CHAPTER 8

STRATEGY FOR THE AGE OF NETWORKS

Companies will have to get in touch with their inner innovation networks, understand how to turn them into fluidity, and avoid becoming rigid corporate structures.

“Entropy: a vision of the ultimate, cosmic heat-death, a tonic of darkness and the final and ultimate absence of all motion.”

—Thomas Pynchon, from the short story “Entropy”1

I did not choose this quote haphazardly.

Thomas Pynchon is perhaps one of the most influential writers in American literary history, one of the greatest and darkest minds to put his thoughts in writing, and yet no one has ever seen him. Well, almost no one. It’s not uncommon for great writers to be reclusive, shying away from fans and hiding away in the comfort of anonymity. J. D. Salinger, one of the great fiction writers of the twentieth century, was a recluse. But compared to Pynchon, Salinger looks like Elton John.

Pynchon’s most celebrated novel is his third, Gravity’s Rainbow, published in 1973. It has often been compared in artistic value to James Joyce’s Ulysses. Pynchon has a gift for combining the realms of culture, history, science, and technology with the absurdity of human behavior and the preposterousness of organizational insanity. You can understand why he is one of my favorite authors.2

But he hates public exposure. After the publication and success of Gravity’s Rainbow, Pynchon was awarded the top prize at the National Book Awards ceremony in New York in 1974. A huge crowd had gathered to attend the ceremony, curious to see the by now famously reclusive author. They didn’t know that Pynchon had actually sent a comedian to accept the award on his behalf. Since no one had ever seen the author, most guests assumed that it was Pynchon on stage. Soon after, articles started to appear in newspapers stating that Pynchon was in fact a pseudonym for J. D. Salinger. Pynchon’s written response to this speculation was simple: “Not bad. Keep trying.”3

Perhaps Pynchon’s greatest literary obsession, running throughout almost all of his work, is the central theme of entropy—the ultimate “heat-death” of the universe, predicted by the merciless laws of thermodynamics. Eventually, over time, systems become affected by an ever-increasing prevalence of mediocrity, where everything becomes a constraining grayness, and eventually all motion and all life fade away.

FUN WITH CREEPING DEATH

Exactly this phenomenon seems to be affecting organizations as well. Companies seem to be battling the same homogenizing force today, moving so slowly and innovating so feebly that the ultimate end state for them seems to be “absence of all motion.” Just as Pynchon is obsessed with entropy in general, I have become besotted with the concept of entropy in organizations.

Companies seem to be obsessed, as we mere mortals often are, with longevity—constantly pondering their corporate life span, contemplating their professional shelf life, and longing to become “built to last.” But no one is. Corporate history reveals that organizations, just like us mortals, have one inevitable destiny: death.

We’ve addressed the VUCA model at length in this book, and the world of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity seems to be affecting nearly every market. It will be the playing field on which companies will need to find the fluid strategies they will need if they are to survive. In a VUCA world, the two essentials seem to be the parallel properties of speed and agility—to be fast, and to be nimble.

But is that enough? Can companies really use speed and agility to escape entropic death? And what makes organizations retain those capabilities? How can companies that grow remain capable of beating the odds of grinding to a halt?

The root cause of the entropic death of organizations is our inherent focus on the structures of organizations, rather than the intrinsic dynamics of these same organizations. We seem to revere the skeleton—the bony structures that grow but become fossilized. Instead, it is the flow of information that we should observe and cherish.

The core element enabling the survival of an organization, in my opinion, will be to rediscover the inner network—the core innovation network inside a company—and nurture that network in order to thaw the company’s frozen capabilities. Many companies have lost touch with these hidden networks, which are tucked away deep in the burrows of organizations, hidden like a reclusive author.

It does not have to be that way, though. Barclays Bank, for instance, was able, in spite of its size and age, to spot these innovation networks through an internal start-up program that was expanded after the successful launch of its person-to-person mobile payment platform Pingit in 2012. The latter was introduced in just seven months, a process that would normally have taken three years. Barclays’ program now has 40 business ideas in development.4

General Electric is a massive company with revenues of about $150 billion (£91 billion) and a market capitalization of nearly $265 billion. Yet still, it has integrated innovation into every part of its businesses. The company has thousands of researchers and engineers all over the world looking for new solutions. Its smartest move, however, was not just to depend on the intelligence within, but to experiment with open innovation. For instance, in order to respond even faster to the changes in its markets, GE invited external engineers to take part in design competitions.5 A good example is its open innovation challenge targeting opportunities to reduce greenhouse gas emissions: looking for new uses for waste heat and improved efficiency of steam generation.6

Innovation is indeed about finding and jump-starting that inner core, but it is as important to connect and collaborate with those who have the ability to look beyond a company’s limits and methods.

But the clock is still ticking for a lot of organizations. The advent of the age of networks has accelerated the rate of change of markets. And those markets are being redefined by the laws of the network, behaving differently as the lifeblood of information flow fuels the transition from markets to networks.

The core dynamic at play here is a simple rule: if the outside world starts to behave more and more like a network, you will have to start behaving like a network on the inside as well if you want to escape entropic death.

