3

ALL THE FISH IN THE SEA

Ask any first-time entrepreneur “Who’s your ideal customer?” and the answer you’ll most likely hear is an enthusiastic “Everyone!” The enterprise version of this enthusiasm is the presumption that new products must satisfy all existing customers. Traditional market research methods depend on measuring customer input from thousands or even millions of people. But breakthrough innovation doesn’t happen that way. Such practices work only in existing, well-understood markets.

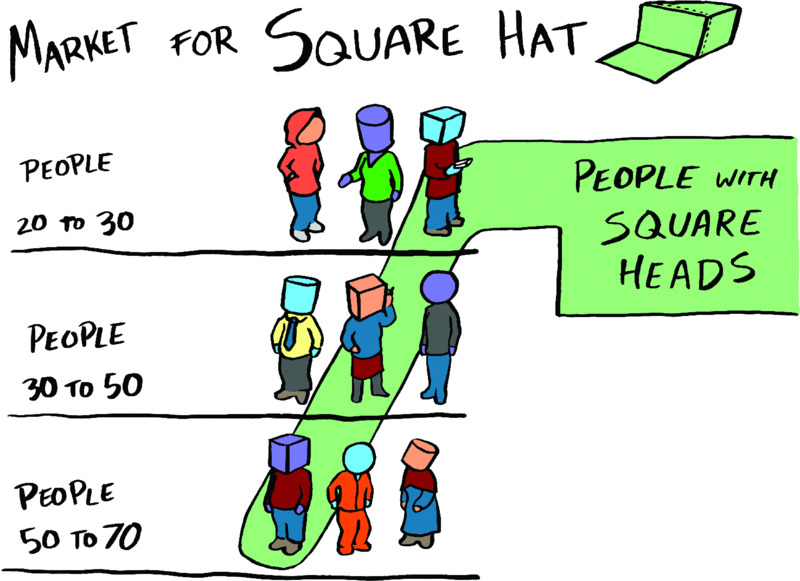

Those who are a bit more savvy might tackle segments of the market, but unfortunately, they often do so in the old-school way, categorizing customers by product type, demographics, or vertical industry, like financial services. The problem with this research is that it doesn’t get to the needs of the customer. It’s a way to classify, but not to learn.

We want to group customers based on need. For instance, Clayton Christensen, in his jobs-to-be-done model, describes a market of people dressed in business attire who buy milkshakes at fast-food restaurants between 7:00 and 9:00 in the morning (http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/6496.html).

Now, that’s a market segment!

“But wait,” you say. “Everybody buys milkshakes!” And true, there are products that are purchased across broad age categories, and by both genders. But the question is not who buy, but why they buy.

People buy products for different reasons. For the purposes of learning how to create value, it makes more sense to group people around the reasons they buy, rather than their demographics, such as age, gender, or income.

Let’s look at an example. Imagine you are a commercial fisherman. Your livelihood depends on catching fish. If you were asked, “What sort of fish do you plan to catch?” and you answered, “All the fish in the sea,” you would surely be doomed as a commercial fisherman.

It turns out that not only are there many types of fish in the sea, but they have different forms and different ethologies. In other words, a method of fishing that works well for one species won’t necessarily work well for others.

Battle-tested entrepreneurs know how to fish, and when asked who will buy their product, they do not respond by reciting demographic characteristics, but by describing their buyers’ specific pains, passions, and needs.

And while the customer chooses the product, when building a new business you choose your ideal customer. Knowing your customers and what motivates their buying habits is every bit as essential as your product idea.

So, if the most important element of your product or business idea is the market segment you want to serve, and you think you can serve it in a way that matches your vision, then make a decision to treat your market segment as the fulcrum on which to pivot. In other words, plan your product, distribution channel, marketing tactics, and sales methods to fit the needs of your market segment.

If you are committed to solving a market segment’s problem or addressing a passion or need, you should be solution agnostic.

Famed marketer Seth Godin says:

Great customers . . . will engage and invent and spread the word. It takes vision and guts to turn someone down and focus on a different segment, on people who might be more difficult to sell at first, but will lead you where you want to go over time.1

For most innovation endeavors, your chosen market segments drive the business model.

BUSINESS MODELS

If you evaluate some basic building blocks of your proposed business model such as the types of solutions your customers require, your revenue model, your selling method, and how much customers are willing to pay (in other words, the relationship between you and your customer), it becomes clear that your market segment(s) drive(s) your business model, and not the other way around.

