Reforming Education in the Caribbean

From Policy to Transformative Leadership

Summary

Chapter 4 claims that Caribbean systems of education experience some of the same multi-dimensional challenges as many of its global neighbors. According to the author, educational leaders and policy makers in the Caribbean should consider the thinking of certain scholars who advocate for critical theory approaches to leadership, which can effectively address these challenges.

Education, the beyond all other devices of human origin, is the great equalizer of the conditions of men, the balance wheel of the social machinery (Horace Mann 1848).

Introduction

The effectiveness of government-sponsored education in the Caribbean is the subject of concern for a wide range of stakeholders, including local and regional education organizations, and governmental and nongovernmental entities. The region joins other nations who are critically examining the role and impact of these systems on achieving national goals and improving the human condition of its citizens. Quality of life, economic development, and viable democracies are inextricably linked to effective systems of education. In 1954, Chief Justice of the United States affirmed the critical role of education in the country’s democracy when he rendered the following ruling in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, Brown vs. the Board of Education:

Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. Compulsory school attendance and the great expenditures for education both demonstrate our recognition of the importance of education to our democratic society. It is required in the performance of our most basic public responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is the very foundation of good citizenship.1

Furthermore, there is evidence for concern given disparities in individual and group educational experiences despite decades of efforts to reform, and in some cases transform, ineffective systems.

Education policy makers expend enormous amounts of resources—human and financial—engaged in policy development aimed at improving educational systems, with increasing focus on student learning outcomes. Nonetheless, that state of education in many places around the globe is in crisis, which is characterized by, but not limited to issues related to teacher quality, student readiness for postsecondary education, and educational equity. The notion of equity is differentiated from the concept of equity, as it necessarily attributes responsibility to organizational structures that give birth to and nurture educational disparities. As such, policy makers are encouraged to specifically consider education reform efforts from a structural framework.

In response to persistent concerns which threaten the economic health of communities around the world, policy makers continue to identify relevant problems that continue to challenge systems of education, including their impact on the students they serve. In consultation with a wide range of stakeholders, research is ongoing, policy alternatives are generated, adopted, and assessed for impact. Despite policy formulation developed to improve educational outcomes for learners, problems and inequities persist, which leads to a different path of examination—namely leadership. Transformative leadership for education reform in the Caribbean is the focus of this discussion. Psychologists Coby and Damon (2009) have been quoted as saying, “The course of society is largely determined by the quality of its moral leadership” (p. 69). Transformative leadership that leads to sustainable and effective educational reform in the Caribbean may also be determined by the quality of its moral leadership.2

The Caribbean is part of a far reaching phenomenon that highlights systems of education that fall short of quality education for all of its citizens. The region is joined with other political economies around the globe, as it continues to examine the juxtaposition of education, politics, and democracy. In 1990 delegates from more than 150 countries joined with representatives from nearly 150 governmental and nongovernmental agencies for the World Conference on Education for All (March 5–9), in Jomtien, Thailand. The aim of the conference was to make primary education accessible to all children and to massively reduce illiteracy before the end of the decade (UNESCO).3 At the conference, delegates adopted a World Declaration on Education for All, and reaffirmed the idea that education is a fundamental human right. The goals for the subsequent Framework for Action to Meet the Basic Learning Needs by the year 2000 were clearly articulated to include universal access to learning; a focus on equity; emphasis on learning outcomes; broadening the means and the scope of basic education; enhancing the environment for learning; and strengthening partnerships by 2000.

In 2000, governments from 164 countries came together in Dakar, Senegal, for the World Education Forum and reported on the results of Education for All efforts since 1990. Miller (2014) asserts that the vision for the Education for All declaration was “simple and powerful”—affirming the right of all children, youth, and adults to be afforded educational opportunities that meet their basic learning needs (p. 1). Referencing the Caribbean specifically, Miler asserts that Universal Primary Education has been a focus of Caribbean governments for many years, at least rhetorically, and agrees with evaluation of Education for All efforts which have been described as falling short of their goals as summarized in UNESCO’s EFA Summary Report (EFA Global Monitoring Report 2015).4

In response to problems plaguing their system of education and similar to other regions of the world, the Caribbean has engaged in multiple attempts to reform education over the course of the past two decades. Failed efforts caused Jules (2014) to revisit the question, what is the purpose of education in the Caribbean? Jules asserts that many of such unsuccessful reform initiatives amounted to projects promoted by multilaterals and benefactor organizations in accordance with established paradigms. Jules recognizes the implications of the internalization of education in a globalized world, and notes the shift in the guiding questions from what should be taught to what are the skills and competencies required for any area of knowledge?

