Chapter 1

A Buoyant Decade, a Fragile System, and Some Leaders at Its Apex

We still continue in a period of unbounded prosperity. This prosperity is not the creature of law, but undoubtedly the laws under which we work have been instrumental in creating the conditions … There will undoubtedly be periods of depression. The wave will recede; but the tide will advance. (December 2, 1902)

The Nation continues to enjoy noteworthy prosperity. (December 6, 1904)

The people of this country continue to enjoy great prosperity. (December 5, 1905)

As a nation we still continue to enjoy a literally unprecedented prosperity; and it is probable that only reckless speculation and disregard of legitimate business methods on the part of the business world can materially mar this prosperity. (December 3, 1906)

—President Theodore Roosevelt, State of the Union Addresses

Theodore Roosevelt’s State of the Union addresses emphasized themes of economic triumph and regulatory caution; and they signaled a shift in America’s political economy. The first decade of the twentieth century marked the twilight of the Gilded Age and the rise of the Progressive Era. It also saw the ascendancy of American economic power on the global stage after dreadful cycles of growth and depression since the Civil War.

An economic boom from 1897 to 1906 reflected the benefits of technological change, surging exports, and a growing urban workforce. And the boom challenged longstanding orthodoxies about the economy and government’s role in it. The leading agents of such challenges were not extremist outsiders to the economic and political systems, but ironically were leaders in business and government. Hence, both the boom and the leaders underpin the Panic of 1907.

The Boom

In 1906, the American economy had completed an extraordinary run of prosperity that overshadowed any previous 10‐year period since 1806. Figure 1.1 shows that the 38 percent growth in GDP per capita from 1897 to 1906 simply dominated the decades before.

Preceding this boom period was the depression of the 1890s—the worst in the nineteenth century, according to economic historian Richard McCulley.1 The depression of the 1890s ended in June 1897.2 From 1897 to the end of 1906, the nation’s industrial production then grew an average of 6.5 percent per year, almost doubling the absolute size of U.S. factory output.

Over the same period, the variability of annual growth declined over time, perhaps reflecting the growing size, maturity, and industrialization of the economy. Figure 1.2 compares the period 1897–1906 with earlier episodes of U.S. economic development. It shows that the U.S. economy in 1906 was larger, had been growing faster than ever, and yet experienced less volatility in its growth.3

The dramatic growth and economic development of the United States at the turn of the century drew huge capital flows, especially from Europe. In 1895 the U.S. economy added $2.5 billion to its fixed plant and inventories, and by 1906 the annual rate of capital formation was running at nearly $5 billion, a blistering pace (see Figure 1.3). Much of this was financed by the country’s exports, which appeared as a bulging current account surplus after 1896. But even exports were insufficient to finance the very large growth rate in the formation of capital in 1905 (12.7 percent) and 1906 (21.8 percent).

Figure 1.1 10‐Year Periods of Growth in GDP per Capita

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data in Maddison Project Database, version 2020. Jutta Bolt and Jan Luiten van Zanden, “Maddison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy. A new 2020 update” (2020), https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database-2020?lang=en.

An attribute of long and large booms is buoyant optimism that leads to speculation and rapid growth in asset prices. Theodore Roosevelt’s State of the Union addresses during this decade acknowledged prosperity repeatedly. From 1897 to 1906, the number of newspaper articles mentioning “optimism” more than doubled.4 And in 1906, headlines reported “The Chicago Market: Optimism Is General,”5 “Canadian Outlook Bright: Optimism General in Industrial and Financial Circles,”6 “Chicago Building Boom: One Hundred Million in 1906 for New Building and Construction Work,”7 “Land Boom in Southwest,”8 “Building Boom in Atlanta: Nearly 100 Per Cent Increase Over Last October, and Bids Fair to Continue,”9 “Conditions in Chicago: All Industries There Working Under High Pressure. Railroad Traffic Continues to Break All Records…,”10 and “Iron and Steel Notes: No Summer Let up for Steel Workers, Owing to Great Boom.”11

Figure 1.2 Comparison of U.S. Economic Performance Over Three Episodes

NOTE: The size of the circles indicates the relative size of the U.S. gross domestic product per capita at 1865, 1896, and 1906, respectively. The growth rate is the compound annual average over each period. The coefficient of variation is a measure of relative volatility of growth (calculated as the standard deviation of growth rates divided by the compound average rate of growth for the period).

