6

THE LEAN JOURNEY

Lean Startup™ is a mindset: the elimination of waste in the discovery and creation of new value. Its application evolves with your idea. At the beginning of your innovation effort, you are very likely wrong about your assumptions, and what you believe to be true is probably false. Executing on false assumptions is the epitome of waste.

“Eliminating waste” sounds like a reasonable enough idea. Understanding customers, testing assumptiogns, and using evidence to make decisions all sound pretty straightforward. Completing the lean startup exercises in this book, documenting assumptions on sticky notes, and even conducting viability tests sound pretty easy.

Lean Startup is hard.

Once you get the mindset, you will understand how to apply your own version of lean startup to any endeavor that faces uncertainty.

The trick to success is separating what is known from what is not known. Known has been validated in the market; unknown hasn’t. When something is known, you optimize its execution. In an existing market, you may truly know how to market and sell products. You can document the process. You can teach it to others. You can manage the execution of the process.

You can’t simply execute in the unknown. Or you can, but it means you’ve got one shot to get it right. So, what are some examples of “known”?

- Has your business idea been done before?

- What’s needed to start a dry cleaning business?

- How do you make and sell toothbrushes with NFL team logos?

- What’s an effective marketing channel for upper-middle-class men between the ages of 35 and 55 who drive sports cars and live in Southern California?

You, as a new business owner, might not know the answers, but the answers are pretty readily available, because these have been done before. You can find (and perhaps pay for) good answers.

Answers to questions within the unknown don’t exist. There are approximations, analogies may be found in the market, and competition might provide clues. But if what you need to know hasn’t actually happened in the market, you’re left with guesses—educated guesses perhaps, but guesses nonetheless.

The unknown is where fear comes in. In the known you can measure your progress. You know when you’re failing or succeeding. In the unknown, you’re floating in the dark; you can’t see where you are, what’s up, or what’s down. But you can deal with the fear. To do so, you need to determine what you can control and what you cannot.

The biggest fears come from what is unknown and out of your control.

The “unknown” is defined as not having relevant evidence in the marketplace; it is otherwise indicated by your inability to predict the future. The unknown that you have no control over includes the economy, weather, “acts of God,” terrorism, and so forth. You can’t predict these things, and worrying about them while trying to build a business is pretty much a waste of energy.

You can and should, of course, take steps to mitigate the risk of the unknown and uncontrollable happening: Put some money aside, have a disaster preparedness plan, make sure you have the right insurance, and so on. Note that none of these actually reduce the risk of one of these events occurring, but they do provide some amount of protection in case they do, and this should help to reduce some of your anxiety.

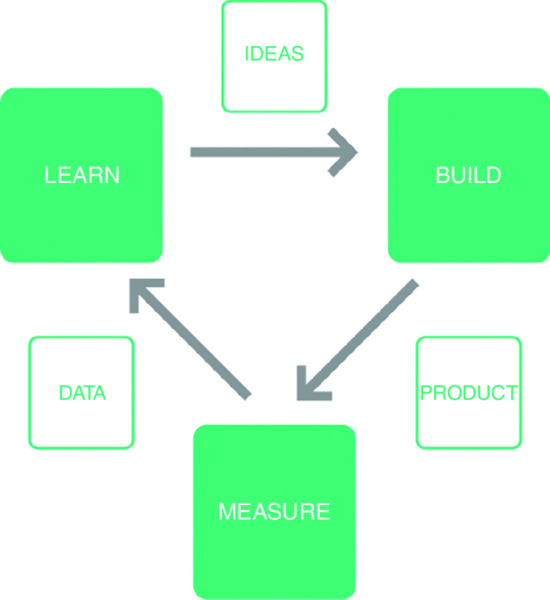

That leaves us with the “unknown” that you do have some amount of control over. Take a scientist, for example. The scientist faces uncertainty by definition. She believes some combination of chemistry will counter the effects of a disease. She doesn’t know. How does she find out? By running experiments. She has a hypothesis: “Chemical compound A will reduce effect B for disease C.” She can design an experiment to validate or invalidate the hypothesis. She runs the experiment and measures the results. Based on the test evidence, her theory is confirmed, or she needs more evidence so she designs and runs another experiment, or changes something fundamental to her theory, perhaps giving up on that chemical compound or applying it on a different disease or symptom.

Lean startup is all about treating your unknowns in the same way!

Looking again at the innovation continuum, the more your idea is a breakthrough idea, the more uncertainty you face, by definition. The earlier you are in your business also increases uncertainty. The process never stops: You start with very few knowns. You document your unknowns, and you turn your unknowns into knowns, which gets the business engine started. You continue the process until the business is moving, slowly at first, and then fast, perhaps with a bit of reckless abandon, and finally, with speed and precision.

This is Eric Ries’s build-measure-learn loop.

And then, you begin again.

With all this uncertainty, how does one know where to dive in?

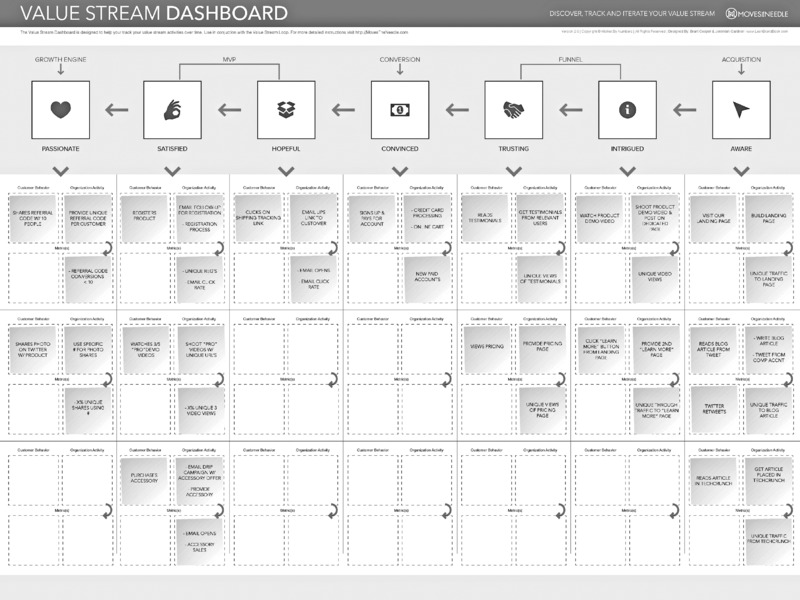

Use the Value Stream Discovery tool to direct your efforts. Whether a solo practitioner or a team, a startup or an enterprise, a new product or old, sustaining or disruptive, you can find where on the dashboard you should focus.

Apply the 3 Es of lean entrepreneurship:

- E—Empathy: Understand the customer deeply.

- E—Experiment: Test business model assumptions.

- E—Evidence: Use data + insights to direct next steps in building your company.

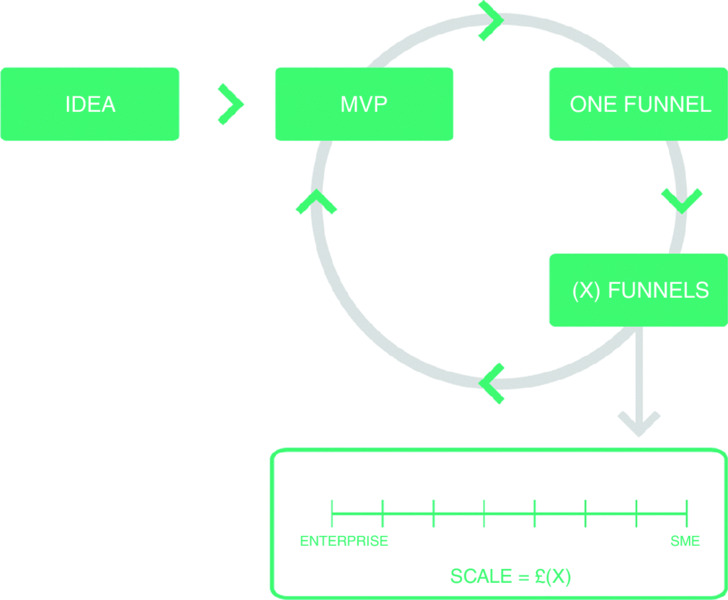

FROM HERE TO ETERNITY: GROWTH PHASES

We can look at growth as a series of phases. There’s typically a plateau at each phase, where the company struggles to balance learning and executing.

The first three phases are dominated by learning:

- Phase 1: Idea phase: This is gonna be big!

- Phase 2: MVP for a few: I’ve proven that a few people care!

- Phase 3: A funnel of many: I’ve proven that a lot of similar people care, and some are gaga!

The next two phases must balance learning how to scale, while accelerating the learning already done.

- Phase 4: Multiple funnels: Holy wow, we’re growing like crazy with a bunch of different groups of people! (Wonder if we’ll be profitable someday.)

- Phase 5: Scaling a profitable business model: Shampoo, rinse, repeat.

To continue to grow, businesses must either go through multiple loops (Phases 1 to 5) or acquire (or merge with) companies that have already learned and executed on complementary business models. Going through the loops again might entail:

- How to sell new, related products to existing market segments.

