakeholders and their reactions to the change, and persuade them to support the project. That includes the development of a communication plan to communicate with stakeholders. I also describe project teams, and the leadership of the project manager. Although more part of the project than the project's context, this is where people from the project's context become part of the project, and the project manager has to lead people in the context as much as he or she has to lead the project team.

There are fundamentally three potential levels of change within organizations measured by the way it can impact on people's lives:

Background change: All the time an element of background change is taking place: people retire or leave the organization, new people join; minor changes are made to existing products, production machinery, or computer systems. It is all part of life, and people accept it as natural. It can also be managed through the routine organization. The work is undertaken by giving a temporary assignment to somebody in the routine organization, not by creating a temporary organization to undertake it. This sort of change can lead to small levels of performance improvement within the functional organization, what in Sec. 2.4 I called habitual incremental improvement.

Normal change: Then there is the normal change that is the primary focus of this book. The organization wants to achieve a step-wise level of performance improvement that requires it to undertake a significant change, and that requires the organization to assemble a temporary organization, a project, to undertake that change. People do not view this as natural, and the emphasis is on trying to win support for the project and the change it is introducing.

Extreme, life-modifying change: Finally there is change that has a significant impact on people's lives, perhaps making significant numbers of people redundant, or requiring them to join new organizational units with significant impact on their working relationships. The required performance improvement requires significant structural changes totally changing people's lives. This sort of change has a significant emotional impact on people.

Vic Dulewicz and Malcolm Higgs,1 quoted in my work on project leadership with Ralf Müller, described later in this chapter, propose types of change, which they describe as relatively stable, significant, and transformational, requiring three types of leadership. For the purposes of this discussion, I would group all three of these into the middle level of change above; they are more than background change and less than life modifying. This classification relates more to the complexity of the change itself, than the impact on people's lives, though relatively stable change will be on the border between background and normal change, and transformation on the border between normal and life-modifying change.

I discuss the second and third levels of change further.

Normal Change

The issue with normal change is twofold: winning people's commitment to the change and getting them to internalize it as something they think is the right thing to do; and overcoming resistance. In reality, these are two sides of the same coin, but I want to discuss each separately because they highlight different issues.

Winning Commitment. The need to win people's commitment to the change is illustrated by the following quotation:

Every new idea goes through three stages:

1. First, people think it is stupid.

2. Then they think it is dangerous.

3. Then they think they believed that all along.

For many years I couldn't find where this quotation was from, but then in quick succession I heard three authors had used variants of it: Mark Twain, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Mahatma Ghandhi. For the second stage, Mark Twain suggested they think it is against the bible, and Mahatma Gandhi had a previous stage, that first they try to ignore it. However, when searching on Google, I could only find it credited to Arthur Schopenhauer. There is a science program on British television called Horizon, which, when discussing a controversial new scientific idea divides the program into three parts. In the first scientists are wheeled out to say how stupid the idea is, then they are wheeled out to say that if the idea gains credence they are going to have to rewrite all the text books and change what they have been teaching for 80 years, which they don't want to do. Finally they are presented, self-righteously saying it was obvious all along (see example 4.1).

Example 4.1 is light-hearted; it makes good television. The point is when introducing a change you must understand that people need to be given time to go through these three stages. Do not expect them to go in one step from hearing about a new idea, to internalizing it and accepting it as obvious. They need to have time to understand the idea and see why it is sensible and relevant to the organization's needs. Then they will begin to realize the impact on their working lives, and they may not like that. They need to be given time to deal with their concerns, and be shown the changes will actually be in the best interest of themselves and all concerned. Then they will accept the new truth as self-evident, and internalize and accept it. You need to help people through this process and allow time for each step.

Example 4.1 Three stages for a new idea

One Horizon episode dealt with the idea that Europeans had settled in North America about 15,000 years ago. The evidence was that early North American tribes had used a design of flint axe that originated in France about that time. This theory of course contradicted two established theories: that North America had been inhabited by people coming across a land bridge from what is now Russia through Alaska, and that the first wave of settlement was 11,000 years ago. Further, Europeans 15,000 years ago didn't have boats and so weren't capable of crossing the Atlantic. So the first third of the program was devoted to academics rubbishing the proposed theory. Then evidence was produced showing that there were two waves of people coming through Alaska, the first during an interglacial period 18,000 years ago, and then the second at the start of the current interglacial period 11,000 years ago, so in fact North America had been inhabited for 18,000 years, longer than previously thought. DNA evidence was then produced showing that some original North American tribes, especially from the East coast, had 15,000-year-old European DNA in them. The second third of the program was devoted to native North Americans saying they didn't want to be descended from Europeans because they hated what they did to them starting in the middle of the last millennium. Anyway, how did Europeans get across the Atlantic without boats? The clue there is in the word "interglacial." 15,000 years ago the Atlantic was frozen half way down and so they walked across. Well, that was obvious all along; nobody ever believed anything different!!!

Resistance to Change. I use two quotations to illustrate resistance to change. The first is due to Charles Handy3:

If you put a frog in cold water and slowly raise the temperature, it will allow itself to be boiled to death.

Handy uses this as a metaphor for people in organizations. They are surrounded by an environment that they find familiar and comforting. You come along and say, "We need to achieve performance improvement and so we need to change," and they say, "But we have done it this way for the last 5 years; it has been OK for the last 5 years, it is OK now." They cannot see that outside the organization they know and love the world is changing, that the business environment is beginning to boil. If you try to change people too quickly you will just get resistance.

When I first started working for Coopers and Lybrand as a consultant, I would go into client organizations and say, "What you are doing is wrong; you need to do it this completely different way." The reaction I would get from the directors of the client organizations would be that they were intelligent people; if their problems were so easy to spot they would have spotted them. But the problem the directors suffer from is they can't see the point where what they are doing goes from being OK to being a problem. Things change slowly and they cannot see the point where they cross that line from being good to needing to achieve performance improvement. I learnt a lot from my boss in Coopers and Lybrand. He would start by building a relationship with the client and winning the client's trust. Then he would begin to ask the client questions about how they thought they were doing. Well, they had called in the consultants because they had a sense of unease but were not quite sure why. So through a series of questions my boss would get the client to identify the problems for themselves and identify the solutions for themselves. In this way the client would have much greater acceptance and ownership of the proposed solutions.

Many Western managers hit their staff with logic, "You have to do as I say, because; because; because I say so." As long as 2500 years ago Aristotle suggested that you should start by building relationships with people. Once you have done that you can sell them your values and vision, the need for performance improvement. Once you have done that, then and only then can you persuade them with the logic of the best way of achieving the vision. The American President Ronald Reagan was very good at this; the British Prime Minister John Major always went straight in with the logic and didn't persuade people.

The second quotation I find useful is from Machiavelli4:

There is nothing more difficult to arrange, nor doubtful of success, and more dangerous to carry through, than initiating changes in a state's constitution. The innovator makes enemies of all those who prospered under the old order, but receives only lukewarm support from those who would prosper under the new. Their support is lukewarm partly from fear of their adversaries, and partly because they do not trust the new order until they have tested it by experience.

