![]()

1.

Building a Unifying Vision

A leader’s role is to raise people’s aspirations for what they can become and to release their energies so they will try to get there.

—David Gergen

Exceptional organizations have an exciting, clear, and simple vision—a vision that honors and reinforces the core purpose of the organization, but also creates a picture of where the organization is heading and what it aspires to accomplish in the future. Consider, for example, DuPont’s vision, “to be the world’s most dynamic science company, creating sustainable solutions essential to a better, safer, healthier life for people everywhere”; or Facebook’s, “to give people the power to share and make the world more open and connected.” Divisions and teams within organizations also have visions; for example, Nest, the smart-home division of Alphabet (the parent of what was originally Google), has a vision of creating “the thoughtful home: A home that takes care of the people inside it and the world around it.”

The practice of crafting a vision is a key component of your ability to create significant impact as a leader. Whether you are in charge of the whole organization or just a piece of it, a vision provides the starting point for developing strategic plans, recruiting talent, setting goals, and challenging people to find new and better ways to get things done. Equally important, the vision helps to align groups and individuals (who may be doing quite different work) around a common direction, while also inspiring them to contribute to something that is bigger than them.

Your role as a leader is to shape a compelling vision to fit your organization (or unit, or team) and its environment, and then recraft it periodically as conditions change. By crafting, sharpening, or revising your vision in the right way, at the right time, you can have enormous influence over your organization’s or unit’s direction and the emotional engagement of your people. But this kind of vision doesn’t just drop out of the sky. The practice of making a vision is challenging because:

- It can be hard to determine whether it’s the right time to develop a new vision; you don’t want to do it too often and risk burnout, or not often enough and risk complacency.

- It’s easy to be too timid in setting a vision; to do its job, a vision must be bold.

- Many of your colleagues and constituents will have competing ideas and points of view and you’ll need to corral these into a coherent direction.

- The process can be time-consuming, so you’ll have to carve out time to focus on creating the vision while dealing with shorter-term issues that will seem more urgent and compelling.

- Assuming you are not the CEO, you’ll need to connect the vision for your specific team or business unit to your company’s overall vision, without losing the overall energy and meaning of the broader vision. Sometimes this is just a smaller version of the corporate vision, but it can be supportive while somewhat different.

Tackling these challenges head-on is a critical part of stepping up from management to leadership. And although it doesn’t have to be the first thing you do, you will have to focus on building a unifying vision periodically because it provides the foundation for many of the other practices that will make you a great leader. If you practice it on a relatively small scale with your team or your department, it will give you more confidence to build a broader vision at another point in your career.

As part of this practice, leaders need to first understand what a good vision is; they then need to lead a process for determining the vision for their organization or unit. To give you a sense of what this means, let’s look at how Jim Wolfensohn shaped a new vision for the World Bank as a whole and how other leaders in the Bank then built exciting visions for their own teams as a result.

Creating a vision for the World Bank

When Wolfensohn became president of the World Bank in 1995, he inherited a venerable institution under siege. The organization had been successful in supporting worldwide economic development after World War II and promoting democratic social and economic systems during the Cold War. But with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, suddenly the West had won and the quasi-political purpose of the World Bank no longer made sense. Additionally, the opening of world financial markets and the rise of China and other Asian economies meant that developing countries had access to capital from sources other than the World Bank. Meanwhile, the Bank was being criticized for earlier neglect of such concerns as the environment, local culture, corruption, social justice, and others. By the time Wolfensohn took the helm, these forces had coalesced into a public movement, called “fifty years is enough,” that explicitly questioned the World Bank’s need to exist.

These attacks caused internal morale to plummet. In addition, an internal Bank study had just concluded that one-third of the Bank’s projects were not producing the desired economic results.

Given this crisis of confidence, Wolfensohn realized that he needed to reestablish a compelling vision that would support the continuation of the Bank and reenergize the staff. “Reconstruction” and “strengthening the Western Bloc” were no longer relevant, and the core purpose of broad “economic development,” while still important, was too vague to resonate with staff at a personal level or the outside world. Something else was needed.

Based on active discussions and debates with his senior staff, Wolfensohn decided that the answer was to refocus the Bank on poverty reduction, an area that an earlier president, Robert McNamara, had first emphasized, but that had become overshadowed by years of debt crises, structural readjustments, and other development issues. After all, in 1996 poverty was endemic, with more than 28 percent of the world’s population living in extreme poverty (less than $1.90 per day, according to the World Bank’s data). Remedying that dismal reality was an urgent need.

Wolfensohn realized that he couldn’t simply cook up a vision for the Bank with his senior team and then drop it on everyone. Instead, there had to be a process of dialogue with stakeholders—listening and testing in a way that would make them feel that the vision was something that they had helped create. To do this, he asked Caroline Anstey, his head of communications, to draft an initial vision statement that would capture his intent to focus the Bank on poverty reduction and then to engage multiple stakeholders in fleshing it out. The team used the initial draft to solicit input from clients, government officials, board members, and senior managers. It held focus groups with staff and built group discussions into various meetings, off-sites, and leadership events. Wolfensohn himself actively participated in many of the sessions and regularly reviewed the emerging vision with Anstey and others.

