Moderation Matters

Power, Responsibility, and Style

Abstract

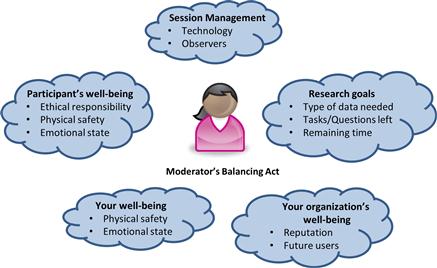

As the moderator of a user research session, you’re responsible for the competing needs of the participant’s emotional and physical state, your own emotional and physical state, your study’s research goals, overall management of the session, and the protection of your organization. Balancing all these needs requires empathy, flexibility, creativity, a sense of humor, and an aura of authority. These qualities combine with your moderating style to ensure that you can make your session as successful as possible, and that you can adapt as needed to any changing conditions.

Keywords

user research moderating style; new usability moderators; user research empathy; user research flexibility; user research creativity; user research sense of humor

1.1 “Are they laughing at me?”

I used to work at an institution of higher learning. We did a lot of usability testing, up to 120 studies a year. One particular day we had a client who wanted to test a website, but wanted their entire department staff to observe the testing. Our observation room sat 12 and it was mostly filled. Being late in the day, the observers were getting slaphappy after watching users identify the same usability problems over and over again. It was our last session of the day when we encountered a slightly more eccentric participant than normal.

As she was tackling the tasks, she was quite entertaining in some of her feedback, and you could hear, through the adjoining wall to the observation room, muffled commentary becoming louder. I proceeded to instant message my colleague in the room to have the observers keep it down, but by the time she read my note, it was too late. My participant’s eccentric nature had come out via an absolutely hysterical comment that I, as the moderator, had to literally bite my tongue to not laugh at. While I controlled my own reaction, a volcanic eruption of laughter could be heard through the wall. As my participant heard them, her face changed immediately, followed with “Are they laughing at me?”

I no longer wanted to laugh. I was paralyzed with “What do I do?” I lied. I told her no, they’re not laughing at her, but rather that everyone who has come in here today has had a similar experience with this task, so we’ll have to redesign the website. It was the best I could do at the time, but I’m not sure she believed me. During the next several tasks, there were no sounds from the observation room; they were as silent as she had become. At the end, I walked her out and apologized on behalf of the observers.

—Michael Dutton

1.2 Power and responsibility

Michael’s story emphasizes how important a role you have as the moderator of a user research session. Your position on the session’s frontlines means that when tricky, sticky, and unexpected situations arise, you’re the one who has to decide what to do and then take action.

When you encounter an awkward or uncomfortable situation with a friend or someone else you know, you can inform your response with your knowledge about that person. You rarely have any additional knowledge to help you when the same situation happens during a user research session. And, of course, you have additional complications to consider. During a session, your reactions as a moderator must balance the following competing needs (Figure 1.1):

![]() The participant’s emotional and physical states. Is she nervous or uncomfortable? Is she looking like she is unwell or experiencing physical discomfort?

The participant’s emotional and physical states. Is she nervous or uncomfortable? Is she looking like she is unwell or experiencing physical discomfort?

![]() Your emotional and physical states. Are you uncomfortable with anything happening in the session? Are you reacting to an allergen in the environment? Is there an external circumstance occurring that might threaten your physical safety or that of the participant’s?

Your emotional and physical states. Are you uncomfortable with anything happening in the session? Are you reacting to an allergen in the environment? Is there an external circumstance occurring that might threaten your physical safety or that of the participant’s?

![]() The study’s research goals. Are you measuring an experience, looking for issues that need to be fixed, or trying to understand the participant’s process?

The study’s research goals. Are you measuring an experience, looking for issues that need to be fixed, or trying to understand the participant’s process?

![]() General session management needs. Are your remote session technology and recording equipment working correctly? Are your observers behaving well, especially if they’re in the same room as you?

General session management needs. Are your remote session technology and recording equipment working correctly? Are your observers behaving well, especially if they’re in the same room as you?

![]() Protection of your organization. Are you ensuring that the participant leaves with a positive experience so she doesn’t say nasty things about your organization on social media? Are you doing your best to get feedback from participants that will help improve the experience for future users of your organization’s products or services?

Protection of your organization. Are you ensuring that the participant leaves with a positive experience so she doesn’t say nasty things about your organization on social media? Are you doing your best to get feedback from participants that will help improve the experience for future users of your organization’s products or services?