Machiavelli says that trying to introduce change is dangerous. Part of the reason is, as I said above, there are winners and losers from the change. The losers are trying to stop you from being successful. You might think that is balanced by the winners, who are supporting the change. But, no; the winners are sitting on the fence. They don't want to come out strongly in favour of the change, in case it doesn't work. They don't want to make enemies of the losers in case they win. So the winners sit on the fence, waiting to see what happens. So initially you are on your own.

Extreme, Life-Modifying Change

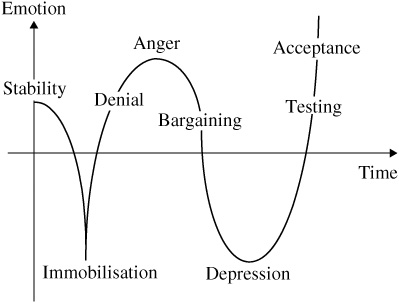

Extreme, life-modifying change leads to much more severe emotional responses (Fig. 4.1 and Table 4.1). The emotional response shown in Fig. 4.1 was first identified in people who have been told they have a fatal illness (Example 4.2), but it is now recognized that anybody going through an extreme, life-modifying change follows a similar cycle. This can include losing or even changing your job, getting divorced, or losing a loved one. It is relevant in a change context, when the change is extreme and life modifying, where people lose their jobs, or have to make significant changes to their working environment, such as moving location or suffering significant changes in work colleagues. Example 4.3 describes one such situation. Again the change manager needs to recognize that people have to go through these stages and need to be given time to deal with each one. Don't try to rush people to acceptance. Give them time to deal with their denial and anger, but try to help them through the depression stage quickly to testing and acceptance. Also the manager's style needs to change through the cycle. There is a saying (from Shakespeare's play Hamlet) that "you have to be cruel to be kind." It is not kind during the early stages to give people false hope. You have to make it clear through the denial, anger, and bargaining stages that there is no

FIGURE 4.1 Response to extreme, life-modifying change.

TABLE 4.1 Response to Extreme, Life-Modifying Change

| |

Stage | Response |

| |

Stability | Management communicate their vision, the need for change, and the consequences. |

Immobilisation | People are taken by surprise. Their reaction is anxiety and confusion. |

Denial | People defend themselves against the threat to their life or livelihood: "They can't mean me!!!" "Is that what we get for years of loyalty!!!" "Management is overreacting; it can't be that bad!!!" |

Anger | Openly displayed anger towards management emerges. People try to take control, through their power base in the organization, trade unions, etc. Alliances are formed; efforts to divide management are made; all means to reverse the situation. Management must persistently argue the case, and not indulge in warfare. |

Bargaining | People begin to try for a modified solution. All kinds of remedies will be proposed in order to try to reduce the impact of the change: "If we take a cut in salary?" "If we increase our productivity?" |

Depression | Frustration, and a feeling of having lost spreads. People find it difficult to work, and organizational paralysis sets in. Management must help. They must have plans containing supporting packages, and must actively assist individuals in taking responsibility for themselves in the new situation. |

Testing | The individual and the organization start working with alternative exit strategies to try to facilitate the individual's transition: "Did you say I could have 6 months pay while looking for a new job?" "Being paid through a year's MBA program would help the transition." Management helps to find realistic alternatives. |

Acceptance | Individuals and the organization deal realistically with the situation. They may not like it but they accept it. Management gives recognition and support towards future plans. New stability is achieved. |

| |

alternative, you are sorry they are upset but this is the way it has to be. If you give people false hope, and then have to let them down again later (as happens in Example 4.3), the second letdown will hurt more than the first (Example 4.4). It is better to be resolute. However, during the depression, testing, and acceptance stages, you have to be supportive, helping people test out alternatives for the future. Reversing the change is not an alternative, but there may be many other options. In Example 4.4, the military began to help the town to use the facilities in the redundant army base to attract new industry to the town. At the time of a major redundancy program many organizations set up an out-placement department to help redundant employees develop their resumé and seek new work.

Example 4.2 Homer's odyssey

There is an episode of the Simpsons where Homer thinks he has eaten the poisonous bit of Japanese fish. He rushes to hospital, and the doctor says he will be immobilized. Homer says, "I can't move." Then the doctor says he will go into denial. Homer says, "Perhaps I didn't eat it." Then the doctor says he will be angry. Homer says, "Why me?" Together they go right through the cycle. I had been teaching this for several years when I saw this episode and was amused.

Example 4.3 Parade ground management

There is a case study in a former book of mine of the Norwegian army shutting an army base.5 Based on a combination of the peace dividend at the end of the cold war and new technology the Norwegian government decided to halve the number of personnel in the army. This involved shutting half the army bases. The case study describes the shutting of the first base. Half the people working on the base were military personnel, half civilians. The military personnel would not be made redundant. The army was reducing numbers through natural wastage, with a very high churn rate. But the civilians were all redundant. Further, they represented about one third of the working population in the local town. Where you have a large employer like that, for every job in the base there is a job in the town: shopkeepers, doctors, taxi drivers. Two thirds of the jobs in the town are threatened. When communicating the decision to the base employees, the base commander assembled everybody, military and civilian staff. He said, "Base, attention! We are shutting the base. Military personnel, you will receive your transfer details. Civilian personnel, you are all redundant. Dismissed!" Before the meeting there was no inkling; the civilian staff were all stable. Immediately after, they were first immobilized. "Did we hear right? I think the commander said they are shutting the base." Then denial set in. "It can't be right. They must be shutting the base up the road." Then anger. "Why aren't they shutting the base up the road? Why us?" Then bargaining. There was a piece of technology on the base that accounted for about 40 percent of the operation, that only one other base in Norway had. The staff went to ask the base commander if that bit was shutting. He gave the wrong answer. He said he would check back with Oslo. This was interpreted as meaning that part of the base would stay open. When the answer came back, they were shutting half the bases in Norway, one other base in Norway has this technology, it would stay open, this one would close, the pain was greater than before as raised expectations were dashed. At about this point, as things were spiralling out of control Kristoffer Grude was bought in as a consultant, and a much more humane approach was adopted. He encouraged the army to work with local politicians and the unions to find options for the future. The base had to close but new industry could be attracted to the town.

Example 4.4 Being clear in the messages

When I worked for a company called Imperial Chemical Industries, ICI, in the early 1980s, they merged the two engineering departments in the northeast of England, and made one third of the staff redundant. There were two divisions in the northeast, Petrochemical and Agricultural Divisions, which used very similar technology. Each had its own engineering department and it was decided that this was a waste and the two would merge. About a month before the announcement was made a rumour began to circulate that this would happen, and half the staff would be made redundant. When the actual announcement was made that it was only a third, people's reaction was, "Phew, it was not as bad as we feared. That's all right then." We suspected afterwards that the directors had seeded the rumour of a half so people would be much more accepting of the actual announcement. When the directors were making the announcement at a staff meeting, they said, "Just to put in perspective what it means, look at yourself, look at the person on your left, look at the person on your right. One of you is going!!!" The communication was clear. About 5 years later a privatized company in the U.K. was making one in five members of its staff redundant, based on new technology and organizational changes. However, they thought that this number would be unacceptable, so they fudged the message and made it sound like 1 in 10. When it turned out it really was one in five, people were more angry than they otherwise would have been.

