Monopoly in the 20th Century: Roosevelt Warns of Concentrated Wealth and Fascism

On April 20, 1938, the Associated Church Press—a group of reporters for religious magazines and newspapers—met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in Washington, DC. One of their first questions was, “I would like to ask you, how great is the danger of fascism in this country? We hear about fascism-baiting in the United States.”

FDR’s answer was blunt, and it reveals a lot to us today of how Americans thought of “fascist” enterprises back in that day.

“I think there is danger,” he replied to the question, “because every time you have the breaking down or failure of some process we have been accustomed to for a long time, the tendency is for that process, because of the breakdown, to get into the hands of a very small group.”

He then spoke directly to the issue of centralized—and distant—ownership or control of business by powerful interests, in this case the banks in New York. FDR contracted adult polio at age 39 and was partially paralyzed from it, so he spent a lot of time in Warm Springs, Georgia, where people stricken by polio could float and lightly exercise in the warm, mineral-rich water. On several of his visits, he’d heard from the people who lived in Georgia that they weren’t happy with the way the “local” utility was refusing to extend electric power out to rural areas like the ones around Warm Springs.

“One of our southern states that I spend a lot of time in,” he said, giving an example to illustrate his point, “has a very large power company, the Georgia Power Company. There are a lot of people in Georgia that want to own and run Georgia power, but it is owned by Commonwealth and Southern in New York City. . . . Georgia has plenty of money with which to extend electric light lines to the rural communities, and the officers of Georgia Power Company themselves want it Georgia-owned or Georgia-run. But they have to go to New York for the money. If it were not for that, we would not have any utility problem, and all of them would be owned in the districts which they serve, and they would get rid of this financial control.”1

But it wasn’t just that rural Georgia was being screwed by profit taking in New York and was powerless in the face of it. The controlling of electricity in Georgia by this for-profit privately owned monopoly meant that rural Americans in that state would still have to light their homes with kerosene and couldn’t even turn on a radio.

It also meant that workers were often stripped of appropriate compensation for their work. “You take the new lumber companies that want to start on this wonderful process of making print paper out of yellow pine,” FDR continued. “One reason for the low wages of the workers in the pulp mills of Mississippi, Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina is that practically all profits go north; they do not stay south. If the profits stayed south, the whole scale of living would go up.”

And then he brought it all back to the word fascism, which the dictionaries of the day defined as the merger of state and corporate power, a process that was well underway in Italy— where Mussolini had dissolved the elected parliament and replaced it with the Chamber of the Fascist Corporations, where the Italian equivalent of each congressional district was represented by its largest industry instead of an elected member—and Hitler and Tojo had both moved to bring powerful business leaders and industrial tycoons into government.

“I am greatly in favor of decentralization,” FDR wrapped up his answer to that question, “and yet the tendency is, every time we have trouble in private industry, to concentrate it all the more in New York. Now that is, ultimately, fascism.”

Nine days later, President Roosevelt brought up the issue again in his April 29, 1938, “Message to Congress on the Concentration of Economic Power.”2

Unhappy events abroad have re-taught us two simple truths about the liberty of a democratic people.

The first truth is that the liberty of a democracy is not safe if the people tolerate the growth of private power to a point where it becomes stronger than their democratic state itself. That, in its essence, is fascism—ownership of government by an individual, by a group, or by any other controlling private power.

The second truth is that the liberty of a democracy is not safe if its business system does not provide employment and produce and distribute goods in such a way as to sustain an acceptable standard of living.

Speaking of the captains of industry who, in the election two years earlier he had said, “hate me, and I welcome their hatred,” FDR laid out the state of things that three previous Republican administrations (Harding, Coolidge, Hoover) and their deregulatory fervor had brought about:

Among us today a concentration of private power without equal in history is growing.

This concentration is seriously impairing the economic effectiveness of private enterprise as a way of providing employment for labor and capital and as a way of assuring a more equitable distribution of income and earnings among the people of the nation as a whole.

Shifting from the rhetorical to the concrete, he gave a few startling examples:

Statistics of the Bureau of Internal Revenue reveal the following amazing figures for 1935:

Ownership of corporate assets: Of all corporations reporting from every part of the nation, one-tenth of 1 percent of them owned 52 percent of the assets of all of them.

And to clinch the point: Of all corporations reporting, less than 5 percent of them owned 87 percent of all assets of all of them.

Income and profits of corporations: Of all the corporations reporting from every part of the country, one-tenth of 1 percent of them earned 50 percent of the net income of all of them.

And to clinch the point: Of all the manufacturing corporations reporting, less than 4 percent of them earned 84 percent of all the net profits of all of them.

FDR pointed out that the Republican Great Depression (what it was called until the early 1950s3) had played a role in this process by weakening small businesses and often forcing them to sell out to larger interests or to mortgage themselves to big players, generally in distant cities.

The Republican policies he was noting produced vast wealth for a small number of monopolists and stripped workers of their wages and security. And the monopolists were, throughout the Roaring Twenties, using the Harding/Coolidge/Hoover deregulation of the marketplace to concentrate ownership of America’s productive enterprises in their own tiny hands. The peak of the trend had been in the summer of 1929, when the market was at its top.

“[I]n that year,” FDR told Congress, “three-tenths of 1 percent of our population received 78 percent of the dividends reported by individuals. This has roughly the same effect as if, out of every 300 persons in our population, one person received 78 cents out of every dollar of corporate dividends, while the other 299 persons divided up the other 22 cents between them.”

But it wasn’t just wealth in the form of stock and business ownership that was concentrating. As the circle of ownership of entire industries was becoming smaller and smaller, that increasingly powerful group of men (and they were all men) were able to redefine the workplace so they could take more and more out of the paychecks of their workers and keep it for themselves.

By 1936, FDR said, “[f]orty-seven percent of all American families and single individuals living alone had incomes of less than $1,000 for the year; and at the other end of the ladder a little less than 1 percent of the nation’s families received incomes which in dollars and cents reached the same total as the incomes of the 47 percent at the bottom.”

Ask “average men and women in every part of the country,” FDR said, what this concentration of wealth and its attendant political power meant. “Their answer,” he told Congress, “is that if there is that danger, it comes from that concentrated private economic power which is struggling so hard to master our democratic government.”

They were doing it through monopoly. FDR said that “interlocking spheres of influence over channels of investment and through the use of financial devices like holding companies and strategic minority interests” meant that “[t]he small businessman is unfortunately being driven into a less and less independent position in American life.”

Big business, the president said, while “masking itself as a system of free enterprise after the American model . . . is in fact becoming a concealed cartel system after the European model.”

He wrapped up the speech with a specific call to take on monopoly in America. It was a call that echoed through the next three decades. “Once it is realized that business monopoly in America paralyzes the system of free enterprise on which it is grafted,” FDR said, “and is as fatal to those who manipulate it as to the people who suffer beneath its impositions, action by the government to eliminate these artificial restraints will be welcomed by industry throughout the nation.”

Monopoly and Fascism in America Today

Today, things are even worse than in FDR’s time.

“The top 1 percent of families captured 58 percent of total real income growth per family from 2009 to 2014,” wrote economist Emmanuel Saez for the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.4

In large part, the concentration of both wealth and income has come about in the era since the Reagan presidency and the introduction of “Reaganomics.” In the 40 years prior to Reagan, income and wealth among working people was growing at a faster rate than it was for the top 1%. Since Reaganomics was instituted—a system within which we’re still operating— the wealth and income of the top 1% has exploded.

When Reagan came into office in 1981 and welcomed the monopolists back into government, everything shifted. Where we once had wide and celebrated local and regional diversity in beer brewing, for example (remember “Milwaukee’s Finest” and when Coors had to be smuggled out of Colorado?), today we have instead two corporations that produce over 90% of all the beer consumed in the United States, and one of the two, Anheuser-Busch, is now largely owned by Belgian and Brazilian investors.5

If you want to relax with the internet instead of a beer, that marketplace is also highly concentrated.