The future of education in the Caribbean should not be discussed in isolation of a guiding philosophy according to Jules, and the Statement of the Ideal Caribbean (CARCOM) Person and the UNESCO Imperatives for Learning in the 21st Century, which were presented for inclusion in education reform discussions. The philosophical foundations for the ideal CARCOM person are: love life; emotionally intelligent; environmentally sensitive; democratically engaged; culturally grounded and historically conscious; multiple literacies; gender and diversity respectful; and entrepreneurial capable.5 As transformational leaders identify the next phase of educational reform efforts, this cultural context may support relevance and sustainability.

The Caribbean’s Diverse Landscape

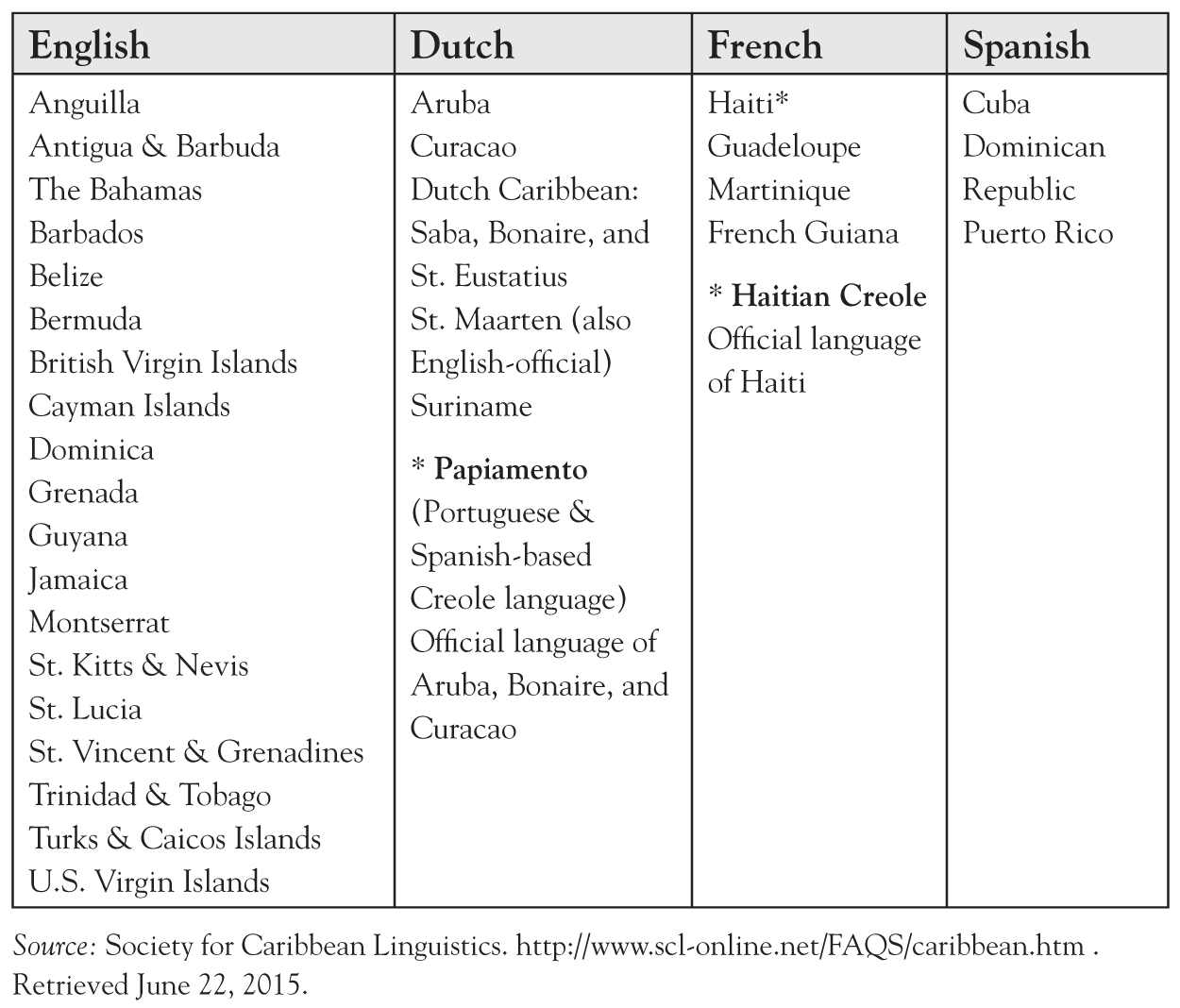

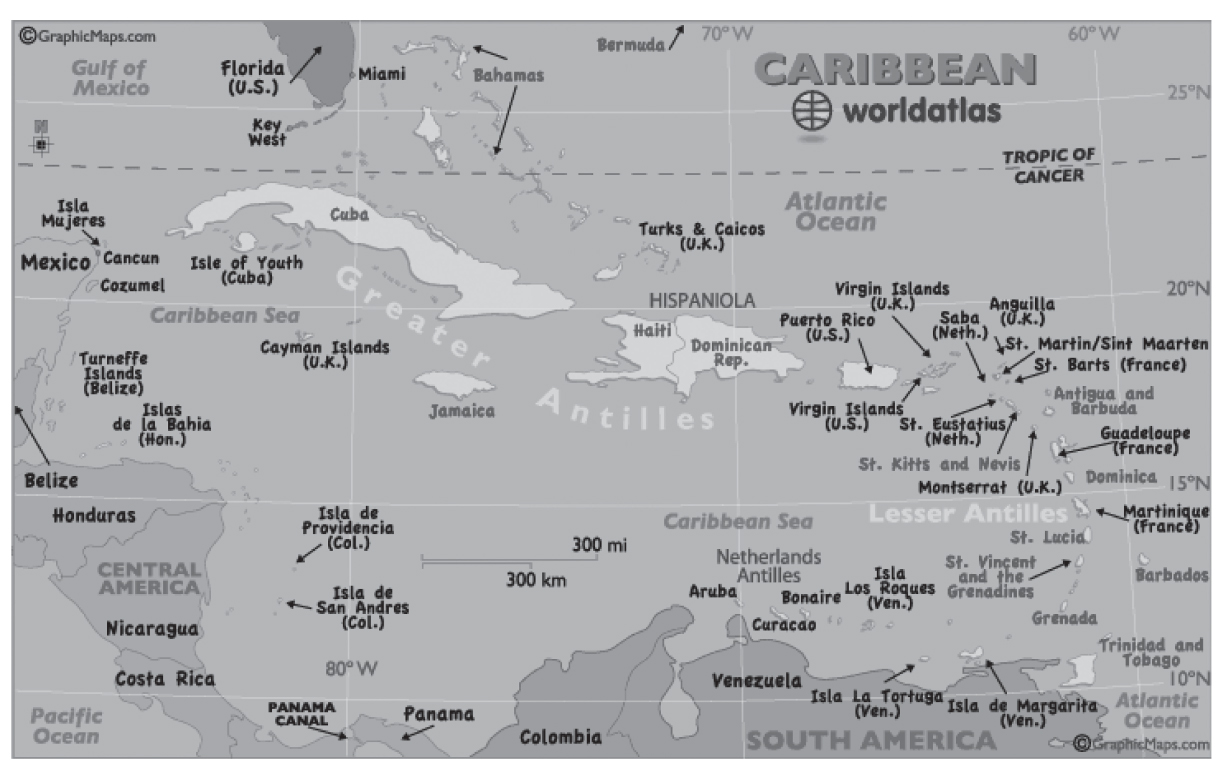

The Caribbean has been defined differently over history as being comprised of Dutch-, English-, French-, and Spanish-speaking territories, as illustrated in Table 4.1. Figure 4.1 provides a geographical illustration of the region, which consists of 31 distinct political entities.