Throughout a session, this balance may shift and you, as the moderator, have to adjust accordingly. The way you handle a situation at the beginning of a session may be very different than how you’d handle the same situation later on, even with the same participant.

Take the example of the usability study session from Michael’s story. At the beginning of the session, his duty as the moderator was mainly to elicit feedback that satisfied the study’s goals. Some minimal encouragement may have been needed along the way to keep the participant content, but his larger concerns were to stay neutral and keep the observers engaged in the session. But as soon as the participant heard laughter from the adjacent room, she became uncomfortable, embarrassed, and all too aware that her performance was being watched.

At this point, the balance of competing needs shifted away from the session goals and more toward the participant’s emotional comfort. Because the participant’s comfort was at risk, Michael’s attention as a moderator had to focus less on collecting feedback and more on making sure that she was okay and would leave the session feeling comfortable (rather than upset at him or his organization). Under normal conditions, telling the participant that everyone else had the same experience with the task might have been considered biasing. But Michael sacrificed that data integrity to help the participant relax and to avoid tarnishing the reputation of his organization. Also, he needed to ease tension between himself and the participant for his own emotional comfort.

Finding the right balance of these needs can be difficult and stressful, especially if you’re new to moderating. There are times when you’ll feel pressure to help the participant—it can be painful to watch her struggle—but you may have to resist that urge and maintain neutrality so that the data you’re collecting are unaffected. On the flip side, sometimes you’ll feel pressure from the stakeholders to stick to your study plan but you’ll have to deviate from that plan to comfort an upset participant.

This responsibility is why you, as the moderator, are important. You have the power to impact both the study results and the participant’s emotional state. More than anyone else involved in the research, your interpersonal and troubleshooting skills can mean the difference between a successful session and an awful one. But, as we’ve learned from countless movies, this power comes with great responsibility. You’ll have to take that power and use it wisely in all kinds of common, tricky, and sticky situations. We hope this book will be your moderating Swiss Army knife: the right set of tools to help you deal with anything that comes your way during user research sessions.

1.3 The session ringmaster

Empathy. Flexibility. Creativity. Sense of humor. Aura of authority. To successfully handle tricky and sticky situations while moderating, you must embody and balance all these qualities. You may recognize these skills as being similar to those of a circus ringmaster. The ringmaster actively listens to and monitors everything that is going on around her, directs the audience’s attention, and controls the overall pacing and flow of the show.

Let’s talk about these qualities in more detail:

![]() Empathy helps you recognize what the participant is feeling. Remember that no matter what else you’re dealing with outside of a session—argumentative stakeholders, temperamental technology, travel problems, etc.—the participant is a person and not just a way for you to get feedback. Put yourself in her shoes and think of how you’d want to be treated if the positions were reversed. Be genuinely interested in her well-being and in what she has to say. Use your empathy to identify when she is upset or frustrated and respond in a sincere, compassionate way to help her feel comfortable again.

Empathy helps you recognize what the participant is feeling. Remember that no matter what else you’re dealing with outside of a session—argumentative stakeholders, temperamental technology, travel problems, etc.—the participant is a person and not just a way for you to get feedback. Put yourself in her shoes and think of how you’d want to be treated if the positions were reversed. Be genuinely interested in her well-being and in what she has to say. Use your empathy to identify when she is upset or frustrated and respond in a sincere, compassionate way to help her feel comfortable again.

![]() Flexibility is necessary because as these situations occur—a participant becomes sick or angry, an observer barges in, or technology fails you—you can’t just railroad your way through the study plan. Sticking stubbornly to your original plan may just exacerbate the situation, leading to uncomfortable participants and biased results.

Flexibility is necessary because as these situations occur—a participant becomes sick or angry, an observer barges in, or technology fails you—you can’t just railroad your way through the study plan. Sticking stubbornly to your original plan may just exacerbate the situation, leading to uncomfortable participants and biased results.

![]() Creativity or improvisation is called for when unexpected situations arise. In fact, we know a few improv actors who are great moderators. A very simple formula called “Yes, and …” underlies improv. The principle behind “Yes, and …” is to acknowledge and accept what you have to work with and build upon it rather than fight it. This concept is especially well-suited for user research activities. If a tricky or sticky situation arises, embrace it (flexibility, or the “yes”) and think quickly about how to handle it (creativity, or the “and …”). Creativity is not an easily learned thing, and for some it’s more natural than for others. But you can set up a framework conducive to creativity by embracing the improvisation mindset.

