Identify Hidden Leaders

We have identified four facets of hidden leadership, with specific, observable behaviors that might indicate a hidden leader at work. The perfect and fully developed hidden leader displays all these behaviors. However, no one is a perfect specimen of any given characteristic. Everyone can be placed on a continuum of behaviors. How do you, as a manager, look at a person as a whole and identify potential as a hidden leader?

WHEN ONE CHARACTERISTIC IS MISSING

While, ideally, potential hidden leaders you have identified will exhibit integrity and some element of the remaining three aspects, you may notice people you think are leaders who are strong in only two aspects, or perhaps one. Without developing the missing characteristics, it is unlikely that hidden leaders will fulfill their potential. It’s similar to sitting on a three-legged stool with one short leg. No matter how good your balance, your stool will be weak in one direction. The same is true of hidden leaders.

This is not to say that, given demonstrated integrity and at least two characteristics, a hidden leader cannot be developed. But how can a manager know if a particular person has the potential for hidden leadership in spite of skill deficits?

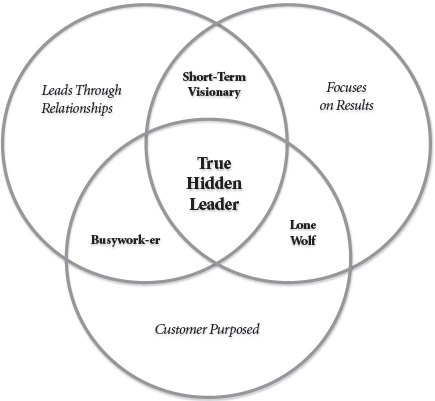

When two of the three characteristics are present, you will see distinctive roles and reputations in potential hidden leaders. We have identified them as the short-term visionary, the busywork-er, and the lone wolf (see Figure 2-1). Each of these types lacks one of the key characteristics of the true hidden leader.

Figure 2-1: Venn diagram of the varieties of hidden leadership, based on the three key characteristics.

By evaluating each potential hidden leader’s integrity and knowing how each person might respond to development and investment, a manager can identify the less-than-perfect hidden leaders in the organization who still can be coached to provide important leadership in the company.

Let’s see how you can identify potential hidden leaders who are missing one of the three key characteristics of the true hidden leader.

The short-term visionary combines results and relationships to produce action. Generally, these workers are effective in getting things done—at least things relevant to the short-term success of the company. They are continually in achievement mode, clicking off tasks, completing assignments, and accomplishing goals, all while keeping relationships intact.

However, the short-term visionary is missing the customer-purposed characteristics of a true hidden leader. This frequently leads to actions that produce short-term gains at the expense of long-term results.

Because they are not customer purposed, these potential hidden leaders lack the voice of the customer in their actions. As a result, they are in danger of making decisions that address localized, internal issues at the expense of customers.

For instance, a desk clerk at a hotel may choose not to make a concession for a frequent guest, with the idea of saving the company money. Doing so improves the organization’s profitability, at least for that night. Because the clerk authentically built a comfortable relationship with the night’s customer and put no internal relationships at risk, she may be seen as a good team player because she makes decisions based on the internal goals of the business. But by not recognizing an opportunity to act with the customer in mind, she may have also sacrificed an opportunity to build that customer’s long-term loyalty and, with it, the organization’s profitability beyond one night.

Some of these customer-purposed decisions are enabled or hampered by the policies of the company itself. For example, some hotel chains do not give their clerks (or managers) any flexibility with rates or special requests. In those cases, to expect that a hidden leader would act with the customer in mind—and still have a job after a few instances of breaking the rules—is wishful thinking on the part of the organization’s management. If you as a manager see many short-term visionaries around you, all trying to do a great job, you may consider looking at the policies and procedures that inhibit these people’s abilities to blossom into full-fledged hidden leaders by being customer purposed.

