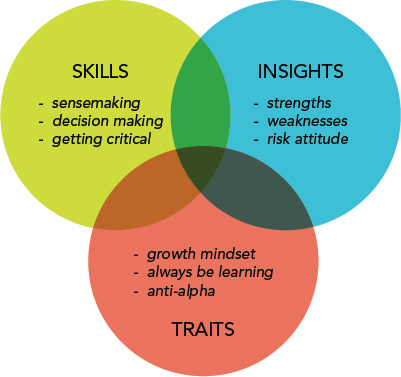

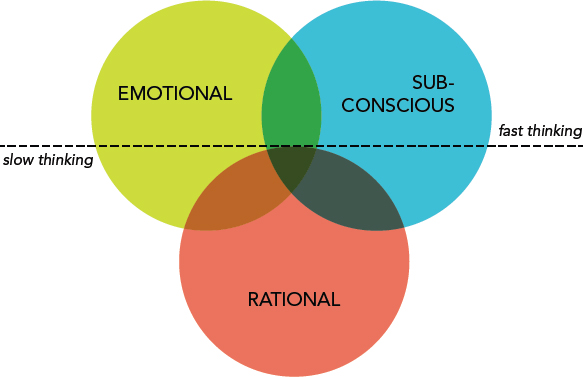

While the aim of climbing a mountain in alpine style is to move light and fast with minimal equipment, there is some very specialist gear the alpinist relies upon to make it off the mountain alive. From lightweight technical ice tools made from futuristic compounds through to mountaineering boots containing Kevlar and thermo-reflective aluminium, alpinists' lives depend on their equipment. Today anyone can jump online and kit themselves out with the latest gear. Just like the expedition-style organisation parading in alpinists clothing, though, simply looking the part is not enough. In order to bridge the gap and transition our organisations beyond the unaware, reactive and dependent stages, and to move from an expedition- to alpine-style approach, there are three skills we need to learn, three insights that we need to have about ourselves, and three character traits that we need to possess. These are illustrated in figure 9.1. It's only once we have mastered all nine of these components that we will be able to reach independence and interdependence and create an alpine-style organisation. Figure 9.1: the Alpine Style Model These nine components need to be embraced at all levels: the individual, the team and the organisation. They are what the alpine-style organisation lives and breathes. So let's get into it. The first of these three skills is known as sensemaking. Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard once said that the problem with life is that it is most clearly understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards. So how do we live forwards when the world around us doesn't meet our expectations? The answer is very straightforward. We must learn to sensemake. Sensemaking is the process where we develop plausible hypotheses of the unknown, test the hypotheses and then either keep them (if they are correct) or discard them (if they are not). Academic Karl Weick developed the concept in his book Sensemaking in Organizations, although smart mountaineers have been doing it since they first started climbing mountains more than 100 years ago, and alpinists have taken it to a new level. In its simplest form, sensemaking is how we structure the unknown into something that is more known (in the VUCA world, it is difficult, if not impossible, to know something completely). Most importantly, it's a tool we employ before we start to act. Thus, sensemaking is an absolutely essential tool to have in the VUCA world. Sensemaking is the process of devising a plausible understanding — let's say, for example, a map — of the changing environment, and then showing this map to other team members and testing its assumptions for validity, before further refining it, changing it or throwing it out, ready to start again with a new understanding and a new map. Note the description of the map as being plausible, rather than accurate. In the old world, we had time to acquire the information needed to draw an accurate map, and the signals that we needed to pay attention to were clear. But in an uncertain and exponential world, we won't have enough time to collect all the information that is out there. Not only that, but in the new world, with its big data and overload of information, there will be so much ‘noise' out there that it will be much harder to sort the meaningful information from the less meaningful. We will need to become expert at picking up the important signals, regardless of how weak they may be. Although you might not have heard of the idea of sensemaking before, you probably do it all the time. As you read this book, you are sensemaking. As you finish this very paragraph, you might pause for a moment, consider its main idea, observe how you understand it, and then integrate the idea into what you already know. If you are working with a group, you would then articulate the ideas to others. Part of the problem with sensemaking is that it seems so darn obvious. ‘You want to teach me how to make sense of things? Are you serious? I've been doing that since I was a kid!' But as with many things that we do as humans, just because we've been doing it forever doesn't mean that we are doing it to the best of our abilities. I reckon it's possibly the most overlooked or misunderstood action in organisations today. It's common to see teams that are so overwhelmed by their daily workload that they seem to have either lost the ability to stop and observe how their landscape is changing, or they have lost the ability to articulate the changes to one another. Have you ever sat down and read the instructions for your smart-phone? Chances are you haven't; you just picked it up and started using it straight away. But you're possibly using less than 50 per cent of its capabilities. We do it all the time — we take things out of the box and start using them, never looking back. We have a bias for action, and for getting started on things straight away. But that approach will no longer serve us if we want to thrive in the VUCA world. We need to go back to the box, get out the instructions, and sit down and read them. And make sure we actually understand them. You'll see this is something of a theme in this chapter: to begin with, we need to slow down before we can speed up. If sensemaking is how we understand an uncertain world, it stands to reason that organisations that learn the art of sensemaking will have an unfair advantage in the VUCA world. They will be able to sense the nature of