Photography as a cultural critique

FROM ‘UNCONCERNED’ PHOTOGRAPHS TO CONCERNED PHOTOGRAPHERS

One of Man Ray’s experiments with photography involved taking what he termed ‘unconcerned’ photographs. He would use the camera to take pictures by chance, with little or no regard for subject or composition. By introducing this random element into his photography he allowed the camera to document whatever happened to be in front of the lens at the moment he happened to press the shutter. At another extreme of photographic practice, we can find photographers who have consciously used the camera not to reflect the world, but have made a conscious effort to produce images that will change it.

According to the British Journal of Photography (February 1992: 16), Tom Stoddard’s picture of an ‘emaciated, Belsen-like Romanian orphan’ led to £40,000 worth of donations to relief charities within 24 hours of publication. Later, this figure was to rise to £70,000. This ‘earning potential’ for overseas aid seems to be true of images in general, though whether they have the ability to change opinions is another matter. In her comparison of the Mozambique floods (of February 2000) and India’s Orissa cyclone (October 1999), Isabel Eaton, a former BBC Newsnight producer, notes that although Orissa suffered ten times the number of deaths of Mozambique, the disaster only raised £7 million in aid in comparison to Mozambique’s £31 million (Eaton 2001). The unequal coverage can be put down to the fact that it was relatively easy for journalists to get to Mozambique and news people experienced less of a time difference than they would in India. This widened the possibilities for live broadcasts to coincide with the prime-time news slots of the European media. Also, in the Mozambique region there are not only better facilities and access to media technology, but also the availability of more comfortable hotels as well as R&R pursuits for off-duty news crews. Despite these considerations, Eaton believes it was the power of the visual images that was the overriding factor. The dramatic pictures from Mozambique had made the major contribution in generating donations to the disaster fund (Figure 7.1). It was a photogenic disaster featuring helicopter rescues, dramatic aerial shots of floods and sensational stories such as a baby born in a tree. This is in accord with the view of Mark Austin, reporter for UK’s Independent Television News (ITN):

When our television footage was broadcast, it had an immediate impact. Finally, the world took notice of the scale of the disaster. Aid agencies issued appeals and western governments were forced to respond, albeit slowly. It is perhaps Mozambique’s good fortune that this is a telegenic catastrophe. With no dramatic rescues, no riveting footage, would the world have noticed?

(Austin 2000)

As for the Orissa cyclone, the population suffered because their tragedy was not particularly photogenic. According to another ITN reporter, Mike Nicholson: ‘Pictures are everything, and it’s well nigh impossible to convince the viewer of the scale of the disaster when the only pictures we can show are unsteady shots of people casually wading knee-deep through a flooded rice field’ (Nicholson 1999).

In Chapter 3 we considered Frith’s mid-nineteenth-century standpoint where he had proposed that the truth of photography would, through its own intrinsic properties, have the power to change or influence people’s moral standpoints and tastes. However, some photographers have made it their business to pursue the conscious use of photography with the aim of changing views and opinions – sometimes with the ultimate intention of changing the world in which we live. This is one step removed from Frith’s notion of the replication of perfection, in that we are not necessarily looking for inherent characteristics of the medium as such which operate as agents of change. For example, in 1924, Moholy-Nagy had pointed out how the general cultural climate, combined with photographic representation, offered new viewpoints and consequently new ways of visualising and documenting the world:1

In the age of balloons and airplanes, architecture can be viewed not only in front and from the sides, but also from above. So the bird’s-eye view, and its opposites, the worm’s- and the fish’s-eye views become a daily experience.