- How to sell existing but somewhat tailored products to new market segments.

Both of these might require new product learning, maybe whole new minimum viable products (MVPs), new marketing funnels, new messaging, and new positioning. The new learning must be balanced with continuing to execute on the first successful loop through the five phases, without disrupting the value created.

It’s tricky! Sometimes startups find a whole new business that requires abandoning their early adopters. Enterprises often give up on promising new ventures too early, because they compare the success of the new venture with the existing core business, often worth billions of dollars!

But more often than not, businesses convert wholly from learning to executing and then plateau. The size of the business is a function of how many loops through the five phases it experiences.

PHASE 1: IDEA PHASE: THIS IS GONNA BE BIG!

We all dream of our ideas hitting it big, but we can’t start there. You have to go small, to go big. All businesses start small. Instead of focusing on where you hope to be, start by testing your most basic assumptions.

Ideas Prime the Value Stream

Phase 1 is where you practice your first customer empathy via the methods described in Chapter 5. The early empathy work is a precursor to the Value Stream Discovery tool. You need to learn about who your customers are before you dive into their behaviors.

Getting Narrow: Empathy

Work to validate that your customers are who you think they are. Some entrepreneurs choose to brainstorm as many potential market segments as possible, and document assumptions regarding their characteristics and existing problems, prior to getting out of the building.

You could, for example, use the segment matrix to document segment characteristics at a high level, and then go seek to validate those characteristics. Essentially, you’re going shallow, but broad.

Alternatively, choose the persona you think is the most ideal, whom you imagine to be the most likely to be an early adopter. You proceed to go out into the world and attempt to validate that one segment. In other words, you go deep, but narrow.

Customer Focus: Experiment

Think of your empathy project as a series of experiments, and create hypotheses before you go out into the world. For example:

- If I interview 10 consumers at the mall, 70 percent will tell me they hate shopping at the mall.

- If I watch five customers interact with our product, 80 percent will configure the tool correctly.

The idea is to put a stake in the ground. By formulating hypotheses with specific objectives, you have established a baseline to measure against that indicates success or failure.

Early on, don’t hold yourself too accountable over the specific numbers, since you don’t truly know much yet. You’re trying to find patterns in the market, and in the beginning you’re trying to establish a feel for passing or failing.

For example, say you interviewed 10 people, and 60 percent said they hate shopping at the mall. You didn’t achieve your metric, but is 60 percent truly failure? Not really. What was common about the 60 percent? Can you discern a pattern? If you went out again, what would be the number? Go do it!

You’re not looking for statistical significance in this phase. You’re not testing a random sample, so the adored bell curve doesn’t apply. You’re looking for 10 people who share the same problem!

You’re looking for the number of people who belong to your market segments, how deeply they feel about the problem you’re describing, and how enthusiastic they are about the way you’re trying to solve it.

How you interact with your customers evolves over time and depends heavily on what you are trying to learn. At the beginning, the most important objective is to simply establish what you hope will be a long-term relationship with individuals based on your empathy for their situation.

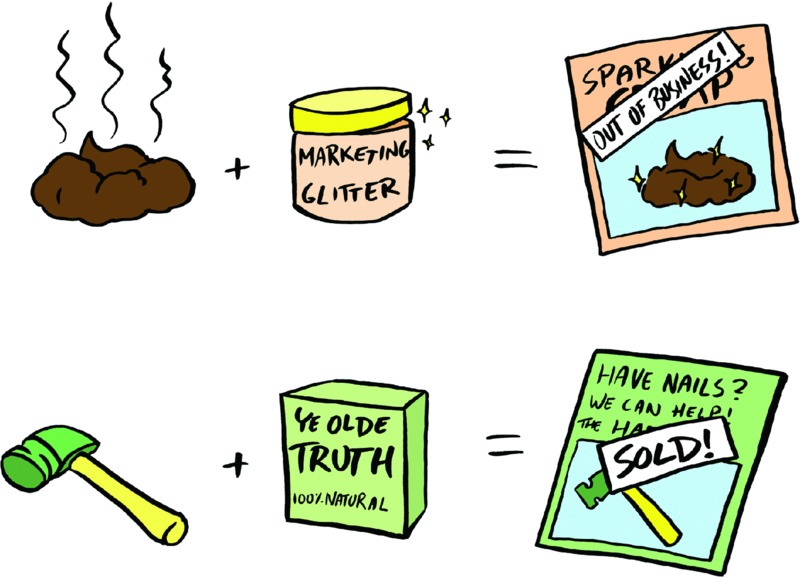

The most typical problem entrepreneurs face when first speaking to customers is that they are unable to resist talking about their solution. No matter how they originally frame the conversation, the entrepreneur inevitably starts with, “I have this great idea!” This is pretty lame. The customer feedback you get is also lame. It’s way less painful for your customers to nod and say, “Yep, that’s a swell idea!” and send you on your way than it is for them to get into an involved discussion about why your idea is lame, only to hear you say, “Eh, you just don’t get it.”

Asking your customer to give feedback puts your customer into the context of helping you, when really you are there to help them. Unless you establish the context of the customer’s problem, you can’t believe much about the feedback.

If you don’t have a deep understanding of the pain or passion of your target customer, you have no business talking about your solution. No one cares about your product. Seriously, no one cares about the features, the platform, or the architecture. The customers don’t care about what’s in your secret sauce; they just want it to taste good. They care about solving their problem, and if you are truly in the business of solving the problem, you should want to know as much as you can about it from their perspective.

It’s true that most of the great innovations of the world came about without talking to customers first, but how did they come about?

- By accident: Scientist Sir Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin when after returning from vacation he observed mold growing in petri dishes he had accidentally left out.

- By rapid experimentation: Inventor Thomas Edison tried numerous material combinations to find a commercially viable filament for the incandescent lightbulb which was actually invented 80 years before Edison.

- Timing: Underlying technology must often be in place for an idea to finally catch on. If the timing of Facebook and Friendster had been reversed, perhaps the winner would have been different.

Henry Ford didn’t famously say, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”1 The quote is used to support the notion that one shouldn’t ask customers what they want. While it’s true that one should take care in the methods of learning from customers, how one responds to the customer is at least as important as the method of interaction.

A noninnovator would think, “Well, I can’t produce a faster horse, so I’ll be done with that!”

An incremental innovator might say, “If I improve the wheels on the carriage, the whole system will move faster.”

A breakthrough innovator might realize, “If I put a steam engine on the carriage, I won’t need a horse at all and I can go twice as fast.”

The point isn’t doing what the customer says, but rather understanding why customers say what they say—and to run experiments to validate their behavior.

As part of your interaction with customers, you should start thinking about how to validate what they’re telling you. In other words, can you run experiments that test their behavior?

Understanding Deeply: Evidence

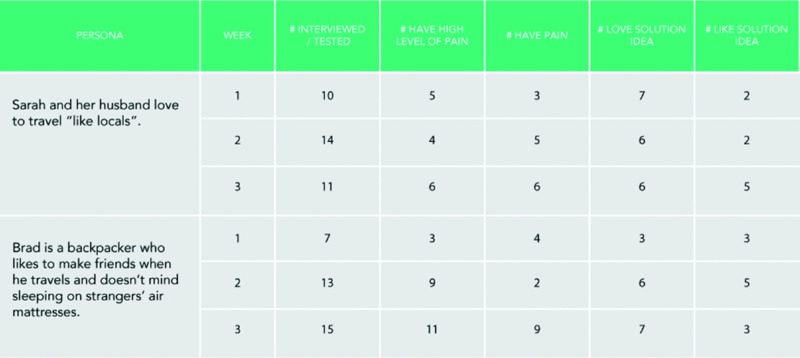

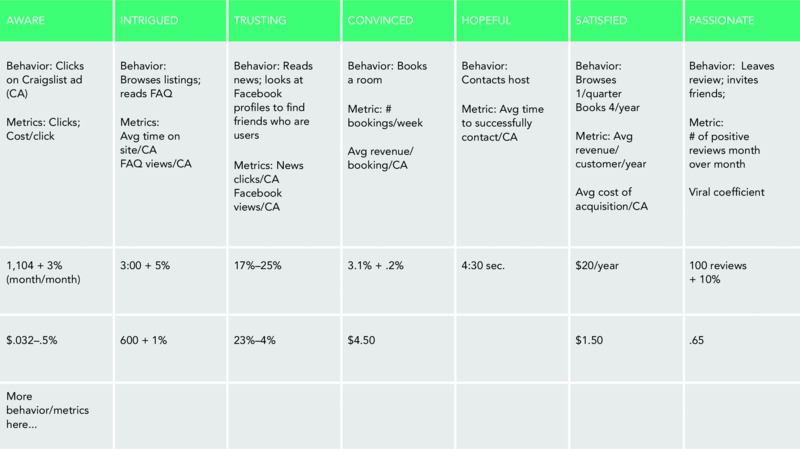

Since you’re just getting started, your data is about finding the right customers. There’s no one right way to track, but you might use a dashboard like the one shown at the bottom of this page.

Don’t forget to ask why and to document the insights!

Are You Ready for the MVP?

