Instill Customer Purpose

Customer purpose drives hidden leaders to see their work in light of the value it provides to the paying customer. It reaches beyond customer service to include the big picture facing an organization at any given point. Understanding the difference between customer purpose and customer service is your first step to building this skill in your employees. It’s also critical to know the sources of customer purpose and the ways it appears in terms of behaviors and attitudes. You can enable customer purpose in your employees by ensuring that they all understand the same definition of “customer” and can link the company’s value promise to their specific tasks.

CUSTOMER PURPOSE ISN’T CUSTOMER SERVICE

Executives like to believe that their organizations’ employees are focused on customer service. To a large extent, that may be true. Whenever employees in these companies face customer service problems, they work to address them. To support these efforts, many forward-thinking organizations’ R&D, marketing, or product-development departments research and identify specific customer needs. Then they design products or services that meet those needs and communicate the needs and solutions to those working directly with customers.

By its nature, customer service responds to customer needs. It isn’t completely passive, but a customer must be identified and a need declared before service can be offered.

There is nothing detrimental or necessarily easy about delivering excellent customer service. It is a critical aspect of a company’s performance. Customers are the reason that companies are in business. If a company cannot provide good customer service before, during, and after a sale, a big part of its value promise melts away.

In contrast, being customer purposed means proactively envisioning how any task affects the value provided to the customer by the company. It means being a visionary in the context of a specific job and with the company’s value promise in mind, as well as stated or potential needs of customers. Customer purpose creates value. Inside the organization, it translates into customer-focused processes, products, and services. From the outside, customer purpose builds a better customer experience. It strengthens a company’s business relationships with its customers, which is a distinct competitive advantage. Your competitors may be able to replicate products, services, and processes, but they cannot replicate a strong business relationship—especially if hidden leaders are the foundation of that relationship.

The best example we know of someone who was customer purposed wasn’t a hidden leader but a well-known world business leader and changer. When Apple presented the iPad to journalists in 2010, company cofounder Steve Jobs famously said, “It isn’t the consumers’ job to know what they want.”1 Jobs understood what it meant to be customer purposed: to know his customers so well he could think for them, create for them, and capture their imaginations and loyalty to his products. Everything Jobs did was about creating an extraordinary experience for his customers. It wasn’t about selling computers and electronic gizmos. It was about selling “cool.”

We see hidden leaders being customer purposed throughout organizations and in many businesses and fields. (Sadly, we see fewer top executives with the same characteristic.) Customer-purposed hidden leaders see their jobs in terms of the value their company provides, not in terms of the service or product the company is best at creating and selling. That value is often a perception that is created by the customer’s experience of a company.

The hidden leaders’ customer-purposed approach is evident from a number of observable characteristics. Some of these are evidence of good customer service, but not all great customer service people are also customer-purposed hidden leaders. The basics of being customer purposed extend past the skills of the most dedicated customer service professional.

For example, before a recent trip to New York with friends, Laurie booked a room at the Excelsior Hotel on the West Side to accommodate them all. She had never been to the Excelsior. When she walked in with her friends, Laurie was pleased by the Old World charm of the lobby and looked forward to enjoying the “room with a view” she had booked.

During check-in, the hotel clerk said, “By the way, we’ve upgraded you to a suite for your stay.” Laurie was surprised: As a first-time visitor, she had no relationship as a customer with the place. The suite was lovely and included the promised view, with more space for everyone. Laurie mentally resolved to use the Excelsior the next time she was in New York.

Was this standard policy, or initiative on the clerk’s part? Either way, it demonstrates a customer-purposed culture. Instead of upgrading only loyal customers, this clerk took it on himself to create a loyal customer with the upgrade. It cost the hotel nothing—the suite was empty for the two nights of Laurie’s stay—and it opened up a lower-priced room for potential future guests. Yes, this was a smart hotelier’s business decision. It was also the power of the organization’s customer-purposed policies in giving the clerk the option to make the decision, and building loyalty with a cost-free action.

Many companies strive to brand themselves so that all customers (including potential ones) experience value beginning at the level of seeing a logo. Fewer emphasize or train or reward employees on how their everyday acts on the job deliver the same value. Hidden leaders naturally understand this customer-purposed approach. From our perspective, it does more to support a successful brand than any marketing campaign.

Scott encountered this connection of brand and customer purpose when he took his daughter aquarium shopping at PetSmart. This organization’s vision is “to provide Total Lifetime Care to every pet, every parent, every time.” As Scott and his daughter eyed the fish tanks, a PetSmart associate stopped by. She talked with them about what they were looking for, what kind of fish they envisioned as a pet, where they would put the aquarium, and other aspects of fish ownership.