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data from Maddison Project Database, version 2020. Jutta Bolt and Jan Luiten van Zanden, “Maddison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy. A new 2020 update” (2020), https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database-2020?lang=en.

The growth in stock prices at a 16 percent compounded annual rate over this decade mirrored such optimism. Figure 1.4 shows the dramatic rise—and volatility—in share prices over the boom decade. The slump in stock prices in 1903 was variously attributed to Roosevelt’s trust‐busting, high interest rates, and the reversal of stock‐price manipulation schemes, all of which resulted in a “rich men’s panic.”12 The fears engendered in that slump did not materialize, prompting a large recovery in stock prices.

Figure 1.3 Macroeconomic Trends, 1895 to 1906

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data from FRED Macrohistory Database, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Figure 1.4 Growth in Stock Prices During the Boom Decade

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data from National Bureau of Economic Research, “Average Prices of 40 Common Stocks for United States,” retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, April 30, 2022, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M11006USM315NNBR.

Wall Street Financial Leaders

Into the prodigious demand for capital moved financiers in New York and London who possessed the sophistication and credibility to raise the necessary funds for America’s factories and infrastructure in the world’s capital markets.13 And over this time, the undisputed leader of the financial community in the United States was J. Pierpont Morgan. Among the major industrial combinations that he arranged were firms that remained memorable a century later: American Telephone and Telegraph, International Harvester, American Tobacco, National Biscuit (Nabisco), and others.14 In 1901, Morgan played a central role in the formation of U.S. Steel, the largest corporation in America. Capitalized at a value of $1 billion, U.S. Steel was twice the size of the entire budget of the U.S. government in 1907.

A complex man, Morgan was a forceful personality, as all biographers agree. Historian William Harbaugh wrote of Morgan, “What a whale of a man! There seemed to radiate something that forced the complex of inferiority.”15 Morgan’s nickname on Wall Street was “Jupiter,” suggesting his place in the financial community. Biographer Frederick Lewis Allen described Morgan’s attitude about the role of the Wall Street financial leaders: “When he put his resources behind a company, he expected to stay with it; this, he felt, was how a gentleman behaved.”16 Historian Vincent Carosso added,

If he had any fundamental, guiding business policy at all, it was to promote stability through responsible, competent, economical management, and to be aware of his obligations to an enterprise’s owners and bondholders. There was nothing he disliked more than unrestricted competition and aggressive expansionism, which he considered wasteful and destructive. Morgan believed in orderly industrial progress, and he endorsed policies aimed at promoting cooperation. Large enterprises, he affirmed, should adhere to the principle of community of interest, not the Spencerian doctrine of survival of the fittest.17

Two important figures in Morgan’s circle were George F. Baker, president of First National Bank of New York, and James Stillman, president of New York’s National City Bank, the largest in the United States.18 Stillman and Baker had been both allies and competitors of Morgan in corporate financial transactions. The three men commanded great mutual respect, having worked together in business and on charitable boards.

Baker and Pierpont Morgan were close friends; they esteemed each other and shared similar views on business matters. Morgan’s son once told a biographer, “Mr. Baker was closer to my father than any other man of affairs. They understood each other perfectly, worked in harmony, and there was never any need of written contracts between them.”19 Stillman, on the other hand, was somewhat of an outsider, born and raised in Brownsville, Texas. Biographer Anna Robeson Brown Burr suggested that the relationship between Stillman and Morgan was more distant, “one of respect, though they did not always see eye to eye.”20