The end of Phase 1 comes when you have enough relationships with people chomping at the bit for your solution that you’d better start showing them something. You’ve successfully “bucketed” your potential customers by segment characteristics in the segment matrix. You feel as though you understand them deeply. They want to co-develop a solution with you.

PHASE 2: MVP FOR A FEW: I’VE PROVEN THAT A FEW PEOPLE CARE!

Phase 2 is where you start getting into your solution validation work, starting with viability experiments that lead you directly into your minimum viable product (MVP). The empathy phase has given you strong signals about the right customer to pursue, the problem you should solve, and the direction your solution might take.

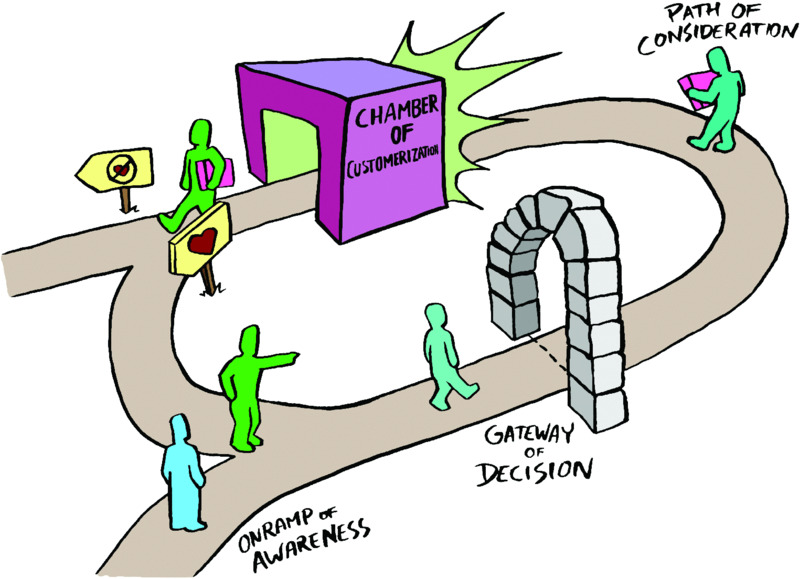

Value Stream Discovery

From the Value Stream Discovery perspective, you are ready to create assumptions across the seven states of the customer journey. Start by answering these two questions:

- What promise are you prepared to make your customers? (Intrigued state)

- What is the minimum functionality you must provide to fulfill the promise? (Satisfied state)

Then apply the 3 Es:

- Empathy: What is the reaction to the promise? Why?

- Experiment: What is the riskiest assumption about your solution?

- Evidence: What evidence do you need to generate confidence to move to start building the solution?

Phase 2 is where you hit your first wave of growth.

First Wave of Growth

The first wave of growth comes from pure hustle. You’ve nailed the value proposition with the product and learned how to market and sell by getting out in the real world and doing it.

Danger lurks in acquiring customers from multiple segments at this point, which you will likely do. It’s extremely difficult for most business models to grow while trying to serve multiple market segments, which require different product features and different marketing messages and selling techniques. Yet it’s difficult not to be opportunistic and take sales where you can when you first get going.

We once worked with a company whose CEO came to us all excited about its growth. “We’ve hired this great vice president of sales, and he’s totally kicking butt. We’ve closed half a dozen deals in the past month and things are really taking off!”

Several months later, we heard from him again: “We had to let the sales guy go. It turned out he sold 10 deals to 10 different segments. They all wanted different things. We couldn’t find any commonality. It was a nightmare!”

The thing is, that sales guy was doing what he was supposed to do, but he was the wrong salesperson for the company’s stage at that time. One tip is to distribute sales compensation over time, such that if a customer doesn’t stay, the salesperson doesn’t get fully paid for that sale.

For online products, it’s difficult not to acquire multiple segments. This is okay as long as you create buckets to store them in and monitor sales, marketing, and support costs for each one. Here are some potential differences between subsegments:

- Varying depths of pain felt will result in different engagement and different requirements to achieve passion.

- Hanging out in different places requires different marketing tactics.

- Different funnel conversion steps require different marketing and sales activities.

- Related but slightly different value propositions result in different product requirements, different messaging and positioning, and different paths to passionate.

When acquiring early adopters or early mainstream customers opportunistically, these differences may not materialize; they rear their ugly heads when you attempt to scale.

Value Stream: Are Customers Intrigued?

The Intrigued state is when your customers believe the solution you’re offering will solve a problem they have. It consists of two primary components:

- The utility promise: You will solve problem X with product Y.

- The aspiration: Solving the problem will have impact on Z.

Now, of course, marketing is a bit more clever than all that, but these are the two components that must come from the messaging and positioning. They are critical because the utility promise drives the value stream state Satisfied, and the aspiration part (one hopes) speaks to the value stream state Passionate.

You must fulfill the promise to have a viable business, so you mustn’t overpromise. You can’t promise to fulfill the aspiration.

The rent-a-room marketplace Airbnb’s early adopters were corporate travelers (attending conferences) who wanted to have a great travel experience beyond business traveling; they desired a “local experience.” The website messaging evolved over time to attract these users:

- “Stay with a local when traveling” (launch).

- “Find a place to stay” (2009).

- “Welcome home” (2015).

The old business adage “Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM” actually contains both the utility and the aspiration. It implies the promise of high uptime, while stressing the impact that may have. IBM, of course, couldn’t promise that an IT manager would never get fired.

Value Stream: Are Customers Satisfied?

Recall from Chapter 4 that your customers become intrigued when they respond in a positive way to the utility promise you’ve made to them. You are promising to solve a specific problem (or set of problems) in a specific way. Customers enter the satisfied stage when you fulfill the promise.

We know we’ve achieved a minimum viable product (MVP) when we reach the values we’ve set for the satisfied stage. We’re testing with handfuls of users at this point, not thousands or even hundreds. In large B2B industrial applications, this could be just a few customers.

Again, we’re starting out with a (now educated) hypothesis: If I provide users with specific functionality X, they will use the product in a specific way Y over some time period Z.

- Airbnb: Satisfied travelers visit and browse listings on the website on average once a month, and rent space once per quarter.

- Video sharing: Satisfied users view videos three times a week, and upload a video once a month.

- Marketing analytics software as a service (SaaS): Satisfied users look at the marketing activity dashboard every day, and create a new activity once a month.

- Contact lenses: Satisfied customers buy new cleaning fluid once a month.

- Jet engines: Satisfied customers order more within one year, buy parts and tools monthly, and extend maintenance contracts.

Just kidding. Please don’t use lean startup on jet engines. But all products must achieve the Satisfied level to be successful, and all customers behave in specific ways that indicate they’re at that state. If you’re not hitting your metric, one of three things could be wrong: The metric is wrong, the segment is wrong, or the product is wrong.

You can iterate on the product, each time hypothesizing “if we build X, customers will behave in way Z.” If you run out of ideas, then you might need to look to a different market segment. Of course, you should be communicating with your segment the entire time to determine why you’re not seeing the behavior you expected.

Finally, it’s possible that your metric is wrong. Is it possible the behavior you’re seeing is as good as it’s going to get? Is it good enough? Can you grow? Can you build the business you envision with the behavior you’re seeing?

They’re Using Our Product: Empathy

Empathy during this phase focuses on going as deeply as possible into understanding the most significant value you can add. You’re trying to figure out what is the minimum you can provide such that customers will pay currency for the value provided.

Think about the myriad features Microsoft Word now contains versus the basics of the first word processor software application!

What you are doing now is fundamentally different from requirements gathering. What must the customers have to solve a big-enough problem that they will buy (or use) your product?

Less empathetic perhaps, but part of your customer development in this phase, is to understand the messaging and positioning necessary to attract and convert your early adopters. What words make them feel like you’re speaking to them?

Designing Tests: Experiments

The empathy work you did in Phase 1 has pointed you in the right direction, and now you want to start making it feel real to your potential customers.

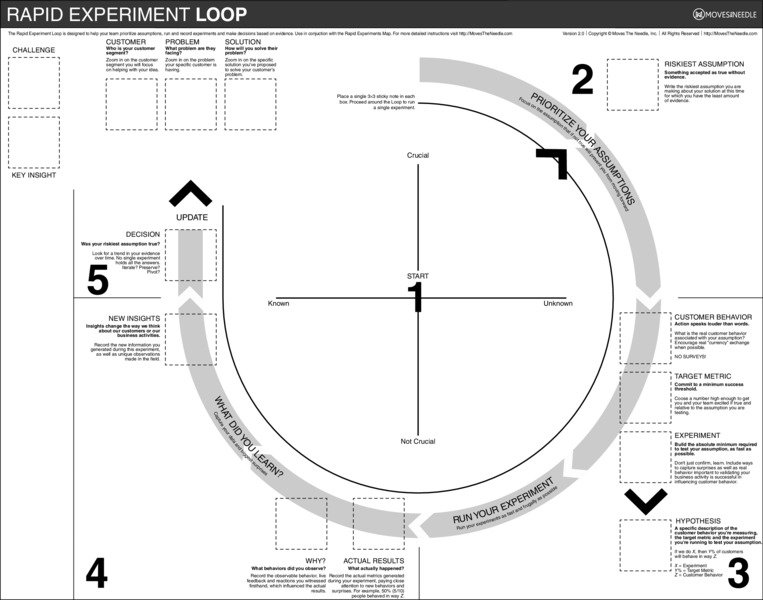

Quick recap of Move the Needle’s Rapid Experiment Loop:

- Brainstorm assumptions: What must be true for your solution to work?