The hospitality world includes one company that is cognizant of every employee’s ability to be customer purposed in the right situation. The Ritz-Carlton hotel chain is famous for its customer-purposed culture. Every person, including those on the housekeeping staff, receives intensive training, development, and encouragement from all levels of management to provide the customer service for which the company is famous.

One policy in place throughout the hotel chain is that each employee, including housekeeping staff (we refer to housekeeping again because, for some reason, many people do not consider them important to the customer’s experience of a hotel), is authorized to spend up to $50 a night of the hotel’s money on any overnight guest to create an experience that makes for a happy customer. It may entail replacing a ruined shirt, or buying shoes to stand in for ones forgotten at home. The policy is whatever it takes—and the freedom to spend $50, no questions asked. That is a policy that enables hidden leaders to act on their customer-purposed instincts.

Without customer purpose present, eventually, the short-term visionary, effective as he may be in the moment, misses the big picture. In doing so, he cannot act out the value promise of the organization.

We don’t imply that short-term results aren’t critical to any organization. As we aim for the long term, it is short-term success that gets us there. No company can reach its long-term markers of success without passing the short-term markers along the way. But failing to meet customer objectives at the same time makes ever reaching our long-term objectives nearly impossible.

When you as a manager see short-term visionaries, remember that a customer-purposed attitude can be developed. Do not discount the importance of people with strong relationships throughout the organization and an ability to focus on results.

Have you ever noticed an employee who is incredibly busy but seems to contribute very little to the company’s long-term success? These well-intended professionals frequently have good relationships and exhibit a strong customer purpose. They certainly display a good work ethic, and they do get things done, especially routine assignments or marginally important projects. But without a focus on results, odds are that these workers will accomplish very little that contributes much to the value desired by customers or the long-term health of the organization. We call these potential leaders busywork-ers.

The busywork-er lacks the characteristic of a focus on results. Without that focus, the person has no yardstick by which to measure the importance of specific tasks. Many busywork-ers have tremendous planning and execution skills, as well as excellent relationships. They do maintain the centrality of the customer, which helps them make tactical decisions. But without the end game in mind, they may expend energy on projects and ideas that are good but not as valuable as they might be to the organization or the customer. They get results, but the results may not be in line with the company’s strategic objectives.

Without a focus on results, the busywork-er risks having all of her work devolve to a task without aim. In other words, work for work’s sake. Sometimes, of course, certain work must be done, and done well and on time, that is important to the organization as a whole. But the busywork-er in that position who cannot evaluate based on a focus on results will not become a hidden leader.

For example, a human resources staff person may be a firm believer in the organization’s promise to customers and possess strong relationships across the organization. He has two of the important characteristics of a hidden leader. But without a focus on results, he often gets mired in tasks and overwhelmed by priorities. He has trouble determining which of many responsibilities actually contribute in a meaningful way to long-term business results. His ideas and suggestions often miss the mark in terms of driving the organization toward its strategic goals. Everyone likes him because of his strong relationships, but he is not often called on to brainstorm solutions to thorny issues that are critical to the company’s success.

Some of this evidence of a busywork-er—confused priorities or a lack of significant contribution—can also be created when an organization fails to either communicate the results desired or changes the end game frequently. If you see many busywork-ers among your staff or in your company, look critically at how upper management is communicating the results desired for the company. Does the C-level consistently change the strategic vision? Is the vision too vague to be translated into tactical goals? Do executives ignore the importance of communicating a strong vision to all levels of the organization? Is that communication tardy, unclear, a one-off event, or contrary to previous vision statements? If the answer to any of these questions is “yes,” your lack of hidden leaders and glut of busywork-ers may be a structural problem in your organization.

For example, before news sources commonly accepted the importance of an online presence, we worked with a large New England newspaper struggling to compete in a changing market. Key competitors had already taken a chunk out of the paper’s ad revenue through their websites. Some were local newspapers, but others were former or specialized ad sheets that catered to niche audiences.

