CHAPTER 17

DEVELOPING

ORGANIZATIONAL CAPABILITY

In Chap. 16, we looked at program and portfolio management, a key component of governance of the organizational context, linking the objectives of projects to the strategic objectives of the organization, and defining which projects will be done to achieve those objectives. In this chapter, we look at another key component, developing organizational project management capability, which helps define the means by which the organization achieves its project objectives, and hence its strategic objectives. First I consider what we mean by organizational project management capability. Then I discuss the development of individual competence, a key component of organizational capability. But the organization can have capability over and above the competence of the individuals; the whole is much greater than the sum of the parts. So I consider four practices and four processes for developing capability, and four areas for managing the knowledge which underpins that capability. Finally, there are things that can stop an organization from improving its capability. These are known as competency traps, Sec. 17.6.

Organizational project management capability comprises three components:

The Project Management Body of Knowledge

First, the organization needs to know what components of project management are relevant to the delivery of its projects, and how it will operationalize each one. It can seek guidance from a number of sources, the Project Management Institute (PMI) PMBoK,1 the IPMA ICB,2 or the Association for Project Management (APM) BoK.3 Or else, you can adopt the components of project-based management as outlined in Parts 1, 2, and 3 of this book. The organization's definition of its body of knowledge will include the following:

Project Life Cycle. The organization needs to understand the life cycle appropriate for its type of projects, as outlined in Chaps. 1 and 11. There may be different life cycles appropriate for different types and sizes of project.

Management Cycle. The organization also needs to understand how it will operationalize the management cycle. It may adopt the very simple cycle suggested in Chaps. 1 and 11:

![]() Plan the work.

Plan the work.

![]() Organize the resources.

Organize the resources.

![]() Implement by assigning work to resources.

Implement by assigning work to resources.

![]() Control progress.

Control progress.

Or it may adopt a more extensive cycle as suggested by PMI comprising:

![]() Starting processes

Starting processes

![]() Planning processes

Planning processes

![]() Organizing processes

Organizing processes

![]() Controlling processes

Controlling processes

![]() Closing processes

Closing processes

The organization also needs to understand the difference between the management cycle and the project life cycle, and whether the difference matters for its size of projects. For instance, if the organization is involved in programs of small projects, it will apply the life cycle at the program level and the management cycle at the project level. If on the other hand it is involved in large projects, it will apply the life cycle to projects and the management cycle at each stage of the project as illustrated in Fig. 1.8.

The Functions of Project Management. The third component of the body of knowledge is the functions of management. In Part 2, I suggested six functions, managing scope, organization, quality, cost, time, and risk. I also suggested stakeholder management in Chap. 4. PMI suggests nine functions:

![]() Five of my six from Part 2.

Five of my six from Part 2.

![]() What it calls managing integration rather than organization.

What it calls managing integration rather than organization.

![]() What it calls managing communication, covered under stakeholder management (Chap. 4) and communication between the sponsor and manager (Chap. 15).

What it calls managing communication, covered under stakeholder management (Chap. 4) and communication between the sponsor and manager (Chap. 15).

![]() Managing human resources and procurement—I do not suggest that last two are unimportant, I have just made them beyond the scope of this book, each deserving a book in their own right.4, 5

Managing human resources and procurement—I do not suggest that last two are unimportant, I have just made them beyond the scope of this book, each deserving a book in their own right.4, 5

Project Management Methodology

Not only does the organization need to know how it is going to operationalize the individual components of the body of knowledge, it needs to put all of those together into an integrated project management methodology to deliver individual projects from concept to realizing benefit from the strategic change introduced (operation of the new asset). None of the professional associations' bodies of knowledge1, 2, 3 actually recommends a methodology, though APM's3 comes the closest. (I was part of the committee that developed the initial draft and we were told by APM to take it out.) The PRINCE26 process is a methodology but I would offer the methodology recommended in this book as illustrated by Fig. 1.11.

Technical and Craft Skills

This last component of organizational capability does tend to be underemphasized by the project management community. Yes, project management is a generic skill, and so the techniques can be applied to all types of project. But the techniques do need to be packaged in different ways depending on the type of project7, 8 and the organization does need to be expert in the basic technical and craft skills that are used in the projects it undertakes. If it has the necessary technical and craft skills, it will know how to tailor its project management methodology and the project management functions to its type of projects.

17.2 DEVELOPING INDIVIDUAL COMPETENCE

A necessary component of organizational capability is the competence of individuals. Without competent individuals the organization can have no capability. In this section, I consider how we define the competence of individuals, the components of competence, how it varies at different stages of an individual's career, and how to assess and develop it.

Defining Competence

There are two main ways of defining the competence of individuals.

Competency Model or Attribute Approach. The competency model or attribute-based approach, popular in the United States,9, 10 defines competence as the knowledge, skills, and personal characteristics required to deliver superior performance. A competency is an individual component of competence. There are surface competencies, knowledge, and skills, which can be easily measured and developed, and core competencies which are less easily measured. Inherent in this approach is the idea of threshold and differentiating competencies. Threshold competencies are the basic ones essential for doing the job, and differentiating ones are those leading to superior performance. The bodies of knowledge produced by the professional associations1, 2, 3 define the threshold knowledge and skills required to manage projects. They therefore conform to this approach, but define the basic competencies rather than the differentiating ones.

Competency Standards or Performance-Based Approach. The other approach, rather than trying to measure the inputs to competence, tries to measure the outputs, and has been popular in United Kingdom and its former dominions (Australia and South Africa). Competence can be measured by performance in accordance with defined occupational, professional, or organizational standards.11 Several performance-based standards for project management have been produced around the world.12,13,14,15

Combined Approach. Lynn Crawford15 has developed a combined approach to defining competence. She suggests there are three components to competence:

Input competencies: The required knowledge and skills to do the job. Of these, knowledge tends to be a threshold competence, whereas skill tends to be a differentiating competencies.

Core competencies: The personal characteristics including motives, traits, and self-concept that improve performance. These are differentiating competencies.

Output competencies: The ability to perform required activities as defined by professional, occupational, or organizational standards.