Conversely, a business may consciously choose to have a specific type of relationship with its customers and therefore purposefully block certain market segments from becoming customers. There’s nothing particularly wrong with this, but just do it with your eyes wide open.

Not to beat a dead fish, but knowing how you’re going to approach your market segment is a critical point in understanding your business model. Here’s what you need to ask yourself:

- Are you committed to a certain business model, and therefore to finding the market segments that fit it?

- Are you committed to addressing a specific problem or passion, and therefore willing to seek the appropriate market segments and let the remaining business-model building blocks fall where they may?

- Are you committed to serving a particular market segment, and therefore willing to find the most pressing issues and work toward a business model that can address them?

Whichever way you choose, the process of segmenting your market is one of the most poorly understood concepts in today’s business world, yet, as we can see, it is one of the most powerful.

The market segment you pursue is inextricably linked to other aspects of your business model. In addition, differences in how you reach customers within your market, their expectations of the buying process, how their trust is earned, the pricing they’ll accept, and the messaging that attracts them may represent different market subsegments.

What are the value propositions, the benefits and messaging (bait), the pricing structure and channels (tackle), and the length of the sales cycle (how likely a fish will snap at your line)? Will you need a big net (full-page ads in the Wall Street Journal) to catch many small sardines? Or will you need to staff and finance a whaling ship and be out to sea for months at a time to catch two or three whales (enterprise sales model)? Or perhaps you need to chum the waters a bit (freemium)? Maybe you’ll be hunting on a reef with a spear gun for 20-pound groupers (business-to-business [B2B] sales at a conference)?

You can build a mobile app for senior citizens, launch a Facebook campaign targeting Fortune 100 CEOs, or charge $25 for a food-cart hamburger if you’d like, but if there is a mismatch between the market segment and your product, tactics, and/or pricing, then be prepared to have to wait for that early retirement to Hawaii you’ve been planning.

As with many aspects of entrepreneurship, the practice of segmenting your market seems commonsensical but is more complicated than meets the eye. The problem is that few take the time to truly master it.

Entrepreneurs carry market segments around in the back of their minds, relying on their gut to determine whether they’re seeking the right customers. The problem is that, when you’re chasing revenue, any and all customers will seem like the right customer.

Common mistakes in segmenting:

- Dividing groups of people by “firmographics” or demographics.

- Dividing groups by arbitrary characteristics, like “influencers, “early adopters,” or Facebook users.

- Dividing by product category, such as fine-dining restaurants or electronics/smartphones.

- Dividing by vertical markets, such as health care or financial services.

KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE: WHY SEGMENTATION MATTERS

Perhaps nonintuitively, you must go big to go small. Big businesses started small, pretty much by definition. You are more likely to discover what will go big by focusing on individual “use cases” and methodically growing those to include more people. Without such focus, it’s easy to fall into the trap of trying to be all things to all people. Big companies get big by being a few things to a large market. Additionally, don’t mistake faulty market signals. You might think that a plethora of feature requests indicates a positive market signal, but these are potentially fatal without knowing who they’re coming from and why.

A southern California startup we recently spoke to was shuttered by its CEO after he had an epiphany during a meeting with a large, influential partner prospect:

I was sitting in his office and the potential partner asked the rather simple question: “What is your core value proposition?” I sat there, mulling over the features upon features we had added to the product over the prior few months based on in-depth customer interviews, automated feature requests, and conversations with prospects, and I realized I couldn’t answer the question.

I went home that day and sent an e-mail to my list of 1,500 customers telling them that regretfully, the product would no longer be available.

If you haven’t done the proper market segmentation, categorized feature requests by segment, and made the effort to understand why the customer has asked for a particular feature, then you are no closer to product–market fit than if you had received no requests at all.

This isn’t to say that you cannot eventually pursue additional market segments. The point is that it’s very difficult to pursue many at once, especially if they’re particularly divergent.

When you catch a fish you didn’t mean to catch, it is called a by-catch. This can be serendipitous—for example, if you were fishing for mackerel (a small fish) but you accidentally hooked and landed a white sea bass (a large and very delicious fish). Generally speaking, however, you do not want to hook a leopard shark when fishing for halibut. As you have no intention of eating the shark, you need to get the hook out of its mouth so you can let it swim free, before it tangles your line. Suffice it to say: Be wary of catching fish you aren’t prepared to eat.

