CHAPTER 1

THE AGE OF UNCERTAINTY

Building a culture of experimentation means implementing an attitude toward risk that will be necessary if we are to survive in a world in which strategy becomes fluid.

We would love to build a model that describes everything about our markets, customers, and organizations, and use that model to build the perfect strategy for the future. Unfortunately, that doesn’t work, and it never will. The future is characterized by VUCA: volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. Therefore, no model will ever suffice. Instead, we have to focus on building agility, acting fast, and nurturing creative thinking by stimulating our companies’ networks and adopting a culture of experimentation.

The Holy Grail for many companies is to build the “ultimate knowledge tool.” This is a mythical spreadsheet that companies hope to use in order to build an all-encompassing model of their enterprise. They could feed into it all the inputs of their business, insights into the behavior of their customers, and all the relevant knowledge about trends in their markets. From this ultimate shiny model, they would be able to deduce the perfect strategy.

Nobody has yet built such a spreadsheet. No one has found the Holy Grail, either, but that doesn’t mean that people aren’t still looking for it after two thousand years. In the same way, companies seem to be constantly in search of the perfect strategy.

In fact, strategy is the number one category in the extremely lucrative management book market. Innovation is number two, because people quickly realize that they have to come up with something that is truly unique if they are to survive. Third on the bestseller list is self-help guides, written to help the disenchanted crowd of depressed businesspeople who have learned that there is no ultimate strategy and no magic recipe for innovation.

THE THEORY OF EVERYTHING

We humans seem to be obsessed with modeling. It’s our way of figuring out how things really work, and our attempt to do that by using formulas, concepts, and mechanisms. The history of physics is thousands of years of trying to figure out the elusive “theory of everything” to explain it all.

Physics is still trying to figure it out, and every time the physicists think they have it nailed, they find that they have to dig deeper and build more models, like the Russian matryoshka nesting dolls. Newtonian physics worked like a charm, explaining everything from the movement of planets to the falling of apples. It seemed to be pretty much perfect—that is, until it was applied to things that were very small. For that, we needed quantum mechanics. Or how about for things that go very fast, such as light? For that, we invented the theory of relativity. Every time we dig a little deeper into physics, we understand a bit more about how the universe actually works, and we adapt our “model” accordingly.

Physicians have been trying to understand our bodies and the complex workings of our brains for centuries. And it’s true that the medical profession now knows a considerable amount more than it did in the days of bloodletting and lobotomies. But we are still light-years away from being able to model the human brain. Yet we humans are a persistent bunch. We won’t stop until we’ve built that ultimate model of our gray matter.

In business, we also try to model everything. For years, economists have been trying to model markets, companies, processes … anything, really. They’ve been trying to create models that would explain market behaviors and models that would even explain the weather. They’ve even tried to create a “magnum model” of models.

THE RAND CORPORATION

One company that has always fascinated me is the RAND Corporation. This secretive organization, based in Santa Monica, California, was formed in the wake of World War II by the U.S. Department of Defense, the Air Force in particular. The Air Force viewed itself as being much more sophisticated than the Army, from which it had been spun off. The Army had troops and tanks, while the Air Force had all kinds of cool stuff, from planes to nuclear technology. In order to maintain that edge—and to maintain control of nuclear strategy—the Air Force needed a research arm. That’s why the RAND Corporation was created.

The RAND Corporation (short for research and development) was set up in 1946. Its primary goal was to help the U.S. Air Force define a strategy for the long-term planning of future weapons. In other words, during the cold war, it would plan for nuclear war.1

Like the Manhattan Project before it, RAND recruited the smartest people on the planet, including more than 30 Nobel Prize winners. Since its inception, RAND has drawn upon top scientists, mathematicians, and physicists who believed in the ultimate model—and in the ultimate chance to use mathematics to shape the universe and the future.

The charged atmosphere at the RAND Corporation during the fifties must have been exhilarating and intoxicating, with the sharpest minds of the “free world” working to figure out how to remain free—and win a nuclear war.

One of the most colorful and influential figures in the RAND Corporation was a man named Herman Kahn. Stanley Kubrick immortalized him as “Dr. Strangelove” in 1964.