Figure 4.2 illustrates a stakeholder management process. I suggested in Sec. 3.4 that a necessary condition for project success is to agree the success criteria with all the stakeholders before you start. This process helps you do that.

Identify Interested Parties

A stakeholder can be defined as anybody who has an interest in the project, its work, outputs, outcomes, or ultimate goals. Table 4.2 contains a list of potential stakeholders. Most of these require no further discussion. The media can be very dangerous. A couple of years ago I did some work with a public sector organization which lived in fear of the tabloid press. If a project went wrong they would be ridiculed in the tabloid press. This is a competency trap (Chap. 17). They may have two ways of doing a project, an excellent way with a 90 percent chance of success and a mediocre way with a 100 percent chance of success. They would choose the mediocre way. If they chose the excellent way and were unlucky and the project went wrong, the tabloid press wouldn't say they did the project the right way and were unlucky. They would just say they had wasted public money on a failed project. They wasted public money doing projects certain but mediocre ways for fear of the tabloid press. The tabloid press aren't interested in telling the truth; they are only interested in selling newspapers.

FIGURE 4.2 Stakeholder management process.

TABLE 4.2 Potential Stakeholders on a Project

|

Potential stakeholders |

|

Employees (users, operators, bystanders) Management Shareholders Resource providers Customers (internal and external) Suppliers (internal and external) Neighbours Government (local, national, continental) Opinion formers (media) |

|

Table 3.1 shows that different stakeholders have different perspectives on the success criteria for a project. You need to identify the different views different stakeholders potentially have on project success. I said when discussing Table 3.1, that potentially the different success criteria are incompatible, and they will be if you wait until the end of the project to try to make them consistent. You have a much better chance of balancing the various success criteria if you negotiate agreement before you start the project.

Identify the Stakeholders and their Interests

From these two steps we are in a position to identify the various stakeholders and their interest. You can begin to compile the stakeholder register (Table 4.3).

Analyse Stakeholders

You are now in a position to analyse the stakeholders. You do that by asking three questions about each stakeholder:

1. Are they for or against the project?

2. Can they influence the outcome?

3. Are they knowledgeable or ignorant about the project?

The answers to these questions can be entered into the stakeholder register.

For or Against? There are three potential answers to this question: the stakeholder is for the project, against it, or they don't care whether it is successful or not. There are some contractors who don't care, just as long as they get paid.

Influence the Outcome? The stakeholders who are for the project and can influence the outcome are the ones you like. You want to encourage them. The ones who are against the project and can influence the outcome are the ones you don't like. You either need to try to reduce their influence, or change their opinion. Those who can't influence the outcome are not so important. With those who are for the project but can't influence the outcome, you might try to find ways to make them more involved. With those who are against the project but can't influence the outcome you might try to change their opinion, or you might try to ensure they have no influence. There is one other type of stakeholder who is quite dangerous: People who can influence the outcome but are for the project for the wrong reason. They will be trying to take the project off course to achieve their own covert objectives and not the project's overt or stated objectives. The technology manager in Table 4.3 may be like that.

SWOT Analysis. A strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis (or more correctly OTSW analysis) of each stakeholder can help you answer the first two questions. You ask yourself about each stakeholder, Do they view the project as an opportunity or a threat? If they view it as an opportunity, then presumably they are for it, and if they view it as a threat they are against it. Then you ask yourself what are their strengths and weaknesses. If they have strengths then presumably they can influence the outcome and you will be trying to reinforce the strengths of your proponents, those who are for the project. If they have weaknesses they won't be able to influence the outcome and you will be trying to reinforce the weaknesses of your opponents.

TABLE 4.3 Stakeholder Register for the CRMO Rationalization Project

There is a moral issue here. You might identify while doing the analysis that a stake-holder is in favour of the project but it is a potential threat to them: Do you tell them? My view is that if the project is mainly an opportunity to them, but there is a small potential threat you should openly discuss that with them, and try to solve the problem. If you don't, then when they find out (and they will find out) they will be against, but if you have tried to solve the problem then you may be able to resolve the issue. On the other hand, if they are for the project but you realize it is only a threat to them (they are going to be made redundant but they don't know yet) then you may try to keep it from them for as long as possible. When they find out they are going to be against the project, whether you tell them now or later. That is the moral issue, whether failing to volunteer information is being deceptive.

Knowledgeable or Ignorant? You need to think about whether the stakeholder is knowledgeable or ignorant about the project; think about where they are now and where you want them to be. I believe you should aim to be the first to tell people about the project. If they hear about the project as a rumour they will be against it. Their thinking will go something like this: "I heard about the project as a rumour, therefore management must be trying to keep it secret. If management are trying to keep it secret it must be bad, and so I am against it." Once somebody has decided they are against the project based on incomplete or incorrect information, it will be very difficult to change their opinion. It is a quirk of human nature that if people form an incorrect opinion based on incomplete or incorrect information, they find it very difficult to change their opinion later (Example 4.5). You want to be the first to tell them so they have positive opinions from the start. But you mustn't tell people too early; you need to clarify your own thinking first.

Example 4.5 Discovering one's own mistakes

Psychologists have done experiments where they have shown people pictures progressively out of focus, and ask them to identify the picture. In this way they establish how far out of focus the picture has to be before the subjects will get it wrong more often than not. The experimenters then show the subjects a picture well out of focus, and ask the subject to say what it is. The experimenters then slowly bring the picture into focus and ask the subjects to say if they want to change their minds. The pictures have to be brought well into focus beyond the point where the person would normally make a correct identification before they will change an incorrect diagnosis.

This happened in an incident on a nuclear power station at Three Mile Island in the eastern United States in the 1980s. On the plant there was one faulty instrument which should have been indicating a fault, but was not working. A second alarm started and the operators made what would have been a correct diagnosis of the fault based on the information they had, the second alarm sounding but not the first, and reacted accordingly. But it was the wrong diagnosis because they had incorrect information. A third alarm started which should have told them their diagnosis was wrong, but they continued to react according to their original diagnosis. The whole station started to shout at them, "wrong diagnosis," but it was only when the emergency team came in with a fresh perspective that they discovered the true fault and saved the situation. The operators were like the frog in hot water, about to boil to death.

Develop a Stakeholder Influence Strategy

There are several different ways of categorizing stakeholders to determine the influence strategy.

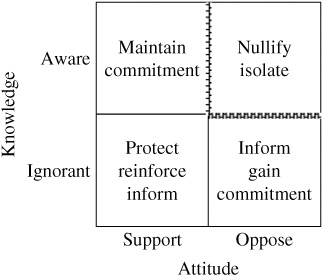

Knowledge-Support. The first is based on whether they are for or against the project, and knowledgeable or ignorant about the project (Fig. 4.3).

Knowledgeable-support: These people must not be taken for granted. You should continue to work with them and keep them informed about the project to maintain their support.

Ignorant-support: These people you assume will support the project when they know about it, but they are currently ignorant. These are the people that you want to ensure that they hear about the project first from you so they end up in the knowledgeable-support box.