The result was a phrase that was eventually chiseled in stone on the walls of the Bank’s headquarters building in Washington, DC: “Our dream is a world free of poverty.”

The stakeholder discussions also generated many other messages about the organization’s aspirations, so that the overall vision eventually looked like this:

Our dream is a world free of poverty.

- To fight poverty with passion and professionalism for lasting results

- To help people help themselves and their environment by providing resources, sharing knowledge, building capacity, and forging partnerships in the public and private sectors

- To be an excellent institution able to attract, excite and nurture diverse and committed staff with exceptional skills who know how to listen and learn

Over time, with regular repetition and use, this statement and the aspiration it described became an antidote to the external criticism that called for the end of the Bank. It also helped leaders in the organization to focus and prioritize the Bank’s strategic goals, both at the corporate level and throughout the regions, countries, and technical networks in which it operated. Indeed, the focus on poverty alleviation eventually became an ongoing measure of progress, not only for the Bank, but also for other development institutions such as the United Nations. The vision also resonated with the staff at a personal level since many Bank staff either came from poor countries or frequently traveled to areas that were economically disadvantaged.

The power of the World Bank’s vision was not just a matter of framing strategy and building engagement, however. It also was unifying, allowing the Bank to leverage the contributions of its individual employees at scale. The Bank, like most organizations, consists of people with a wide variety of skills and backgrounds across many functions. There are economists, agronomists, water experts, civil engineers, accountants, clerical personnel, writers, administrative assistants, and many more, all in different silos, departments, and locations. But because the organization’s “world free of poverty” vision was so powerful, these individuals with their unique contributions could feel as if they were joining forces to achieve that larger inspirational goal together. They weren’t just writing reports, doing studies, or making loans, but were part of an institution and a team that were striving to make life better for millions of people.

This vision also cascaded through the organization. Leaders of regional divisions and functional areas throughout the World Bank developed visions that catalyzed their people around particular challenges relating to poverty elimination. For example, Mieko Nishimizu, the vice president of the South Asia region, focused on a vision for reducing poverty at the village level in her countries, particularly since many of the previous economic development projects had not reached the villages. Dennis Whittle, another senior leader who headed up a strategy team, developed a vision of leveraging ideas worldwide to fight poverty rather than just relying on the Bank’s expertise. This led his team to create a global “development marketplace” for poverty-reduction solutions that eventually became a regular part of the Bank’s strategic approach.

What is a vision?

Before we describe how you as a leader create a vision for your department, team, or unit, we need to explain what a vision really is—and what features make it work in all the ways that the poverty-elimination vision Wolfensohn helped engender worked for the World Bank.

“Vision” often means different things to different people; in organizations, it’s often confused with “mission,” “values,” and more. These concepts overlap somewhat, but we believe that vision gives you a unique opportunity to exert your leadership. It is the one pillar that you, as a leader, can periodically reassess and reshape, as Wolfensohn did at the World Bank. Nobody else can do this for you; it’s your role to catalyze and steer both the process of determining a vision and also the particular boldness of your approach.

So how is a vision different from a mission or a company’s values? An organization’s mission is its long-term, mostly unchanging charter—its unique reason for existence. For the World Bank, the mission is to provide financial and technical support for economic development in disadvantaged parts of the world. A network of hospitals might have the mission of “providing a full range of health-care services to a target market,” or a manufacturing concern in business might be “to develop, produce, sell, and service certain products for small and medium-sized enterprises.” These kinds of statements define the business they are in and can be accessed in their legal articles of incorporation, founder’s early statements, or discussions with board members and senior leaders.

Values too are enduring, though they may respond a bit to the times. These are the ground rules for how the enterprise and its people should work to get things done. Values tend to be more personal; they are the ideal operating guidelines for personal behavior that individuals are supposed to follow as they do their work. At the World Bank, for example, a code of conduct called “living the values” outlines specific ways that staff should interact with colleagues, clients, civil society, and local communities, and how managers should ideally behave toward their people.

A vision, on the other hand, is a picture or snapshot of what the organization or your unit wants to accomplish over the next several years or where its efforts are pointing it in the long term. The vision conveys a direction—not how to get there (that’s strategy), nor the immediate measurable goals that drive performance, but a context within which specific strategies and goals can be framed. For the World Bank, the shift to freeing the world from poverty represented a material change from the organization’s previous direction of facilitating post–World War II reconstruction and supporting Cold War–era democratic capitalism. And at the unit level, Dennis Whittle’s vision to leverage ideas from around the world that could reduce poverty was a dramatic change from the strategy team’s previous reliance on its own experts. (Table 1-1 shows how vision is different from mission and values.)