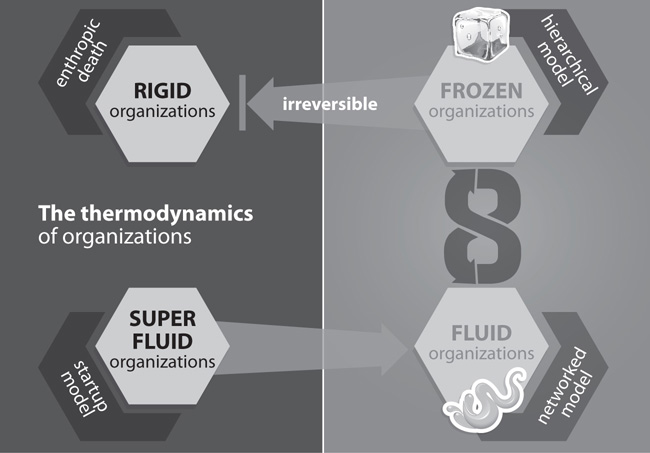

FROZEN, FLUID, RIGID, AND SUPERFLUID

This is where I believe we can originate the concept of thermodynamics of organizations. Why are some companies fluid (agile and capable of responding faster than the market), and why are some companies frozen, incapable of responding fast enough?

Let’s explore this a little further. When we talk about frozen organizations, it has a negative connotation, but it doesn’t mean that these organizations aren’t moving anymore. On the contrary, many frozen organizations are incredibly busy. They are bustling with talented people who are executing on processes, serving customers, delivering products to the markets, and trying to make their operations more smooth, more reliable, more productive, and more effective. There’s nothing wrong with that—at least, not if you’re trying to optimize your current offering and position. But if you’re trying to outsmart the competition, innovate to take advantage of new trends and opportunities, and be faster than the speed of the outside clock, you don’t want to be frozen.

Fluid organizations, on the other hand, can change quickly, not only in their offerings, but also in their form. They can shape-shift their organizations with such flexibility that they can easily adapt to market trends and changing customer behavior. Centrica-owned British Gas, for instance, the largest U.K. energy company, which has about 10 million domestic customers, sensed a disruption in its industry, with newcomers like Nest offering smart meters. Rather than continuing to optimize its services and concerning itself with “pipes and wires,” it decided on a start-up approach and introduced its very own smart-metering subsidiary, Hive. Not only did it recognize a shift in the market over time, but it bypassed its own complex and slow corporate structure with a lean start-up approach. The result was fast—and just in time—innovation, with Hive’s product development taking days and weeks rather than months and years.7

The extreme of these fluid organizations would be what I call superfluid outfits. These are so liquid, and so incredibly nimble, that they can shape-shift overnight—radically change direction on a whim. Typically you see this in the quintessential Silicon Valley start-up. With hardly any corporate structure or bureaucracy, these young firms can turn on a dime during that crucial period when they are experimenting with radically new propositions or products.

PayPal was such an organization in its early years. Its founder, Max Levchin, once confessed that he initially envisioned PayPal as a cryptography company and only later as a means of transmitting money via PDAs. After several years of experimentation and failing fast, it installed itself successfully as an online payment system that is now used by millions of people.8 The roots of Flickr lie in the development of an online role-playing game from gaming start-up Ludicorp. The founders luckily recognized the potential of simplifying photo sharing online, and their company was eventually purchased by Yahoo!9 Twitter started as a podcast delivery system; Intel sold computer memory, not microchips; Microsoft wanted to build software tools … I could go on here, but you catch my drift.

Superfluidity is actually a scientific term as well. It is one of the two states we’ve discovered so far of what we call macroscopic quantum phenomena—manifestations of the surreal world of quantum mechanics in our “normal” world. The other state is superconductivity. When a material is superconducting, you can run an electric current through it without any resistance.

This seems unearthly, but it’s one of these materializations of the strange world of quantum mechanics in our normal lives. Well, maybe not entirely normal, since you have to cool ceramic materials down to almost absolute zero in order to get superconductivity (although scientists are closing in on materials that will have this superconductive quality at room temperature, which will completely change our use of electricity and magnetism, potentially propelling us into the world of the Jetsons, with electric cars and engines that run on virtually zero energy).

FLUIDITY AND START-UPS

Start-ups are superfluid—or they should be. Unfortunately, superfluidity often comes up against the other big driving force of nature in the realm of start-ups: venture capital.

Start-ups need two things: a healthy dose of optimistic, ambitious, and talented innovators, and a heap of cash to turn those innovators’ dreams into reality. The venture capital industry and the start-up culture form a natural symbiosis. Where the two meet, amazing things can happen, and Silicon Valley is the epitome of that union of talent and money.

But the strangest thing happens when a start-up is funded by venture capital. Before that moment, when the embryonic start-up is still fueled by money from the famous trinity of friends, family, and fools, the company is superfluid to the extreme. But the moment venture capitalists put money into a company, their aim is to take a multiple of that money out. That’s their business; that’s how they survive. And that means that the venture capitalist wants the start-up to focus—to carry out the wonderful business plan on the basis of which the VC made the investment. To quit mucking about and just carry out the plan. In other words, to become less fluid. This can be extremely frustrating for the entrepreneurial founders of the company.