Table 4.1 Countries of the Caribbean (also known as the West Indies and the Antilles) arranged by official language

Figure 4.1 Map of the Caribbean

Source: World Atlas. http://www.worldatlas.com/webimage/countrys/carib.htm. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

The Caribbean as Global Partner in Pursuit of Education for All

For the Caribbean, the United States and elsewhere around the globe, education remains a key strategy towards upward mobility and economic strength. As the world becomes “flat” and increasingly interdependent, and as geographical lines are being erased, both literally and figuratively, shared global concerns around the notion of an educated citizenry cross lines of sovereignty. The Caribbean need only look a relatively short distance to its North American relative to witness shared concerns and equally robust calls for educational reform, which have been underway for decades with the goal of promoting student achievement and strengthening global competitive position through educational excellence and ensuring equal access. Although education is primarily a State and local responsibility in the US, the federal government has a significant role in its provision to citizens, and overall educational reform.

Errol Miller has written extensively on the subject of education in this region of the world (1992, 1994, and 2010; www.mord.mona.uwi.edu/staff/view.asp?pid=10227). Miller notes that despite political dependency, British influence on education in the Caribbean has diminished significantly since the late 1950s. He further asserts North America’s growing influence in this area, which was one impetus for this writing that is somewhat comparative in nature. Given that assertion, it may be instructive to offer brief comparisons and contrasts between the two regions.