(Moholy-Nagy 1924)

Similar notions were expressed in the work of Alexander Rodchenko, who believed he could find a new aesthetic through his photography that was appropriate to the new social order of post-revolutionary Russia (see p. 66 of this volume). This formalist version of Frith’s approach relied on the photographer’s ability to use the medium to show people what they would not normally be able to see – bringing issues to their attention through challenging their conventional perspectives of life. But we can move to consideration of another strategy: where the photographer is able to place him or herself in a privileged position and/or location to bring social or political issues to the attention of the viewer. The work of photographers Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine are particularly good examples in this context. Riis and Hine are considered to be the pioneers of social documentary photography. More recently, with the greater proliferation of photography, this approach has been developed by marginalised cultural groups (the Australian Aboriginal After 200 Years project, discussed on pp. 159–61) or social groups (the disabled, David Hevey (1992), for example). They have used the medium either to promote their own causes, or to challenge existing concepts and stereotypes in visual imagery. This said, there was the more unusual case of Amerindian photographer Martín Chambi who, in the 1930s, used his camera to explore his Inca heritage, to re-establish the lost history of his race as part of the Peruvian Indigenista movement. Chambi’s photographs display a sympathy and understanding of those he has portrayed and do not objectify the subject.

Figure 7.1

Helicopter rescue, Mozambique, 2001.

Photograph by Pool – Sunday Times. Copyright Reuters. Courtesy of Reuters.

Looking further back in history, to 1868, we find the photographer Thomas Annan working in Glasgow compiling a documentary record of the slum districts. He published an album entitled Old Closes and Streets of Glasgow and, although such images were not necessarily operating in a self-conscious role of social criticism, the photographs did have the virtue of revealing the camera’s potential to bring to a wider public evidence of social conditions and injustices. Similarly, John Thomson’s series was published in monthly instalments in 1876–7: Street Life in London. He went to working-class areas with the writer Adolphe Smith, photographed the population and made a sympathetic record of the ‘dangerous classes’. It is interesting to note that the cultural theories of social evolution, that were in vogue at the time of the Thomson and Smith project, viewed ‘lower-class women’ and criminals as sharing similar characteristics to ‘savages’ or ‘primitive’ man. This is perhaps most evident in the writings of Herbert Spencer (1870: II, 537–8). However, in the tradition of social documentation, Thomson and Smith were following a procedure initiated by Mayhew who, in 1851, had investigated London Labour and the London Poor. Mayhew was accompanied by daguerreotypist Richard Beard; however, the then technical limitations on photographic reproduction meant that the daguerreotypes had to be transcribed as woodcuts, and the originals no longer survive. Otherwise Mayhew and Beard might well have attained greater significance in the history of photography. They could have been seen as establishing the traditional approach of social documentary from the nineteenth century, through Agee and Evans of the 1930s, to contemporary collaborations between writers and photographers, Weisman and Dusard (1986) for example. But in Mayhew and Beard’s case, which relates to our discussion of the digital image, an image manipulated by an artist, even though it may have been derived from a lens projection, does not seem to maintain the same degree of power of observation and authenticity as the unmediated photograph. We can summarise Thomson’s use of the camera as being ‘observational’. As far as the accompanying text reveals, he took a sympathetic standpoint.

However, there is a long tradition of photographer/writer partnerships. Classic examples of photographer and writer include (respectively) Thomson and Smith and Evans and Agee. In fact, the American photographer Walker Evans recognises the sharp distinction between the roles of the writer and the photographer, which has a bearing on our reference to those who take on the combined tasks of reporter and photographer (p. 146 of this volume): ‘I now perceive … that there are different methods and approaches in these two projects, the writing and the photographic project’ (quoted in Newhall 1981: 318).

In the 1930s, Walker Evans had been employed on the Farm Security Administration project and began to work with journalist James Agee on an assignment for Fortune magazine (see Fleischhauer and Brannan 1988). Although the magazine finally rejected the story resulting from the collaboration between photographer and writer, who had lived with the sharecropper families for two months during the summer of 1936, their work was later published in book form as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941). According to Evans, it was the cooperation of the two men, their ability to gain the confidence of their subjects and their recognition of their individual skills that enabled them to achieve the assignment:

It was largely due to Agee’s tact and psychological gift that he made them understand and feel all right about what we were doing.… They were made to feel by both of us, I think, that they were participating in an interesting operation.