To be sure, different leaders approach the term “vision” differently. See the box “The elements of a vision” for another classic definition of how these ideas fit together and what makes an effective vision.

The elements of a vision

In their classic HBR article “Building Your Company’s Vision,” Jim Collins and Jerry Porras suggest that your enduring mission and your aspiration are the two elements that meld together to form your vision. Based on their research about organizations that are “built to last,” they say,

A well-conceived vision consists of two major components: core ideology and envisioned future . . . Core ideology, the yin in our scheme, defines what we stand for and why we exist. Yin is unchanging and complements yang, the envisioned future. The envisioned future is what we aspire to become, to achieve, to create—something that will require significant change and progress to attain.

Putting these two elements together, they explain, requires that you “understand the difference between what should never change and what should be open for change, between what is genuinely sacred and what is not.”

At the World Bank, for example, supporting economic development through loans and technical advice is the unchanging yin that says why the institution exists, while “a world free of poverty” is the yang, the envisioned future.

What makes a vision compelling?

It’s not enough just to set a direction. A vision has to have certain characteristics to be an effective motivator and strategic unifier.

A good vision is aspirational, almost dreamlike, simple, and compelling. It’s the kind of statement that should make you want to be part of the organization, to join in the pursuit of that vision. It has emotional resonance. The vision also must be clear: if it’s confusing or vague, nobody will follow it. Finally, it must be bold: you must push your organization to look to the future, see around corners, and point toward something audaciously far in front of it.

See the box “Criteria for organizational vision” for a checklist of these criteria to use as you work on your vision.

Criteria for organizational vision

- Conveys a picture of the future

- Bold

- Simple and clear

- Emotionally compelling

- Aspirational

- Provides context for strategic planning

Other vision examples

For the formal vision statements of a range of other real companies, see table 1–2.

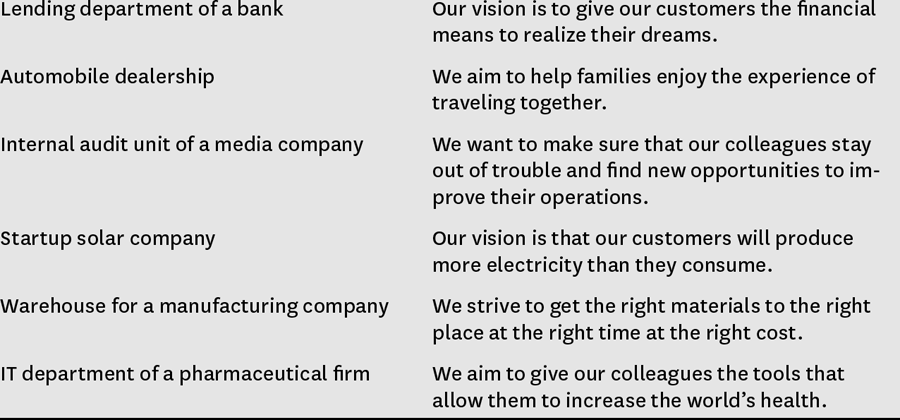

But not every leader has the opportunity to create a vision as far-reaching as those of these large corporations. The vision you create for your unit, however, should still be powerful for you and your team and should make all of you feel that what you are doing is more than just a job. So no matter what kind of organization you are a part of, think about how your team or unit can have a transformative (or extremely positive) impact on your internal or external customers. (See table 1–3 for some examples.)

The World Bank’s vision of “a world free of poverty” has all of those characteristics. It’s simple, compelling, and highly aspirational, and it allows the Bank’s leaders to set strategic goals, subgoals, and priorities for projects, regions, countries, and the institution as a whole. See the box “Other vision examples” for more visions at both organizational and unit levels.

Boldness

Vision isn’t about just doing incrementally more than what you do now. Rather it’s about defining a direction that is significantly different to create new value for the organization and its constituents—not tomorrow but over many years. As Dominic Barton, the global managing partner of McKinsey, told us, “Managers take care of the railroad tracks that are already there and make sure that the trains run well. But leaders shift the tracks, they ponder different futures, they swing for the fences.”

This boldness is important because it is what inspires, what serves as a North Star for people throughout your organization. Jim Collins and Jerry Porras describe what they call BHAGs, or “big, hairy, audacious goals”:

All companies have goals. But there is a difference between merely having a goal and becoming committed to a huge, daunting challenge—such as climbing Mount Everest. A true BHAG is clear and compelling, serves as a unifying focal point of effort, and acts as a catalyst for team spirit. It has a clear finish line, so the organization can know when it has achieved the goal; people like to shoot for finish lines. A BHAG engages people—it reaches out and grabs them. It is tangible, energizing, highly focused. People get it right away; it takes little or no explanation.

Consider the vision of the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas. Its vision is “to make cancer history,” which has the double meaning of developing breakthrough science (historical new discoveries) and eradicating cancer altogether. It resonates with researchers, clinicians, and ancillary workers, as well as donors, patients, and family members. It’s also memorable and vivid—and certainly bold. Its boldness has spawned more than a dozen specific moon-shot programs in different clinical departments to make significant advances in reducing mortality and suffering on specific types of cancers in defined periods of time.