MARKET SEGMENT

Let’s say two stakeholders—an information technology (IT) manager and the chief information officer (CIO)—face the same issue: network security. As you might imagine, they each deal with the issue from very different viewpoints. The IT manager will focus on fighting any breaches in security, while the CIO will focus on evaluating the potential risks of exposed assets. The CIO doesn’t look to IT managers in other organizations to find solutions, and an IT manager will not look to CIOs for the best products to solve the issues. In other words, they do not speak the same language. They represent different market segments.

Clues that people are in different segments:

- Their depth of pain or passion is markedly different.

- They hang out in different places—for example, Facebook versus LinkedIn.

- They expect different solutions—for example, fast food versus a sit-down meal.

- They expect different distributions—for example, online versus brick and mortar.

- They expect different sales methods—for example, field sales versus e-commerce.

Clayton Christensen asks, “What job is your product hired to do?” In his now-famous example, a researcher for a fast-food restaurant found that a large portion of milkshake purchases in the morning came from commuters:

They faced a long, boring commute and needed something to make the drive more interesting. They weren’t yet hungry but knew that they would be by 10 a.m.; they wanted to consume something now that would stave off hunger until noon. And they faced constraints: They were in a hurry, they were wearing work clothes, and they had (at most) one free hand.3

Proposed changes to the product to increase market penetration focused on maximizing its utility for a specific segment—the commuter. This illustrates another point: It’s very important that when asking what job your product performs, you don’t lose sight of the customer. The more you know about your customers, the more you know about your segments and even your subsegments. And the more you know about your subsegments, the more you know about attracting more of that particular group or, alternatively, which segments to ignore.

Market segmentation isn’t only about how to design a product for your customers, but about how to market and sell to them. As with the other phases of building your startup, you will determine your ideal market segment by interacting with your customers (customer development), testing (viability testing), and measuring (data).

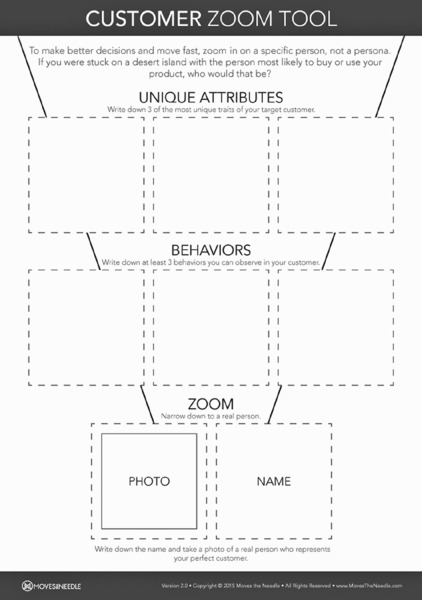

PERSONAS: CREATE A REAL CUSTOMER

Popularized by Alan Cooper in 2004, personas are a description of pretend users and what they wish to accomplish. Wish to accomplish is another way of saying “the job a consumer wants done.” The concept of personas was originally used as a tool to ensure that products were developed in ways that would resonate with users. We believe the concept is useful in helping you understand your customers, as well as how to market and sell to them. That is, rather than treating sales and marketing as problems of distribution, think of all customer engagements as aspects of the desirability problem you’re trying to solve. You do that by identifying who your customers are and understanding their goals and desires.

Cooper says that personas need not be real users, but user archetypes. In our opinion, it’s better to identify someone in the real world who fits your ideal customer profile. You want to be able to visualize your customers so clearly that you will recognize them when you see them.

In B2B environments, you create a persona for all purchase influencers, including user types and decision makers. Every market has multiple personas, and each persona might have multiple “use cases”—in other words, ways of using the product. Ideally, you design your product around one persona with the most compelling use case.

