CHAPTER 10

PURPOSEFUL CONVERSATIONS

“As far as we can discern, the sole purpose of human existence is to kindle a light in the darkness of mere being.” —Carl Jung

“A mighty flame followeth a tiny spark.”—Dante

The human desire to identify and spark a purposeful light in our days is a very real part of our orientation to work—where after all, we spend most of our waking hours. When we have a clear purpose to this time, and our path is illuminated, work is invigorating. We have harmonious passion, or at the least, contentment. When we feel as though we’re running in circles, or spiraling downward, work is somewhere between boring and soul crushing. We’re counting the hours (or, if nearing retirement, years) until we’re free.

Helping clients to get clear about their purpose is a core part of many coaching engagements. Even if that’s not the presenting issue, it almost always comes up as it’s linked to everything else. If passion is the accelerator, it’s purpose that steers the car. Purpose is our driver. It’s the reason we want to get better in the first place. Purpose feeds intrinsic motivation. It’s what creates meaning from our labor.

Finding an inspired purpose is a question for young professionals as well as seasoned CEOs, for people working in nonprofits and on Wall Street. It’s an equal opportunity desire. We all want purpose, even if we don’t know where to find it. When we don’t have a clear purpose, we feel something is missing. It’s hard to capture, and slippery when seized.

Finding an inspired purpose is an equal opportunity desire in every type of job, at every point in our careers.

Consider the case of Brian, who represents a common situation of many mid-career professionals. Brian worked diligently in his career to become partner at his law firm. He put in the sleepless nights, forsaking many evenings at home with his family, and hustled to service clients and bring in new business. He’d never liked the culture of high-pressure billing at law firms, but he played the game and played it well.

Finally, he was in the process to make partner, and all signs were that he was a shoo-in. He wanted to be happy about it, but to his surprise, he was ambivalent. Becoming an equity partner required a substantial financial commitment that made Brian feel trapped. Few partners leave once they make it in. He began to question why he became an attorney in the first place, and where he wanted his path to go from here. He made a gutsy decision and deferred the partner process for a year to fully explore his options. In the end, he left the firm to become in-house counsel for a company whose values aligned with his own, and which allowed him to be part of building an organization.

Another very different example is Nancy, who started her own company filled with purpose to create the kind of business she’d always dreamed about. She hired great people, built an energizing culture, and worked with forward-thinking clients. Nancy ran the company with a “no jerks” policy for employees, partners, and customers. Everyone in the company’s orbit was respected and respectful. Nancy had never felt so on her game.

Five years in, Nancy took in venture capital to help finance an expansion. The VCs had their own ideas for how Nancy should grow the company, as well as a timeline for an exit. They brought in a hotshot COO to guide the company’s growth. Within a year, Nancy’s company was making more money than ever, with a new management team as well as additional investors. Nancy, however, was miserable. She barely recognized the company she’d started, and dreaded going into work. She’d lost her entrepreneurial spirit to bring her vision into the world, and felt lost without it.

Nancy tried a few different avenues to get her motivation back, including running a strategic division that specialized in new product development. However, she kept bumping up against a creatively stifling culture that didn’t feel like home. Eventually, she worked out an exit agreement and left.

As these two examples highlight, purpose is a personal endeavor. It exists within us, and it may be impacted by the situations in which we find ourselves. We can have it, lose it, and regain it. We may only have a partially formed seed of purpose that either flowers or gets buried, depending on the environment.

We hear a lot about purpose-driven organizations like Starbucks (“to inspire and nurture the human spirit—one person, one cup, and one neighborhood at a time”) or Nike (“to bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world”).1 And yes, it can be inspiring to work for an organization with such a clear sense of purpose—especially when that purpose aligns with your own. On the other hand, if there’s an explicit or implied corporate purpose that conflicts with your values, it can make you miserable.

But for most people, the process of finding purpose exists on a more nuanced, personal scale. It’s less about a grand vision outside of ourselves and more about the vision we possess internally. Those who inspire us know this. That’s why they’re willing to have conversations about purpose, even pointing to it when we’re not looking for it. Helping someone find that internal spark of purpose, or reignite it, is a transformational act. Inspire Path conversations around purpose may occur in front of a room full of people, helping them to see a higher calling for their work. Or they can be one-on-one, helping another person to kindle that light to want to be, and do, more.