Of course, your team may not have a vision at the scale of eradicating cancer or eliminating global poverty, but to be effective, a vision must still be significant relative to the day-to-day work of the team. At AIG, for instance, Seraina Macia currently runs a unit called Blackboard Insurance that is seeking to improve commercial underwriting by developing artificial intelligence and data analytics to reshape the whole process and, by extent, the industry itself. Similarly, the human resource team of a large corporation that we know formulated its vision around making the company one of the top five places to work in the United States and a preferred destination for graduates of engineering schools.

For the most compelling visions, going bold doesn’t mean financial success, but rather striving for an exciting contribution to customers or to society. In the HBR article “Successful Startups Don’t Make Money Their Primary Mission,” describing successful new ventures, Kevin Laws, COO of AngelList, argues that if the goal of an organization is simply to make money, it won’t make it through the rough patches. Sure, it needs to make money in order to achieve its vision, but without that separate vision to guide and inspire the people involved, the organization won’t do either. Examples of this abound: Google didn’t set out to become a company with one of the largest market capitalizations in the world, but rather to “organize the world’s information and make it accessible to everyone.” Apple didn’t start out with the vision of having an astronomic stock price, but rather, in Steve Jobs’s original formulation, to “make a contribution to the world by making tools for the mind that advance humankind.”

The vision cascade

Note that visions and associated BHAGs are not the sole province of the CEO and the corporate level. Like Macia, if you are the leader of a unit, division, or even a team, you can develop your own bold vision. But for that kind of vision, there is an additional criterion: it must support and align with the organization’s overall vision.

For example, Macia’s Blackboard unit at AIG is focused on underwriting, but it aligns with and supports the overall vision of the company to leverage technology and data science in the reinvention of insurance. Similarly, the MD Anderson moon-shot programs are essentially visions created by clinical division heads, but they all support the overall vision of “making cancer history.”

Whether you are creating a vision for your whole organization or recrafting a vision for your particular unit, keep these definitions and requirements in mind. They’ll help you refine and improve your vision—and help your team do the same—throughout the process.

Crafting your vision

You can break the practice of actually crafting a vision to meet these standards into four sequential steps. The first is to determine whether it’s even the right time to create or revise your organization’s or team’s vision. The second is to establish your own draft vision as a starting point. The next step is to engage your own team and other stakeholders in actually crafting a more refined vision together. Finally, you’ll need to help your people connect their work to the vision so that they understand how their contribution makes a difference.

Step 1. Determine whether the time is right

Whether you are a CEO or the leader of a department, function, or plant, you need to periodically ask yourself whether you have the right vision for your organization and whether it’s time to modify it or work on a new one. That’s all the more necessary if you’re just coming into a new leader ship role.

But, often, particularly for new leaders, there is so much going on and so much to do, it’s easy to get caught up in the day-to-day activities and forget or put off setting direction.

Even long-serving executives can become too passive; having been in the same organization for a while often makes leaders blind to their changing environment—at least until some crisis shakes their world and sinks their numbers. But staying attuned to the ways the world is changing is critical for a leader. It is your opportunity—and your role as a leader—to identify when to reshape a vision.

When to develop a new vision

It may be obvious that you need to sharpen or reshape your vision completely because of a changing environment or new organizational opportunities, as was the case with the World Bank. Or it may simply be clear that the current path isn’t working.

But the need for a new vision may not be immediately obvious. For example, when Patrick O’Sullivan became the CEO of Eagle Star Insurance in the United Kingdom, the company’s senior leaders told him that the company was doing fine and that its vision to provide reliable, low-cost property and casualty insurance was sufficient. When O’Sullivan dug into the numbers, however, he realized that the current business model wasn’t working and that Eagle Star was surviving only because it was understating its reserves and was covered from market pressures by its parent company, British American Tobacco. As a result, O’Sullivan spent his first few months meeting with his direct reports, other managers, and groups of employees to help them appreciate the so-called burning platform. As people began to realize the gravity of the business situation, he was able to discuss with them a fresh vision for the company around the concept of “winning through customer service.” Eventually this led to a major turnaround of Eagle Star and its subsequent sale to Zurich Financial Services.

Another trap to avoid is what Collins and Porras call the “we’ve arrived syndrome.” This is when your unit or team has had a spectacular achievement—you’ve really accomplished your aspirational goal, but you haven’t replaced it with something new. The temptation for the team (and for you) in this situation can be to look backward at how exciting things were rather than looking forward. If you’re not careful, a sense of complacency can set in, and you miss the next threat or the next competitor on the horizon. Overcoming this syndrome requires the development of a next new challenge, a new vision and aspiration.