Herman Kahn was born in New Jersey, the son of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. He was raised in Los Angeles and attended UCLA, where he got a degree in physics. He was working on a PhD at Caltech, but he had to drop out for financial reasons (not for lack of talent). Rumors were that he had the highest IQ ever measured. Kahn became friends with Samuel Cohen, the inventor of the neutron bomb, who introduced him to the RAND Corporation. He was recruited soon afterward, in 1947. Kahn took to RAND like a duck to water.

He quickly became a major player at RAND, with a unique style. A master showman, he would deliver 12-hour lectures spread over two days, using huge sets of charts and slides.

For more than 10 years, Kahn developed a novel technique known as systems analysis. The idea was to build the most perfect model of a strategic question by first analyzing and then synthesizing a model that could be used to run different scenarios. The verbs analyze and synthesize have Greek origins, where they mean, respectively, “to take apart” and “to put together.” That’s exactly what Kahn wanted to do for nuclear strategy. The result would be a model of the cold war that could define not only what the endgame with the Russians would be, but also how much it would cost. 2

To Kahn, it was like playing a giant game of Risk. But given the mighty computers that he had at his disposal and the enormous impact that his models had on real nuclear strategy, this game was frightfully real. By putting into his models the quantities of bombers and radar systems, and the location of airfields and missiles, Kahn could calculate how many civilian deaths would result from various nuclear scenarios. He could determine how many cities would be wiped out and how much collateral damage there would be. Kahn’s model of the cold war directly influenced how many billions of dollars were allocated to the U.S. Department of Defense. But he was also calculating just how many hundreds of millions of people would perish in the event of a full-blown nuclear war.

He finally published his magnum opus, called On Thermonuclear War, in 1960, the title being a reference to the classic nineteenth-century work by Carl von Clausewitz, On War. His boss thought Kahn had gone too far, and told him that the work “should be burned.” However, the book provided amazing insights into the model that the RAND Corporation had built. In the first three months, On Thermonuclear War sold more than 14,000 copies, and it was read with great interest on both sides of the Iron Curtain. The Soviet newspaper Pravda trashed the book, calling RAND the “academy of science and death.” However, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was a great admirer of the book, and of Kahn.3

The amazing thing about the model that Kahn built was that it described a post-nuclear war world—a world in which, depending on the variables, hundreds of millions had died or “merely” a few major cities had been destroyed. Kahn argued that life would go on, and that the “survivors would not envy the dead.” Just as Europe had managed to continue after the devastatingly deadly effects of the Black Death in the fourteenth century, Kahn believed that people would cope, and that humanity would prevail.

Understandably, Kahn’s theory was highly controversial. Not only did he use his model to think about the world after a nuclear war, but he was also incredibly provocative in his solutions for coping in a post-nuclear holocaust era. For example, he suggested grading food based on the amount of radioactive contamination it contained. The most highly radioactive food should be consumed primarily by the elderly, who would probably die before the delayed onset of cancers caused by radioactivity. Kahn was a nuclear provocateur. But he was a scientist first, and in the fifties it was very plausible that there would be a nuclear arm-wrestling match between the United States and Russia.

As Kahn put it, he was “trying to design a system capable of meeting contingencies which will arise five to fifteen years into the future.” To put it differently, the RAND Corporation was trying to predict how the world would evolve—exactly what every company that is chasing that Holy Grail of the “Ultimate Excel” is trying to do.

THE ULTIMATE MODEL

Kahn took advantage of the rise of digital computers, which were building up enough horsepower to be able to do those calculations, to run all those simulations, and, ultimately, to take the human side out of the equation. Certainly, in the context of predicting the outcome of nuclear war, with possibly hundreds of millions of civilians dying, the human factor in decision making was often disturbing. As Kahn put it, “under these circumstances, competent, honest people often don’t do very well.”

And here we come to the heart of the matter. We seem to be set on building the ultimate model—one that will guide us to the ultimate strategy and eliminate the human element in decision making.