(quoted in Newhall 1981: 318)

As mentioned in earlier chapters, it is important for the photographer to develop the ability to make the subject feel relaxed and to gain their cooperation as a joint participant in the picture-making process. In contrast, we can find the opposite extreme in the use of photography as propaganda. Dr Barnardo recruited the camera for his own social crusade. Barnardo photographed children in the 1870s to show their condition and appearance in order to aid his fund-raising enterprises for his children’s homes. He used the diachronic technique of before and after pictures for this cause. These are held in the Barnardo photographic archive established in 1874 at Ilford in Essex. Not only was Barnardo accused of falsifying the information by making the children look worse than in actuality, (which in itself opens up some moral and selection/editing issues), but he was taken to court and found guilty of ‘artistic fiction’. This brought an abrupt end to this particular method, although he continued to fill the archive with some 50,000 more straightforward photographic portraits.

In contrast, on the other side of the Atlantic, in the United States Jacob Riis was photographing urban poverty from his point of view as a newspaper reporter in 1889. He benefited from the new technologies of dry plates and employed the early developments in the use of magnesium flash to make hitherto unrecorded scenes of interiors for his book How the Other Half Lives (1890) and his Children of the Poor (1898). It was Riis’ central aim in his role as an investigative journalist to publicise the living conditions of his subjects. For the publication of How the Other Half Lives, Riis worked closely with (President-to-be) Theodore Roosevelt to implement some actual social change.

The photographs brought about the closure of the lodging rooms (for example, as featured in Riis’ photograph Five Cents a Spot) and later the slums of Mulberry Street which he had also documented. It is nonetheless rare for the camera to achieve this scale of social reform where the direct result of the camera’s role between cause and effect concerning a single issue can be demonstrated, although in the broader media context we might look to the TV production Cathy Come Home, with regard to the UK housing crisis, and to the role of photography in the overall media coverage’s contribution towards bringing about the cessation of the Vietnam War. However, Riis had established a style of photographic practice which set the scene for sociologist Lewis Hine to create his own brand of social documentation with his photographs of the arrival of the immigrants on Ellis Island, New York, in 1904.

Lewis Hine (1874–1940) chose to use his camera to promote the need for changes in society. He concentrated on child labour and his documentary photographs provided evidence for the Progressive and Reform movements in the United States.

They were able to generate public concern and consequently appropriate changes in legislation. Hine’s attitude to photography was not dissimilar to the didactic approach taken by Britain’s Benjamin Stone (of an earlier generation): taking photographs as a form of evidence-gathering was a relatively uncomplicated realist approach but had the overall aim of educating the public. In this regard, both photographers probably intended to gather evidence of current conditions that would accrue additional value in its contribution to history in the future. As Alan Trachtenberg (1980: 111) has put it: ‘to be “straight” for Hine meant more than purity of photographic means; it meant also a responsibility to the truth of his vision’. While Hine believed that realism was an inherent characteristic of the photograph ‘not found in other forms of illustration’, he also held the view that while the medium may be ‘truthful’, the hand releasing the shutter can often be deceitful: ‘While photographs may not lie, liars may photograph’ (Hine’s ‘Social Photography’, in Trachtenberg 1980: 111).

In 1926 Hine returned to Ellis Island to continue photographing the new US immigrants and, in 1931, worked for the American Red Cross to photograph rural communities in Arkansas and Kentucky who were suffering from the drought. This helped to establish what we might term the humanitarian approach to social documentary photography. Hine referred to his style as ‘social photography’, which should be subject to a social conscience. It was not intended to be overtly critical: ‘I wanted to show the things that had to be corrected. I wanted to show the things that had to be appreciated.’

In 1930, in Berlin, the Workers’ International Relief established ‘Workers’ Camera Leagues’ which spread through Europe and across to the United States. They aimed to supply photographs to the left-wing press.