I have had the extreme pleasure—and luck—of founding three technology companies. The moment you launch a technology start-up, you’re looking for money: money to grow; money to hire the right talent; money to establish markets; money to expand; money to innovate. But the moment you find people with serious money to invest in your company, you are confronted with your investors’ desire that you focus, the most horrible word you can utter to a start-up. In the last company I started, the relationship between the founders and the investors deteriorated to the point where the company actually listed on the stock exchange in order to get rid of the conservative venture capitalists.

Most start-ups, as they grow and mature, naturally become less and less superfluid. But even a fluid company is amazing to observe. Fluid companies can still make sense of the signals that are coming from the market and respond to them. They can still look at technological or customer breakthroughs or trends and innovate with new offerings: new products or services. Fluid companies are capable of running faster than the market, which means that they can leverage the art of surprise. They might surprise customers with radically new offerings, shock competitors with market innovations that leave them gasping for air, or stun financial markets with colossal upsides in growth, earnings, or market share.

But when companies grow even further, they often start to freeze. When they focus intently on markets that they often dominate, they tend to emphasize the optimization of those markets rather than the innovation of new offerings. Frozen companies will look at becoming better at what they do, rather than at doing new things. They optimize operations, implement lean strategies, consolidate structures, streamline processes, and harmonize synergies. And to govern all that, they often build very elaborate structures: bureaucracies, committees, and supervising boards. A lot of consultants are hired, producing the most amazing PowerPoint presentations.

One of my favorite examples is that of Gerber’s tragic missed opportunity. In 1974, the baby food and products specialist saw its growth stagnating, so it decided to innovate. It would tackle the market of processed adult food. It seemed like an excellent idea, seeing that Americans were spending more and more time at work and had less and less time to cook. Offering quick and wholesome foods to adults would certainly open up growth.

And it probably would have worked, had the company not been so focused upon operational efficiency. Instead of developing a new line of food, it basically tried to sell its existing baby products to adults, packaged with a different label and sold in a different aisle. Needless to say, this did not work—at all. The sad part is that the original intent was a good one—anticipating a real change in food habits—but the company was so focused on its processes and its margins that it completely botched things up.10

But the danger isn’t freezing in itself, exactly. The danger is that these companies become so sluggish that they start to focus more on themselves than on the outside world. They lose touch with their customer base and become completely narcissistic and introverted, unaware of the dynamics and chatter of markets. And then they become rigid—a state of atrophy from which a company cannot escape. You may be able to turn a frozen company into a fluid one, but you can’t turn a rigid company into anything. The only fate for a rigid company is entropic death. And soon.

THE THERMODYNAMIC CYCLE OF ORGANIZATIONS

One of the fundamental notions of thermodynamics is the notion of reversibility. Some processes in nature are reversible: they can be undone, or reversed. Some processes in nature are irreversible: they cannot be undone. Turning water into ice is reversible; you can melt the ice back into water. Turning sand into glass is irreversible; you can’t turn a windshield back into a beach. The modern science of thermodynamics is actually quite recent, but it deals with fundamental processes that humans have observed in nature since their very existence: the transition of ice into water, water into vapor, and back. Of course, these processes depend on external factors such as temperature and pressure. Water boils at 100 degrees Celsius, at least at sea level, in most of the world (except in the United States, where it boils at 212 degrees Fahrenheit). But water will boil at only 80 degrees Celsius at the top of Mount Everest. The laws of thermodynamics govern the way the same chemical, H2O, materializes into frozen ice, liquid water and nebulous vapor, under the conditions of heat and pressure.

Thermodynamics is very tangible and very practical. It has given rise to a ton of pragmatic applications that have made our lives better, including the air-conditioning systems that keep our bodies cool and the cycles of compression and expansion of Freon gas inside our refrigerators that keep our food cool.

I believe the time is right to apply the simple concept of thermodynamic cycles to the world of business organizations. I believe the fundamental transition of organizations from superfluid to fluid to frozen and (irreversibly) to rigid can be understood through a very simple organizational thermodynamic chart.

The companies that are capable of escaping entropic death will be those that can cycle between fluid and frozen states, like General Electric, Google, or Eli Lilly. Frozen isn’t always bad. In fact, parts of an organization—perhaps even most of it—can be locked in to focus on a market mechanism that the organization understands really well. If core processes are optimized, this frozen mechanism can generate an amazing amount of profit and wealth. But if the organization lacks sufficient innovation liquidity, chances are that it will slowly and irreversibly become rigid. Like Blockbuster, which failed to react appropriately to the entrance of the likes of Netflix in its market. Like Kodak, which failed to recognize the disruptive power of digital photography. Or like Borders, which made the tragic mistake of underestimating what the Internet would mean for bookselling. The challenge for companies is to keep parts of the organization, parts of its skill base, in a fluid state, allowing room for experimentation, room for understanding the agility of the markets, and room to innovate fast enough to outsmart the market.