The newspaper’s CEO assigned an online group to create a website that would recapture this ad revenue. But the CEO insisted that the site couldn’t take ads away from the printed product, nor could it upstage the paper with original stories. The CEO did not communicate or discuss a clear vision of what the website should be. Clearly, management saw the website as a second-tier stepchild of the newspaper.

Undaunted by this status, the team was enthusiastic. Said one team member, “We felt we were defining something new for the industry. But the goal set for us by management seemed contradictory: nothing new or free, but create ad revenue.

“We went around in circles. We had vision meetings, created slide decks of business models, and the programmers—we asked them for scores of sample pages, trying to find our product. We worked almost around the clock to meet internal deadlines. It wasn’t uncommon for meetings to be interrupted, or for programmers to take on competing priorities.

“In the end, we produced online access to the newspaper for existing subscribers, complete with firewall and passwords. But from the start, advertisers didn’t want to pay for online ads that already were in the newspaper, and subscribers tended to want the physical product, since the experience of the two was essentially the same. When traffic to the site dissolved, we were frustrated. All that work, and nothing, really, to show for it.”

Clearly, the CEO and other managers, struggling with falling revenues, did not see the website as a player in the process of regaining market share. They did not help develop or communicate a vision for what the website might be. In essence, without this support for its work, the team wasted time trying to discover a vision through trial and error. Team members had talent, skills, and enthusiasm. They lacked clear priorities and a vision supported by the overall goals of the newspaper. The result was a lot of busywork for people who could have contributed much more to the paper’s success.

The ability of a busywork-er to connect his work to specific company strategies, goals, and objectives would make a huge difference in his contributions to the company. It would also make that person an effective hidden leader. Fortunately, a focus on results can be learned. It does require structural support within the organization, but given that, managers can develop busywork-ers into hidden leaders with development and training.

We’ve seen that a focus on results is important to evaluate what work to get done. Being customer purposed provides another measure to ascertain what’s important for the success of the customer and the company. Absent the ability or interest to develop productive and positive relationships, however, a worker limits his success. We call a potential hidden leader who lacks the ability to lead through relationships a lone wolf.

In some situations, a lone wolf can be an asset. Especially where technical requirements are key, a lone wolf can accept an assignment, understand its importance, and do it well. Many people with specialized or concentrated knowledge in a variety of fields, from software development to finance to law to medicine, fall into this category and produce great work for a company. It may be the cornerstone of a product’s success. But lone wolves are unlikely to develop into hidden leaders.

Without support from others in an organization, it is difficult for anyone to provide effective leadership. Project work generally occurs horizontally in companies. That is, many projects involve different functions, often organized vertically, that rarely interact with one another. (Thus the term silos to describe such functions in an organization.) To lead effectively, a hidden leader must garner support across these silos and work with multiple constituencies among different functions in the organization. Lacking that ability, the hidden leader is reduced to a lone wolf: an effective and productive person but not someone considered to be a leader.

For example, a product-development associate in a manufacturing company may be gifted in her ability to understand and engineer solutions to customer problems. She may be very organized because she is so results oriented. But if she can’t cultivate positive relationships with others in her department or throughout the organization, she will be unlikely to collaborate with others. She may be capable, and pose good ideas, but lacking good relationships will limit her effectiveness. She is likely to miss out on insights and input from colleagues that could improve her work, or lose opportunities to see her hard work adopted by the organization.

The most common lone wolf behavior we’ve seen is that of the rogue sales professional. Generally, this person is very results focused and customer purposed and may achieve good sales results. But the customer is his primary target: He puts little effort or energy into developing relationships with colleagues.

Others in the organization complain that this person often doesn’t cooperate with marketing and has conflicts with people in accounting or product delivery. He tends to have more difficulty resolving organizational issues for customers in such areas as on-time delivery, product quality, or billing. He can also create problems in the organization that may increase costs. Compare these behaviors with those of salespeople who have effective relationships with other departments. Issues affecting their customers are resolved smoothly and with less organizational strain.