THE REVOLUTIONARY APPROACH TO PHOTOGRAPHY

In 1930s Europe the revolutionary approach to photography was characterised by Max Dortu’s poem (1930) ‘Come Before the Camera’ (reproduced in Mellor 1978: 45), which extols the use of the camera for its ability not only to photograph all strata of society, but also to unite all people in service of revolutionary victory. From another perspective, Edwin Hoernle describes ‘the working man’s eye’: the idea that the workers’ world was invisible to the bourgeoisie. In his view, photographers must ‘tear down’ those representations that are set against the background of bourgeois culture:

We must take photographs wherever proletarian life is at its hardest and the bourgeoisie at its most corrupt; and we shall increase the fighting power of our class in so far as our pictures show class consciousness, mass consciousness, discipline, solidarity, a spirit of aggression and revenge. Photography is a weapon; so is technology; so is art!

(Hoernle 1930: 49)

It is clear here that Hoernle is not seeking a well-rounded, balanced approach to the subject through employing the impartial camera. Rather, he sees an existing imbalance arising from a dominant culture which traditionally has maintained its control over the representations supplied to the masses. And, in his regard, the photographer’s documentary role is one of confrontation: to show and actively to promote the alternative point of view, to the exclusion of all else. He goes on to propose that the ‘worker photographers’ are the ‘eye’ of the working class, but they also have the duty to teach the workers ‘how to see’: the role of photography in the service of revolutionary activity is both to promote a particular viewpoint and to educate. It was in the same era that Walter Benjamin in his Short History of Photography was discussing the work of Atget and the achievements of surrealist photography, which creates an estrangement between human perception and our surroundings: ‘It gives free play to the politically educated eye, under whose gaze all intimacies are sacrificed to the illumination of detail’ (Mellor 1978: 69). This too suggests that photography can provide a new way of seeing.

In the United States, the Workers’ Film and Photo League started to produce propaganda movies. Hine joined this group in 1940 and it was the League that looked after and protected the interests of Hine’s work after his death. This branch of documentary practice, the social documentary, is not content simply to provide objective documentation; it also aims to use photography to influence opinions so as to change social conditions. Although news photography offers a type of documentation, its overall role is more concerned with recording events rather than with ongoing states or conditions. The notion of the ‘concerned photographer’ continues the humanitarian tradition. Cornell Capa organised two exhibitions entitled ‘The Concerned Photographer’: the first opened in 1967. Capa had consciously returned to the work of Hine with the aim of setting up the International Fund for Concerned Photography. The idea of this was that photographers could express and put forward a strong point of view from a variety of international perspectives. ‘The Concerned Photographer 2’ was held in 1973 and it perpetuated the humanitarian perspective. So, humanistic photography adopts a socially different role from that of revolutionary photography by adopting different means in its powers of persuasion.

THE ADVENT OF COLOUR

One of the expected characteristics of documentary photography is the stark, grainy, black and white image. Some photographers have maintained that the monochromatic image enhances the viewer’s imagination. The colours that are not present in the photograph can be somehow mentally filled in through the process of perception. In the mid-1970s photographers began to explore the artistic possibilities of the medium of colour photography in the documentary context. Until this time, serious photography had been associated with black and white, Ernst Haas being a notable exception. Photographing for Life magazine, he was one of the first photographers to explore the medium of colour photography, often to dramatic effect.

Apart from Haas’ approach of formal experimentation, colour photography seemed to be regarded as being too real, leaving little room for artistic expression or imagination. Colour images were felt to be in a somewhat contradictory position – they did not embody the harsh actuality demanded by such documentary modes as the news photograph, established by photographers like Weegee (see p. 106). Moreover, the colour photograph seemed also to embody other contradictions in its usage. From the 1960s, colour photography had been associated with the amateur market and the snapshot was seen as either a brash and cheap photography for the masses or, on the serious side, was reserved for the glossy commercial image, offering glossy images for glossy subject matter (still lifes, portraits, advertisements and plush architectural interiors). In addition to this, until recently colour images have had a reputation for instability and impermanence – colour photographs had a reputation for fading. Today, the new advances in photo-printing have gone a long way towards remedying the situation (see Meecham, p. 206 of this volume).2

