CHAPTER 2

Clarify Values

WHO ARE YOU? This is the first question your constituents want you to answer. Finding that answer is where every leadership journey begins.

When Alex Anwar was hired as director of a new business unit at Labo America, he faced resentment from many within the company because they felt that he was too young and inexperienced to manage such a diverse group and product portfolio.1 Because many of the units were siloed and polarized, a widespread question was whether he would be the kind of leader who would bring people together toward a common goal. Alex’s first step was to communicate his values to the team. He circulated an email introducing himself, not as a manager, but as a fellow employee of the company charged with a difficult task. Instead of telling everyone what he wanted out of them, he stated clearly what values and performance criteria he demanded of himself every day. In teaching his value set, Alex ensured that people would be better prepared to understand his actions and the reasoning behind certain decisions. They were able to connect the outcome with a value (for example, hard work).

In an all-hands meeting later that week, Alex provided a few examples of cases in which he exercised his core values of honesty and sincerity, discussing how he handled a particular problem with a customer. He took his constituents through the issue as though narrating a story. He subsequently used this style of storytelling every time he made a case for how certain company situations were to be handled. By making these lessons easy to relate to, values centered, and personal, he helped people both understand and retain the intended lesson. As one of his direct reports explained, “Alex made his values understood through clearly communicating and providing contexts that would aid in their retention. He put all the values into his own words, and thus gave us a clear idea about the kind of person he was.”

The Personal-Best Leadership Experience cases we’ve collected are, at their core, the stories of individuals who, like Alex, were clear about their personal values and understood how this clarity gave them the courage to navigate difficult situations and make tough choices. People expect their leaders to speak out on matters of values and conscience. But to speak out, you have to know what to speak about. To stand up for your beliefs, you have to know the beliefs you stand for. To walk the talk, you have to have a talk to walk. To do what you say, you have to know what you want to say. To earn and sustain personal credibility, you must first be able to clearly articulate deeply held beliefs.

Model the Way is the first of The Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership we discuss in this book, and one of the commitments you have to make in order to effectively Model the Way is to Clarify Values. In beginning your leadership journey, it’s essential that you

- FIND YOUR VOICE

- AFFIRM SHARED VALUES

To become a credible leader, you first have to comprehend fully the deeply held beliefs—the values, standards, ethics, and ideals—that drive you. You have to freely and honestly choose the principles you will use to guide your decisions and actions. Then you have to genuinely express yourself. You have to authentically communicate your beliefs in ways that uniquely represent who you are.

However, leaders aren’t just speaking for themselves when they talk about the values that should guide decisions and actions. When leaders passionately express a commitment to quality or innovation or service or some other core value, those leaders aren’t just saying, “I believe in this.” They’re also making a commitment for an entire organization. They’re saying, “We all believe in this.” Therefore, leaders must not only be clear about their personal guiding principles but also make sure that there’s agreement on a set of shared values among everyone they lead. And they must hold others accountable to those values and standards.

FIND YOUR VOICE

“What is your leadership philosophy?” What would you say if someone asked you this question? Are you prepared right now to say what it is? If you aren’t, you should be. And if you are, you need to reflect on it daily.

Before you can become a credible leader—one who connects what you say with what you do—you first have to find your voice. If you can’t find your voice, you’ll end up with a vocabulary that belongs to someone else, mouthing words that were written by some speechwriter or mimicking the language of some other leader who’s nothing like you at all. If the words you speak are not your words but someone else’s, you will not, in the long term, be able to be consistent in word and deed. You will not have the integrity to lead.

To find your voice, you have to explore your inner self. You have to discover what you care about, what defines you, and what makes you who you are. You can be authentic only when you lead according to the principles that matter most to you. Otherwise you’re just putting on an act. Consider Casey Mork’s experience with an internal start-up business that never got off the ground:

First, our manager never had a true voice, as he never had the courage to pronounce solutions or suggestions beyond what our three (never agreeing) directors input into each decision. Oftentimes it felt like he acted as a simple conduit for mixed messages from above … without his own personal voice defining a clear road for us to travel. This made it very difficult for the group to focus on a defined set of tasks connected to goals.

Second, an outcome of the above was that we had no specific organizational values to live by. Sure we all knew the company mission, and transferred in corporate values from our previous groups (inside the same company), but he never went beyond the ordinary in defining values for our business. Our customers were different, and so how should we treat them differently than the rest of the company? We spent a lot of money pampering our customers; how would this apply to managing our expense accounts? Seemingly simple values went undefined and as a result were exploited by some team members.

