![]()

5.

Innovating for the Future

The enterprise that does not innovate ages and declines. And in a period of rapid change such as the present, the decline will be fast.

—Peter Drucker

Throughout this book we’ve offered ways for you as a leader to look ahead: whether you’re setting a vision, crafting a competitive strategy, developing your team, or demanding better results, you are constantly pushing your team, unit, or organization into the future. In this chapter, we’ll focus on how to establish the mechanisms and culture of innovation that increase the chances for growth and sustained performance over time.

Organizations that sustain their success consistently over the long term can be hard to find. Consider the experience of the Ford Motor Company. The iconic company struggled with years of red ink until the early 1990s, when its management revitalized product development, reawakened the organization’s deeper purpose, and produced what Collins and Porras described in Built to Last as “a remarkable turnaround.” Twenty years later, though, the company was again verging on bankruptcy due to structural cost disadvantages, slow reactions to market shifts, and a general lack of innovation. Then in 2008, it was rescued and transformed once more by CEO Alan Mulally, emerging as one of the world’s most profitable car companies. Three years later, after Mulally’s departure, more struggles ensued as Ford’s profits and share price began to flatten. In 2016, the board fired the successor CEO, fearing the company was not positioning itself to survive in an industry being revolutionized by self-driving and electric vehicles.

Ford has managed to survive through these up and downs, but many companies don’t. The average life span of an S&P 500 company has decreased from sixty-plus years in the 1950s to around seventeen years now. In his HBR article “The Scary Truth about Corporate Survival,” Vijay Govindarajan reported on research at Dartmouth that looked at the longevity of almost 30,000 companies listed on US stock markets from 1960 to 2009 and found that companies that were listed before 1970 had a 92 percent chance of surviving the next five years, whereas companies that were listed from 2000 to 2009 had only 63 percent. According to the Small Business Administration, only 50 percent of small businesses last five years, and only 33 percent make it to a tenth anniversary. Most researchers say that nonprofits fail at about the same rate. Similarly, according to research by Boston investment firm Cambridge Associates, data suggests that 60 percent to 80 percent of all startups fail after five years, a rate somewhat higher than that of small businesses.

So why is sustained business success so ephemeral for most companies and many leaders? Every rise-fall-rebirth-fall-again story has its own particulars, but in the end, there are always two villains in the plot.

The first is external: even after a company has successfully transformed itself, markets will continue to shift, often suddenly; new technologies will emerge; and global economic shocks will periodically rock the system. When Mulally was heroically saving Ford, who could have predicted that within a few years, the company would see the explosive success of Tesla, the proliferation of ride-sharing transportation, or the accelerating progress of self-driving cars?

The second villain is internal: success breeds complacency, inward focus, and even arrogance. As your unit or company keeps winning, belief in the status quo hardens: “if we’ve done something well, there’s no need to change.” And that belief is only strengthened by cheerleaders—short-term investors, stock market analysts, exuberant customers—who keep urging you to do more of the same and not take bold moves that might rock the boat. Boston Consulting Group president and CEO Richard Lesser observed to us that most CEOs get trapped by their own success. They get accolades for a successful transformation or improved results, but then they aren’t willing to take a hammer to what they have created and to transform it again to get to the next level. “In some ways you have to be able to start all over again periodically,” he advises. “But you also have to instill that mindset into the organization so that there’s always a healthy dissatisfaction with the status quo.”

Overcoming these challenges is critical, whether you are heading a large enterprise, launching a startup, or leading a part of a bigger company. Sustaining your business into the future is a vital component of achieving impact. And for rising leaders, there’s no better way to build the innovation skills and mindset you’ll need at higher levels of an organization than to practice them hands on. You’ll be able to make your mistakes and learn from those at smaller scale. And indeed, opportunities for innovation exist at all levels. If you’re now heading a company division, a business unit, or even a small team, you need to understand how that team contributes to the overall organizational portfolio of today’s cash and tomorrow’s reinvention. And you need to be able to sustain your own part of the business into the future as well.

This is particularly true because a great deal of corporate innovation is bottom-up—it’s not simply directed by a CEO or invented by an R&D department. Frontline leaders working closely with customers, suppliers, or other partners are exposed daily to different needs and opportunities in the market, new approaches to working, and insights about competitors, new technologies, and business-changing trends. Embrace these relationships for what they can teach you about the future of the business you lead now, as well as the broader organization that you may lead in the future. Also, innovation exploration is not just for customer-facing managers. If you’re leading a corporate function—finance, legal, technology, human resources, and so on—seek out opportunities to revolutionize processes or restructure costs for your group. Whatever your leadership level or role, try to learn something that may catch the eye of more senior managers and perhaps become a showcase for next year’s broader corporate strategy.

There are four specific elements of this practice of actively championing future-focused innovation:

- Balancing the present and future: creating bandwidth to focus on the future while still maintaining high performance in day-to-day operations

- Getting ready for the future: developing the mindset, the funding, and the market intelligence to invest wisely in future-oriented areas of the business

- Shaping the future: driving the innovation, experimenting, and learning to move your organization into new territory

- Building a future-focused culture: infusing your organization with the skills, beliefs, and values to innovate well and to keep innovating and reshaping itself over and over again

As with all of the practices in this book, we do not mean that the steps we describe in these areas constitute a linear formula, but rather starting points for your own journey toward creating a sustaining enterprise. To give you a sense of what this means in practice, let’s look at the experience of Jim Smith, CEO of Thomson Reuters, a leading provider of news, technology, intelligence, and expertise to finance, law, and other professional industries.

Building sustaining success at Thomson Reuters

When Jim Smith was promoted to CEO of Thomson Reuters in January 2012, he took the reins of a $13 billon global news and information powerhouse whose businesses included the Reuters news service; the world’s largest publishing company and information resource for the legal profession; a Financial & Risk business that provided terminals and data feeds for major banking and trading institutions; a unit that served as the primary source of legal, regulatory, and compliance information for the tax and accounting profession; and an Intellectual Property and Science business that helped universities and researchers track and search scientific findings and patents.

Smith’s most urgent challenge was to fix the Financial & Risk business, which was by far the largest in the company and had been losing share in a shrinking market for five consecutive years. The recession and financial crisis of the previous years had decreased demand for the terminals that were the bread and butter of the division’s revenue. In his first year, Smith spent a significant portion of his time working with the Financial & Risk leaders on investments and strategies to turn the business around and achieve maximum sustainable growth and shareholder value.

In addition to his focus on the Financial & Risk unit, Smith spent time with the other business units to review their financial performance, growth plans, and resource requests. He also visited dozens of customers around the world, both to strengthen their relationship with Thomson Reuters and to better understand their challenges.