But how can a company create a dual state of frozen and fluid? How can a company be flexible enough to escape the irreversible entropic death trap of rigidity? For the answers, we will have to take a closer look at the brain.

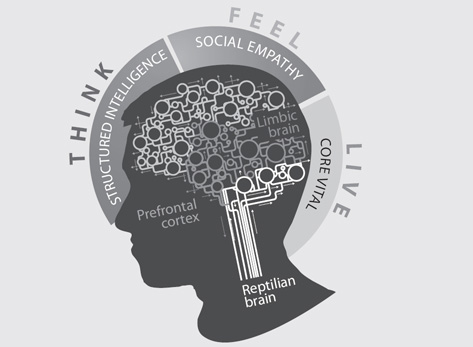

THE TRIUNE BRAIN

It seems that nowadays no book or lecture is complete without a pseudo scientific exploration of the human brain in there somewhere. Oh, and it should include at least one visual diagram of the brain, pointing out the neocortex and perhaps some more exotic parts.

Actually, brain structure is extremely relevant to the discussion of fluid and frozen organizations.

The triune brain is a model proposed by the American physician and neuroscientist Paul D. MacLean. In his model, our brain consists of the reptilian complex, the limbic system (the paleomammalian complex), and the neocortex, also known as the neomammalian complex.11

Reduced to its essence, the reptilian brain keeps us alive. It’s the core engine of survival.

The limbic system keeps us coherent as a species. The way we interact, survive in groups, and feel empathy are all part of the limbic system. It’s the social side of the brain.

The third component, the neocortex, is the part that we’re so proud of as human beings. Our capacity for logical thought, structured analysis, and the deep understanding of how pivot tables work in Microsoft Excel is all thanks to the marvels of the neocortex. It is the pinnacle of human evolution, and it’s also slow. Incredibly slow.

The reptilian brain processes millions of bits of information per second, every second—all the inputs signaling motion, temperature, pressure, and other forces coming from the myriad sensors of your body. But you don’t even notice it.

By contrast, the famous neocortex is slow as hell. This section can process only a handful of information. Some researchers claim that our illustrious neocortex can process less than 100 bits of information per second. In the same second, the reptilian brain has processed millions of bits. In terms of raw power, the reptilian brain blows the neocortex away. But the reptilian brain can’t do pivot tables, so the neocortex gets all the publicity.

The neocortex is your conscious brain. This is the part that can think about itself and reflect on the conscious will that you have, the full control over your ideas, personality, behavior, and actions.

But recently, many researchers have started to raise big question marks about free will. A tremendous amount of research has gone into the way we perceive choice. As we saw in our discussion on the evolution from markets to networks, the field of neuromarketing relies heavily on being able to influence our subconscious.

Let’s face it: our conscious brain is probably overrated. If I throw a baseball at you, at high speed and without prior warning, chances are that you’ll be able to catch the ball (or at least duck) before it strikes you in the face. Hopefully. But you didn’t have time to think it over, or to weigh your options. Your response was processed by the reptile within—not by the vaunted conscious part of your brain.

And your conscious brain hates that. There’s nothing it despises more than the idea that it doesn’t have everything under absolute control. So it makes up a story that it caught the ball on purpose, by sheer force of logic and reasoning. But that’s a lie. Recent neurostudies have shown that the logical and structured part of our brain is constantly making up stories to assure itself that everything is under control. But in reality, many of our actions and behavior are completely out of the scope of our free will, and are instead driven by our unconscious.

The theory of the triune brain has been contested by many researchers, who claim that it is too simplistic. But I like the simplicity of there being three big factors that make up the workings of our gray matter—survival, social, and logical—and I think this theory works very well as a model for understanding our behavior.

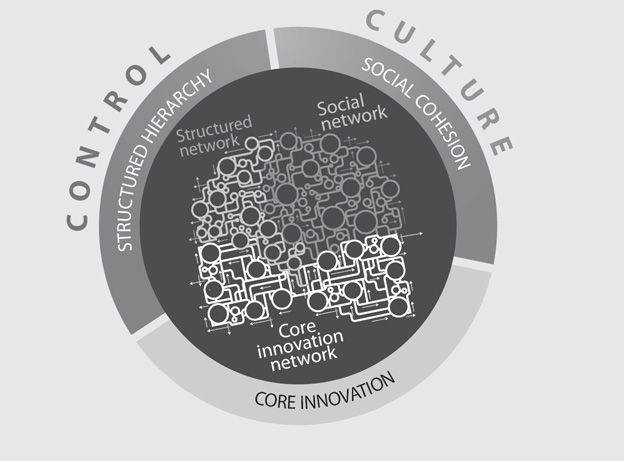

THE TRIUNE NETWORKS

Just as our gray matter is made up of three parts, I think our organizations have three distinct internal networks that together form the triune networks of companies:

1. The core innovation network

2. The social network

3. The structured network, or hierarchy

The core innovation network is the essential network of people that make innovation happen at your organization. When a company is small, this core survival network is clearly visible, but as a company grows, it becomes reclusive and is no longer clearly visible. But it is vital. It is the core group of people that you would need if you ever had to start over.

