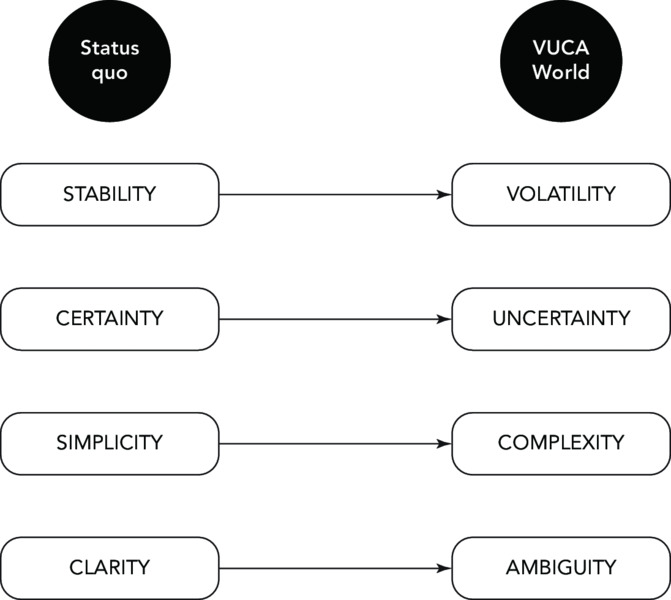

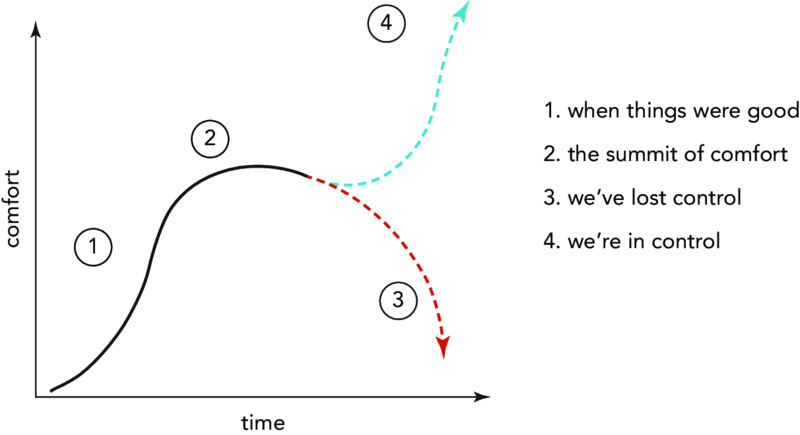

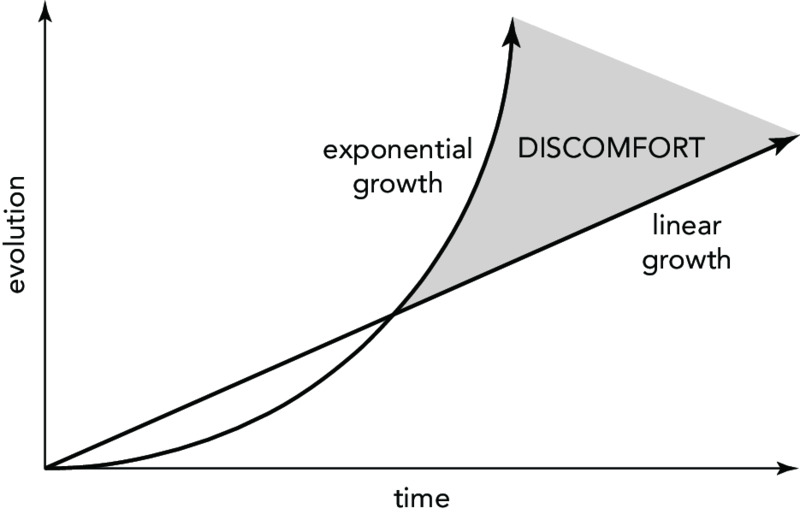

In 2008 cable television network HBO ran a series that has achieved a cult status among fans of quality television miniseries. Called Generation Kill, it was the (very lightly) fictionalised story of the US Marine Corps' First Reconnaissance Division and its role in the second Iraqi invasion of 2003 (or, as it was known, ‘Operation Iraqi Freedom'). Generation Kill was based on the book and series of articles by Rolling Stone journalist Evan Wright, who embedded with First Recon for their entire campaign, from first footfall in mid March to entry into Baghdad in early April. Reconnaissance marines are among the elite warriors of the US military. They are trained, much like alpine-style mountaineers, to move light and fast and to adapt quickly to their changing surroundings. What they don't do is move in large numbers, and definitely not in slow, methodical, predictable formations. That changed with Operation Iraqi Freedom. First Recon was sent in-country in lightly armoured open-top Humvees, with no air cover, in broad daylight, across swathes of open desert, en masse. It was not First Recon's preferred way of doing things. For an organisation such as the US military (which had so clearly identified the VUCA threat in the first place) to work in such a manner shows just how difficult we find it to let go of the old comfortable ways of doing things and embrace the volatility of the new world order. But what exactly is comfort? For most of us, comfort in life comes from: Does this sound boring? Then you are very much out of the ordinary. Think about it a little more. Politicians often talk about stability when seeking election to government; we vote an unstable or volatile government out of office. The daily weather forecast reassures us about certainty in weather patterns; it allows us to plan and prepare. There are no nasty surprises. Why do scientific and business reports start with abstracts or executive summaries? Because we like complex ideas to be streamlined, broken down, simplified. Why do you use a map? Because we always like clarity in relation to where we are. (Who enjoys being lost?) If we gave stability, certainty, simplicity and clarity an acronym, it would be SCSC, but it's not very catchy; besides, we don't need a new name for it, because it already has one: it's called the status quo, and the human race is fiercely protective of it. Be that as it may, the status quo is on the way out. For good. As you can see in figure 3.1, it's in direct opposition to the VUCA world. Figure 3.1: status quo vs. VUCA There is an economic theory known as the Jevons Paradox that can be applied to the old world order versus new ways of doing things in business. The Jevons Paradox is named for William Stanley Jevons, who in 1865 asserted that energy-efficient steam engines had caused an efficiency dilemma by inadvertently accelerating Britain's consumption of coal. In other words, the newly invented steam engine (a form of technological progress) had increased the efficiency with which a resource — coal — was being used, but an unanticipated consequence of this was that the rate of consumption of that resource had risen because of an increasing demand for train services. It's a double-edged sword, and we can also call it by another name: the Comfort Paradox. The Comfort Paradox is a problem, and it's a problem entirely of our own making. Figure 3.2 illustrates it. Figure 3.2: the Comfort Paradox Why? Because it's in our DNA to improve our lot in life, and to increase our level of comfort. Think of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. Maslow's model states there are five progressive stages that a human is motivated to reach. The most basic stage is having our biological and physiological needs met: food, water, shelter and sleep, through to security and safety — until we reach the top of the hierarchy and self-actualisation. Humanity's relentless drive towards technical innovation and sophistication is all about enabling the ease with which we secure each of our five needs. We use technology as our primary means to move through the stages. The irony is that in our efforts to make ourselves more comfortable and stable — to reach