While South Koreans get internet speeds 200 times faster than what most Americans get, and pay only $27 a month for their service, Susan P. Crawford, author of Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age and former board member of ICANN, told me that the average American consumer pays around $90 a month for a cell phone with a data plan, compared with the European average of just $19 (and the coverage is better and the data is both faster and unlimited).

Why? Because the European Union doesn’t tolerate monopolies as the United States does. There are hundreds of small and feisty competitors across the continent.

On Wall Street, the 20 biggest banks own assets equivalent to 84% of the nation’s entire gross domestic product (GDP). And just 12 of those banks own 70% of all the banking assets. That means our entire banking system relies on just a few whales that must be saved at all costs from going belly up, or else the entire system goes belly up.

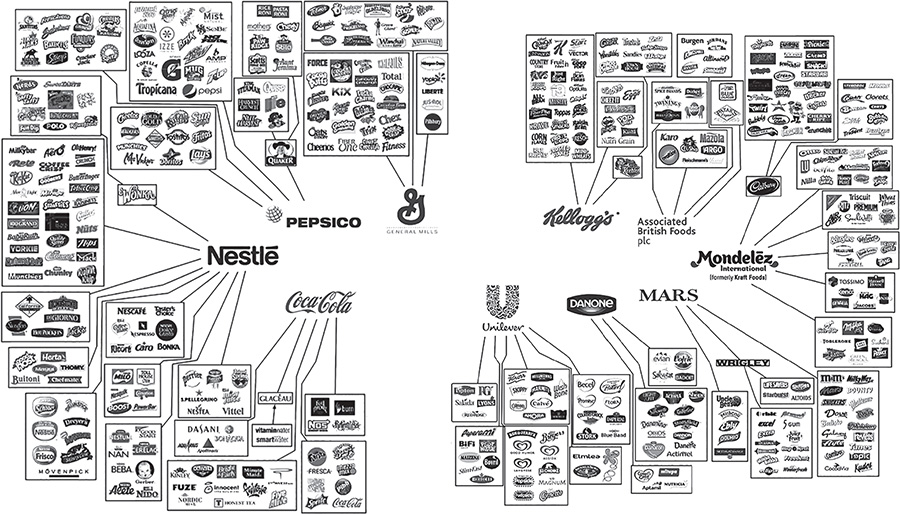

And consider our food industry. According to Tom Philpott at Mother Jones magazine, agriculture oligopolies exist from farm to shelf. Just four companies control 90% of the grain trade. Just three companies control 70% of the American beef industry. And just four companies control 58% of the US pork and chicken producing and processing industries.

On the retail side, Walmart controls a quarter of the entire US grocery market. And just four companies produce 75% of our breakfast cereal, 75% of our snack foods, 60% of our cookies, and half of all the ice cream sold in supermarkets around the nation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The food and beverage brands that own the grocery store.6 Source: Joki Gauthier for Oxfam 2012 (https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/research-publications/behind-thebrands/). Reproduced with the permission of Oxfam, Oxfam House, John Smith Drive, Cowley, Oxford OX4 2JY, UK (www.oxfam.org.uk). Oxfam does not necessarily endorse any text or activities that accompany the materials.

Then there’s the health insurance market. Just four health insurance companies—UnitedHealth Group, WellPoint, Aetna, and Humana—control three-quarters of the entire health insurance market. And, as a 2007 study by the group Health Care for America Now uncovered, in 38 states, just two insurers controlled 57% of the market. In 15 states, one insurer controlled 60% of the market.

Since there’s no functional competition in such a market, prices continue to go higher and higher while the profits for these whales skyrocket too.

In the cellular phone market, just four companies—AT&T Mobile, Verizon Wireless, T-Mobile, and Sprint Nextel— control 89% of the market. And in the internet arena, just a single corporation—Comcast—controls more than half of the market.

As Adam Smith pointed out, and the Founders of this republic well knew, capitalism is a game that can work for the average person and the small business, but only when the rules of the game are set that way. Re-rig those rules to give disproportionate power to the very wealthy, and we slide into what Franklin Roosevelt called fascism.

Since money often equals political power, and political power can be used to rewrite the rules of business and tax law to further concentrate and enhance wealth and income for those paying the lobbyists and members of Congress, this situation not only represents the economic threat of making the marketplace more fragile and liable to crashes like what happened in 1929 but also represents a threat to democracy itself.

Most Americans would be highly offended if the NFL rules were changed to allow whichever team had the most money to have an extra three players on the field at all times. But that’s exactly what Reaganomics and its deregulation have brought us in our marketplaces; it’s the staggering difficulty that every small business in America faces today.

To understand how to fix this situation so that America’s small businesses and middle class can once again thrive, it’s important to understand the factors at play that created the vibrant, localized American economy that was the hallmark of mid-20th-century America.

Where Did America’s Middle Class Come From?

We hear a lot about “the good old days,” as if to suggest that America was always an economically strong nation with a vibrant middle class. But the fact is that we got really, really rich—we being the bottom 90% of Americans—in just a few decades after World War II, as a result of Franklin Roosevelt putting into place the economic theories of Adam Smith and John Maynard Keynes, and those policies holding steady until the election of Ronald Reagan.

In 1900, the average yearly household income was $4497— the equivalent of around $13,800 in today’s dollars.8 That kind of income today guarantees a life of want and poverty, and it did in 1900 as well. The only buffer then was the family farm; while today only 1% of Americans live and work on farms, in 1900 it was around 40%.9

My wife’s grandmother, who was born in 1905, lived on a small (100 acres) farm in central Michigan throughout the Republican Great Depression and for a few decades after-ward. I remember Grandma telling us stories about how she bought two dresses and a big bag of salt and a big bag of sugar once a year from the Sears catalog; otherwise, everything they needed was locally sourced or grown. They were “poor,” but they weren’t experiencing what today we’d call poverty.

So although there were plenty of multimillionaires in 1900—and, in today’s dollars, a large handful of billionaires as well—about 40% of America was buffered from the ravages of deep poverty by their farms and their neighbors, while half of America was struggling to live in cities and hanging on to the economic and social edge, barely able to make it year to year.

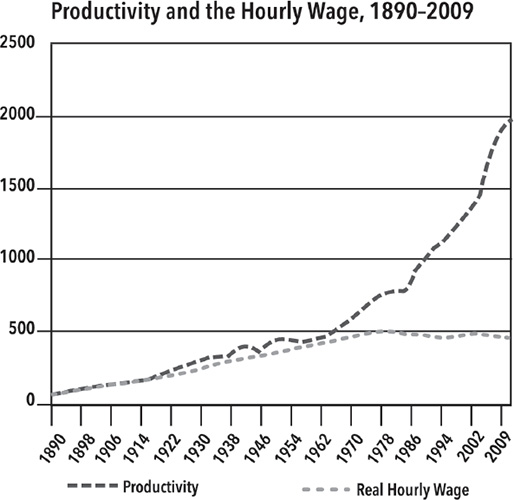

From 1800 until Reagan—except for the hiccup of the Roaring Twenties and its Republican Great Depression— wages pretty much tracked productivity. The core concept of business was that if a workforce can produce more goods in the same time without sacrificing quality, they should share in the increased profits from the increased sales, if for no other reason than Henry Ford’s—so that they’ll stick around and work, and the company doesn’t have to incur the costs of hiring and retraining associated with employee turnover.

In 1913, most auto manufacturers were paying their employees around $2.25 a day, the equivalent of around $14,000 a year in today’s dollars, just slightly below our 2019 federal minimum wage of $7.25. In 1914, Henry Ford famously more than doubled his workers’ pay to $5 a day, or $31,000 a year10 in today’s dollars, in part because of the dramatic increase in per-worker productivity he was getting—and wanted to keep—from his assembly line and in part to keep these now highly productive workers on the job; his main incentive was to reduce employee turnover.11

World War I and the Republican Great Depression introduced serious noise into the employment and wage statistics until FDR came along and righted the ship of state, but with increasing productivity came increasing wages. By 1950, the yearly average worker income in the United States was clipping along at around $3,00012 (household income was $3,300, but most households had a single wage earner),13 or $31,465 per year in today’s dollars.14

As people returning from World War II were finishing trade school and college and entering the workforce, and the stimulative effect of the GI Bill was raising demand for goods and services, that number had grown to $5,700 a year in 1960, or $48,600 a year per household (there were still few multiple-worker households) in 2019 dollars.