- Prioritize assumptions: Which assumptions are the most critical to success and the most unknown?

- Let’s design an experiment:

- What’s your hypothesis?

- What will you build?

- What behavior do you expect?

- What is the data result you expect to see?

- Run the experiment!

- Compile the evidence.

- Make a decision on what to do next.

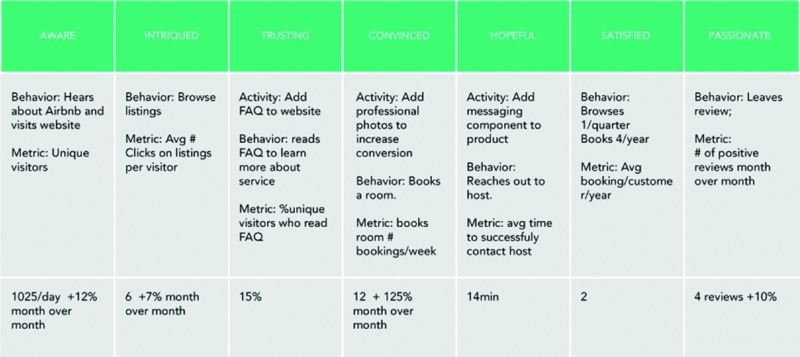

How might Airbnb have looked at this? Airbnb is an online marketplace for renting vacant rooms, houses, or apartments to travelers looking for an enhanced travel experience.

- Assumptions: Think about what has to be true from both the host’s and the traveler’s side for the marketplace to work. Write the assumptions as positive statements. If the marketplace is to succeed:

- Apartment renters and homeowners will let strangers stay in their place for the short term.

- Travelers will rent from strangers who are not property managers of the space.

- Travelers are seeking alternatives to hotel experiences.

- Photographs of an apartment plus description will suffice to convince travelers to book a room.

- Airbnb is legal.

- (There are many, many more.)

- Prioritize:

We want to find the assumptions that, if untrue, mean that some important aspect of the business idea must change for it to succeed.

The MTN loop has a 2×2 grid with the vertical axis measuring how crucial the assumption is and the horizontal axis measuring how known versus unknown the assumption is. The assumptions in the upper right are the most unknown and most crucial. These are the riskiest assumptions.

Of our list of assumptions, the two most critical and unknown are the first two.

- Apartment renters and homeowners must be willing to let strangers stay, so this is very crucial.

- Travelers are willing to rent from strangers who are not property managers is also very crucial.

There is no Airbnb business if either of these is not true. There’s more evidence in the market of the former than the latter, so we’ll say the second is our “leap of faith” assumption—in other words, the most risky.

- Experiment: Next we want to test the behavior of travelers to determine whether they’d be willing to rent from strangers.

- Our hypothesis is: If we put up a simple website with pictures and a description of apartment space, we will be able to rent it to out-of-town travelers.

- What we must do: Create a simple page on Wordpress.com that includes the Airbnb description; include pictures of air mattresses; provide phone number or e-mail address to book room; market to conference attendees.

- Behavior we expect: All mattresses will be rented out.

- Success metric: One out of three mattresses is rented.

- Execute the experiment: Build the site; get the word out to conference attendees.

- Compile the evidence: Three out of three mattresses are rented. Why? All hotels were booked, and travelers needed a place to stay.

Insights? The travelers appreciated the breakfast and tips on where to visit in San Francisco as if they were locals. The apartment was clean; the hosts were friendly.

- Decision? Persevere. Push on to the next-riskiest assumption.

The process includes going back and updating existing assumptions, creating new ones, and reprioritizing on the Rapid Experiment Loop.

(This is a fictional account of what Airbnb founders could have done with the experiment framework, based on what they actually did. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Airbnb.)

One loop completed! It’s certainly possible to complete this example in less than 24 hours. At entrepreneur Trevor Owen’s Lean Startup Machine workshops, teams regularly run multiple experiments over a weekend, validating and invalidating assumptions, proving and disproving ideas.

“Fail fast, so you don’t fail big.” Each experiment might fail the first time through, but the time, energy, and resources wasted pale in comparison to the traditional way of building the entire product before experiencing big failure.

The process can be repeated over and over again throughout the business model, testing product ideas, features, marketing, distribution, sales, and so on. Multiple teams—if you have them—can focus on different parts of the Value Stream Discovery tool, each employing the 3 Es.

Typically, early experiments don’t deliver a tremendous amount of value. Airbnb went straight to a concierge–landing page hybrid viability test. In other words, the founders didn’t merely do a one-page website to test interest; they actually fulfilled the promise, as well.

Early experiments often take smaller steps that prove potential customers will behave in ways you expect them to:

- Consumers will allow their bodies to be scanned if it results in finding better-fitting clothes.

- Businesses will let you have sensitive data if the analysis you provide through your algorithms will give them insights on consumers.

- Employees will eat healthy snacks, even if found in a gift bag labeled “naughty snacks.”

- Senior corporate executives will play hopscotch outside a conference room to display the need for a “fun break” at work.

- Restaurant patrons will choose damp antibacterial napkins rather than dry paper napkins after eating.

We’ve seen all these experiments run. The results, in themselves, don’t determine whether a project moves forward, but the results plus insights from asking participants “why?” indicate where changes in the idea need to be made.

When you feel that you have generated enough evidence that your Value Stream Discovery hypotheses for Satisfied and Intrigued are solid, it’s time to build the actual minimum viable product.

Your Minimum Viable Product

If you have made the effort to interact with potential customers and have run viability experiments testing customer behavior, your first (true) minimum viable product (MVP) is your first effort to deliver validated value to a known customer.

In this context, an MVP is not a landing page or a mockup of your application. It’s not a 3D model or nonfunctioning prototype. Your minimum viable product has the least amount of functionality necessary to solve a problem sufficiently such that your customer will engage with your product and pay for it (if that’s your revenue model).

Your experiments now have such a high degree of fidelity that they more closely resemble the final product than a viability experiment.

In the Value Stream Discovery tool, your MVP creates satisfaction for your customer because it fulfills the promise made in the intrigued state.

It will take more than one try. You’re not going to nail it the first time. In fact, you’re never really done. In today’s value-creation economy, there’s no such thing as done, which is why you might as well get your product into the hands of a few customers as soon as possible. You won’t learn what you’re missing or getting wrong until you let someone try to use it. Hence the minimum in MVP.

Your product may or may not require an artful user experience, 42 features, beautiful packaging, a kickstand, and blue buttons to be viable to your chosen market segment. A viable product, at the very least, delivers just enough of its value proposition that customers will use it. The trick is admitting you don’t know all that’s required to be viable.

Releasing early to early adopters (not to the entire market) is the most efficient way to learn what’s missing. Too much product hides the specific functionality that provides the value. The core functionality that provides value, such that customers are satisfied because the product fulfills its promise, likely informs how you will go after future market segments. It tells you what cannot be destroyed in future versions.

Your MVP doesn’t guarantee high growth or even success, but you can’t achieve those without it.

Most startup endeavors fail in the MVP phase. Iteration through features can quickly result in flailing, to the point where founders can no longer recall their vision or the original value proposition. Alternatively, perhaps the value proposition was vague from the outset!

Reid Hoffman, founder of LinkedIn, famously said, “If you are not embarrassed by the first version of your product, you’ve launched too late.” This idea causes massive cognitive dissonance in the startup world, because entrepreneurs are scared that:

- Customers will leave behind a buggy, unfinished product and never return.

- Their idea will be stolen.

Unfinished Product

Investor Paul Graham says to launch “when there is at least some set of users who would be excited to hear about it, because they can now do something they couldn’t do before.”2 You don’t truly know when your users will be excited until you try to excite them. Launch doesn’t mean release it to the world and make hay about it. It means get it in front of early users to understand whether you have uncovered the quantum of utility or you are at least on the right path.

Entrepreneurs often swing from one extreme to another. If they focus on minimal they forget viable, and if they focus on viable they don’t know when to stop building.3

If you have a controlled early release that turns out not to be viable, it’s easier to retool compared to building until you think it’s done without truly knowing what “done” means.

This is the gist of iteration. You take a reasonable stab, otherwise known as a hypothesis, also known as an educated guess, with success metrics attached. It’s not exactly right. Some customers seem to be kicking the tires but in a rather lackluster fashion. Make changes and try again. If, instead, you keep building features, delaying your release—and then the product isn’t exactly right—not only did you lose time finding that out, but it’s harder to know what you got right and what you didn’t!

You want to understand what product functionality produces your must-have use case—the specific way people interact with your product that delivers value—as this provides the foundation of your product moving forward. The must-have use case is the one you must not destroy as you continue to build out the product and bring on additional market segments.