As could have been predicted, Casey says, this lack of clarity and consistency in values at the top resulted in little internal cohesion and focus, and the company failed to generate a favorable customer experience or positive business results. In contrast, Josh Fradenburg, founder of Mindful Measures says that it was his values that drove the products that he brought to market. “It was really the values that formed the organization, rather than the organization forming the values,” he recounts.

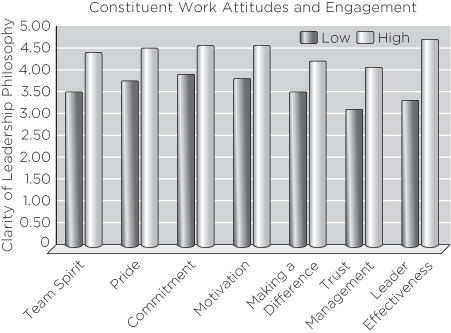

When we ask leaders how clear they are about their leadership philosophy, those who fall into the top 10 percent on this leadership behavior have quite different work attitudes than their counterparts in the bottom 10 percent. Their overall attitudes toward the workplace are significantly more positive. When asked to rate their own effectiveness as a leader, the scores of those who are clear about their leadership philosophy are 25 percent higher than those who report being not very clear about their leadership philosophy.

The impact that the leader’s clarity of leadership philosophy has on his or her constituents is even more dramatic, as shown in Figure 2.1. When asked how effective the leader is, the scores from those working with leaders who are seen as being clear about their leadership philosophy are more than 40 percent higher than those scores received from constituents who view leaders as not very clear about their leadership philosophy. There are statistically significant differences between these two groups of constituents on a variety of important dimensions. For example, feeling a sense of team spirit, feeling proud about the organization, feeling committed to the organization’s success, being willing to work extra hard to meet organizational objectives, and levels of trust all differ significantly. Leaders who have a clear leadership philosophy are nearly 30 percent more likely to be trusted by their constituents than those unclear about their leadership philosophy.

FIGURE 2.1 The Impact of Leadership Philosophy Clarity on Constituent Work Attitudes and Engagement

The evidence is clear: to be the most effective, every leader must learn to find the voice that represents who he or she is. When you have clarified your values and found your voice, you will also find the inner confidence necessary to express ideas, chose a direction, make tough decisions, act with determination, and be able to take charge of your life rather than impersonating others.

Let Your Values Guide You

Milton Rokeach, one of the leading scholars in the field of human values, referred to a value as an enduring belief. He noted that values are organized into two sets: means and ends.2 In the context of our work on leadership, we use the term values to refer to here-and-now beliefs about how things should be accomplished—what Milt calls means values. We will use vision in Chapters Four and Five when we refer to the long-term ends values that leaders and constituents aspire to attain. Leadership requires both. When sailing through the turbulent seas of change and uncertainty, crew members need a vision of the destination that lies beyond the horizon; they also need to understand the principles by which they must navigate their course. If either of these is absent, the journey is likely to end with the crew lost at sea.

Values influence every aspect of your life: your moral judgments, your responses to others, your commitments to personal and organizational goals. Values set the parameters for the hundreds of decisions you make every day, consciously and subconsciously. Options that run counter to your value system are seldom considered or acted on; and if they are, it’s done with a sense of compliance rather than commitment.

Values constitute your personal “bottom line.” They serve as guides to action. They inform the priorities you set and the decisions you make. They tell you when to say yes and when to say no. They also help you explain the choices you make and why you made them. If you believe, for instance, that diversity enriches innovation and service, then you should know what to do if people with differing views keep getting cut off when they offer fresh ideas. If you value collaboration over individualistic achievement, then you’ll know what to do when your best salesperson skips team meetings and refuses to share information with colleagues. If you value independence and initiative over conformity and obedience, you’ll be more likely to challenge something your manager says if you think it’s wrong.

All of the most critical decisions a leader makes involve values. For example, values determine how much emphasis to place on the immediate interests of the customer or the long-term interests of the company, how to apportion time between family and organizational responsibilities, and what behaviors to reward or discourage. In turn, these decisions have critical organizational impact. Indeed, in these turbulent times, having a set of deeply held values allows leaders to focus and make choices among a plethora of competing beliefs, paradigms, and interests.