Productivity continued to increase, as did wages, hitting a peak in 1970 of $9,430 per year,15 or $61,400 in today’s dollars. Employers were making more and more money and, trying to avoid paying the top marginal tax rate of 91% (up until 1967 and 73% thereafter), they were plowing that money back into their companies and their employees.

Workers had good union jobs, good benefits in addition to that substantial paycheck, home and car ownership, and annual vacations; they could send their kids to college and even own a small summer home. These were all parts of being “middle class” in America.

Where Did America’s Middle Class Go?

Then came the twin hits of trade liberalization in the 1970s— cutting tariffs and allowing cheap imports, so that American workers were competing with lower-paid, then-mostly Japanese workers—and Reagan’s massive tax cuts of the 1980s, which explicitly encouraged employers and CEOs to drain as much money out of their companies as they could rather than reinvest it or pay their employees well.

Since the 1970s, productivity has increased by 146%,16 but wages have actually either stagnated (if looking at household incomes; today many more are two-wage-earner households) or fallen (looking at individual incomes). CEO compensation has rocketed from 30 times the average worker’s to hundreds of times, in some industries even thousands of times (for example, Coca-Cola’s CEO, James Quincey, gets paid $16.7 million per year—or 1,016 times the typical employee’s pay).17

The Census Bureau reports that 2016 average household income was $57,60018—the combined income of (generally) at least two workers, or one worker working more than a single full-time job—a significant fall from its 1970 peak of $61,400 (in today’s dollars) for an individual worker with a single full-time job.

Because of Reaganomics, today it takes two or more people working in a household to maintain the standard of living that one worker could sustain prior to the 1980s.

From 1950 to 1970, both wages and productivity pretty much doubled, an increase of around 100% (it was in the high 90s, but let’s round off to keep things simple).19

Using 1950 as a benchmark, between 1970 and 2019 wages went up from around 97% to 114%, but productivity went from 98% above the 1950 number to 243%.20

That 130% increase in productivity while holding wages steady led to a massive increase in corporate profits. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (which compiles these statistics), the total profit of all American corporations in 1950 was $33 billion, or about $346 billion in today’s dollars. In 1960, it was $55 billion, or $469 billion today. The year 1970 saw total corporate profits at $86 billion, or $560 billion in today’s money.21

The ’70s and ’80s were the years of great change, with the end of Bretton Woods (the 1944 international conference that established the modern system of monetary management, including rules for commercial and financial relations among the United States, Canada, Western European countries, Australia, and Japan) and many tariffs in the 1970s, and Reagan’s massive tax cuts (and anti-union crusades) in the 1980s.

By 1990, corporate quarterly (multiply by 4 for annual) profits were at $413 billion, or $798 billion in today’s dollars. In 2000, they hit $770 billion quarterly, or $1.13 trillion a quarter today.

A decade later, in 2010, they were at $1,890 billion (and this after the Great Recession of 2008–2009) every quarter, or $2.19 trillion in today’s dollars.

In 2018, the last year the Fed reported as of this writing, corporate profits were at $2.223 trillion—nearly $9 trillion a year or almost half of the entire nation’s GDP.22

Profits are a pretty reasonable indicator of things, as they’re more independent of overall economic activity than most metrics like GDP. From 1970 to today, we’ve seen a more than 400% increase in money going to the top as profits, compared with a rise in household income of around 15% (and a drop in individual income).

Since profits represent what’s left over after all the other bills are paid and investments made, for profits to have risen so dramatically since roughly the Reagan years, what happened?

Why didn’t all that money go, as it once did, to increases in wages so that workers were sharing in the increasing corporate prosperity they were helping create?

Monopoly plays a huge role in the answer.

How Reaganomics Killed the Jetsons

Ms. Mornin: That’s good, because I work three jobs and I feel like I contribute.

President Bush: You work three jobs?

Ms. Mornin: Three jobs, yes.

President Bush: Uniquely American, isn’t it? I mean, that is fantastic that you’re doing that.

—President George W. Bush, Omaha, Nebraska, Town Hall, February 2005

President George W. Bush (and President Donald Trump, who brags about low unemployment although virtually all newly created jobs are low-paying) might have thought it was “fantastic” that one of his supporters had to work three jobs to pay her family’s bills, but most Americans wouldn’t agree, and never have. The movement to restrict labor to 10 hours a day (from the then-widespread 14-hour day) got underway in the United States and Great Britain in the 1830s23 and reached its peak here after the Civil War, and in England in 1847 with the passage of the Factories Act.24

The fight for the eight-hour day was kicked off in a big way by President Ulysses S. Grant in 1869, when he declared by proclamation that it should be the industrial standard of the United States.25 The United Mine Workers won it in 1898, and in 1926 Henry Ford adopted it, after years of agitation by his workers. The great Flint Sit-Down Strike of 1937 caused its adoption across the auto industry and most others.

In 1980, the year before Reagan kicked off his “revolution,” the 40-hour work week was standard all across America, although since then the hours that workers put in have steadily risen as the rate of unionization has fallen from around a third of all workers when Reagan was inaugurated to around 6% of the private workforce today.

But this was not the state of life for human beings during the vast majority of our history.

Back in the early 1960s, Richard Borshay Lee spent almost two years with the !Kung Bushmen in a part of what is now Botswana called Dobe. He wrote,

In all, the adults of the Dobe camp worked about two and a half days a week. Since the average working day was about six hours long, the fact emerges that !Kung Bushmen of Dobe, despite their harsh environment, devote from twelve to nineteen hours a week to getting food. Even the hardest-working individual in the camp, a man named ≠oma who went out hunting on sixteen of the twenty-eight days, spent a maximum of thirty-two hours a week in the food quest.26

Marshall Sahlins, in his 1974 book Stone Age Economics, estimated, based on the fieldwork of Lee and others, that the average hunter-gatherer worked between three and five hours a day.27 Which Time magazine posited, in 1966, was where we’d be by the year 2000, a third of a century off in the future.28

Just a few years earlier, Hanna-Barbera had produced a cartoon show called The Jetsons, about a family in the future, where George Jetson, the family patriarch, worked at Space-ley’s Sprockets, doing the difficult work of pushing a button every 10 minutes or so. The future was going to be, at least for working people, easier.

And, indeed, Time noted, “By 2000, the machines will be producing so much that everyone in the U.S. will, in effect, be independently wealthy. With Government benefits, even non-working families will have, by one estimate, an annual income of $30,000–$40,000. How to use leisure meaningfully will be a major problem.”29

And that was $30,000 to $40,000 in 1966 dollars, which would be roughly $199,000 to $260,000 in today’s dollars.

Or, instead of taking a paycheck that was so much larger, American workers could take the same pay they already had and, like George Jetson, just push a button for three or four hours a day.

Ask anybody who was teenage or older in the 1960s: this was the big sales pitch for automation and the coming computer age. Americans looked forward to increased productivity from robots, computers, and automation translating into fewer hours worked or more pay, or both, for every American worker.

There was good logic behind the idea in 1966, because back then, that was how things actually worked.

The premise was simple. With better technology, companies would become more efficient and make more things in less time. Revenues would skyrocket, and Americans would bring home bigger and bigger paychecks, all the while working less and less. By the year 2000, Time posited, we would enter what was then referred to as “The Leisure Society.”

Futurists speculated that the biggest problem facing America in the future would be just how the heck everyone would use all their extra leisure time!

Then came 1980.