Early into the job, Smith concluded that he would need to change the way Thomson Reuters was managed—from a portfolio of individual operating companies into a far more integrated, less complex, and higher-growth enterprise. The organization had been built over more than a century through acquisitions, divestitures, combinations, and spinoffs (including 300 acquisitions in the previous ten years), and each of these structural changes brought different practices, systems, and ways of working. As a result, the company was overly complex, expenses were duplicated, processes were fragmented, technology was not being leveraged, leaders of the different businesses weren’t learning or benefiting sufficiently from each other, and large enterprise customers needed multiple touch points and contracts to work with the company. Furthermore, this complexity made it more difficult to deliver the full breadth and depth of Thomson Reuters’ capabilities across customer segments and diverted resources away from developing the technology and products of the future.

To address these issues, Smith set out to create an integrated, customer-focused enterprise that could take advantage of its scale and fuel its growth more through organic innovation than acquisitions—a transformation that would take a number of years.

During 2012, he began laying the groundwork for this transformation. He engineered the sale of a health-care business and some smaller businesses because they would not be key contributors to future growth. At the same time, he and his team approved and completed a number of small technology acquisitions to complement their existing digital platforms, such as an online brand protection company and a provider of electronic foreign exchange trading solutions.

While these steps helped sharpen the company’s focus on its core businesses, they didn’t directly move Thomson Reuters toward greater integration or organic growth. To do that, Smith concluded, he first needed managers to start tackling the organization’s complexity.

During 2012, Smith’s chief financial officer had found forty-two different billing systems that he consolidated into one. Aiming to replicate this effort, Smith made simplification and standardization a major priority for the company beginning in 2013. He added the newly created position of Chief Transformation Officer to his executive committee, a function that would eventually oversee nearly a third of the company’s spend and head count, and publicly committed to investors that the company would reduce complexity-related expenses by $400 million by the end of 2017.

As the Financial & Risk division stabilized, Smith turned more of his attention toward the longer-term transformation of the company. As part of this shift, he worked with his staff to streamline the corporate operating rhythm to reduce redundant meetings, rationalize his personal calendar, and make way for even more time with customers.

To kick-start organic growth, Smith launched a number of innovation initiatives, coordinated by a central innovation team, to build a more flexible, dynamic, and forward-thinking culture inside the firm. A small but early and important success story came in the form of the Catalyst Fund. This fund, set up by the corporate center, awarded seed money to individuals or teams that wanted to pursue potentially breakthrough new ideas, either in the form of new offerings or improved processes. Anyone could submit an idea, and the most promising were put in front of a review board once a month, chaired by Smith himself. Those who passed the first round of reviews used their funding to build proofs of concept that they could test with customers and then iterate upon. The most promising ideas emerging from this process would then be more fully funded as new products and services. Smith also asked his leaders to designate “innovation champions” throughout the organization to be involved in cross-company innovation initiatives, introduced future-focused metrics into business reviews, and established communications avenues and a yearly workshop where organic innovation activities could be discussed, coordinated, and celebrated.

Smith accompanied the innovation program with a deliberate initiative to make the company’s culture more creative and collaborative. All managers and leaders, starting with Smith’s executive team, went through a workshop and follow-up discussions meant to create a common language and expectations for behavior, which then were reinforced in performance reviews and promotion decisions. Smith also came to grips with the fact that several of his senior business unit heads and functional leaders had not fully bought into the idea of an integrated operating company and were not truly collaborating with each other, so he replaced several of these blockers at the same time. This gave Smith a more collaborative team and sent a strong signal through the company that everyone should take the culture of innovation and collaboration seriously.

By the end of 2014, Smith’s transformation was beginning to bear fruit. Higher customer satisfaction and employee retention ratings were paired with a significant improvement in year-over-year net sales. The Financial & Risk business recorded its first year of positive net sales since the recession. Areas of the business targeting faster growth opportunities saw 4 percent aggregate revenue growth. And the simplification program improved operating efficiency and was on track to reach its savings targets.

Smith’s efforts to position the company for the future have not let up since then. In recent years, the company has established a network of innovation labs around the world from Cape Town, South Africa, to Waterloo, Canada, where the company’s technologists can work side by side with customers, partners, and startups, rapidly prototyping solutions. The company also formed partnerships with blue-chip technology firms like SAP and IBM Watson to power its solutions. In late 2016, Smith announced the creation of a new flagship technology center housing up to 1,500 staff in Toronto to take advantage of the growing concentration of engineering and technical talent in Canada’s Silicon Valley and moved his headquarters there to reinforce the commitment. One year after the announcement, the company has hired over 200 technologists and data scientists, and announced a more than $100 million investment in a permanent facility for the center. And in early 2018, as a result of the successful efforts to turn around the Financial & Risk business, Smith sold a fifty-five percent stake in it to the Blackstone Group for $17 billion, giving Thomson Reuters greater financial flexibility to transform even further into the future.

In the six years since Smith became CEO, Thomson Reuters has become a vastly different company, now focused, as Smith puts it, at the intersection between commerce and regulation. As such, Thomson Reuters strives to help businesses of all sizes—from solo practitioners to global corporations—find answers to their most pressing problems. Along the way, the company has become more focused, more profitable, faster growing, and on the list of most admired and most desirable firms to work for. And while no company’s future is ever guaranteed, Thomson Reuter’s future seems more promising than ever.

Balancing the present and future

One of the biggest challenges for leaders is maintaining the continued operation of the core business or of their unit while also looking ahead to avoid future threats and create opportunities for future growth. While it’s easier to focus on one or the other, as a leader, you must do both, even if you are working in a midlevel role and are primarily responsible for generating cash or other near-term operational results. Whatever your role, if you give all your attention to your everyday core, you can get mired in details and miss longer-horizon threats and opportunities. But if you veer toward too many blue-sky ideas and make major investments in them, you will miss next quarter’s numbers or neglect key customers, threatening the success and longevity of your unit, as well as your own career. Achieving this balance is in part a logistical matter of making time for you to focus on innovation and, in part, a conceptual question of how to balance current and future work throughout the organization.

Creating bandwidth to focus on the future

Freeing up your time from being totally absorbed in day-to-day activities is a critical part of getting ready for the future. A leader can easily be so focused on current challenges and problems that there is no time to think about the next quarter, much less the next decade—think of Stephen Covey’s dictum that the urgent drives out the important. This is one of the most pernicious traps that leaders fall into and that reduces their ability to create a sustaining enterprise, because if you focus on the future too late, it’s already here and you’re behind the curve. So while all of the steps that we described in the “getting results” practice in chapter 4 are critical, doing them at the expense of time to deal with the future is counterproductive.