Ignorant-oppose: These are the difficult people, people who don't really know what the project is about, and perhaps oppose it for the wrong reason. The problem is, people these days can hold very strong beliefs when in reality they are quite ignorant (Example 4.6). Example 4.5 suggests it is very difficult, and even impossible, to change their views. Another important issue is to talk to people in layman's terms, talk to them in terms they can understand (Example 4.7). If you want people to support you, don't blind them with science. Talk to them in their language.

Knowledgeable-oppose: These people are easier to deal with; they are against the project for good reason. You can either try to find a way of changing the project to win them over, or you need to try to isolate them, and make sure they can't influence the outcome.

Example 4.6 Strongly held opinions

When I was at Henley Management College, I had somebody to talk on my courses about stakeholder management who worked for a publicly owned company called Nyrex, which has the popular task of disposing of low- to medium-level nuclear waste. He worked for the publicity department and had the job of delivering lectures around the country. He related the story that after one lecture a woman came up to berate him for about 10 minutes. She told him that Nyrex was completely evil, that burying nuclear waste was completely wrong, and that the nuclear industry should be completely shut down. After about 10 minutes she asked, by the way, what does nuclear radiation look like? Is it green slime? She was completely ignorant. She had very strong opinions, gained from reading the tabloid press, but was completely ignorant.

FIGURE 4.3 Stakeholder management strategy knowledge-support.

Example 4.7 Talking in terms people can understand

A British mining company was trying to develop a uranium mine in Canada, and they were holding the public enquiry. This is conducted as a quasi court case, with the mediator in the chair and lawyers questioning witnesses. One of the company's engineers was in the stand, and a lawyer representing the environmental lobby mischievously asked him what would be the radiation level of waste water leaving the site. The engineers, as engineers would, gave a precise answer, six decimal places, so many becquerels. Of course, the press were in the court and heard this. The next day the newspapers were full of the story, the waste water leaving the site would be radioactive. The locals would all die of cancer; their children would all be born with two heads. The correct answer was the radiation level would be half that of rain water—this water would be twice as pure as rain water. Even rain water has a radiation level. The company immediately tried to correct the wrong impression. But it was too late. The genie was out of the bottle; Pandora's box was open. There was no putting the furies back. People weren't listening any more (Example 4.5).

Power-Impact. Another way of categorizing the stakeholders is by their power within the parent organization, and their impact on the project. This leads to four influence strategies (Fig. 4.4).

Support-Agree. The last way of categorizing stakeholders discussed here is by how committed they are to the goals of the project and how much they agree with the way they are being achieved6 (Fig. 4.5). The passives often represent about 40 to 60 percent of the stakeholders, and the way they feel about the project is usually influenced by the waverers. The waverers in turn are influenced by the golden triangle. You might think that the zealots are your best allies, but they just give unthinking support, which often does not help very much. The golden triangle, on the other hand, by questioning the project help to improve it.

Monitor Stakeholder Satisfaction

As the project progresses, you use the stakeholder register to monitor stakeholder satisfaction. If everything goes according to plan, then hopefully that leads to a successful project.

FIGURE 4.4 Power-impact matrix.

FIGURE 4.5 Leadership competencies contributing to project success.

If the stakeholders are not behaving as expected, you may need to change your influence strategy. Or something may happen which changes the stakeholders' views, and again you may need to change the influence strategy.

Table 4.3 is a stakeholder register for the CRMO Rationalization Project.

4.3 COMMUNICATING WITH STAKEHOLDERS

The next step is to develop a communication plan to communicate with stakeholders. Susan Foreman suggested that we need to market the project to the rest of the organization.7 When developing a communication plan there are several questions you need to ask yourself.

What are the Objectives of the Communication? The objectives of the communication may include

1. To raise awareness of the project and thereby gain commitment from key stakeholders

2. To inform other business areas and promote key messages about the project, particularly the benefit to the organization, demonstrating the planned performance improvement

3. To make two-way communication to ensure a common understanding of the project and its objectives to negotiate agreement with the stakeholders

4. To maximize the benefits from the project by having everybody working for its success

Who are the Target Audience? You need to research the organization to try to understand who are the key players, and their objectives. You need to understand how the organization works and what motivates people. You should have done some of this analysis in developing the stakeholder register. In particular, you need to segment the target audience. For different recipients of your communication, there will be different objectives, and correspondingly different messages, different ways of structuring the messages, and different modes of communication (see Example 4.8).

Example 4.8 Segmenting the market

The directors of British grocery chain Tesco felt that they were not communicating well with their staff. So they hired a firm of consultants to investigate why this might be. The consultants concluded that although Tesco segmented the customers for their products very well, designing different messages and different modes of communication for different groups, they treated their staff as one amorphous mass, and sent the same message to all of them in the same way. The consultants helped Tesco segment their staff into six distinct groups based on their lifestyle, and helped them develop different messages and different modes of communication for each group.

What are the Key Messages? The messages to be communicated need to be designed to achieve the objectives. Different messages will be designed for each segment of the target audience. The communication needs identified in the stakeholder register will help in the design of the messages.

What Information will be Communicated and by Whom? The messages will indicate what information should actually be communicated. Different messages are best sent by different people. The project manager may inform stakeholders about the scope of the project, and when various things will be done. But information about the desired performance improvement and the benefit to the organization are better coming from the project sponsor, or even more senior managers at key points of the project so they can show their commitment, and the importance of the project to the organization.

When will the Information be Given? Timing can be critical. You want the sponsor and senior managers to show their commitment early on. The project manager can take responsibility for the later communication. Also, as I have said, you want key stakeholders to hear about the project from you or the sponsor first, and not as a rumour, so they gain positive views about the project from the start.

What Mechanisms will be Used? A range of possible mechanisms are available, including

![]() Seminars and workshops

Seminars and workshops

![]() Press, television, and other media

Press, television, and other media

![]() Bulletins, briefings, press releases, Web pages

Bulletins, briefings, press releases, Web pages

![]() Site exhibitions

Site exhibitions

![]() Video and CDs

Video and CDs

Again you will choose the media depending on the target audience, the objectives of the communication and the messages you want to convey. Different types of information are communicated using particular types of channel, and different stakeholders will be more receptive to some channels than others.

How will Feedback be Encouraged? Communication should not be one way; you should talk with people, not at people. If you want people committed to your project and the change it will introduce, they must feel involved, and feel that they have some influence over the design. (It is important that they feel they have some influence, whether or not they actually do is not so important.) But for this reason it is important that you are seen to be looking for and listening to feedback.

What will be Done with the Feedback? So it must be obvious to the stakeholders that their feedback is being used. The best way of achieving this is of course to be seen to be answering the stakeholders' questions. Not straight away as they give their feedback in a way that convinces nobody that you are actually listening; but later in a considered way, perhaps by making changes to the design of the project, but particularly by incorporating responses to the feedback in later communications. If you incorporate responses in future communications it demonstrates that you have actually heard and remembered what was said, remembered well enough and long enough to actually incorporate responses into the later communications.