The success of Morgan and his circle in attracting foreign capital to America’s “emerging market” was reflected in the immense importations of gold in 1906:21 the inflow of gold to the United States spiked sharply upward to $165 million, dwarfing all annual gold flows after the Civil War, except during the year of a significant economic downturn in 1893. Fortunately, gold was plentiful in the global economy. The exploitation of gold discoveries in South Africa (beginning in 1886) and the Klondike region of Canada (beginning in 1896) contributed to a doubling of the stock of monetary gold in the United States between 1896 and 1906.22

America’s ability to attract gold reflected its commitment to the gold standard, the backing of paper currency by a commitment to convert to gold coin on demand. This commitment became political reality with the defeat of William Jennings Bryan for president in 1896 (Jennings favored a bimetal standard of gold and silver) and with Congress’s passage of the Gold Standard Act in 1900. From 1897 to 1906, growing gold reserves at the U.S. Treasury prompted easy credit conditions.

America’s rapid industrialization during this period also hastened the emergence of business entities of unprecedented scale, complexity, and power. Between 1894 and 1904, more than 1,800 companies were consolidated into just 93 corporations.23 Some of these large firms had grown by buying up smaller competitors during times of economic distress, while others were organized by financiers seeking to control competition and build efficiencies of scale.a Much of the volume of new debt and equity financing for these large corporations again flowed through a relatively small circle of financial institutions in New York, including J. P. Morgan & Company; Kuhn, Loeb & Company; the First National Bank; the National City Bank; Kidder, Peabody & Company; and Lee, Higginson & Company.24

The turbulence of this decade was reflected in at least four precedent‐setting developments. First, a financial brawl in 1901 for control of the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad (CBQ) highlighted the growing aggressions of industrialists and resulted briefly in a monopoly that would control rail traffic in the U.S. Pacific Northwest. J.P. Morgan brokered a deal between two rail barons, James J. Hill and Edward H. Harriman, to form the Northern Securities Corporation. But President Theodore Roosevelt sued the company under the Sherman Antitrust Act, a law that up to then had been enforced indifferently. The suit worked its way to the Supreme Court, which in 1904 disbanded the monopoly. This was a pivotal case in antitrust law and lent momentum to government regulation in the Progressive Era.

Second, from May to October 1902, anthracite coal miners waged an industry‐wide strike for better pay and safer working conditions. Mine operators and railroads refused to negotiate. Worried that the supply of coal for home heating would dwindle with the onset of winter, President Roosevelt arbitrated negotiations to settle the strike. This was the first presidential labor arbitration in U.S. history.

Third, investigative journalists, such as Ida Tarbell, highlighted anticompetitive behavior. Her book The History of the Standard Oil Company, published in 1904, exposed anticompetitive tactics of John D. Rockefeller and his colleagues. It prompted public outrage and more antitrust action by President Roosevelt.b

Finally, in 1905 a scandal among the directors and management of the Equitable Life Insurance Company highlighted excesses of the Gilded Age. A young heir had used the resources of the firm for personal purposes. The scandal prompted New York State to tighten regulation of the industry.

Such examples tarnished big businesses and tycoons in the eyes of the public. They seemed to affirm capitalists’ excesses reported by muckraking journalists. And they lent momentum to the reforms of the progressives.

A Fragile System

Notwithstanding the apparently buoyant economic conditions, the financial sector of the U.S. economy harbored vulnerabilities that would figure prominently in the panic. The first vulnerability emanated from the unusually large number of small banks in the nation.

Other nations such as Britain, France, Germany, and Canada hosted a banking industry consisting of a small number of large institutions that had branches across many locations. But since the days of Andrew Jackson, politicians had feared the rise of bankers who might wield too much influence. Accordingly, U.S. regulations limited the ability of banks to open branch offices and to extend their operations across state lines.

Regulations also permitted relatively easy entry by new institutions, a policy that suited the growing nation. By 1906, the number of banking institutions expanded to 21,986,25 growing at a rate faster than the growth rate of the population or the GDP per capita, as Figure 1.5 shows. The proliferation of banks far exceeded the rate of growth that would have been consistent with the economy. Most of these institutions were small, and typically held loan portfolios concentrated in local businesses, such as agriculture. A widespread shock, such as a single bad harvest, could challenge the stability of these banks.