Paul di Bari’s operations section within the engineering services group took on the new responsibility for the physical security of the VA Palo Alto Health Care System’s 2.2-million-square-foot facility. Along with the responsibility of hiring a new technician to manage this system, Paul was also taking on a new contractor relationship. Before starting any more projects, Paul called a meeting with the new technician and contractor to figure out the status of the current access system, any open projects, and any projects on the horizon. Paul used this meeting to vocalize his intentions about how the newly developed team would work, his vision moving forward, and his expectations for all parties. His values on project timelines, preparations, submittals, and execution would require more detailed attention than in the past and would also, he hoped, create a new sense of accountability. Paul explained,

If I was going to pay large sums of money for parts and services, then I had expectations for the quality of the deliverable, which were far higher than the previous regime. These higher standards of quality were necessary to fix the system and to make it operate at a high level. I began to personally inspect the work of the contractor as we completed six open projects. During this time, I was also training our new technician and establishing expectations of project management (for example, statements of work, pricing quotes, communication, workmanship, and the final product) that he would need to carry forth. It was imperative to the long-term success of this program and this new team that I clearly explained what my values were, my project management style and expectations.

Paul had to find his voice as a leader by clearly stating his leadership principles and the accompanying management goals and objectives. At the beginning of the project, Paul met with the contractor and his new technician to communicate these in the context of the security access system. By clearly defining his standards, he was establishing a baseline for future performance and also a measuring block on which to base accountability. “It would have been very easy for me,” Paul said, “to sit back and supervise the program from afar, but in order to earn the trust and respect of both people involved, I had to establish a sense of trust through my work ethic.” Because Paul was clear about his own values, he found it relatively easy to talk about values and subsequently to use them in setting standards and expectations. This tone at the top from Paul provided guidelines for how his constituents would subsequently act and make decisions.

As Paul’s experience illustrates, values are guides. They supply you with a compass by which to navigate the course of your daily life. Clarity of values is essential to knowing which way is north, south, east, and west. The clearer you are about your values, the easier it is for you and for everyone else to stay on the chosen path and commit to it. This kind of guidance is especially needed in difficult and uncertain times. When there are daily challenges that can throw you off course, it’s crucial that you have some signposts that tell you where you are.

Say It in Your Own Words

People can speak the truth only when speaking in their own true voice. The techniques and tools that fill the pages of management and leadership books—including this one—are not substitutes for who and what you are. Once you have the words you want to say, you must also give voice to those words. You must be able to express yourself so that everyone knows that you are the one who’s speaking.

You’ll find a lot of scientific data in this book to support our assertions about each of The Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership. But keep in mind that leadership is also an art. And just as with any other art form, leadership is a means of personal expression. To become a credible leader, you have to learn to express yourself in ways that are uniquely your own. Which is exactly what Andrew Levine did, and in the process helped his colleague Pranav Sharma be able to do the same.

Andrew is a head mentor at the Young Storytellers Foundation (YSF), a nonprofit organization in the United States that provides a creative outlet to fifth-graders whose public schools do not have the budget for creative arts programs. He is passionate about and committed to providing a classroom atmosphere that pushes the imaginations of the kids they mentor, and he cares deeply for all the YSF volunteers. According to one of those volunteers, Pranav Sharma, Andrew’s personal values fit comfortably with the values articulated in YSF’s mission statement. Pranav told us how Andrew influenced him: “He had a unique voice among the mentors. His example led me to exhibit values he shared with the organization. He helped me understand what it meant to the kids to have a unique voice.”

Pranav was paired with a fifth-grader named Rachel, and was tasked to guide her in writing an original story in a ten-page screenplay format, but he was having trouble getting Rachel to focus on her story. Whereas other mentors were making progress on their kids’ stories, Pranav felt that Rachel was not very motivated. The fact that Pranav was absent a couple of times over the eight-week program because of the demands from his workplace didn’t help the situation. Andrew was noticeably frustrated with Pranav and a few other mentors’ seeming lack of interest in the program. He took two steps to remedy the situation. First, he reminded the delinquent mentors why they had joined the program. He talked about why he was loyal to the program. He asked them to leave the program if they were not making YSF a priority, which would be evidenced by future absences. Second, he asked the volunteers to look at the program through the perspective of the fifth-grader. What are the kids looking for from their mentors? He suggested that the volunteers stop worrying about whether they were qualified to mentor or whether the kids would like them. All that was required, Andrew explained, was to be present and to talk to them. Pranav got the point.