In forming the project team, the project manager brings together a group of people and develops amongst them a perceived sense of common identity, so that they can work together using a set of common values or norms to deliver the project's objectives. Charles Handy8 says this concept of perceived identity is critical to team formation; without it the group of people remain a collection of random individuals. What sets project teams apart is that a group of people, who may never have worked together before, have to come together quickly and effectively in order to achieve a task which nobody has done before. The novelty, uniqueness, risk, and transience are all inherent features of projects (Chap. 1). Because the team is novel, it has no perceived identity, ab initio, and no set of values or norms to work to. It takes time to develop the identity and norms, which delays achievement of the team's objective. Furthermore, because the objective is novel, and carries considerable risk, it takes time to define, and, if the project is to be successful, this must be done before the team begins to function effectively.

Team Formation and Maintenance. The process of forming a team identity and a set of values takes time. Project teams typically go through five stages of formation called forming, storming, norming, performing, and mourning.9 During these five stages, the team's motivation and effectiveness goes through a cycle in which it first decreases, before increasing to reach a plateau, and then either increasing or decreasing towards the end. The manager's role is to structure the team formation processes in such a way that this plateau is reached as quickly as possible, the effectiveness at the plateau is as high as possible, and the effectiveness is maintained right to the very end of the task.

Forming: The team comes together with a sense of anticipation and commitment. Their motivation is high at being selected for the project, their effectiveness moderate because they are unsure of each other.

Storming: As the team begins to work together, they find that they have differences about the best way of achieving the project's objectives, perhaps even differences about its overall aims. They also find that they have different approaches to working on projects. These differences may cause argument, or even conflict, in the team, which causes both the motivation and the effectiveness of the team to fall.

Norming: Hopefully some accommodation is achieved. The team members begin to reach agreement over these various issues. This will be by a process of negotiation, compromise, and finding areas of commonality. As a result of this accommodation, the team begins to develop a sense of identity, and a set of norms or values. These form a basis on which the team members can work together, and effectiveness and motivation begin to increase again towards the plateau. Although norming is important for the ultimate performance of the team, it can have a negative side effect. If the team norm too well they can become very introspective, and isolate themselves from the rest of the organization. They work very well together, but produce something the rest of the organization do not want.

Performing: Once performance reaches the plateau, the team can work together effectively for the duration of the project. The manager has a role of maintaining this plateau of performance. For instance, after the team has been together for too long, the members can begin to become complacent, and their effectiveness fall. If this happens the manager may need to change the structure or composition of the team.

Mourning: As the team reaches the end of its task, one of two things can happen. Either the effectiveness can rise, as the members make one concerted effort to complete the task, or it can fall, as the team members regret the end of the task and the breaking up of the relationships they have formed. The latter will be the case if the future is uncertain. Again, it is the manager's role to ensure that the former rather than the latter happens.

These five stages of team formation may need to be repeated at each stage of the project life cycle if there is a significant change in the composition of the project team. There are several group-working techniques which the manager can use to shorten the forming, storming, and norming stages, such as the application of the start-up processes described in Chap. 12, and in particular the use of start-up workshops.

Having formed the group, the manager's role is to ensure it continues to operate at the plateau of effectiveness. I next describe how the project manager can motivate a team of knowledge workers. But first the manager must be able to determine just how effective the team really is. On a simple level, this can be assessed by the way in which the team achieves its agreed targets, and by the way in which the individuals' and group's aspirations and motivational needs have been satisfied. The team leader and functional managers must ensure both corporate and personal objectives are met. If only the corporate goal is met, then with time there will be an erosion of morale and effectiveness followed by staff attrition. Often, however, it is only possible to measure achievement of these objectives at the end of the project, by when it is too late to take corrective action. Hence, we must also have measures by which to judge the cohesion and strength of a group during the project. Indicators of team effectiveness include

Attendance: Low absenteeism, sickness, accident rates, work interruptions, and labour turnover.

Goal clarity: Individual targets are set, understood, and achieved; the aims of the group are understood; each member of the team has a clear knowledge of the role of the group.

High outputs: Commitment to goal achievement, a search for real solutions, analytical, critical problem-solving using knowledge and skill, the search for widely tested and supported solutions.

Strong group cohesion: Openness and trust among members, sharing of ideas and knowledge, lively and constructive meetings, shared goal.

Motivating the Project Team. How does the manager motivate the members of a team of professional, knowledge workers, to build and maintain their effectiveness and commitment to the project? In the project environment, without the functional hierarchies, distinctions of title, rank, symbols of power and status do not exist, so many factors which are traditionally viewed as providing value to motivate professional staff are not available. In the project environment, managers must find new motivational factors which will be valued by their staff. There are three features of the project environment which have a significant impact on the motivation of personnel:

Matrix organization structures: Within a matrix organization, people do not have the clear indicators of title, status, and rank, as described. They also have reporting lines to two people, a short-term (project) boss, and long-term (functional) boss. Although the project manager tries to motivate the individuals towards the project goals, they often give their primary loyalty to their functional manager. It is that manager who writes their annual appraisal, and has greatest influence over long-term career development. This is exacerbated if annual performance objectives are aligned with the functional hierarchy because projects are of shorter duration than the timescale over which they are set.

Flatter organization structures: With flatter hierarchies being adopted by project organizations, individuals have less opportunity for career advancement, as there are fewer levels to occupy. They spend longer on each level before progressing, which means they have fewer opportunities to measure progress against career milestones, and are less able to judge how their contribution is viewed by the organization. Words of encouragement are not enough, because individuals can only judge their perceived value by progression, which means promotion. With decision-making processes bypassing the centre, individuals may also feel less able to influence their careers, as they no longer have direct contact with senior managers making career decisions. They rely very much on their project managers or their functional managers to act as their salesmen on career matters. This feeling of detachment can be heightened if the individual does not entirely understand the direction or strategy of the company, or how their project contributes to it. Having no direct contact with the centre through their work, they will not have the opportunity regularly to question the reasons for strategic decisions, or to suggest alternatives. This can exacerbate all the previous problems if they perceive their manager as the cause of their isolation.

The transient nature of projects: The transient nature of projects means that an individual's annual performance objectives tend to be aligned with their functional responsibilities rather than their project ones. Similarly, because projects only last a short time, they cannot satisfy an individual's long-term development needs in their own right. They can only be a stepping stone. It is the functional hierarchy which provides the focus for the individual's development, and if the individual is to be committed to projects, they must be assigned to projects which they view as fulfilling their development requirements.

So how do you motivate knowledge workers in this environment to give their commitment to projects? A traditional view of motivation is Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs.10 Maslow proposed that people have five essential needs (higher levels first):

1. Achievement

2. Esteem

3. Belonging

4. Protection

5. Sustenance

People are motivated initially by lower needs. However, as they satisfy one, that reduces in importance, and they become motivated by the next higher. As their needs move up the list the lower ones lose effect. Many of the traditional views on motivation are not valid in the project environment. However, Maslow's hierarchy continues to provide a basis for motivational factors. Many people working on projects have now passed the point at which belonging is the primary need to be satisfied at work; they satisfy that through their leisure activities. They therefore look to satisfy their needs for esteem and achievement. This is especially true of knowledge workers, and leads to five factors for their effective motivation.