Consider, for example, Jim Smith’s move to reshape Thomson Reuters’s operating rhythm to free up more of his own time for thinking, planning, and connecting with customers. This kind of shift is necessary in companies of all sizes. Yaron Galai, the founder and CEO of digital media startup Outbrain, did the same thing when his company reached a significant threshold of growth, and he realized that he no longer had enough time to focus on both managing the current business and figuring out the next chapter. As a result, he brought in an experienced operational leader who had been on the board to serve as a co-CEO, which allowed him to focus on the future of the company.

Finding bandwidth is often about personal discipline as much as organizational cadence. That kind of discipline is necessary for good leaders at every level: for example, Jane Kirkland, senior vice president of State Street Corporation, is relentless about organizing her time to make sure she doesn’t get buried in day-to-day activities: “I work off of a regular list of to-dos that I keep, but I always categorize them across different time horizons, aligned with the people I’m holding accountable for different tasks.”

We often see leaders struggling to have the humility to admit that they can’t do it all, as if that is a black mark on their leadership. Instead, we urge leaders that we work with to see that this is the very hallmark of strong leadership: recognizing how to apportion tasks, roles, and areas of ownership to others to create the highest levels of performance for the organization overall.

Taking a portfolio approach to innovation

When you move your unit or team toward a dual focus on current business results and future innovation, tensions and trade-offs are inevitable. As innovative opportunities emerge, when and how much do you start favoring them over existing operations? If certain core business initiatives are flattening out, when do you cut back on investment? If certain experiments don’t work out, do you discard them or double-down with even greater commitment? And how do you prevent the new future from cannibalizing what you need to keep going today? These questions are the essence of the “innovator’s dilemma” that Harvard Business School professor Clay Christensen highlighted in his book of the same name—where the success of innovation threatens the existing business and may result in trade-offs that stifle the innovation.

To manage this tension, consider the model of financial portfolio management: instead of putting all of your money in one place, you spread it around and create a diverse portfolio of different types of investments—stocks, bonds, small cap, large cap, domestic, international, and so on. You then manage the risk and return in the portfolio by adjusting the mix and amount of investments dynamically, since it is unlikely that all of them will rise or fall to the same degree simultaneously. We can apply this concept to innovation as well. Tuck School of Business professors Vijay Govindarajan and Chris Trimble, in their HBR article “The CEO’s Role in Business Model Reinvention,” describe their “three box” approach. They argue that leaders need to balance and then continue to rebalance their investments between what should be “preserved and improved” in their current business, what should be “destroyed” because it is underperforming or has little upside, and what should be “created for the future.” Their research suggests that most leaders significantly overweight their focus and investment on preservation, and don’t put enough thinking and resources behind what should be destroyed and created for the future.

The portfolio idea extends beyond simply balancing riskier, long-range projects with low-risk, near-term growth. Even within their more innovative projects, companies such as Google, Intuit, 3M, P&G, and Apple don’t put all their eggs in one basket. Instead they create portfolios of innovation projects, including some core initiatives and also innovation of different types, technologies, and markets. The companies then actively manage these portfolios by allocating resources differentially, periodically killing some projects while doubling down on others. One of the reasons that companies struggle with innovation is that they don’t manage the portfolio of projects with enough rigor or discipline, allowing poorly performing efforts to continue while starving those with more potential.

You can organize your innovation portfolio along a number of different axes. One way is to include projects with different time frames. As Robert Schaffer and Ron Ashkenas described in their book Rapid Results: How 100-Day Projects Build the Capacity for Large-Scale Change, adhesives maker Avery Dennison used a framework developed by McKinsey that separated projects by time horizons: horizon one projects were short-term innovations (less than two years) that would use existing proprietary technology; horizon two were medium-term innovations (two to five years) that required modifications of existing technology; and horizon three were longer-term (more than five years) breakthroughs that required significant new research and development. (You can find numerous examples of horizon charts online.) Plotting projects in this way revealed to then-CEO Philip Neal and then-president Dean Scarborough that the company’s investments were too heavily weighted toward longer-term projects that wouldn’t pay off for many years (even if they were successful). To decrease risk, Neal and Scarborough shifted much more focus to horizon one projects that could pay off in the short term and provide a basis for funding the longer-term and more speculative initiatives.

Another way to measure your innovation projects is by focus area. For example, Thomson Reuters categorizes its innovation projects in terms of whether they will affect operations, customer experience, or product offerings. In each of these buckets, it also looks at how close or far the projects are from the current core, which is another way of assessing the time frame and potential return on the innovation. The company’s Senior Vice President of innovation Katherine Manuel then maps out the existing innovation projects and reviews them periodically with the corporate leadership team so that they can decide how to balance their investments and expectations. As she notes, “It’s important to have a portfolio of experiments being run that impact all types of innovation and all areas of the company.”

At TIAA, the leading provider of financial services for the academic, research, medical, cultural, and government fields, CEO Roger W. Ferguson Jr. considered the parts of the business that needed to be sustained, both of which needed to evolve when building his portfolio. He would frequently cite, for example, the importance of preserving the integrity of the company mission: “We were founded to ensure that teachers could retire with dignity. Providing a secure retirement remains our purpose, but we now serve millions of others working to serve society in the nonprofit sector, and we strive to deliver financial well-being throughout all stages of life.” At the same time, Ferguson also emphasized that the new TIAA had to be simpler to continue meeting its customers’ needs, so it had to let go of old ways of thinking. Part of that was a decision to rebrand the company to the shorter identifier “TIAA,” moving away from its old name (the company had been TIAA-CREF: think of Govindarajan and Trimble’s first box—preserve and improve). In line with its drive to simplify, TIAA took a fresh look at its existing processes; in one case, it was able to cut a fifteen-day process down to two-and-a-half days. The value to customers was clear: the change reduced the number of customer phone calls by hundreds of thousands (thus, Govindarajan’s box two—letting go of things now getting in the way of the future). In step with the new identity, Ferguson also accelerated growth across the company’s nonretirement businesses. To do that, Ferguson commissioned a number of strategic growth teams to problem-solve new opportunities and develop new offerings, most recently resulting in the acquisition of EverBank, which will allow TIAA to meet the financial needs of its customers in a comprehensive way for generations to come (box three—create). Juggling all of this together—with a portfolio mindset—was critical for Ferguson’s success.

Taking stock of your project portfolio periodically, therefore, is a critical step for embracing the future and creating a sustaining enterprise.

Getting ready for the future

In addition to carving out time to focus on the future, you must also prepare for it in other ways. To innovate, you need resources and information about threats and opportunities to guide your idea generation and experimentation. You can develop both of these as part of your unit’s or team’s day-to-day work.