Because Scott knew next to nothing about fish, the associate could have eyed the equipment they selected and said, “Yes, buy all this and add X” to increase the sale and ensure the health of the fish. Instead, she said, “You will need these things, but not those things; get this instead.”

Scott had done some homework, so he knew his aquarium water had to be tested monthly. Dutifully, he had included an expensive water-testing kit. The associate said, “You don’t really need this. You’re setting up a small aquarium that won’t need daily checking.”

“But how do I test the water?” asked Scott.

“Just bring in a sample here, every month,” said the PetSmart person. “We’ll test it for you.”

This is more than good salesmanship or customer service. This is customer purpose, with a clear understanding of the company’s value promise and vision in mind. Selling Scott the water test kit would have increased the sale but not guaranteed the fish’s health, since Scott was not (yet) an experienced fish owner. Saving him that expense and offering to test the water provided better care for the fish and more opportunities to help Scott, his daughter, and the fish enjoy long and happy relationships. It was customer purpose.

THE SOURCE OF CUSTOMER PURPOSE

The source of being customer purposed is a deep understanding of the value promise of an organization. In organizations where the executive suite believes in communicating the true value promise organization-wide, hidden leaders can easily link their everyday actions to the company’s purpose. In those organizations that make no effort to help employees understand the value promise, customer-purposed hidden leaders make the effort to think through what the company is truly delivering to its customers—including future ones.

It’s helpful when an organization educates its employees on its value promise to customers. But when that is not the case, hidden leaders are able to be customer purposed because they engage five distinctive characteristics: enthusiasm for the work, balanced skill/communications proficiency, a sense of urgency, an owner’s mindset, and being champions of change.

When you talk with someone in a business context, how long does it take you to feel that person’s excitement and enthusiasm about work? Our audiences most commonly say it is about twenty to thirty seconds. That is how obvious it is that someone believes in the positive aspects of a job. This enthusiasm isn’t trained into an employee; no one can create authentic enthusiasm in someone else. It is a result of an organizational environment that supports employees, provides meaning, and links work to its values.

Without enthusiasm for the work, it’s difficult to build a customer’s trust. A lackadaisical or negative attitude decreases the customer’s confidence in a successful outcome and builds the customer’s resistance to anything the person might suggest as a solution.

Hidden leaders inherently show passion, energy, excitement, and enthusiasm for their work because they believe in the good it brings to the customer. This belief is self-generated by the hidden leader, although the organization may not have clearly considered and spelled out this good or value for its employees. When hidden leaders express this belief through a high level of energy and commitment, their customers’ confidence and trust increase. This eases conflicts and makes the customer more willing to explore alternatives because the customer knows that the hidden leader believes in the value of the work.

Enthusiasm born of a belief in the value to the customers drives hidden leaders to make the customers’ needs their purpose. This enthusiasm influences those around them, both colleagues and customers. Colleagues infected with enthusiasm provide better experiences for customers. Customers anticipate solutions and better service, which makes them approach interactions with more positive attitudes. They are more likely to purchase and continue to buy from your company and to tell others positive things about it.

As a manager, you may think it is easy to spot this enthusiasm in an employee. The enthusiasm of hidden leaders goes far beyond a can-do attitude. Hidden leaders convey excitement about getting the work done because of the value it brings to customers. They project this excitement with positive energy and enthusiasm specific to a customer’s situation, not simply in general. They consistently express confidence that the value the company provides to customers is significant and addresses important customer needs. They will also make an effort, in difficult customer situations, to stretch accepted policies and procedures in order to make the customer happy.

Enthusiasm for the work creates an energetic environment, which translates into improvements in products, processes, services, and culture. The result is increased productivity. This makes a huge difference for organizations and the bottom line in the short term.

Over longer terms, hidden leaders’ enthusiasm and energy encourage their colleagues’ loyalty toward and belief in their organizations. The resulting longer tenures ultimately can reduce turnover and related personnel expenses, which is a significant contribution to the bottom line. A 2012 report by the Center for American Progress claims an average of about 20 percent of annual salary is needed to replace workers. Lower-skilled workers are slightly less expensive, but for highly trained positions, such as nursing, executive, and technical jobs, the costs can add up to more than 200 percent of annual salary.2

Enthusiasm may seem like a lighthearted characteristic unimportant to the organization. But enthusiasm for the work, expressed by hidden leaders, is an important source of being customer purposed and an influence on a company’s profitability.