For example, Intuit spent twenty years achieving the vision of changing the way people managed their personal finances and, in the process, became a software powerhouse, with Quicken as its flagship product. Once it got to the summit, however, other companies started to copy its success, moving into the market and finding new ways of attracting customers. When Brad Smith became CEO in 2008, he recognized that the company had become so focused on adding incremental features to improve usability that it had no big aspiration for the future. So he worked with his team to develop a new vision of becoming “one of the most design-driven companies in the world,” moving the organization toward thinking about delighting customers. This new vision led Intuit to design products differently, incorporate new skills, sell off legacy products (including Quicken), and rethink many of its ways of working.

Finding the capacity to do this isn’t easy, particularly since most leaders already are starved for time. Carving out additional time to devote to vision is hard and can easily be put off until later. So set aside a particular time each year to reflect on your vision and think about whether it still fulfills its purpose. For example, Gary Wendt, the former CEO of GE Capital, used to ask all his business leaders to conduct “dreaming sessions” with their teams each year in advance of the strategic planning process. Each team had the opportunity (and the luxury) of stepping back and dreaming about where the business could be in a few years and how it could be significantly different and better, which would then force the team to assess whether the current vision would get it there.

When to stay the course

Don’t be too fast to reset your organization’s path. Many visions will last for years and don’t need to be changed significantly. The amount of time and work it takes to create a vision is significant—and can actually be destructive if you are pivoting too quickly—so it might be that all you need to do is make sure that everyone understands it.

If you do want to retain the existing vision, at least for now, convey your decision to your team and the organization. Often, new leaders feel that they have to make a big splash and reshape their unit’s or company’s vision right away, or others may expect them to do so. But since the vision is an aspiration that requires years to achieve, it is perfectly legitimate to say that it’s still the right direction but “we’re not there yet.” Then you can focus your energy—and everyone else’s—on what’s needed to keep moving forward, pick up the pace, or go about achieving the vision in some new ways. The key is to be explicit about your decision and not leave people guessing or wondering when the big announcement will come.

Finally, even if you and your team are convinced that you need new vision, that might not be the first thing you do as a new leader. Sometimes there are more urgent issues to tackle, particularly relating to the survival or stabilization of the firm. Louis Gerstner, the former CEO of IBM who took over the company in the early 1990s when it was experiencing a major financial crisis, is famously misquoted for saying, “The last thing IBM needs is a vision.” This was considered a startling comment from a prominent senior leader who had previously been a consultant at McKinsey and was famous for his visionary and strategic acumen. What he really said was that “the last thing IBM needs right now is a vision.” Gerstner helped IBM refashion its vision as a hardware provider to a provider of integrated solutions. But he started that process in his second year after first dealing with cash flow problems, getting the right leadership team, and redesigning the structure of the company at the beginning of his tenure.

How to gauge whether you need a new vision

To understand whether your organization needs a new vision, first assess the current vision. Is there one? Does it meet the criteria laid out for a good vision earlier in this chapter? (See table 1–4, “Is it time to create or refine your company’s vision?” for more questions to ask.)

If you are interviewing for a new leadership role, you should ask each person you talk with to describe the vision, not just for the company, but also for the unit that you might be leading. That’s a quick way for you to learn whether one really exists or whether you need to change it. In some cases, it will be obvious, because of either performance shortfalls or a crisis—and that may be why you are being hired. In other cases, however, you may see the need for a new vision, but others may not.

Even if you’re not new to your organization or position, you should periodically test whether everyone truly understands the vision by talking to a random sample of people in your organization or department—say, fifteen to twenty. Ask each to quickly share their view of where they think the organization is heading over the next few years and how they feel about it. If you get many different answers or the answers aren’t convincing, then perhaps it’s time to get to work on a new or refreshed vision. You should also periodically ask yourself and your team whether there have been significant changes in the business environment, technology, or competition that should trigger a rethinking of the vision.

Step 2. Develop your starting-point vision

Once you determine that it is time for a new or revised vision, you need to put together a draft starting point to set the process in motion and to convey your perspective on what to include. This doesn’t mean that you need to be the sole visionary for your company or your part of it, but at the same time, you can’t be absent from the process and just give your vision team a blank sheet of paper.

Based on extensive surveys of thousands of working people in organizations, professors James Kouzes and Barry Posner, in their HBR article “To Lead, Create a Shared Vision” have found that the ability to be forward looking is the second-highest characteristic of what employees look for in a leader (trailing only behind honesty). In other words, your followers—the people you lead—are expecting you to envision, anticipate, and set a direction for the future. Depending on where you are in the organization, this can mean different things. At lower levels, it could center around articulating a new way of getting projects done faster and with greater impact, or significantly ratcheting up service to customers; at higher levels, it might involve setting direction for how your unit will make a difference in the next few years; and at the CEO level, the challenge will be to figure out an exciting enterprise path for the next decade.

To do this, Kouzes and Posner strongly suggest that you start by talking to and listening to your own people, both direct reports and other followers. Find out their ideas, dreams, thoughts, hopes, and concerns about the future for your team, unit, or organization. Tap into their aspirations and find out what would be exciting for them so that the vision you eventually create will resonate with the people who have to make it happen. See the box “A vision-creating exercise” for one way to do this.