Build current surplus to fund the future

Investing in the future requires that you first generate cash from your current operations. We saw this in the Thomson Reuters case: Smith reduced costs through simplification and focused on the turnaround of the Financial & Risk business at the beginning of his tenure. In other words, tightening up your execution and improving margins of your existing business is a good place to start. That’s what John Lundgren, CEO of Stanley Black & Decker, did to raise the funds to buy several other companies at the outset of its multiyear growth plan. And whatever the scale of your business—whether you run a small venture or a unit within a larger company—operating ever more efficiently puts money in the bank for future growth and investment. But let’s also look at two other ways to create some surplus for longer-term bets: developing product and market extensions (adjacencies) to generate more revenue from current operations and selling off or stopping lower-performing business areas.

Incremental innovation through adjacencies

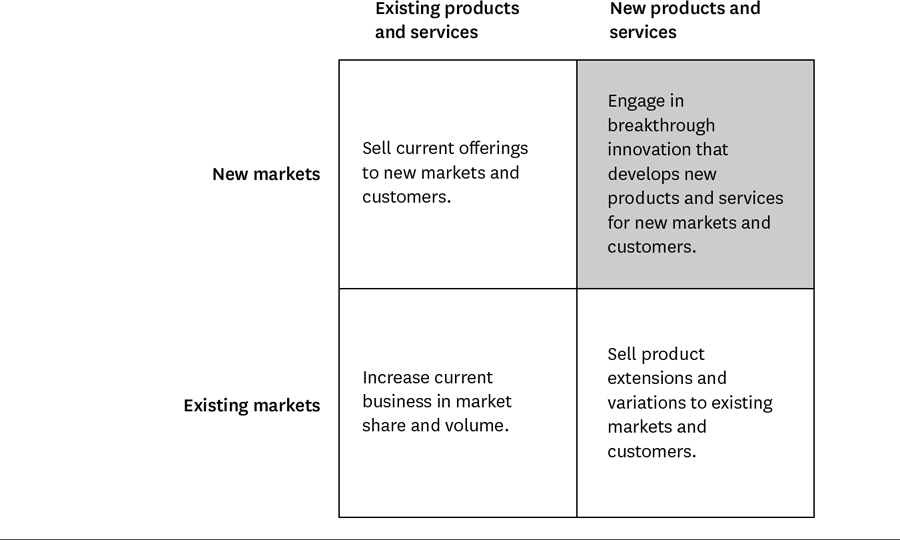

Incremental innovation based on your current offerings is a common—and often lower-risk—way to build investment cash. Consider the matrix of products and markets in figure 5-1. With this framework, you can ask your business leaders (or even team members) to identify existing products or services that you could potentially introduce into new markets, and existing markets that would benefit from extensions or variations on your existing products. These categories of incremental innovation (the two shaded areas on the matrix) are called adjacencies. At TIAA, selling existing products to new professional groups (such as hospital staff) was a market adjacency, while diversifying investment and retirement options for existing higher ed customers was an example of a product extension. At Thomson Reuters, a major adjacent opportunity was to sell existing products to new geographic markets around the world, so it created a global growth organization with the specific objective of doing that.

Divesting

Another way to free up cash and resources to invest in future opportunities is to sell off or close products, units, or parts of your business that don’t create great returns today and are likely not part of the future business. What’s difficult about this is not identifying which areas are ready for the chopping block, but rather setting aside your and others’ emotional investment in an area that was at one time important for the business (or in former days was its own pioneering breakthrough; once again, the problem of the innovator’s dilemma). But when the time comes, making the break is critical, as a way of freeing up both funds and other resources and your own attention.

For example, when Satya Nadella became CEO of Microsoft in 2015, he sold off the company’s failing acquisition of Nokia’s mobile handset division, realizing that it was not going to catch Apple or Google in smart phones. The money from the sale helped support Nadella’s future growth strategy of moving Microsoft into more applications and services and becoming a more major player in cloud-based computing. Similarly, Smith at Thomson Reuters sold a health-care business and later the larger Intellectual Property and Science business because they were no longer at the core of the enterprise growth strategy. He also sold a major stake in the Financial & Risk business as a further way to build capital for the future.

Scan the horizon for breakthrough innovation

As you generate the cash, you also must be continually considering how to invest it, based on both potential opportunities and threats on the horizon. Your work in setting a vision and a strategy should give you a sense of this, but even apart from those specific practices, your understanding of a bigger picture for your business can help you identify particular areas for innovation. While some of the areas might be in the adjacency boxes depicted in figure 5-1, others might be in the upper-right quadrant—so-called breakthrough innovation, depicted in figure 5-2. Let’s consider that now.

So-called breakthrough innovation involves a bigger leap (and usually a bigger risk-return profile) toward the future. As a leader, you must expand your awareness of new and more ambitious possibilities. Do so by scanning externally for new technologies, emerging new social or economic paradigms, or cutting-edge ideas in other industries that you could adapt. Be bold and creative in your investigations: start by engaging with customers, partners, and industry experts to find out what they are seeing or developing for their businesses. For example, CEO of Chevron Mike Wirth meets regularly with economists and other specialists to understand long-term scenarios for the price of oil and the latest advances in renewable energy technology. He also keeps tabs on more speculative ideas, for example, how the rise of ride sharing and electric cars could alter energy retailing. CEO of Bumble Bee Seafoods Chris Lischewski has participated in a futurist university program to better understand how broader social and economic trends among young consumers might open up future opportunities for marketing seafood.

Depending on your field, scanning could also include reading specialized research, talking to influencers in your field, or making benchmarking visits to noncompetitive visionary companies willing to share how the latest technology is changing their business. Car companies today meet with university researchers and automation boutiques to get ideas about self-driving and alternative transportation technologies. Other companies troop to Google, Facebook, and Amazon to learn about trends in robotics, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality, probing for implications for their own next generation of products. Many companies are also investing in mining big data of public and consumer information to analyze trends and opportunities in customer behavior.

While much of this work requires you to look outward, don’t neglect your own backyard. Talking to people throughout your unit or organization—especially those on the front lines—will help you discover weak and not-so-weak signals about where your market is headed. Your best salespeople will be aware of changing customer tastes and competitors’ innovations, and your engineers or product people often have strong relationships with other insightful industry practitioners. Leading innovation means listening to your own people as much as guiding them on what to do.