Many years ago, I was introduced to a competency model by an Information Technology (IT) vendor. They defined three levels of competency, described by the words, I know, I can do, and I adapt and apply.

I know: This is the knowledge required to do the job.

I can do: This is the ability to apply the knowledge to perform routine tasks (skill).

I adapt and apply: This is the ability to apply your skill in unfamiliar situations to develop new methodologies to deal with those unfamiliar situations.

According to this model, an individual does not perform until they could adapt and apply. Further, it was not that a certain level of knowledge gave you an equivalent level of ability to do and that gave you an equivalent level of ability to adapt and apply. You needed quite a bit of knowledge before you could do, and substantially more knowledge giving additional ability to do before your could adapt and apply. But you would reach a threshold level of knowledge where more knowledge would not increase you ability to adapt and apply any more. Only other things, including experience, would do that.

They likened it to learning a language. You need a certain amount of vocabulary and grammar before you can compose simple sentences, but you need to be able to compose substantially more sentences before you can hold a conversation. I have a 2000-word vocabulary in French but have difficulty conducting conversations because I lack experience and self-confidence.

Explicit versus Tacit Knowledge. A related concept is that of explicit versus implicit or tacit knowledge.16 Explicit knowledge is knowledge that can be codified and written down. It is mainly what we learn when we go on a training course or read a book. Implicit or tacit knowledge is inherent knowledge that we gain mainly through practice and experience. We know how to do things without thinking about them. You mainly drive a motor car using tacit knowledge; you can't think through the process of doing an emergency stop when one is called for. Similarly with a language, you start off holding a conversation using explicit knowledge, but it tends to be slow as you have to translate what you have heard and what you are going to say before replying. But with experience you conduct the conversation in the language and the language has meaning without translating.

In the models above, knowledge mainly means explicit knowledge, and tacit knowledge mainly falls under skills. Kolb17 introduced a learning cycle for individuals (Table. 17.1) showing them cycling between gaining tacit knowledge through experience and explicit knowledge through training and education. The two reinforce and support each other. Explicit knowledge gives you structures that explains why things work in the way you expect and having those structures makes you better able to test out concepts through your work experience and improve your tacit knowledge further, and develop your own new explicit knowledge, enabling you to adapt and apply.

Threshold Competence. I wish to explore a little bit further the concept of threshold competence. Lynn Crawford showed in her own research that project management competence as measured by the professional associations in their certification programs tends to be threshold competence.15 A pass grade on the certification programs is necessary to be able

TABLE 17.1 Kolb's Learning Cycle for Individuals

| To | ||

| Tacit knowledge | Explicit knowledge | |

| |||

From | Tacit | Concrete Experience Creating tacit knowledge through on-the-job experience | Observation and reflection Understanding how and why things work |

Explicit | Testing of concepts Testing explicit knowledge in practice to see if it works | Abstract concepts and generalizations Codifying knowledge through education and training | |

| |||

to work effectively as a project manager, but a higher score does not make you a better project manager. It is other things that make you a better project manager (in your current job role), including years of experience.

I should qualify this. In the last chapter I said there was a substantial difference between the management of a $50,000 project and a $50 million project. The former tends to require primarily technical skills (as measured by the certification programs, especially PMI's), whereas the latter requires substantially more people and strategic management skills. Thus more knowledge won't make you better in your current role, but different knowledge is needed for different more advanced job roles.

Levels and Stages of Development

This leads to the concept of T-shaped managers (Fig. 17.1) illustrating different levels of management and different competence profiles required. The height of the upright shows the depth of professional involvement (primarily technical competence) and the width of the upright shows the breadth of that. The width of the cross-bar illustrates the range of professional contacts and the depth shows the amount of managerial competence required (mainly people management and strategic).

Team leader: A person's project management career starts as a team leader, managing a single discipline team, perhaps a $50,000 component of a larger project. Perhaps the team is just mechanical designers, and the team leader has to interface with other teams from the project, consisting of civil, electrical, and other engineers; or it is programmers, interfacing with testers and systems analysts. The team leader needs basic project management and people management skills. Their technical skills will probably be domain specific; that is, their own area of professional expertise will be the same as the team.

Junior project manager: The person will now be managing a small ($5 million) project, perhaps part of a larger program. There will be several teams on the project, several types of engineers, or teams of programmers, analysts, and testers. The manager is less involved professionally but has a wider range of skills to manage. The range of contacts has widened to other project managers in the program or portfolio, and line managers of the project team members. The manager now needs more people management skills, some other functional skills such as accounting to be responsible for project cost, and also needs to understand the project and program's contribution to corporate strategy. The manager's professional background is probably still domain specific: if it is an

FIGURE 17.1 T-shaped managers.

engineering project they will be an engineer, and if it is an ICT project they will be from an ICT background. So, although there will be people on the project team from other professions they will be related professions.

Project or program manager: The person is now managing a larger, more complex project or program ($50 million) consisting of several unrelated professions, engineers, ICT people, sales and marketing personnel. Their background can no longer be domain specific, though it may be from the dominant profession. Their contacts go outside their parent organization to clients and suppliers. They need more strategic management and commercial skills.

Project or program director:The person is now managing the largest of projects or programs. Their contacts may now go outside the industry and international. They need directorial and governance skills.

Assessing Competence

Competence will be assessed against some measure of the desired competence for the job being performed. This will probably be a competence model for the job, and may specify the desired input competence (knowledge, skills, and experience), or the desired output competence (performance), or both. It may be based on one of the competence frameworks mentioned above: input competence for the bodies of knowledge of the professional associations1, 2, 3 or output competence form one of the performance standards.12, 13, 14 The competence model may be part of a job description.

At the individual's regular appraisal (once or twice a year usually), their current competence will be assessed against the model. Their competence will be assessed against the desired standards for the job they are currently doing to determine any shortfalls but may also be assessed against the standards for the next promotion or development they are looking for. In this way, the gap between their current and desired level of competence will be determined. This indicates the desired training or experience the individual requires to achieve the necessary development either to meet the requirements of his or her present job or progress to his or her next development.