Of course, you can’t stop there. You also need to incorporate your own thoughts and dreams. Some of the vision should be based on good common business acumen and insight. Scan the horizon. What’s happening in your industry or your sector? Are there unmet customer, market, or societal needs that your organization or unit has the capability to fulfill? Are there new technologies that you could leverage? How could you differentiate your organization from your competitors (or even from other units in the company)? More personally, what’s the impact that you’d like to have over the next few years or more? What would make you feel like you’ve really made a difference?

As you go through this thought process, start putting together options, choices, and what-if statements. For example, when Jim Wolfensohn was first thinking about the vision for the World Bank, he considered the possibility of focusing on measures of global economic development or aiming for a certain number of countries to achieve a target level of financial health. Eventually he settled firmly on the elimination of poverty. This was partly because of what he had heard during his trips to villages and neighborhoods in developing countries about unmet needs and decades of government inaction. But the decision also came from his own deep-seated conviction that the world could be a better place and the value that he put on improving individual lives. In other words, his starting point was not only intellectual, but was also shaped by his personal values.

A vision-creating exercise

One way to tap into your team members’ ideas about vision is to ask them to reinvent their official job titles so that they reflect the kind of value that they want to create and the impact that they aspire to have on customers. Professor Dan Cable from the London Business School, in his HBR article “Creative Job Titles Can Energize Workers,” describes how job titles improve employee satisfaction and engagement by giving people a better sense of how their work creates value and impacts customers. Disney is a prime example of this approach—calling theme park employees “cast members” and engineers “imagineers.” These titles are consistent with the company’s overall vision, which is “to make people happy.”

Lior Arussy, founder and CEO of the customer experience firm Strativity, uses this approach to help teams get excited about what they can potentially accomplish together, which is the essence of a team’s vision. For example, members of a sales team came up with titles such as “director of customer first impressions,” “customer dreams fulfillment manager,” and “red carpet roller.” All these indicate how the team wants to make customers feel special in their interactions with the company, which is a great basis for a team vision. (For more, see Arussy’s book Next Is Now: 5 Steps for Embracing Change—Building a Business That Thrives into the Future.)

As you think about creating a first draft vision for your organization or unit, think about how you can respond to the business issues but also be true to yourself. Consider, for example:

- What values and beliefs do you hold broadly and also specific to the mission of your organization or the work of your unit?

- How will your leadership values and beliefs actually shape the organization or your unit for the better?

Once you settle on a focus or theme for your draft vision, also consider how to be bold, audacious, and inspirational. Don’t settle for a vision that you know you can achieve, but rather something that will require creative thought, discovery, and experimentation. Remember that your purpose here is to inspire and energize, not to tell people what to do.

At the same time, don’t put the entire burden on yourself. As Kouzes and Posner point out, your job is not to be an emissary from the future with all the answers about what’s next for your organization. Rather your job is to start the conversation, point the way, and ask provocative questions that can help everyone get excited and inspired about the future.

Step 3. Engage stakeholders

Once you come up with your own draft ideas, you need to engage others in developing and fleshing them out. Involving others with different perspectives ensures that you create the best vision possible and also jump-starts buy-in throughout the organization. For example, at the World Bank, Wolfensohn and his senior leaders actively engaged different stakeholders in providing input and iteratively co-creating the vision based on his initial commitment to poverty eradication. By involving others, he created a vision that tapped into everyone’s passions, while also giving many people a voice in the process.

Every organization is different and every situation has its own unique characteristics and cast of characters, but to engage stakeholders, you first need to identify who to involve and then decide what the process of engagement will look like.

Who should you involve?

When choosing who to involve in the process, you’ll need to consider who can provide valuable input and give you different perspectives, and who needs to buy in and be engaged in the process. Here are some questions to consider:

- Do you want to limit the process to only a few people? Should you include direct reports or team members or open it up to a wider group of employees, or even the whole department or organization? Working with a few senior people is faster, and you can facilitate debates directly, but you may disenfranchise many others. You also won’t get as much input. On the other hand, when you engage more people, you also create expectations that you will consider their ideas, and they may be disappointed when their contributions don’t make the cut. So you need to manage expectations carefully.

- Do you want to engage your boss or other senior executives? At some point, your boss will need to endorse your vision, since he or she is also accountable for the direction and aspirations for the larger department or enterprise. So the question is really not whether to engage your boss, but when. It’s probably wise to alert your boss early on that you are rethinking or reshaping the vision, share your preliminary thoughts, and get his or her reactions and ideas. Then keep your boss abreast of the process and welcome input as you go along. By the time you present the vision to your senior executive and other senior people, they should already be on board. Similarly, if you are developing a vision for the enterprise, follow the same pattern, even up to and including the board.