It can be exciting to identify possible opportunities, but you need to be clear-eyed about the threats as well. Anne Mulcahy’s turnaround of Xerox, for example, was partly fueled by her personal understanding of how competitors were leapfrogging the company’s products and services with a superior value proposition, an understanding she drew from her days working in sales. Paula Kerger’s multiplatform strategy for children’s programming was developed partly because she realized how much digital educational content was now encroaching on broadcast viewership and the traditional business model of PBS. At TIAA, the business model threat came into focus for Ferguson when he analyzed the company’s longer-term payout viability and realized that baby-boomer retirements could impact the long-term financial strength of the company.

As a leader, you can never become complacent or let your team become satisfied. By incorporating this kind of scanning into your daily work, you’ll prime your team or unit to take advantage of opportunities and avoid threats—right away.

Shaping the future

How do you act on the opportunities and threats you’ve identified in your operating environment, once you have the resources in place to do so? Innovation should not be just a random exercise in brainstorming and trying things, but an intentional approach to evolving the company toward a significantly new value proposition and relationship with customers, while also sharpening and learning more about the value proposition along the way.

At Thomson Reuters, the new Catalyst Fund encouraged managers to pursue systematic and disciplined organic innovation through incremental steps and ongoing learning from customers. To secure the money, teams filled out a simple two-page application, describing the idea, its potential payoff, what would be needed to make it happen, and how the initial funds would be used. Applications were screened first by innovation champions and then a Catalyst Fund panel—a sort of corporate shark tank—composed of Smith and several members of the executive team. The committee met monthly, both to decide on these new applications and to see the output of projects in which it had previously invested.

Once the innovation leaders began to get traction in their own businesses and functions, and the bosses understood that innovation was now part of their jobs, ideas and innovation opportunities started to emerge from all corners of the organization. For example, Adam Quinones, a manager in the Financial & Risk business, used the Catalyst Fund process to propose and then develop an app to enable mortgage-related document and data validation, risk and liquidity assessment, and customer data and document storage for the commercial real estate industry. After building a prototype, Quinones organized a forum for potential customers to test the product. Based on the customers’ feedback and enthusiasm, Quinones was able to refine the product and begin to sell it, creating real value to customers and a supercharged revenue stream for the company.

Every team’s and company’s situation is different, and there is no one-size-fits-all approach for transforming innovative ideas into breakthrough growth engines. You will need to develop your own process. But three ways of thinking about innovation should inform it: getting a jump on disruptive innovation, leveraging the lean startup approach, and embracing failure in the service of learning.

Disruptive innovation

Harvard Business School professor Clay Christensen first coined the term “disruptive innovation.” As he describes, disruptive innovation is a process by which a smaller competitor quietly develops a new business model and, in so doing, suddenly shifts the competitive dynamics of an entire industry and its well-established companies. A classic example is Netflix’s transformation of the video rental industry, undercutting Blockbuster’s business by using the US mail to deliver DVDs straight to customers, with no due dates, late fees, or crippling real estate costs. Netflix then disrupted the movie and broadcast television industry by offering on-demand content for a subscription fee.

In contrast, Christensen defines “sustaining innovation” as continual experimentation to improve and refine an existing business model. While sustaining innovation can provide substantial incremental growth, mastering disruptive innovation means that incumbent companies are more prepared for unanticipated threats and better able to transform as technologies and new ideas around them develop. Mastering disruptive innovation also can help startups launch themselves into established markets.

As a leader in an established company, you need to realize that unusual and often unseen competitors can disrupt your business at any time. If you are in a startup and can find the right business model, you can be one of those disruptors. Particularly because of the enabling aspects of digital infrastructure, you often don’t need large amounts of capital to enter established markets, but can instead find ways to pick off customers at the margins. As more and more free information becomes “good enough,” Thomson Reuters, for example, uses its innovation mechanisms to identify specific market needs that it can meet with slices of professional data that come available directly or through partnerships with startups.

If you run an established company or division, one way to prevent your own business model from being disrupted is to develop disruptive ideas yourself. In their HBR article “Meeting the Challenge of Disruptive Change,” Christensen and Michael Overdorf explain that doing this is usually difficult because your resources, processes, and decisions about priorities and investments are geared to the existing business and won’t accommodate or support an idea that doesn’t fit the current framework. To overcome that and avoid the rejection of disruptive ideas out of hand, you can set up a special team of dedicated resources, separate from the existing business processes and pressures, to focus on the new idea. For example, several years ago, a large pharmaceutical company that one of us worked with set up a small full-time team, led by a senior executive, to explore the development of an industrywide data analytics business that could mine actionable insights about drug development from clinical trial data, prescription sales, clinical tests, and genomic mapping. Although the team wasn’t able to turn this idea into a stand-alone functioning business, many of the tools and approaches that it developed were incorporated into the core business. Another example of this approach is a technology unit at AIG called Blackboard Insurance, run by Seraina Macia (whom we met in chapter 4 when she was CEO of the XL North American P&C business). Blackboard is a dedicated team, separate from mainstream AIG, focused on disrupting insurance underwriting by incorporating artificial intelligence and data algorithms into the process.

If a disruptive idea does emerge from a dedicated team, and if it can’t be developed further within the confines of the current business, then you can create a completely separate entity to bring it to market. The classic example is the way IBM developed its personal computer business in the 1980s (sold to Lenovo in 2005) by setting up a skunk works unit in a separate location with its own resources and without the inhibiting strictures and rules of the parent company that was at the time so beholden to selling mainframe computers. This kind of freedom allowed the IBM team to do whatever it needed to be successful, such as hiring and paying people differently, sourcing parts in new ways, creating new partnerships, and setting up separate sales channels. Another example was former CEO Jeff Immelt’s structure for GE’s software business, focused on the internet of things, which he created as a semiseparate entity located away from the core businesses—once again creating a culture more geared to high-tech innovation than the company’s standard industrial production.

In addition to setting up new, more independent entities, you also can spin off parts of your business as a way of separating the traditional core (with its sustaining innovations) from the more revolutionary areas that are more likely to create disruption. A recent example of this is Hewlett-Packard’s split into HP Inc. and HP Enterprise. HP Inc. focuses on the core printer business, which has lower margins and innovates incrementally. HP Enterprise, on the other hand, focuses on creating value for large corporate and governmental customers by developing new technology platforms and computing approaches. By separating into two firms, each could develop processes and prioritization rules more suited to the type of innovation needed. (Two years later, HP Enterprise doubled down on the strategy, dividing itself again by spinning off the lower-margin IT services included in the original partition.)