The second major strain on the financial system during the runup to the Panic of 1907 was the large growth in debt financing. Between 1897 to 1906, loans by national banks nearly doubled. Since the capital markets were accessible only by large firms and the most creditworthy borrowers, bank lending remained the main source of financing in the country. The contemporary economist O.M.W. Spraguec noted that the economic recovery of 1897–1906 left banks awash in new deposits, which fueled the boom in bank credit.

Figure 1.5 Growth of Banking Institutions

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data in Series X 580‐587, “Financial Markets and Institutions,” in Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census).

Figure 1.6 shows that from 1897 to 1903, the growth in loans by national banks tracked the growth in industrial production and in gross national product (GNP)—but from 1904 to 1906, bank lending outgrew these benchmarks: by the end of 1906, actual loan volume exceeded the volume implied by industrial production by $630 million (13.5 percent) and GNP by $376 million (8 percent). Sprague asserted that the excess bank loans went to the call money market, largely fueling speculation in stocks.26

Figure 1.6 Loans of National Banks Compared to GNP

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data in Sprague (1910), p. 218. Data on GNP Series F1‐5, “Gross National Product, Total and per Capita, in Current and 1958 Prices,” in Historical Statistics of the United States from Colonial Times to 1970, Part 1, Chapter F (Washington DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census).

Third, over the 10 years from 1897 to 1906, the safety cushion of banks declined. Net deposits grew at a compound rate of 9.2 percent annually, but cash reserves did not grow quite as fast (only 6.1 percent), in part because banks loaned or invested their cash more aggressively. Figure 1.7 shows the decline in the ratio of cash reserve to net deposits for national banks by almost one‐third over this period—from 17.8 percent to 13.3 percent, below the minimum reserve ratio allowed by federal regulations. It is worth noting that much of the decline in reserves occurred in the interior region of the United States—in late 1906, the reserve ratio of national banks in New York City remained at 25.5 percent, just above the required minimum for banks of their stature.

The decline in financial condition of the national banks revealed little about the condition of state‐chartered banks, which vastly exceeded the number of nationally chartered banks. Generally, these were small institutions and less resilient to financial shocks. To compound the worrisome decline in the bank reserve ratio, the practice of fractional reserve banking placed some part of most banks’ reserves on deposit with banks in reserve cities, where the deposits could earn interest. When the banking system functioned properly, these distant reserves could be recalled on demand. But during a panic, a suspension of specie withdrawals would prevent access to those distant reserves.

Figure 1.7 Condition of National Banks

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data in Sprague (1910), p. 218.

Also, the advent of trust companies into the banking business—about which more will be said later—complicated any assessment of the condition of the financial system. The trust companies intruded into the banks’ competition for deposits by lending money more liberally, carrying lower cash reserves to backstop depositors’ claims, and enjoying lighter prudential regulation.

Fourth, this was a period that had been preceded by regular financial crises. Fragility mattered because of the memory—vivid in the recall of most people in 1906—of the frequent banking panics in nineteenth‐century America. A panic featured “runs” by depositors, seeking to withdraw their funds in specie from banks. By virtue of their low ratios of reserves to deposits, banks faced the prospect of exhausting their cash. To prevent that outcome, they would suspend depositors’ right to withdraw cash until the panic subsided. This left firms and individuals in the lurch, possibly unable to buy food, pay rent, or meet their own debt obligations. Bank panics led to serious spillovers into the real economy. Figure 1.8 shows that from 1820 to 1915, America endured 11 serious bank panic episodes, most associated with economic recessions.

Figure 1.8 Major Bank Panic Episodes and Changes in Industrial Production

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data on industrial production in Davis (2004), pp. 1177–1215.

