Chapter 3

The “Silent” Crash

The whole situation is most mysterious; undoubtedly many men who were very rich have become much poorer, but as there seems to be no one breaking, perhaps we shall get off with the fright only.1

—J. P. “Jack” Morgan Jr., March 14, 1907

It is a rich‐man’s panic and the results, however serious, will not be disastrous.2

—Barton Hepburn, chairman of Chase Bank, March 15, 1907

By early 1907, it seemed that the progressive tightening of money, which had been accelerated by the massive capital demands of San Francisco’s earthquake, had precipitated a slow decline in equity prices—considered by some contemporaries to be a “silent” crash in the U.S. financial markets.

The Crash

Between its peak in September 1906 and the end of February 1907, the index of 40 industrial stocks fell 10.9 percent,3 a five‐month change in value unremarkable in view of the long history of the market, but pertinent as the precursor to the events of March. Indeed, on March 6, 1907, telegraph correspondence between Jack Morgan and his partner in J. P. Morgan & Company’s London affiliate, Teddy Grenfell, reflected the deepening anxiety between the world’s financial centers:

Grenfell: Can you give us any information and what is your opinion of the immediate future of your market?4

Morgan: Do not get any information showing real trouble our market although of course continued liquidation must hurt some people and may do severe damage in places. From what I can make out do not think stocks are in weak hands. Shall be surprised if immediate future brings much more liquidation, although of course impossible form opinion.5

In the coming days, Teddy and Jack exchanged more anxious telegrams about rumors of gold shipments. Grenfell thought that at the “first indication [of] considerable withdrawals of gold,” the Bank of England would raise its interest rate. He wondered whether the U.S. Treasury would relieve the situation by releasing gold from its vaults into the financial system. On March 13 Jack wired back that he could discover no intentions to ship gold from London this week, although there might be attempts to buy gold next week.6

By mid‐March the “silent” crash had become audible as equity prices turned decidedly and sharply for the worse. Declining over a series of days (March 9 to 14 and 23 to 25), the index of all listed stocks fell 9.8 percent. Especially damaged were shares in shipping (off 16.6 percent), mining (down 14.5 percent), steel and iron (down 14.8 percent), and street railways (off 13.8 percent). Railroad companies were especially hard‐hit: over half of the 25 most active stocks on March 14 were rails, led by Northern Pacific, down 72.9 percent; Union Pacific, off 59.9 percent; Great Northern (preferred), off 58.2 percent; and Reading Railroad, down by 44.3 percent. One estimate placed the worst trading day of the month on March 14, with a statistically significant loss of 8.29 percent in the industrials index.7 The Commercial and Financial Chronicle, the principal financial periodical at the time, observed, “The liquidation going on in Wall Street … is phenomenal. Stock sales … are among the high records in the Stock Exchange history.”8

The proximate trigger for the slump in stocks was the apparent failure of Edward H. Harriman and National City Bank to successfully “boom”a the stocks of the Union Pacific Railroad (UP) and other railroads. Borrowing aggressively, UP had purchased shares in various railroad companies starting in June 1906. The railroad industry generally, and UP in particular, had mooted massive investments in new plant and equipment, for which equally massive security issues were in prospect—a billion dollars per year for five years, compared with the previous peak fundraising of $500 million in 1901.9 High security prices would help the process. So would high and rising dividends: in August 1906, UP had announced an increase in the dividend from 6 percent to 10 percent of par value. Professor Sprague wrote, “Events seem to have proved conclusively the ability of these companies to earn the dividends which were then declared, but nevertheless, coming when it did, this action exercised an unfortunately general influence. It gave encouragement to the unbridled optimism which was already too much in evidence. It was preceded and followed by a speculative movement on the stock exchange which was made possible through credits granted by the banks upon the foundation of the usual summer inflow of funds from the interior.”10