Andrew was right. He was asking us to affirm our shared values and find our voice. What Andrew was doing was asking us to reexamine the reasons we joined YSF. He wanted us to be vested in YSF’s values, which included words like loyalty, commitment, passion, and patience. He wanted us to build a relationship with the kids by talking to them. The only way to make a unique difference in a kid’s life was to find my own voice. I had to find my voice if I was to make an indelible impression on my mentee.

So Pranav gave it a shot. He reflected on the reasons he had originally wanted to join YSF, which involved giving back creatively to the community. He had wanted to join a nonprofit organization that valued loyalty. He said,

Finding my voice was not easy. I talked without pretense, allowing Rachel to guide the conversation. It was difficult at first, but the enthusiasm in Rachel’s eyes encouraged me to continue to establish my own voice and my own words. The result was a happy child who was proud of her original story. At the end of the program, she gave me a very creative thank-you card highlighting me as the best mentor she had had. I was proud of her.

The lesson here is that Andrew gave Pranav, and all the other mentors, time to discover how their personal values meshed with those of YSF. By telling them his own story of why he was passionate about becoming a mentor at YSF, he helped them find the words to express their own reasons for caring about YSF, its mission, and especially the children. Andrew didn’t tell them what to believe; he told them about his own beliefs and asked them to find in their own values their reasons for being involved with the organization. Through this reflection, they discovered their own voice and found the words necessary to reach kids like Rachel and help them find their way.

Leaders like Andrew and Pranav understand that you cannot lead through someone else’s values or someone else’s words. You cannot lead out of someone else’s experience. You can lead only out of your own. Unless it’s your style and your words, it’s not you—it’s just an act. People don’t follow your position or your technique. They follow you. If you’re not the genuine article, can you really expect others to want to follow? To be a leader, you’ve got to awaken to the fact that you don’t have to copy someone else, you don’t have to read a script written by someone else, and you don’t have to wear someone else’s style. Instead, you are free to choose what you want to express and the way you want to express it. In fact, you have a responsibility to your constituents to express yourself in an authentic manner, in a way they would immediately recognize as yours.

Find Commitment Through Clarifying Values

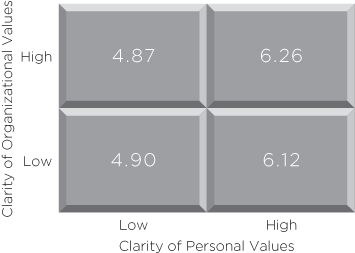

It’s one thing to expect leaders to be clear about their values and beliefs, but it’s another to prove that it really matters that they are. What’s the evidence for this assertion? How much difference does being clear about values really make? We set out to empirically investigate the relationship between personal values clarity, organizational values clarity, and a variety of outcomes, such as commitment and job satisfaction. Surveying a large sample of managers in the early 1980s, and another sample of managers nearly two decades later, revealed few differences in the findings.3 The results of our research clearly indicate that clarity of personal values makes a significant difference in behavior at work.

Managers were asked about the extent of their clarity around their personal values as well as the values of their organization. They were also asked about their level of commitment to their organization, how proud they were to tell others they worked in their organization, their level of motivation and productivity, their job satisfaction, and the like. As you can see in Figure 2.2, the highest levels of commitment are found where personal values are the clearest. Clarity about personal values was consistently more significant in accounting for positive workplace attitudes and levels of engagement than was clarity around organizational values.4

FIGURE 2.2 The Impact of Values Clarity on Commitment

The people who are clear about their personal beliefs but can’t recite the corporate credo are significantly more likely to stick around and work hard than those people who’ve heard the organizational litany but have never listened to their own inner voice. In other words, personal values drive commitment. Personal values are the route to motivation and productivity.

How can this be? How can people who are very clear about their own values be committed to a place that has never affirmed or posted its organizational values? Think about it. Have you ever had the feeling, “This place is not for me?” Have you ever walked into a place, immediately gotten the sense, “I don’t belong here,” and just walked right out? In contrast, have you ever just known that you belong, that you can be yourself, and felt “This is the right place for me”? Of course you have. Everyone has had those experiences.