Creativity or improvisation is called for when unexpected situations arise. In fact, we know a few improv actors who are great moderators. A very simple formula called “Yes, and …” underlies improv. The principle behind “Yes, and …” is to acknowledge and accept what you have to work with and build upon it rather than fight it. This concept is especially well-suited for user research activities. If a tricky or sticky situation arises, embrace it (flexibility, or the “yes”) and think quickly about how to handle it (creativity, or the “and …”). Creativity is not an easily learned thing, and for some it’s more natural than for others. But you can set up a framework conducive to creativity by embracing the improvisation mindset.

![]() A sense of humor is important in unpredictable situations. When everything feels like it’s falling apart during a session, it’s better for you to laugh than cry! We don’t mean that you have license to be obnoxious or make inappropriate jokes to the participant—of course you need to stay professional. Rather, we mean that you should appreciate the humor of the situation but only on the inside. Try not to get upset or nervous if something doesn’t go as planned. Take a breath and remind yourself that you have the tools necessary to handle this. In the worst case, you’ll have a great story to share with your colleagues later (after removing any confidential information, of course).

A sense of humor is important in unpredictable situations. When everything feels like it’s falling apart during a session, it’s better for you to laugh than cry! We don’t mean that you have license to be obnoxious or make inappropriate jokes to the participant—of course you need to stay professional. Rather, we mean that you should appreciate the humor of the situation but only on the inside. Try not to get upset or nervous if something doesn’t go as planned. Take a breath and remind yourself that you have the tools necessary to handle this. In the worst case, you’ll have a great story to share with your colleagues later (after removing any confidential information, of course).

![]() An aura of authority means that, as the moderator, you must establish yourself to both the participant and the observers as the one in control of the session. Remember that you’re ultimately responsible for what happens here! Your body language and tone of voice are vital in establishing this authority. You must also be comfortable keeping the session on track. For example, if the participant is taking longer than you expected to show you her process during a contextual inquiry and you need additional feedback before the session ends, you must politely but firmly move on. Remember to balance your authority with your empathy so that the participant feels comfortable and confident while sharing her feedback.

An aura of authority means that, as the moderator, you must establish yourself to both the participant and the observers as the one in control of the session. Remember that you’re ultimately responsible for what happens here! Your body language and tone of voice are vital in establishing this authority. You must also be comfortable keeping the session on track. For example, if the participant is taking longer than you expected to show you her process during a contextual inquiry and you need additional feedback before the session ends, you must politely but firmly move on. Remember to balance your authority with your empathy so that the participant feels comfortable and confident while sharing her feedback.

While you put the participant in the spotlight during user research, don’t forget that you’re ultimately in control. Harness your inner ringmaster, plus or minus the top hat and coattails.

1.4 The science and art spectrum

You’re conducting a usability study. The participant is attempting a task that asks her to book a flight on a travel website. She gets to a page where she is considering the fares and says, “I don’t usually just book a flight. I typically explore the flight-plus-hotel combination deals and purchase one of them.”

Do you ask the participant to continue the original task of picking a flight? If you did, you’d be able to compare all participants’ data fairly. Or do you go off-script and follow the participant into whatever she would typically explore? You’d then get some valuable information about other areas of the website that you might not get from other participants.

You’ve just stumbled into one of user research’s great debates: Is moderating a science or an art? This debate usually arises in the context of usability studies when the participant is asked to attempt tasks with a product. Those who contend that moderating is a science believe that every moderator–participant interaction is an opportunity for bias and skewed data. Such moderators propose only interrupting participants during tasks if absolutely necessary, and keeping those interruptions confined to minimal phrases, or what Dumas and Loring (2008) refer to as “acknowledgement tokens” like “so” and “mmhmm.” Even if the participant is upset or distracted, your interaction with her would not change.

We don’t see the art and science approaches as a binary choice, but rather as the endpoints of a spectrum. Depending on the study goals and method, your approach may fall anywhere along that spectrum.

Because the majority of studies we’ve conducted have been formative (where the goal is to improve and learn rather than measure), our approach leans toward the art of moderating. This approach allows for more natural interactions with participants and, in our experience, lets you be more responsive when the unexpected occurs and acknowledgment tokens alone won’t cut it. In types of user research other than usability studies, there is an even stronger need for there to be some art to moderating. A certain flexibility level is fundamental for moderating those methods. For example, an interviewee may raise a topic relevant to your study goals that you had not originally planned on discussing, and you’d like to follow up. Or during a contextual inquiry, you may not anticipate how the participant will do some of her work, so you may need to muster up some on-the-spot questions about what she is doing.