Martina Huemann, Anne Keegan, and I suggested that this assessment should be conducted by the individual's line manager and not his or her project manager, because the timescale over which relevant decisions are taken is over several years, much longer than the project he or she may be currently working on.18 However, the assessment should be based on appraisals conducted by the project manager. If the in-line appraisal is divorced from performance on the project then it is bad for the individual's motivation and for the cohesion of the project team he or she is currently working on. Some organizations have formalized in-project appraisals. One software consultancy we interviewed conducts an in-project appraisal at the end of every project, and once every three months if projects last longer, so the in-line appraisal, held once every six months, is based on at least two project appraisals.

Developing Competence

Competence needs to be developed over the short, medium, and long term.

Long Term. In the long term, the firm needs to plan how to fill its forecast competence requirements several years hence, developing project managers and other project professionals to work on the projects it expects to be doing. Anne Keegan and I found the engineering construction industry tends to take a very long-term view, taking 15 years to develop project managers capable of managing projects of $500 million or greater.19 They try to identify people aged 25 who they can develop to manage projects of $500 million plus at the age of 40. We asked one interviewee how they identify potential candidates aged 25. He said, "People who are vocal with their ambition." In that industry they tend to adopt what Anne and I labelled the spiral staircase career. People are given a range of experiences throughout their career, moving between different types of job role. In the early stages of their career, the first two levels described above, they will tend to move between technical design and project roles. For the remainder of their career they may occupy technical roles, project roles, line management roles, and customer interfacing roles. There are at least two advantages of this:

![]() It develops more rounded individuals.

It develops more rounded individuals.

![]() It avoids the Peter principle.

It avoids the Peter principle.

The Peter principle occurs in functional, hierarchical line management, where people are promoted up the hierarchy. It states that people keep on being promoted until they reach a level at which they are incompetent, and there they stay for the rest of their careers—it is impossible to demote them back to the level where they were last competent. The result is organizations become staffed with incompetent people. In the project-based organization, with the spiral staircase career, people are promoted half or even quarter steps into different job roles. If they are uncomfortable in their new role, they can be moved sideways into one where they were last comfortable without any loss of face, and then progress up that ladder (see Example 17.1).

In the ICT industry, projects tend to be smaller and so people are developed for project management roles more quickly but they move from there to program management roles. The ICT industry tends to use pairing, where two people do a job which strictly one would do. By doing that it creates more innovative solutions and also develops twice as many people able to do the job.

One company that Martina Huemann, Anne Keegan, and I interviewed had what it calls development cells.18 These are people responsible for identifying the future needs of the company and talent scouting for potential candidates who can be developed to fulfil them. By this method, they also avoid line managers Bogarting talent, holding on to good people both to the detriment of their career development, and the detriment of the firm and its needs for developing good people.

These long-term decisions need to be taken by line managers because the time horizon is very much longer than projects.

Example 17.1 Moving to a more suited position

One of the people Anne Keegan and I interviewed had been director of projects in his company on the company board and was moved to be project director on a $1.5 billion project for a major client that wanted the job done one-third faster than the previous record. This was a very high-risk project, and it was felt he had the skills to deliver it (which he did successfully). He was given a wage increase to go from being board director to project director because it was felt that this carried higher risk. But he was taken from a job where he was not comfortable (board director) to one where he was a perfect fit and could make a significant contribution to the company without any loss of face.

Medium Term. Medium-term development has a time horizon of one or two years, aiming to develop people to fill the gaps in their competence profile to make them more competent in their current job role, or to develop them for their next promotion. This will be in the form of training or perhaps education programs leading to master degrees. It will also be in the form of on-the-job experience to develop appropriate skills and tacit knowledge. The big issue is when at the routine appraisal in the line it is identified the individual needs to work on a certain type of project to get the developmental experience they need, and then shortly afterwards such an opportunity arises but their current project is only part way through. Do you move them to gain the experience or insist that they complete their current project, by which time the opportunity will have passed? Enlightened organizations move people for several reasons:

![]() It is beneficial to the organization to develop appropriate staff for future needs.

It is beneficial to the organization to develop appropriate staff for future needs.

![]() It is beneficial to the individual.

It is beneficial to the individual.

![]() If you don't show commitment to people's development they may leave anyway.

If you don't show commitment to people's development they may leave anyway.

![]() The current project is a development opportunity for somebody else.

The current project is a development opportunity for somebody else.

These decisions must also be taken in the line because the time horizons are still longer than the duration of projects, but project managers need to be involved because they have to support the decisions.

Short Term. Individuals may also need to develop specific competencies to work on their current project. Project managers will now be very much more involved and may have to pay for the requisite training out of the project budget. Martina Huemann, Anne Keegan, and I came across two interesting examples of on-the-project training:

1. The first was a research and development organization, which would develop new technology early in the project and then test it under extreme conditions later in the project. They only had one opportunity to get the test right. So the project team members who had to do the testing went through expensive training in the use of the new technology and how to test it, and did several dummy runs under simulated conditions, so they could get it right when they had their one chance to do it.

2. The second was a software consultant that had to build up a project team from 32 to 96 people to do a development job for a client. The people joining the team had to be introduced to the legacy software and systems and strategy for the new system. Each person needed one week's training and only eight people could be trained at a time. So the training determined the rate at which people could join the team and it took eight weeks much to the annoyance of the customer.

17.3 DEVELOPING ORGANIZATIONAL CAPABILITY

The competence of individuals is a necessary component of organizational capability but not a sufficient component. Organizational capability is much more than the sum of the parts. Over the next two sections, I consider how to develop organizational capability describing four practices and four processes for developing it. There are four practices that can help organizations to develop organizational capability.

Procedures Manuals

A set of procedures manuals embodies the organization's project management capability. It sets out how the organization does the things I described in Sec. 17.1: the project life cycle, the management cycle, and the project management functions. Once captured, the procedures manual is the document that can be used to train and develop apprentice project managers.