Once you are able to provide the utility that excites the user, you will find that the early adopters are willing to put up with glitches. This is the classic definition of the early adopter. As thought leaders in their space, or as social leaders that others look to for new products, they tend to forgive product issues as long as the core benefit addresses their pain or passion.

The great irony to the idea that customers will never return to a faulty product is that the entrepreneurs who espouse this philosophy stake their entire business on their personal belief that their fully fleshed-out product isn’t somehow faulty. But there’s always one more bug to fix, one more design element to clean up, one more feature to add. You know this because you don’t fire your engineers and designers after release. You need them to fix bugs, clean up faults, and add features.

But I thought you said the product is done!

Startups don’t have a brand to kill. Just because you paid $20,000 for the logo, that doesn’t mean you have brand. The success of your product in fulfilling its promise is the foundation of your brand. Viability is a threshold, not a continuum: The winner is the first to be viable, not the one with the most (or even the best) features.

Stolen Product

The idea that people troll the Internet to steal ideas is amusing. It’s characteristic of either overbelieving in your idea or not having enough of an idea. Consider this:

- After releasing a product, the hardest thing to do is to get people to care. Contrast that with the fear that trolls will not only find your product, but also launch a company to compete with it!

- Have you heard of any stories in which an idea was stolen because it was released too early?

- Face the truth: There are very few truly new ideas. It’s highly likely someone is already considering, if not building (or has built), a version of your idea.

- You’re going to launch someday anyway, right? All the time you’re not releasing, you’re not getting early customers. Customers are what create the business!

It’s actually hard to take someone else’s idea and make it one’s own.

Learn and Decide: Evidence

At this stage, your evidence might include a little bit of data about how you acquire users and make them Intrigued, but primarily you’re trying to learn what makes them Satisfied.

In Phase 2, Airbnb’s evidence on the bookings side of its marketplace might have looked like the chart shown at the bottom of this page.

Learn and Decide Evidence

| AWARE | INTRIGUED | TRUSTING | CONVINCED | HOPEFUL | SATISFIED | PASSIONATE |

Behavior: Friends tell friends and visit website. Metric: Unique visitors |

Behavior: Browses listings Metric: # clicks on listings per visitor |

n/a | Behavior: Books a room Metric: # bookings/ week |

n/a | Behavior: Browses 1/quarter Books 4/year Metric: Average # bookings per customer/year |

n/a |

| 100/day +2% week over week | 3/day +5% week over week | — | 2/day +.5% week over week | — | 2/day

|

—

|

PHASE 3: A FUNNEL OF MANY: I’VE PROVEN THAT A LOT OF SIMILAR PEOPLE CARE, AND SOME ARE GAGA!

Phase 3 is where you have customers. Congratulations!

Value Stream Discovery

You should return to your Value Stream Discovery tool and update your assumptions with what you’ve actually learned. You have a bunch of “knowns” now. You’re no longer completely wandering in the wilderness of unknowns.

In Phase 3, where you’re expanding your MVP into the larger market, you’re working on multiple areas of your business model at the same time:

- You’re searching for that magic something that produces Passionate customers.

- You continue to work on the MVP to shore up the Satisfied level and to get customers there quicker by working on Hopeful customers.

- You’re learning how to sell, especially getting people Convinced to buy, on a growing but still small scale.

- You’re learning, but not yet optimizing, the marketing represented by Aware, Intrigued, and Trusting.

The objective is to apply the 3 Es to expand your market reach within the chosen segment, by learning:

- What is the impact you hope to have and that the customer hopes to achieve through your relationship? (Intrigued state)

- What makes your customer believe you’re the right business to fulfill your promise? (Trusting state)

- What moves the customer over the final hurdle of purchase? (Convinced state)

- What must your customer do with the product to first try to achieve its value as quickly as possible? (Hopeful state)

- What is the minimum functionality you must provide to fulfill the promise? (Satisfied state)

- What about the business or product drives an emotional connection and creates loyalty or passion? (Passionate state)

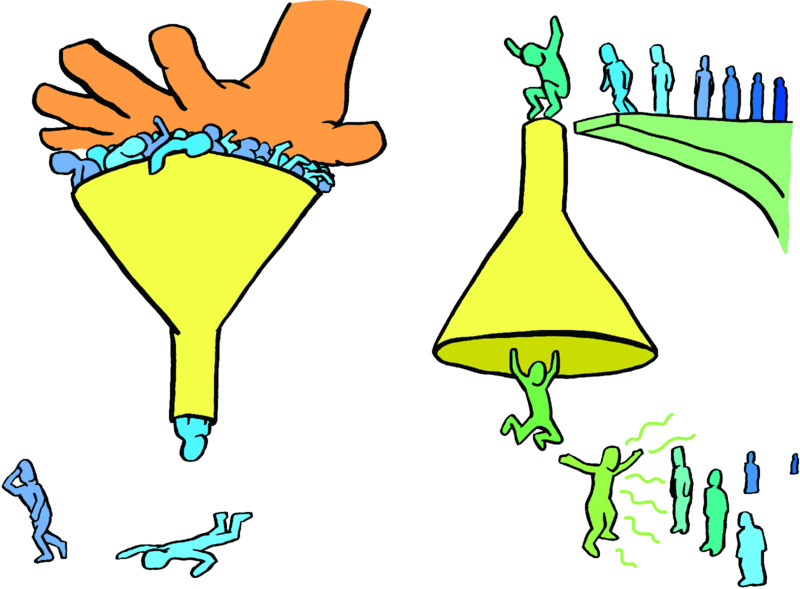

By the end of Phase 2, you should have a handful of Satisfied customers. The objective of Phase 3 is to get more of the same. There are two primary ways of doing that:

- Turn Satisfied customers into Passionate ones so that they act as your advocates. They put new customers into the top of your Aware funnel without your spending a lot of money on marketing activities.

- Learn from your existing customers how to acquire and convert more of the same.

Second Wave of Growth

Your second wave of growth comes from narrowing your focus to that of your high-value market segment and nailing it. Recall our segmentation matrix.

You should have enough evidence now to know which market segment is the one you should concentrate on.

In the B2B world, not surprisingly, the larger the business you’re selling to, the more complex the product needs to be, and the more complex the selling process. The bigger the fish you capture, the more you want to concentrate on dominating that one segment before moving on to the next.

As businesses transition toward Internet-based products, marketing, and selling, you can adopt multiple segments faster. You still face the same multiple-segment issues discussed earlier, but on a smaller scale. It doesn’t hurt as much to acquire adjacent segments, but you want to focus resources on the primary ones.

Value Stream: Passionate

Business leaders often wonder why, although their products sell well, the businesses fail to gain momentum; they don’t understand why customers leave—why they cannot capture customer loyalty. Achieving passion is a tricky thing and not entirely predictable.

Here are a few ways to help you think about the Passionate state:

Passionate comes from the aspirational aspect of the Intrigued state. Customers desire not only the utility promise (i.e., you will solve problem X), but what the impact on the customer will be for solving that problem. What will it mean for their lives or how they feel about themselves? It’s not that the business can promise achievement of the aspiration; rather, it’s the journey the customer and business go on together to achieve it. It’s the intersection between customer aspiration and the reason the founder was driven to start the specific business.

- A manager becomes a hero at work and gets a big bonus because of the amount of money saved upon purchasing your product.

- A mom feels like a better mother.

- A husband feels like a better spouse.

- A small business owner becomes a better entrepreneur and can now afford to take his family to Italy every summer.

- A child grows to love music.

Passion may come from the love of the product. This is certainly the case with many people and their Apple iPhones (us included!). Steve Jobs had an innate sense of empathy for people who love simple, high-functioning products with an elegant design and a delightful user experience.

Passion may come from an emotional connection to a company that perhaps isn’t connected to the product.

- A “green” customer feels loyalty for helping to reduce carbon emissions, because a company has decided to do so.

- A philanthropist customer feels loyalty for helping feed the undernourished, because a company has committed to do so.

Passion is driven via human interaction, business to customer:

- The online shoe store Zappos drives passion from amazing customer service.

- A consultative salesperson can create passion for solving complex problems.

Passion comes from extraordinary performance beyond expectation.

- The CEO attributes part of a significant market share gain to working with a specific vendor.

- The business unit general manager was able to beat all profit forecasts through a dramatic decrease in costs by applying a new technology.

Other aspects of the business model that might drive passion include:

- An online classified ads marketplace that brokers pick up and deliver to dangerous locations allows the underprivileged and underserved to participate in new markets.

- A content-marketing platform like HubSpot offers free content marketing to small business owners to help them be better business entrepreneurs.

- Different packaging for household cleaning products creates passion in Method Products’ customers.

Measuring Passionate behavior is tricky. Other than the survey methods we mentioned, Net Promoter Score and Must Have Score, you might start with behavior. What do Passionate people do? They tell their friends or colleagues about you or invite them to your networking platform. They show off their relationship with you by brandishing your logo. They act as a reference or are willing to go public with a case study.