The industrialists and financiers who helped put Reagan in office and cheered him on with their think tanks and media also saw this increased productivity coming, and with it a huge opportunity. What if all that productivity—and the extra revenue it would create—could go to them instead of to the workers?

All it would take would be to break the unions, lower top tax rates so that the money didn’t end up with the government instead, and reconfigure corporate governance laws to let small- and medium-sized companies be gobbled up by giant corporations that could provide CEOs and senior executives with pay in the million-dollars-a-month to million-dollars-a-day range.

Reagan obligingly saw to it all, and right-wing think tanks and their monopolist funders have kept us there.

Reaganomics Ensured American Leisure for the Few, Not the Many

As productivity continued to rise, due to increasing automation and better technology, so too would everyone’s wages. Or so went the theory. The glue holding this logic together was the then-top marginal income tax rate. In 1963, just before the Time article was written, the top marginal income tax rate was 90%. What that did was encourage CEOs to keep more money in their businesses: to invest in new technology, to pay their workers more, to hire new workers and expand.

Figure 2. Productivity and the hourly wage, 1890–2009.

Sources: US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics; US Department of the Census, after D. Hayes, Historical Statistics of the United States (2006). Based on a graph by Jason Ricciuti-Borenstein.

After all, what’s the point of sucking millions and millions of dollars out of your business if it’s going to be taxed at 90% (or even the 70% that President Lyndon Johnson lowered it to in 1966)?

According to this line of reasoning, if businesses were suddenly to become way more profitable and efficient thanks to automation, then that money would flow throughout the business—raising everyone’s standard of living and increasing everyone’s leisure time, from the CEO to the janitor.

But when Reagan dropped that top tax rate down to 28%, everything changed. Now, as businesses became far more profitable, there was a far greater incentive for CEOs to pull those profits out of the company and pocket them, because they were suddenly paying an incredibly low tax rate.

And that’s exactly what they did.

All those new profits, thanks to automation, that were supposed to go to everyone, giving us all bigger paychecks and more time off, went to the top.

Suddenly, the symmetry in the productivity/wages chart broke down. Productivity continued increasing, since technology continued improving, and revenues and profits kept increasing with it.

But wages stayed flat.

And, again, since greater and greater profits could be sucked out of the company and taxed at lower levels, there was no incentive to reduce the number of hours everyone had to work.

In the 1950s, before that Time magazine article predicting the Leisure Society was written, the average American working in manufacturing put in about 42 hours of work a week. Today, the average American working in manufacturing puts in about 40 hours of work a week. This means that even though productivity has increased 400% since 1950, Americans in manufacturing are working, on average, only two fewer hours a week.

If productivity is four times higher today than in 1950, then Americans should be able to work four times less, or just 10 hours a week, to afford the same 1950s lifestyle when a family of four could get by on just one paycheck, own a home, own a car, put their kids through school, take a vacation every now and then, and retire comfortably.

That’s the definition of the Leisure Society: 10 hours of work a week, and the rest of the time spent with family, with travel, with creativity, with whatever you want. And if our tax laws and our corporate anti-monopoly laws that restrained the worst corporate bad behavior had stayed the same as they were in 1966, we might well be either working 10 hours a week for around $50,000 a year in income, or working 40-hour weeks for over $200,000 a year.

But all of this was washed away by the Reagan tax cuts. Those trillions of dollars that would have gone to workers? They went into the estates and stock portfolios of the top 1%. Combine this with Reagan’s brutal crackdown on striking PATCO (Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization) members that kicked off a three-decades-long assault on another substantial pillar of the middle class—organized labor—and life today is anything but leisurely for working people in America.

More Unequal than Rome

Instead of leisure, working people got feudalism.

From 1947 to 1981, all classes of Americans saw their incomes grow together; as a result of the Reagan tax cuts, that era ended and a new era of Reaganomics began. Since then, only the wealthiest among us have gotten rich from economic boom times.

Today, workers’ wages as a percentage of GDP are at an all-time low. Yet, corporate profits as a percentage of GDP are at an all-time high.

The top 1% of Americans own 40% of the nation’s wealth. In fact, just 400 Americans own more wealth than 150 million other Americans combined, and they pay lower taxes than anybody in the bottom half of American families economically.30

Walmart, Inc., the world’s largest private employer, personifies this inequality best. It’s a corporation that in 2011 gained more revenue than any other corporation in America. It raked in $16.4 billion in profits. It pays its employees minimum wage.

And the Walmart heirs, the Walton family, who occupy positions six through nine on the Forbes 400 Richest Americans list, own roughly $100 billion in wealth, which is more than the bottom 40% of Americans combined. The average Walmart employee would have to work 76 million 40-hour weeks to have as much wealth as one Walmart heir.

Through some interesting historical analysis, historians Walter Scheidel and Steven Friesen calculated that inequality in America today is worse than what was seen during the Roman era.31 Thus the top 1%, just like the Roman emperors, got their Leisure Society, and they’ve used their financial power to capture the US government to protect their Leisure Society.

How the Monopolists Stole the US Government

Because the Founders set up America to be resistant to the coercive and corruptive influence of monopoly and vested interest, the monopolists didn’t have any direct means of taking over the American government. So, two processes were necessary.

First, they knew that they’d have to take over the government. A large part of that involved the explicit capture of the third branch of government, the federal judiciary (and particularly the Supreme Court), which meant taking and holding the presidency (because the president appoints judges) at all costs, even if it required breaking the law; colluding with foreign governments, monopolies, and oligarchs; and engaging in massive election fraud, all issues addressed in previous Hidden History books.

Second, they knew that if they were going to succeed for any longer than a short time, they’d need popular support. This required two steps: build a monopoly-friendly intellectual and media infrastructure, and then use it to persuade people to distrust the US government.

Lewis Powell’s 1971 memo kicked off the process.

Just a few months before he was nominated by President Richard Nixon to the US Supreme Court, Powell had written a memo to his good friend Eugene Sydnor Jr., the director of the US Chamber of Commerce at the time.32 Powell’s most indelible mark on the nation was not to be his 15-year tenure as a Supreme Court justice but instead that memo, which served as a declaration of war against both democracy and what he saw as an overgrown middle class. It would be a final war, a bellum omnium contra omnes, against everything FDR’s New Deal and LBJ’s Great Society had accomplished.

It wasn’t until September 1972, 10 months after the Senate confirmed Powell, that the public first found out about the Powell memo (the actual written document had the word “Confidential” at the top—a sign that Powell himself hoped it would never see daylight outside of the rarified circles of his rich friends). By then, however, it had already found its way to the desks of CEOs all across the nation and was, with millions in corporate and billionaire money, already being turned into real actions, policies, and institutions.

During its investigation into Powell as part of the nomination process, the FBI never found the memo, but investigative journalist Jack Anderson did, and he exposed it in a September 28, 1972, column in the Washington Post titled, “Powell’s Lesson to Business Aired.” Anderson wrote, “Shortly before his appointment to the Supreme Court, Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. urged business leaders in a confidential memo to use the courts as a ‘social, economic, and political’ instrument.”33

Pointing out that the memo hadn’t been discovered until after Powell was confirmed by the Senate, Anderson wrote, “Senators . . . never got a chance to ask Powell whether he might use his position on the Supreme Court to put his ideas into practice and to influence the court in behalf of business interests.”34

This was an explosive charge being leveled at the nation’s rookie Supreme Court justice, a man entrusted with interpreting the nation’s laws with complete impartiality. But Anderson was a true investigative journalist and no stranger to taking on American authority or to the consequences of his journalism. He’d exposed scandals from the Truman, Eisenhower, Johnson, Nixon, and Reagan administrations. In his report on the memo, Anderson wrote, “[Powell] recommended a militant political action program, ranging from the courts to the campuses.”35

Powell’s memo was both a direct response to Franklin Roosevelt’s battle cry decades earlier and a response to the tumult of the 1960s. He wrote, “No thoughtful person can question that the American economic system is under broad attack.”36

When Sydnor and the Chamber received the Powell memo, corporations were growing tired of their second-class status in America. The previous 40 years had been a time of great growth and strength for the American economy and America’s middle-class workers—and a time of sure and steady increases of profits for corporations—but CEOs wanted more.