the game, its rules and how they are changing, as they play. And don't forget, this is an infinite game that we're playing. In alpine-style organisations, your survival depends on sensemaking. In your light and fast organisation, sensemaking should be happening all of the time. It can be used to look externally to learn about changing technology, changing markets, and changing competition, and it can be used internally, to look at your organisation's people, its politics and its culture. In your new world organisation, everybody needs to be doing it. It is not just a process relegated to the organisation's senior management and board, as it traditionally has been with old world organisations; nor should it only be the responsibility of those serving at the organisation's interface with the external environment. (Besides, new world organisations don't have clearly defined interfaces between what is inside and what is outside the organisation. In the VUCA world, with collaboration, transparency and community, ‘interfacing' is a constant.) The irony of course, is that sensemaking is the activity we least feel like doing when we actually need it the most. In the VUCA world, where cognitive dissonance, entropy and disengagement are the normal responses, it is our natural tendency to revert to what we know, and sensemaking it is not one of those things. We seek comfort in what we know to be true and to be certain — in the old world, that was reactivity and dependence. However, this leads us to rely on old habits and old ways of doing things, making us more rigid and less flexible. It's easy to see why sensemaking isn't something that comes naturally to expedition-style organisations. One of the unintended but most valuable benefits of sensemaking in an organisation is that it helps build the working relationships between team members. Because it is both iterative and interactive, it is a social exercise, and because it happens in the early stages of the work process, it is a great way for a team to become familiar with each of its members. In many ways, sensemaking is team building. (If a team-building event doesn't include sensemaking, then it's not really team building, it's just socialising — more on this in the third skill described in this chapter.) So, what does the sensemaking process actually look like? Dan Roam, one of the world's leading experts on visual thinking, describes his process in his book The Back of a Napkin. Although Roam's book was essentially produced to help people simply yet effectively illustrate business ideas in the boardroom environment, his key idea about the process of visual thinking forms a useful basis from which to learn the process of sensemaking. According to Roam, there are four main steps to visual thinking: Just as with sensemaking, this process shouldn't come as a surprise to any of us; after all, we do it all the time. Even the simplest of tasks — such as crossing the road with your young child — requires it. Think about it: When I cross the road with my daughter, Lilly, I hold her hand, stand at the kerb and look both ways before crossing. If I see a car, I then imagine whether we have enough time to cross safely before the car arrives. If I decide there is, I then show Lilly, ‘See, little one, it's safe to cross'— and then we're ready to move. Of course, Roam misses the final step, which, while not so important in the boardroom, is critically important in the VUCA world — and that's acting. So, sensemaking has five steps: Let's very quickly explore each of these steps in more detail. Roam describes looking as a semi-passive process of ‘taking in' the information surrounding us, and gives examples of ‘looking' questions: Of course, this sounds pretty straightforward and obvious, but when you break it down, there's actually quite a lot going on when we ‘look'. The first part to looking is the active, conscious part: it's where we consciously use our eyes to scan the environment surrounding us so as to be able to understand our context. We are seeking multiple sources of input: we are trying to gather as much information about our surroundings as we can. We have a thirst for data. The second part to looking is where we unconsciously follow an order of looking, which is orientation, position, identification and then direction. For example, when you enter a crowded room, without realising it you are intuitively identifying: If you are unable to instantly perceive any of these things, it's likely that something is amiss. Once we have looked and acquired all of the available information, we then start mentally laying it out, enabling us to make connections between the different items, to give it order, and allowing us to throw out what we don't need. Roam calls this ‘practising visual triage'. This leaves us ready to start the second component of sensemaking: seeing. Seeing is the conscious process that occurs in our brain once we have looked. It is only once our brain receives and processes visual information (in terms of orientation, position, identification and direction) that we start to see things. (Although this seems strange, we don't actually see with our eyes; rather, we look. It is with our brains that we see.) Seeing is the opposite of looking. Whereas looking is a process of exploring and gathering as much information as possible, seeing is a process of selecting and refining that information into things we can understand and recognise. That's why it's such a crucial component of the sensemaking process. The third step is