A purpose that ignites us is personal. It’s less about a vision outside of us, and more about the vision we possess inside.

PURPOSE: BIG, SMALL, AND IN THE MIDDLE

We can engage in Inspire Path conversations about purpose pretty much anytime. We’re so often in these conversations inside our own minds, that when someone else goes there with us, it’s appreciated. You may be thinking that it’s awkward to go up to your colleague on any given afternoon and start talking about his purpose. Like most Inspire Path conversations, timing matters. You have to have the space to be present, personal, and passionate about the topic. But I would also say that there are many levels to purpose, and each has meaning. You don’t have to go nearly as deep as you think.

Purpose can seem grandiose, mostly because we think of it in big terms. This is your life’s purpose, the Big P, the grand design for your life, your organizing principles. Many people never figure this one out, but certainly any step closer is positive. It can be hugely motivating to have someone help us in this search, but it’s intimidating to enter into this conversation. We often leave the Big P to the professionals—psychologists, coaches, or spiritual leaders. Our family, close friends, and mentors help, too.

On the flip side is the small p purpose—the purpose for what we’re doing at the time. This is why the project you’re working on feels significant, or why it’s important that your research fits into the larger program. Small p purpose brings context and a “why” to our efforts. Even helping to illuminate this basic level of purpose brings empowerment. This is why good team leaders strive to connect daily tasks to a larger company mission. It contextualizes the work, making it about something larger than one person.

In between these types of purpose, there’s the middle—which we can aptly call middle p purpose. This is the place where inspired leaders can really have an impact. This middle p purpose is contextual. It’s about finding work that’s meaningful to us for where we are at this moment in our lives and in our careers. It helps to transcend what we’re doing in the here and now—to find the patterns that enable us to go further in our journey, to find enhanced enjoyment, to tap into our passion, and to be in service to a larger cause. It’s our own personal why: why, given all the choices before us, we are doing what we’re doing at this point in time, and why it’s important to us.

Leaders can have a great impact in helping another find work that’s meaningful for where one is at this moment in one’s life and career.

The middle p place offers a practical conversational platform about purpose. I’ve witnessed people in this area of discussion get a firm handle on a larger why for their efforts, and visibly consolidate their energy behind it. Here are a few examples:

![]() A leader in a chaotic culture determines she’s in the biggest learning situation of her career.

A leader in a chaotic culture determines she’s in the biggest learning situation of her career.

![]() A manager in a stagnant job realizes his main purpose is maximizing family time with his kids through their teen years.

A manager in a stagnant job realizes his main purpose is maximizing family time with his kids through their teen years.

![]() A new professional decides she’ll use her unfulfilling entry-level job to better figure out her true interests and talents.

A new professional decides she’ll use her unfulfilling entry-level job to better figure out her true interests and talents.

![]() A CEO uses the power of his position to tackle a larger social cause.

A CEO uses the power of his position to tackle a larger social cause.

![]() An executive with a controlling boss learns to rise above the negativity to build higher-level relationships to further her career.

An executive with a controlling boss learns to rise above the negativity to build higher-level relationships to further her career.

In my research, I heard over and over again how particular inspirational conversations had helped to trigger this kind of personal definition. It doesn’t have to be a grand life epiphany—but if it is, that’s great too. More commonly, it’s a personal sense of purpose that enables us to find meaning for where we are, and to feel the pull of momentum carrying us forward.

Simon Sinek, author of Start with Why, helps organizations and individuals find purpose.2 One of his book’s themes is that if we don’t know why we’re doing what we’re doing, we won’t know how to accomplish our goals. But if we can determine the why, our perspective for how expands dramatically. Further, we find purpose not by starting with the goal and working backward (I want to get promoted because I like a challenge) but by starting with you and letting that lead to a goal (I like challenges, so how can that manifest?). All too often, we talk ourselves into a goal without ever having thought through why we want it, as was the case of Brian, in our earlier example, who struggled with wanting to be partner at his law firm.