If only they could find a way to wiggle back into the minds of the people (who were just beginning to forget the monopolists’ previous exploits of the 1920s), then they could get their tax cuts back; they could trash the “burdensome” regulations that were keeping the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the food we eat safe; and the banksters among them could inflate another massive economic bubble to make themselves all mind-bogglingly rich. It could, if done right, be a return to the Roaring Twenties.

But how could they do this? How could they persuade Americans to take another shot at what was widely considered a dangerous “free market” ideology and economic framework that had crashed the economy in 1929?

Lewis Powell had an answer, and he reached out to the Chamber of Commerce—the hub of corporate power in America—with a strategy. As Powell wrote, “Strength lies in organization, in careful long-range planning and implementation, in consistency of action over an indefinite period of years, in the scale of financing available only through joint effort, and in the political power available only through united action and national organizations.” Thus, Powell said, “the role of the National Chamber of Commerce is therefore vital.”37

In the nearly 6,000-word memo, Powell called on corporate leaders to launch an economic and ideological assault on college and high school campuses, the media, the courts, and Capitol Hill. The objective was simple: the revival of the royalist-controlled “free market” system. As Powell put it, “[T]he ultimate issue . . . [is the] survival of what we call the free enterprise system, and all that this means for the strength and prosperity of America and the freedom of our people.”

The first front that Powell encouraged the Chamber to focus on was the education system. “[A] priority task of business—and organizations such as the Chamber—is to address the campus origin of this hostility [to big business],” Powell wrote.38 What worried Powell was the new generation of young Americans growing up to resent corporate culture. He believed colleges were filled with “Marxist professors” and that the pro-business agenda of Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover had fallen into disrepute since the Great Depression. He knew that winning this war of economic ideology in America required spoon-feeding the next generation of leaders the doctrines of a free-market theology, from high school all the way through graduate and business school.

At the time, college campuses were rallying points for the progressive activism sweeping the nation as young people demonstrated against poverty, the Vietnam War, and in support of civil rights. Powell proposed a list of ways the Chamber could retake the higher-education system. First, create an army of corporate-friendly think tanks that could influence education. “The Chamber should consider establishing a staff of highly qualified scholars in the social sciences who do believe in the system,” he wrote.39

Then, go after the textbooks. “The staff of scholars,” Powell wrote, “should evaluate social science textbooks, especially in economics, political science and sociology. . . . This would include assurance of fair and factual treatment of our system of government and our enterprise system, its accomplishments, its basic relationship to individual rights and freedoms, and comparisons with the systems of socialism, fascism and communism.”40

Powell argued that the civil rights movement and the labor movement were already in the process of rewriting textbooks. “We have seen the civil rights movement insist on re-writing many of the textbooks in our universities and schools. The labor unions likewise insist that textbooks be fair to the viewpoints of organized labor.”41 Powell was concerned that the Chamber of Commerce was not doing enough to stop this growing progressive influence and replace it with a pro-plutocratic perspective.

“Perhaps the most fundamental problem is the imbalance of many faculties,” Powell pointed out. “Correcting this is indeed a long-range and difficult project. Yet, it should be undertaken as a part of an overall program. This would mean the urging of the need for faculty balance upon university administrators and boards of trustees.”42 As in, the Chamber needed to infiltrate university boards in charge of hiring faculty to make sure that only corporate-friendly professors were hired.

Powell’s recommendations targeted high schools as well. “While the first priority should be at the college level, the trends mentioned above are increasingly evidenced in the high schools. Action programs, tailored to the high schools and similar to those mentioned, should be considered,” he urged.43

Next, Powell turned to the media, instructing that “[r]eaching the campus and the secondary schools is vital for the long-term. Reaching the public generally may be more important for the shorter term.” Powell added, “It will . . . be essential to have staff personnel who are thoroughly familiar with the media, and how most effectively to communicate with the public.” He advocated that the same system “applies not merely to so-called educational programs . . . but to the daily ‘news analysis’ which so often includes the most insidious type of criticism of the enterprise system.”

Following Powell’s lead, in 1987 Reagan suspended the Fairness Doctrine (which required radio and TV stations to “program in the public interest,” a phrase that was interpreted by the FCC to mean hourly genuine news on radio and quality prime-time news on TV, plus a chance for “opposing points of view” rebuttals when station owners offered on-air editorials), and then in 1996 President Bill Clinton signed the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which eliminated most media-monopoly ownership rules. That same year, billionaire Rupert Murdoch started Fox News, an enterprise that would lose hundreds of millions in its first few years but would grow into a powerhouse on behalf of the monopolists.

From Reagan’s inauguration speech in 1981 to this day, the single and consistent message heard, read, and seen on conservative media, from magazines to talk radio to Fox, is that government is the cause of our problems, not the solution. “Big government” is consistently—more consistently than any other meme or theme—said to be the very worst thing that could happen to America or its people, and after a few decades, many Americans came to believe it. Reagan scare-mongered from a presidential podium in 1986 that “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the government and I’m here to help.”

Once the bond between people and their government was broken, the next steps were straightforward: Reconfigure the economy to work largely for the corporate and rich, reconfigure the criminal justice system to give white-collar criminals a break while hyper-punishing working-class people of all backgrounds, and reconfigure the electoral systems to ensure that conservatives get reelected.

Then use all of that to push deregulation so that they can quickly consolidate into monopolies or oligopolies.

Government as a Monopoly?

The core argument of the “government is bad” crowd is that government is, itself, a monopoly. Since everybody knows that monopolies are bad things, so, too, government must be an intolerable affront that reduces the quality of life for its citizens. This meme has been incredibly destructive to America’s working people, who’ve become hostile to government while losing their wariness of corporate monopoly.

There’s one type of monopoly that’s actually good, with a single caveat. That’s called a “natural monopoly,” and for it to work properly, it generally requires government. Consider your home. While you can buy a new stove or sofa or rug from many different companies, you’ll be hard-pressed to buy your water, electric, or septic from more than one single vendor. There’s only one power line, water line, and sewer line attached to your home. Thus, power, water, and septic are generally referred to as “natural monopolies.”

To provide the best and most reliable service at the lowest price, communities across America have opted to have public (government) ownership of these utilities. Publicly owned electric companies, for example, provide power for about 15% less than privately owned for-profit power corporations, and they do so with an average of 59 minutes of service loss per year compared with 133 minutes of lost power from for-profit companies.44

While public power systems saw a huge growth spurt through the 1930s (with the help of New Deal programs building huge dams and starting the Tennessee Valley Authority), ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s, the tide turned as a neoliberal (deregulated or laissez-faire capitalism) privatization craze crept across the American landscape in a big way following the election of Reagan in 1980.

Today, only one in seven households gets its power from publicly owned companies; the rest of us are paying the extra 15% for corporate profits and shareholder dividends, and living with more outages because for-profit companies are paying dividends instead of maintaining their equipment.

This turned deadly in 2018 when wildfires erupted across California, a significant number of which were started by poorly maintained Pacific Gas & Electric power lines. Their quest for ever-increasing profits literally killed people.

As the July 10, 2019, headline and subhead in the Wall Street Journal noted: “PG&E Knew for Years Its Lines Could Spark Wildfires, and Didn’t Fix Them: Documents obtained by the Wall Street Journal show that the utility has long been aware that parts of its 18,500-mile transmission system were dangerously outdated.”45

PG&E took money devoted to updating their systems and instead passed it along to their shareholders and executives. Judge William Alsup, supervising PG&E’s probation for killing eight people in a 2010 gas pipeline explosion, noted that “PG&E pumped out $4.5 billion in dividends and let the tree [trimming] budget wither.” The result was a series of deadly wildfires caused by downed power lines, like the Camp Fire of 2018 that destroyed 14,000 homes and killed 85 people.46

Just after that 2010 explosion, it was revealed that PG&E had taken roughly $100 million that was earmarked for safety upgrades and instead distributed it, in part, to its senior executives.47

With the economic power derived from control of a natural monopoly, private power companies started flexing their political muscles. The legislature of Hawaii, for example, the only state to get its electricity entirely from private power companies, allows those companies to heavily penalize their customers who try to put solar on their homes or businesses.