Even if you don’t go through a full process of disrupting your organization, engaging in a what-if thought exercise can be useful. For example, in 2001, Jack Welch issued a challenge to all of the GE businesses to “destroy your business.com.” The challenge of this iconic CEO was for each business—big and small—to actively consider how an unforeseen competitor, perhaps a startup in a garage, could compete and win against each established GE business. This was an eye-opener for many GE executives and leaders, who had become somewhat complacent in thinking that the only threats to their businesses would come from large competitors. As a result, many of them began to experiment with the disruptive ideas themselves—for example, the use of remote sensors for customer service, or mechanisms for self-service sales.

Corporate venturing and partnering

Another way to deal with potentially disruptive competitors is “don’t beat ’em, join ’em” (or have them join you). Many large companies, for example, have venture or acquisition teams that actively look for startups, path-breaking tech entrepreneurs, and university partners, and then invest in them, buy them, or partner with them as they develop their innovations and business models. We described how Thomson Reuters built these kinds of partnerships earlier in this chapter.

To make corporate venturing or acquisition work a source of future growth, leaders need to guide each investment so it prioritizes intelligence gathering and learning over immediate operating returns, though financial rewards may also accrue over time. Nike, for example, developed a venture-investing group that specifically looked for new technologies, startups, or small companies that were pioneering new approaches to sustainable (environmentally sound) manufacturing. When it found a company that was attractive, it made a small, minority investment that allowed it to have a seat on the board (or advisory group) and learn about the technology. Once the technology matured, so that it was worthy of incorporation into Nike’s manufacturing approach, it would either cut a licensing or partnership deal with the company or buy it outright. You might not be in a position to create a corporate venture investment group or make acquisitions, but you should always be looking for startups and new technologies that might have an impact on your business. And if you are leading a startup, you can identify corporate venture or acquisition groups that might be worth approaching too.

Lean innovation

A second approach to innovation that is important for building a sustainable enterprise is the “lean startup” model described in Steve Blank’s HBR article, “Why the Lean Start-Up Changes Everything,” which we first referenced in our discussion of strategy. While Christensen’s approach focuses on the outside threat of disruption, the lean approach focuses on the process for advancing, changing, or discarding innovative ideas: it is an approach for systematically testing and developing a new business model for a new feature, product, startup, or unit. It may be part of developing a new strategy, simply exploring and refining sources of potential innovation, or both.

The core of the approach is rapid experimentation with real customers. Blank observes that creating detailed theoretical business plans for a new venture is often a waste, since those plans usually reflect a number of untested and usually false assumptions about customer behavior and desires. It’s better to spend your time rigorously and quickly testing those assumptions. Do this by actually talking to potential customers—dozens of them—throughout the process of creating your new product or venture. As a result of these customer development dialogues, your people can then confirm the idea, pivot to a better idea, reconfigure it in some way, or drop it altogether. This means that nice and interesting innovation ideas or even sexy new technologies don’t end up wasting time and resources, but can “fail fast.” It also means that when you launch new enterprises, the chances of success are much higher, because you based them on confirmed principles. We saw this approach in the mortgage servicing innovation app at Thomson Reuters and in the exploration of the combined digital and broadcast approach in the development of the PBS KIDS 24/7 channel (discussed in chapter 2).

Leaders of teams and organizations are often the ones with the most outside view, but the lean methodology requires everyone in the process to connect to potential customers and their understanding of the product. It’s easy to sit around and congratulate everyone on their innovative ideas or vote among yourselves about which are most promising. Real innovation and sustaining value, however, derive only from customers that are willing to buy your product or utilize your service, and engaging them up front means that you know you are building something they are interested in.

For example, Avery Dennison, as part of its drive to create sustainable growth through innovation, launched several innovation teams as a pilot. Each team took an idea that had been developed within the company and then went out to potential customers to reshape it and make it more viable. The challenge to each team was to get some first sales results within 100 days, and to do that, they had to find real customers. One team, for example, took a foil product used in heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning applications and reconfigured it into an adhesive tape by talking with potential customers and then partnering with a major home improvement company. In so doing, it had the first sales in the prescribed 100 days and then expanded the product from there. Based on this and other pilots, Avery eventually launched dozens of teams, involving hundreds of people, and generated millions of dollars in new revenue—a tangible path toward shaping the future.

Encourage controlled failure

Whatever your approach to innovation, you and your organization must be willing to learn from failure. Failure is a necessary component of learning. If organizations don’t sometimes try things that are risky and have a higher than usual chance of failure, they can never create new forms of value. However, most organizations (and, in fact, most people) avoid taking on risk because they don’t want to fail or suffer the public shame of doing so. We’ve all been taught that failure is bad. And it certainly can have career consequences or financial implications. But as you build your innovation process, you must build it in such a way that it allows failures to happen, in controlled ways, and to leverage what those failures can teach you.

As an example, one of Thomson Reuters’s innovation champions, Bob Schukai, was an early tester of Google Glass (a device developed to display hands-free information on the lenses). Schukai and his team developed an application that would allow law enforcement officers to rapidly access information on their glasses at traffic stops. When Google stopped its Glass project, the application died with it. But its development had helped Thomson Reuters better understand information needs in the public sector, gain familiarity with public databases, and address privacy and safety concerns that it could use in various other projects. As innovation leader Manuel reflects, “The Google Glass project may not have ended with a multimillion-dollar revenue stream for us, but it sent a powerful message to all of our employees that innovation is alive and well.”

To encourage failure in a controlled way, find opportunities for lean testing of initiatives like those described, in which concepts and assumptions are tested incrementally and thus with less risk. We’ve also seen this in action in the results practice we described in chapter 4, in the rapid experimentation exercises Seraina Macia led to get her team to reach the high goals she had set. Other experiments can be even more lightweight—in a “painted door” test, for example, a company advertises a product on the web to measure customer interest before it actually builds it. Interested users who click on the image get a message asking for their email so they can be notified when the product is ready or if they want to participate in further product testing. But if clicks on the ad are low, then the company doesn’t invest further, which saves time and money, and the failure then frees up space for testing the next new idea quickly and frugally. Intuit uses this approach frequently as a way of quickly learning whether a new product or feature will have traction with customers or not.

Another way to encourage risk taking, failure, and learning is to set up a separate unit for developing a new business, product, or service, similar to what we discussed as part of disruptive innovation. In his HBR article “Planned Opportunism,” Vijay Govindarajan stresses that this kind of “new-co” operates with a different set of metrics and expectations so that it can operate more freely and not have to hit the targets that would ordinarily apply and might stifle risk taking in the “core-co.” He describes IBM’s use of “emerging business opportunity” units that can test embryonic business ideas without the usual requirements to return capital, achieve revenues, and so on. This doesn’t mean that the teams in these units don’t have goals, but that the goals are more appropriate to a nascent idea than to an established business. You can also set up an incubator within your company to serve this function.