For example, we were helping a company that supplied capital equipment to major semiconductor corporations. Our task was to improve productivity and reduce time-to-market for new-product initiatives. The project involved a team of near equals in terms of title and tenure from the front lines of marketing, sales, manufacturing, procurement, and design.

Initially, when it came to directing the team, internal leaders seemed in short supply. The first few meetings were unfocused, and team members tended to point to other departments as the sources of delay and challenges.

Fortunately for the project, two hidden leaders stepped up and clearly took charge of the team’s efforts. They set agendas, made assignments, and promoted the importance of the team’s efforts for the company as a whole. Each was passionate about doing great work, and their positive energy inspired the others to buy into the process.

One of these hidden leaders talked about her excitement for the value she felt could be created with a successful project. The second focused on the overall process, shifting the team’s attention from pinpointing blame for problems to identifying causes of them and developing alternatives. These hidden leaders were obvious because of their energy and passion for improving productivity through excellence in their work.

Because of these hidden leaders’ actions, the team rallied behind them. Team members discovered that similar problems were emerging consistently in all new-product development; they concluded that the company’s standard process was inefficient. Together they redesigned the new-product workflow to integrate better interdepartmental communication and eliminate inefficiencies. Once implemented, the new process increased productivity and eliminated common issues that had emerged under the old system.

People need skills and abilities to do their jobs well. Without basic competence, there is little chance anyone will create value for a customer. But what are the skills that enable a hidden leader to be customer purposed?

Most jobs entail two distinct types of skills. One is the technical expertise to get the job done. The other is the ability to communicate effectively with the paying customer who benefits from the work or with the stakeholder involved in creating that benefit.

Technical expertise is usually relatively easy to evaluate because it entails a set of skills specific to the job. Accountants must manage numbers well, engineers need to know the specs of the materials with which they work, and customer service people need to know how the organization works so that customer problems can be addressed. It’s obvious fairly quickly if someone does not have the technical chops or experience to do the basic work of the job.

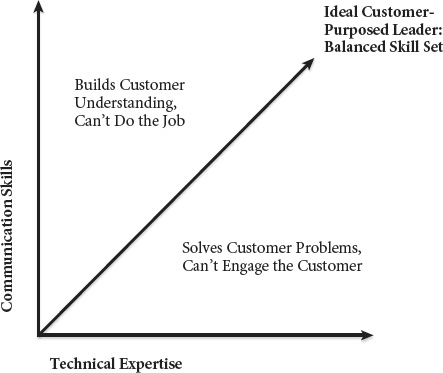

However, just knowing how to get the job done isn’t enough for a hidden leader to be customer purposed. It’s also important to be able to communicate with the customer or stakeholder about the process of doing the work (see Figure 6-1). Customer-purposed hidden leaders ask great questions, not just to uncover needs but to understand the issues from a customer’s point of view. They evaluate the customer’s or stakeholder’s level of knowledge about the problem and product or service and talk in language that makes sense and provides value. They do this without sounding like they are speaking down to customers and stakeholders, because they know that the person’s understanding is more important than the leader’s ability to sound smart.

Figure 6-1: Balanced technical and communication skills translate into proficiency to get the job done.

Being able to see how hidden leaders balance their skill proficiency can be daunting, especially if you are not in daily contact with them. Because hidden leaders balance their skills well, they may not ask for help constantly or need assistance from others. They do show strong technical competence at the skills required for the job; notably, when they lack the skills, they are not shy to ask for help from others. Similarly, they may have a reputation for having strong communication skills, or being able to calm distressed or upset customers and stakeholders. However, skilled communicators will ask for help when their skills are not sufficient to help a specific person. It’s the frequency and quality of the requests for assistance that can help a manager identify a hidden leader’s balance of skills.

Balancing technical expertise and excellent communication skills helps the hidden leader align work with customers’ needs and address the pertinent issues. This fine line between the two elements can be more important than being highly capable in either technical or communication skills alone.

For example, high technical expertise without communication effectiveness enables the leader to solve the problem, but without the engagement and cooperation of the other person, who may not understand the steps required to get the job done. Without sufficient technical expertise, the leader who communicates well may be able to engage the customer or stakeholder but may be unable to solve the person’s needs. Only when technical and communication skills are balanced can a hidden leader become customer purposed.

Since it is the balance of skills that creates proficiency, newly hired hidden leaders without high levels of technical and communication skills can create a positive experience for customers and stakeholders. Because these leaders’ approaches are based in integrity, they know when they need help with either technical or communication aspects of a relationship. They willingly engage others in the organization to help. At the same time, they tell customers and stakeholders exactly what is happening. Confidence is built not just on technical competence, but also on knowing what the leader is doing—and knowing that the leader accepts his or her own technical limitations without damaging the outcome for the customer or stakeholder.