The Hawaiian utility began rigorously enforcing their ability to punish solar-installing customers during the George W. Bush administration, and Scientific American magazine noted, “Since the Oahu rule went into effect three months ago, it has hurt business and ‘deflated the movement,’ [Charles] Wang [owner of a small Hawaiian solar-installation company] said. The rule led to a 50 percent drop in business in this quarter at many solar installers, according to interviews with many in Hawaii’s solar industry.”48

The article added that in 2007 there were more than 300 solar installation companies in the state, but by 2013 the number was down to “just a few dozen.” Nichola Groom, the article’s author, noted, “R&R Solar Supply, a 25-year-old distributor of solar panels to installers statewide, recently rented nine 40-foot containers to store panels meant to go on Hawaiian rooftops in the fourth quarter—typically the industry’s busiest time of year. Its Honolulu warehouse is ‘packed to the gills,’ said Chief Executive Officer Rolf Christ, adding his panel business is down 50 percent.”49

Natural monopolies in the hands of corporate hustlers are so ripe for exploitation that most states regulate the private utilities just to keep their citizens from getting repeatedly taken advantage of. And so citizens end up paying for our government to maintain a separate regulatory apparatus just to protect its citizens from rapacious private utility executives, plus paying those executives millions a year, plus a large slice of the action going to stockholders. One wonders why any community in America would go for these kinds of companies, particularly when Europe is running pell-mell toward ditching its private utilities for state-owned enterprises.

Germany is at the forefront of the movement toward remunicipalization, with the Transnational Institute highlighting, in 2018, 347 of the 835 Europe-wide examples of utilities being clawed back from private and into public hands happening in that country. Two hundred and eighty-four of them were in the energy sector.50

The thing preventing America’s recovery from the international experiment with privatization during the period from 1980 to 2010 has largely been the US Supreme Court, starting with its Buckley v. Valeo and First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti rulings in 1976 and 1978, respectively (see The Hidden History of the Supreme Court), and most recently Citizens United v. FEC, that for-profit companies and the billionaires they produce can pour unlimited amounts of money into the campaigns of the politicians that we, uniquely among developed nations, allow them to own.

Now, the same people who trust their government to correctly execute criminals, deliver their mail, and route their airline’s flight safely home, as the result of Reagan’s rhetoric and decades of “think tank” spokespeople appearing daily on TV and radio news shows, no longer trust government when it comes to regulating the oil and gas industry or protecting coal miners. They trust their government to get them their Social Security or tax refund check but don’t think state or local governments can successfully run natural monopolies.

Commons vs. Private

Reagan’s “starve the beast” strategy has been used for nearly 50 years to shrink government until it no longer works well and then point to that failure to justify privatization.

Trump most recently reduced the workforces of Social Security, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Internal Revenue Service (IRA) by tens of thousands as his contribution to starving the “beast” of government: the result is that it can now take two years for Social Security to process a disability claim; the EPA is virtually impotent against corporate polluters; the USDA is letting factory farms “self regulate,” producing a nationwide explosion of food poisoning; and the IRS has largely stopped conducting large, multiyear audits of wealthy people, focusing instead on cheaper and faster audits of average working people—all while private tax-preparing companies’ efforts to prevent the IRS from offering free tax services got a huge boost.

The rationale for “starve the beast” is that when things are done by private industry, they’re “more efficient” and “better done” than when done by government.

I lived in Germany, right near the East-West border, in the 1980s and remember well the Trabbies, these awful little three-cylinder, two-stroke, four-passenger cars that the communist government of East Germany manufactured for its citizens. They were terrible—stinky, unreliable, and dangerous.

I don’t want my car made by the government. Nor my computer, nor my clothes.

On the other hand, when we look at how Enron handled electric service in multiple states, or how Comcast and other big ISPs treat their customers, or the horrors of the private student loan industry, it’s pretty hard to think that we want private industry running anything that includes the commons.

Which raises the core questions in this debate: What is the commons? Where does it begin and end?

The answers to those questions go a long way toward revealing where a person sits on the economic/political spectrum.

Those who think that the commons should be very, very narrowly defined tend to be libertarians and conservative Republicans. It’s fine, in their minds, for government to take care of basic police and army functions, but even the fire department or interstate highway being publicly owned instead of being a profit center for a capitalist is a stretch too far. On the other end of the spectrum are communist governments like those in Vietnam and Cuba, where the government owns or supervises even most manufacturing and retailing (although both countries are experimenting with limited free enterprise). In the middle are most developed countries today, what many of them call democratic socialism.

In this system with both a mixed government and a mixed economy, the commons are broadly defined as those areas of the physical and economic landscape where there’s broad general ownership and a large impact on the quality of life of most citizens.

Thus, a democratic socialist state would argue that water and electric are part of the commons because they’re “natural monopolies,” things that are hard to run competitively. We have only one water line and one electric line coming into our homes, so competition is pretty much out of the picture; turning them both over to local government, accountable to the consumers rather than distant stockholders, only makes sense.

And, indeed, across the nation, utilities that are owned and run by the government generally have a much better record of safety, service, and reasonable pricing than do privately owned utilities.

Democratic socialists extend this logic to health care and, in some cases, banking. If everybody in the country is paying for everybody else’s health care via their taxes, the entire society has an incentive to behave in healthy ways. In Denmark, bicycling is so aggressively encouraged (to reduce the nation’s health care costs) that about half the total traffic in Copenhagen on any given day is made up of individuals on their bikes.

In most European states and in Australia, for example, the social pressures to quit smoking come from people concerned about the public health, but also from people who know that every smoker’s cancer is going to cost their society a half-million dollars, a portion of which will come out of their taxes.

Many of these nations even regulate their food supplies to discourage the consumption of obesogens (compounds contributing to obesity) like high-fructose corn syrup and some of the hormone-interrupting compounds that are used as flame retardants, as liners of tin and aluminum cans, as plasticizers, and to make carryout-food paper trays and coffee cups waterproof.

The problem with these types of democratic socialist systems, from the point of view of libertarians and conservatives, is twofold: First, they don’t philosophically fit in because they’re “big government” solutions, and anything that makes government bigger is, in their minds, an intrinsic evil. Second, no good capitalist is making money on any of the commons, and that’s intolerable because, they say, capitalism when applied to the commons will make the commons function better due to “market forces” and “the invisible hand.”

But comparing the American health care system with that of any other of the 34 OECD “most developed countries” in the world gives the lie to the libertarian line. Every other developed country in the world has some sort of universal health care program, and all of them deliver health care as good as or better than America’s, at anywhere from two-thirds to half the cost of what Americans pay.

When the commons are sliced and diced by private enterprise, the result is almost always a true “tragedy of the commons” (to quote ecologist Garrett Hardin): exploitation, monopoly, and price gouging.

Whether in a nation’s schools, its utilities, its prisons, its public roads, or even its internet access, when these core parts of the commons are privatized and then ring-fenced by private enterprise, somebody is going to get rich, and the majority of the people will be poorer.

Libertarians Object

Libertarians and their fellow travelers, however, deny that such natural monopolies even exist.

“There is no evidence at all that at the outset of public-utility regulation there existed any such phenomenon as a ‘natural monopoly,’ ” wrote Thomas J. DiLorenzo for the Review of Austrian Economics.51 He opened the article, in fact, with an even bolder statement by libertarian apologist Murray Roth-bard: “The very term ‘public utility’ . . . is an absurd one.”