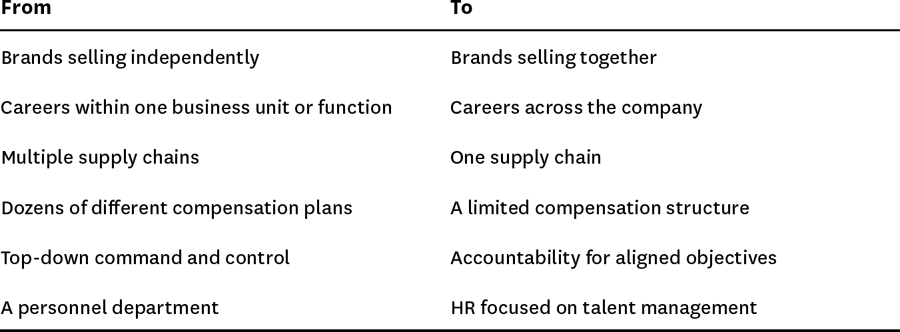

- Should you engage your customers? Your customers and others outside the organization can provide a valuable point of view. Visions are usually much more robust if they have an outside-in flavor and reflect the perspective of the user, customer, or recipient of the organization’s services, so we encourage you to bring your customers (internal or external) into the process. Take, for example, ConAgra Foods. When Gary Rodkin became the CEO in 2005, the firm was largely a holding company for prominent brands that it had acquired over the years (such as Hunt’s, Orville Redenbacher, Hebrew National, Chef Boyardee, Marie Calendar, Butterball, and many others). As he stepped into the role, Rodkin talked extensively with its customers and realized that they really didn’t view ConAgra as one company. Because it was dealing with each brand in a fragmented way, it was difficult for ConAgra to leverage its size in selling to large grocery retailers and outlets like Walmart. Rodkin’s interactions with customers informed his vision to turn ConAgra into an $18 billion “integrated operating company” with a basket of brands that could negotiate with Walmart and others from a much stronger position.

As you consider the engagement of customers, however, remember that you may already have all the input you need from ongoing contacts and listening sessions, satisfaction surveys, and day-today relationships developed over time. If that’s the case, getting more input from them might have diminishing returns. Toward the end of the process, however, you should share the emerging vision with some key customers to get their reactions, and use their feedback as a litmus test for whether you are on the right track.

What should the process be?

What’s the process for engaging people, creating ownership, and coming up with a vision that meets the criteria we’ve discussed?

As with the types of people you involve, it’s up to you to determine the right plan for your situation. There are some common approaches. One is to trigger the process with a rough first draft. Another is to provide a team with some key principles and then let team members sketch out a first draft (as Wolfensohn did at the World Bank). Another is to develop questions to address in focus groups or through interviews, and then use the emerging themes as a basis for the vision. As you decide on the right path, consider how you’ll incorporate your point of view from the previous step into this process. Do you want to insist on it (as a principle)? Do you want it to be a starting point for conversation (as a first draft)?

For example, when Wesleyan University was revisiting its vision, its president Michael Roth began by writing a draft vision with a few colleagues. But Wesleyan had many different constituencies (faculty from many disciplines, alumni, students, employees, community) who all saw things from their own perspectives, so he knew it would be intensely criticized by other stakeholders, and it was. As Roth described, the vision needed to capture “the tension between being outlandish and Avant Garde; with wanting to be effective and making serious contributions; and between inclusivity and generosity of spirit through an education steeped in liberal arts. We wanted it to be broad enough for both a chemist and a musicologist.” But as it circulated and his team changed it in response to the feedback, he saw it improving. Roth credits this process of passionate dialogue with the ultimate breadth of the vision.

That dialogue also needed to end. As he felt the team was getting close—that the vision was good enough—he announced that after ten more days, he would stop the process. The vision that Roth and Wesleyan ended up with was:

To provide an education in the liberal arts that is characterized by boldness, rigor, and practical idealism . . . where distinguished scholar-teachers work closely with students, taking advantage of fluidity among disciplines to explore the world with a variety of tools . . . while building a diverse, energetic community of students, faculty, and staff who think critically and creatively and who value independence of mind and generosity of spirit.

From Roth’s perspective, further debate would have added very little, made the statement overly complex, and not significantly improved the aspirational and exciting view of where the school was going.

Sometimes, of course, the approach to collaboration on a new vision is much less deliberate than this. Richard Ober, who is now CEO of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, was attending a conference earlier in his career when he was running a small but growing nonprofit. He had an epiphany about ideas that might be useful for a fund-raising brochure, so he drew a quick sketch of his ideas on a scrap of paper and then pulled it out a few days later at a development committee meeting. One of the board members said, “Hey, this isn’t just a brochure—it’s a vision for the whole organization,” and the rest of the committee agreed. Only then did Ober bring the brochure to others in the organization to flesh it out. He presented it at an all-staff meeting where he took suggestions for what had been left out and then asked those who had participated to draft a more complete version. Those people began to develop ownership of the vision as a result.