THE PURPOSE OF PURPOSE

As we’ve discussed, being inspirational is about creating a space for others to come toward you. It’s subtle. It’s about establishing conditions for inspiration rather than forcing a preordained plan. After all, we can’t make someone be inspired—they have to choose that for themselves.

In the Introduction, I mentioned research by Thrash and Elliot that found three characteristics of an inspirational state: transcendence (an awareness of new or better possibilities), evocation (receptiveness to an influence outside of oneself), and approach motivation (feeling compelled to bring the idea into action).3 Further, Thrash and Elliot differentiated that we can be inspired by something as well as to something.

Purpose and inspiration are closely related in the research, and causally related in our own lives.

Having a purpose is inspiring to us, as are those who help us find it. When we are able and willing to be in a purpose conversation, to ask insightful questions, make recommendations, and role model possibilities, we are supporting all three characteristics of inspiration. We act as a trigger for inspiration in others. We’re the by in someone else’s inspiration—and purpose is the to.

Being an inspirational force for another may be enough of a reward. We get a big psychic boost from being that helpful. However, there are ample business reasons to support the development of purpose in others. Purpose and inspiration have been shown to increase well-being and goal progression as well as vitality, positivity, and life satisfaction.4 A study conducted by the firm Imperative and New York University found that purpose-oriented people are more likely to be leaders and to experience work as an opportunity to make an impact. The same study concluded that only 28 percent of the population is purpose-oriented, while 72 percent define work around external factors such as financial gain or status.5 With that yawning gap, the study’s authors argue that there’s significant room and benefit to bringing a purpose orientation into the workforce.

Purpose also has a relationship to self-motivation. In their seminal and oft-cited research, psychology scholars Edward Deci and Richard Ryan studied what creates intrinsic motivation.6 They developed a construct called Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which has been expanded upon by researchers around the world. SDT states that we have three innate needs that, if satisfied, optimize our functioning and growth: competence, autonomy, and relatedness. In other words, we have an inner drive to feel competent and effective, to control the course of our lives, and to have satisfying relationships with others. (Those who’ve read Dan Pink’s bestseller Drive will find these similar to Pink’s thesis that we’re driven by mastery, autonomy, and purpose.) We all have these drives, but they can be supported or stymied by our environments, as well as by our own mindsets.

When we help people tap into their purpose, we are not just inspiring, we are helping them to self-motivate. Purpose-driven conversations tie directly into these drives. We help people to figure out their strengths (competence), how to put them to better use (autonomy), and how to be part of a larger effort (relatedness). Sometimes people need to find all three, or to be reminded of just one, like competence. This is why the simple act of sincere, specific, positive feedback can be inspiring. We’re reminding someone of their competency.

When we help people tap into their purpose, we are not just inspiring, we are aiding their intrinsic motivation.

Finally, it’s worth noting that being a purpose-driven communicator is less of an event than an orientation. There’s no right time or place to have these conversations, which tap into that internal drive toward purpose as an important part of what it means to be a leader, a worker, and a human. What matters most is that both parties are open to having them.

A CASE IN PURPOSE: GOVERNMENT LEADERS

Though I work primarily with corporate clients, by living and working in the D.C. area, my work occasionally takes me into the world of government. Usually, I’m brought in to deliver a keynote to a federal agency. We all hear the stories of what it’s like to work in the government—byzantine rules, tenure-track career paths, and rotating political appointees in leadership. And yet, some of the most dedicated and smartest people I’ve known have worked in government. In my preparation to learn about the audience, I always ask about the organizational culture, to learn what this specific agency is experiencing, and what it is trying to instill.

Agency culture can vary tremendously. There’s a big difference between working at NASA and the Department of Education, for example. Every year, a federal employee job satisfaction survey goes out to all government employees where they rate their agencies on employee engagement and satisfaction. Since its founding in 2003 as a response to 9/11, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) continually ranks at the bottom of the list of agencies. It’s become such a trend in Washington that hearings have been called to discuss why morale at DHS is chronically low.7

Knowing some people who’ve worked at DHS over the years, I’ve asked about this phenomenon. There have been leadership changes and considerable integration issues from bringing twenty-two separate agencies together to form DHS, and that surely plays a role. But what I hear about most is the thwarting of purpose. There’s a disconnect between what the workers at DHS need to do, and what they can do—made even worse by negative public perceptions.8 Think about it: The mission of DHS is to keep the homeland safe. That means the TSA at airports, the Coast Guard, Border Protection, Immigration, Secret Service, and FEMA, to name a few. DHS covers everything from complex cybersecurity to stopping a runner at our borders. People often go to DHS from the military or are civilians inspired by the cause. Once they get there, they face an ever more sophisticated and mounting set of threats, and a general public that’s vocally frustrated. As I write this, U.S. airlines are encouraging travelers to post pictures of long security lines on social media to ease the backups at airports with the hashtag #IHateTheWait. As you can imagine, the comments are not kind.