Libertarianism was invented in 1946 by a think tank organized to advance the interests of very big business, the Foundation for Economic Education. FEE’s project was to provide a pseudoscientific and pseudoeconomic rationale for business’s attacks on government regulation, particularly government “interfering” in “markets” by protecting organized labor’s right to form a union. They invented the libertarian movement out of whole cloth to accomplish this.

FEE was founded in 1946 by Donaldson Brown, a member of the boards of directors of General Motors and DuPont, along with his friend Leonard Read, a senior US Chamber of Commerce executive (and failed businessman).

In 1950, the US House Select Committee on Lobbying Activities, sometimes called the Buchanan Committee after its chairman, Representative Frank Buchanan, D-Pa., found that FEE was funded by the nation’s three largest oil companies, US Steel, the Big Three automakers, the three largest retailers in the country, the nation’s largest chemical companies, and other industrial and banking giants like GE, Eli Lilly, and Merrill Lynch.

As reporter Mark Ames found when researching the Buchanan Committee’s activities, FEE’s board of directors included Robert Welch, who would go on to found the John Birch Society with help from Fred Koch, along with a well-known racist and anti-Semite, J. Reuben Clark, and Herb Cornuelle, who was also on the board of United Fruit (which was then running operations against working and indigenous people in Hawaii and Central America).52

The Buchanan Committee also discovered that an obscure University of Chicago economist, Milton Friedman, was working as a paid shill for the real estate industry. He was hired through FEE to come up with and publicize “economic” reasons for ending rent price controls, commonly known as rent control. The public good didn’t matter, Friedman concluded; all that mattered was the ability of businessmen to work in a “free market”—free of any substantive obligation to anything other than their own profits.

The Buchanan Committee knew what it had found. It reported the following:

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the Foundation for Economic Education exerts, or at least expects to exert, a considerable influence on national legislative policy. . . . It is equally difficult to imagine that the nation’s largest corporations would subsidize the entire venture if they did not anticipate that it would pay solid, long-range legislative dividends.

As Ames notes and the committee uncovered, “ ‘Libertarianism’ was a project of the corporate lobby world, launched as a big business ‘ideology’ in 1946 by the US Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers.”53

The man financing much of this, Herbert Nelson, head of the real estate lobby, didn’t think that democracy was even particularly useful, especially if it interfered with the ability of very wealthy people and big corporations to control both markets and the nation. As Nelson wrote, and the committee revealed, “I do not believe in democracy. I think it stinks. I don’t think anybody except direct taxpayers should be allowed to vote.”

In that, Nelson was simply echoing the perspective of many of the conservative movement’s most influential thinkers, from Ayn Rand to Phyllis Schlafly. Ask any objectivist (follower of Ayn Rand) or true libertarian, and they’ll tell you up front: the markets, not voters in a democracy, should determine the fate and future of a nation.

As Stephen Moore, whom Donald Trump tried to nominate to the Federal Reserve, told me on my radio program during the Bush years, he considers capitalism more important than democracy. There’s only one power on earth that can successfully take on monopolists who want to dominate not only a nation’s markets but its politics as well: government. Only We the People can challenge the power of massive, aggregated wealth and the political power it carries.

That’s why libertarians and their libertarian-influenced Republican allies constantly rail against government. As Reagan said in his 1981 inaugural address: “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” And if you own a major oil refinery that’s facing huge fines for polluting and causing cancers and don’t want to spend the money to clean it up, that’s true.

Using libertarian theory and theology, big business now has an army of true believers, ready to join the newest billionaire-funded Tea Party to complain about things like health and safety regulations by calling them “government health insurance” and “government interference.”

Meanwhile, it’s now fashionable for tech billionaires to call themselves libertarians.54

The New Feudalism

The war for the heart and soul of America, funded by libertarian billionaires, has moved into the press, the internet, and our political arena. In that struggle, it’s more accurate to portray libertarians as “feudalists” than as advocates of anything new.

Feudalism doesn’t exclusively refer to a point in time or history when streets were filled with mud and people lived as peasants. More broadly, it refers to an economic and political system, just like democracy or communism or socialism or theocracy.

The biggest difference is that instead of power being held by the people, the government, or the church, those who own property and the other necessities of life hold power. At its essential core, feudalism could be defined as “government of, by, and for the rich.”55

Marc Bloch is one of the great 20th-century scholars of the feudal history of Europe. In his book Feudal Society, he points out that in almost every case, with both European feudalism and feudalism in China, South America, and Japan, “feudalism coincided with a profound weakening of the State, particularly in its protective capacity.”56

Given most accepted definitions of feudalism, feudal societies can’t emerge in nations with a strong social safety net and a proactive government. But when the wealthiest in a society seize government and then weaken it so that it can’t represent the interests of the people, the transition has begun into a new era of feudalism. “European feudalism should therefore be seen as the outcome of the dissolution of older societies,” Bloch says.

Whether the power and wealth agent that takes the place of government is a local baron, lord, king, or corporation, if it has greater power in the lives of individuals than does a representative government, the nation has dissolved into feudalism.

Bluntly, Bloch states, “The feudal system meant the rigorous economic subjection of a host of humble folk to a few powerful men.”57 This doesn’t mean the end of government but, instead, the subordination of government to the interests of the feudal lords. Interestingly, even in feudal Europe, Bloch points out, “[t]he concept of the State never absolutely disappeared, and where it retained the most vitality men continued to call themselves ‘free.’ ”58

The transition from a governmental society to a feudal one is marked by the rapid accumulation of power and wealth in a few hands, with a corresponding reduction in the power and responsibilities of government. Once the rich and powerful gain control of the government, they turn it upon itself, usually first radically reducing their own taxes, while raising taxes on the middle class and poor. Says Bloch: “Nobles need not pay taille [taxes].”

Bringing this to today, consider that in 1982, just before the first Reagan-Bush “supply side” tax cut, the average wealth of the Forbes 400 was $200 million. Just four years later, their average wealth had more than doubled to over $500 million each, aided by massive tax cuts.

Today, as the Institute for Policy Studies notes, “With a combined worth of $2.34 trillion, the Forbes 400 [individuals] own more wealth than the bottom 61 percent of the country combined, a staggering 194 million people.”59 Forbes magazine, for 2017, reported, “The minimum net worth to make The Forbes 400 list of richest Americans is now a record $2 billion. . . . [T]he average net worth rose to $6.7 billion.”60

While the Forbes 400 richest Americans have gone from an average wealth of $200 million in 1982 to over $6 billion today, the average wealth of working Americans stayed flat, in the face of explosions in the costs of health, education, and housing.

Median household wealth in 2013, for example, was $81,000—about the same as in 1983 (the first year of household wealth surveys by the federal government).61 But the median price of a house in 1983—around $74,000 (or $180,000 in today’s dollars62)—has, according to the US Census Bureau, risen to over $220,000 today (and it’s massively higher in most cities).63 In 1983, the average person working a minimum wage job could afford a college education; now there’s over $1.7 trillion in student debt.

And in 2017, Trump and his GOP doubled down on their plan to move America from democracy to feudal oligarchy by cutting more than $1.5 trillion in taxes, most of the cuts directed to the uber-rich and giant monopolistic corporations. As a result, massive companies like Amazon, Chevron, General Motors, Delta, Halliburton, and IBM paid nothing in federal income taxes the next year.

In every sector of our economy, big businesses have been concentrating power since the 1980s, and America’s once-strong middle class has been crushed under their heels.

From Route 66 to Anytown, USA

While the cancerous growth of giant corporate monopolies and oligopolies was largely held in check from the time of FDR until the Reagan administration, America’s middle class began to feel the influence of the laissez-faire Chicago School of Economics and Robert Bork in the last years of Nixon’s presidency. During Nixon’s era, when the US economy was about a third the size it is now, there were about twice as many publicly traded companies as there are today.