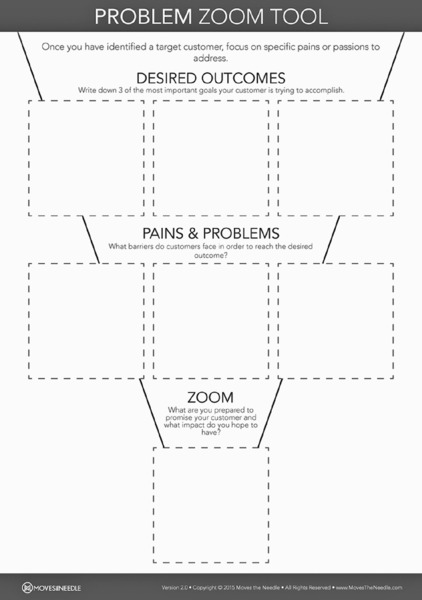

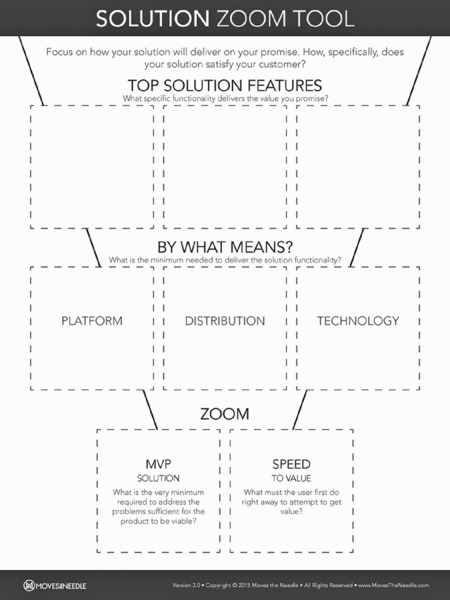

The compelling factor—that is, what drives us to buy—can be plotted along a continuum. This goes back to the idea of pain and passion. A product is considered a painkiller if it is a must-have product, as opposed to a vitamin product, which is merely nice to have. A shot of adrenalin, for example, addresses a passion.

Alan Cooper talks about a higher level of compelling—that which evokes desire. “People’s desires always have a way of emerging after their needs are satisfied. When a person needs something, she will do what is needed to get it, but when she desires something, she is loyal to it.”4

The success of your startup depends on finding a use case that evokes desire. You want to go beyond solving a problem. Over time, you will have to work at discovering what aspects of your business create that desire in your customers. It may be a combination of things, such as product support, superior customer service, usability, exceptional return on investment, and so on. In our Value Stream Discovery model, we refer to this as making your customer “passionate,” which we’ll address in a little bit.

CHOOSING A MARKET SEGMENT

As we’ve discussed, the market segments you decide to pursue will drive your business model. You can write a detailed plan and fill out your canvases on what your product platform will be, how it will be distributed, what marketing channels will be the most efficient, and how the product will be sold, but these should all center on your specific market segment.

(Unless, of course, you choose your market segment based on one of those criteria. In other words, if you choose to disrupt the distribution model and serve only customers who are willing to buy computers off the Internet, then your distribution has chosen the segment that will behave that way.)

Notice, however, that we did say “choose.” You do get to choose your market segments, after all. Not only does this affect the potential size of your business, but it may also affect how you feel about it. It’s important that your vision for the business aligns with your values and that the market segments align with your vision.

Carla’s Dream Jobs

We were helping a social entrepreneur, whom we’ll call Carla, whose vision was to help out-of-work women find their dream jobs. Carla is passionate about changing the lives of these women in fundamental and meaningful ways. She wanted to create a marketplace that would match their aspirations with real-life business opportunities.

One business model that she and her team were considering had the job opportunity side of the product provided by large businesses that would require an enterprise B2B sales model. She lamented the possibility of needing to build the product to satisfy that segment, thereby threatening her vision as well as her relationship with the segment she wanted to serve. She questioned whether she would have the same passion for her business if she had to work too long in that vertical (niche) market.

We reminded her of several things:

First, she owns her vision. Ultimately, she gets to do what she wants. The size of her business will be affected by the choices she makes.

Second, if she is to see the business through, she’ll be at it for a long time. Many entrepreneurs have a tendency to squash their own time lines. If she chose to pursue this particular strategy until it was successful, she would need to be at it for years, not months. Moving on to adjacent segments, perhaps those more closely aligned with her values, would be a long way out in the future. Deciding early whether she wished to commit to that path is important not only to herself, but to future customers, employees, and investors.

Third, you are not ready to be a startup if you can’t do the things you don’t want to do. That doesn’t mean losing your vision, but you need to be flexible in order to realize your vision.

Our discussion ultimately led Carla and her team to choose a different segment for the opportunity side of the market, one that was more in line with her vision.