It’s the same in the workplace. There comes a point when you just know whether it is or isn’t a good fit with your values and beliefs, even if there was no lecture on the organization’s values. You won’t stick around a place for very long when you feel in your heart and in your soul that you don’t belong. This is why people’s years of managerial experience and hierarchical level help explain differences in the extent of personal values clarity, whereas such factors as gender, educational level, and functional discipline do not.5 The most talented people, no matter their age or background, gravitate to companies where they can look forward to going to work each day because their values “work” in that organizational setting. Julie Sedlock, group vice president for operations at Aéropostale, a global specialty retailer of casual apparel and accessories, echoes this observation: “I love to come to work here. I can’t think of a day in twenty years that I didn’t want to wake up and go to work.” She explains that when you share the company’s values, you “want to come to work, work hard, and achieve the goals that the organization has set.”

Workplace and organizational commitment are based on alignment with personal values and who you are and what you are about. People who are clearest about personal values are better prepared to make choices based on principle—including deciding whether the principles of the organization fit with their own!

AFFIRM SHARED VALUES

Leadership is not simply about your own values. It’s also about the values of your constituents. Just as your own values drive your commitment to the organization, their personal values drive their commitment. Your constituents will be significantly more engaged in a place where they believe they can stay true to their beliefs. Although clarifying your own values is essential, understanding the values of others and building alignment around values that everyone can share are equally critical.

Shared values are the foundational pillars for building productive and genuine working relationships. Credible leaders honor the diversity of their many constituencies, but they also stress their common values. Leaders build on agreement. They don’t try to get everyone to be in accord on everything. This goal is unrealistic, perhaps even impossible. Moreover, to achieve it would negate the very advantages of diversity. But to take the first step and then a second and then a third, people must have some common core of understanding. After all, if there’s no agreement about values, then what exactly are the leader and everyone else going to model? If disagreements over fundamental values continue, the result is intense conflict, false expectations, and diminished capacity.6 Leaders ensure that everyone is aligned through the process of affirming shared values––uncovering, reinforcing, and holding one another accountable to what “we” value.

Hilary Hall told us about how her manager helped people examine their own values and how this built a foundation of shared values that resulted in a spirit of camaraderie and common purpose. At General Electric, Hilary was on a multinational internal audit team, which consisted of a German, two Americans, a Belarusian, and an Indian:

At the beginning of the audit, before we even began work, our manager had us all complete a questionnaire, which included topics such as where we grew up, favorite food, hobbies, and so on. There were also questions that dug a little deeper and asked us about the type of work we liked and did not like, how we liked to work, the role we usually played on teams, and what we respected in managers and teammates. After completing the questionnaires individually, we gathered as a group and shared our responses.

At the time, I thought of the exercise as a team icebreaker, a chance for us to get to know one another and build a sense of camaraderie, especially since we came from different corners of the globe. Why else would I need to know that Matt enjoys eating Mexican food, or likes to kick around ideas before having to make a decision? Reflecting on the experience now, I understand that the exercise was more than just an icebreaker; our manager was aligning the team around a common set of values––both personal and professional––and showing the team what was important to him, too. This was especially imperative since internal audit work was often stressful, extremely deadline oriented, and required us to be at the work site for two weeks at a time. It was a demanding work environment, and I believe our success as individual auditors was contingent on our success as a team, which begins with mutual respect and trust.

Hilary was clear that if the team members had not aligned themselves around common values, their effectiveness as a team, as well as their manager’s credibility, would have suffered. They could have easily lost touch with one another and worked according to their own individual standards, which would have resulted in uneven motivation and commitment toward common work goals. “From this experience,” says Hilary,

I have learned that a good leader takes the time to break the ice and know his or her team on a personal level, but a great leader goes one step further and learns about each person’s values, how they build trust, and what is core to their motivation and drive. They then share the team’s values, as well as their own, and align the team around a strong focal point for working together toward a shared goal (or goals).