Kahn believed that if computers got better, if technology got stronger, then he could build better and better models and get closer to that Holy Grail of the ultimate model. Indeed, during this period, the capabilities of computer systems were advancing by leaps and bounds. Kahn observed an “exponential increase in the state of the art of [computer] technology in the past twenty years.” Little did he know that this was only the beginning of the exponential curve of technology dictated by Moore’s Law.4

Kahn also understood that the technologists who were working on these new computer systems had a habit of overestimating their ability to apply new ideas in the immediate future, and underestimating the impact of their technology on the long term.

STEPPING INTO THE UNKNOWN

After a falling-out with the RAND Corporation in 1960, Kahn left and founded the Hudson Institute, then located in Croton-on-Hudson, New York. In his words, the Hudson Institute was to be a “high-class RAND.” In 1967, Kahn produced a fascinating report from the Hudson Institute, called The Year 2000: A Framework for Speculation on the Next Thirty-Three Years. In it, he described 100 technical innovations that were very likely to happen. Among them were:

74. Pervasive business of computers

81. Personal pagers (perhaps even pocket phones)

84. Home computers to run households and communicate with the outside world5

If you thought that Bill Gates or Steve Jobs invented home computers, or that it took until the World Wide Web to envision something like the Internet, think again. Kahn had amazing insight, even predicting, as item 67, the “commercial extraction of oil from shale.” He was a bona fide genius, disliked by many for the controversies he created, but a true pioneer of models. He passed away in 1983, at the age of 61.

But Herman Kahn also saw the limitations of models—that they could get you only so far. He was a great student of the history of war, and he was fascinated by the mistakes the French made in dealing with Germany in World War II. In his words: “The French had more and better tanks than the Germans, about as many planes, and given their fortification systems, seemingly as good an army. The Germans were just better in the imponderables.” An imponderable, as the dictionary defines it, is “that which is difficult or impossible to assess”—in other words, the unknown. As Kahn describes it, by conventional measures, the Germans would have had no chance against the French at the advent of World War II, but the Germans avoided a direct assault on the famous Maginot Line of French defense by violating the neutrality of Belgium and penetrating France from that direction on May 10, 1940. By June 22, they had invaded most of France, and the French surrendered. The invasion was not planned by any model, but by making clever use of an imponderable. Certainly the French never thought of that possibility.

Kahn realized that in the end, models are only models, and you can’t predict every imponderable, no matter how much computing power you have. He actually told the U.S. Department of Defense that “the most important thing to do is to see that we maintain a great deal of flexibility in our military capability, and have available many options in order to meet a variety of contingencies.” In other words: prepare for the unknown by keeping as many options open as possible. So much for those powerful models.

If you look at military strategy after the cold war, which was still being devised by the great military think tanks like the RAND Corporation, the planners started to take these imponderables very seriously. Actually, they now pretty much depend completely on understanding the world of the imponderables.

Today, the concept of imponderables is at the heart of military thinking. Strategists realize that the world can change instantly. The end of the cold war came like a bolt out of the blue. And no Kahn model could have ever predicted the events of 9/11. As a result, current military strategy is now based on the concept of VUCA.6

VUCA

Let’s explore what the acronym VUCA means to corporations.

V stands for volatility. The word volatility comes from the Latin verb volare, which means “to fly.” It basically means that things tend to vary often and widely. In today’s world, things are changing faster and faster, and stability often seems unattainable. After the financial crisis and the economic turmoil of the past few years, many people have been wondering, “When will things get back to being stable again?” The answer could be never. Perhaps we’re living in times of greater and greater instability, more and more turbulence, and increasing volatility. Stability is flying away.

U stands for uncertainty. Many of us grew up trying to build a world based on security—things that we could count on, bank on, and build on. Now, more and more, we seem to be surrounded by uncertainties. We’re uncertain about where the economy is heading. We’re uncertain about where technology is heading. We’re uncertain about whether our companies will survive, how our customers will react, and how our markets will evolve. We seem to be heading toward a world in which we have more uncertainties than certainties to deal with.