Concern about Policy Shifts

However, regime change was in prospect: years of complaints by populists and progressives about railroads’ monopolistic practices had culminated in passage of the Hepburn Act on June 29, 1906. This act empowered the Interstate Commerce Commission to set railroad rates, which raised howls of complaint from business leaders. Ultimately the loans to UP and other market speculators began to mature in February and March 1907, which forced the railroad boomers to confront the worsening credit conditions that had commenced with the Bank of England’s contractionary policy in the fall of 1906. Without other sources of finance, Harriman and other speculators were forced to dump their holdings onto the market. Sprague noted, “Never before or since have such severe declines taken place on the New York Stock Exchange.”11

J. Pierpont Morgan was absent from New York during these disturbances in the market; he had sailed for Europe at midnight on March 13, the date of the sharp market break. There, Pierpont met old friends, toured the art markets for possible acquisitions for his collection, and relaxed at various spas and villas. Meanwhile, Jack Morgan in New York grappled with the confusion and chaos in the financial system, writing in a letter to his partners in London on March 14:

Here we are, still alive in spite of the most unpleasant panic which we are going through. The whole trouble lies, in my mind, in the mystery of the conditions; no one seems to be in any trouble, there is money at a price for anyone who wants it, and in our loans, and in those of all the Banks I have talked to, there has been no trouble whatever of keeping the margins perfectly good, except the physical difficulty of getting the certificates round quickly enough… . I could not yesterday finish this letter owing to the panic and general trouble, there being so much to see to with Father and Perkins both away. Today, things seem to be so much quieter that I am in hopes that most of the trouble is over, certainly for the present… . The whole situation is most mysterious; undoubtedly many men who were very rich have become much poorer, but as there seems to be no one breaking, perhaps we shall get off with the fright only.12

As the price declines continued during the next week, rumors of the failure of financial institutions began to circulate. The London partners of J. P. Morgan & Company cabled to Jack: “London Daily Telegraph today states that house of international prominence has been helped in New York. Is there any truth in this? Who is it? Do you expect much further liquidation?”13 Jack replied, “As far as we know there is no truth in rumor international house having been helped. Newspaper reports here is that various stock exchange houses in London are in difficulties. Cable any information you can obtain. Urgent liquidation seems to be pretty well done but as many parties heavily hit look for depressed markets for some time.”14

The Treasury Acts

Amidst these rising concerns about market conditions in New York, leaders in Washington were also taking notice. Throughout the day and late into the evening on March 13, President Theodore Roosevelt (TR) called a series of meetings with members of his cabinet, including George B. Cortelyou, who had only begun his term as Treasury Secretary on March 4.

Cortelyou had served as the Secretary of Commerce and Labor and as Postmaster General in TR’s cabinet and Chair of the Republican National Committee during TR’s reelection campaign in 1904. Yet his stance on financial policy was unknown. Would Cortelyou continue the policy of his predecessor, Leslie Shaw, in deploying Treasury gold to stabilize banks?

Cortelyou advised the president that the Bank of England would likely raise its discount rate, thereby temporarily restraining the importation of gold to the United States and further straining the nation’s money supply. Given the urgent need for more—not less—liquidity, Cortelyou suggested that relief from the federal Treasury would urgently be necessary to quell a potential panic.

As rumors swirled that the market’s sudden decline was somehow a “premeditated panic” orchestrated by “Wall Street manipulators”15—a conspiracy theory (oddly) predicated on the concurrent departure of J.P. Morgan from New York for a European tour, Cortelyou acted. Following late‐night discussions with the president and Secretary of State Elihu Root, the Treasury announced a bold effort to calm investors and avoid a “money stringency,” infusing up to $71 million into the money supply. The plan included: an immediate buyback of $25 million in federal bonds; an order to keep in circulation $16 million in notes soon scheduled for retirement; and an agreement not to withdraw $30 million in cash that the Treasury had placed with the banks the previous fall. Cortelyou also arranged for federal customs collectors around the country to deposit all receipts with national bank depositories, providing immediate access to funds in those cities lacking federal subtreasuries.