Purpose: Knowledge workers must believe in the importance of their work, and that it contributes to the development of the organization. This sense of purpose, and the linking of the work of a project to the mission of the parent organization, can help overcome the uncertainty of the dual reporting structures in a matrix organization.

Proactivity: As career paths become less clear and predictable, and as senior managers become remote, then people want to manage their own career development. Emphasizing the achievement of results, rather than fulfilling roles, and delegating professional integrity through results gives subordinates the opportunity to take responsibility for their own development. Furthermore, allowing people to choose their next project as a reward for good performance on the present one satisfies this need.

Profit sharing: Allowing people to share in the entrepreneurial culture will encourage them to value it. Many organizations now encourage employees to solve their own problems, and to take the initiative to satisfy the customer's requirements, and are allowing employees to share in the rewards. The growing band of freelance workers also shows that many people are taking this initiative into their own hands.

Progression: As people near the top of Maslow's hierarchy, they become conscious of the need for self-fulfillment. They therefore value the opportunity to increase their learning experiences. Each new project is an opportunity to learn new skills, and thereby increase esteem and self-achievement. However, in the flatter organization structures, people may have fewer career milestones to measure their progression. The one yardstick they still have is money (or other status symbols such as company cars). These things remain important, not as motivators in their own right, but as measures of achievement.

Professional recognition: Another measure of achievement is professional recognition. Knowledge workers do not want the anonymity of the bureaucrat, but want to accumulate "brownie points" to contribute to their esteem and achievement. I said above that in the flatter hierarchies of project-based organizations, managers at the centre may not be in direct contact with professional employees. Line managers must therefore ensure that their subordinates do receive due recognition.

Variation of the Motivational Factors with Life Cycle. The efficacy of these five motivators varies throughout the project life cycle (Table 4.4).

Definition: During this stage, the members of the project team try to determine what the project is about, so their focus on its purpose is high. They will try to determine how it can contribute to their development, and so the entrepreneurial spirit will be high. During definition, there will be some opportunity to demonstrate professional skill through problem solving.

Execution: During this stage, the focus switches from the purpose of the project to the work done. The learning opportunities, and chance of profit were set in the definition stage, and there is little chance to influence them during execution. However, through the use of responsibility charts (Sec. 6.4), people can be given responsibility for

TABLE 4.4 Variation of the Motivational Factors Throughout the Project Management Life Cycle

| |||

Factor | Definition | Execution | Close-out |

| |||

Purpose | High | Low | High |

Proactivity | High | Medium | High |

Profit sharing | High | Low | High |

Progression | High | Low | High |

Professional recognition | Medium | Medium | High |

| |||

achieving milestones, and so have some opportunity for demonstrating their professional skill.

Close-out: During close-out, all five factors come back into focus: The purpose becomes important again during commissioning; people deliver their results and receive their due reward, if the project has been profitable people complete their learning experience, and look forward to the next; they receive their professional recognition. During close-out, individuals can be given career counselling to help manage their careers. Individuals should be helped to define their development needs, plan how they are to be achieved, and to develop networks, internal and external to the organization, to be used in their career progression.

Virtual Teams. Virtual teams are very common in a project context.11 The very nature of assembling a unique, novel, and transient teams means we look for the best people to do the work, and they may not always be colocated. Many people talk as if virtual teams are something new, enabled by modern technology. My own view is they have been around for centuries, modern technology just makes them more cost effective and so they are becoming more common. Indeed one definition of a virtual team is that it is a team where the team members are not colocated, and uses modern information and communication technology to communicate with each other. Another definition of a virtual team is any team where there is a boundary within the team that increases the cost of communication across that boundary. The boundary can be distance, time zone, language, culture, or professional differences (marketing versus engineers). We then see that modern information and communication technology is reducing the cost of communication across many boundaries. Virtual teams are assembled because the benefit outweighs the additional cost of communication, but with cheaper communication, we can realize the benefit more often, and hence the greater pervasiveness of virtual teams.

There are four factors that increase the effectiveness of virtual teams. Three we have met already, but they have particular significance for virtual teams. The four are

![]() Communication

Communication

![]() Trust

Trust

![]() Cohesion

Cohesion

![]() Goal clarity

Goal clarity

Through all of the foregoing discussion is the implied importance of the leadership of the project manager. Project managers have to lead in several directions:

![]() Upwards to maintain the support of the sponsor and owner

Upwards to maintain the support of the sponsor and owner

![]() Outwards to win the support of resource providers, professional colleagues, and the range of stakeholders listed in Table 4.2

Outwards to win the support of resource providers, professional colleagues, and the range of stakeholders listed in Table 4.2

![]() Downwards to lead the project team, winning the commitment to the project of people he or she may not have direct line responsibility over

Downwards to lead the project team, winning the commitment to the project of people he or she may not have direct line responsibility over

Over the past century, a number of leadership theories have been proposed, and these have been interpreted into the context of projects. Most recently authors have tried to identify the competencies of leaders,1 and I have been involved in research which attempted to identify the competencies of project managers for different types of project.2

Leadership Theories. One of the earliest leadership theorists was Confiucius, whose ideas formed the basis of the government of China for two and a half millennia.12 He suggested that leaders exhibited four virtues (de):

1. Building relationships (jen)

2. Demonstrating their values (xiao, yi)

3. Following due process (li)

4. Adopting the doctrine of the mean (zhong, rong)

We will see that the first three of these have formed the basis of many leadership theories in the subsequent 2500 years. It is a pity that many managers have lost sight of the fourth, maintaining a balance in what they do—the goldilocks principle, neither too much not too little.

Two hundred years later, Plato and Aristotle were almost the first leadership theorists in Europe. Aristotle suggested a three-faceted approach to leadership, in Greek pathos, ethos, logos, or building relationships, demonstrating values, and following due process, (sound familiar, but what happened to the Goldilocks principle). I said earlier in the chapter that many western managers leap in with the logic. What differentiates a leader from a manager is the leader starts by building relationships and selling the vision, and once he or she has achieved that, then and only then says, "And this is how we have to do it."

Throughout the twentieth century, six schools of leadership developed:

The Trait School. It came to prominence in the 1930s to 1940s, and suggests that leaders exhibit certain traits they are born with. Leaders are born, not made. Kirkpatrick and Lock13 suggested that effective leaders exhibit the following traits:

![]() Drive and ambition

Drive and ambition

![]() The desire to lead and influence others

The desire to lead and influence others

![]() Honesty and integrity

Honesty and integrity

![]() Self-confidence

Self-confidence

![]() Intelligence

Intelligence

![]() Technical knowledge

Technical knowledge

The Behavioural School. It was popular in the 1940s and 1950s, and assumes effective leaders display certain behaviours or styles, which can be developed. Most theories from this school characterize leaders by how much they exhibit styles based on one or more of the following parameters:

![]() Concern for people or relationships (jen, pathos)

Concern for people or relationships (jen, pathos)

![]() Concern for production or process (li, logos)

Concern for production or process (li, logos)

![]() Use of authority

Use of authority

![]() Involvement of the team in decision-making (formulating decisions)

Involvement of the team in decision-making (formulating decisions)

![]() Involvement of the team in decision-taking (choosing options)

Involvement of the team in decision-taking (choosing options)

![]() Flexibility versus the application of rules

Flexibility versus the application of rules

Blake and Mouton's14 is one of the best-known theories. They developed a two-dimensional grid based on concern for people and concern for production, each graded on a scale of 1 to 9 and identified five leadership styles, appropriate in different circumstances:

![]() Impoverished (1,1)

Impoverished (1,1)

![]() Authority obedience (1,9)

Authority obedience (1,9)

![]() Compromise (5,5)

Compromise (5,5)

![]() Team leader (9,9)

Team leader (9,9)

Most authors from the behavioural school assume different behaviours or styles are appropriate in different circumstances, but that was formalized by the contingency school.