Customer purpose requires a sense of urgency on the part of the hidden leader. But urgency is not speed. It is a commitment to act, to not stop until the customer’s needs are met. This sense of urgency—of believing that the customer’s needs are too important to ignore in the short or long term—is a driving force behind the hidden leader’s sense of being customer purposed.

Hidden leaders’ sense of urgency enables them to help other stakeholders see the importance of acting in the customer’s best interests and doing so swiftly. It provides the rationale for committing to action. Said differently, a sense of urgency provides the “why” behind the “what” of being customer purposed. When there is no immediate emergency to solve a customer’s problem, the sense of urgency drives customer purpose in everyday interactions with all customers and stakeholders.

For example, the ad-intake team in a printing company was assigned to implement a new set of quality assurance steps for the ad-intake process. It meant physically printing ads from digital files and comparing them to customers’ hard copies. Only then could the electronic files be sent to the compositors to insert into the final product. Team members were mostly ambivalent about the project. They saw it as additional work required for a variety of unrelated reasons, including management’s proclivity for “continual improvement,” and felt more comfortable with the status quo.

In contrast, one team member clearly felt a sense of urgency to get the new processes implemented. She knew that because of printer drivers in her company’s system, customers’ ads could look good on their equipment but not necessarily translate accurately in the printer’s compositor systems. The extra step would ensure that the digitalized ads would print as customers intended. This was clearly a benefit for their customers. A hidden leader, she knew she had to show team members the link of the “what” of these new processes to the underlying “why”: their impact on the customer. Otherwise, most team members would hesitate to commit to the project’s success.

To share and build this sense of urgency, this employee offered to hold several meetings to review the basis for the changes and the implications of not making them. By revealing unintended consequences and highlighting unforeseen problems, she helped the team see why the new quality control steps were critical to customer satisfaction. Outside of the meetings, she talked individually with some of the team’s members. She stressed the importance of their roles in the execution and completion of the project.

These actions helped the team as a whole develop a sense of urgency about integrating the new steps, which reflected a customer-purposed approach. The team became excited about adopting the process. Ad accuracy increased, fewer customer complaints resulted, and the project was a success.

A hidden leader’s sense of urgency translates into very different behavior than rushing to keep up with responsibilities. Because the urgency stems from the customer’s needs, hidden leaders work to maintain momentum when addressing those needs. That translates into good follow-up on customer and stakeholder requests. Beyond immediate customer contacts, the hidden leaders’ sense of urgency prompts them to raise the consequences of not taking actions for the customer when working with colleagues. Finally, hidden leaders strive to keep customers and stakeholders informed about what is happening behind the scenes, especially in terms of follow-up and contact outside of normal customer service requirements.

A sense of urgency isn’t primarily about avoiding problems or dodging negative issues concerning customers. Urgency is equally important to capitalize on market opportunities, address customer needs, and embrace chances to improve. Fear of loss and avoidance of pain can motivate action, but so, too, can desires for achievement, success, and innovation.

Some outside forces can create a sense of urgency. Earning business at a key client, beating a competitor to market with a new product, increasing engagement, improving service, or creating a culture of innovation are all positive organizational goals that can build a sense of urgency at a management level. That urgency is important, of course. But when hidden leaders express their own personal senses of urgency and influence others to feel the same, an organization stands a far greater likelihood of success.

Some very effective workers show up each day and tactically do their jobs, essentially trading their time for money. They handle their assigned responsibilities within the confines of minimal expectations. They are often seen as part of the backbone of an organization. They are rarely fired and are sometimes promoted. Essentially, they comply with getting the job done.

But hidden leaders bring much more to the workplace. They bring the commitment of a company owner to their jobs. Daily, they come to work ready to make a difference and help the organization and its customers achieve their goals. This customer purpose exists because hidden leaders see themselves as responsible owners of the organization, not just employees. They take ownership of their jobs and their companies’ success.

When a hidden leader acts like an owner, managers will see the leader reference company strategies in the process of making decisions in the workplace. These strategies will also appear as rationale by the hidden leader for arguments made in the customers’ best interests. Because customer-purposed hidden leaders take an owner’s perspective, they make it a point to understand how customers use the company’s products and services and, more important, why they use them. This understanding will also emerge in discussions about making strategic and tactical decisions within the company.