The quick action by Treasury was considered at the time to be among the most sweeping relief measures ever implemented by the federal government. The New York Times noted that Cortelyou’s response was “far beyond [former Treasury Secretary] Shaw’s relief.”16 And, immediately following Cortelyou’s announcement, the market appeared briefly to stabilize, bringing forth accolades for Secretary Cortelyou’s efforts, who had barely warmed his seat at Treasury. The administration worried that a large federal intervention risked being regarded as a precedent, potentially signaling that market disruptions would always result in federal intervention in the money supply.17 Nevertheless, the positive response from the financial community was enthusiastic. “The prompt and clear action of Secretary Cortelyou saved the day,” said the prominent New York banker Jacob Schiff. “I have strong hopes that much of good will result from the present situation.”18

Yet the Slump Continues

This upbeat outlook was not to last. Notwithstanding initial hopes for a rapid restoration of calm, conditions remained unsettled as the unrest spread to other financial markets. On March 23, 1907, the Commercial and Financial Chronicle noted, “Lack of confidence [among investors] is never reflected more unerringly than in the money market; and the seriousness of the situation in that regard is shown in the inability of the railroads for over a year past to finance their new capital needs.”19 Both the municipalities of Philadelphia and St. Louis made bond offerings, and in neither case was the underwriting successful. “Money is commanding such high rates that it is impossible to float even gilt‐edged securities at the low figures offered by Philadelphia and St. Louis,” the Chronicle reported.

By now dubbed the “rich man’s panic” in the popular press, equity prices continued to fall in New York, following a slump in foreign markets over the weekend. Alarmed by the situation, on March 25 Cortelyou again counseled the president, recommending that further measures should be taken by the government to prevent a further “demoralization.”20 Guided by a sense that matters could spin out of control, the secretary left Washington for New York, with a plan to confer with financiers and other business leaders to discuss how to steady the market. Thus was hatched the second major federal response to the market panic in as many weeks.

Treasury Responds Again

On the morning of March 26, with the markets already in serious decline, Secretary Cortelyou issued a statement about an unconventional and creative approach to infusing more liquidity into the financial system. National Banks had to deposit U.S. government bonds with the Treasury to be held as reserves against banknotes in circulation; if the maturing bonds were not replaced, it would force a reduction in the nation’s money supply. In substitution for all U.S. 4 percent bonds maturing on July 1, Cortelyou announced that the Treasury would accept Philippine bonds and certificates, City of Manila bonds, Puerto Rican bonds, District of Columbia bonds, and Hawaiian bonds, as well as state, municipal, and high‐grade railroad bonds. Altogether these moves were expected to relieve pressure on investors, thereby keeping $12 million in circulation.

As if that were not sufficient, Cortelyou also extended his order for customs collections in subtreasury cities (including New York) to be deposited in those cities’ national banks. In addition, he authorized the immediate payment of interest on the federal bonds coming due in April 1907, which would be paid instantly in cash to any holders of these coupons. All told, this action added yet another $16,900,000 to the money market, providing a much‐needed automatic cash infusion. It was further reported that the Treasury was prepared to release $25 million to $30 million more, while still maintaining a working balance of $75 million.21

Then a Rally

The net result of the Treasury’s interventions was a phenomenal bull market rally on March 26, reinforced by the expectation that Cortelyou would eventually make permanent the emergency policy of depositing customs receipts with the banks rather than the subtreasury.22 “All this serves to confirm the bold and much criticized declaration made by Secretary Shaw [Cortelyou’s predecessor] in his last annual report,” extolled the editors of the Wall Street Journal, “that if he had a balance of $100,000,000 at his disposal, the United States treasury could at all times prevent any financial panic in any part of the world.”23