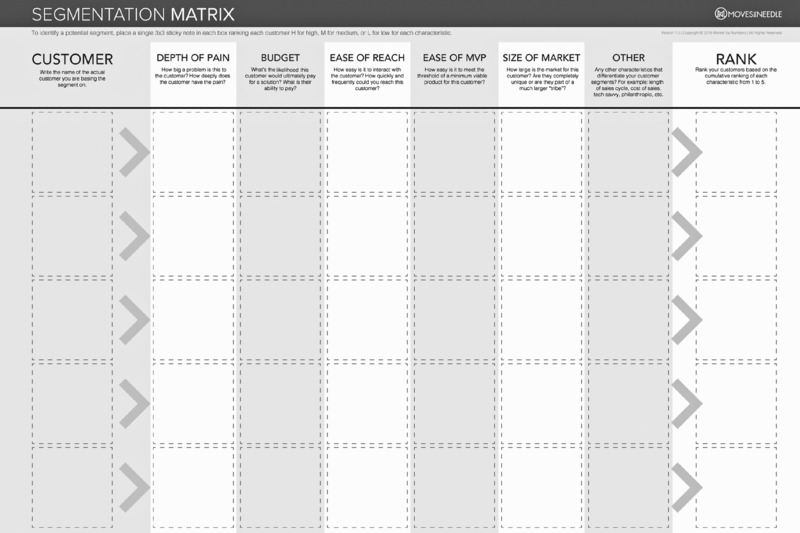

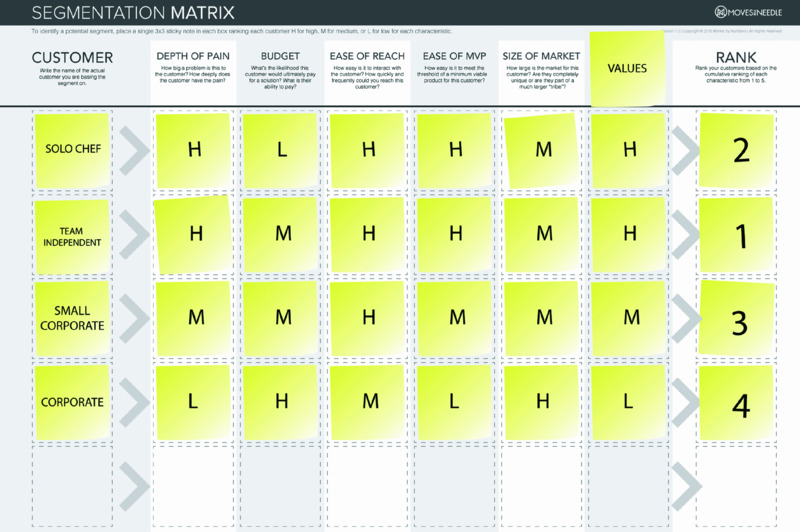

One way to help you narrow down which segments you should pursue is to create a segmentation matrix. List segments (or, better yet, personas) as row titles and criteria used to evaluate segments as column heads.

For the restaurant example, we list the different restaurant segments down the left-hand column and the criteria we use to evaluate the segments across the remaining columns. We chose the following criteria:

- Depth of pain: How serious is the problem we’re trying to solve for this particular segment?

- Budget: Can the segment pay for a solution?

- Ease of reach: Are segment customers marketable through relatively easy channels?

- Ease of minimum viable product (MVP): Do we think the solution is relatively easy, or is it complex?

- Values: How do we feel about serving this segment?

In our example, we took more of a back-of-the-napkin approach, whereby we simply ranked each criterion H for high, M for medium, or L for low, and eyeballed which segment(s) appeared to be the one most worth pursuing.

The criteria you use are up to you and your business. Be sure to choose characteristics that differentiate the segments. If all evaluations for a particular criterion are high, then that criterion is not serving a purpose for this exercise. Other criteria might be:

- Length of sales cycle: How long does it take to acquire a new customer?

- Cost of sales: Do sales require people on the street or are they online conversions?

- Tech savvy: Does the segment look for technology solutions to problems?

To be sophisticated about the approach, you can weigh each criterion. For example, if depth of pain is most important, the weight is 4 out of a range of 1 to 4, but ease of MVP may weigh only a 2. Then, you can score the criteria for each segment. Finally, you can use a mathematical formula to determine which segment scores the highest.

The score for each row (segment) is shown on the Segmentation Matrix that follows.

This exercise helps you identify the segment characteristics you need to evaluate—in other words, the values of your matrix. Are they accurate? Speak to your customers to find out.

Does the solo chef really have the highest pain? Is the solution the easiest to provide?

As you prepare to validate the assumptions captured in your personas and market-segment characteristics, prepare a list of five people or organizations you can approach for each segment.

In our first book, The Entrepreneur’s Guide to Customer Development, we detailed how to find, approach, and hold conversations with members of your potential market, but we won’t repeat that here. Suffice it to say, avenues for reaching your potential customers are all around you.

- Access your network through Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

- Use alumni organizations.

