CHAPTER 6

The Engineer

Aabha always had two plans. She had the plan for what she wanted to do—and the plan for what she thought she should do. She loved visual arts, but she also loved logical reasoning. A dreamer with a fondness for pragmatism, she was pulled in two different directions.

Her parents had always encouraged her to follow her passions, no matter how fanciful they seemed to her, so she studied Art History at a top Canadian university. After graduation, she found herself immediately underemployed. Her instinct for safer planning kicked in. Reluctantly, with only one year in the real world behind her, she continued on to law school, where she graduated with distinction.

At school, Aabha met her future husband Rajeev, who was finishing his medical degree. Despite her lack of enthusiasm for the profession she was spending three years preparing to enter, Aabha found that her talents made her an excellent lawyer. Underwhelmed by the prospect of a life in law, Aabha halfheartedly accepted a job at a top white-shoe firm in New York while Rajeev did his residency in cardiology at a nearby medical center. They were the poster couple on the rise.

Aabha found life at the law firm paralyzing. She worked constantly for bosses who mistreated her. The ruthless partners never gave her sufficient time to properly prep her cases and frequently berated her, expecting her to sacrifice her personal life for the benefit of the practice just like they had. With Rajeev perpetually on call at the hospital, the couple had very little time together. On the rare occasions her colleagues had the time to get together after work for a beer, they’d complain about their mean-spirited taskmasters but seemed to find the sweatshop experience strangely exhilarating.

Aabha finally found a like-minded ally when she was assigned to a project with a seasoned attorney named Chetana. Also Indian, Chetana admitted that working under the blue-blood boys could be oppressive but noted that things had improved considerably over the years. They met to discuss the case every other day over afternoon tea. When Aabha confessed that she was seriously considering leaving the firm, Chetana observed how similar the two were and encouraged her to find ways of incorporating her personal interests into her work and stay on until she reached partner.

Reenergized by the friendship, Aabha worked diligently to win the case, which dragged on over a year before it was successfully settled. One afternoon, Aabha stopped by Chetana’s office to share an idea to add an art litigation practice to the firm that would enhance their ability to gain both institutional and estate deals. Aabha saw it as an opportunity for the firm to grow a new line of business and a way for her to bring her personal passion for art to the office. Chetana smiled and said, “I’m sorry, but I can’t take this to the partners. We both know that they will never go for it. It just isn’t a priority for the firm.” Silent and broken, Aabha left the office. Three days later, she quit. Chetana called and left a warm invitation to talk, but Aabha never returned the call.

After weeks of second-guessing herself, Aabha went to work with a friend who owned a trendy art gallery in Soho. She enjoyed her work but found that things moved a bit slower than she preferred. Months passed, and she had all but forgotten her legal career when she received a phone call from Chetana asking if she’d be interested in taking a case as an adjunct member of her team. The firm was representing a Latin American museum that was suing a deposed dictator to recover some jewelry and other treasures of historical significance. After considerable reflection and subsequent hesitation, Aabha took the case. Surprisingly, she found the work engaging and was shocked by how much she now liked collaborating with her old colleagues from the law firm.

The project inspired her to start a boutique legal practice that specialized in matters of art. Aabha loved the independence that came from her sole proprietorship and the interdependence that the affiliation with the company brought. She had found her own voice, her real expertise, her bliss. The two plans she’d had from the beginning and the two passions she’d long convinced herself were simply incompatible had come together in an unexpectedly satisfying way.