Additionally, a hidden leader takes responsibility for customer results and outcomes as if he or she were the owner of the company. He will often go outside the normal channels to provide for customers’ needs. This understanding and responsibility emerges because customer-purposed hidden leaders ask customers questions to understand their points of view. These questions cover more than the ostensible role of the company’s product or service. They go into areas that may not seem directly connected but help the hidden leader understand the context for the customer’s doing business with the organization. The leader translates this context to colleagues in the course of doing business, in discussions related to customers, stakeholders, products, services, and strategies.

Acting like an owner is strategic behavior that most senior executives would love to cultivate in their employees but often cannot see how to do. Behaving like an owner is not a subtle shift. It is a transformation that hidden leaders, with their self-ownership of actions, embody daily.

We all have our airport horror stories. But a few lucky travelers experience the opposite. One of our colleagues, a sales coach, was outbound on a weekend vacation trip. On the way to her gate at the airport, she paused to hear a salesperson’s pitch offering an airline credit card with travel benefits. The coach was interested in the card and decided to enroll. As the process got under way, she became engrossed in what she was observing: an experienced employee training a newcomer. She took particular interest because she was writing an article about sales reps learning from one another in the field.

With the pauses for training, the encounter took longer than expected. The sales coach, wrapped up in observing how the training was executed, missed the final call to board her flight. Realizing her mistake—and that her brief vacation was in jeopardy—the customer went to the airline’s service desk. (Luckily she was flying on the same airline that offered the credit card.)

Even though missing the flight was entirely the customer’s fault, upon hearing the tale of being caught up observing a training episode while enrolling in the company’s card program, the airline rep booked her on the next available flight at no charge. The rep even sent her to an alternate airport that would get the customer to her destination in time to use the ticket she had bought for a play that evening.

However, this meant the customer’s bag was at one airport and the customer was at another. At the arrival airport, another service rep, on hearing the tale of how a credit-card enrollment caused the traveler to become separated from her suitcase, arranged free delivery of the bag to her hotel.

What is noteworthy about this story is that the two hidden leaders focused on the customer’s overall experience with the airline, not just the transactions for which they were responsible—rebooking and baggage routing, respectively. Each representative acted in a matter of minutes, taking personal responsibility for creating a stellar customer experience without escalating the issue to a supervisor. For the customer, the memorable experience of a potential vacation tragedy averted by swift action developed a tremendous loyalty to that airline.

Hidden leaders embrace their organizations’ strategies—which, when successful, centralize customers naturally—as a daily operating template for how they define and do their jobs. This enables them to behave as if they owned the business. With an owner’s mindset, hidden leaders see their job’s importance to the company and the customer. They recognize that they make a difference. This recognition is part of the engine that drives their customer purpose.

Change is difficult, for people as well as companies. When it comes to initiating change, internal focus and complacency is common within organizations and among employees. In most cases, this complacency is deadly for the customer, who lives in a world where change frequently brings new solutions to problems.

Over the long term, complacency and fear of adjusting to the market can also be deadly for organizations. Recent business history is full of stories about overconfident or complacent companies that, modeling their future on their past success, failed completely while more viable competitors consumed their market share. Eastman Kodak comes to mind: Although Kodak invented the first digital camera, its insistence that film was its primary product resulted in the company’s eventual bankruptcy while the digital camera revolution took place under its nose, building on its own ingenuity. We suspect that what contributed to Kodak’s downfall was that either the culture had a dearth of hidden leaders, or senior leaders were so ensconced in their positions that hidden leaders could not make a difference.

We also know of examples where top-level management listens to hidden leaders within their organization. For example, Google is famous for implementing frontline employees’ ideas about products and projects that address unseen customer needs. Google Earth, Google Maps, and AdSense—which create significant revenue for the company—were all bottom-up projects that Google senior management was wise enough to embrace.

Listening to hidden leaders can be an important weapon against organizational complacency. Because they are customer purposed, hidden leaders look for ways to keep up with customer needs and market challenges. They are often the ones advocating improvements and responses to better meet customer needs. These champions of change will challenge the status quo, no matter their positions in the existing hierarchy. They are determined to serve the customer well, even if that means working against existing systems and assumptions.

This doesn’t mean that hidden leaders are rebels. They are people willing to question and press for continuous improvement and innovation because they believe in the importance of the value they provide to customers. It is worth noting that we do not identify hidden leaders as change participants, ready to comply with change. We see them as change champions. As such, they are an important driving force. They provide the impetus and create momentum for change because the customer is their primary stimulus for doing the work.