The irony here is that successful lone wolf salespeople have reasonable relationship-development skills; they simply do not aim them at their coworkers.

Absent connections through relationships, the lone wolf also makes work more difficult because he has trouble getting others to support even his best ideas. He may tend to work behind the scenes to get around committees, leaders, and task forces. This may build a reputation of being an outlier, especially if the lone wolf’s work is essentially strong. Then this person becomes someone to manage closely, not someone to see as a potential leader within the organization.

If you see lone wolves predominating in your organization, you may be seeing evidence of a cultural communications problem. How often do relationships devolve into backbiting or political struggles? How well are people acknowledged and commended publicly for their work? Who gets the credit when credit is due? How honest and forthright are C-level executives perceived to be? Answering these questions can help you determine if the only way to survive in your company’s culture is to be a lone wolf. In that case, managers will have trouble finding and developing hidden leaders because the culture does not value the importance of developing relationships.

For example, Scott was working with a venture-backed biotech start-up. Rapidly growing with new innovations, the company had increased its employee base tenfold in just two years. Executive management stated a key value as “mutual respect for each other.” A widely understood responsibility based on this value was that if someone experienced a problem with another person, it was the first person’s responsibility to try to work it out before taking the conflict to the next level of management.

This rule of responsibility was endemic in the culture. If someone discussed a personal conflict with a third person, the standard first response was, “Have you talked with the person about this?” If the answer was no, then without any gossip, the protocol was to simply suggest that action. The combination of practicing those two elements (not just giving lip service to them) created an environment that placed high value on developing constructive relationships, a massive enhancer of productivity.

At one point, the company ran into difficulty getting a new product to market. As critical deadlines passed, tensions ran high and some finger pointing began. After a particular series of problems, two frontline lab technicians volunteered to document the failure points in the project. Because these two techs had developed good relationships with colleagues in clinical marketing and R&D, they could gather information that otherwise would have been difficult to obtain. Recognizing this, people in other departments were willing to collaborate with them. The tone and tenor of these relationships enabled the techs—obviously two hidden leaders—to sort out disagreements and inconsistencies by seeking cause, not blame. Not only were the lab techs able to identify technical problems, communication breakdowns, and process glitches, they discovered new information that enabled them to recommend multiple ways to tackle the issues. Management adopted nearly every one of those suggestions.

Eight months later, the release of the new diagnostic product was tremendously successful. The company increased its revenue by more than 40 percent in the next two quarters. As a result of her efforts, one of the lab techs was offered a promotion to lab manager, which she accepted. The other, for personal reasons, declined a similar opportunity the following year. A few of her colleagues jokingly—but respectfully—refer to her as “first among equals.”

In most organizations, it takes more than one person to achieve an objective. In classical sales organizations, where individuals close sales without significant staff support, the collaboration of others helps sales professionals market, deliver, collect, and service accounts. No one can drive organizational success alone.

Sometimes technical brilliance is able to stand on its own. More often, though, it is a result of people working productively together to produce results. Without leading through relationships, a hidden leader cannot emerge.

WHEN ONE CHARACTERISTIC DOMINATES

In our experience, hidden leaders rarely display only one of the three characteristics of leading through relationships, focusing on results, and being customer purposed. However, there are times when one element predominates in how a person works in the organization.

When leading through relationships is all-important to a person, we see the “nice guy” emerge, the employee who may not have technical skills or a focus on results or the customer but whom everyone likes. Unfortunately, often these nice guys are shuffled around organizations because no one has the heart to demand better performance or let them go. We have worked with managers who agonize for months or years over what to do with these professionals because they like them as people but struggle with the amount of value they create for the organization.