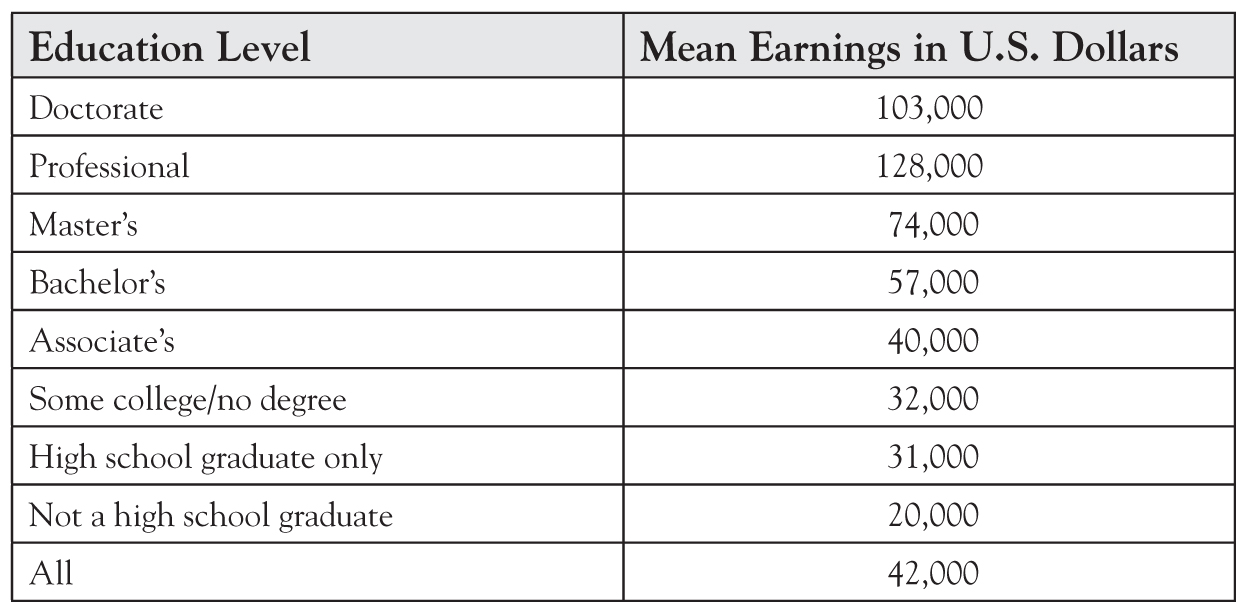

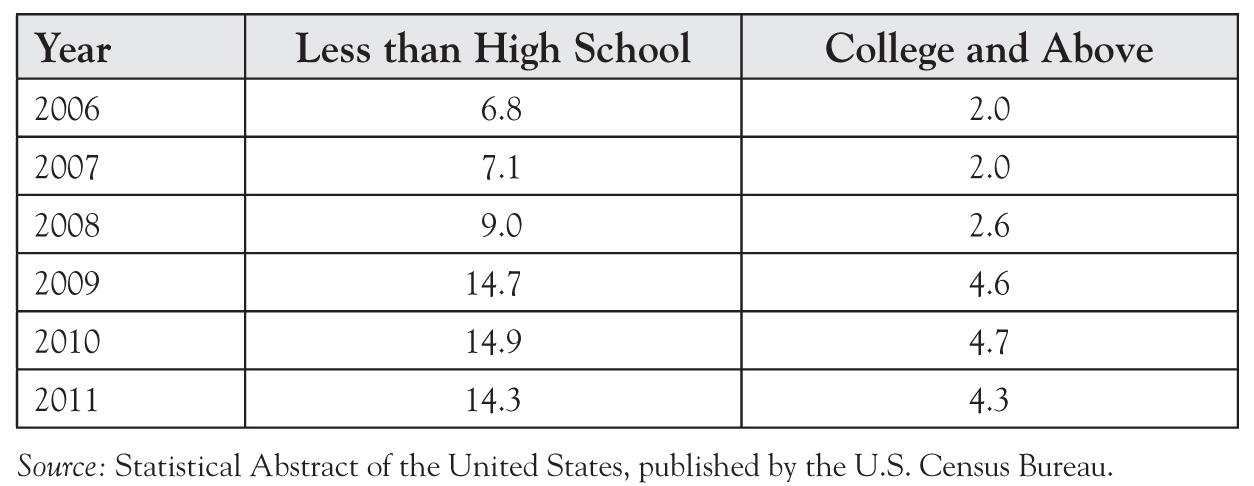

Like the United States, the Commonwealth Caribbean provides free public education to its citizens up to 15–17 years of age, depending on the territory. Miller (1999) acknowledges that there are similarities in the challenges confronting Caribbean and U.S. systems of education. With regard to education reform, he makes the point that the Commonwealth Caribbean (also commonly referred to as “English-speaking Caribbean” is comparable to more developed countries in their provision of education to its population. (Commonwealth Caribbean Education in the Global Context, p. 4). In common with other developing and developed nations, the Commonwealth Caribbean and its citizens recognize education as providing the greatest assurance for socioeconomic advancement. In the US, for example, the relationship between education, income disparity, and unemployment is clear. Simply stated, the more education one attains, the more income they accrue and the less likely they are to be unemployed (see Tables 4.2 and 4.3 for illustration).

Table 4.2 Mean earnings by highest degree earned in dollars: 2009

Table 4.3 Unemployment rates by educational attainment: percentage (US Bureau of Labor Statistics)

In the United States, social policy discussions, widespread education reform initiatives, and grassroots activism are converging with increasing focus on quality of education for all citizens with an emphasis on equity. Although the purpose of education is still debated in some societies and countries, Huitt has identified three primary purposes of education, which include the development of one’s purpose in life, the development of one’s character, and the development of competence.6 The economic and social impacts of an educated citizenry correlates with a productive citizenry.

In the 1954, the United States landmark Brown vs. the Board of Education case, the Supreme Court ruled that, “Segregation of students in public schools violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, because separate facilities are inherently unequal.” (Oliver Brown, et al. v Board of Education of Topeka, et al., 347 U.S. 483 (1954). More than fifty years later, there is renaissance movement of sorts to reposition the concept of equality in education at the top of political, social, and community agendas in the agenda. This is discussed in the edited book, Quality Education as a Constitutional Right (Perry, Moses, et al. 2010), which presents a serious appeal for the transformation of public education in America. With historical foundations, the authors present a cogent and compelling argument for youth involvement, the role of U.S. Constitution, and the unwavering pursuit of educational excellence for all citizens, as the prerequisites for real and sustainable transformation.7

Under the auspices of the U.S. Education Department, policy discussions and legislation focus on the promotion of student achievement, educational excellence, and equality on behalf of national security persists. The very mission of the Education Department is to “promote student achievement and preparation for global competitiveness by fostering educational excellence and ensuring equal access.” Established in 1980 by combining offices from several federal agencies, the Department of Education employs more than 4000 employees and has a $68 billion budget to set policies on federal financial aid for education, and distributing as well as monitoring those funds; collecting data on America’s schools and disseminating research; focusing national attention on key educational issues; and prohibiting discrimination and ensuring equal access to education.8

No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act was signed into U.S. law in 2002, which mandated standards-based education to improve student achievement. The Act required states to develop assessments in basic skills to qualify for federal school funding. The Act does not assert a national achievement standard, which is left up to individual states to develop their own standards. This perpetuates inequality in education. This expanded federal role in public education involves annual testing, annual academic progress, report cards, teacher qualifications, and funding changes.