The Luminous Pragmatism of

Engineers

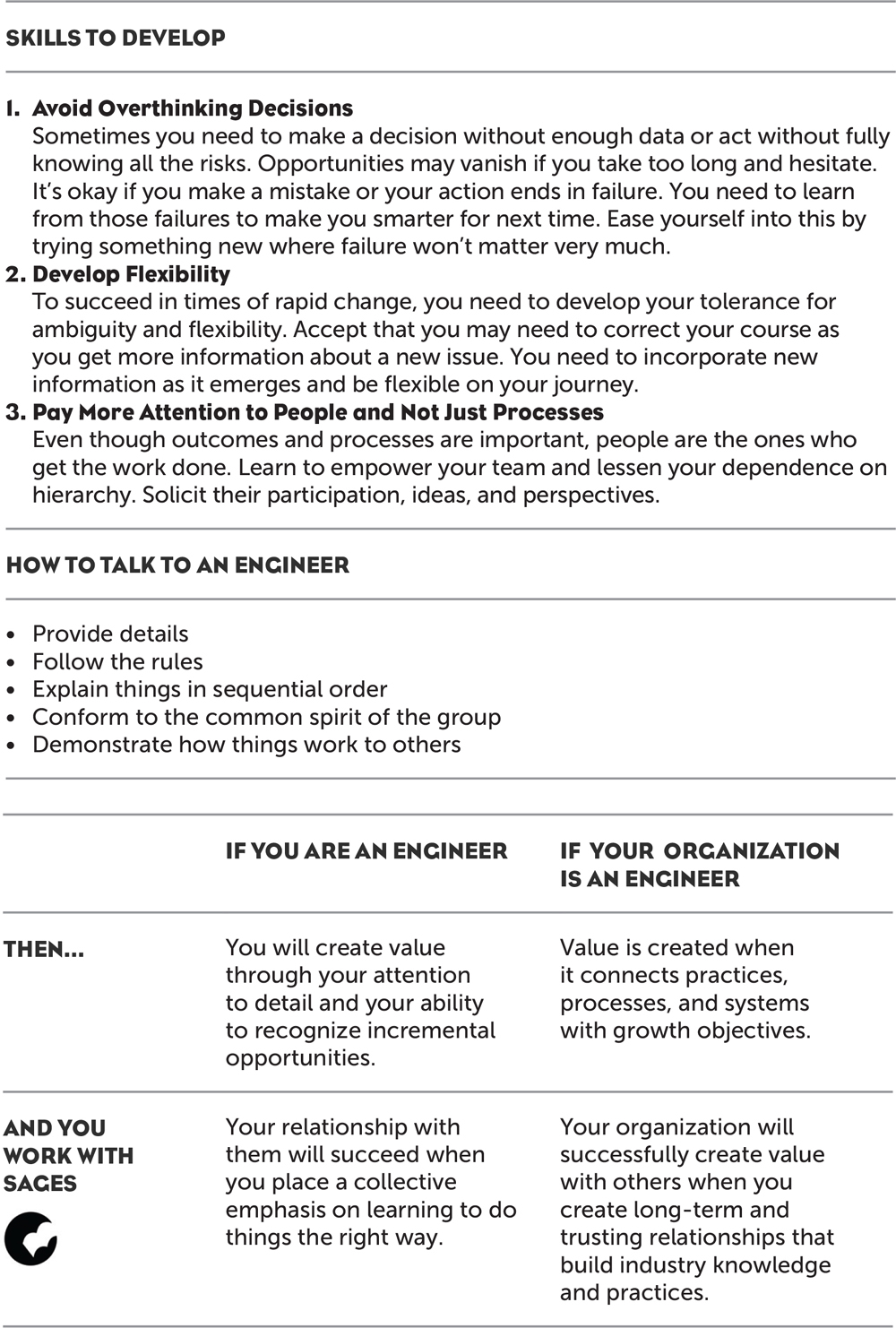

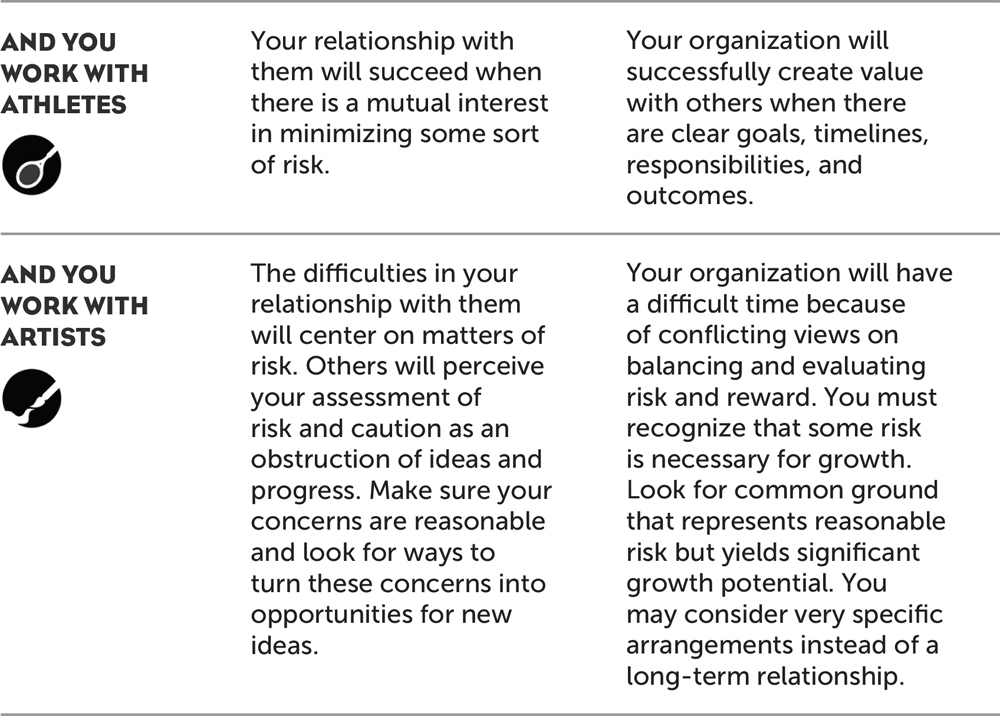

She may not want to admit it, but Aabha is an Engineer through and through. All of the qualities that make her a stellar lawyer—her luminous pragmatism, her methodical approach to problem solving, her penchant for objectivity, and her astonishing persistence—are the characteristics that define anyone with this dominant worldview. That she is a reluctant Engineer makes her all the more perfect as a model. For Engineers are much more complicated than the number-crunching, by-the-book people we might expect them to be. They are thoughtful, sensitive thinkers—as creative as Artists—yet they thrive in environments with procedures and established ways of doing things.

Engineers are systematic, disciplined team members. They embrace reliability as they work to eliminate deviance. They love to take preexisting ideas and products and make them into something bigger—something reproducible, global, universal. What they seek is efficiency. They strive for incremental innovations. They want quality—foolproof systems that can make a lot out of something already proven to be great.

At the organizational level, the Engineer organization is a large-scale company with many rules and structured, hierarchical ways of doing things. Since the organization’s growth is driven by process, it is easily scalable. Think Dell Computer. Think McDonald’s. Think Boeing and Toyota. Think British Petroleum. For these companies, failure is not an option. They are companies that make their money on scale. In these companies, you will always find complexity—there are many parts to manage. This is a slow-moving, low-risk kind of growth. It certainly won’t change the game, but it is most definitely a growth you can count on.