Indeed, by the end of the week, cables between J.P. Morgan’s partners suggested that the worst was past. On March 29, 1907, Jack Morgan reflected on the change in mood to his London associates:

The two panics within the last ten days have given people a big scare, and the losses of course are frightful. The fact that no one has failed is more of the nature of a miracle than of ordinary business, but it simply shows, as far as I can see, that practically no one was overtrading… . My own belief, however, is that the panic is over, and the fact that the Treasury is putting out money rather fast and that that action has really been the cause of the restoration of confidence makes me feel that it was at bottom a money panic. Not a money panic such as we have heretofore had, but an apprehension that, in view of enormous calls being made upon huge stock issues during the next few months the market might be so far drained of money that those who were obliged to pay the calls would have difficulty in arranging to get the necessary fund. The whole thing has been an interesting experience, although an extremely painful one and I shall be greatly relieved when matters finally drift—as they seem to be doing—into a state of dullness and cheaper money… . From all this long screed you may see that I am tired but hopeful, hopeful because of the simple fact that there is a tremendous productive capacity in this country, and that this productive capacity has not been one whit reduced by the colic we have all been having.24

Almost as suddenly as it had begun, there was a sense that the mounting crisis had been stopped. The source of optimism was likely twofold: the swift and bold actions of the Treasury, thus giving much‐needed liquidity to the capital markets, and the prospect of Americans buying £4 million in gold in London for shipment to New York. The Commercial and Financial Chronicle concluded that this “made a material change on Tuesday in the financial sentiment, the panicky tendency being arrested and a general advance in stock values taking place.”25 Within a few weeks, the disturbance in the markets seemed to have subsided.