imagining. Once you have looked at and identified what you are seeing, you need to think about why it is important. This is where your mind's eye comes to the fore, where you convert the visual images you are seeing into abstract concepts that you can manipulate in your brain. There are five ways of imagining what it is that you're seeing. Is it: This process of imagination has two particular uses. Firstly, it forces you to explore your interpretation in greater detail. Secondly, it requires you to decide how you will show your interpretation to others, which is the next step. The fourth step of the sensemaking process is showing the culmination of the previous three steps to your team members. This step is what makes sensemaking such a collaborative process. The reasons for doing this might be to inform them, to persuade them or to critique them — or perhaps all three. The last step is about testing your assumptions by transitioning into action. This is when you start exploring the environment, taking your ideas and testing them at the edges of the external world. The initial steps of acting are always tentative: are the assumptions correct? If we are confident, we then move: light and fast. Mark Twight describes how alpinists get ready for the final stage of sensemaking on the mountains: ‘They make seemingly random tentative probes, testing the mountain's weakness, before launching an all-out push.' So how do we decide whether or not to launch the ‘all-out push'? This leads us to the second skill we need to develop to become an alpine-style organisation — the skill of full-spectrum decision making. The great paradox of the VUCA world — remembering that the perfect storm of people, places and technology is largely of our own making — is that humans are not naturally equipped with the cognitive ability required to deal with the challenges of uncertainty and complexity. In chapter 3 we learned that cognitive dissonance, entropy and disengagement are the normal reactions to the VUCA world. And the quality of the decisions made by a person experiencing such mental malaise will be compromised. You might think that in an old world organisation this wouldn't be such a problem, because the levels of dependence always ensured decision making was sent up the chain to the top of the hierarchy. That, however, is a fallacy: someone will still have to make the decision, and the rate at which decisions will need to be made in the new world order means that a single or limited number of decision makers will be overwhelmed very quickly. Not to mention of course that the person responsible for making the decisions is human too, and will also be experiencing their own dissonance, entropy and disengagement. When we are in a state least suited to doing so, we are required to make increasingly difficult and complex decisions, and more of them. In the new world, we no longer have the luxury of time or the right amount of information (we will either have not enough, or way too much) to make decisions. Imagine yourself in a complex and highly volatile environment. Ambiguity and uncertainty is everywhere. And you need to make a decision about what to do. The information you are receiving is voluminous, leading you to experience a sensation of overwhelm. Additionally, the information you are receiving is incongruent with your expectations. (Just as it was for most people on 9/11.) ‘How can this be happening?' you ask yourself. At a time when you need to be making your best decisions, the human brain is least prepared to do so. And so rather than doing what we have done in the past, which is to focus on the quality of the decision made (in other words, the outcome — i.e. ‘Did we make the wrong or the right decision'), we need to focus on the quality of the decision-making process. There's a big difference between the two. We need to develop independent and interdependent people capable of making decisions either by themselves or within their teams (as opposed to passing it up the chain of dependency). When determining an appropriate course of action in an uncertain and ambiguous environment, everything else stems from the decisions that the individual and team make. In order to understand how the individual and team become independent and interdependent, we need to be aware of what's actually happening behind the surface every time a decision is made. To understand this, we need to look at how the human brain operates. More specifically, we need to understand the complex thought processes that enable the individual and team to employ a high-quality decision-making process. The past decade has seen significant advances in neuroscience's understanding of the interplay between the brain's neocortex and limbic system, and the conscious and subconscious (or unconscious, depending on which term you prefer) workings of our mind. Much of this understanding has been popularised in a number of recent New York Times bestsellers, the best known of which is Nobel Prize–winner Daniel Kahneman's book Thinking, Fast and Slow. Although initially applied to economic theory, Kahneman's work has much scope for application to the challenges we face in the VUCA world. Indeed, Daniel Kahneman goes as far as to describe organisations as being ‘essentially factories for making decisions'. The basic tenet of Kahneman's work is that the human brain has two ways of thinking: fast and slow. Fast thinking is quick, intuitive (it happens at the subconscious level) and often emotional. Slow thinking, on the other hand, is