Taken too far, Engineers become control freaks. It’s the sweatshop sensibility that Aabha hated most about her law firm: the unthinking celebration of productivity at all costs. That Aabha could see the dark side of this in her colleagues makes her an especially self-aware Engineer. Indeed, her impulse to bring some creativity into the firm was a great one—for the people that Engineers need most in their lives are the ones most of them have the least in common with: Artists.

Artists and Engineers have a lot to teach each other. While Artists shake up the rules of Engineers, Engineers minimize the chaos of Artists.

What Engineers show everyone is that an innovation doesn’t have to be radical in order to be meaningful or worthwhile. It’s often better to think smaller and look at what’s already out there. Instead of trying to find something no one has seen before, Engineers create extensions of current solutions. They take something that already exists and make it a little different or better. They apply more effective uses of low-cost, low-level systems and technologies to transform an old service into a more efficient one. The key idea is not newer but better, cheaper, and faster.

The Understated Genius of an

Engineer’s Innovation

We often discount or dismiss the kind of innovation that Engineers call for because it doesn’t sound exciting enough. Cool, shiny, and sleek: these are the qualities we associate with top-shelf innovations. That’s because we’re constantly confronted with magazines and Internet lists of the most innovative companies that are essentially just beauty contests. At the top of all these shimmering lists are blustery bands, glitzy gadgets, and chic designers.