- Cold-call.

- Use the friends and family of your friends and family.

- Visit online communities.

- Visit offline meet-ups.

- Use Craigslist.

- Send out surveys.

Although we eschew catchall motivational phrases, there is credence to the clarion call “Just do it.” To be an entrepreneur, you have to be willing to do things outside your comfort zone, to do the things that you don’t feel you’re good at, and to take personal risks that make you feel vulnerable. You must.

The way to get started is by creating tasks that are manageable. Looking at the success of big businesses may inspire you, but the tactics we see them undertaking don’t necessarily represent their size. All big businesses started out small, by definition. You must start small, too! You can find your thousandth customer only after your hundredth, which came after your tenth, which came after your first.

You don’t need to draw up big strategic plans to find the first 10 customers who care about your product; you just have to go out into the big, bad world and find them.

So, what do they look like? If you don’t know, take a stab at describing one. Close your eyes and imagine them. This is the process of creating assumptions—guesses, really—that give you something to measure against when you go out into the real world. Then, go out there and find them, and talk to them.

If You Get Nothing Else from This Chapter

Like most things in life, there’s no one right way to do segmentation. You cannot understand the solution to the problem of a particular segment, however, without understanding your customer deeply. Some prefer to choose one segment at a time, go deep, and then move on to the next if the first one fails. Others prefer to go less deep across multiple segments until one becomes the leading candidate.

Still others align resources across multiple segments, for example, a 70–20–10 split where 70 percent of your resources are committed to learning deeply about one segment, 20 on a second, and 10 percent as opportunistic. Your choice may depend on resources, if nothing else.

The point isn’t to fill out tons of templates like those included under “Work to Do” at the end of this chapter. The point is to document your assumptions and begin validating (or invalidating) them.

The path toward success begins by nailing the delivery of value to a narrow, well-defined group of people who share a pain or passion, speak the same language, and would look to each other for referrals to products or services that address that pain or passion.

This group of customers can be defined as a persona. The persona may have multiple use cases, but one is more compelling than the others. The use case represents a goal the customer has, or a desire; put another way, it represents a job for which the user needs to hire a product.

Hopefully, you will encounter multiple segments, and you will likely need to focus your energy on one segment in order to nail your value proposition. In time, if successful, you will tackle other segments, too.

Documenting your segment assumptions, even if backed by market research, does not prove your assumptions; rather, it helps you think them through and establish what needs to be tested. Only the market determines the validity of your assumptions. Documenting your assumptions gives you a baseline to measure against when you get out of the building.

Enterprise tip: Enterprises often use expensive design firms to describe personas that represent their current customer base. This is fine. But understand that although this sort of traditional market research does a great job of categorizing existing customers, these personas do not work well for innovation. Why? Because more often than not, the composite pictures created out of researching existing customers don’t create a picture of real, live human beings who have pains and passions that need addressing.

To get that, you have to leave the building and create real-life personas based on understanding the complexities of real, live human beings. The good news is that when first validating products for these people, you don’t need validation that represents “statistical significance.”

Why is that? Because we’re not looking at random samples. When creating new products, whether in a startup or a large enterprise, you’re not trying to find a certain percentage of a random population of humans. You’re looking for a handful—tens, dozens, hundreds—of real people who are deeply committed to the pain or passion you’re attempting to address. You’re not worried about thousands or millions until you’re at the scaling stage. All in good time.

WORK TO DO

- Develop your personas by using the Customer, Problem, and Solution Zoom tools from Moves the Needle.

- When thinking about your customers, don’t start with “everyone who” or “anyone who.” Answer these four questions:

- What is the pain or passion? To get deep, ask yourself, “Why do they have this problem?” This should not be a shallow response.

- What impact will solving the problem or exciting the passion have on the customer? If the impact is small, you don’t have a market; you must find a deeper pain. How does your product change the customer’s life?

- Where do the customers hang out? If you wanted to find them online, where would you browse? Which forum? Which blogs? What Twitter hashtag? Where would you find them offline? What stores? What meetings? What events?

- Who influences your customers? Which blogger? What personality? A specific author or celebrity? A spouse or partner? Parents?

- Create several more personas for different use cases.

- Create an anti-segment, one comprised of personas that appear at first glance to be ideal customers but will never buy. Why won’t they buy? How does that help refine your ideal customer?

- Create a segmentation matrix. Choose the most important characteristics with which to evaluate the segments.

- Get inspired, get out of your comfort zone, and go do it.