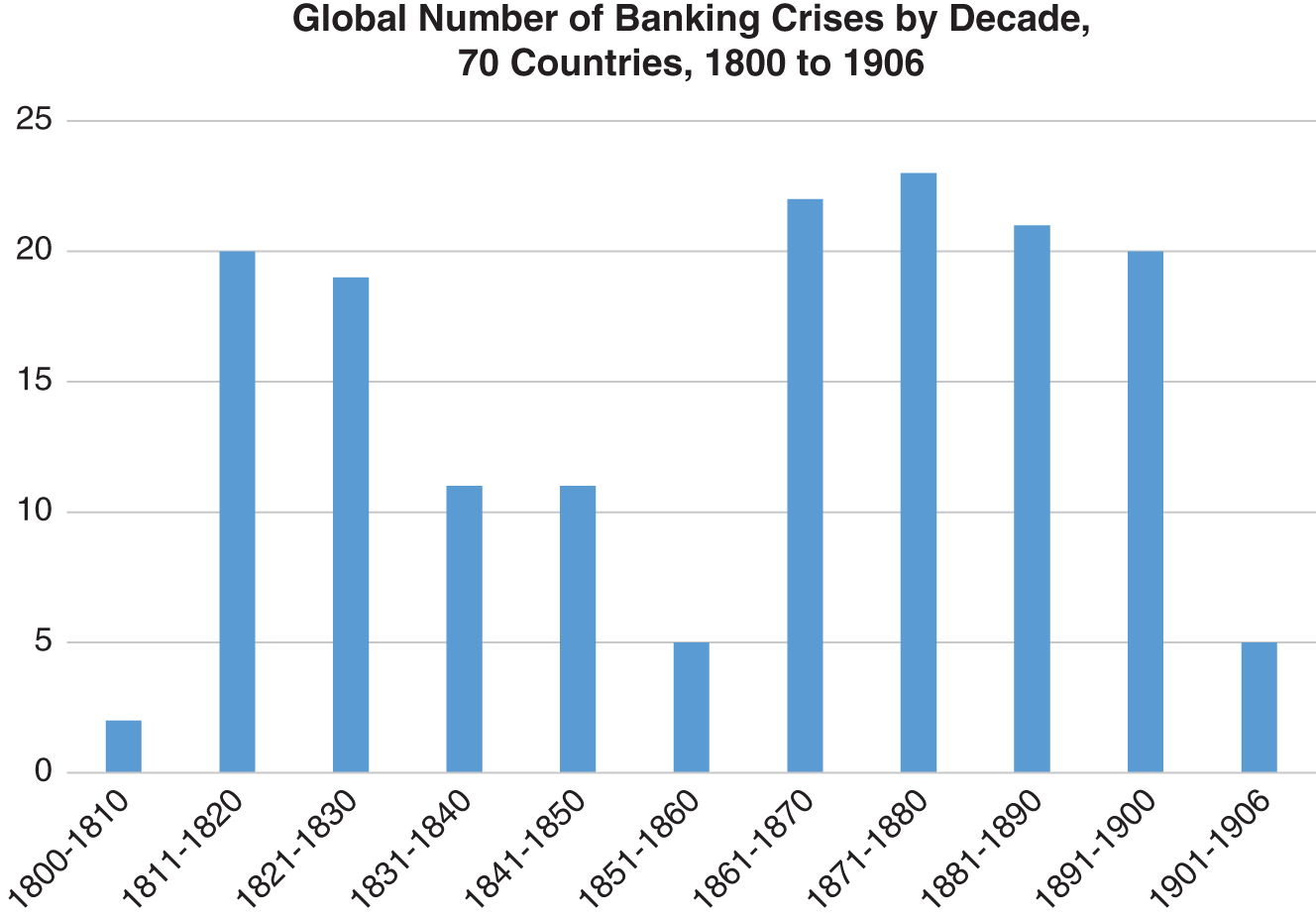

The United States was not alone in its difficulties of finding a model for stable banking. Figure 1.9 shows that the eruptions of bank panics were the rule rather than the exception throughout the nineteenth century among 70 countries in the world. Each decade, an average of 14 countries experienced financial crises.