Research confirms Hilary’s experience. Organizations with a strong corporate culture based on a foundation of shared values outperform other firms by a huge margin. Their revenue and rate of job creation grow faster, and their profit performance and stock price are significantly higher. Furthermore, studies of public sector organizations support the importance of shared values to organizational effectiveness. Within successful agencies and departments, considerable agreement, as well as intense feeling, is found among employees and managers about the importance of their values and about how those values should best be implemented.7

In our own research, we’ve found that shared values make a significant and positive difference in work attitudes and commitment.8 For instance, shared values

- Foster strong feelings of personal effectiveness

- Promote high levels of company loyalty

- Facilitate consensus about key organizational goals and stakeholders

- Encourage ethical behavior

- Promote strong norms about working hard and caring

- Reduce levels of job stress and tension

- Foster pride in the company

- Facilitate understanding about job expectations

- Foster teamwork and esprit de corps

Periodically taking the organization’s pulse to check for values clarity and consensus is well worthwhile. It renews commitment. It engages the institution in discussing values (such as diversity, accessibility, sustainability, and so on) that are more relevant to a changing constituency. Once people are clear about the leader’s values, about their own values, and about shared values, they know what’s expected of them and how they can count on others. With this clarity, they can manage higher levels of stress and better handle the often conflicting demands of work and their personal lives.

Give People Reasons to Care

Important as it is that leaders forthrightly articulate the principles for which they stand, the values leaders espouse must be consistent with the aspirations of their constituents. Leaders who advocate values that aren’t representative of the collective won’t be able to mobilize people to act as one. There has to be a shared understanding of what’s expected. Leaders must be able to gain consensus on a common cause and a common set of principles. They must be able to build and affirm a community of shared values.

It’s vitally important that leaders and constituents arrive at consensus on shared values, because once they are articulated, those values become a pledge to employees, customers, clients, business partners, and other constituents. They are a promise to people that everyone in the organization will do what the values prescribe. Regardless of whether the organization is a team of two, an agency of two hundred, a school of two thousand, a company of twenty thousand, or a community of two hundred thousand, shared values are the ground rules for making decisions and taking action. Unless there’s agreement on these principles, leaders, constituents, and their organizations risk losing credibility.

Recognition of shared values provides people with a common language. Tremendous energy is generated when individual, group, and organizational values are in synch. Commitment, enthusiasm, and drive are intensified. People have reasons for caring about their work. When individuals care about what they are doing, they are more effective and satisfied. They experience less stress and tension. Shared values are the internal compasses that enable people to act both independently and interdependently.

Nicole Matouk was a student records analyst at Stanford Law School when the school implemented a major transition from the semester to the quarter system. Because of all the preparations that needed to be made in advance of the transition (such as overhauling the computer systems) and because of the quarter system itself, which required an additional term of work, by the end of the school year, everyone was exhausted and in need of encouragement. The associate dean sent an email to the people working in the registrar’s office, asking for their feedback about the transition and inviting them to meet with her over coffee and talk informally about the transition process.

Everyone had the opportunity to speak about the topics he or she felt strongly about, and all were given equal and ample time to express themselves. No one felt pressured, and the staff felt free to express their opinions without any fear of retribution. The dean asked questions about how they could make their jobs more efficient and which new systems could be implemented to make procedures easier for both the students and the staff. Nicole went on to explain that

The dean’s questions kept us from taking a bath in the negative emotions we were feeling, and they helped us refocus on our goals as an office. She used these questions to affirm our shared values. The dean didn’t have to struggle to think of the questions she wanted to ask, or how she would connect what we were discussing to our goals; her values were guiding her questions. As we talked, I could tell she was leading me in a certain direction, but it didn’t seem manipulative. This was so much more powerful to me than reading about the values in the handbook. I was generating the answers to her questions, so I felt this is what I believe, not just what I am supposed to agree with.

Not only did this meeting help our team to individually generate answers that were in line with our values and the office’s values, it helped us to affirm our shared values as an office. We came out of that meeting more united and with the knowledge that we were all working to achieve the same thing, instead of pulling against each other for time and attention.

Nicole’s experience reaffirms that people are more loyal when they believe that their values and those of the organization are aligned. The quality and accuracy of communication, and the integrity of the decision-making process, increase when people feel part of the same team. They are more creative because they become immersed in what they are doing. Our research, along with the findings of others, clearly reveals that when there’s congruence between individual values and organizational values, there’s significant payoff for leaders and their organizations.9

We found that nearly two-thirds of people surveyed felt that organizations, and their leaders, should be spending more time talking about values.10 The Trustmark Companies take this message seriously. They put their entire organization (twenty-five hundred employees) through an internal leader-led “Values Experience” during which people had the chance to think about their values and reflect on how their values guided their actions.11 Feedback from this experience was so positive that Trustmark continues to give people the opportunity to share their values in unique ways. For example, on each floor of the company atrium, they post yards and yards of white paper for employees to write about, draw, and otherwise depict their values. Trustmark also instituted a “WeekEND Message” in which senior leaders throughout the organization volunteer to write an article to share. Each Friday, via email, they convey their thoughts and ideas, focused on their top five values. Leaders at every level are reaching out to others with stories that speak to their values.