Often, the best way to measure the behavior is to induce it through specific business activities. Back in the 1970s, Breck shampoo actively encouraged viral word-of-mouth activity by its customers.4 The commercial said: “. . . and then you’ll tell two friends, and they’ll tell two friends, and so on, and so on,” as the screen doubled the number of customer portraits repeating the same words, and doubled again and again. This is viral marketing, since the growth is exponential.

It’s funny how Internet marketers “discovered” viral marketing!

Network-effects businesses must have viral growth to succeed. Like the social networking giants Facebook and Twitter, many network-effects businesses have products—theoretically, anyway—in which the value of the product increases the more the network of users grows. To measure virality, you measure the number of invitations a customer sends out and the number of those invitations that result in new Satisfied customers. This is called the viral coefficient and must be greater than 1.0 for network-effects businesses that depend on scale to succeed. For every person who signs up and uses the product, more than one additional friend or family member will also sign up and use the product.

If your business model does not depend on scaling to millions of active users (in order to monetize that scale, typically via advertising), your word-of-mouth coefficient does not have to be greater than 1.0. It’s still a great way to measure passion, however, since merely Satisfied users don’t share products.

To induce and measure word-of-mouth marketing for products that are not network-effects businesses, you can do a few things:

- Run a campaign that encourages users to invite other users. This can be a temporary friends-get-in-free offer or a long-term agreement like getting one month free for every new paying customer you bring on board.

- Use social media tools like Facebook along with coupon codes to track conversions.

-

Build a method into your product for users to invite friends or colleagues, and track that as you would the viral coefficient.

For offline products, bring your Passionate customers online where you can measure their behavior.

- Run a social media campaign, during which your customers post a picture with your product in action.

Otherwise, ask customers to give testimonials, provide a quote in a press release, or help publish a case study. These are tough to get and will come only from Passionate customers. And, like all good Passionate behaviors, put new customers into the top of the marketing funnel; in other words, make new customers Aware.

Value Stream: Convinced

In the Value Stream Discovery framework, customers who need convincing have already determined that the product looks like the right solution and the company is trustworthy. But to convince customers, you need to do something more. To convince customers to buy, you must demonstrate that the price is less than the value they will receive plus the cost of change. This sounds simple until you understand that the cost of change is as much an emotional factor as a pure money calculation.

There is a risk to change because the change might result in failure (and job loss for whoever is responsible). There is a fear of change, since one is moving from the known to the unknown. There’s an old saying from the early days of computers: “Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.” It meant that not buying from a stable, world-class company like IBM was risky, so if you chose the more expensive IBM, no one would question the decision.

To convince customers, you must overcome their final sales objections and give them something along the way that ultimately puts the equation in your favor. To do so, you need to understand deeply not only the benefits of your utility promise, but also their monetary value. Additionally, what is the value of the potential impact?

How much time will the product save? What’s the value of the time? If you now have more time and can become more proactive than reactive, what is the value of that?

What fears remain with the buyer? What is she putting at stake? You might hear comments like:

- Lack of foresight: “We don’t need a mobile solution.”

- Concern: “Your price is higher than everyone else’s.”

- Hidden agenda: “My boss doesn’t think you’re a good fit.”

- Perception issue: “The cloud isn’t secure.”

- Unclear about interest: “This is not a priority for us this year.”

What can you offer to balance the risk? For various business models, think:

- Money-back guarantee.

- Free day of professional services.

- Free shipping back.

- Buy one, get one free.

- Live demo; proof of concept; trial period.

In order to learn to overcome objections, one must interact in person with the potential customers in the first few months of selling, at least. Often startup entrepreneurs are encouraged to outsource their sales or automate through online marketing. Even if you have an online product, however, it’s important to sell your product personally in the beginning.

We once helped an Australian entrepreneur who was selling an SaaS product to restaurants. To close a deal, he had to go through the restaurant manager. It was pretty clear that he would have to call the restaurants, if not meet in person. But due to pressure from his investors, who insisted that telephone sales and field sales weren’t scalable, he was trying to automate Facebook campaigns. The likelihood, however, of a restaurant manager responding to a vendor’s Facebook ad was extremely low.

At this early stage, you’re not trying to automate your scaling mechanisms; you’re trying to learn how to scale. As you learn, if your customers will buy online, you can start running experiments online.

A/B testing or split testing describes a method of running two versions of a single conversion web page, splitting Internet traffic between the two, and measuring the results. You want to keep the number of variables low (in other words, keep differences between the pages minimal), in order to discern what is responsible for the results.

Variables you might subject to split testing:

- Pricing

- Utility promise

- Aspiration messaging

- Design

- Convinced offers or messaging

Be sure that, whether online or offline, your testing is hypothesis-driven. If you do X, customers will behave in way Y. For the Convinced state, the measurement is straightforward: If I do X to overcome the objection, customer conversion will increase by 10 percent.

Growing into a Bigger Market: Empathy

You’ve proven viability with the product you have in the market, but can you capture an entire market segment? It’s common for the enthusiasm of early wins to give way to confusion and frustration as you add customers. Often, instead of a clear picture emerging of who your ideal customer is and the features the customer needs, you opportunistically capture multiple market segments, who have different requirements.

The good thing is that by now you are regularly interacting with people who understand the problem you’re solving, so you’re learning on a daily basis. You also might be fortunate and stumble upon a bigger market segment than the one you first targeted. The key to navigating these times is to bucket your users; in other words, group them based on how they interact with your company: acquisition channel, sales and marketing funnel, and interaction with product.

To bucket your users, you need a way of tracking who your customers are, what product functionality they use, how often they use it, and how much money they spend. You’re seeking patterns in your customer data to help you determine who your high-value customer is. It’s this high-value customer that is going to lead your company into the next phase. Each one of these buckets will have a slightly different Value Stream Discovery profile.

Your customer development work focuses on understanding—from the buyers’ perspective—how they want to (or must) buy. It’s especially complicated in the B2B world, where you must become an expert at navigating the influencers, decision makers, champions, obstructers, and even the actual purchasing process perhaps driven by its own department.

You must have the right sales group for this to work. They must be consultative. They must be willing to learn first, and then meticulously document the process such that less sophisticated salespeople can replicate the process.

Until then, this isn’t about the sales process; it’s about the buyer’s process.

Startups often seek to automate this on the Internet before they’re ready. Enterprise startups want to toss this part of the business model over to existing sales teams. Both are mistakes!

Winning goes to the hustler, and that means getting out of the office and doing the learning required to establish a repeatable process.

MVP Evolution: Experiments

It’s easy to fall into a trap of believing that you can “feature” your way to success—in other words, if you simply build enough features, you’re eventually going to get it right. Truthfully, this is rarely the case. Your customers want the simplest tool possible to solve their most important problem. Features that complicate that process or are not intended for them confuse the situation. Additional features can actually destroy the value you previously created for them.

Agile programming methodologies typically include a use case for each set of functionality to be added. The use case describes the interaction the customer will have with the product and (hopefully) has been validated with the customer prior to development. Ultimately, the functionality should have a corresponding hypothesis that describes the intended behavior. If we build X, customer segment Y will use the new features two times each week. This should be included as part of the Satisfied hypotheses on the Value Stream Discovery tool.

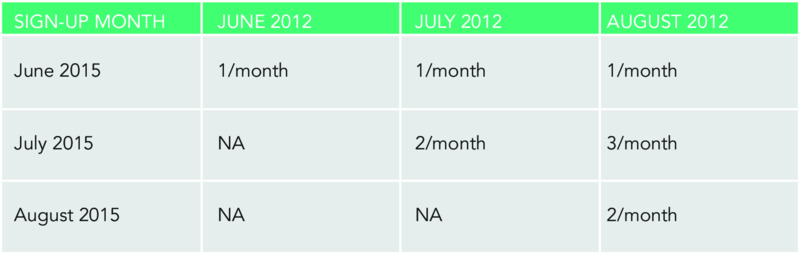

Since you already have customers, you need to measure the effectiveness of your MVP evolution. To do so, you want to measure customer behavior by cohorts. What this means is that you are grouping customers based on a shared characteristic—for example, the month they became a customer—and comparing each group’s activity relative to other groups who signed up before.

In this video-sharing website example, customers are grouped by the month they signed up and how often they post a video to the site.

Comparing cohorts allows one to see how each month relative to sign-up is evolving.

Assuming you make changes to your product every month, you’re able to track the impact of your changes on how customers are using your product. Between June and July, product changes resulted in an increase in posting videos in the first month a customer signed up. These customers continued to become more engaged in month 2. However, changes between July and August resulted in a drop in first-month engagement back to June levels.

The data don’t tell you what happened, but if correlated to product changes, the data provide a good clue. Talking to your customers will likely give you the why. Track your Passionate metrics in the same way.

Nailing a Segment: Evidence

PHASE 4: MULTIPLE FUNNELS: HOLY WOW, WE’RE GROWING LIKE CRAZY WITH A BUNCH OF DIFFERENT GROUPS OF PEOPLE!

Entrepreneur-turned-investor Marc Andreessen coined the term product–market fit to describe the point in a product life cycle when “the market pulls the product out of the startup.” What he means is that there’s a (seemingly) sudden jump in customer demand, market buzz, and sales that demonstrates that the startup has met the needs or desires of a large market.