A Growing Movement for Stability in the United States

The instability of the financial system had been a source of concern to national leaders and the public at least since the founding of the nation. At the behest of Alexander Hamilton, in 1791 Congress enacted a charter for the Bank of the United States. Through its large size, ample reserves, and multiple branches, it functioned as a disciplinarian on banks in the fledgling republic that failed to conduct business prudentially.

Figure 1.9 Number of Country Bank Panics per Decade

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data from “Global Crises Data by Country,” Behavioral Finance & Financial Stability, Harvard Business School, downloaded July 28, 2021 from https://www.hbs.edu/behavioral-finance-and-financial-stability/data/Pages/global.aspx.

Unfortunately, the growing influence of the Bank of the United States worried Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who mounted a successful campaign against renewing the bank’s charter in 1811. The War of 1812 proved to be a harsh awakening to the usefulness of such a big bank. Thus, in 1816, Congress chartered the Second Bank of the United States. But again, a destabilizing banking crisis and recession in 1819 inflamed public sentiment toward banks and the Second Bank, in particular.

One important antagonist, Andrew Jackson, was elected president in 1828 on the promise of fighting the Second Bank of the United States. Although Congress passed a recharter of the Second Bank, Jackson vetoed it in 1832, ending its prudential oversight of the banking system. Then, in laws passed in 1863 and 1864, Congress permitted the national chartering of banks and the creation of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, which would monitor those banks. Nonetheless, serious banking crises in the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s gradually persuaded business leaders that the unusual architecture of bank regulation was not working.

Reform proposals sprouted. These included authorization for national banks to expand their issuance of banknotes in a panic (1894),27 to establish regional reserve banks (1896),28 to establish a confederation of regional reserve banks (1901),29 to deploy the Treasury’s surplus gold to national banks at the height of the crop‐moving season (1902),30 to allow bank clearing houses to issue their own asset‐backed banknotes during a panic (1904),31 and, ultimately, to establish a central bank along the lines of major European countries (1906).32

The financial community’s proposals to establish a central bank met with hostile opposition from progressives, populists, “Main Street” businesspeople, and country bankers. All believed that the existing powers of the U.S. Treasury to shift gold deposits as needed trumped the interests of Wall Street and best served the interests of the public. In his State of the Union message to Congress on December 3, 1906, President Roosevelt sided with the opposition: “Any plan must … guard the interest of Western and Southern Bankers as carefully as it guards the interests of New York or Chicago bankers and must be drawn from the standpoints of the farmer and the merchant no less than from the standpoints of the city banker and the country banker.”33

In his annual report to Congress of December 5, 1906, Treasury Secretary Shaw argued that instead of creating a central bank, the Treasury Department should be empowered to control bank reserves and the money supply. In effect, this would designate the Treasury as the de facto central bank. Shaw feared that private interests (such as bankers) would take control of an independent central bank. Therefore, Shaw proposed that Congress should create a reserve fund of $100 million to deploy in the event of a crisis for use by the Secretary of the Treasury. He said, “in my judgment no panic as distinguished from industrial stagnation could threaten either the United States or Europe that he could not avert.”34 Events in 1907 would challenge his confident assertion.

The reforms proposed between 1894 and 1906 were notable for at least three reasons. First, they reflected the beginnings of a dramatic shift in mainstream thinking about monetary management in the United States. The old Jefferson–Jackson antipathy toward banks poorly served the needs of a nation growing rapidly. Second, the hostility they aroused displayed the new fault lines in American politics that monetary policy would encounter for decades to come. Third, they reflected components of what eventually would become the Federal Reserve System, an institution that would manage the supply of currency, pool risks, regulate banks, and fight crises as a lender of last resort.