Public companies began to collapse in earnest in the mid-1990s, as the Clinton administration embraced neoliberal economics and maintained Reagan’s policy of not seriously enforcing the Sherman Antitrust Act. In 1996, there were roughly 8,000 publicly traded companies; today it’s in the neighborhood of 4,000.64

In my lifetime, America has transformed from a nation of small and local family businesses into a nation of functional monopolies where small handfuls, typically three to five giant companies, control around 80% of pretty much every industry and marketplace, and make pricing and other decisions in concert with each other.

We see this clearly in industries like airlines and pharmaceuticals, but it exists in pretty much every industry in America of any consequence. It’s often obscured, because companies operate under dozens or even hundreds of brand names, and they rarely list on their packaging or advertising the name of the corporate behemoth that owns them.

As Jonathan Tepper pointed out in The Myth of Capitalism, fully 90% of the beer that Americans drink is controlled by two companies.65 Air travel is mostly controlled by four companies, and over half of the nation’s banking is done by five banks. In multiple states there are only one or two health insurance companies, high-speed internet is in a near-monopoly state virtually everywhere in America (75% of us can “choose” only one company), and three companies control around three-quarters of the entire pesticide and seed markets. The vast majority of radio and TV stations in the country are owned by a small handful of companies, and the internet is dominated by Google and Facebook.

Right now, 10 giant corporations control, either directly or indirectly, virtually every consumer product we buy. Kraft, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Nestlé, Procter & Gamble, General Mills, Kellogg’s, Mars, Unilever, and Johnson & Johnson together have a stranglehold on the American consumer. You can pick just about any industry in America and see the same monopolistic characteristics.

A study published in November 2018 by Jan De Loecker, Jan Eeckhout, and Gabriel Unger showed that as companies have gotten bigger and bigger, squashing their small and medium-sized competitors, they’ve used their increased market power to fatten their own bottom lines rather than develop new products or do things helpful to their communities or employees. Much of this shows up in increased profit margins, the benefits of which are passed along to shareholders and executives, rather than consumers.

They note that, “while aggregate markups were more or less stable between 1955 and 1980, there has been a steady rise since 1980, from 21% above cost to 61% above cost in 2016.”

Markups (the price charged above production costs), they note, were fairly constant between the 1950s and the 1980s, but there was a sharp increase starting in 1980. Thus, they conclude, “[i]n 2016, the average markup charged is 61% over marginal cost, compared to 21% in 1980.”

Markups, of course, define what’ll be left over for profits and dividends.

Additionally, everywhere the size of companies and the domination of the market have increased, so have markups.66

For most of the history of our nation—and even the centuries before the American Revolution—one dimension of “the American Dream” was to start a small local business like a cleaners, clothing store, hotel, restaurant, hardware store, or theater, and then not only run it for the rest of your life but be able to pass it along to your children and grandchildren.

The first four years of the 1960s saw a new TV show—first in black-and-white and then in color—starring Martin Milner and George Maharis. The two drove on the nation’s most well-known highway, Route 66, every week, stopping in small towns and mixing it up with the locals.

In the trailer for the classic DVD set of the show, Maharis asks Milner, “How many guys do you know that have knocked around as much as we have, and still made it pay?”

“Oh, we sure make it pay,” Milner replies. “Almost lynched in Gareth, drowned in Grand Isle, and beat up in New Orleans . ..

I still remember being fascinated as a nine-year-old by the geographic, cultural, and linguistic diversity of the towns they visited across my nation. Every town was unique and was generally identified by the local businesses, which often provided a job for a few days for Tod and Buz.

Today, by contrast, you could be dropped from an airplane from a few miles up and land in any city in America unable to figure out where you were. Instead of the Peoria Diner, it’s Olive Garden or Ruby Tuesday. Instead of the Lansing Hotel, it’s the Marriott. Instead of local stores named after local families, it’s a few chains we all recognize or Amazon who’s providing the goods Americans want.

And as industries become more and more consolidated, the predictable result is that profit margins increase, prices increase, and the quality of products and services declines. We see this most obviously in the quality of services and products from internet service providers and airlines, but it even applies to industries as eclectic as hospitals.

In 2012, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation did an exhaustive review of studies on what’s happened in the hospital business as hospitals have undergone a rapid period of consolidation since the 1990s. They concluded that the results were higher prices and stable or reduced quality of care without any reduction in costs, and that in the parts of the country where hospitals had not consolidated, care was better than in areas where it had. They found this was true of both the US and UK hospital marketplaces.67

But didn’t we outlaw functional monopolies like this with the Sherman Antitrust Act back in 1890? And if so, what was the legal rationale for all this consolidation, and what did it have to do with Robert Bork?

The Borking of America

In 40 short years, America has devolved from being a relatively open market economy and a functioning democracy into a largely monopolistic economy and a monopolist-friendly political system. One of the principal architects of that transformation was Robert Bork.

Most Americans, if they remember Robert Bork at all, remember him as the guy who railed against homosexuality and “forced integration” in such extreme language that his nomination to the Supreme Court by Ronald Reagan had to be withdrawn. But Bork’s most important effort—one he worked on for more than 15 years nearly full-time—was in reshaping the business landscape of this country.

Attending the University of Chicago, Bork took a class in antitrust from an acolyte of Milton Friedman’s, Aaron Director. Bork described the class as a “religious conversion” that changed his “entire view of the world.”68 After graduation, he continued working with Director as a research associate for Director’s “Antitrust Project” and repeatedly gushed about Director in his book The Antitrust Paradox, which is credited (at least by Wikipedia) for nearly singlehandedly changing America’s antitrust laws.

When, in the 1970s, Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet’s private police force and army were taking democracy advocates up in helicopters and dropping them out from 3,000 feet over the Atlantic, Milton Friedman and his Chicago School boys enthusiastically signed up to help “reinvent” his economy. (A bizarre article in the libertarian magazine Reason argued, “Yes, it’s true—Friedman gave advice to Pinochet. But it wasn’t about how to find the best place at sea to dump the bodies of murdered political enemies.”69)

When the Soviet Union fell in the 1990s, Friedman’s men advised Russia on how to privatize its economy, doing so in a way that predictably produced both oligarchy and monopoly.

As long as Pinochet privatized Chile’s social security system for the benefit of that country’s bankers, and Russia sold off state-owned property to increase “privately owned wealth,” it was all good with Friedman and most of his associates.70

Bork argued, in one of the most influential essays (and, later, a book) of the 20th century, that the role of government relative to monopoly wasn’t to prevent any single company from getting so large that it could crush any competitor and capture the government that was meant to regulate it. The role of antimonopoly regulation was definitely not, he reasoned, even to promote competition.

It was, instead, all about “consumer welfare,” a term that he had brought into common usage and the Chicago School boys quickly picked up. In essence, he argued, it didn’t matter where a product was produced or sold, or by whom; all that mattered was the price the consumer paid. As long as that price was low, all was good with the world.

It sounded so Ralph Nader-ish.

Bork was a brilliant writer and used vivid imagery to make his points. “Anti-free-market forces now have the upper hand and are steadily broadening and consolidating their victory,” he wrote in “The Crisis in Antitrust,” published in 1965 in the Columbia Law Review and cowritten with Ward S. Bowman Jr.71 They “threaten within the foreseeable future to destroy the antitrust laws as guarantors of a competitive economy.”

Having staked out his position as the advocate of antitrust, he noted that the forces that he opposed had a “real hostility toward the free market,” which could be found “in the courts, in the governmental enforcement agencies, and in the Congress.”

Since the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act, America’s political and judicial systems had embraced antitrust, Bork noted, so much so that in 1978 “they [antitrust doctrines] enjoy nearly universal acceptance,” although “these doctrines in their present form are inadequate theoretically and seriously disruptive when applied to practical business relationships. . ..

“One may begin to suspect that antitrust,” he wrote, “is less a science than an elaborate mythology, that it has operated for years on hearsay and legends rather than on reality.” In fact, Bork wrote, the entire notion of antitrust law as a vehicle to protect small and local businesses from large and national predators was a terrible mistake.