steady, deliberate and rational. Kahneman's key idea is that all of our thinking falls into one of these two categories. Fast thinking is energy efficient, but sometimes unreliable and often prone to systematic errors known as biases, or heuristics, and these can lead to a reduction in the quality of our decision-making process. Examples of fast thinking include the following: Using next to no mental energy, your brain was able to provide you instantly with the answers (or in the case of the whistling, you didn't have to think about the tune you were whistling). Kahneman refers to fast thinking as operating ‘automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control'. Slow thinking, on the other hand, uses a lot of energy — meaning the brain is reluctant to use it unless it's absolutely necessary — but it is very good at solving complex problems. Indeed, as you are reading this paragraph, trying to understand the difference between the two speeds of thinking, you are using slow thinking. Slow and fast thinking do not always operate independently of one another. Indeed, fast thinking is continuously generating suggestions (e.g. impressions, intuitions, intentions and feelings) for the slow thinking to consider and confirm. In the old, pre-VUCA world, when everything happened as we expected it to, the slow thinking simply adopted the suggestions of the fast thinking, with very little or no modification (and hence, limited energy expenditure). In the new VUCA world, however, our fast thinking is continually running into difficulty, because not everything is happening as we expect it to. We are required to call on our slow thinking with much greater frequency until we adapt to this new VUCA paradigm. Time and time again, our slow thinking will be activated when events are detected that are inconsistent with the model of the pre-VUCA world that our fast thinking has previously maintained. In that old world, people don't decapitate others on camera and post it on the internet, commercial airliners don't simply disappear off the face of the earth or get shot out of the sky by Ukrainian separatists, and companies don't spring up and grow to market valuations of $19 billion overnight. So, what to do? In short, the answer is we need to slow down before we can speed up. Just as Ueli Steck had been climbing for more than a decade before he set a speed record on the North Face of the Eiger, we need to understand and learn about ourselves and how we can improve the decision-making process. We need to be aware of where our rational, emotional and subconscious thinking sit in relation to the spectrum of fast and slow thinking. Once we are able to do this, and deliberately slow down or speed up our thinking as is required, we have mastered full-spectrum decision making. Figure 9.2 illustrates how they all come together. Figure 9.2: full-spectrum decision making Have you ever been faced with a stressful situation and heard yourself, or someone else, say, ‘Okay, just calm down and think about this rationally'? If you believe what you hear in the workplace then you'd be forgiven for believing that rational thinking is the only type of thinking that is important. Rational thinking is deliberate and steady — classic slow thinking. Yet, to ignore the emotional and subconscious components of thinking when making decisions would be foolhardy especially in the VUCA world. Emotional thinking at its most basic level seeks either pleasure or pain and is generally not easily regulated. Subconscious thinking is even less regulated (it is subconscious, after all), but can be incredibly influential and distort the facts in the decision making process (these are the biases or heuristics we referred to earlier). In order to make full-spectrum decisions, whether as individuals or in teams, we need to become better at identifying what influence these two components of fast thinking are having on us. Emotional thinking can sabotage both the individual and team decision-making process because emotions can often override logic, especially in volatile, uncertain and ambiguous environments. Having awareness of your own emotional thinking is referred to as emotional intelligence, and is described in the work of Peter Salovey, John Mayer and Daniel Goleman. There are four stages to developing emotional intelligence: If we can all understand the basic concept of emotional intelligence then we can learn to shift the emotional component of decision making from fast to slow thinking. If emotional thinking can override logic and lead to poor quality decisions, then subconscious thinking can secretly influence logic and lead to disastrous outcomes. As we have learned with regard to slow thinking, the brain tries to expend as little energy as possible when making decisions, and this means it has a preference for using shortcuts. But, as anyone who's ever spent much time in the mountains can attest, shortcuts often don't work. These shortcuts are the biases and heuristics that we referred to earlier. It is these shortcuts that are often responsible for contributing to poor decision making. In mountaineering, the most classic bias is known as Summit Fever. This is where a climber may be close to the summit and decides to press on despite the evidence that it is too dangerous to continue. The climber, so focussed on their goal of reaching the top (remember ‘goalodicy' from chapter 6), avoids the use of slow thinking, which would suggest they turn back, and instead listens to the subconscious bias that tells them that they