It’s the nucleus that could go across the street and start a competitor to your business. It’s the group that might find the next idea to take your business to a new level—and the group of people you’d be most horrified to see your competitors get hold of. But most companies have lost sight of who participates in their core innovation network. It’s like a secret society buried deep in the dungeons of the corporate hierarchy.

A company is also a social network—a group of people who work together, relate to one another, and spend a lot of time with one another. Companies are filled with people who become friends (or enemies, for that matter) and develop relationships and ties. These social networks are crucial in developing or changing a company’s culture, and they have become vital in understanding why people want to belong to a group or engage with an organization. In the very same way that customers relate to the image of a product, these cultural networks inside companies are vital conduits for the emotional sentiment that runs through an organization. It’s no wonder that the companies that attract the smartest and most talented people—like Google, SAS, or salesforce.com—invest a lot in keeping their personnel happy, inducing a tight community feeling, and having their staff function like a “tribe.”

The final part of the triune network tends to be the most visible: the hierarchical network, often depicted in the infamous org chart. This network determines who does what and who reports to whom. The hierarchical network has a huge role to play in a company, especially in areas where a military command-and-control structure is needed to maximize operational efficiency. Unfortunately, this third network is often the only one that really captures the attention of top management.

WHY START-UPS ARE MAGIC

As I’ve mentioned before, I’ve had the enormous privilege and pleasure of being involved in three technology start-ups, early on in life.

Few activities are more intoxicating than doing a start-up venture. With a small group of like-minded enthusiasts, you’re out to break the rules and cross frontiers. You’re out to change the world.

All three of those start-ups were exhilarating and fascinating. But each one was also an enormous risk, a huge effort, and a tremendous fight. None of them was easy.

One of the things I’ve observed in these start-ups, and in many other start-up activities I’ve observed, is that when you start out, the three networks we just discussed are completely in sync. As a matter of fact, they’re indistinguishable. The triune networks sync completely.

Your core innovation network is your start-up; these are the people that you believe can change the world, the ones who are willing to take huge personal risks and are excited about the thrill of being part of something magical. But they’re often also your social network. Very often, the people you hire at the beginning of a start-up are your friends, the people you met in your dorm, friends of friends, or the people you’re comfortable with. And since in a start-up, you spend pretty much all your waking hours on your project, you’re likely to have no other friends.

But the start-up is also the structured network, the hierarchy. People who believe that there is no hierarchy in a start-up have obviously never really experienced a start-up. Hierarchies in a start-up are fierce, clear, and unambiguous. They’re undocumented, but they’re fully understood. Everyone in the start-up knows exactly who calls the shots and who gets the credit. All the developers know who’s the top coder, who controls the architecture, and who decides what to build. All the salespeople know who the top dogs are; the market guys know who makes the calls.

The structured network is the same as the social network is the same as the core innovation network. The three networks map perfectly. As a start-up grows and matures, however, the three networks tend to grow apart. They become less intertwined, sometimes separating entirely.

The most magical moment in the life of any start-up is when, for whatever reason, you post your first org chart. It could be that you’ve just landed a big round of financing or venture capital funding, and the venture capitalist on your board would like to understand how this joint is organized: who’s in charge, and who reports to whom.

When the first org chart is posted on the wall, it can be a hilarious moment. ‘Really? George is the lead architect reporting to the CTO?’ Everyone in the company knows that George doesn’t know shit about architecture! The guy who really knows the ins and outs of the product architecture is José, who lives in the basement. Literally. He bunks out on an inflatable mattress next to the development servers, eating pizza by the blinking lights of his machines. José built the architecture, lives the architecture, is the architecture. But you can’t show José to investors. He probably doesn’t even own a suit or a pair of presentable shoes. In contrast, George wears an Italian suit and shiny wingtips—and he can draw really cool diagrams in PowerPoint that are very convincing at board meetings.

So George is the lead architect. George is happy—he’s on the org chart. But José is happy, too. He’s happy sleeping with his servers and building the next level of the product’s architecture. He’s also very happy that he doesn’t have to present or report to the board, because the idea of that terrifies him, and he’d probably have to buy a suit, which he hates. George is happy. José is happy. The board members are happy. Everyone is happy.

But as the start-up grows, it loses touch with its innovation network. George is promoted. He rises through the ranks as more and more prestigious jobs appear on the org chart that require the essential skills of devising beautiful PowerPoint slides and uttering meaningful sentences about flexible design strategy and modular scalable components, while wearing impeccable suits. Eventually, George becomes CTO.

But unlike in the beginning, when everyone knew that José was the real genius behind the product’s architecture and the core innovator in the organization, now few people have any clue what that weirdo with the beard and the flip-flops and the “Yoda Lives Forever” T-shirt actually does down there in the basement. José never made it into the structured network. He dropped off the social network pretty quickly as well. But José is still a pivotal node in the core innovation network of the company.

And he’s the first person I’d hire if I wanted to start a new start-up that would blow the old company out of the water.