Through conversations and discussions, like those at Trustmark, leaders renew commitment by reminding people why they care about what they are doing, and these exchanges reinforce feelings that everyone is on the same team (especially critical in distributed workplaces). Once people are clear about the leader’s values, about their own values, and about shared values, they know what’s expected of them. This clarity enriches their ability to make choices, enables them to better handle stressful situations, and enhances understanding and appreciation of the choices made by others.

Forge Unity, Don’t Force It

When leaders seek consensus around shared values, constituents are more positive. People who report that their senior managers engage in dialogue regarding common values feel a significantly stronger sense of personal effectiveness than individuals who feel that they’re wasting energy trying to figure out what they’re supposed to be doing.

Erika Long, HR manager for Procter & Gamble (P&G), started with the company as an intern and was immediately impressed with how leaders demonstrated their values and the core principles of the company in every decision they made. She says,

Leaders at P&G are constantly affirming these values. Anytime they are faced with a difficult decision, they will look to the PVP [the company’s Purpose, Values, and Principles] to guide their actions. I met with the director of sales for the Hong Kong and Taiwan regions. I asked him, how does he make sure he is always making the right business decisions? He said, simply, “I look to the PVP. It guides the way I do business. If I am put in a position that is in conflict with those guidelines, I simply don’t do it.”

Erika says that “people who work at P&G are proud to say so, and everyone feels they are part of something special. Their core values align with those of the organization.” When people are unsure or confused about how they should operate, they tend to drift, turn off, and depart. The energy that goes into coping with, and possibly fighting about, incompatible values takes its toll on both personal effectiveness and organizational productivity.

“What are our basic principles?” and “What do we believe in?” are far from simple questions. One study reported 185 different behavioral expectations about the value of integrity alone.12 Even with commonly identified values, there may be little agreement on the meaning of values statements. The lesson here is that leaders must engage their constituents in a dialogue about values. A common understanding of values emerges from a process, not a pronouncement.

This is precisely the experience of Charles Law, who at American Express was assigned to lead the launch of a marketing campaign with a team of six colleagues of different ethnicities and business functions. At first, progress was slow, as frequent conflicts drove down team morale. Each team member was focused on his or her own goals, without considering the interests of others. Differences between them led to mistrust, and worse yet, according to Charles, he had the least experience of anyone in the group, so team members were skeptical about his leadership competency.

Charles saw that the team needed to agree on a shared set of values in order to function well. He noted that it was not so important what the particular value was called or labeled but that everyone agreed on the importance and meaning of the values. One of his initial actions was to bring people together just for that purpose, so that they could arrive at shared understandings of what their key priorities and values were and what these meant in action. He sat down and listened to each team member individually, and reported about everyone’s opinions at their next group meeting. He encouraged open discussions and worked through any misunderstandings.

The last thing Charles wanted them to feel was that his values were being imposed on them. So each person talked about his or her own values and the reasoning behind them. In this manner, they were able to identify as a group the common values that were important. “With a set of shared values, created with everyone’s consent,” Charles explained, “everyone strived to work together as a team toward success. Shared values created a positive difference in work attitudes and performance. My action made my colleagues work harder, emphasized teamwork and respect of each other, and resulted in better understanding of each other’s capabilities to meet appropriately set mutual expectations.”

Charles understood that leaders can’t impose their values on organization members. Instead they must be proactive in involving people in the process of creating shared values. Imagine how much ownership of values there can be when leaders actively engage a wide range of people in their development. Shared values are the result of listening, appreciating, building consensus, and resolving conflicts. For people to understand the values and come to agree with them, they must participate in the process: unity is forged, not forced.

For values to be truly shared, they must be more than advertising slogans. They must be deeply supported and broadly endorsed beliefs about what’s important to the people who hold them. Constituents must be able to enumerate the values and have common interpretations of how those values will be put into practice. They must know how their values influence the way they do their own jobs and how they directly contribute to organizational success.