Purpose of the Procedures Manual. There are several reasons why organizations need procedures manuals. They can provide

![]() A guide to the management processes

A guide to the management processes

![]() A consistent approach and common vocabulary (see Example 17.2)

A consistent approach and common vocabulary (see Example 17.2)

![]() A basis for company resource planning

A basis for company resource planning

![]() Training of new staff, especially apprentice project managers

Training of new staff, especially apprentice project managers

![]() Demonstration of procedures to clients, perhaps as part of contractual conditions

Demonstration of procedures to clients, perhaps as part of contractual conditions

![]() The basis for quality accreditation

The basis for quality accreditation

Example 17.2 A common vocabulary

I worked in a company where the word "commissioning" was taken by the mechanical engineers to mean M&E trials, by the process engineers as the period following M&E trials during which the process was proved, by the plant operators as the period following process testing in which the first product was produced, and by the software engineers as all of those combined in which the computer control system is tested and proved.

A colleague reports working on a project to construct a petrochemical facility for which there were two project managers, one responsible for design, and one for construction. When asked what they understood by completion, one said completion of M&E trials, the other operating at 60 percent of design capacity. Both were working to the same day, even though the two dates are at least three months apart.

He reports another project to develop a computer system where when asked the same question people gave answers ranging from completion of beta test to the system has operated for 12 months without problem. Again they were working to the same date even though they were again at least 15 months apart.

On these projects, some people were going to judge them a success, and some a disaster.

However, some words of warning about the procedures manual:

Guidelines not rigid rules: I emphasized right back in Chap. 1 that the procedures should be guidelines not rigid rules. Every project is different and so the procedures need to be adapted to the needs of every project. The procedures represent organizational best practices, but the needs of the project and customer need to be accounted for (see Example 17.3). But I have said before, the more you change the procedures the more likely you are to make a mistake, so you want to use the standard as much as possible.

Different procedures for different types of project: It is also necessary to have different procedures for different types of project.20 You need different procedures for different sizes of projects and for different technologies. Lynn Crawford, Brian Hobbs, and I gave guidance on how to categorize projects to choose appropriate procedures.21

Example 17.3 Adapting the procedures

I worked with a major design and construction contractor from the engineering industry. They would not let project managers manage projects until they knew how to adapt the procedures to the needs of the project; it was part of their tacit knowledge. Apprentice project managers were given the procedures and told to follow them to the letter as they shadowed their mentor, but they would not be let loose on their own until they knew how to adapt them.

Structure of the Procedures Manual. I suggest that the procedures manual should have the following parts:

Part 1—Introduction: This explains the structure and purpose of the procedures manual.

Part 2—Project strategy: This describes the approach to project management to be adopted by the organization, and the basic philosophy on which it is based. It will cover issues such as those described in Chap. 3 and Sec. 17.1. It describes the project model, introduces the stages of the life cycle to be followed (Part 3), and explains why they are adopted. It also explains the need to manage project management functions, and also the need to manage risk.

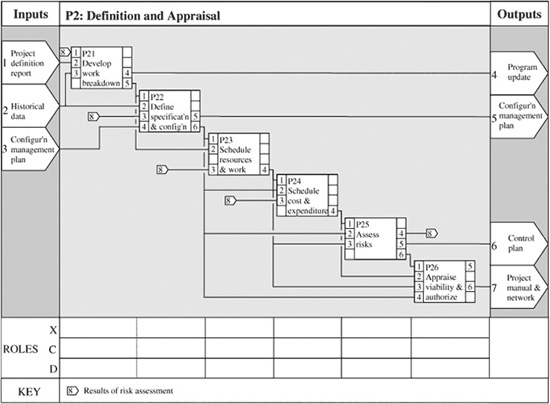

Part 3—Management processes: This describes the procedures to be followed at each stage of the life cycle. The inputs, outputs, and their components are listed, and the management processes required to convert the former to the latter are listed sequentially. Table. 17.2 presents the contents page of a manual for an IT project, which shows that in some areas the breakdown was taken to between one and three levels below the project stage. It is adapted from manuals I have prepared for clients. In the procedures manuals of Table. 17.2, I drew pictorial representations of the processes to achieve each stage or substage in the life cycle. Figures 17.2 and 17.3 are those for successive levels of breakdown. Where there is a lower level of definition, the process is shown as a fine box. Where the process is the lowest level, it is shown as a bold box. Against each bold box were listed the inputs, outputs, and steps required to achieve it.

Part 4—Supporting procedures: This part explains supporting procedures used throughout the project. It may describe the method of managing the project management functions in Part 2, scope, organization, quality, cost, time, and risk, or it may explain some administrative procedures, such as program and portfolio management, configuration management, or conducting audits and health checks (Sec. 18.3), or methods of data collection (including time sheets), or the role of the project support office. Only those important in the particular environment will be necessary.

Appendices—These may contain blank forms and samples.

Project Management Community of Practice

A project management community of practice provides a forum through which project managers can meet, exchange ideas, and form self-supporting networks. A community of practice can provide many benefits including:

![]() The support and mentoring of apprentice project managers

The support and mentoring of apprentice project managers

![]() A network through which project managers can meet and learn what other project managers are doing

A network through which project managers can meet and learn what other project managers are doing

![]() A development cell to identify good project managers worth developing further, for the benefit of the organization and their careers

A development cell to identify good project managers worth developing further, for the benefit of the organization and their careers

I have worked with many organizations, including consultancies, software suppliers, and the military, who create communities of practice. A common feature is a regular meeting, usually about once every three months, in the form of a conference or seminar, where project managers can meet. A typical pattern is a seminar, lasting between two to four hours, with one or more internal speakers and external speakers, followed by a buffet supper. The attendees hear some new ideas from the external speaker(s), and something about project management within the organization from the internal speaker(s). During the buffet supper they can meet other project managers and talk about what they are doing.