are so close, and have invested so much, that they should continue to the top. In business you may have come across this bias, just by a different name — it's the sunk cost bias. There are a multitude of biases that affect the decision-making process of individuals and teams, but here are four common ones that you'll encounter repeatedly in the VUCA world: Again, if we can all understand the basic concept of biases and heuristics, and learn to identify the multitude of different subconscious biases that we are prone to, we will be able to shift the subconscious component of decision making from fast thinking to slow thinking. Combined with our ability to slow down and recognise the influence that our emotional thinking is having, this is the key to enabling individuals and teams to make full-spectrum decisions. So, we've learned about the two most important skills that we must have when operating in the VUCA world. As standalone skills they are incredibly important, but when combined with a final skill their efficacy can be elevated enormously to new levels, giving you an unfair advantage over everyone else. What's the final skill, you ask? You might not expect it, but we need to get more critical of ourselves and of our team members. Why? Let's have a look. In his excellent book Zero to One, PayPal cofounder Peter Thiel tells how in an earlier incarnation of his career at a New York law firm, he had noticed that despite the partners spending all day together, they had little to say to each other. This confounded Thiel, who found himself asking: ‘Why work with a group of people who don't even like each other?' As Thiel says, ‘if you can't count durable relationships among the fruits of your time at work, you haven't invested well — even in purely financial terms'. And although PayPal (now owned by eBay) is a relatively new organisation, this line of thinking has its origins in the old world, where one of the key organisational mantras was that we should all get along. After all, we spend so much time at work with our colleagues, it makes sense that we enjoy each other's company. To assist with this notion, a new industry specialising in team building was born. This industry focussed on helping organisations improve the interpersonal relationships and social interaction between employees. In a sense, it was about moving team members to the right end of a spectrum that moves from ‘not getting along' to ‘getting along', and up a spectrum from being critical of one another to not being critical. The notion of team building was often confused with team socialising. It was the work equivalent of Happy Families. It was all about creating harmony and removing discontent, with the core belief being that only a team working in social harmony could achieve good results. The industry offered such ‘classic products' as scavenger hunts, mini golf and even paintballing. Of course, there is a problem with these manufactured attempts at social cohesion. Common responses of most employees to news of imminent team-building events often include, in the following order: That's because most people see them as a waste of time. And for the most part, they are a waste of time. I am stunned to see the ubiquity of these forms of team building still in practice today. Good organisations spending good money on a wasted opportunity to really improve how a team of people can work together. This old world approach to team building has absolutely no relevance in today's VUCA world. The problem with old world team building is that getting along and getting critical are seen as polar opposites: a team that gets along is seen as good, and a team that doesn't get along, or one in which members are critical of one another, is seen as bad. But real teams in the new world order aren't necessarily the Brady Bunch of corporate. Team social harmony doesn't equal effective team performance. Why? Because concentrating on making people happy means an inability to give good critical feedback and unbiased reporting, which is, as we have just learned, essential in the sensemaking and decision-making processes. In the new world, team building should still be about getting people to get along but also, and more importantly, it should be about enabling us to question each other on our assumptions and beliefs. Of course, this isn't an open invitation for open and critical attacks on team members; rather, we should be encouraged to have open, healthy discussion about the work we are doing together and, rather than criticising, we should be critiquing one another. Both sensemaking and full-spectrum decision making are tools that can be employed to great effect by the individual, but their true potential in the VUCA world comes to the fore when the critiquing power of the entire team can be leveraged. That's when the sensemaking and decision-making processes reach the status of very high quality. And that can help lead us to success in the VUCA world. But of course, these tools by themselves are not enough. It's all good to be armed with the latest equipment, and to know how to use it, but there's also some stuff that you'll need to know about yourself, your team, and your organisation — and that's what we're going to look at in the next chapter.

CHAPTER 9

Three skills

Sensemaking

The process

Looking

Seeing

Imagining

Showing

Acting

Decision making

The neuroscience of decision making

Full-spectrum decision making

Being aware of our emotional intelligence

Being aware of our subconscious thinking

Getting critical