Jade Lui described an incident early in her career in which the managing director, in Jade’s words, “taught us to model the company’s values.” When someone discovered that an applicant had withheld critical information from a client, although it was not information that the client had requested, the question arose whether to share that information and possibly lose the deal. Although the situation occurred during a particularly difficult financial time for their company, the response from their leader about what to do didn’t come as a surprise to Jade because it embodied the “core values espoused by the company.” He told them that

first and foremost, we should be honest with our clients. If we concealed the truth from the client, we would tarnish our reputation of service excellence. Further, we are committed to long-term partnerships with our clients. Sacrificing revenue for the short term in exchange for the client’s appreciation of our integrity, excellence, and commitment would bring more business in the long run. He continued to reassure that everyone in the company would work together to survive the temporary business downturn.

Having everyone on the same page when it comes to operating principles (values) ensures consistency in words and deeds for everyone, boosting in turn not just individual credibility but organizational reputation. Jade notes that not only is that client still one of their company’s most loyal partners, but “the lessons learned from my managing director’s decision are still firmly engraved in my mind.” She has subsequently “taught the next generation of staff the same shared values.”

A unified voice on values results from discovery and dialogue. Leaders must provide a chance for individuals to engage in a discussion of what the values mean and how their personal beliefs and behaviors are influenced by what the organization stands for. Leaders must also be prepared to discuss values and expectations in the recruitment, selection, and orientation of new members. Better to explore early the fit between individuals and their organization than to have members find out at some key juncture that they’re in serious disagreement over matters of principle.

TAKE ACTION

TAKE ACTION- Examine your past experiences to identify the values you use to make choices and decisions.

- Answer the question, What is my leadership philosophy?

- Articulate the values that guide your current decisions, priorities, and actions.

- Find your own words for talking about what is important to you.

- Discuss values in various recruitment, hiring, and on-boarding experiences.

- Help others articulate why they do what they do, and what they care about.

- Provide opportunities for people to talk about their values with others on the team.

- Build consensus around values, principles, and standards.

- Make sure that people are adhering to the values and standards that have been agreed on.

Notes

1. This example was provided by Gautam Aggarwal.

2. M. Rokeach, The Nature of Human Values (New York: Free Press, 1973), 5.

3. B. Z. Posner, “Values and the American Manager: A Three-Decade Perspective,” Journal of Business Ethics 91, no. 4 (2010): 457–465.

4. B. Z. Posner and W. H. Schmidt, “Values Congruence and Differences Between the Interplay of Personal and Organizational Value Systems,” Journal of Business Ethics 12 (1992): 171–177. See also B. Z. Posner, “Another Look at the Impact of Personal and Organizational Values Congruency,” Journal of Business Ethics 97, no. 4 (2010): 535–541.

5. Posner, “Another Look.”

6. C. Daniels, “Developing Organizational Values in Others,” in Leadership Lessons from West Point, ed. D. Crandall (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007), 62–87.

7. See, for example, A. Rhoads and N. Shepherdson, Build on Values: Creating an Enviable Culture That Outperforms the Competition (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2011); R. C. Roi, Leadership, Corporate Culture and Financial Performance, doctoral dissertation, University of San Francisco, 2006; and J. P. Kotter and J. L. Heskett, Corporate Culture and Performance (New York: Free Press, 1992).

8. See, for example, B. Z. Posner, W. H. Schmidt, and J. M. Kouzes, “Shared Values Make a Difference: An Empirical Test of Corporate Culture,” Human Resource Management 24, no. 3 (1985): 293–310; B. Z. Posner, W. A. Randolph, and W. H. Schmidt, “Managerial Values Across Functions: A Source of Organizational Problems,” Group & Organization Management 12, no. 4 (1987): 373–385; B. Z. Posner and W. H. Schmidt, “Demographic Characteristics and Shared Values,” International Journal of Value-Based Management 5, no. 1 (1992): 77–87; B. Z. Posner, “Person-Organization Values Congruence: No Support for Individual Differences as a Moderating Influence,” Human Relations 45, no. 2 (1992): 351–361; and B. Z. Posner and R. I. Westwood, “A Cross-Cultural Investigation of the Shared Values Relationship,” International Journal of Value-Based Management 11, no. 4 (1995): 1–10.

9. Posner, “Another Look.”

10. Posner, “Values and the American Manager.”

11. This example was provided by Jo Bell and Renee Harness.

12. R. A. Stevenson, “Clarifying Behavioral Expectations Associated with Espoused Organizational Values,” doctoral dissertation, Fielding Institute, 1995.