But take a closer look and you’ll see that these sparkly objects aren’t really the best innovations. The most valuable innovations don’t have extraordinary stories and they’re not cool, shiny, or sleek. They’re plain and understated, they blend in with their surroundings—they’re the inventions that don’t catch our eye. They’re hidden in plain sight.

That’s the great insight that Engineers have to offer the world: true innovation happens behind the scenes. Sure, new technologies, products, and services that we perceive as breakthrough advancements look exciting, but the meaningful innovation is in the larger, more complicated processes that make those things possible.

There’s no new miracle drug without discoveries in chemistry, manufacturing, and control processes. There’s no new animated feature film without a revolution in software-coding practices. There’s no new electric car without developments in material sciences.

The Engineers are the people who make this kind of growth and development happen. They’re the underrated back-office superstars—quiet, diligent individuals working out of public view, often in bureaucratic departments. These are the people who can see where the dots connect, who can tell where there are opportunities for change.

Think of the structure of any large organization in terms of a mid-office and a back-office staff. Mid-office members have leadership positions like Chief of Staff and Operating Officer. The back-office members work in Legal, Financial, Information Technology, and Human Resources departments. All of the units in any office are vertically oriented so that everyone reports to their own sector’s manager. The few places in an organization that are also horizontally oriented are these back-office departments. Here, people can look across the business: thanks to their back-office viewpoint, Engineers see where the points of contact are between all the parts of the larger company.

Example:

The Back-Office Triumph of a Wall Street Bank

It is this back-office kind of thinking that helped spark a wildly successful innovation in a large, well-respected Wall Street investment bank at a key moment of transition.

When the director of executive training first noticed his company was in a crisis, it was the end of the go-go ’90s, when all of the mega-mergers were ending, and all of the powerful investment firms were looking for new ways to make money. This venerable old banking institution was out of position: while other banks were experimenting with different strategies or trying to put together mergers, this bank had stayed traditional, maintaining the same structure it had relied on for nearly one hundred years.

As a result of this dependence on the old way of doing things, the company was disjointed. Each of its locations around the world was successful, but there was very little—if any—communication between each of those locations. Now, the executives wanted its regional chief financial officers to be more active in advising the leaders at the center of the company, to be more anticipatory and responsive in planning for the future.

Soon, with the help of some Engineers’ perspectives and the push and pull of constructive conflict, the director recognized that there was an opportunity for a new source of revenue—a previously untapped area of income: the strategies developed by the legal team and other behind-the-scenes sectors. These back-office teams of Engineers had come up with effective solutions to the company’s problems, to issues that many other big global companies face. In particular, they had mastered the process of moving their branches from one location to another, relocating from one area to a new one without creating a lot of exposure. They had discovered the legal tax maneuverings and the offshoring techniques necessary to mitigating risk.

The company went on to take these winning ideas and strategies developed by back-office members and repackaged them so they could sell them as a service to other industries.

The issue was that the main controllers and financial officers of the organization were simply not aware of how their company worked, what went on behind the scenes. Once they learned what they could do with these invaluable sources of creativity, they made use of these back-office strategies. The back office started creating a book of business policies and sold it worldwide. This new initiative brought in a huge amount of revenue for the banking firm. While some businesses that bought these strategies didn’t replicate the original success, many—especially those in similar cultural environments—did recreate that success.

The point is this: everyone always talks to the new technology people and the trend experts—the Artists—when they want to achieve radical innovation, but the people you should talk to first are the ones in your own back office—the Engineers. These are the people who really know where and how the business comes together. They see the opportunities for growth before anyone else does. They are the ones who can search for and reapply great ideas quickly. Don’t look far for new talent. Your brightest stars are likely already in your backyard.

Exercise:

Rapid Prototyping

You don’t have to be technically proficient or intensely disciplined to think or see the world like an Engineer. In the Engineer’s spirit of rulemaking and rule following, there are easy ways to reproduce the skillset of these methodical innovators. If you can’t find or recruit an Engineer—or just need that reliable kind of incremental growth for yourself—here is an exercise for tapping into your own inner Engineer.

When launching any new project, it’s best to start with a prototype because you want to prove the concept works before you spend a lot of time and resources. What you want to do is to develop the idea as quickly as possible so as to minimize expenses and risk. Then, learn what really works and what really doesn’t, both in the making and selling of the idea. And finally, make adjustments to advance to full-scale production.