Employees at DHS have stressful jobs, with incredibly high stakes—and are continually stymied in their ability to feel competent and to have a sense of control over their work. In fact, it’s the opposite: They are in the news regularly for their shortcomings while their budgets get cut, thereby limiting their options. Is it any wonder that so many DHS employees struggle to stay inspired and engaged? Wouldn’t you?

It’s not just DHS that faces engagement issues in the government. The oft-reviled stereotype of the government worker is a lazy, mediocre employee who is phoning it in until collecting an early and overly generous taxpayer-funded retirement. Again, not the people I’ve known. (And yes, there are a mix of good and bad employees everywhere.) Washington is a company town. Everyone here knows federal employees. They are Ph.D.s and researchers, economists and genomic scientists, CIA agents, congressional aides, and IRS investigators. They are budget officers, multilingual Foreign Service workers, and busy secretaries like my sister. To solve our hardest national problems, the government needs our best thinking, creativity, and inspiration. With this backdrop, you can see how important instilling a sense of purpose is for government leaders. Many government workers can make more money in the private sector. Some leave for that reason. However, most don’t. Known as career employees in Washington-speak, they’ve been in the trenches through multiple administrations trying to get important work done in some pretty tough circumstances. Feeling, and acting on, a strong sense of purpose is critical.

Brookings Executive Education, part of the influential Brookings Institution think tank, has been developing government leaders since 1957. It was the first organization to offer leadership training to the federal workforce, and is consistently ranked the highest in the industry. Thousands of government leaders have attended development programs through Brookings over the years. I presented at one of its leadership sessions, and was impressed by the creativity and energy of the government leaders in the room. Rather than being saddled with the difficulties of government service, they were enthusiastically exploring its possibilities. When I spoke to the Executive Director of Brookings Executive Education, Mary Ellen Joyce, I learned why. Joyce described a program built on helping government leaders find and share purpose. In an interview, she shared her thoughts.9 “I’m proud that we’ve developed a new paradigm of leadership development,” she said. “We call it Leading Thinking. Organizations have competency models that are about behaviors. That’s not the place to start. We’ve backed up to emphasize the thinking first. Without linking it all together, you don’t have a framework for developing yourself. It starts with a platform of being able to fully articulate your philosophy of living a full and complete life. From there you address your values and understand what’s essential to what you are. We help our leaders start with mindsets before moving to behaviors.

“We’ve heard program participants say things in their feedback such as ‘You’ve made me a better man’ and ‘This approach is making me the leader I’ve always wanted to believe in.’

“Our participants are inspired, which in turn, inspires others in their organizations,” Joyce said.

Beyond engaging participants to find and align their individual purposes, Brookings also helps leaders tap into their very reason for being in government service in the first place. This may also be their big P purpose, and most certainly their why. Joyce discussed how invigorating and inspiring this is for everyone involved in the program.

“When you connect people to their noble purpose, they’re more inspired and more inspiring,” she told me. “When we’re in a room of government leaders, we make the connection that they are part of a larger tapestry. The founders who convened in Philadelphia weren’t much different than the government leaders sitting in the room. There’s something so ennobling about realizing they are part of what makes this country unique, and that they are part of its history. Participants come back recharged, reenergized, and recommitted to make the Constitution truer. They see that what they do keeps achieving this dream of America.”

Brookings Executive Education is leading powerful, personal, purpose-filled conversations in government. If we can engage purpose in our largest institutions, we can do it anywhere! Most organizations have far more latitude than the large and complex federal government. Purpose is a fast track to inspiration, empowerment, and motivation. Every conversation you have where you’re pointing toward purpose has the possibility to change perspectives, options, and even lives. And doing it is a straightforward process.