the top of the hierarchy — we are actually making ourselves less comfortable. That's the Comfort Paradox. If you don't agree, that's understandable. There are, after all, many examples of how our standards of living have improved significantly due to technological advancement. For example, current predictions have cancer eradicated by the year 2025. Some are even suggesting the Baby Boomer generation will be the last generation of people to die, period, such are the predicted radical improvements in health care and preservation of life. Notwithstanding all of this, technological innovation also brings undeniable negatives. Every day we see examples of where the use of technology designed to improve our standard of living paradoxically undermines our comfort and our ability to meet Maslow's five needs: Most of this comes from technology unavailable just a decade ago. Long-term change for good brings short-term pain. As the interplay between people, places and technology continues, and the growth rate in the development of technology, particularly computing power, continues to grow exponentially, it is in the space between linearity and exponentiality that our human discomfort occurs, as shown in figure 3.3. Figure 3.3: exponential discomfort Part of the problem with the VUCA world is that exponential growth is a concept humans find very hard to understand. Someone who does understand the concept pretty well is inventor, futurist, author and director of engineering at Google, Ray Kurzweil (whom Forbes magazine describes as ‘the ultimate thinking machine'— that's a pretty cool moniker). Kurzweil uses an analogy of firstly taking 30 linear steps (where the distance of each step is the same as the last), and then taking 30 exponential steps (where the distance of each step is double that of the previous). The distance travelled by taking 30 linear steps is approximately 20 to 30 metres (depending on the length of your legs). This might get you from one end of your house to the other, or across a busy city street. However, taking 30 exponential steps gets you around the world 25 times (a distance of about a million kilometres) or to the moon and back again. Hard to believe, right? As the growth of technology increases exponentially, it will do so at a rate we cannot imagine. And therein lies the problem. We just can't comprehend it. Our inability to keep up with the current rate of change, let alone be able to imagine what the future might look like, causes us to feel anxious and overwhelmed. It's like sitting down and trying to contemplate the dimensions of the universe: the brain becomes quickly overloaded. As we have identified, rapid change, the type that is the norm in the VUCA world, isn't something we can easily comprehend. When faced with its impact, it's not surprising that we don't understand it. We react with: Think of something that has happened to you that was so unexpected, so utterly incomprehensible, that even now you look back and think, ‘How could that have happened?' For some people this might be the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in New York and on the Pentagon in Washington, DC on 9/11. Even now, many years on from that infamous day, it is hard for most people who witnessed the events, whether first hand or as they were broadcast live around the world, to forget their feelings. Feelings that were for the most part disbelief and horror. How could such a thing be happening? The cause of this disbelief is known in psychology as cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance occurs when the brain struggles to interpret new information that does not correlate with or confirm the existing knowledge or beliefs that the brain already possesses. On that day in New York in 2001, and indeed all around the world, cognitive dissonance was occurring en masse. In a more subtle kind of way, due to the interconnectedness of people, places and technology, cognitive dissonance is once again happening en masse. In fact, it is de rigueur for the VUCA world. As everything changes at an ever-increasing speed, the frequency of occasions where the brain receives information that does not correlate with existing knowledge will increase continually. Cognitive dissonance is the root cause of people's discomfort in the VUCA world. Operating