Prototyping any idea, both products and services, as well as any solution that enhances our own lives, is a highly iterative process: version one, version two, and so on. It is unlikely that you will get it right on the first try. One of the biggest mistakes people make when launching a new project is to get stuck in the planning cycle where we spend too much time strategizing and not enough time testing our ideas in the real world. Use the followings steps to develop your prototype:

1. Create criteria for success. What is required is that we engage in the constructive conflict of the four dominant worldviews to develop a shared and clear definition of the results we seek from our prototype including specific target number, benchmark, and resources:

• Artist: a unique, never-before-seen, one-of-a-kind prototype

• Engineer: a predictable, works-everywhere, turnkey solution prototype

• Athlete: a valuable, defeats-your-competitors, first-to-market prototype

• Sage: a principled, mission-affirming, community-sustainable prototype

2. Prioritize the features you need. Make a list of the most essential features from the point of view of your target market. For example, if our idea is to commercialize our grandmother’s recipe for Italian spaghetti sauce, it makes sense to focus your efforts on testing the sauce in restaurants first before you move on to concerns of marketing, manufacturing, and distribution. If you don’t get the first step right, there will be no second step. Ask yourself the following questions for each feature you are considering:

• How important is this feature to the success of the prototype?

• How many potential customers will find this feature essential?

• Will this feature determine the success or failure of this prototype?

• Are there substitutes for this feature that are cheaper, faster, or better?

• How much value does this feature bring to the prototype?

3. Develop a Minimal Viable Product (MVP). Working with the list of features, get your prototype into production quickly and inexpensively. Trade-offs are inevitable at this stage, and you must consider the best available option to get your prototype into production. New information and technology have made prototyping easier, faster, and less expensive than ever. Prototypes can be made in a number of ways from the very inexpensive to the very expensive, from simple pencil sketches to 3-D printing. The objective is to spend as little time and money as possible because the real aim of this phase is to accelerate learning so that adjustments can be made in future versions.

4. Find what worked and what didn’t. Use the constructive conflict from the four worldviews to make innovative adjustments to the prototype. In addition, establish some simple rules of thumb, based on the real information gleaned from the prototype, to be implemented going forward. This way, you learn from your mistakes instead of repeating them in the next version.

5. Develop your next version. It may take several attempts and versions before you have a scalable prototype.

6. Finally, once you have a viable prototype, you need to find the most efficient and effective way to operationalize it to scale. How this is done is primarily dependent upon the goal of the prototype. For example, if the aim of the prototype was to create a blog on the Internet, getting the site up and some initial network marketing in place may be all that is needed. On the other hand, if your grandmother’s spaghetti sauce turns out to be a winner in the prototype phase, you may need to start marketing efforts with food companies and restaurants, or alternatively negotiations with banks, financiers, manufacturers, and distributors.

Prototyping is a great way to minimize risk while learning what works and what doesn’t. The key is to spend as few resources as possible in the shortest time possible. It’s a way to accelerate failure, not to avoid it. If your first prototype doesn’t work, that’s fine. The information you get from making it and running that experiment will help you in the future. The sooner you get results, the better off you are. Remember to develop and evaluate your prototypes from the four dominant worldviews. And like climbing stairs, take it one step at a time.

The Artistry in

Engineers

While the Engineer is almost the precise opposite of the Artist, there is an art to the precision and commitment to procedure that the Engineer brings to any project, an art just as brilliant and powerful as the Artist’s wild fantasy of the future. Behind all of the rules, efficiency, and methodical reliability is an imaginative vision. The rules and the vision can and do coexist if the Engineer plays it right. The triumph is seeing the compatibility of the two things Aabha always thought were completely at odds with each other: the plan of our dreams and the plan of our needs.

Summary

Reliable and logical, Engineers like to make things work very efficiently. They rely on processes and procedures to produce the highest quality products and services every time, everywhere. They can grow by reducing their tendency to pore over data and pushing themselves to seize an opportunity when it presents itself. The challenge is for Engineers to embrace their inner Artist and learn to be more comfortable with ambiguity and the unknown.