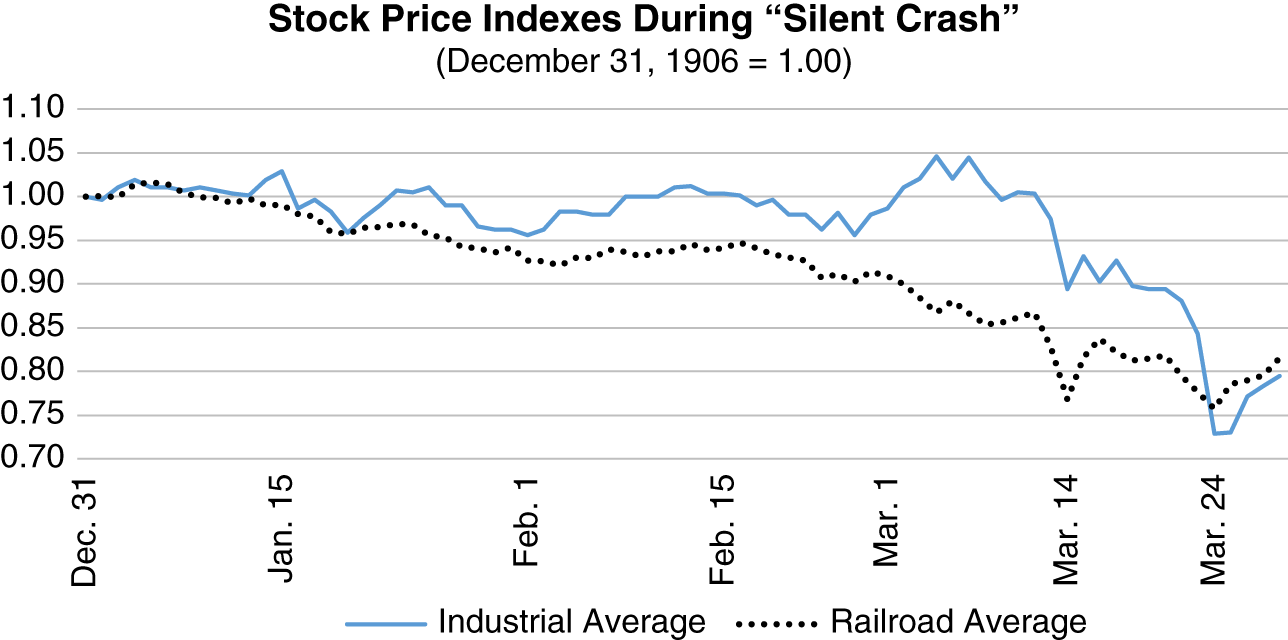

Figure 3.1 shows that a steady decline in railroad equities from early January presaged the sharp decline in the industrial average. Railroads, the glamour stocks of the day, were off almost 15 percent before the sharp decline of the industrials began in early March.

Figure 3.1 Stock Price Indexes January–March 1907

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on hand‐collected data from the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and the Commercial and Financial Chronicle.

Reflecting the financial anxieties caused by the March crash in equity prices, call money interest rates had spiked upward during this period, but they subsided when the surge of cash and gold into the New York money markets produced lower interest rates and a modest recovery in equity prices.b On April 13, the Commercial and Financial Chronicle observed, “The monetary situation has reversed its character for call money, from abnormally high to abnormally low rates—the relief in New York communicating a like tendency elsewhere. This change has opened the stock market here to more venturesome buying, and consequently speculative operators have again been in evidence.”26

While an optimistic mood may have returned, robust buying behavior had not. The Chronicle noted an eerie slackening of trading and persistently low stock prices, which suggested an absence of investors from the exchange. During April and May, the index of all stocks fell 3 percent, with large declines in shipping (down 12 percent), household goods (off 12 percent), machinery (off 10 percent), and copper (down 10 percent). On April 20, the Chronicle remained gloomy, saying, “no refuge from the old instability has been found. … A harsher and deeper economic irregularity is what the doctors have to deal with before real recovery will be under way.”27

Business fundamentals also looked bleak. For the month of April, the value of claims in bankruptcy had grown 38 percent over the same month a year earlier, with the sharpest growth in the manufacturing sector.28 On May 2, Teddy Grenfell in London queried Jack Morgan in a telegram about the stock market and when the banks in San Francisco might reopen.c Morgan replied, “Think further demand for gold is probable but impossible estimate amount. Stock market—believe decline largely speculative. Do not hear of any serious trouble any where though market vaguely apprehensive of difficulty arising largely from varied activities President USA.”29 For financiers and investors in 1907, the “varied activities President USA” were an overriding concern.

Roosevelt’s Progressivism

Despite his patrician mien and pedigree, President Theodore Roosevelt was masterful at giving voice to the nation’s popular will. By 1907, Americans had become increasingly disturbed by the tumultuous changes that had accompanied the country’s impressive industrial growth. They were worried about the number and type of immigrants entering the country; the size, noise, and frenzy of the nation’s large cities; the (in)effectiveness of their elected representatives; the consequences of old age, illness, and injury on the job; the day‐to‐day hazards of urban life; and even the quality of their food and water. Yet most of all they reacted with alarm to the rise of big business and the corporate merger movement. Some Americans, calling themselves “progressives,” argued vociferously for the right of a community to protect itself against those who pursued their economic self‐interest without concern for the common good.30 President Theodore Roosevelt became their most prominent advocate.

Progressives especially looked at J. P. Morgan and Wall Street with fear, some of it well founded. Since the Civil War, the history of corporate finance had been punctuated by instances of looting and self‐dealing by financial promoters. It seemed that the very intimate engagement of financiers as both insiders and outside investors opened conflicts of interest against which the public could not guard. Moreover, many of the combinations these investors organized resulted in oligopolies and monopolies that sacrificed the welfare of consumers for the benefit of investors.