Note that product–market fit isn’t a hypothesis; it’s a state of being: The startup is off and running.

A characteristic of product–market fit is organic growth; in other words, growth comes from word of mouth versus spending lots of money acquiring new users. Spending lots of money acquiring new users is adding fuel to the fire, of course, but the fire is already burning.

From a Value Stream Discovery perspective, you have found what makes your customers Passionate, and you understand how to move customers through the Intrigued, Trusting, and Convinced states. You are ready to apply the 3 Es to Aware.

Third Wave of Growth

The third wave of growth is about buzz. Buzz happens when you dominate a market segment or are doing well in several subsegments. At this stage, your customers are so Passionate that you can’t keep a lid on their enthusiasm. This is true product–market fit.

Product–market fit isn’t what one has discovered through customer interviews or viability tests. Product–market fit comes from the market validating your product. It occurs after iterating through market segment definitions, product functionality, and even messaging and positioning. When all three values line up as with a slot machine and you close the word-of-mouth loop, you can declare that you have found product–market fit.

The trick for the third wave is that as you reach for the mainstream market, your marketing must appeal to multiple market segments. This allows you to drive larger, more expensive marketing campaigns that bring more people into your fold.

This is where traditional marketing comes to the fore. Radio, TV, print ads, and press relations can bring hundreds of thousands of new visitors to your doorstep. The messaging and positioning are broad enough to allude to the core value proposition for broader, more traditionally drawn market segments.

There’s no magic bullet for making customers aware of you on a large scale. Starting small allows you to more easily track your cost of customer acquisition (CA) relative to purchase, lifetime value of the customer (how much the customer will spend over the duration of being a customer), and velocity (time it takes to cover acquisition cost).

The relationship your customers make with you depends on how they are made aware and marketed to.

- Existing subscribers don’t want to continue to be marketed to; they want a respectful relationship. How can you improve upon the value you are creating for them? How can you create new value? How do you reward their loyalty?

- Repeat-transaction customers often appreciate reminders, like upgrades, accessories, deals, and such. They want special treatment to bring them around again. High-cost single-transaction customers expect service follow-up, and they also may appreciate relevant up-selling, maintenance contracts, and premier support options.

- Network-effects relationships respond to ways to increase their status among peers, points systems, badges, and other gamification features.

Fundamentally, growth takes money. Early startup endeavors typically use lower-cost customer-acquisition methods because those whom they need to make Aware are more targeted and fewer in number. Eventually, you want to go after a broader appeal and massive numbers, which costs more money.

The trajectory of awareness marketing might look like the following:

- Search engine optimization, including content creation via blog, social media, video, e-books, and so forth.

- Search engine marketing, including Google AdWords, Facebook, and the like.

- Affiliate marketing, blogger outreach, product bundling, and influencer outreach.

- Online advertising targeting Internet properties specific to where your market segments hang out.

- Traditional media, including trade magazines, radio, market analysts, public relations (PR), and television.

Growth primarily comes from one of three courses:

- Selling existing products to more and more market segments.

- Developing new related products and selling them to existing markets.

- Acquisition or merger.

These all have risk associated with them, of course, but not as much uncertainty as breakthrough innovation has. Even with these strategies, companies typically stall again as a small or medium-sized business, since, truth be told, they’re operating in an established market with lots of competition. It’s also important to understand what growth levers drive your business model. In other words, what business model data must you track to establish whether you’re scaling in a way that will (eventually) be profitable? (Scalable startups often sacrifice present-day profitability to help fund rapid growth. But the data should show the ability to be profitable.)

Growth likely also comes from merger and acquisition in this phase. Buying competitors is a common way to acquire new market segments.

Value Stream: Aware

Awareness happens when a customer first learns that your product exists. It’s easy to rely on best marketing practices when reaching out to new customers, since marketing awareness has been going on since the beginning of time. From running an ad on the online classifieds website Craigslist to broadcasting one during the Super Bowl, there’s a gazillion ways to make customers Aware.

What could possibly be unknown about making customers Aware?

Yes, our world is inundated with awareness campaigns, which makes getting through to customers especially difficult. How will they come to understand you are there for them? Why should they care about your product? How will you cut through the noise?

Growth hacking is a term coined by entrepreneur and online marketing guru Sean Ellis to describe practices that combine marketing tactics and online technical skills that focus on rapidly scaling the number of customers. Like lean startup, growth hacking combines creativity and rigor; use inspiration to come up with new ideas to reach customers, but test them before deploying them widely.

For inspiration, think about these three questions:

- Where do your customers hang out? Where would you find a cluster of them either online or offline?

- Offline: Think specific industry trade shows, networking events from Meetup, the local mall, a farmer’s market, a San Francisco Giants baseball game.

-

Online: A BMW enthusiast forum, the comments section of a popular mommy blogger, a particular LinkedIn group.

These are the places you need to go to learn more about how to reach and acquire more customers.

- What is the customer doing when experiencing the pain? What is the context when they’re thinking, “If only I could” or “If only I had”?

- “If only I had a more automated way to install new computer servers in the cloud (on the Internet) that had all my software tools complied and ready to go,” says a programmer using the PHP development language.

- “If only I could have a local experience,” says a traveler when stuck in a tourist trap.

- “If only I could hire a reasonably priced floor tile professional whom I could trust right now,” says a do-it-yourself (DIY) homeowner who has just cracked another expensive ceramic tile.

- “If only I could have visibility into the capacity of my parts supply manufacturers,” says a supply chain director upon learning that mission-critical parts will arrive late.

- “If only I had a way of tracking my teenager’s time on his smartphone,” says the parent of a troubled teenager.

- “If only I had a way of getting my kids to practice their music lessons more,” says the music-loving parent who has just chided her kids for not practicing.

- What are customers doing when they become Aware of you? Imagine scenarios that are in context with or proximate to the awareness of the pain or passion.

- A developer is reading posts on Hacker News related to programming with the PHP software development language.

- A traveler is looking for vacation rentals on Craigslist.

- A homeowner is using online “yellow pages” to browse floor tile installation professionals.

- A supply chain director searches Google for “supply chain visibility.”

- A parent searches on the Berkeley Parents Network website for “keeping tabs on my teenager’s phone use.”

-

A music-loving mom is watching a YouTube video of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.

You won’t necessarily be able to reach these customers in the moment they experience the pain or passion, but if you can, that’s the ultimate hack in growth hacking. If you’re not able to, the next best thing is being front and present when they look for a solution and you are able to reinforce the correct context. This demonstrates empathy.

Next step is to experiment to see what works. Start with a hypothesis:

- Posting a link to my beta invitation landing page on Hacker News will result in 1,000 visits and 100 sign-ups.

- Posting advertisements for vacation rentals on Craigslist that drive traffic to my website will result in 1,000 visits and three rooms being booked.

- Posting ads for my home improvement iPhone app on a yellow pages website will result in 1,000 app downloads, 75 listing browsers, and five jobs bought.

If you don’t receive 1,000 visits, was there something wrong with your post? If you didn’t receive 100 sign-ups, was your messaging on the landing page wrong? Did you post the ad to the wrong site? Did your app differ in functionality from what was promised in your messaging? There are a number of variables in play, so if you’re not successful, then you iterate until you see success. If successful, you ramp up the activity until you see diminishing returns while testing other campaigns.

Value Stream: Trusting

Intrigued and Trusting represent the meat of your marketing or sales funnel. It’s a long bridge or a short jump between a customer first becoming Aware and the customer buying. It’s required that you work to ensure that customers feel as if you’re talking to them and addressing their needs. It’s vital you also imbue trust, that you instill in the customer the belief that yours is the right company to do business with.

The more disruptive your startup endeavor, the less you know about your marketing and sales funnels, despite what you think. Just as with product development, a lean startup must learn how to market and sell.

Entrepreneurs conflate both sides of a transaction: how the buyer desires to buy and how the seller desires to sell. What results is likely a horrible mismatch. The business executes a process it is familiar with, rather than the one that the buyer implicitly demands for a particular product. Buyers will not engage with a sales process that doesn’t fit with what feels right to them. You can have an incredible product capable of delivering real value that never sees the light of day, because of the wrong sales and marketing practices.5

The Internet has changed the buying equation: Buyers are more informed and empowered than ever before. Customers have more options. Thinking of marketing and sales, then, as straightforward activities that need to be executed captures an old-school mentality that must be recalibrated in the lean startup.

The selling process is composed of all of the activities necessary to provide buyers what they need or desire in order to move them through their buying process. Activities might include building a landing page, crafting messaging, creating a brochure, attending a trade show, making a phone call, and so forth, depending on your product and segment. There is an infinite number of potential activities, which is why it’s absurd to think that you already know what the best activities are for your particular product and your particular customer profile.

For Trusting, you must consider both requirements and influencers.

- Requirements might include being a Better Business Bureau member or having an e-commerce site security badge. For businesses, it might require obtaining validation by a standards body, like ISO certification. These are things customers check off, whether consciously or not, that indicate you’re the real deal.

- Say a person tells your customers to buy and they immediately go and buy. Who is that person? A celebrity? An influential blogger? A colleague?