NCLB Act requires all public schools receiving federal funding to administer a state-wide standardized test annually to all students. This means that all students take the same test under the same conditions. Schools that receive Title I funding through the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 must make adequate yearly progress (AYP) in test scores. If the school’s results are repeatedly poor, subsequent steps are required to be taken to improve the school. The Act also requires states to provide highly qualified teachers to all students, although each state sets its own standards for what counts as highly qualified. Similarly, the act requires states to set “one high, challenging standard” for its students, and these curriculum standards must be applied to all students, rather than having different standards for students in different cities or parts of the state—which, in its absence, results in inequitable systems of education.

To address failed policies, persistent achievement disparities between low and high wealth communities, and the complexity of education in a diverse twenty-first century global society, the U.S. has implemented other targeted educational policy initiatives including the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans; White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for Hispanics; White House Initiative on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders; White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities; and White House Initiative on American Indian and Alaska Native Education.9

In response to disappointing results of NCLB, a recent movement to reform public education in the U.S. involves the notion of a Common Core, which is comprised of a set of national standards that aim to replace the wide range of individual state standards, address concerns involving teacher preparation, reform instruction, and change systems of assessment and accountability. Despite this and other large-scale efforts to improve systems of education, educational leaders, policy makers, and other stakeholders recognize that a strong Common Core and other targeted strategies are not enough to address persistent and systemic problems that challenge the future of the developed world. Increasingly, the focus is being shifted to educator and leader preparation.

In comparison, the Caribbean has its own compelling narrative and history of actions aimed at education reform, of which many parallel concerns and efforts are underway in other parts of the globe. As is the case in other nations, the Caribbean is beginning to increase its focus on outputs as opposed to a myopic focus on inputs. Education inputs include such variables as school autonomy, school choice, funding, pupil-teacher ratios, and years in school. Outputs include cognitive skills (learning as measured by standardized tests) and other educational outcomes including graduation rates, literacy, and employment. While outputs are important measures of educational effectiveness, policy makers are cautioned against relying too heavily on these measures. Much of outputs that are measured represent only part of why public education exists. Specifically, public schools also serve to promote the goals of civic responsibility, cultural awareness, personal freedom, and self-sufficiency. Acknowledging the validity of inputs in educational policy and reform conversations may lead to more comprehensive reform efforts as it considers the role of other factors in student achievement such as structural social, economic, and educational variables. (Rice 2015).10

The Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), and Ministries of Education collaborated in 1991 to develop their Education Reform Strategy in concert with other significant international and regional education reform efforts. The OECS is comprised of nine states that include Antigua and Barbuda; Anguilla; British Virgin Islands; St. Kitts and Nevis; Montserrat; St. Vincent and the Grenadines; Commonwealth of the Dominican Republic; Grenada; and St. Lucia.

Using conventional policy generative methods, the OECS undertook a strategic process that began with an analysis of the region’s education systems, interacted with chief education officers of the OECS countries, consulted with a broad cross-section of stakeholders in each country, and conducted extensive research including literature reviews before making any policy recommendations. An OECS Education Reform Strategy emerged and included the following strategies aimed at improving educational outcomes in the region:

1. Strategies for Harmonizing the Education Systems or the OECS

2. Strategies for Reforming Early Childhood Education

3. Strategies for Reforming Primary Education

4. Strategies for Reforming Secondary Education

5. Strategies for Reforming Tertiary, Continuing, and Adult Education

6. Strategies for Reforming the Terms and Conditions of Service for Teachers

7. Strategies for Reforming the Management and Administration of the Education System

8. Strategies for Reforming the Financing of Education

9. Strategies for the Reform Process 11

Educational Leadership for Transformation

As this contribution is largely concerned with the intersection of educational reform and leadership, it is useful to take a closer look at OECS’s Strategies for Reforming the Management and Administration of the Education System in particular. The rationale for the strategy takes the position that the management and administration of education within free, open, and democratic societies should both reflect and advance the precepts and ideals of freedom and democracy in the Caribbean. In concurrence with conventional approaches to sustainable change and reform efforts, the management and administration of education should be characterized by shared decision making that includes broad representation; continuous discourse and consultation among stakeholders; intermittent discussion and re-negotiation of goals, mission, and methodologies; full access to public information; provision for leadership capacity building and a climate for the self-actualization of individuals, which would include adequate and appropriate training in management and administration for school personnel, and comprehensive public accountability.12