However, colour photography has been in existence for a much longer period than most people realise. Colour images by Ducos du Houron were produced in 1877 and the Lumière brothers had introduced the autochrome process in 1907. In the mid-twentieth century, one of the few vehicles for the colour photograph was the National Geographic Magazine. Following this, in the 1960s there was an increased demand for colour photographs for such magazines as Life, Paris-Match and Stern. In the United Kingdom, the Sunday papers’ colour supplements began to emerge, bringing about a new market for colour photography, closely followed by the use of colour in the mainstream tabloids and broadsheets. From today’s viewpoint it may seem surprising that, only some 40 years ago, photographer David Duncan considered that colour was completely unsuitable for documenting war:

In the photography of war I can in a way dominate you through control of black and white. I can take the mood down to something so terrible that you don’t realise the work isn’t in color. It is color in your heart, but not in your eye.

(Schuneman 1972: 88)

Oddly reminiscent of Roger Fenton’s approach to photographing the Crimean War in the 1850s, Duncan remarked ‘I’ve never made a combat picture in color – ever. And I never will. It violates too many of the human decencies and the great privacy of the battlefield.’ (Duncan also gained a certain notoriety for his claim that the Vietnam photographs of the My Lai massacre were a hoax – see Goldberg 1991: 230.)

The ‘new color’

In the United States of the 1970s some younger photographers began to take a fresh look at colour. Photographers like Stephen Shore (see Figure 7.2) started using colour as a mode of expression. He managed to escape the stigma of colour’s amateurish or lavish reputation and, by using large format cameras (5 × 4 or 10 × 8), he evaded the association of colour with the snapshot. Having chosen minimal, austere subject matter and diminished the significance of the subject to emphasise the quality of the photograph, the viewer’s interest is directed towards the colour of the image. In contrast, Joel Meyerowitz followed more in the tradition of Cartier-Bresson and in the style of Gary Winogrand, but using colour. Other US photographers began to use a fill-in flash in conjunction with larger format colour photography. This served the purpose of accentuating the colour present in the scene, sometimes enabling it to emerge from the dark or drab streets. In the United Kingdom photographers such as Paul Graham and Martin Parr began to use colour, influenced by the United States’ ‘new color’, as it came to be called. In his introduction to Graham’s A1: The Great North Road, Rupert Martin writes:

Figure 7.2

Broad Street, Regina, Saskatchewan, 1974.

Photograph by Stephen Shore. (© Stephen Shore/Art + Commerce).

The bright, artificial colour of signs and buildings contradict but do not usurp the natural colour of the flat landscape which borders onto the road. Telegraph poles traverse a poppy field, a car dump focuses the eye as the fields stretch away. The interiors of cafés and hotels along the road with their vivid colours and old-fashioned décor become an expression of personality, humanising the road and alleviating its monotony.

(Martin, in Graham 1983)

CASE STUDY: INDEPENDENT PHOTOGRAPHY

‘Outsiders Photography’

For those photographers whose lifestyle is more akin to that of the professional artist rather than that of the commercial photographer, there are particular difficulties in working with colour photography. Not the least of these is the expense. The photographer can use a professional laboratory that makes available the time, sympathy and the dialogue to ensure the appropriate quality of printing. While traditionally they would set up the darkroom equipment that affords them their own control of the colour developing and printing processes, nowadays a computer and digital printer is more likely. However, both arrangements involve expenditure on professional equipment as well as the acquisition of different (though not entirely unrelated) specialist skills.

Charlie Meecham and Kate Mellor are independent photographers based in West Yorkshire (see Figure 7.3). Their photographic practice involves pursuing their own photographic projects and interests, which in many respects evolved from their working practices established when they were students at Manchester Polytechnic (now Manchester Metropolitan University). They work in a similar framework to that of the painter or sculptor in that their work reaches its audience through exhibitions, publications, sales of prints to individuals (as well as commercial organisations) and commissioned projects. In addition they are studio based and, unlike most photographers working in the mainstream commercial sector, they have developed the craft skills to see the entire process through from the conception of an idea to the production of the final exhibition print. In recent years they have had to face a major change in their working practice to take into account the demand for and scope of digital imaging.