How to learn from failure

Processes for encouraging failure are one thing; learning from it is another. In their HBR article “Increase Your Return on Failure,” Julian Birkinshaw and Martine Haas suggest three steps to make sure that you use your mistakes to grow: learn from every failure, share the lessons, and identify patterns. The after-action review (AAR) process originally developed in the military is a structured and systematic way of doing this. In their HBR article “Learning in the Thick of It,” Marilyn Darling, Charles Parry, and Joseph Moore explain that AAR consists of a series of meetings and discussions with participants in a project or innovation team to assess what worked or what did not, what assumptions were used, and what should be done differently to improve either the current project or the next one. The outcome is not just a report, but also provides specific lessons linked to future actions, with clear accountability assigned for putting them into practice.

As an example, many years ago one of us worked with Johnson & Johnson’s business development leaders to assess their process for integrating acquisitions, which was a key strategy for growth and innovation. After interviews with managers from a number of companies that had been brought into J&J (with varying degrees of success), several lessons emerged, such as the need for a full-time integration manager to be part of every acquisition, and for corporate functions to limit the number of requirements they placed on new acquisitions. These lessons and others were discussed with the CEO and his leadership team and then applied to the next large acquisition. Based on the after-action experience of that integration, the learnings were further adjusted so that J&J became increasingly skillful at integrating acquisitions.

Building a future-focused culture

Setting up a process and structure for innovation in your unit or team is one thing. But the process can never succeed if you don’t also build a culture to match. An innovative culture is one in which your employees are (and you encourage them to be) intellectually curious, open to change, resilient, and flexible. It means that they actively learn new ways of working (and learning from failure). It means they are future oriented, thinking for the long term. And it means that they have an appreciation and capability for innovation itself.

These qualities are imperative for innovation because they enable managers and staff in the organization to embrace the future rather than resist it. But there is an added benefit. What happens when you’re no longer leading that organization and can’t personally steer it into the future? Building a culture centered around continuous innovation means that the organization is set up to succeed long after you are gone. Leaders after you will inherit an institutional capability and have a strong foundation upon which they can build. Research by McKinsey’s Dom Barton and others suggests that when leaders build this kind of long-term thinking into the way the company does business, it creates significantly greater financial return, market capitalization, and job creation over the long term—and not by a little, but by a lot (see the HBR article by Barton and others, “The Data: Where Long-Termism Pays Off”).

As we saw in chapter 3, shifting your organization’s culture is not easy and depends on building the right leadership team, facilitating the right team interactions throughout the organization, giving tough feedback, fostering learning and development, and creating the right incentives. Let’s examine what that looks like from an innovation perspective.

Developing a learning capability

The ability to learn rapidly is a critical capability for any organization committed to innovation. You can hire for this skill, but you also must develop your existing talent and put in place structures and mechanisms to foster the capability throughout.

As part of Thomson Reuter’s transformation, Smith and his human resource team emphasized recruiting staff with technological, entrepreneurial, and problem-solving skills, and spent extra time coaching them to be successful in the emerging transformation. But he and his senior executives also coached other rising leaders in the organization who showed interest and ability to help reinvent the company, such as the innovation champions and the corporate innovation team. Smith made sure that individuals who showed interest and skill in innovation were involved in workshops, hackathons, and projects throughout the transformation process and would deliberately seed them in different initiatives across the organization. Leadership programs in the company also were aligned with the emerging future direction. And as the transformation advanced, Smith also made sure that human resources and performance management systems were updated and aligned with changes in the business. Smith’s creation of the technology center in Toronto, which allows engineers and developers who are working on common topics, like artificial intelligence, to be co-located, was another way that Smith and his team strengthened the learning capability.

Boeing gives us another example of what it takes to build a culture of innovation. Before Jim McNerney retired as Boeing CEO in 2015, he realized that the company’s continued success demanded that its people and partners approach problem solving and product development in new and different ways. McNerney worked with his successor Dennis Muilenburg, who became president in 2013, CEO in 2015, and chairman of the board in 2016, to identify the internal capabilities Boeing needed to compete and win in its second century. (The company began operating in 1916.)

To foster this new capability, senior business leader Pat Dolan was appointed to work with the businesses and with Human Resources to teach managers and engineers how to differentiate between incremental change and step-function change, and how to handle the latter more effectively. Dolan explained to us that for incremental changes, the company had plenty of subject matter experts who could develop solutions. But for challenges that hadn’t been faced before, they didn’t necessarily know how to approach them—there were no detailed plans to execute. “Instead,” Dolan said, “we need to empower people to learn as fast as possible so that they can be successful. The key is not fast execution, but fast learning.”

To develop his organization’s learning skills, Dolan and his colleagues brought teams of Boeing people together for multiday workshops to tackle real, intractable problems that required substantial change. The outcome of each of these sessions was a “learning plan,” rather than a detailed plan of what would be done. Dolan explained: “We keep it at a high level so they don’t get lost in details too early. They have to figure out the path that they are going down first and not lock in too quickly.” Once they had this learning plan, the teams were asked to return to their businesses—working with other functions, suppliers, and partners—and actually make progress against the problem. They then came back for another workshop several months later to reflect on what they accomplished and learned, and how they approached the problem differently.

Dolan believes that this process represents at least a four-year journey toward developing new capabilities and strengthening the company’s culture. After all, the previous culture took 100 years to create. After several years, Dolan and his team have sponsored approximately forty of these workshops with an average of fifty people at each one—and with continued reinforcement from senior company leadership. As a result, nearly 2,000 key managers and engineers have begun learning how to address problems differently and with more flexibility, skills needed to help Boeing develop and inspire its people, innovate more quickly, and further grow its business.

Incentivizing innovation

In order for innovation to take root and become part of the culture, people on your team or in your organization have to feel that you will reward and recognize the pursuit and development of new ideas, and not dismiss or punish them. Doing this is more difficult than it might seem. For most ongoing enterprises, no matter whether large or small or for profit or nonprofit, incentives are inevitably weighted toward maintaining, servicing, and incrementally growing the current business. After all, you don’t want people to sit around and daydream and doodle when there’s work to be done. Some companies (e.g., 3M and Google) famously encourage employees to spend a certain percentage of their time working on speculative and innovative projects. But these are the exceptions. Most companies focus their people on what needs to get done today, while leaving innovation for the future to the R&D group or a few senior executives.

As part of the TIAA transformation, Ferguson knew that new ideas and innovation had to come from many parts of the company, not just from him. He encouraged new business exploration more widely with the creation of growth teams comprising people from different functions, tasking them with explicit objectives to pursue and develop new ideas. Ferguson also actively promoted people who exhibited the spirit of innovation, and he made a point of knocking down potential procedural and process blockers that were getting in the way of new ideas. Ferguson also communicated constantly about the firm’s transformation and publicly recognized people who were at the forefront of TIAA’s reinvention.