We’ve found that the science approach works best for summative research (where the goal is to measure or validate a product) and when biometric or eye-tracking devices are used. However, even for summative research, you need to prioritize the participant’s well-being, even if it means sacrificing your data’s integrity. For example, if the participant starts crying during your summative usability study, you should respond compassionately instead of maintaining your neutral acknowledgments. While this may mean your task time measurements or other metrics may be affected, your ethical priority is toward the participant.

Where your approach should fall on the science/art spectrum depends on varying contexts, such as:

![]() The type and nature of the research—is it a usability study, contextual inquiry, or an interview? While bias is a concern for all methods, influencing participant behavior during usability studies or contextual inquiries might be a bigger concern than influencing attitudes stated in an unstructured interview.

The type and nature of the research—is it a usability study, contextual inquiry, or an interview? While bias is a concern for all methods, influencing participant behavior during usability studies or contextual inquiries might be a bigger concern than influencing attitudes stated in an unstructured interview.

![]() If it’s a usability study, is it summative or formative? A summative study requires strict assessment, usually measuring the user experience with metrics like task time and task success. Interruptions and exploratory questions may come at a cost in data quality. A formative test is meant to be more exploratory and anecdotal, so there is usually room for more conversation and creative follow-up tasks/questions.

If it’s a usability study, is it summative or formative? A summative study requires strict assessment, usually measuring the user experience with metrics like task time and task success. Interruptions and exploratory questions may come at a cost in data quality. A formative test is meant to be more exploratory and anecdotal, so there is usually room for more conversation and creative follow-up tasks/questions.

As we cover specific situations and recommendations later in this book, we’ll be explicit about any assumptions we’re making about the type of research and its goals. We’ll also explain the trade-offs you must consider and the potential outcomes of your choices. Feel free to adapt our advice to align with your own philosophy and circumstances, and use it to guide you in making more informed decisions.

1.5 Your moderating style

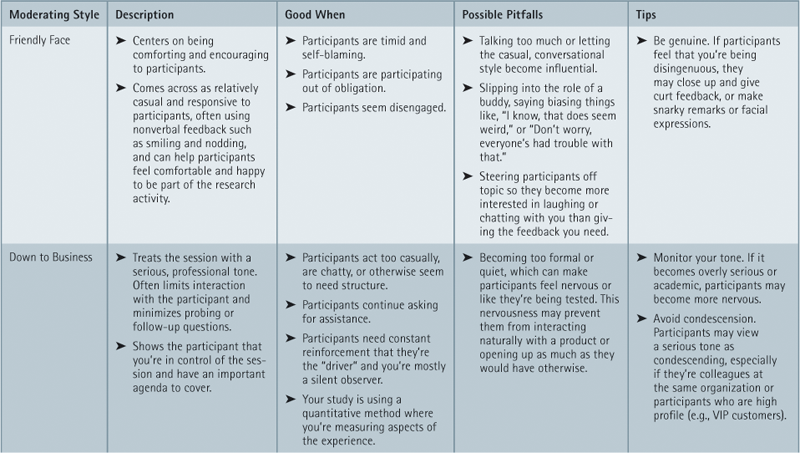

Moderating isn’t just about controlling the session and responding to any situations that occur. It’s also about the approach you take and the interpersonal skills you use when interacting with the participant. We define this approach as your moderating style. Just like how people come in all shapes, sizes, and combinations of qualities, so do our moderating personas.

Your style of interacting with participants is a combination of your core personality traits and the disposition you take while moderating. Your style may involve a combination of two or more characteristics, such as sociable, friendly, relaxed, lively, jovial, detached, business-like, quiet, inquisitive, alert, eager, dutiful, respectful, controlled, or subdued. Perhaps your natural style of moderating is friendly, but quiet and business-like. Or relaxed, yet respectful and inquisitive.

Think about what your natural moderating style is like. In your ideal session, with your ideal participant, how would you interact with her? What “vibe” would you be sending? Once you’ve identified your style, you’ll be able to recognize how your behavior might come across to different types of participants.

Table 1.1 lists some of the different moderating styles we’ve seen and used in the past, defines their characteristics, and warns about potential biases and pitfalls that come with them. Of course there are variations and gradations of each style, but these hit the key differences.