A Portent

Those closest to the financial system saw these difficulties and their attendant risks most clearly. On January 4, 1906, with unusual clairvoyance, Jacob Schiff, senior partner of the house of Kuhn, Loeb & Company (J. P. Morgan’s archrival), gave a speech to the New York Chamber of Commerce in which he declared presciently, “the money market conditions which had prevailed the previous sixty days are a disgrace to the country, and that unless our currency system was reformed a panic would sooner or later result compared with which all previous panics would seem as child’s play.”35

By 1906 J. Pierpont Morgan himself was beginning to disengage slowly from the day‐to‐day activities of his firm to attend to his passion for collecting art and literature, serving on boards of charitable institutions, and touring Europe. He relied heavily on his son, J. P. “Jack” Morgan Jr., to manage his firm’s daily affairs, as well as his right‐hand man, George W. Perkins, a partner in J. P. Morgan & Company. On April 17, 1906, the aging Morgan turned 69 years old. By this time, he was unquestionably, according to biographer Anna Burr, “the most powerful figure in the American world of business, if not the most powerful citizen of the United States. His authority was vague, but it was immense—and growing.”36

On the morning after Morgan’s birthday, an historic catastrophe devastated the city of San Francisco, California, setting in motion a chain of events that would eventually call for all the power, wisdom, strength, and influence that Old Jupiter could muster.

Notes

- a. The companies these financiers organized were popularly called “trusts,” which a leading economist of the day defined as “an organization managed by a board of trustees to which all the capital stock of the constituent companies is irrevocably assigned; in other words, the original shareholders accept the trustees’ certificates in lieu of former evidences of ownership.” [See Ripley (1916), p. xvii.] The first and most famous of these business entities was John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust, created in 1882.

- b. Eventually, in 1911, the U.S. Supreme Court would order the breakup of the Standard Oil Trust into some 30 separate companies.

- c. Oliver Mitchell Wentworth Sprague published in 1910 an authoritative account of U.S. financial crises under the aegis of the National Monetary Commission. At the time, he was assistant professor of banking and finance at Harvard University. Sprague’s book is a starting point for commentaries on the Panic of 1907. Hereafter, for simplicity he will be cited as Professor Sprague.

- 1. McCulley (2012 [1992]), p. 26.

- 2. “US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions,” National Bureau of Economic Research, downloaded August 21, 2022 from https://www.nber.org/research/data/us-business-cycle-expansions-and-contractions.

- 3. The analysis of growth rates draws on indices of U.S. industrial production drawn from “U.S. Industrial Production Index” of the National Bureau of Economic Research, downloaded from www.nber.org/data/industrial-production-index/.

- 4. Using the ProQuest Historical Newspapers search engine covering 10 major and regional newspapers, we searched for the number of articles containing the word “optimism.” From 1897 to 1906, the trend rose from 124 to 336.

- 5. “The Chicago Market: Optimism Is General—Better Outlook for Investment Business—Numerous Active Stocks” Wall Street Journal, January 26, 1906, p. 8.

- 6. “Canadian Outlook Bright: Optimism General in Industrial and Financial Circles,” Wall Street Journal, June 12, 1906, p. 8.

- 7. “Chicago’s Building Boom: One Hundred Million in 1906 for New Building and Construction Work,” Wall Street Journal, May 29, 1906, p. 3.

- 8. “Land Boom in Southwest: Railroads Carrying Out Great Trainloads of Homeseekers, Business Men Large Buyers,” Wall Street Journal, September 5, 1906, p. 5.

- 9. “Building Boom in Atlanta: Nearly 100 Per Cent Increase Over Last October, and Bids Fair to Continue,” Wall Street Journal, November 1, 1906, p. 8.

- 10. “Conditions in Chicago: All Industries There Working Under High Pressure. Railroad Traffic Continues to Break All Records. Big Movement of Grain Begins. Factories Maintain Record Output “Boom” in Real Estate Not Gaining Much Headway.” Wall Street Journal, September 15, 1906, p. 8.

- 11. “Iron and Steel Notes: No Summer Let Up for Steel Workers, Owing to Great Boom,” New York Times, June 24, 1906, p. 11.

- 12. See Noyes (1909a), p. 186.

- 13. In part, the financial houses these financiers built served as a certification of quality that the securities of U.S. firms being sold in Europe were attractive investment opportunities.