To move beyond policy implementation and toward transformational leadership for sustainable reform, management and administration will be compelled to transcend transactional leadership thinking and acting, which generally aim to keep systems running with lesser focus on strategic visioning, which may also involve taking risks. In contrast, transformational leaders engage in thought and action that can lead to radical change—to effectively address the challenges of education in the Caribbean in the twenty-first century. Educational leaders who seek to move beyond policy to transform their schools, communities, and region, are increasingly focusing on the notions of collaboration with an unwavering commitment to high performance teams that foster high levels of student learning and structural effectiveness and efficiency.

The impact of leadership on student learning has long been a domain of interest for educators, policy makers, and other stakeholder groups. It is limiting to think education reform efforts begin and end with policy formation. Letihwood, Louis, et al. (2004) examined the influence of leadership on student learning and asserted two noteworthy claims: 1. leadership is second only to classroom instruction among all school-related factors that foster student learning in school, and 2. the effects of leadership are generally most significant where and when they are needed most. Their research findings have implications for educational reform in the Caribbean as they advocate for moving beyond “models” of leadership to affect school change. Instructive for educational reform in the Caribbean, they promote leadership agility that considers organizational context and the students it serves. Leithwood, Loius, et al. also consider the policy context, which is necessarily at the nucleus of large-scale educational reform efforts.

The prevalence of a leadership-learning connection is accepted by many, however the Learning from Leadership Project (Leithwood, Louis et al. 2004) provides evidence of how leadership influences student achievement. The project reminds education reformers of the indirect impact of leaders on learners through their influence on people and the organizational environment. It not only supports notions of educational priorities that include teachers, but also highlights the importance of the internal and external professional community. Finally, the project acknowledges the need to discover more about what leaders do in addition to the nature and influence of those behaviors and practices.13

To create and sustain transformative systems of education in the Caribbean (and beyond) will require deliberate actions at the systems and local levels. Investment in leadership development needs to be part of policy implementation strategies as there are specific leadership competencies needed to transform systems and organizations. Widespread evidence supports the position that effective educational leaders possess personal qualities that foster a culture of excellence for all students under their auspices. To that end, they believe and communicate that all students can achieve at high levels and hold themselves and others accountable for student success. Transformative leaders are evidence-driven and use data to set goals and achieve student learning. Transformative leaders leverage their deep knowledge of curriculum, instruction, and assessment to improve student learning and align strategies accordingly. They have a unique ability to develop staff, share leadership, and build strong school communities. They additionally know how to effectively manage resources and operations to advance student learning outcomes.

Early studies examining the nexus of educational leadership and transformation include the work of Murphy (1994), which highlights the critical role of principals in promoting the success of teachers; shared governance and decision making; cultivating strategic relationships; facilitating the creation of a shared vision; allocating resources in alignment with the shared vision; providing information for teacher empowerment; facilitating the professional development of teachers; and managing educational reform.14 Leithwood and Jantzi (1999) researched the effects of transformational leadership on organizational climate and student engagement. Their study included survey data from more than 1,700 teachers and nearly 10,000 students. The study explored the concept of transformational leadership in school contexts which described it as representing the transcendence of self-interest by the leader and his/her followers.15 The researchers developed a model of transformational leadership using six domains: building school vision and goals; providing intellectual stimulation; offering individualized support; symbolizing professional practices and values; demonstrating high performance expectations; and developing structures to foster participation in school decisions.