The sheer scale of the new corporate trusts also raised concerns about the possible abuse of economic power to achieve political ends. Standard Oil, for instance, had the market strength to extract rebates from railroads for shipping their products that were not given to its competitors, documented by Ida Tarbell in a series of magazine articles in 1902 and then a best‐selling book in 1904. Other writers such as Upton Sinclair famously focused attention on unsanitary conditions in meatpacking in 1906. Ray Stannard Baker described perilous working conditions of coal miners in 1903, which was followed in 1907 by an investigation of Jim Crow living conditions for African Americans. In this context, the powerful and rather closed world of high corporation finance seemed very suspicious.

President Theodore Roosevelt personified this movement. He applied his executive power to challenge the influence of large corporations and to mediate between labor and capital. He was a pragmatist in a time of great political ferment, and he carefully navigated between opposing attitudes.

Most relevant for the events of 1907 were Roosevelt’s attitudes and policies toward large corporations. On the one hand, he accepted industrialization and the large scale of firms that it brought.31 He believed that large corporations were here to stay, and that the stance of government should not be to eradicate the large firms, but rather to identify and eliminate the types of combinations that were dangerous.d “I believe in corporations,” Roosevelt said early in his presidency. “They are indispensable instruments of our modern civilization; but I believe that they should be so supervised and so regulated that they shall act for the interest of the community as a whole.”32

To deal with the perceived ills of large corporations, Roosevelt also implemented a policy of regulation, mediation, and aggressive enforcement of the antitrust laws. In 1902, for example, Roosevelt initiated a series of important antitrust actions, beginning with a suit against the Northern Securities Company, a railroad trust organized by J. P. Morgan, James J. Hill, John D. Rockefeller, and E. H. Harriman in 1901 just five weeks after Roosevelt took office. Two years later, the Supreme Court ordered the company dissolved, yielding the first major enforcement action under the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. Roosevelt also filed suit against the unpopular “beef trust,” an action that the Court upheld in 1905. When states began filing state antitrust suits against Standard Oil between 1904 and 1907, Roosevelt directed the Justice Department to assume leadership of the campaign against the oil monopoly.33 By 1907, the Roosevelt administration had sued nearly 40 corporations under the Sherman Antitrust Act.

In that same spirit, Roosevelt revitalized the Interstate Commerce Commission, which had been created in 1887, by signing the Elkins Act of 1903 and the Hepburn Act of 1906, which gave the Commission the power to set maximum shipping rates for railroads. He also reenergized the presidency and asserted executive powers to protect particular social groups and supervise the economy in ways not seen since Reconstruction. In a Decoration Day speech (May 30, 1907) at Indianapolis, TR railed that the “predatory man of wealth” was the primary threat to private property in the United States:

One great problem that we have before us is to preserve the rights of property, and these can only be preserved if we remember that they are in less jeopardy from the Socialist and the Anarchist than from the predatory man of wealth. There can be no halt in the course we have deliberately elected to pursue, the policy of asserting the right of the nation, so far as it has the power, to supervise and control the business use of wealth, especially in the corporate form.34

Progressive activism was reflected at the state level as well; various states passed legislation sharply limiting the prices railroads could charge passengers. Business analysts believed these prices yielded revenues below the costs necessary to provide the services, thus inducing downward pressures on stock prices.35 The Chronicle opined, “What is ailing the railroads and the stock market? … The underlying cause is the same as it was at the time of the collapse in March, the same, indeed, as it has been for about a year and a half, during all of which period a shrinkage in values has been in progress. Owing to the assaults of those high in authority and adverse legislation both by Congress and the State legislatures, confidence is almost completely gone. No one is willing to buy at what appear like ridiculously low prices because no one can tell what the future may bring forth.”36

The judgment of some business leaders was that the break in stock prices in March 1907 had been sparked by investor fears arising from the Roosevelt administration’s aggressive attitude toward railroads and industrial corporations. “For a year we have been foretelling this catastrophe, an assured result of the trials railroad property, railroad men and other large capitalists have been forced to suffer,” the Commercial and Financial Chronicle said, commenting on a newly launched investigation of E. H. Harriman’s Union Pacific railroad. “What has just taken place is not the final scene. Hereafter, if the irritant is continued, as we presume it will be, it will not be so exclusively securities and security‐holders that will suffer; all sorts of industrial affairs are sure to get involved.”37 That irritant, of course, was the president of the United States.