- 14. Other companies under the influence of Morgan also included Adams Express Co.; Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroad; Baldwin Locomotive Co.; Chicago–Great Western Railroad; Erie Railroad; International Agricultural Co.; International Mercantile Marine Co.; Lehigh Valley Railroad; New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad; Northern Pacific Railroad; New York Central Railroad; Pere Marquette Railroad; Philadelphia Rapid Transit Co.; Public Service Corporation of New Jersey; Pullman Co.; Reading Railroad; Southern Railroad; United States Steel Co; and Westinghouse Co.

- 15. Harbaugh (1963), pp. 157–158.

- 16. Allen (1952), p. 79.

- 17. Carosso (1987), p. 288.

- 18. V. I. Bovykin and Rondo Cameron (Eds.), International Banking 1870–1914 (Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 67.

- 19. Logan (1981), p. 163.

- 20. Burr (1927).

- 21. Gold was typically imported through the sale of bonds or other promises to repay.

- 22. U.S. Bureau of the Census, “Financial Institutions and Markets,” Historical Statistics of the United States (Washington, DC: Department of Commerce, 1975), Series X 410‐419.

- 23. N. R. Lamoreaux, The Great Merger Movement in American Business, 1895–1904 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), p. 2.

- 24. De Long (1991), p. 3.

- 25. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970 (Washington, DC: Department of Commerce, 1975), Series X 580‐587, p. 1019.

- 26. Sprague (1910), p. 239.

- 27. In 1894, the American Bankers Association proposed allowing national banks to expand their issuance of banknotes in a panic. That same year, the Secretary of the Treasury and the Comptroller of the Currency both proposed steps for alleviating a liquidity crunch.

- 28. Late in 1896 and early 1897, large gatherings of business leaders sought to mobilize a national movement for financial reform. The resulting conferences developed proposals in 1900 for the establishment of regional central banks, none of which attracted congressional support.

- 29. In 1901, the departing Secretary of the Treasury, Lyman Gage, proposed the creation of a central bank, to be structured as a confederation of regional banks, rather than a unitary bank such as the Bank of England. He envisioned the confederation of reserve banks funded by the banks themselves and focused on concentrating and distributing “unemployed reserves from sections where such reserves were not needed, … as loans where most needed” (U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the Finances for the Year 1901,” 77, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/treasar/AR_TREASURY_1901.pdf).

- 30. In 1902, Gage’s successor, Treasury Secretary Leslie Shaw, began a policy of monetary management to thwart the liquidity crunches that typically occurred during the crop‐moving season. His aim was to make the money supply more elastic. Nevertheless, Shaw’s experiments were criticized as “dangerous and indefensible” (A. Piatt Andrew, “The Treasury and the Banks Under Secretary Shaw,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, August 1907, 566.)

- 31. In 1904, Senator Orville Pratt floated a trial balloon proposing the use of bank clearing houses to deal with bank crises. The novel suggestion was that clearing houses should issue their own asset‐backed banknotes, and thus reflected the advantage of pooling bank reserves behind currency.

- 32. In 1906, the New York Chamber of Commerce chartered a committee to study the financial system. In November the committee recommended “centralization of financial responsibility … [and] creation of a central bank of issue under control of the government … [as] the best method of providing an elastic credit currency … [to be] privately owned or distributed among the banking institutions of the country” (quotation of NY Chamber of Commerce Committee report in McCulley (1992), 127.) This report was the first formal proposal to establish a central bank. Not to be outdone, the American Bankers Association prepared a detailed plan for banks to issue national currency.

- 33. President Theodore Roosevelt, State of the Union Address, December 3, 1906, accessed July 27, 2021 from https://www.infoplease.com/primary-sources/government/presidential-speeches/state-union-address-theodore-roosevelt-december-3-1906.

- 34. U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the Finances for the Year 1906,” 49, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/treasar/AR_TREASURY_1906.pdf.

- 35. Commercial and Financial Chronicle, January 4, 1907, p. 6.

- 36. Burr (1927), Volume 25.