INDUSTRY DISRUPTION

Start-ups are a petri dish on steroids when it comes to organizational evolution. The transition from an idea on the back of a cocktail napkin to a superfluid organization is sheer magic. But it happens every day. There are more than 25,000 start-ups in the San Francisco and Silicon Valley area, all aiming to blow the previous generation of miracle tech companies out of the water. All aiming to become the next Google, Facebook, or Twitter.

Mark Zawacki is based in Palo Alto, at the epicenter of entrepreneurial disruption. Mark runs a company called 650 Labs, whose name is based on the telephone area code for Silicon Valley. He’s a strategy consultant and angel investor who spends a great deal of his time helping traditional companies understand the magic of entrepreneurial innovation that is the hallmark of Silicon Valley—and helping them rub some of that magic onto their own organizations.

According to Mark, the biggest shift of the last couple of years is that Silicon Valley is moving from being the high-tech capital of the world to becoming the industry-disruption capital of the world. We all know that Silicon Valley gave birth to technology giants such as Hewlett-Packard, Intel, Cisco, Sun Microsystems, and Oracle. These companies all grew up in the intoxicating entrepreneurial landscape of Silicon Valley, where such tech giants could flourish. But that is exactly what they were: technology companies. According to Zawacki, today, the Valley and San Francisco are filled with start-ups that use technology; they employ the same technology geniuses from Stanford and MIT, but they are out to completely disrupt other industries.

Facebook is not a technology company, but it has completely redrawn the business model of advertising for the age of networks (University Avenue in Palo Alto has replaced Madison Avenue in New York as the epicenter of advertising innovation). Netflix is not a technology company, but it is redefining the foundations of the media industry, as well as the model of the television industry. Tesla is not a technology company, but it is completely disrupting the age-old model of the car industry. I could go on and on with many of the area’s 25,000 start-ups.

When you look up synonyms for organization, you get equivalents such as firm, corporation, and institution. Those words say a lot. Firm connotes something fixed, solid, and unyielding. And I shudder whenever I hear the word corporation, which suggests something stringent, bureaucratic, and inflexible. The shadow of entropic death flutters nearby.

And when you then see the rate of innovation that these new innovative start-ups are bringing, and how much disruption they can bring to age-old industries, you can begin to understand what keeps companies from being swallowed by that shadow. Companies will have to get in touch with their inner innovation networks, understand how to turn them into fluidity, and avoid becoming rigid corporate structures that will get run over like deer staring frozenly into the headlights of the oncoming cars.

IT TAKES A NETWORK TO FIGHT A NETWORK

U.S. Army General Stanley McChrystal has had a long military relationship with the Middle East. He saw action in operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm, was the commanding general in Afghanistan in 2009 and 2010, and before that was the commander of the Joint Special Operations Command from 2003 until 2008. In 2010, McChrystal was forced to resign from his post after Rolling Stone magazine published an article called “The Runaway General.” The politicians back home did not appreciate the candor, frankness, and criticism expressed in the article. The general had to take the fall.12

Today, Stanley McChrystal is helping companies understand why networks are important, and why old structures don’t work any longer. To do so, he founded a consulting firm called McChrystal Group.

The heart of his philosophy is based on the things he learned while fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, and his failure when he tried to use old military structures in a war on terrorism, where his adversary was not a structure, but a network.

The U.S. military was used to fighting structures similar to its own. Wars were mostly waged between centralized, hierarchical structures with military-style control, command, and discipline. That approach worked well in the two world wars and even during the cold war. But it failed in fighting enemies such as terrorist networks.

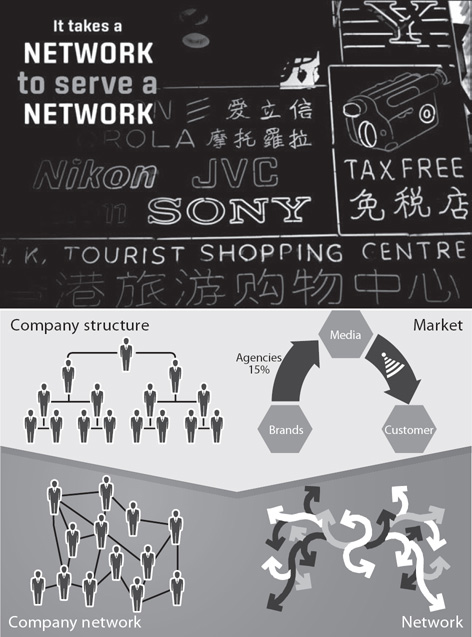

McChrystal learned this the hard way. In his own words, “In bitter, bloody fights in both Afghanistan and Iraq, it became clear to me and to many others that to defeat a networked enemy we had to become a network ourselves.”

This became the central theme of his doctrine: “It takes a network to defeat a network.”

As McChrystal describes it, in Iraq, Al-Qaeda operatives did not wait for memos from their superiors, much less direct orders from bin Laden. Decisions were not centralized, but were made quickly and communicated laterally across the organization. He portrayed the fight with his enemy as a deadly dance with a constantly changing, often unrecognizable structure.