Hidden leaders become champions of change when that change is something that will benefit the customer. To understand any change initiatives, these leaders ask questions to understand how and why the change will positively affect the value the company provides to customers. Once they understand the importance of a change, they will ask questions to understand their colleagues’ fears and concerns about the change. These questions will also emerge as a hidden leader initiates change ideas within the work area. Once this understanding is established, the hidden leader uses communication skills to help others understand, accept, and embrace the importance of and reasons for change and change initiatives, whether mandated by management or initiated on the front lines of the organization.

Because they are customer purposed, hidden leaders understand what is in the customers’ best interests. (In our opinion, this ability has become increasingly rare for too many organizations.) Unafraid of promoting change, hidden leaders listen to customers carefully. They pay attention to the conditions that are driving customer needs. They realize that neither the customer nor the needs exist in a vacuum but are part of a bigger picture.

Hidden leaders understand the context of how customers use their products and services, and they pay attention to progress in areas seemingly unrelated to their company’s concerns. This allows the leaders to uncover unseen or complex issues that could undermine the organization. Armed with this information, they conduct in-depth conversations with colleagues about the organization’s approaches and how they impact the customer. They promote their insights into how the company can respond effectively.

Further, hidden leaders use their strong communication and persuasion skills to challenge the status quo collaboratively. They ask questions to understand the doubts or fears of those who oppose change. They gather information needed to justify a change and then address others’ doubts and fears by asking “What if?” questions to help doubters understand the potential benefits of a change. They realize the far greater power of helping someone draw her own conclusion versus preaching to her. They encourage people to adopt new practices that better fulfill customer needs.

We disagree with the premise that people don’t like the idea of change. Each of us can happily envision more desirable states involving change: lost weight, more money, or better circumstances of some kind. People often talk about the benefits incurred by progress, which inevitably requires some change.

It’s not change itself to which people object; it’s the path to get there that they don’t like so much. It is the diet, the hard work, the new routine to adjust to, or the unfamiliar or ambiguous tasks to be taken on. That’s what makes change difficult for people.

In business, employees often discuss what they would like to change in an organization or how things could be better. Gathered around the proverbial water cooler, they spend a lot of time discussing the changes they would like to see in an organization. What people in companies dislike is the process of change or, worse, a badly managed change initiative. A forced or thoughtless change process can make people rebel and undercut the change implementation.

Early in Scott’s career at a consulting firm, senior management presented a great vision to transform the company. It promised a fundamental shift in the business. Instead of offering development programs to sales organizations, the firm would provide a broad array of solutions that would address everything a sales organization needed, from sales process to customer relationship management systems and everything in between.

There was great excitement and enthusiasm about this change for the business. People felt it was necessary to stay ahead of the competition. Almost everyone was interested in the new ways they would be able to support clients. So when it came to liking the idea of the change and the vision of what could be, there was no problem.

In the next year, most of that positive energy and enthusiasm faded. What had followed the change-initiative announcement was an array of misfires. New products didn’t launch. Management set inconsistent objectives. The company reorganization left most employees wondering why things had changed at all. A series of initiatives, one after the other, each with conflicting objectives, made it hard to focus on serving clients and maintaining current business. Doubters emerged, some loudly. Employees worked in survival mode as the company downsized and lost market share.

Even within this chaos, not once were people upset about the idea of change to the new customer relationship management system. It was the process, the uncertainties, the conflicting initiatives, and the difficulties of making the change real that demoralized employees. Had these things been managed well, the change would have been effective and successful.

Through their skills as champions of change, hidden leaders can be management’s secret weapon to help others in the organization accept, commit to, and implement change initiatives. Engaging hidden leaders in change implementation helps clarify the change process for others because the leaders focus on what is best for the customer. Ultimately, they help individuals and groups accept transitions and new situations by translating big efforts and initiatives into practical, clear tactics.

For example, we were working in a large computer-networking company. The field engineering team faced a range of problems, all related to clients demanding new tasks as projects progressed. The team’s managers, responsible for controlling projects, often accepted these demands as part of the teams’ charter to satisfy each customer.

Frustrated by moving deadlines and growing budgets, one supervisor began to document the problems caused when the team accepted unforeseen client changes. She illustrated the impact of failing to manage these requests effectively. Most notably, the supervisor showed that clients were unhappy because initial deadlines were missed and communication about changes was poor. In addition, the engineering company was not meeting the financial profit margins necessary to run a healthy business.