Purpose is a shortcut to get people to a place where they’re most inspired, empowered, and motivated.

HELPING OTHERS FIND PURPOSE

When leaders think of purpose, they often conjure up beautifully crafted mission statements, with persuasive speeches to win hearts and minds so it catches on. But we can’t sell someone a purpose, just as we can’t push anyone into being inspired. We help someone find purpose by creating a space, and by being in the conversation. By engaging at this place, we act as a guide to find more purpose. Think of yourself as coaching around purpose, rather than managing to it.

In our interview, Wharton professor and bestselling author of Give and Take and Originals Adam Grant shared his own take on helping others to find purpose. He referred to a body of research in social psychology called “action identification theory,” which concludes that there are multiple levels of explanation we can use for any one event, ranging from specific details to abstract thoughts.10 The more abstract, or higher level, way we are able to view an event, the closer we are to the realm of purpose. Grant explains it this way, using our interview as an example:

Anything you do, you can look at several levels of analysis. I’m speaking, so I’m producing sound and moving lips. At the next level, I’m having a conversation. At the next level, I’m helping you write a book. At the loftiest level, I’m sharing knowledge with an audience. We identify our actions in terms of the process, and at the highest levels we’re finding a purpose. It’s more motivating to think of work in terms of purpose than process. A lot of what we have to do is process, and it’s hard to see the purpose all the time. It’s a huge role for leaders to be able to help others connect the dots—to show how one’s efforts connect to something that really matters.11

There are multiple levels of explanation to any event, ranging from specific details to meaningful thoughts. The higher up the ladder we go, the closer we get to purpose.

We coach others toward purpose by walking them up the ladder of this analysis. We don’t need to be directive—and we shouldn’t be. We’re helping them by guiding their thinking. Again, we’re coaching. This is what Brookings is doing with senior government leaders—providing a constructive, inspirational space for them to consider their highest callings for their work, which for some goes right up to the Constitution.

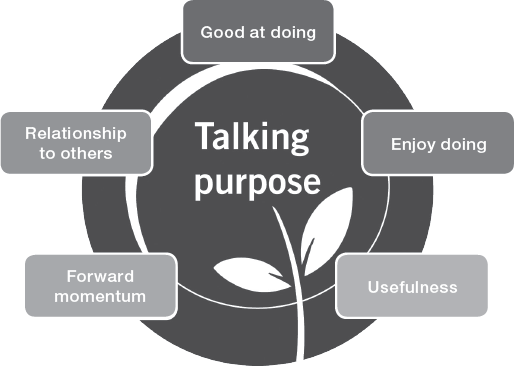

Questions are a perfect way to have purposeful conversations. They invite thinking. They gently expand perspective. But the type of question we ask also matters. We know from decades of research that people find internal motivation, inspiration, and purpose through consistent means—by doing what they’re good at and enjoy, feeling useful, being in relationship to others, and having a sense of agency that carries them forward.

Purpose exists at the place where we’re doing what we’re good at and enjoying it; feeling useful; in relationships with others; and feeling forward momentum.

Figure 10.1 provides a guide for how to engage around purpose. When all five of these elements are in our work, we’re at our most purposeful and inspired. While many of us won’t find all of them tomorrow, with some guidance, we should be able to move the needle forward and broaden our perspective.

Figure 10.1: How to Engage around Purpose

The rest of this chapter outlines suggestions for how to coach or counsel around each of these areas. They are fairly easy topics to bring up because people enjoy talking about them, at least on some level. In any one conversation, you can hit upon all of them or delve into one at a time.

GOOD AT DOING

When we’re doing activities that play to our strengths, we can sense a glide path to purpose. If we feel competent then we feel motivated, which leads us to work harder and with positivity, which only increases our aptitude. This doesn’t mean that the activity has to be effortless; it can take a lot out of us. A great musician must work hard to master the toughest compositions.

We all have strengths that, when applied to our work, generate a contented hum as the time passes. If we’re lucky, every day we do some work that incorporates our strengths. But in the crush of everything that we have to just get done, it’s all too easy to forget what we’re good at doing. By leading a conversation around competency, we can help guide others back to this place of strength, and open up new possibilities from there.