C stands for complexity. The world has become incredibly complex, and little things can have a huge effect. Scientists have been studying this dynamic, in a field that is often labeled chaos theory, for years. It’s often characterized by the notion of the butterfly effect, a term coined by meteorologist Edward Lorenz back in 1963. Lorenz was trying to predict the weather by building complex mathematical models of weather systems. (You could say that he was the Herman Kahn of weather forecasting.) He observed that although the computers that ran his models were getting better and faster, and his models were getting better and more complex, his ability to predict the weather wasn’t improving much. He observed chaotic behavior in his weather systems, in which tiny differences in a system could trigger vast and unexpected results. In a 1972 paper, he described this by saying that a flap of a “butterfly’s wings in Brazil could set off a tornado in Texas.” Today we see more and more of these chaos-theory effects in a world of ever-increasing complexity.

A stands for ambiguity. Ambiguity means that you can interpret things in more than one way—that things depend on their context, and that you have to interpret the whole picture in order to understand something. Ambiguous is not the same as vague. It means that things are not always black or white, one or zero. Too bad for all the digital zealots, but the world can’t always be boxed in. Ambiguity means that questions don’t always have a single “straight answer.”

But what does VUCA mean for corporations? What does it mean for companies with armies of workers laboring in structures built on the notion of long-term thinking? Or for those who have built strategies on the basis of consumer models, market models, and growth models based in Kahn-like reasoning?

The result is that in the VUCA world of today, business strategies have become more fluid. The traditional five-year plan makes no sense to companies whose world is changing faster and faster. What use is a five-year strategy for the newspaper industry, which is watching its markets disappear at the hands of Twitter and Craigslist? What use is a five-year strategy for the television industry, which is seeing its markets flip completely because of YouTube, Netflix, and Hulu?

The reality is that companies now update their strategies more frequently than ever before. They have to, if they want to survive. I heard one CEO tell me, “We still have a five-year strategy. Actually I have a new one every three months.”

This is the era of “fluid strategy,” and it means that companies have to act more quickly—and be more agile—than ever before.

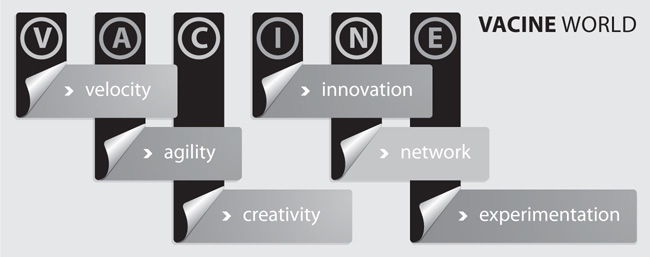

VACINE

As a matter of fact, as an antidote to VUCA, I’ve coined another acronym, VACINE. It’s designed to inoculate organizations against this mad VUCA world in which our old models have grown increasingly useless.

V is for velocity. It’s clear that companies today have to move quickly. They have to be able to get their act together and move at the speed of the market, their customers, and the ecosystem in which they operate. The next chapter of this book is completely dedicated to speed, and how fast companies have to be able to move nowadays.

A is for agility. Speed alone is not enough. Agility is about being able to move quickly and swiftly—to be able to turn on a dime. It is about the capacity to change, to respond, and to transform. Agility is all about being nimble and being quick on your feet. In the sport of boxing, there is the phrase “roll with the punches.” For companies, this means coping with and withstanding adversity by being flexible.

One of my favorite examples of agility comes from the French telco company Free. Its biggest competitor, Bouygues Telecom, launched a big promotion campaign. The latter was probably convinced that it would be able to steal away quite a few of Free’s customers. But, powered by big data intelligence and a firm knowledge of how low the company was able to go (pricewise, of course), Free launched a cheaper counteroffer just one hour later. Talk about speed of reaction. And Free got quite a lot of visibility from this, stating that it was not the cheapest in the market for merely one hour.

Some of the largest and most innovative companies I know started out as something completely different. But they were smart enough to recognize a better opportunity ànd agile enough to make the flip. IBM (founded in 1911) originally sold commercial scales and punch-card tabulators; later on, it sold massive mainframe computers; and today it is all about software and consulting and IT services. Corning (founded in 1851) used to create the glass enclosures around Thomas Edison’s lightbulbs. Now it specializes in optical fibers, cell phone covers, telescopic mirrors, and television screens.7 The William Wrigley Jr. Company started out as a soap and baking powder company in 1891. In 1892, it offered chewing gum with each baking powder package. When it saw that the chewing gum was growing more popular than the baking powder, Wrigley reoriented itself. There can be a lot of luck and serendipity involved in innovation, but the real trick is being able to turn with the opportunities that present themselves. A lot of larger companies are too bureaucratic and too slow to manage that.8