The definition of transformative leadership as offered by Bennis’ (1959) definition of transformative leadership as one’s ability to “reach the souls of others in a fashion which raises human consciousness, builds meanings and inspires human intent that is the source of power” (Dillard 1995: 560).16 The Caribbean is positioned to join her global neighbors in authentic and contextually-based efforts to transform education in the region. Bold and less-fearful leadership in policy, governmental and nongovernmental arenas will be required, however, to develop and implement meaningful policies.

Conclusion

If, as Horace Mann asserted in 1848 education is the balance wheel of societies, a new kind of selfless and forward-thinking leadership will be needed. Welner and Carter’s (2013) describe an “opportunity gap” indicator to reframe how educational leaders, policy makers and others should examine educational inequities.17 Government leadership can address structural issues, including the development and support of teachers, by investing in the preparation of effective school leadership. Quality school leadership is particularly relevant in high-poverty communities where leadership stability may have an even greater impact. This type of leadership is necessarily deliberate in its aims to close the opportunity and achievement gaps, which are said to be interrelated. This type of leadership is also critical and may be contrary to convention.

Caribbean educational leaders and policy makers should consider the thinking of certain management and leadership scholars who advocate for critical theory approaches to leadership, which Western (2008) discusses through the four lenses of 1. emancipation; 2. depth analysis, 3. looking awry; and 4. systemic praxis.18 Western defines a critical approach to leadership as:

• looking for new possibilities and positive implications for social action;

• providing critical account of historical and cultural conditions;

• engaging in critical re-examination of the conceptual frameworks used; and

• confronting alternative social explanation through analysis of their strengths and weaknesses, but then illustrating capacity to synthesize and incorporate their insights to strengthen their critical foundations (p. 9).

Caribbean systems of education are experiencing some of the same challenges as many of its global neighbors. In particular, some communities are struggling with serious issues of access and equity, which will require new approaches to policy making and implementation, in particular leadership. What has been offered is additional ways to engage in a serious discussion that has serious implications for a growing region.

Notes

1. Supreme Court of the United States, Brown v. Board of Education (347 U.S. 483), 3. In Perry, T, Moses, R.P., et al. (2010). Quality Education as a Constitutional Right. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. (p. 99).

2. Johnson, C. (2009). Meeting the Ethical Challenges of Leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. (p. 69).

3. 2000 World Conference on Education for All. UNESCO EFA Global Monitoring Report. www.unsco.org. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

4. Miller, Paul. (2014). Education for All in the Caribbean: promise, paradox and possibility. Research in Comparative and International Education 9, November, pp. 1–3.

5. Jules, D. (2010). Rethinking Education in the Caribbean. Caribbean Examinations Council. www.cxc.org. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

6. Huitt, W. (2004). Moral and Character Development.

7. Perry, T., Moses, R.P., Wynne, J.T., Cortes, Jr., E., and Delpit, L (2010). Editors. Quality Education as a Constitutional Right. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

8. United States Department of Education. www.ed.gov. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

9. The United States Department of Education. www.ed.gov/about/inits/list/index.html. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

10. Rice, J.K. (2015). Investing in Equal Opportunity: What Would it Take to Build a Balancing Wheel. National Education Policy Center. School of Education: University of Colorado Boulder.

11. The Organization of Eastern Caribbean States. www.oesc.org. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

12. Ibid.

13. Letihwood, K., Louis, K.S., Anderson, S. and Wahlstrom, K. (2004). Research on How Leadership Influences Student Learning. The Wallace Foundation.

14. Murphy, J. (1994). Transformational Change and the Evolving Role of the Principal: Early Empirical Research. AERA, April 1994. ERIC Document Number ED 374 520, pp. 1–50.

15. Leithwood, K. and Jantzi, D. (1999). The Effects of Transformational Leadership on Organizational Conditions and Student Engagement with School. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (Montreal, Quebec, Canada, April 19–23). ERIC ED 432 035, 34 p.

16. Dillard, C.B. (1995). Leading with Her Life: An African-American Feminist (re)-Interpretation of Leadership for an Urban High School Principal.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 31(4): 539–563.

17. Welner, K.G. & Carter, P.L. (2013). Achievement Gaps Arise from Opportunity Gaps. In Closing the Achievement Gap: What America Must Do to Give Every Child a Chance, P.L. Carter & K.G. Welner (eds), NY: Oxford University Press.

18. Western, S. (2008). Leadership: A Critical Text. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.