By leading a conversation around competency, we can help guide others back to this place of strength, and open up new possibilities from there.

Questions that guide to what another is good at doing:

![]() What work activities come easiest to you?

What work activities come easiest to you?

![]() What do you do as well as or better than anybody in your role?

What do you do as well as or better than anybody in your role?

![]() What do you take on because you know you’re the best person to do it?

What do you take on because you know you’re the best person to do it?

![]() For what actions have you consistently been complimented in your life?

For what actions have you consistently been complimented in your life?

ENJOY DOING

Hopefully we enjoy doing what we’re good at. But surprisingly often, this simply isn’t the case. A person is good at math so becomes an accountant—yet hates managing debits and credits all day. An engineer is promoted to management, but misses the artistry of product design. You get the point. Many people fall into careers that they’re good at doing, but don’t enjoy. This is why midlife career crises happen!

When we coach around enjoyment, we’re guiding others to a place where they can either find or rekindle what they love about work. Sometimes this leads to the discussion about a career change, but more likely, it doesn’t. There are aspects we like and don’t like about any position, but it all gets jumbled up in our monolithic J-O-B. We also have way more capability to adapt our duties than we may think. (In my experience, we talk ourselves out of even asking, but when we do, we get much of what we wanted.)

When we coach around enjoyment, we’re guiding others to a place where they can either find or rekindle what they love about work.

Questions that guide to what another enjoys doing:

![]() What are you doing that makes you lose track of time at work?

What are you doing that makes you lose track of time at work?

![]() If you could design your job any way you’d like, no restrictions, what would you spend your time doing?

If you could design your job any way you’d like, no restrictions, what would you spend your time doing?

![]() When you consider a high point in your career, what were you doing?

When you consider a high point in your career, what were you doing?

![]() What would you do even if you didn’t get paid to do it?

What would you do even if you didn’t get paid to do it?

USEFULNESS

If you’ve ever been assigned busy work, then you know why usefulness is related to purpose. When we feel that our work is going nowhere, it doesn’t matter how much we like it or are good at it; our labors still feel hollow. There’s inherent meaningfulness in doing something that’s useful—whether to a person, to a company, or to a goal.

There’s inherent meaningfulness in doing something useful.

The utility of our work can be obscured due to poor communication, changing corporate agendas, opaque management, or lots of other reasons. At one time or another, most of you have thought, “This is pointless, but I’ll do it because my boss asked for it.” I’ve heard this as high up as CEOs delivering information to the board. On the other hand, if we know that our work contributes to something important, we can overlook aspects that may not be ideal. Think of employees who—feeling passionate about the cause—work crazy hours to grow the start-ups where they work. Or stay-at-home parents who believe that raising their kids is their most important work, and sacrifice to do it.

Questions that guide to usefulness of another’s work:

![]() What’s most important about what you contribute?

What’s most important about what you contribute?

![]() How does your work help others or a larger cause?

How does your work help others or a larger cause?

![]() What’s the most critical thing you should be doing now?

What’s the most critical thing you should be doing now?

![]() What are the highest priorities for your life and how does your work fit into them?

What are the highest priorities for your life and how does your work fit into them?

FORWARD MOMENTUM

Purpose isn’t stagnant; it’s a movement toward something. Purpose has a direction, and it’s forward. It’s meaningful to help others move past the current state into a state of purpose that propels them. When people lose a sense of purpose, it’s often because they get trapped in the here and now, and can’t discern how to tap into the flow to take them to the next place in their lives and/or their careers.

Purpose has a direction, and it’s forward.

When we coach to identify forward momentum, we’re helping another ideate and create the future state. We’re showing how what she’s doing today will enhance her tomorrow. We’re connecting the dots so he can see why his labor will carry him forward—or to borrow from a prior example, why practicing the difficult music continues to make the musician even better.

Questions that guide to forward momentum:

![]() How’s your work today getting you closer to what you want for yourself?

How’s your work today getting you closer to what you want for yourself?

![]() What do you hope is possible for you, without setting limitations?

What do you hope is possible for you, without setting limitations?

![]() What could you do next with what you’re learning now?