in tandem with cognitive dissonance is the concept of psychic entropy, first introduced by psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi (surname pronounced ‘six-cent-mi-hal-yi'). According to Csíkszentmihályi, entropy occurs whenever information from the surrounding environment disrupts our consciousness by threatening its goals. This in turn leads to a disorganisation of the self, impaired effectiveness and, ultimately, an internal self so weakened it cannot invest attention or pursue its goals. This idea is based on the premise that every piece of information our brains receive is evaluated for its impact on our psyche: the information is run through a filter to determine whether it supports or threatens our goals, and whether or not it is congruent with our beliefs. A self (or psyche) that becomes so weakened that it cannot invest attention or pursue its goals is not going to do well in a VUCA world. Let's go back to 9/11. Like many others, in the days that followed, I didn't feel like doing much at all. I was due to travel to New Zealand a few months later to undertake a mountaineering training course but at the time I remember thinking ‘What's the point?' And I know I wasn't the only one thinking that. For example, the Association of Surfing Professionals cancelled all but one of the remaining men's world title events for the year after the attacks. Entropy only serves to intensify and compound the seeming disorder of VUCA. The compounding of the external VUCA world with the internal dissonance of the human mind ultimately creates an internal malaise. In the old world order, when the status quo reigned, our minds were able to make sense of the outside world, and it was for the most part consistent with our expectations. In other words, cognitive dissonance and entropy were relatively infrequent occurrences. When they did occur, they occurred so infrequently and with such limited magnitude that they could be handled. In the VUCA world, it is common to experience entropy, because much of the information we receive threatens our goals and reduces our opportunity for comfort. And when our opportunities for comfort are under threat, we become incredibly anxious and uneasy. We are less likely to retain self control in this state and are more likely to react to our circumstances. Simply put, VUCA is not the ideal operating environment for people. In the immediate hours after 9/11, and after grasping the enormity of the situation, many retreated from the horror of the world. They disengaged. In times of unexpected events, when cognitive dissonance and entropy run rife, we have a tendency to withdraw from the world at large and revert to our closest and most important social groups, normally our immediate family and friends. The Kübler-Ross model is a framework that proposes five emotional stages through which a person passes when grieving. The stages are denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. In those hours and days after 9/11, I suspect most were either in denial or anger. Could it be that we now are grieving our loss of the old world, the loss of our comfort? If so, at which point of the grief cycle do we currently sit? Cognitive dissonance and entropy are not the only causes of disengagement. There is another cause and symptom of the VUCA world — that of information overload — that also leads to disengagement. There is currently much talk about the need to invest in big data. Big data is a broad term for data sets so large or complex that traditional data processing applications are inadequate. In 2014 IBM estimated that every day we create 2.5 billion gigabytes of data, meaning that more than 90 per cent of data in existence today was created in the last two years alone. As an example, Google's self-driving car gathers 750 megabytes (nearly one gigabyte) of sensory data per second. That means that in your average daily commute of 30 minutes to work, the Google car will be capturing 1350 gigabytes of data! If we apply this to the world of business, the information overload is so overwhelming that we cannot process what is going on with our usual status quo approach, because it is simply not adequate. So — we switch off. We just don't bother to understand the data anymore. And this is a problem. Because in the VUCA world, that big