McChrystal tried to turn his old-style military structure into a network to match the workings of his enemy: “We had to figure out a way to retain our traditional capabilities of professionalism and technology, while achieving levels of knowledge, speed, precision, and unity of effort that only a network could provide.”

The Rolling Stone article came too soon. McChrystal’s resignation cost him the opportunity to try to transform U.S. military operations into full-fledged networks that would be better suited to this new kind of enemy. He may not be the first military commander in history to clearly see the strategic need to transform, but he’s the first to define that need so clearly for the present age.

THE GOLDEN RULE

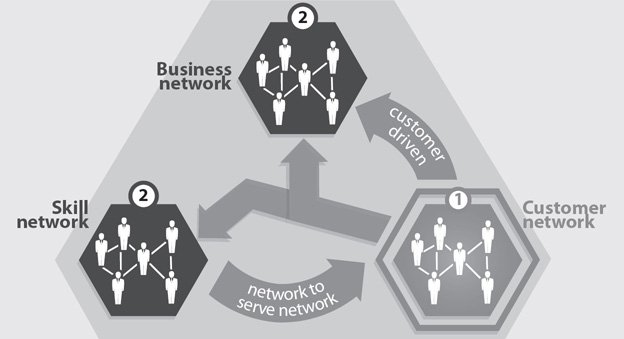

As we described earlier, the fundamental shift that we are now seeing is that markets are becoming networks. Customers form the heart of networks of intelligence, and old marketing concepts don’t work any longer. We have to learn how to connect to consumers, influence networks of information, and understand the dynamics of network behavior.

These imperatives also have huge consequences for the way we see the evolution of organizations. The core dynamic at play here is a simple rule: as the outside world starts to behave more and more like a network, the inside of your company will have to start behaving like a network.

I believe that this is the single biggest challenge facing corporations today. When I wrote The New Normal, I was convinced that the rise of digital, and the fact that technology was rapidly becoming normal, was a wake-up call for companies, alerting them to a need to pay attention to an age in which they would have to communicate with customers in a different way as a result of the abundance of digital communications.

But now I think that digital was only the appetizer. The New Normal is just the foundation for the age of networks, a much more fundamental transition in business strategic thinking, in which companies will be confronted with the interplay of network behavior throughout their businesses, markets and workforce.

THE HOLY TRINITY IN THE AGE OF NETWORKS

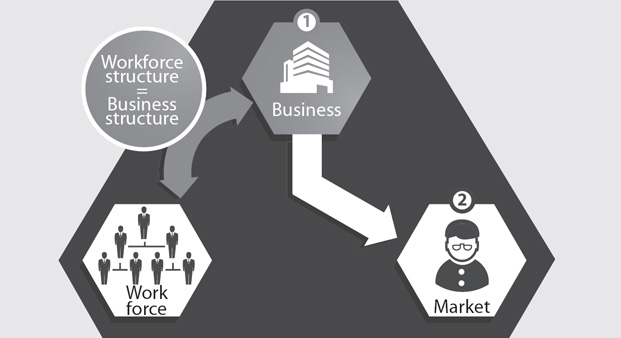

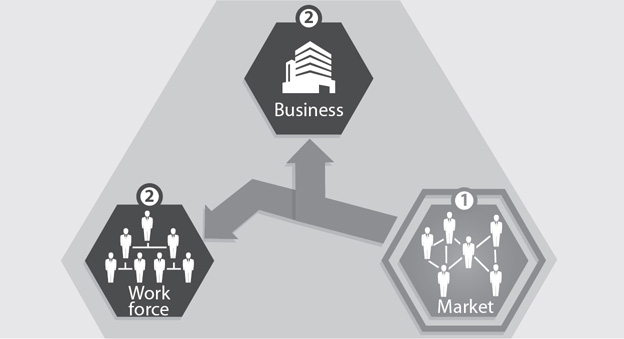

In the world of business, the holy trinity is the combination of a company’s business strategy (B), the company’s market (M), and the company’s workforce (W). The correlation among these BMW elements defines the way a company operates, grows, and evolves.

In the Old Normal, a company typically drove its business strategy forward with an inside-out approach. It would devise a strategy for conquering or cornering a market, deduce what kind of offering it would need in order to make that happen, and then project that offering onto the market, figuring out what kinds of customer segments to target with its offering. The structure that was applied to the workforce often mirrored the business structure of the organization. Employees would be drafted into departments and silos that imitated the business units and departments of the company.

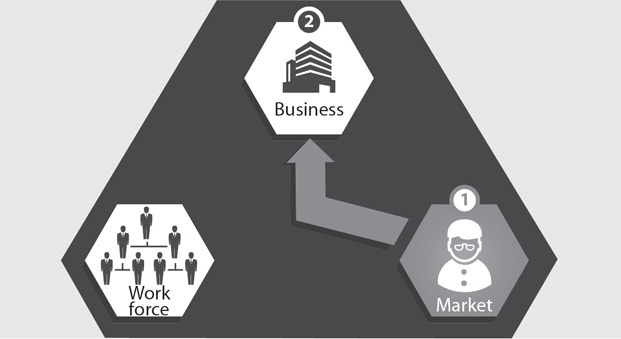

With the advent of the age of networks, that model fundamentally changes. As the consumer becomes more connected and empowered than ever before, it flips. When markets become networks, companies will have to understand how to tailor their business for these newly empowered customers—and learn to mirror the form that empowers them: the network.