What could you do next with what you’re learning now?

![]() What do you envision yourself doing in the coming months? In one year? Five years?

What do you envision yourself doing in the coming months? In one year? Five years?

RELATIONSHIP TO OTHERS

Finally, in nearly all instances, our purpose isn’t a solo act, but involves others. It may mean working as part of a larger team, running a group or a company, being around certain types of colleagues, or acting as a valued contributing voice. We may desire a particular type of manager who supports and guides us. Or the relationships outside of our work may be most important to us: being there for our families or interacting with a larger industry. When we bring the relationships into the conversation about purpose, then we acknowledge the large impact that they have on the meaning of our work.

It’s our purpose, but it exists in relationship to others.

The work we do can only be so meaningful. The people we do it for and with matter significantly. We often don’t think intentionally about the relationships that support our work, but rather, hope for the best and take what we get. Purpose-driven conversations are precisely the time to get others to think seriously about this key factor to their inspiration and motivation.

Questions that guide to relationships to others:

![]() What’s your ideal work environment?

What’s your ideal work environment?

![]() Describe your best working relationships.

Describe your best working relationships.

![]() How could your relationships enhance your work and broader life?

How could your relationships enhance your work and broader life?

![]() What would a culture of your favorite people look like?

What would a culture of your favorite people look like?

PURPOSE IS IDEAL, BUT THERE’S NO IDEAL PURPOSE

Engaging others at the high level of finding purpose may have sounded at first like a formidable undertaking and potentially even a rabbit hole. After all, what if you help people find their purpose, and it’s at another company? That is, of course, a possibility. But an even greater possibility is that you ignite a renewed passion for their work at their present company, with a leader (you) who inspired them to think bigger for themselves.

Great leaders do this every day. They continually check in to ensure that what a person does links to what a person wants to be. It’s that straightforward. Purpose doesn’t have to be about the largest life questions, but can be most effective at its most practical: helping others find meaning in the here and now. When we ask the right questions, we can coach others into finding the right answers for themselves for how to do work they’re good at and enjoy, that’s worthwhile and moves them forward, and that helps them in the relationships that matter. While we may not be lucky enough to have all of these at the same time, just engaging in the question helps to move each aspect further. What we practice gets stronger.

Purpose doesn’t have to be about the largest life questions, but can be most effective at its most practical: helping others find meaning in the here and now.

FROM CHAPTER 10

![]() Having an inspired purpose is important to any level of professional. Leaders should learn to engage their people on purpose, which helps to increase well-being and goal progression, as well as vitality, positivity, and life satisfaction. Purpose-oriented people are more likely to be leaders.

Having an inspired purpose is important to any level of professional. Leaders should learn to engage their people on purpose, which helps to increase well-being and goal progression, as well as vitality, positivity, and life satisfaction. Purpose-oriented people are more likely to be leaders.

![]() Purpose exists on multiple levels from one’s life purpose to the purpose of a discrete work project. An inspiring place for leaders to play is the middle—helping another to determine work that’s meaningful for where that person is at this moment in his or her life and career.

Purpose exists on multiple levels from one’s life purpose to the purpose of a discrete work project. An inspiring place for leaders to play is the middle—helping another to determine work that’s meaningful for where that person is at this moment in his or her life and career.

![]() Having a purpose is linked to inspiration and intrinsic motivation. People are inspired by something, and when you engage others in purpose, you create the impetus.

Having a purpose is linked to inspiration and intrinsic motivation. People are inspired by something, and when you engage others in purpose, you create the impetus.

![]() There are multiple levels of analysis for any situation, from the process (“I’m reading the words on the page”) to the purpose (“I’m learning to inspire others”). Engaging in purposeful conversations involves walking people up this ladder of sense-making.

There are multiple levels of analysis for any situation, from the process (“I’m reading the words on the page”) to the purpose (“I’m learning to inspire others”). Engaging in purposeful conversations involves walking people up this ladder of sense-making.

![]() To guide others toward their purpose, explore what they’re good at doing, enjoy doing, find useful, has forward-momentum, and builds relationships to others.

To guide others toward their purpose, explore what they’re good at doing, enjoy doing, find useful, has forward-momentum, and builds relationships to others.