Thomson Reuters’ Catalyst Fund exemplifies another kind of incentive mechanism that goes beyond just the promised seed money. Employees at all levels were energized not just by the cash, but by the promise of improving the business itself. Indeed, the internal publicity about the initial winners and the overall process triggered a steady flow of applications. Over four years, nearly 100 ideas were funded, many of which have been put in the market and have given the overall fund a very healthy return on investment.

In addition, many of Thomson Reuters’s innovation initiatives have helped make organic innovation part of the culture. Driven by an executive sponsor and a full-time innovation leader, these have included:

- Building innovation metrics such as number of ideas in each stage of the innovation pipeline, the overall participation level of employees by rank and location, and survey results on employees’ sense that they can be innovative and receive recognition for their efforts

- Appointing “innovation champions” in every business. Each businesses and corporate function designated a senior high-potential manager to help implement programs and processes to achieve the new goals and metrics. In addition, the champions created a common terminology for and built an online Thomson Reuters network filled with resources that employees could use to educate themselves about the concepts and practices of innovation

- Orchestrating a communications campaign with blogs, articles, and video interviews with internal innovators and other employees’ views on innovation

- Organizing enterprise innovation workshops, with representatives from all parts of the business, to identify and plan efforts that would drive new or existing products or process solutions across the company’s platforms

- Launching an “operational innovation fund,” similar to the Catalyst Fund, to encourage more creative back-end software development for operations centers

- Establishing Innovation Challenges to crowdsource solutions plaguing an area of the business or a customer group

- Supporting the innovation lab network, housed within the Technology organization, but leveraged across the entire company to consider emerging technologies and the art-of-the-possible to build solutions for the future

All these steps, directed by a senior-level innovation steering committee, were initiated as experiments to focus on learning, adjusting, and figuring out what would work over time and then were iteratively improved. For example, the innovation metrics were sharpened as the definitions of innovation evolved, and the experience of the first few innovation champions helped clarify criteria for selecting additional ones. Also, all these steps were carried out with as much transparency as possible, so that all Thomson Reuters employees not only would know what was happening, but could themselves contribute to the efforts along the way. In describing Thomson Reuters’s goals, Katherine Manuel reflects: “Much of what we did was to democratize ideation and rapid experimentation and communicate successes and failures. Our aim was to create as many opportunities for employees, no matter what level they are, which business they reside in, or where across the globe they sit, to participate. We wanted all employees to associate making changes to improve what they do and how they do it as innovation: this is where innovation at scale can fundamentally shift the performance of a large organization.”

As a result of all this work, after just a few years, organic growth through innovation has become well established as the norm at Thomson Reuters. The innovation network is one of the most visited sites on the company’s intranet. Employees submit hundreds of ideas for consideration at the enterprise innovation workshops and challenges. Catalyst Fund projects are regularly prototyped, piloted, and then rolled out to customers. And the businesses have a robust portfolio of pioneering new ideas that are moving through their pipelines. So although there is still much to be done, and the jury is still out, clearly the company now has incentives in place to sustain an ongoing innovation culture.

Modeling innovative thinking

Your behavior as a leader sends strong signals about the kind of culture you are trying to create (as we discussed in chapter 3). Thus, to build innovation into your unit’s or company’s DNA, you and your leadership colleagues must personally demonstrate and exemplify it all the time. Ferguson at TIAA provides an illustrative case: throughout the corporate transformation of the business, this CEO did his best to model the behavior suited to future-seeking growth: displaying curiosity and excitement about new ideas while still respecting the importance of day-to-day business, showing genuine concern for others in his personal exchanges across the enterprise to build trust for learning, and serving on nonprofit boards, both to demonstrate his commitment to the values of service while also developing insights about the future from other organizations. He also encouraged his other senior leaders to do the same.

Similarly at Boeing, CEO Dennis Muilenburg regularly participates in candid, problem-solving dialogues with innovation workshop participants at the company’s learning center in St. Louis, Missouri, and tries to think along with them as they tackle difficult business challenges. Muilenburg also insists that each innovation workshop team has a senior sponsor from the executive ranks who can challenge the team to think creatively and come up with innovative solutions. Their participation makes it clear to team members and others who hear about the teams that innovation is important for everyone.

The same is true at Thomson Reuters. At Catalyst Fund meetings, the company’s leaders ask tough questions, encourage risk taking, and display the openness needed to foster creative thinking. In doing so, these senior executives model the importance of commercialization, signaling that “cool ideas” aren’t embraced for their own sake, but must actually solve customer problems. While encouraging creative thinking, they still remind people at all levels that innovation is ultimately a means for delighting customers and growing the enterprise.

Sustainability is up to you

There is no magic formula for continuous reinvention and ensuring that your unit or company will be sustained for the long term. The innovator’s dilemma is still alive and well and is not easy to overcome. But if you get ready for the future, manage a portfolio of innovation projects that helps shape the future, and embrace a culture that supports adaptability and change, you’ll dramatically increase your chances of enduring success.

Wherever you sit in an organization, or whatever kind of organization you work in, adding future thinking and discovery to your job is also a stepping-stone for longer-term success. It will doubtless take you out of your comfort zone—there’s nothing easier than simply focusing on tomorrow’s deadlines—but it’s a discomfort every great leader has learned to embrace.

Questions to Consider

- Balancing your own time. How much time do you spend focusing on getting things done today versus planning for the future? If your time is overly skewed toward the present, how can you create capacity for developing longer-term opportunities?

- Scanning the environment. What do you do to identify and keep track of potential threats and opportunities for your team, both inside and outside your organization?

- Solidifying the core and building surplus. Is your key existing business well managed? Is it creating some extra headroom to explore and pursue future-seeking opportunities?

- Innovation portfolio. Do you have a portfolio of innovative experiments—with different time frames and risk profiles—that can help you and your team shape the future?

- Freeing up time for innovation. Which of your team’s activities can you divest or stop that will give you more time and resources for innovation?

- Building capability to innovate. Do your team members understand different types of innovation such as incremental adjacencies and disruptive and lean innovation? How can you educate them on these different approaches and give them opportunities to learn them through experience?

- Failure and learning. To what extent is it all right for people on your team to take risks and fail? What can you do to encourage the right kind of controlled risk taking and deliberate learning?

- Culture for innovation. What can you do to motivate your team members, individually and collectively, to continually look for new and better ways to conduct your business or contribute to your organization and customers? Can you give them time or seed money to shape new ideas? How well do you model a culture of innovation?