One executive at a Fortune 500 computer hardware manufacturer told us that a particular nice guy in his organization was hard to release because he was so well connected and liked. The executive was concerned about the damage to his own reputation for terminating such a popular employee. Staff may like the nice guy in a management role, but often they must go around him to actually get things done.

A zealous focus on results creates a person we call a driver. While on the surface it seems an organization would love drivers, they can be very disruptive. In the short run, the driver may earn the respect of others, but such an employee will not be able to be a hidden leader.

On one coaching assignment, we were called in to work with a manager who was very successful at achieving most of the objectives put before her. She hit her numbers and attained budget targets. Unfortunately, as her manager put it, she wrought so much havoc among others in reaching those goals that many questioned whether she was worth the hassle.

Organizations value customer focus, but when being customer purposed is the primary characteristic of a worker, she is seen as a warrior. These individuals are often zealous advocates for clients and will do anything to satisfy a customer need or request—although some actions may be at the expense of doing what is right for the organization. In the worst cases, customer needs are used to push a specific agenda unrelated to what the customer truly wants.

We worked with one consumer packaged-goods company whose marketing group suffered greatly from this warrior syndrome. Many of marketing’s supervisors and managers were notorious for criticizing everything the organization did to help customers (except marketing of course). This attitude created rifts between marketing and other divisions. It drove a wedge between areas in the company that should have been allies in providing value to customers.

As a manager, should you try to convert the nice guys, drivers, and warriors into hidden leaders? Perhaps. Depending on your leadership needs and situation, some of these potential leaders may be worth the investment of training and coaching required to develop them into hidden leaders, especially if they are already in management ranks. For example, if a driver who is a manager has immense business savvy and vision critical to the company and is open to personal and professional growth, the investment to develop the person’s relational and customer-purpose skills may be worth it.

On the other hand, it is our experience that many more people lack only minimal critical characteristics to be hidden leaders. Some may lack one characteristic completely; others may have all three but may need development of two to a higher level of expertise. These are the potential hidden leaders from whose development you are more likely to get the most substantial return on investment.

The first facet of hidden leadership we discussed in this book was demonstrating integrity. It’s the context within which all hidden leaders—and many obvious leaders—operate.

In our view, there is no potential for a hidden leader who does not demonstrate integrity. This characteristic is observable, but trying to teach an adult integrity is attempting to counteract years of early training and self-awareness. We, like most managers, are not professional psychiatrists. Yet in our experience, it is not possible to train a person without integrity to develop and then regularly demonstrate integrity. Those who embrace a “certain moral flexibility” are not candidates for hidden leadership. Those who believe they can “get away with it” will continue to do so in spite of any training short of legal incarceration. We hope you as a manager don’t have to deal with that level of unethical behavior! It’s not the manager’s job to teach people how to improve their moral judgment. But it is the manager’s responsibility to help those with integrity develop the courage to demonstrate it. Employees who feel shy or intimidated or express concern privately can be coached to speak up in more public venues, like meetings. When they do, it’s the manager’s role to commend and support their efforts to demonstrate what they clearly embrace.

Many organizations claim integrity as a value. At issue is how they personify it. If integrity is endemic to the culture, it manifests itself in hidden leaders who demonstrate it consistently. It also emerges from positional leaders—managers, executives, and others—who have the courage to say, “This action is not in the best interests of our customer.”

On the other hand, there are organizations that say they embrace integrity but essentially mistrust their managers and supervisors to select people who fit into the organization’s culture. Many of these companies use so-called personality or psychometric tests as part of their hiring processes or as ways to build better communication skills among existing employees.

There are hosts of these tests, including Myers-Briggs, DiSC, and other “research-based” social-style tests and tools. Typically we see them used to label people and explain away bad behavior or poor skills. We’ve heard statements in these companies like, “Oh, he’s an ENTJ; what do you expect?”