TABLE 17.2 Contents Page for a Procedures Manual

| ||

TriMagi | ||

| ||

Contents |

|

|

|

| Introduction |

|

| Program Management |

PM |

| Information Systems Project Management |

|

| Proposal and Initiation |

P0 |

| Definition and Appraisal |

|

| Develop work breakdown |

| P1 | Develop milestone plan |

|

| Work-package scope statements |

| P2 | Activity plans |

|

| Develop project networks |

| P21 | Define specification and configuration |

|

| Schedule resources and work |

|

| Estimate resource and material requirement |

| P213 | Update project network |

|

| Schedule project network |

| P214 | Produce resource and material schedules |

|

| Schedule cost and expenditure |

| P215 | Assess risks |

|

| Define controls |

| P216 | Appraise project viability and authorize |

| P22 | Contract and Procurement |

|

| Develop contract and procurement plan |

| P23 | Make payments |

|

| Execution and Control |

|

| Finalize project model |

| P233 | Execute and monitor progress |

|

| Control duration |

| P234 | Control resources and materials |

|

| Control changes |

| P235 | Update project model |

|

| Finalisation and Close-out |

| P236 |

|

| P24 |

|

| P25 |

|

| P256 |

|

| P26 |

|

P3 |

|

|

| P31 |

|

| P36 |

|

P4 |

|

|

| P41 |

|

| P42 |

|

| P43 |

|

| P44 |

|

| P45 |

|

| P46 |

|

P5 |

|

|

Appendices | ||

A |

| Project planning and control forms |

B |

| Supporting electronic databases |

C |

| Sample reports |

D |

| Staff abbreviations (OBS) |

E |

| Resource and material codes (CBS) |

F |

| Management codes (WBS) |

| ||

FIGURE 17.2 Pictorial representation of the stage, P2: Project definition.

FIGURE 17.3 Pictorial representation of the step, P21: Develop work breakdown.

Perhaps then a month or two later they have a problem, and remember talking about something similar with someone else, and can contact them. I have been an external speaker at events lasting two hours to two days.

A Vehicle for Learning. The community of practice can provide a vehicle for learning within the organization. Table. 17.3 is a model for organizational learning16 in which the organization uses the community of practice to identify its tacit knowledge and make it explicit, and having made it explicit can codify it, improve it, incorporate it into its procedures, and them make it tacit again through practice.

Supporting the Community of Practice. The community usually does not form spontaneously, and cannot survive without support from the organization. It needs top management support to start it in the first place, and provide it with a strategic budget in order for it to be able to continue. It should not consume much money. But it does use the time of the person currently running it, and so he or she must be freed from other duties. In a consultancy for instance, the leader of the community must be given an overhead cost code to book his or her time to. The organization of the events also takes money. As an external speaker, I always have my expenses paid and am occasionally paid a small honorarium. The buffet supper costs money, and there may be a need for limited technological support. The community must also be provided with clear leadership to ensure it works effectively and to encourage participation.

Reviews, Health-Checks, and Audits

Project reviews, including health-checks and audits are a way of improving performance on the current project, and learning from past success and failures to improve project management in the organization overall. I am going to discuss these more fully in the next chapter. For now I just want to say that the emphasis used to be on postcompletion reviews, and so the learning happened after the project was over. This contributed to the attenuation discussed in the next section, where learning is always put off. The emphasis now is much more on conducting reviews throughout the project, especially at the completion of project stages or major milestones.

Benchmarking and Maturity

The final practice for organizational learning is benchmarking, comparing your performance with others, to try to identify your weaknesses, and work on improving those areas. In its basic

TABLE 17.3 Nonaka and Takeuchi's Learning Cycle

| |||

| To | ||

|

| ||

| Tacit knowledge | Explicit knowledge | |

| |||

From | Tacit | Socialization | Externalization |

Explicit | Internalization | Combination | |

| |||

form you compare your performance with people doing similar projects. This can be with projects you previously did, other projects in your department, other departments within your parent organization, directly with competitors, or with people from entirely different organizations. In reality it is usually difficult to compare directly with your competitors, since they don't want you looking at their projects, but I am aware of benchmarking networks where direct competitors feel the benefit of comparing with each other outweighs the risk involved. An alternative, rather than comparing directly with each other, is to compare with an industry-wide database. The European Construction Institute (www.eci-online.org) and the Construction Industry Institute (www.construction-institute.org) jointly maintain a database of 4000 projects for process plant construction. So you cannot compare your project directly with a competitor's project, but you can compare with industry averages.

An alternative to direct benchmarking is to use a maturity model to assess your performance, and indeed this is now more common. The first was the capability maturity model (CMM) developed by the Software Engineering Institute (SEI) of Carnegie Mellon University for software systems deveopment.22 The original CMM model did not include project management, but the updated one, CMMI, did. PMI has now developed a maturity model for project management, the organizational project management maturity model (OPM3).23 With a maturity model you answer a series of questions to determine your performance against a series of parameters, which you can then plot in a spider web model in Fig. 17.4. You can then compare your current performance to the desired scores for the next level of maturity you are aiming for. You identify areas where you fall short and can then work on improving your performance in those areas, hopefully while maintaining your performance in the areas where you already exceed the requirement. This is performing a gap analysis for the organization directly comparable to what we did for individuals above.

Maturity and the Four Practices. Table. 17.4 contains a very simplified description of the five levels of maturity in SEI's CMM model. You will see at Levels 2 and 3 the organization works on improving its procedures and community of practice and at Levels 4 and 5 reviews and benchmarking. So the four practices I have described in this section directly contribute to maturity.

FIGURE 17.4 Spider web model.

| |

Level | Requirements |

| |

1 | Ad hoc processes, no guidance, no consistency |

2 | Procedures for individual processes, minimum guidance |

3 | Full procedures manual, group support |

4 | Processes measured, collection of experiences, and learning through reviews |

5 | Benchmarking, continuous improvement |

| |

Maturity and Organizational Performance. The concept of maturity does beg the question whether increasing maturity leads to increasing performance. Work in that area has been done at the University of California in Berkley.24 They found that increasing maturity did lead to increasing performance, as illustrated in Fig. 17.5. However, their results were not statistically significant, so they identified a trend but could not confirm it. Their performance curve followed a learning curve, so the performance improvement going from one level to the next is only half what was obtained coming for the previous level to this. But the cost of achieving the performance improvement is twice what it was at the previous level. Bill Ibbs and Justin Reginato defined a project management return on investment(PM ROI) as the performance improvement obtained divided by the cost of obtaining increased maturity:

![]()

The efficiency gain is the combined improvement from cost and schedule performance improvement. Unfortunately, the ROI from one level to the next is only a quarter of that from the previous level to this. Many western companies find it is not worth progressing from Level 3 to Level 4, whereas firms in low-wage economies find the improvement worthwhile. In low-wage economies the cost of achieving improvement is less because wages are less, but "annual project spend" is higher because material costs are higher. In China and India, a large numbers of companies have achieved Level 5 on SEI's CMM model. In the West, only very large, project-oriented organizations can afford to go for maturity Level 5. Companies doing fewer projects need to stick at Level 3.