This will have a profound impact on the way we organize our workforce as well. When the golden rule of “It takes a network to serve a network” is applied, this means that our old bureaucratic structures will no longer suffice. These structures won’t be dismantled entirely, since they will still function in frozen parts of the organization. But in those areas where markets are heating up and becoming networks, the frozen organizational structures of the past are no longer valid. In these networks, where fluidity is the norm, organizations that are hoping to innovate will have to become networks as well.

The full picture becomes visible when we attempt to label these transitions. Markets are turning into networks of information, serving customer networks. The workforce of an organization has to understand the implications and limitations of the structured hierarchies, and adopt the notion of skills networks in order to survive. And eventually, network-based thinking will allow a company to dramatically rethink its role, decompose its core offering, and work differently with partners and suppliers, eventually becoming a business network itself.

Companies are no longer smart enough, fast enough, or innovative enough to survive on their own. And a lot of larger corporations have started to understand the value of networked collaboration. It’s like Toyota Motor Corp. partnering with Microsoft to develop a software platform for managing the information systems of electric vehicles. Or like the Coca-Cola Company working with Heinz to produce a bottle made of 100 percent plant-derived material. Or American Express partnering with Foursquare to offer location-based discounts from participating merchants.13 Or AstraZeneca offering easy access to its library of clinical compounds on a collaboration platform to facilitate research.14

Philips even has numerous collaborations with companies from different industries. It has, for instance, innovated together with Nivea on a conditioner-dispensing shaver, with BASF on a solar car roof, and with Aerogen on a noninvasive ventilation system for patients with breathing problems.

Another great example is that of the Solar Impulse partner team of—among others—Omega, Schindler, and Deutsche Bank that came together in 2004 and is led by Solvay. Together they built the very first aircraft in history to fly both day and night without using fossil fuels.15

WAVES OF DISRUPTION

In the coming years, with the full force of VUCA hitting the world of business, we will see waves of enterprise business model disruption that reshape entire markets and market systems. When the laws of networks behavior overturn our understanding of market dynamics, we will see that the companies that survive will be those that have understood the need to drastically rethink their organizational fabric.

Whenever radical shifts of theory occur, whether in science, culture, or philosophy, the prevailing inclination is to discredit this new way of thinking, precisely because it is so radically different from the past. That has caused great frustration for the creative thinkers behind the novel ideas. Take Ludwig Boltzmann, one of the greatest scientists to come out of Austria. Born in 1844, he was a physicist and philosopher who was one of the key thinkers in the radically new field of thermodynamics.

Boltzmann was a genius, succeeding his teacher Joseph Stefan as professor of theoretical physics at the University of Vienna, where he taught physics and lectured on philosophy. Boltzmann was a great teacher, whose lectures on natural philosophy received a considerable amount of attention. His first lecture was so successful that, although the largest lecture hall at the university had been chosen for it, people had to stand all the way down the staircase. Word of his genius led the emperor of Austria to invite him for a session at the palace.

Boltzmann’s peers in the field of science were not so enthusiastic, however. He was one of the key architects of the famous second law of thermodynamics, the entropy law, contributing insights from his background in statistical mechanics. His ideas were a radical departure from the prevailing scientific ideas at the time, and his critics were fierce in their attacks.

In fact, Boltzmann decided to become a philosopher in order to refute the philosophical objections to his physics. But he soon became discouraged by the ongoing criticism of his peers. On September 5, 1906, while on a summer vacation with his wife and daughter in Duino, near Trieste, Boltzmann hanged himself during an attack of depression. He was buried in the Viennese Zentralfriedhof, and his tombstone bears the inscription

S = k · log W

where S is a representation for the concept of entropy.

THE AGE OF NETWORKS

More than one hundred years after Boltzmann’s death, the concept of entropy continues to fascinate mankind.

We have come to clearly understand the role that entropy plays in science, but I believe that entropy also plays a huge role in the way we have developed organizations and looked at markets. When companies grow, their internal capacity to innovate, and therefore survive, seems to diminish. Many large corporations seem to be heading for entropic death.

When markets become networks, new laws are at play. New theories will have to be developed, new concepts to be explored. Again, business can learn a lot from how science has looked at these new varieties of systems. Ilya Prigogine was the founder of the science of self-organizing systems. He was able to link his work in chemistry to the domains of biology and sociology. His work is seen by many as a bridge between natural sciences and social sciences. It is just those kinds of bridges that can be most helpful when adapting to a radically new reality.

Today we are about to see similar concepts in the world of business. When markets become networks, companies will have to become networks—and, in particular, scale-free networks. Unlike top-down hierarchies, these scale-free networks emerge from bottom-up interactions, and appear to be limitless in size.

In the age of networks, we have to understand that there is more to running a company than a top-down bureaucracy. In the age of networks, we have to understand the thermodynamics of organizations.