We think this is simply lazy management. Further, we doubt the efficacy of the tests in telling anyone anything about their personalities. Seeing their results, test takers say, “Oh this is so like me!” Of course it is: They filled out the questionnaire. It doesn’t mean they will always respond that way, or that their personality is fixed in time and space.

Test results seem true because individuals look at them through the lens of their inner selves. They resemble astrology columns, which always apply to everyone’s vision of his day, no matter the sign. (Some such columns are invented by random people assigned to write them, like Laurie’s husband in his college days.)

Anne Murphy Paul, in her book The Cult of Personality Testing, agrees. She writes, “As many as three-quarters of test takers achieve a different personality type when tested again, and . . . the sixteen distinctive personality types described by the Myers-Briggs have no scientific basis whatsoever.”1 Using personality tests is a way to avoid the responsibility of selecting, hiring, or coaching employees so they can succeed in their jobs. It’s also a sign that integrity, however promoted, may be lacking in the culture as a whole.

WORKSHEET: EVALUATE A HIDDEN LEADER

The better you can pinpoint a hidden leader’s strengths, the easier it will be to develop missing skills and characteristics. Think of a specific person, and then review the pages that follow. Check the behaviors you have observed in all four areas: has integrity that shows, leads through relationships, focuses on results, and is customer purposed. The more checkmarks in each level, the more developed your hidden leader’s abilities. The online worksheet will calculate this for you.

Notice that when you evaluate integrity that shows, you are evaluating both the hidden leader’s ability to show integrity and others’ perception of that integrity. There are no levels of integrity per se, because there are no variations on integrity. One has integrity or not. In terms of evaluating the hidden leader, then, you are simply evaluating that leader’s ability to show the integrity that already exists within the leader’s personality.

EVALUATE A HIDDEN LEADER: HAS INTEGRITY THAT SHOWS

Description: Has the courage to consistently adhere to a strong ethical code, even in difficult situations.

Behaviors of the hidden leader

Observed Behaviors |

Evaluate: Yes or No |

Carefully evaluates before making promises that will be hard to fulfill |

|

Keeps commitments regularly |

|

Matches actions to verbal commitments |

|

Informs colleagues regularly about changing workloads or deadlines |

|

Consistently adheres to a strong personal ethical code |

|

Acts in accordance with company values |

|

Addresses potential ethical issues before they become major problems |

|

Makes ethical decisions consistently |

|

Speaks up when integrity issues are on the table, even if they are unpopular |

|

Describes both sides of an issue or argument |

|

Confronts others who act unethically or dishonestly |

|

Behaviors of the hidden leader’s colleagues

Observed Behaviors |

Evaluate: Yes or No |

Trusts the hidden leader to act in the best interests of the organization, its employees, and its customers |

|

Describes hidden leader’s treatment of others as fair and honest |

|

Models personal ethical behavior on that of the hidden leader |

|

Identifies the hidden leader as a good resource to help resolve disputes, clarify ambiguous situations, and address challenges |

|

Describes support from the hidden leader for efforts, accomplishments, and professional development |

|

EVALUATE A HIDDEN LEADER: LEADS THROUGH RELATIONSHIPS

Description:

• Uses interpersonal skills effectively

• Exercises a sense of curiosity

• Values others

• Believes in personal value to others, whether as a co-worker or as a friend

Observed Behaviors

Level 1 |

Level 2 |

Level 3 |

Level 4 |

|

|

|

|

EVALUATE A HIDDEN LEADER: A FOCUS ON RESULTS

Description: Uses the ends to define the means to achieve a goal, and maintains independent initiative to act.

Observed Behaviors

Level 1 |

Level 2 |

Level 3 |

Level 4 |

|

|

|

|

EVALUATE A HIDDEN LEADER: IS CUSTOMER PURPOSED

Description: Sees the big picture of the company’s value promise and acts in ways that enable that promise for the paying customer.

Observed Behaviors

Level 1 |

Level 2 |

Level 3 |

Level 4 |

|

|

|

|