The Contingency School. This school from the 1960s and 1970s developed the idea that different styles are appropriate in different circumstances. They suggest you should

1. Assess the characteristics of the leader.

2. Evaluate the situation in terms of key contingency variables.

3. Seek a match between the leader and the situation.

One contingency theory that has proved popular is path-goal theory.15 The idea is the leader must help the team find the path to their goals and help them in that process. Path-goal theory identifies four leadership styles: directive, supportive, participative, and achievement-oriented.

The Visionary School. It followed in the 1980s and 1990s, and identified two types of leaders: those who focus on relationships and communicate their values, and those who focus on process, called transformational and transactional leaders, respectively.16

1. Transactional leadership

![]() Emphasizes contingent rewards, rewarding followers for meeting performance targets

Emphasizes contingent rewards, rewarding followers for meeting performance targets

![]() Manages by exception, taking action when tasks are not going to plan

Manages by exception, taking action when tasks are not going to plan

2. Transformational leadership

![]() Exhibits charisma, developing a vision, engendering pride, respect, and trust

Exhibits charisma, developing a vision, engendering pride, respect, and trust

![]() Provides inspiration, motivating by creating high expectations, and modelling appropriate behaviours

Provides inspiration, motivating by creating high expectations, and modelling appropriate behaviours

![]() Gives consideration to the individual, paying personal attention to followers, and giving them respect and personality

Gives consideration to the individual, paying personal attention to followers, and giving them respect and personality

![]() Provides intellectual stimulation, challenging followers with new ideas and approaches

Provides intellectual stimulation, challenging followers with new ideas and approaches

Each is appropriate in different circumstances. Following the work of Vic Dulewicz and Malcolm Higgs,1 we can predict that transformational leadership will be required in more complex change, but in fact transactional leadership will work better with simpler change, where following due process is all that is required, and too much vision will be distracting.

The Emotional Intelligence School. It has developed through the 1990s and early part of this decade. It assumes all managers have a reasonable level of intelligence, and therefore what differentiates leaders is not their intelligence, but their emotional response to situations.17 The school identifies 19 leadership competencies grouped into four dimensions:

1. Personal competencies

![]() Self-awareness (mainly Confucius's moderation)

Self-awareness (mainly Confucius's moderation)

![]() Self management (mainly Confucius's values)

Self management (mainly Confucius's values)

2. Social competencies

![]() Social awareness (mainly Confucius's values)

Social awareness (mainly Confucius's values)

![]() Relationship management (mainly Confucius's relationships)

Relationship management (mainly Confucius's relationships)

TABLE 4.5 Fifteen Leadership Competencies

| ||||

Group | Competency | Goal | Involving | Engaging |

| ||||

Intellectual (IQ) | Critical analysis & judgement | High | Medium | Medium |

| Vision and imagination | High | High | Medium |

| Strategic perspective | High | Medium | Medium |

Managerial (MQ) | Engaging communication | Medium | Medium | High |

| Managing resources | High | Medium | Low |

| Empowering | Low | Medium | High |

| Developing | Medium | Medium | High |

| Achieving | High | Medium | Medium |

Emotional (EQ) | Self-awareness | Medium | High | High |

| Emotional resilience | High | High | High |

| Motivation | High | High | High |

| Sensitivity | Medium | Medium | High |

| Influence | Medium | High | High |

| Intuitiveness | Medium | Medium | High |

| Conscientiousness | High | High | High |

| ||||

The idea is the leader needs to develop self-awareness first. Having developed that, he or she can then develop self-management and social awareness, and from those two develop relationship management. David Goleman and his coauthors identify six management styles, exhibiting different profiles of the competencies: visionary, coaching, affiliative, democratic, pacesetting, and commanding. Through a survey of 2000 managers, they identified situations in which these different styles are appropriate. The first four are best in certain situations, but all four are adequate in most situations medium to long term. They classify the last two styles as toxic. They say they work well in turn-around or recovery situations, but if applied medium to long term they can poison a situation, and demotivate subordinates.

The Competence School. This is the most recent school. Its says effective leaders exhibit certain competencies. It encompasses all the other schools because traits and behaviours are competencies, certain competency profiles are appropriate in different situations, and it can define competency profile of transformational and transactional leaders. After a review of the literature on leadership competencies, Vic Dulewicz and Malcolm Higgs1 identified 15 which influence leadership performance (Table 4.5). They group the competencies into three types, intellectual (IQ), managerial (MQ), and emotional (EQ). They also identified three leadership styles, which they called goal oriented, involving, and engaging (Table 4.5). Through a study of 400 managers working on organizational change projects they showed goal-oriented leaders are best on low-complexity projects, involving leaders best on medium-complexity projects, and engaging leaders best on high-complexity projects.

The Six Schools and Project Management. These schools have been reflected in writings about the leadership skills of project managers:

The Trait School. Through work I did at Henley Management College, I identified seven traits of effective project leaders.

Problem solving. The purpose of every project is to solve a problem for the parent organization, or to exploit an opportunity (which also requires a problem to be solved). But also projects entailed risk, and so during every project you are highly likely to encounter problems. Project managers must be able to solve them.

Results orientation. Projects are about delivering beneficial change. But also, if you plan in terms of the results your plan is much more robust and stable than if you plan in terms of the work (Sec. 3.5). Thus project managers need to be focused on the results of their project.

Self-confidence. This is part of the emotional intelligence of project managers. They must believe in themselves and their ability to deliver.

Perspective. Project managers must keep their projects in perspective. A project manager must be like an eagle. They must be able to hover on high and see their project within the context of the parent organization. But they must have eagle-eyed sight to be able to see a small mouse on the ground, and to be able to sweep down and deal with it, but then also be able to rise again to hover above the project.

Communication. The project manager must be able to talk to everybody from the managing director down to the janitor. Sometimes the janitor knows more about project progress than anybody else. The janitor talks to everybody (see Example 4.9).

Negotiating ability. Project planning is a constant process of negotiation. As a project manager you ask people to work for you. You must convince them that it is worthwhile and beneficial to themselves to do that.

Energy and initiative. When the project gets into trouble, the project manager must be able to lift everybody else onto their back and lift them out of the hole.