Measuring Intrigued and Trusting is based on actions your customers take when they’ve reached that state. For selling to consumers on the Internet, this can be measured by defining multiple paths through your website that you expect your customers to take and measuring their actual paths, correlated to the Aware tactic that landed them on your site.

Home page → Case study download → Phone call → Demo → Purchase

Landing page → Video → FAQ → Sign-up → Trial → Subscribe

The customer behavior, whether online, offline, or a combination of the two, determines what the business must put into place.

Sales are more complex than they seem. For business-to-consumer (B2C) sales, you might consider:

- Who has the pain or passion?

- Who decides on the purchase?

- Whom are they trying to impress?

- Who influences the decision maker?

- What are adjacent pains or passions?

- Do they currently buy/hire products that address the need to some degree?

- What makes them feel secure?

- What makes them feel sexy?

- What do they think is cool?

- What do they dream about?

- What keeps them up at night?

- What characteristics do they share with others who have the need?

- Where do they hang out offline and online?

- How do they become trustful when purchasing?

- How do they decide a product is a good fit?

Most business-to-business (B2B) sales include multiple people and multiple influencers; the buyer is different from the user, and the buying process includes whole departments unrelated to either user or economic buyer (person with budget). You have to consider:

- Who is the buyer versus the decision maker versus the financial approver?

- Where does the budget for the purchase come from?

- Who else influences the decision?

- What compliance regulations come into play?

- What is the purchasing process?

- Is a pilot or proof of concept required?

- What is the length of the purchase process?

- Are there specific channel requirements?

- Who is the internal champion?

- Who might be motivated to obstruct the deal?

On top of all these, there are different answers for different market segments. To beat a dead horse, this is why we must learn and test before executing. You can spend a lot of time and money using so-called best practices that don’t work.

New Markets: Empathy

After you’ve automated the repeatable processes as much as possible in your first segment, you should begin again. Use what you’ve learned, but go back to Phase 1 and take the time to learn what new segments you should be tackling. Some are likely to be obvious; bigger opportunities might be silently lurking.

Startups and enterprises often think that simply scaling the way they grew the first market segment is all they need to do. This often results in a big, flat plateau in growth. As stated earlier, new market segments often need new marketing messages, new product features, and even new distribution channels.

Sometimes you can take existing messaging and expand it such that it attracts a broader audience. This is really where taking a new look at your branding artifacts might help (logo, website URL, taglines, etc.).

Go back and update the segmentation matrix, and see which segment makes sense.

Your MVP Isn’t Minimal Anymore: Experiments

Once you’ve learned what it takes to deliver your value proposition, there’s no longer a need be minimal. You’ve validated the value you are creating and for whom, and now it’s time to expand your product.

We’ve heard startups dramatically declare, “We’re not doing lean startup. We have lots of momentum, and our users will leave us if we do an MVP.”

Exactly!

Or rather, exactly, you should not be minimally viable after achieving product–market fit. Build out the product, but continue to test and release quickly:

- Build within the demands of your high-value market segment.

- Build to experiment with adjacent segments.

- Build to block competition, if necessary.

- Build to create passion.

The danger is building new functionality that destroys existing value. This is where measuring satisfaction and passion in cohorts is critical. In the event of decreasing customer engagement, for example, you should be able to determine whether it correlates with new product functionality, or even market positioning.

Product–Market Fit: Evidence

| Business Model | Transaction | Business Drivers |

| E-commerce/Internet transaction | one time | average revenue per order; frequency of customer purchase; cost of customer acquisition |

| SaaS subscription | monthly | monthly recurring revenue; churn rate; lifetime value of customer; cost of customer acquisition |

| Enterprise software/hardware | one time + % recurring | average length of sales cycle; average revenue per order; monthly recurring revenue; average up-sell/cross-sell per year; cost of customer acquisition |

| Manufacturing | periodic | average revenue per order; frequency of customer purchase; cost of customer acquisition |

| Consumer (free) | User sign-up + monetization at scale | average revenue per daily active user; cost of customer acquisition |

| Consumer (free) | User sign-up + micropayments | average revenue per daily active user; frequency of purchase; cost of customer acquisition |

| Freemium | free to monthly upgrade | conversion rate to paid; monthly recurring revenue; cost of acquisition per paid account level |

| Mobile | one time, periodic, or free | average revenue per daily active user; cost of customer acquisition |

| Retail | one time | average revenue per order; frequency of purchase; cost of customer acquisition |

Understanding the right data for your business model allows you to track growth rates over time, as well as provide early indications of trouble ahead.

Your Value Stream Discovery tool can act as a dashboard. (See the fictional Airbnb example at the bottom of the page.)

PHASE 5: SCALING A PROFITABLE BUSINESS MODEL: SHAMPOO, RINSE, REPEAT

Simplistically speaking, growing a startup is removing an endless series of bottlenecks. You have huge, seemingly insurmountable obstacles, like no one cares about your product when you first get going and no one knows about your product even when you actually first prove the value of your MVP.

And, of course, you face too many smaller bottlenecks to mention, including optimizing the conversion portion of your funnel, or building trust. You conquer one bottleneck and see a 0.1 percent increase in conversions, and then remove another and see a 25 percent jump. You eliminate bottlenecks for one market segment, and then must begin again with the next one, with that added complexity of not breaking the first.

Phase 5 is a major transition point for vision and values. For some it’s the Valley of Death, where growth fizzles and retracts, and the startup starts a slide toward irrelevance and death. Founders are left wondering what went wrong. Had they misread the market? Grown too fast? Did they fail to pivot when they should have? Did they pivot when they should have persevered?

Other founders (or even investors) come to the conclusion that the market size is simply not big enough to justify continuing on. Assets and talent are sold off in an attempt to return investment dollars. Still others switch from being a scalable startup to being a lifestyle business—in other words, one where revenues are sufficient to pay people well, but there’s no massive growth potential, no big payout via going public on a stock exchange or by acquisition.

At this point, regardless of the number of employees or the extent of revenues, companies that have plateaued look more like large enterprises than startups:

- They’re organized in departments, by job function.

- Performance is measured by job description.

- Interdepartmental communication is managed by rules (written or unwritten).

- There is no straight line connecting job function with departmental and organizational objectives (except for sales).

- The number of job titles with normal interaction with customers declines.

- The company is optimized for execution (such as it is) and not learning.

All is not lost! Founders are often still involved with the company, and they simply must channel their inner entrepreneur. They must go back to Phase 1. Who does what? The founder does the following:

- Delegates running existing businesses to others, and begins the process of discovering new value to be created.

- Gives employees 10 percent free time to develop new ideas.

- Starts an internal accelerator or incubator, where dedicated or part-time teams work on validating new ideas.

- Teaches everyone entrepreneurial skills and empowers them to experiment as ideas emerge.

FINALLY, ENTERPRISE: LARGE AND SUCCESSFUL; SLOW AND BUREAUCRATIC

As we previously discussed, large enterprises achieved their size and status through optimizing the execution of known processes in known markets. They also grew massive from acquiring more of the same. Historically, their biggest obstacle for innovation was a lack of need. They were big and powerful, and dominated their markets.

They enjoyed economies of scale; in other words, costs per unit of product produced declined as output increased. There were (and still are) distinct competitive advantages to being big. From the 1950s to the 1990s, by the way, they also owned massive computer power that no startups or even midmarket firms had access to.

These advantages continue to deteriorate. As the power of the consumer grows, a startup can produce products for a niche market at a lower price than large enterprises can. In classic “innovator’s dilemma” fashion, large, established enterprises are forced by new market entries to retreat into smaller, higher-end, higher-margin markets.

The company structure that defines the plateaued small or midmarket businesses is more siloed and more entrenched. The problems the structure causes are greatly expanded. And to make matters worse, the company is no longer owned by the founder, but by shareholders.

There’s no hint of entrepreneurial spirit. Instead, entrepreneurialism is like a virus, facing antibodies that are there to protect the core assets of the large enterprise. It makes sense. It’s rational. In order to get big, organizations naturally grow protections.

- The legal department wishes to patent everything in order to fend off lawsuits and protect what is “invented here.”

- Compliance battens down the hatches on any activity that regulators might deem against regulations.

- Salespeople want to sell only proven, high-margin products.

- Marketing must protect the brand, the image customers have of the company.

- Finance will spend money only on initiatives where a clear return on investment is visible.

- HR hires people with the primary ability to execute.

On top of this, of course, in publicly traded companies is the need to protect the interests of shareholders, a fact that is widely misinterpreted as necessitating “maximizing shareholder value.” Though this isn’t the case, the quarterly routine of reporting financial results to Wall Street incentivizes a company to essentially maximize profits every quarter!

How is a CEO going to invest in innovations that might take five years to come to fruition? Why would business unit general managers, responsible for the profit and loss of their divisions, spend money on innovative projects that may never show a return?

In addition to arming employees with entrepreneurial skills and implementing organizational ability to learn, large enterprises must tackle the organizational antibodies. Namely, they must:

- Tell Wall Street they are investing in innovation. This is completely in line with their fiduciary responsibilities, which must include long-term company viability. This deceptively simple act will allow companies to realign compensation plans toward innovative activities.