The good is the enemy of the best.

—Voltaire

Another excellent example of the tenuous relationship between an idea's goodness and its success is the technology behind the World Wide Web. When Tim Berners-Lee invented the Web, he didn't have the future of technological development in mind. His tool of choice for making web sites, called HTML, reflected simple notions for what documents would be like in the future. He didn't imagine the Web would have its own economy with bookstores and banks, nor was he thinking about the billions of personal and professional web sites that would become our primary way to communicate. Instead, he thought about scientific research papers, text-heavy one-way communication, because that's what the organization he worked for worried about.

His passion for simplicity was so great that he initially downplayed the role of images and media, focusing instead on text. For his purposes, HTML was lightweight, simple, and easy to learn. Why weigh it down with the unnecessary features of other programming languages? He explicitly wanted something easier than the complex tools used for making software programs so that people could easily make web pages. In 1991, the first web server was up and running, and Berners-Lee's colleagues soon made their own web sites and web pages. [147]

In 1993, there were 130 web sites, but within six months, that number more than quadrupled. By 1995, there were over 23,000; the number would continue to double annually. [148] The simplest word processor was all anyone needed to participate, so participate they did—much to Tim Berners-Lee's and the entire world's dismay.

At the time, many computer science experts lamented how slow, un-secure, and immature the technology was behind the World Wide Web. And many still do today. They believe they know better, and that if they could go back in time and tell Berners-Lee or the folks at Netscape—makers of the first commercial web browser—what to do, all those problems would be solved (there certainly would never have been a blink tag). [149] The fallacy is that if they had their wish, they'd end up with an entirely different, and possibly not so successful, World Wide Web. Although the Web is struggling to retrofit privacy, security, and other good things, had they been in place in 1993, they may have raised barriers to entry, slowing or preventing the growth of the Internet we know today.

The factors that spread innovations, from the personal ones listed in Chapter 4 to the broader ones listed above, are largely about ease of adoption. The reason why Internet and cell phone usage climbed faster than previous technologies isn't because things happen faster today. (Nor is it because these technologies are bigger leaps forward than previous ones.) It's simply because the barriers of entry were low. People already had PCs and phone lines, making Internet use cheap and easy (economics). For cellular phones, the population already had daily experience with personal telephone usage and cordless phones, and their frequent use was accepted social behavior (culture). If you think about it, the cell phone isn't more than a cordless phone with unlimited (well, sometimes) range. The Internet and World Wide Web, for all their wonders, were an extension of the PCs and modems already in use—AOL had trained millions to use email, and word processors were popular applications on those computers.

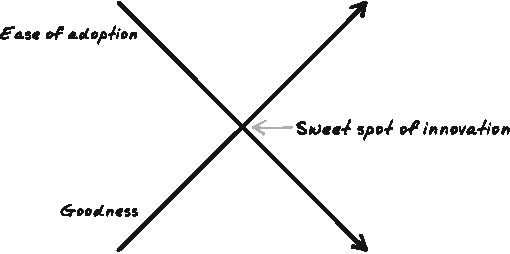

The goodness/adoption paradox surfaces if, for fun, we separate goodness (from the expert's point of view) from the factors that drive adoption (see Figure 8-2). From the expert view of goodness, better technologies existed for publishing and networking than Berners-Lee's Web. Ted Nelson and Doug Engelbart had talked about and demoed them for decades. But those "better" ideas were demanding in ways that would have raised barriers to adoption in 1991. At best, they would have cost more to build and taken more time to engineer. We can't know whether those additional barriers would have prevented the Web from succeeding or merely have changed its ascension. It's also possible these alterative web designs might have had advantages that Berners-Lee's Web didn't have, that would have positively impacted ease of adoption.

This suggests that the most successful innovations are not the most valuable or the best ideas, but the ones that appear on the sweet spot between what's good from the expert's perspective, and what can be easily adopted, given the uncertainties of all the secondary factors combined. The idealism of goodness and the notion that goodness wins is tempered by the limits and irrationalities of people's willingness to try new things, the culture of the era, and the events of the time. This explains why the first innovators—driven by the complete faith in their ideas—are so often beaten in the market, and in public perception, by latecomers willing to compromise.

[147] http://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/ShortHistory.html and http://www.w3.org/History/1989/proposal.html

[149] Even the inventor of the blink tag regrets it:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blink_tag