C is for creativity. In today’s whirlwind economy, creativity has become an asset to cherish. Companies that fail to maintain a creative edge fall fast and hard. If you examine the stumbles of once-giants like Nokia or RIM BlackBerry, you see that they tumbled soon after they suddenly lost their creative flair. Legendary for adding his own creative touches to Apple products, Steve Jobs talked about “connecting the dots.” As he phrased it, “You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future. Because believing that the dots will connect down the road will give you the confidence to follow your heart even when it leads you off the well-worn path. And that will make all the difference.”

I is for innovation. Innovation has become the lifeblood of organizations. “Innovate or die” was once the mantra of the high-tech industry, but today the rate of change in many markets is picking up so fast that the motto has become mainstream. Innovation, the ongoing effort to develop new ways to solve current and future problems, is the main driver of differentiation and sustainability. It determines the ability of an organization to remain relevant amidst continuous and constant change.

N is for network. I believe that a major shift will occur in the way we adopt the network within our organizations. This book focuses on the rise of network effects in markets and what this means for companies. In a nutshell, I believe that markets are turning into networks of information, with the customer at the heart of those networks. This means that we can’t “market” anymore; instead, we have to be able to “influence” networks of information. And if the outside world becomes a network, then the inside has to become a network as well. Companies will survive in the age of networks only if they become networks of innovation internally.

E is for experimentation. Finally, and perhaps most important, companies will have to learn to adopt a culture of experimentation. In many companies, failure is an absolute taboo. Companies today are set up to execute strategy and implement five-year plans, but they’re still learning the art of experimentation. Start-ups, on the other hand, already experiment all the time. They are not afraid to fail.

Some of the most successful start-ups in Silicon Valley have adopted the “fail fast forward” principle, under which they encourage people to try many things, ruthlessly kill what doesn’t work, and amplify what has potential. The purpose of failing fast is to understand what doesn’t work and to learn from your mistakes. Building a culture of experimentation means implementing an attitude toward risk that will be necessary to survive in a world in which strategy becomes fluid. Some of the most avid advocates of this approach can be found at FailCon, a one-day conference for technology entrepreneurs, investors, developers, and designers who study their own and others’ failures in order to learn from them.9 You have to be a certain kind of brave to be prepared to admit in front of your peers that you made a mistake. But just imagine the energy and the insights that can arise from such a “learn from your failures” network.

But it is not only start-ups that are embracing this approach. An increasing number of larger or growing companies are using the same kind of “fail fast” methodology. Susan Wojcicki, Google’s senior vice president of advertising, understood this very well. She incorporated “never fail to fail” into her “eight pillars of innovation” a while ago. Spotify, for instance, performs small-scale “quick and dirty” experiments that are terminated really fast when they don’t work.10

Pixar too, one of the most creative and innovative companies in the film industry, has a unique take upon failure. In the words of Pixar cofounder Ed Catmull: “[Many people] think it means accept failure with dignity and move on. The better, more subtle interpretation is that failure is a manifestation of learning and exploration. If you aren’t experiencing failure, then you are making a far worse mistake: you are being driven by the desire to avoid it. And, for leaders especially, this strategy—trying to avoid failure by outthinking it—dooms you to fail.”11

The rest of this book will help you put VUCA in perspective, and will hopefully help you implement VACINE in order to cope with this ever-faster pace of change in our markets and our companies.

The days of long-term strategy are probably over, never to return. It’s about being nimble and fast, responsive and agile. As the great philosopher Mike Tyson once said, “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the face.”

As Herman Kahn wrote, after describing the horrible outcomes of global thermonuclear war, “We sincerely hope that the reader has a slightly uncomfortable feeling at this moment.” It was a classic example of Kahn’s black humor. I can imagine that you also feel slightly uncomfortable after reading this chapter, its descriptions of VUCA, and the end of long-term planning. But rest assured, the aim of this book is not to alarm you, but to guide you through this Age of Uncertainty.