Involving others in the vision process can be challenging for a leader, particularly if you already have a strong view of where you want your organization or team to go. This kind of debate requires that leaders accept that they are not the font of all wisdom and, in fact, may not have the best answer—a lesson in humility. It requires that you listen more than you broadcast. But this act isn’t passive; it requires that you be highly engaged as you probe, ask questions, spot and challenge assumptions, and learn about different ways to frame the situation from many different people. It also requires you to actively synthesize many different ideas and viewpoints, and capture them in new, compelling ways. However deeply your own perspective is captured in the ultimate product, the process requires your creativity and energy for constant learning, pattern recognition, and effective articulation.

Step 4. Align people’s work with the vision

Once you’ve finalized the vision statement itself, it’s easy to think that you’re done, especially if you’ve already involved a significant number of people in your organization or team in the process. The reality, however, is that engaging your people in creating or reshaping a vision is just the beginning. The next and perhaps most crucial step is to make the vision come alive by helping everyone on your team or in your organization see how their own work relates to it.

Many leaders assume that if they lead some high-level presentations and town meetings, hang some posters, and disseminate some videos, their people will understand the firm’s vision and how their work contributes to it. While these are necessary vehicles for an intellectual understanding of where the organization is headed, they don’t particularly help staff align the vision with their day-to-day work or help them tap its emotional potential.

Make it a conversation

As part of your campaign to share the vision throughout your department or organization, insist that managers at all levels bring their people together to actively work through the connections. They should lead these conversations not just once as you disseminate the new vision, or even just yearly during the annual planning cycle, but at regular intervals so that staff can incorporate new projects, initiatives, and issues into the overall direction and the aspirational and emotional fabric.

You should lead some of these conversations yourself, but you should also encourage other leaders and managers in your unit to do the same with their people. In these sessions, ask everyone to think about how they can connect the dots between the work they’re doing and the vision of the company. What are the threads that tie together past initiatives and strategic directions with this vision? How have past efforts helped the company build capability over time and move toward the vision? What gets them excited about the vision? And if some of their projects or activities don’t connect to the vision, should they be changed or discontinued?

Tell a story

A key skill as you sell a vision is the ability to tell a good story about it. Some business schools even include storytelling as part of their core curriculum. A story can connect the company’s vision to real people, real situations, and real emotions so that people feel that their work makes a difference.

At the World Bank, for example, Wolfensohn and his team made the vision of poverty elimination come alive by describing particular projects and villages where the Bank was making a difference in real people’s lives. Regional and country leaders at the Bank then did the same with their people. At ConAgra, Rodkin explained the vision of becoming an integrated operating company by telling stories about how real people in the company were working together across product areas and leveraging procurement scale to get better results.

At Xerox, Anne Mulcahy took the storytelling approach quite deliberately during her turnaround of the company in the late 1990s. In the midst of an intensive effort to save the company from bankruptcy, Mulcahy realized that her people were yearning for a higher level of purpose beyond day-to-day problem solving and operations. So she worked with one of her team members to write a fictional Wall Street Journal story, set several years in the future, that described how Xerox had pulled itself out of the crisis and made itself successful. Mulcahy hoped she could create “a story that people would see themselves in and be able to say, ‘OK, I want to be part of that.’” It worked so well that for years afterward, she had to keep reminding people that the piece was fictional.

Another way to tell a story is to visualize it. A tool called a “from-to chart” can help capture the idea of where you are now versus where you are going to emphasize the direction that you are setting. (Table 1–5 shows an example of a from-to chart from Rodkin’s vision at ConAgra.)

Unless you take the time to help your people understand the ways that the vision connects to their work and to their personal values and emotions, they may experience your new vision as a slogan on the wall or as one more change in a series of random and arbitrary directives with no rhyme or reason. By putting the vision into the context of employees’ own experience, you’ll have more success actually moving people in the direction that you’ve set—and making the vision into the best strategic unifier and motivator that it can be for your whole organization or team.

Questions to Consider

- Vision alignment. Does your team have a clear, shared vision for where it is going? If so, does it align with your personal vision for the team and the larger company vision?

- Timing. Is it time to revise or recraft the vision for your team? What would be the purpose of working on the vision now? How would it make a difference?

- Future focus. To what extent does your team’s vision give everyone an exciting aspiration for the future? Does the vision look far enough ahead to get everyone thinking creatively about their work?

- Being bold. What big ideas do you have about your team’s vision? Can you paint a picture of the future that people would be excited about working toward—and that would engage their hearts as well as their heads?

- Stakeholders. Who do you need to involve in crafting or modifying your team’s vision? Team members? Internal or external customers? Your boss? Other stakeholders?

- Process. What process will you use to craft or modify your team’s vision? Will you take a first cut? Can you assign the work to a team? Should you bring everyone together? Can you use virtual conversations or your internal social media?

- Communication. What stories can you use to bring your vision to life so it’s not just a slogan or catchphrase? Can you portray the vision with a from-to chart?