data is coming in thick and fast. And it's getting more complex at an exponential rate. So we now know how a VUCA world affects our mindset. If our mindset doesn't change, what kind of a future are we looking at? In her book The Shift: The Future of Work is Already Here, London Business School Professor Lynda Gratton presents two variants of the future of work. Similar to the movie Sliding Doors, Gratton has two scenarios: the Default Future and the Crafted Future. For the Default Future Gratton tells the story of Jill, living in London and working for a large global organisation. Overwhelm, discomfort and reactivity is her norm. Her frantic and fragmented life in 2025 shows that a combination of people, places and technology has created a constantly ‘on', 24/7 world, leaving her repeatedly bombarded by requests for her time, with little space to concentrate, observe, think and play. Gratton also tells the story of Briana, a member of the working poor in the American Midwest, whose life is shaped by repeated economic bubbles and crashes, and the ongoing replacement of non- and semi-skilled work by technology and the better educated workforces of India and China. The Default Future is one of isolation, fragmentation, exclusion and narcissism, where no-one works together. People are chronically overwhelmed; world events and technological change outpace the required actions and remedies. Essentially, this default scenario is a future where people have not been able to adapt or cope, and can't possibly excel. In other words, they haven't been able to adapt to the VUCA world. They have attempted to manage it by fighting the elements of the perfect storm — people, places, and technology — but they are fighting a losing battle. In mountaineering terms, they have been blown off the mountain. It is the Comfort Paradox writ large. In the second scenario, which she refers to as the Crafted Future, Gratton tells of Miguel, who lives in Rio de Janeiro. His working day in 2025 is a stimulating mix of real space and virtual engagement with a geographically distributed but interdependent team of planning specialists working on a submission to help reduce traffic congestion in a northern city in India. His work is interesting and meaningful. We also hear the story of Xui Li, who lives in Zhengzhou, China. Xui Li is an independent micro-entrepreneur who sells her hand-crafted dresses across the world via an online sales and distribution cooperative with a vast international reach. Collaboration plays a key role in the Crafted Future, where choice and wisdom contribute to a balanced way of working. This future comprises of good decisions, rapid adoption of good ideas and people taking advantage of technologies and working together in light and fast teams; it is an environment where work can truly be of value and appreciated. This is the future where all have adapted to the VUCA world and embraced the opportunities presented by the combination of people, places and technology, rather than becoming anxious and overwhelmed by the discomfort it brings. Xui Li and Miguel have been climbing the mountain alpine style, light and fast. They have embraced the perfect storm and are using it to their advantage. Idyllic predictions of a futuristic tech-enabled utopia are often criticised for being far-fetched and naive, and to an extent, this is understandable. But as the saying goes, with great power comes great responsibility, and the same thing applies to technology. What Gratton is saying is this: we do have a choice as to how we use it. It's a choice between sitting back, throwing our hands up in the air and giving up, or proactively taking action and making sure that the Default Future is not our own. We have the option to craft our future. So the challenge ahead of us is this: how we can achieve a Crafted Future in our lives and our organisations? First we need to gain a better understanding of our organisations, and appreciate that they are the primary structures upon which our society depends — why are they the way they are, and will they help us achieve a Crafted Future? The next chapter will do just that.CHAPTER 3

The old worldThe opposite of VUCA

The Comfort Paradox

The problems with exponentiality

The three symptoms of VUCA

Dissonance

Entropy

Disengagement

A crafted future?