Unlike the other supervisors and managers in field engineering, this hidden leader understood that clients were satisfied when they received clear communication and on-time projects. Few clients were trying to push for free labor; they simply saw additional needs and wanted them addressed as they emerged. For clients, money wasn’t the issue so much as ensuring that they had a work product that solved their problem, on time.

With this customer perspective in mind, the hidden leader worked with other managers to implement a simple change-order process. It improved communication between clients and the engineering team, ensured that deadlines were met, and created additional compensation when clients’ needs required additional work past the scope of the original project.

The hidden leader’s customer-purposed efforts made the company’s clients much happier. Now everyone understood clear expectations for the work performed, and people met deadlines with the right solutions. The organization increased its bottom line because it was no longer reducing profits by doing work not outlined in original project plans. By being customer purposed, this hidden leader created change in the best interests of customers and the company.

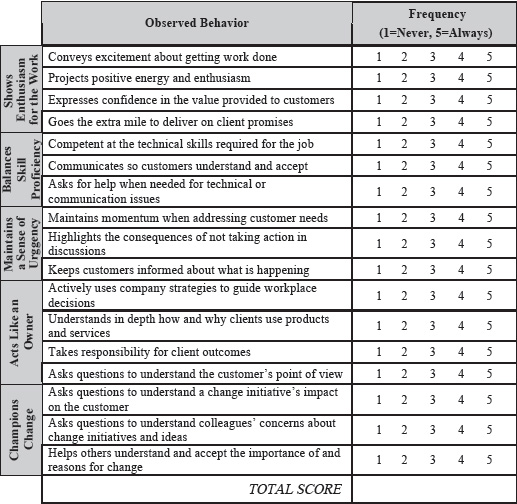

WORKSHEET: ASSESS THE CUSTOMER-PURPOSED HIDDEN LEADER

Think of a specific member of your team who you suspect is a customer-purposed hidden leader. Then read the descriptions below. For each one, circle the number from 1 to 5 that reflects how often you see that person behaving in that way. The higher the ending number, the more likely you have a customer-purposed hidden leader. The online worksheet will calculate for you automatically.

Hidden leaders bring being customer purposed to the table, but as a manager you can ensure that customer purpose expands throughout your organization. By enabling customer purpose in employees, you support the natural tendency of hidden leaders and help others develop customer-purposed skills.

We see the process of developing customer purpose in a company as encompassing two critical steps: refining the definition of “customer” for all employees and cascading the value promise throughout the organization.

Refine the Definition of “Customer”

As Peter Drucker eloquently said, “The purpose of business is to create and keep a customer.”3 A customer (or client, depending on your industry vernacular) is someone who pays your organization for a product or service. Plain and simple, revenue from customers pays the bills for a business. Without them your company does not exist.

In the last several decades, we have found that the concept of the “internal” customer increases confusion about who the real customer is. The concept of internal customers became popular because people were treating each other poorly within organizations. Employees felt unable to work outside of their departmental silos or needed to work more effectively and collaborate on projects. “Internal customer” became code for “treat me with the same kind of respect and provide me with the same kind of responsiveness and focus as you would our paying customers.”

In our experience, the notion of the “internal customer” has had a positive impact in some cases. But it has also diluted the importance of the paying customers of an organization. When internal customers drive an organization’s processes and goals, there is too much time, effort, and energy (not to mention money) spent doing things to please people within the organization. While this approach has improved how some people are treated within an organization, it is a salutary and peripheral impact at best. In most cases, these efforts have no value for the customer who pays.

The intent of using “internal customers” to engage everyone in treating each other with respect is fine. Pragmatically, everyone becomes a customer of someone else in the organization.

In contrast, being customer purposed is a more dynamic and powerful attitude. Being customer purposed brings a laser-like focus on the customer who pays. It unites everyone in the organization toward reaching a common goal. It helps align priorities and sustain focus, regardless of where in the business any individual works.

Because of their integrity and relational leadership skills, hidden leaders naturally treat colleagues respectfully while pleasing paying customers. Their tendency to act like owners also means they recognize the contribution of all colleagues to fulfilling the value promise. These attributes make the concept of “internal customer” irrelevant to hidden leaders, while their being customer purposed drives them to express value to customers who pay the bills.

Cascade Your Value Promise

Cascading an organization’s value promise means communicating a consistent message from the C-level, delivered in a multitude of ways, about the value the organization provides to the paying customer. This message also makes it clear how each person’s responsibilities contribute to that value.

Cascading creates a clear line of sight between an individual’s daily work activities and the long-term success of the company. This isn’t a business strategy per se. It is a process for implementing your corporate strategy and ensuring that everyone in the organization aligns his goals and actions with the strategic goals set by management.