Example 4.9 Talking to the janitor

When I was a post-doctoral research fellow, I had an office in one of a pair of houses. We had offices in one house while the other was being renovated. The plan was when the other was complete we would move into that house, while the one we were currently occupying was renovated. I was due to be away for a month to attend a conference. About a week before I was due to leave, the janitor, a retired miner called Frank, asked me when I was going to be away. From the 20th August to the 20th September, I said. Frank said that we were due to move into the other house on the 14th September, so it might be worthwhile for me to put my books in a tea-chest before I left. I said that was a good idea, but decided to check it out first with the administrator of the engineering department. I spoke to his secretary, but she denied any knowledge of the move. So I next asked the builders, but they said they would not be finished until late October or early November. I locked my office door, and went off to the conference. When I came back, I found that the door had been forced, and that the move had taken place on 14th September, the very day Frank had predicted. Of course, he had spoken to the University Estates people as they came to survey the work.

The Behaviour and Contingency Schools. David Frame identified four leadership styles of project managers, and showed different styles are appropriate at different stages of the life cycle.18 I describe this more fully in Sec. 6.4.

The Visionary School. Anne Keegan and Deanne den Hartog19 assumed that project managers need to have a transformational leadership style, and set out to show that to be the case. In the event they found a slight preference for transformational leadership, but not a strong preference. I think the reason for this is that complex projects need a transformational style, but less complex projects need a more conscientious, structured, transactional style, as suggested by Vic Dulewicz and Malcolm Higgs.1 Too much strategic perspective can be a distraction on simpler projects. This has been borne out by the work I will describe below.

The Emotional Intelligence School. There is very little work setting project leadership within the context of the emotional intelligence school. However a contribution was made by Liz Lee-Kelly and K Leong almost by chance.20 They were researching how the project manager's competence at managing five functions of management described in the next part contributed to project success. What they found was that there is a significant relationship between the leader's perception of project success and his or her personality and contingent experiences. Thus the inner confidence and self-belief from personal knowledge and experience are likely to play an important role in a manager's ability to deliver a project successfully. The project manager's inner self-confidence has a significant impact on their competence as a project leaders and hence on project success.

The Competence School. Ralf Müller and I investigated which of the competencies in Table 4.5 are correlated with project success.2 We looked at different types of projects to see if different leadership styles are appropriate on different types of project. We found that emotional intelligence made a significant contribution to project success on almost all types of projects. The exceptions were mandatory projects and fixed price contracts where managerial competence was more significant. Thus, on most projects self-awareness and building relationships are more important than following due process. But I think we can understand why following due process may be more important on mandatory projects and fixed price contracts. On time and material contracts intellect was also important. We also looked at how the 15 individual competencies related to success. We found that some were positively correlated and some negatively. Some of our results are shown in Table 4.6.

You will see that communication gets mentioned the most, being important on all types of project except engineering and high complexity projects. On engineering projects, methodical working is important. On information systems projects it is self-awareness, and on organizational change motivation. It is interesting that information

TABLE 4.6 Leadership Competencies Contributing to Project Success

| |||

Project attribute | Project type | Important | Unimportant |

| |||

| All projects | Conscientiousness | Strategic perspective |

|

| Sensitivity |

|

|

| Communication |

|

Application area | Engineering | Motivation | Vision |

|

| Conscientiousness |

|

|

| Sensitivity |

|

| Information systems | Self-awareness | Vision |

|

| Communication |

|

| Organizational change | Motivation | Vision |

|

| Communication |

|

Strategic importance | Mandatory | Developing |

|

| Renewal | Self-awareness |

|

|

| Communication |

|

| Repositioning | Motivation |

|

|

| Communication |

|

Complexity | Medium | Emotional resilience | Vision |

|

| Communication |

|

| High | Sensitivity |

|

Contract type | Fixed price | Sensitivity |

|

|

| Communication |

|

| Time and materials | Self-awareness | Empowering |

|

| Communication |

|

| |||

systems projects show the same profile as renewal projects and organizational change projects as repositioning. What is controversial is that vision appears as unimportant so often, and may be inconsistent with what I have said earlier in this chapter. What I would say is that having a clear picture of the end state of the project, and setting clear goals is important. Goal clarity was identified as important for project team performance. What is meant by vision here is being able to picture many possible end points for the project, and in fact on most projects that is a distraction, and will reduce goal clarity. So it is important to have a vision of the one clear goal of the project, but don't get distracted by lots of alternatives. The message seems to be that small, simple engineering projects need managing, whereas larger, more complex information systems and organizational change projects need leading.

Ralf Müller and I do not expect that organizations would conduct a psychometric test on potential project managers at the start of every project. But we do suggest that they conduct a psychometric test at least once as part of the annual review process on project managers in the pool of project managers. They can then identify what shortfalls individual project managers have in their profile and work on developing appropriate competencies through the project management development program. If somebody's profile is totally inappropriate for the type of project they have to manage they can be dropped from the pool of project managers, but we did find that the career tends to be self-selecting and people don't stay working as project managers if their profile does not fit. Individuals can also look to enhance their competencies for the types of project they want to work on.

The two clear messages are emotional intelligence is important to being a project manager, and communication is important on all projects, which is where we started this chapter.

1. People react to change differently, depending on the level of change within the organization.

2. You cannot expect people to immediately accept and internalize your proposals for change within the organization. You must lead them through carefully, getting them to appreciate the benefit of the proposed change, to see that it is sensible, and will not unduly affect their position within the organization, before getting them to fully accept it.

3. Recognize that extreme change can lead to significant emotional responses which must be managed carefully.

4. There is a seven-step process for stakeholder management:

![]() Identify interested parties.

Identify interested parties.

![]() Identify possible success criteria.

Identify possible success criteria.

![]() Identify stakeholders and their interests.

Identify stakeholders and their interests.

![]() Develop a stakeholder persuasion strategy.

Develop a stakeholder persuasion strategy.

![]() Monitor their response.

Monitor their response.

![]() Monitor the impact of the environment.

Monitor the impact of the environment.

![]() Make changes to the strategy if necessary.

Make changes to the strategy if necessary.

5. To analyze stakeholders you need to answer three questions.

![]() Are they for or against the project?

Are they for or against the project?

![]() Can they influence the outcome?

Can they influence the outcome?

![]() Are they knowledgeable or ignorant about the project?

Are they knowledgeable or ignorant about the project?

6. The stakeholder management strategy will depend on the answers to these questions.

7. When developing a communication plan for a project, answer the following questions:

![]() What are the objectives of each communication?

What are the objectives of each communication?

![]() Who are the target audience?

Who are the target audience?

![]() What are the key messages?

What are the key messages?

![]() What information will be communicated by whom?

What information will be communicated by whom?

![]() When will the information be given?

When will the information be given?

![]() What mechanisms will be used?

What mechanisms will be used?

![]() How will feedback be encouraged?

How will feedback be encouraged?

![]() What will be done with the feedback?

What will be done with the feedback?

8. Project teams are unique, novel, and transient, like projects. There are five steps to team formation and maintenance:

![]() Form

Form

![]() Storm

Storm

![]() Norm

Norm

![]() Perform

Perform

![]() Mourn

Mourn

9. Measures of team performance are

![]() Attendance

Attendance

![]() Goal clarity

Goal clarity

![]() Outputs

Outputs

![]() Cohesion

Cohesion