President Roosevelt expressed surprise at the reaction of the financial community. In a letter to investment banker Jacob Schiff on March 25, Roosevelt wrote,

It is difficult for me to understand … why there should be this belief in Wall Street that I am a wild‐eyed revolutionist. I cannot condone wrong, but I certainly do not intend to do aught save what is beneficial to the man of means who acts squarely and fairly… . I do not think it advantageous from any standpoint for me to ask any railroad man to call upon me. I can only say to you, as I have said to Mr. Morgan when he suggested that he would like to have certain of them call upon me (a suggestion which they refused to adopt, by the way) that it would be a pleasure to me to see any of them at any time. Sooner or later, I think they will realize that in their opposition to me for the last few years they have been utterly mistaken, even from the standpoint of their own interests; and that nothing better for them could be devised than the laws I have striven and am striving to have enacted. I wish to do everything in my power to aid every honest businessman, and the dishonest businessman I wish to punish simply as I would punish the dishonest man of any type. Moreover, I am not desirous of avenging what has been done wrong in the past, especially when the punishment would be apt to fall upon innocent third parties; my prime object is to prevent injustice and work equity for the future.38

Whether Roosevelt’s complaints were mere posturing or accurate representations of the new industrial reality remained to be seen as the year 1907 unfolded.

Notes

- a. During this era, it was an open secret that investors—and even corporate executives—would manipulate the prices of corporate securities for profit (see, for instance, Edwin Lefèvre’s Reminiscences of a Stock Operator (1919)). To “boom” a stock was to bid up and maintain high stock prices, typically around the time of a new issue. Manipulation of stock prices in public markets was rendered illegal by U.S. securities laws beginning in 1933.

- b. Call money consisted of loans from banks to brokers that had to be repaid upon demand and were secured by bonds or shares of stock. The interest rates on call loans were a leading barometer of money market conditions. The variability of those rates in March and July 1907 reflected tightening credit conditions and anxieties of investors.

- c. The main reason San Francisco’s banks remained closed for several weeks after the earthquake and fire was to allow time for the vaults to cool. The fire was so hot in the financial district that if banks had reopened their vaults immediately after the fire had ended, the residual heat would have caused paper inside the vaults to burst into flame. This need to wait stilted economic recovery and made the city dependent on outside cash to pay for labor needed for the city’s intense rebuilding effort.

- d. Just weeks after the Panic, Roosevelt said, “It is unfortunate that our present laws should forbid all combinations instead of sharply discriminating between those combinations which do good and those combinations which do evil … The antitrust law should not prohibit combinations that do no injustice to the public, still less those the existence of which is on the whole of benefit to the public.” (Quoted from a public speech by Theodore Roosevelt, “Sherman Antitrust Law,” dated December 3, 1907. Used with permission of Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript library.)

- 1. Letter from J. P. Morgan Jr. to Edward Grenfell, March 14, 1907, Morgan Library and Museum, Box 5, letterpress book 3, January 24, 1907–January 15, 1908. Used with permission.

- 2. New York Times, March 15, 1907, quoted in Silber (2007), p. 11.

- 3. The decline of 10.9 percent was calculated as the sum of monthly returns over the period. Source of data: National Bureau of Economic Research, “Average Prices of 40 Common Stocks for United States” [M11006USM315NNBR], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M11006USM315NNBR, April 30, 2022. From February 1890 to August 1906, the mean monthly return on this index was 0.5 percent and the standard deviation was 0.052.

- 4. E. C. Grenfell to J. P. Morgan Jr., March 6, 1907. Used with permission of Deutsche Bank.