One hidden leader we saw at work clearly understood the value promise of his organization. He was a crew leader in a car shop of a major railroad. The job of railroad car shops is to take any of the railroad’s damaged freight cars—from three-decker auto cars to coal bins to traditional boxcars—and make them work efficiently. Anything could be wrong with a car sent to the shop, from the sets of wheels on which the cars rested to sticking boxcar door slides to failing brake hydraulic systems. Each issue had its own coded defect that had to be addressed. The men and women in the shop saw it as their job to get each car out of the shop as quickly as possible without shortcutting welding quality, safety, or function.

But there were no coded defects for cars that were just ugly.

You’ve seen the ugly cars: tagged by gang members, dented from cranes loading truck boxes onto flatbeds, or painted in various shades of primer grey and green.

Car shop crews are proud of their skills. They like to show them off. They could have made every car look like it just rolled off a display floor for train cars.

The car shop crew leader was among the most skilled of the workers. He had been at the shop for decades, though he was only in his forties. He, too, wanted to push out cars that looked like they were brand spankin’ new.

But besides his functional skills, the crew lead also had one of a hidden leader’s vital skills: being customer purposed. He knew how his crews’ work delivered the value promise of the railroad. The railroad’s job wasn’t to look pretty, but to deliver freight for customers. The longer any one car spent in the shop being gussied up, the less time it could spend making a living for the railroad moving customers’ freight.

So the crew lead tirelessly taught a saying to his crews: “Ain’t no defect for ugly.” Which meant: Short of a safety or performance issue, ugly cars would roll out with the same ugly that they came in with.

It drove his crew nuts. They almost liked it when a tagged car came in with a functional defect that would require painting the whole thing, so they could make it pretty. But without a coded defect, they had to let them roll.

The crew lead was customer purposed. “Ugly” moves freight just as well as “pretty.” And the value promise of the car shop was ultimately that of the railroad: to move its customers’ freight efficiently. The railroad had ensured that the company’s value promise cascaded throughout the organization, even to the floor of the car shops.

In our experience, this cascading process is something most organizations try to do but few do well. Typically, we see a value promise resonating in the executive boardroom with upper-level management. The promise gets progressively diluted the further from the executive suite it goes in the organization. This dilution stems from executives thinking that explaining the value promise once, or through one method (all too often email), means all employees will see the connections between their work and the organization’s goals. It also stems from supervisors and lower-level managers not regularly helping people on the front lines link their job duties to the value promise for the paying customer.

Cascading the meaning of the value promise effectively (or, by extension, strategic goals) requires a comprehensive approach:

![]() Develop communications in as many media and contexts as possible. Common channels include newsletters, executive-message videos, and posters. In addition, team meetings, individual development conversations, problem-solving sessions, and one-on-one coaching provide excellent cascading opportunities. The resulting process improvements, stakeholder and customer meetings, and responses to the market, in alignment with an organization’s strategy, can make a tremendous difference for an organization.

Develop communications in as many media and contexts as possible. Common channels include newsletters, executive-message videos, and posters. In addition, team meetings, individual development conversations, problem-solving sessions, and one-on-one coaching provide excellent cascading opportunities. The resulting process improvements, stakeholder and customer meetings, and responses to the market, in alignment with an organization’s strategy, can make a tremendous difference for an organization.

![]() Time communications to support each other. For example, support an executive video message with posters, innovation competitions, and team meetings centered on the message and related strategies. Follow-up messages from managers and executives reinforce the message’s importance. Take care to not overwhelm people with continual messages or ones that contradict each other.

Time communications to support each other. For example, support an executive video message with posters, innovation competitions, and team meetings centered on the message and related strategies. Follow-up messages from managers and executives reinforce the message’s importance. Take care to not overwhelm people with continual messages or ones that contradict each other.

![]() Ensure that the value conversation happens for employees at all levels. Supervisors and managers can maintain open dialogues about how employee actions help paying customers. These conversations can be in the context of development discussions, problem solving, decision making, and reporting procedures. This type of conversation is common in sales organizations, where the answers are often obvious. Other functional areas can benefit from taking this customer-purposed approach and defining their value in the overall picture of the paying customer.

Ensure that the value conversation happens for employees at all levels. Supervisors and managers can maintain open dialogues about how employee actions help paying customers. These conversations can be in the context of development discussions, problem solving, decision making, and reporting procedures. This type of conversation is common in sales organizations, where the answers are often obvious. Other functional areas can benefit from taking this customer-purposed approach and defining their value in the overall picture of the paying customer.