FIGURE 17.5 Increasing performance with maturity.

Bill Ibbs and Justin Reginato also found that the cost of project management also varied with maturity. Organizations with maturity Level 1 spent on average 3 percent of project costs on project management. This rose to 6 percent for companies with maturity level 3, and fell back to 3 percent for companies with Maturity Level 5. There are two issues here:

![]() If you need to stick at maturity Level 3, you need to work on reducing the cost of project management getting it back to 3 percent.

If you need to stick at maturity Level 3, you need to work on reducing the cost of project management getting it back to 3 percent.

![]() This is a competency trap; organizations see the cost of project management increasing as they try to improve maturity, and do not want to spend more on project management, and so stay on low maturity.

This is a competency trap; organizations see the cost of project management increasing as they try to improve maturity, and do not want to spend more on project management, and so stay on low maturity.

17.4 IMPROVING ORGANIZATIONAL CAPABILITY

Anne Keegan and I found a four-step process for continuously improving organization project management capability25 (Fig. 17.6):

Variation. Through trial and error and practical experience, you identify new ways of managing and delivering projects. The project management community and top management can help in this process by identifying weaknesses in the current approaches and encouraging people to try new ideas. I discuss competency traps below, but you need to avoid blaming culture and encourage people to try new ideas and accept the occasional mistake for the long-term benefit of finding a better way of working. Audits, reviews, and benchmarking can also help pinpoint weaknesses and identify a need of variation.

Selection. Through review processes, you determine those new practices which provide benefit through improved performance, and those which don't. The project management community, reviews, and benchmarking can also help in the selection process.

Retention. Through procedures manuals, you store the selected new ideas where they are accessible. The selected new ideas then need to be retained centrally, perhaps by the project office (Chap. 16), perhaps through knowledge management processes (Sec. 17.5), or

FIGURE 17.6 Four-step process for improving project management capability.

perhaps through story-telling in the project management community. They cannot be retained on a project, because the project is going to be disbanded. That is the problem of projects as temporary organizations; they cannot own and retain knowledge, it has to be owned and retained separately from the project, and thus the need for the fourth step.

Distribution. Through project management procedures and the project management community you distribute the selected new ideas to project managers on projects where they can be used to improve performance on future projects.

The first three steps of this cycle were first described by people working on the evolution of species, explaining how new genes arise by random mutation, are selected through survival of the fittest, and retained in the gene pool. The model was subsequently adopted by the management-learning literature. In a functional organization the new ideas are generated in the functional hierarchy, selected and retained there, where they are immediately available for use by managers. But Anne Keegan and I identified that in a project-based organization there is the essential fourth step, distribution. In a project-based organization, new ideas are generated on one project which is going to come to an end, and so need to be transferred to a central pool where they will be held and from there to managers working on new projects, where they can be used.

Attenuation and Delay. Anne Keegan and I also identified two further issues with the four learning practices (Fig. 17.6). First there is a loss of learning at each step of the process. Terry Cooke-Davies has identified that there is a 25 percent loss of information at each step meaning that less than one-third of the good new ideas that a project-based organization generates actually end up being used on new projects.26 There are many ways suggested to overcome that problem:

![]() Make project reviews mandatory.

Make project reviews mandatory.

![]() Make the project office responsible for collating the results of reviews.

Make the project office responsible for collating the results of reviews.

![]() Use the intranet to store and distribute the good ideas.

Use the intranet to store and distribute the good ideas.

![]() Ensure the project management community is working effectively.

Ensure the project management community is working effectively.

The first three all add up to the bureaucracy of the organization, and so you have to balance the benefit of the knowledge management and innovation, against the cost of processing the data.

There tends to be a delay between each step:

![]() With post completion reviews, there may be a delay before ideas are selected and retained.

With post completion reviews, there may be a delay before ideas are selected and retained.

![]() It may be two years before the next edition of the procedures are issued.

It may be two years before the next edition of the procedures are issued.

![]() The project manager at the coal face may be too busy to read the new procedures until the start of his or her next project.

The project manager at the coal face may be too busy to read the new procedures until the start of his or her next project.

There is a concept of the viscosity of information. Some information oozes through an organization like treacle taking years to go from new idea to use on a new project. But other information zips through like gas through a vacuum. This is especially true of information entered into the intranet. It is immediately available for use, and so if there is no control on what information is entered, yesterday's hearsay can become today's received wisdom. The ideal is that there should be some delay with variation and selection, perhaps three months, allowing ideas to be properly tested and distilled, before being entered into the intranet, where they would be immediately available for reuse on future projects. The project office can manage this process. Other organizations are using the ideas of discussion rooms or "wiki" space. In a wiki space, individuals can enter ideas they have, describe how they solved a problem, or describe a new management approach they used. Other people can then comment on that idea, say whether they tried it, what experience they had, and how valuable they found it. The new ideas are then tested and selected through trial and discussion. New ideas can also be tested through the project management community in the same way.

An essential part of the above process is retention and distribution, and this falls within the wider area of knowledge management.

The Donald Rumsfeld Problem

There are four types of knowledge that need to be managed:

![]() That you know you have

That you know you have

![]() That you don't know you have

That you don't know you have

![]() That you know you don't have

That you know you don't have

![]() That you don't know you don't have

That you don't know you don't have

Conventionally, knowledge management has focused on just the first of these. But I suggest you should also think about how to discover the other three.

Know You Know. This is explicit knowledge you know you have. There are four questions which help you develop a knowledge management system:

1.Where are we? Establish an inventory of your current knowledge management practices.

2. Where do we want to be? Consider your knowledge management needs, what knowledge you need to improve performance. You need to identify your business context and drivers, the context within which your projects take place. Then you want to identify the success factors and key performance indicators relevant to your projects, which will tell you what you need to manage to improve performance, and so what knowledge you need. Then you need to identify the characteristics of the knowledge: what are the sources of knowledge, who are the users, and what are the enablers and inhibitors?