- 5. J. P. Morgan Jr. to E. C. Grenfell, March 6, 1907. Used with permission of Deutsche Bank.

- 6. Three telegrams between E. C. Grenfell and J. P. Morgan Jr., March 13, 1907. Used with permission of Deutsche Bank.

- 7. The loss of 8.29 percent was cited by Silber (2007), p. 33, second note and referring to an estimate by Jeremy Siegel, Stocks for the Long Run (New York: McGraw‐Hill, 1998), p. 183.

- 8. Commercial and Financial Chronicle, March 9, 1907, p. 534.

- 9. Noyes (1909b), p. 359.

- 10. Sprague (1910), p. 239.

- 11. Ibid., p. 241.

- 12. J. P. Morgan Jr., March 14, 1907. Used with permission of Morgan Library and Museum.

- 13. J. S. Morgan & Company to J. P. Morgan Jr., March 22, 1907. Used with permission of Deutsche Bank.

- 14. J. P. Morgan Jr. to J. S. Morgan & Company, March 23, 1907. Used with permission of Deutsche Bank.

- 15. “Roosevelt ‘Calls’ Wall St. Bluff. President Unmoved by Stock Flurry, Suspected of Being Engineered to Alarm Him,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 14, 1907, p. 1.

- 16. “Treasury Aid to Check Panic: Cortelyou, After Conferring with Roosevelt Announces Relief Measures,” New York Times, March 15, 1907, p. 3.

- 17. “Cortelyou Congratulated: Now the Administration Will Go to Killing Manipulative Panics,” New York Times, March 16, 1907, p. 3.

- 18. “Schiff Praises President: Banker Declares Roosevelt Has Rendered Good Service to Corporations,” The Washington Post, March 16, 1907, p.1.

- 19. Commercial and Financial Chronicle, March 23, 1907, p. 654.

- 20. “Cortelyou Calms Wall Street Anxiety: New York Financiers Ask Secretary’s Aid in Quenching Fire They Started Themselves,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 26, 1907, p. 1.

- 21. “Aids Money Market: Cortelyou Places $16,900,000 More in Circulation,” The Washington Post, March 27, 1907, p. 2.

- 22. “Bulls Force Rally: Active Stocks Move Upward and Bears Seek Cover,” The Washington Post, March 27, 1907, p. 1.

- 23. “Power of the Treasury,” The Wall Street Journal, April 25, 1907, p. 1.

- 24. J. P. Morgan Jr. to J. S. Morgan & Company, March 29, 1907. Used with permission of Morgan Library and Museum.

- 25. Commercial and Financial Chronicle, March 30, 1907, p. 716.

- 26. Commercial and Financial Chronicle, April 13, 1907, p. 832.

- 27. Commercial and Financial Chronicle, April 20, 1907, p. 851.

- 28. Commercial and Financial Chronicle, May 4, 1907, p. 1020.

- 29. Private cables, Morgan Grenfell Archives, Guildhall Library, London. Used with permission of Deutsche Bank.

- 30. A few of the most important works on this period are: McGerr (2003); Diner (1998); Wiebe (1967); D. Rodgers (1982); McCormick (1986), particularly Chapter 7, “Progressivism: A Contemporary Reassessment,” and Chapter 8, “Prelude to Progressivism: The Transformation of New York State Politics, 1890–1910”; and Eisenach (1994).

- 31. Essay by E. E. Morison and J. M. Blum in Morison (1952), Vol. 5, p. xvi.

- 32. Cooper (1983), p. 83.

- 33. McGerr (2003), pp. 156–158.

- 34. Ibid., pp. 156–158.

- 35. Commercial and Financial Chronicle, June 1, 1907, p. 1270.

- 36. Ibid., p. 1276.

- 37. Commercial and Financial Chronicle, March 9, 1907, p. 534.

- 38. Morison, Blum, Chandler, and Rice (1952), Volume 5, p. 631.