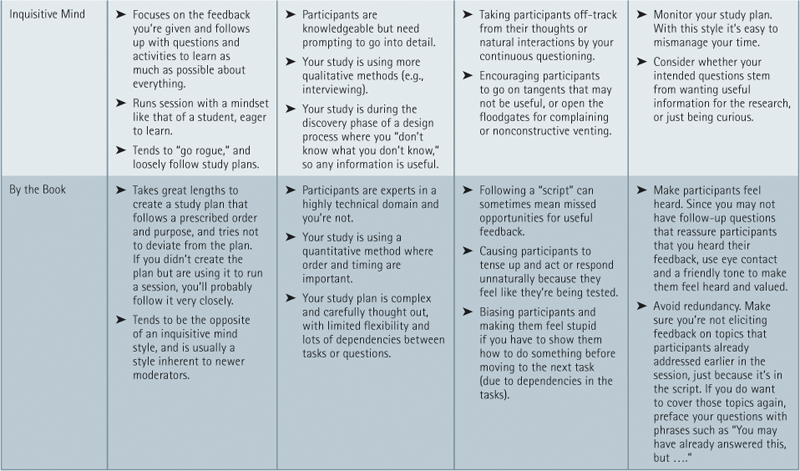

As you can see from Table 1.1, there are advantages and disadvantages to every moderating style. There is no single ideal moderating style—the style that you use can and should change from study to study, session to session, or even during the course of a session. Also, these styles are not mutually exclusive. Figure out what kind of style (or styles) will work best with your research goals in a particular study, and be flexible if the participant or situation calls for it.

1.6 Effective adaptation

To move beyond your natural style and become a truly excellent moderator, you must learn to adapt your style when necessary. Much like Sun Tzu’s The Art of War (n.d.), the art of moderating requires recognizing and responding to changing conditions. The “Yes, and …” approach calls for rolling with the punches. Likewise, your preferred moderating style may not be suitable for a particular kind of study, participant, or situation, and you may have to transition to another on-the-fly. This is when your flexibility is really put to the test!

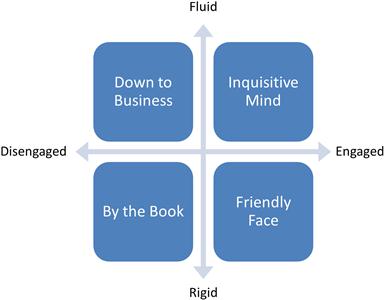

The best style to use depends both on how you need to interact with the participant (as discussed in Table 1.1) and where your study goals fall on the quadrant shown in Figure 1.2. Each style falls somewhere within the range of rigid versus fluid (based on your research goals and how much you need to follow a prescribed structure of your study plan) and engaged versus disengaged (how you need to interact with the participant at any given time).

Figure 1.2 Different moderating styles are appropriate depending on your research goals, how prescribed your study plan is (fluid to rigid), and how you want to approach the participant (engaged vs. disengaged).

You’ve read about the differences between moderating styles in Table 1.1, but let’s hash out a more detailed example here. Consider a contextual inquiry where you have a chatty participant who you’re trying to keep focused on demonstrating her workflow. Contextual inquiries are typically fairly fluid, and you’re a fairly friendly and casual moderator, so you’ve started with a style similar to Inquisitive Mind. However, given the participant’s talkativeness, continuing to be so informal and familiar could create issues. The participant may become even more chatty and off-topic, pulling her away from the natural workflow you’re trying to observe. The session may quickly snowball into an interview or conversation. The best way to adapt here is to transition to a Down to Business style with the goal of slightly disengaging from the participant. You don’t want to disengage so much that the participant becomes uncomfortable, just enough so that she knows you’re there for the serious business of watching her work.

Conversely, other situations may require you to draw a participant out and build engagement. Consider a fairly scripted interview where the participant is quiet and reserved. She seems like she is either shy or nervous about the session. Even if you’re more of a By the Book moderator, you may need to turn on the Friendly Face to help her feel more comfortable. A genuine smile and sincere tone of voice can help pull the participant out of her shell without biasing her feedback.

There is no precise way to pinpoint a participant’s or moderator’s personality, making it difficult to give one-size-fits-all advice for moderating. But our hope is that we’ve made you more aware of different moderating styles and how these styles can impact a session. To be truly effective you need to adapt and switch to other styles as needed. Being aware of moderating styles and their comparative strengths and weaknesses will help you shape and polish your own approach.