3. What is the gap? This will identify a gap between your current knowledge management practices and those you need.

4. What is the migration path? So you can then plan the project to develop the knowledge management systems you need.

This is gap analysis again (Fig. 2.1) sometimes known as the Y-model because the first two steps should be conducted independently, with the results coming together at the third to identify the gap. The first two steps should be independent because you don't want to influence the other; you don't want to define your requirements based on what you have got, or have your understanding of your knowledge inventory influenced by what you need.

The knowledge management system needs to consist of four processes:

1. Knowledge generation:

![]() What is the knowledge, where does it come from, and how is it captured?

What is the knowledge, where does it come from, and how is it captured?

![]() How is data converted to information, information to knowledge, and knowledge to wisdom?

How is data converted to information, information to knowledge, and knowledge to wisdom?

![]() How is knowledge distributed from where it is generated to where it is used?

How is knowledge distributed from where it is generated to where it is used?

3. Knowledge location and access:

![]() Where is it stored in repositories of data?

Where is it stored in repositories of data?

![]() How is it transferred to those who need it?

How is it transferred to those who need it?

4. Knowledge maintenance and modification:

![]() Who has the right to add to it?

Who has the right to add to it?

![]() Who has the right to change it?

Who has the right to change it?

Don't Know You Know. There are two types of knowledge that fall into this category: tacit knowledge and what I call "X-files" (Example 17.4 explains why). I described above how to use Nonaka and Takeuchi's cycle, coupled with the project management community to make tacit knowledge explicit and thereby make it known. This can also help identify knowledge through random connections, perhaps resulting in two seemingly unrelated ideas being put together. The X-files need to be found by data mining or careful archiving, and then they should be indexed so that files can still be found by the search engine on the intranet.

Example 17.4 X-files

In the first episode of the X Files, Mulder and Sculley think they have found new evidence of aliens. In particular they find a person with a device implanted in his ear. This device is conclusive proof, so they send it to FBI headquarters. In the last scene, a man is seen walking in the depths of the FBI basement past all the archive (X) files. He reaches a row, pulls out a box, and throws in the device, and there are already five or six in the box. The knowledge (truth) is not "out there," it is in the X-files in the basement of the FBI where nobody knows about it. Don't know they know.

Know You Don't Know. This is easier. Research can be done in the normal places: the internet (Wikipedia and Google), research journals, and books. Benchmarking and reviews can also help. Organizations also conduct research workshops to improve their own understanding of a particular situation. Project start workshops (Chap. 12) are in fact an example of such a workshop.

Don't Know You Know. You don't know to look for it and it is difficult to discover in structured normative ways. It requires random searches and random interconnections. Having people work together in cross-discipline teams can throw up new ideas. Encourage people to meet and talk at the water cooler.

Competency traps are things that stop us from learning. There may be a better, more efficient, or more effective way of working, but competency traps either stop us finding it, or stop us trying it even if we know it exists. In project-based organizations competency traps include the desire for safety and reliability, blaming culture, contracting practice, and so on.

The Desire for Safety and Reliability. You only have one shot at a project, and so there is often a preference for safety and reliability than efficiency and effectiveness. For instance, you may have two ways of doing something, one guaranteed to work with 100 percent efficiency and the other with 80 percent chance of success but 300 percent efficiency. The second way is on average two-and-a-half times better. But managers in project-based organizations often prefer the way that offers guaranteed success for the one time they are going to do it. If in a functional organization you are going to do it 100 times. The first 10 times you get it right 8 times and wrong twice, but be two-and-a-half times better off. The next 10 times you will have learnt from your mistakes and get it right 9 times and wrong once. From then on you will get it right every time and be 3 times better off. But in a project you only do it once and want it right that one time.

Blame Culture. This is related to the previous trap, but now looks at the decision from the perspective of the person making the decision, not the organization. If they work in a blame culture they will have an overriding preference for the safe, reliable option. Their assessment of the situation is different. If they choose the first option they have a certain chance of a quiet life. Nobody will notice. If they choose the second option they have an 80 percent chance of a quiet life, nobody will notice if it works. They won't get praised for the extra efficiency. But if it goes wrong they will get blamed, so they have a 20 percent chance of being hounded. They will choose the safe option.

In the early 1980s, I worked for a chemical manufacturer. There the attitude was if you don't take risks, you don't make profits, but if you take risks you make the occasional mistake. They therefore liked people who made the very occasional mistakes, and didn't like people who never made mistakes. People who never made mistakes weren't making profits. It was the exact opposite of a blame culture. Of course if you always made mistakes you got put on "special duties" and eventually shuffled offstage.

Contracting Practice. Standard contacting can be a competency trap. Don't expect a contractor on a remeasurement contract without a bonus to suggest a process improvement. They are going to lose profit. If you want your contractors to suggest improved ways of working, you need to offer them a bonus to do it.

Fear of Competitors Stealing Your Innovations. Some organizations don't innovate for fear that their competitors will steal their new ideas. It is a similar reason to why some organizations don't train their staff, for fear that they will leave and their competitors will get the benefit of the training. People are actually more likely to stay if they are properly developed. Enlightened organizations train their staff; enlightened organizations find ways of improving their processes. Yes their competitors will eventually adopt the ideas as well, but it will take them about two years, so the organization that does the research and development will always have two years lead.

Nonlinearity and Coupling of Projects. Projects are nonlinear coupled systems. To make improvements requires not just one bit to be changed on its own but the whole project to be changed. That can sometimes create complexity as it is difficult to design a new, integrated solution. Or it can create competition where each stakeholder wants to optimize the project outcome for themselves, resulting in an inferior outcome for the whole project. I discussed this in Chap. 3, when I discussed the need to obtain a balance of all the stakeholders' different objectives.

Traditional Project Management Thinking. One of the worst competency traps of all is traditional project management thinking. It preaches rigid control and certainty of estimates. Closing the estimates early can often lock you into high-cost solutions. Often, to find the best solution for the project requires you to keep options open for as long as possible, and that requires you to maintain uncertainty of the outcomes longer than you may be comfortable with. Rigid plans, with rigid control, can also lock you into high-cost solutions at an early stage.

1. Organizational capability comprises

![]() The project management body of knowledge

The project management body of knowledge

![]() An understanding of how to manage individual projects to deliver their objectives

An understanding of how to manage individual projects to deliver their objectives

![]() Technical and craft skills

Technical and craft skills

2. The project management body of knowledge comprises

![]() The project life cycle

The project life cycle

![]() The management cycle

The management cycle

![]() The project management functions: scope, organization, quality, cost, time, and risk

The project management functions: scope, organization, quality, cost, time, and risk

3. Project management competency is

![]() Knowledge

Knowledge

![]() Skills

Skills

![]() Personal characteristics

Personal characteristics

![]() To perform in accordance with defined standards

To perform in accordance with defined standards

4. Different levels of management require different profiles of competence. Lower levels require more technical competencies. Higher levels require more people and strategic competencies.

5. Competence is assessed by gap analysis, comparing current competence to desired levels for future development.

6. There are three development horizons for individuals and organizations:

![]() Long-term career plans and succession strategies

Long-term career plans and succession strategies

![]() Medium-term education and experiential development

Medium-term education and experiential development

![]() Short-term specific competency training

Short-term specific competency training

7. The first two of these need to be aligned with the line having time horizons longer than projects and the third with the project.

8. There are four practices for developing organizational capability

![]() Procedures manuals

Procedures manuals

![]() A project management community of practice

A project management community of practice

![]() Reviews

Reviews

![]() Benchmarking

Benchmarking

9. There are four processes for developing organizational capability

![]() Variation

Variation

![]() Selection

Selection

![]() Retention

Retention

![]() Distribution

Distribution

10. There are four steps for assessing knowledge management needs

![]() Assess where you are.

Assess where you are.

![]() Define where you want to be.

Define where you want to be.

![]() Determine the gap.

Determine the gap.

![]() Develop a knowledge management plan to close the gap.

Develop a knowledge management plan to close the gap.

11. There are four steps of knowledge management

![]() Generation

Generation

![]() Transfer

Transfer

![]() Maintenance and modification

Maintenance and modification

12. There are six competence traps in project-based organizations:

![]() Desire for reliability

Desire for reliability

![]() Blame culture

Blame culture

![]() Contracting practice

Contracting practice

![]() Fear of competitors stealing ideas

Fear of competitors stealing ideas

![]() Nonlinearity and coupling of projects

Nonlinearity and coupling of projects

![]() Traditional project management systems thinking

Traditional project management systems thinking

1. Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 3d ed., Newtown Square, PA.: PMI, 2004.

2. International Project Management Association, IPMA Competence Baseline: The Eye of Competence, 3d ed., Zurich: International Project Management Association, 2005.

3. Association for Project Management, The APM Body of Knowledge, 5th ed., High Wycombe, 2006.

4. Turner, J.R (ed.), People in Project Management, Aldershot, U.K.: Gower, 2003.

5. Turner, J.R and Wright, D., The Commercial Management of Projects, Aldershot, Gower: 2009.

6. Office of Government Commerce, Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2, 4th ed., London: The Stationery Office, 2005.

7. Payne, J.H. and Turner, J.R., "Company-wide project management: the planning and control of programmes of projects of different types," International Journal of Project Management, 17(1), 55–59, 1999.

8. Turner, J.R. and Müller, R., Choosing Appropriate Project Managers: Matching Their Leadership Style to the Type of Project, Newtown Square, PA.: PMI, 2006.

9. Boyatzis, R.E., The Competent Manager: A Model for Effective Performance, New York: Wiley, 1982.

10. Spencer, L.M.J. and Spencer, S.M., Competence at Work: Models for Superior Performance, New York: Wiley, 1993.

11. Gonczi, A., Hager, P., and Athanasou, J., The Development of Competency-Based Assessment Strategies for the Profession, Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1993.

12. Engineering Construction Industry Training Board, National Occupational Standards for Project Management, Kings Langley, Herts, U.K.: Engineering Construction Industry Training Board, 2003.

13. IBSA, Volume 4B: Project Management. In: BSB01 Business Services Training Package Version 4.00, Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia: Innovation and Business Skills Australia, 2006.

14. PMSGB, South African Qualifications Authority Project Management Competency Standards: Levels 3 and 4, Pretoria, South Africa: South African Qualifications Authority, 2002.

15. Crawford, L.H., "Assessing and developing the project management competence of individuals," In: Turner, J.R. (ed.), People in Project Management, Aldershot, U.K.: Gower, 2003.

16. Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H., The Knowledge-Creating Company, New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

17. Kolb, D. A., Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1984.

18. Turner, J.R., Huemann, M., and Keegan, A.E., Human Resource Management in the Project Oriented Organization, Newtown Square, PA.: Project Management Institute, 2007.

19. Keegan, A.E. and Turner, J.R., "Managing human resources in the project-based organization," In: Turner, J.R. (ed.), People in Project Management, Aldershot, U.K.: Gower, 2003.

20. Payne, J.H. and Turner, J.R., "Company-wide project management: the planning and control of programmes of projects of different types," International Journal of Project Management, 17(1), 55–59, 1999.

21. Crawford, L.H., Hobbs, J.B., and Turner, J.R., Project Categorization Systems: Aligning Capability with Strategy for Better Results, Newtown Square, PA.: Project Management Institute, 2005.

22. Paulk, M.C., Weber, C.V., Curtis, B., and Chrissis, M.-B., The Capability Maturity Model: Guidelines for Improving the Software Process, Boston: Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing, 1995.

23. Project Management Institute, Organizational Project Management Maturity Model, Newtown Square, PA.: Project Management Institute, 2003.

24. Ibbs, C.W and Reginato, J., Quantifying the Value of Project Management, Newtown Square, PA.: Project Management Institute, 2002.

25. Keegan, A.E. and Turner, J.R., "The management of innovation in project based firms," Long Range Planning, 35, 367–388, 2002.

26. Cooke-Davies, T.J., Towards Improved Project Management Practice: Uncovering the Evidence for Effective Practices through Empirical Research, PhD Thesis, Leeds,: Leeds Metropolitan University, 2000. Available: www.dissertation.com.