Kate Mellor’s work has the underlying theme of the relationship between our environment and the beliefs we have about it. Her work aims to contrast the idea of landscape with the economic and physical realities, such as boundaries and ownership. One of her early projects, Island: The Sea Front (1997), involved a discussion of a traditional concern of photography: objectivity and the gathering of evidence, and cartography’s mathematical structuring of the terrain. More recently she has combined her photographic practice with academic pursuit and has gained a PhD: combining the history of architecture with theories of visual representation. She has photographed a number of architectural sites throughout Europe. Mellor’s photograph reproduced here is taken from a series titled ‘Topographies of the Image’. This work explores the foregrounded image of architecture in post-industrial regeneration areas in Northern Europe and links it to the history of its photographic representation. The series is part of a critical response to questions that emerged through her doctoral research on the image of architecture in conventional and alternative paradigms of practice especially regarding configurations of, and ideas about, photographic temporality. She says ‘The pinhole photograph of Stadttor designed by Petzinka Pink and Partners and completed in 1998 was taken on Easter Sunday 2011. The pale dots on the lawn are smashed boiled egg, remains of a game’ (see Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.3

Charlie Meecham and Kate Mellor in Nanholm Studio, Yorkshire, 1997.

Photograph by Terence Wright.

Charlie Meecham’s work (see Figure 7.5) demonstrates a different engagement with the environment. His initial interest in producing romantic images has evolved into exploring the impact of social and technological change on the landscape. His current preoccupation is with the changing design of the landscape that results from the massive investment in road-building and redevelopment projects that have taken place in the late twentieth century (Meecham 1987). Throughout history, trade routes have shaped the landscape and acted as conduits for cultural influence and exchange, though now our perception of the environment is mediated by frames (such as the television screen and the car windscreen). Charlie uses the camera to document the proliferation of road signs and other street furniture, as well as to reveal the emergence of new environmental spaces (e.g. the undersides of flyovers). Some 35 years later he has returned to the sites of his earlier photographs to document how the environment has changed over the intervening period. This rephotogoraphy project not only records environmental change, but has been subject to changes in working practice brought about by the digital revolution. He considers this ‘puts photography to work’ enabling people to come to terms with environmental change.

Figure 7.4

Stadttor, Düsseldorf. 2011. Original in colour.

Photograph by Kate Mellor.

He is currently working on a photography project which investigates the taxidermied models of dodos on display in natural history museums. There are a number of exhibits in Britain and worldwide which he aims to visit in order to photograph the converging or differing contexts of dodo exhibits or collections. He is also interviewing curators, taxidermists, researchers who have been involved in the dodo story. He has found that many of the dodo models contain little original material but are covered in feathers from other existing birds. They vary as ideas advance regarding developing knowledge about the species and the personal taste of the model maker. Despite this subjectivity, the models remain as a representation of extinction in museums dedicated to scientific samples. They are very popular with children and parents who maintain the dodo as a part of popular cultural history through the generations with the story of its demise.

Figure 7.5

Kendal Museum, 2012. (Dodo model made by Carl Church.)

Photograph by Charlie Meecham. Original in colour.

An essential problem for the independent photographer is that of maintaining financial solvency. Traditionally, this sector was mostly supported by part-time lecturing (this type of employment is now becoming increasingly difficult to find), by spending some time taking on commercial photographic work (lab work, for instance), gaining support from grant-giving bodies (for instance Regional Arts Boards) or through non-photographic employment (examples include working in a bar or driving a van). When Charlie and Kate first left college in the 1970s, there was a growth of interest in promoting independent photography and public funds were widely available.3 Over the last 25 years or more there has been an increasing dependence on commercial sponsorship in the form of matched funding. While this can be relatively generous, covering most of the project costs and increasing the likelihood of the exhibition and publication of the work, it can mean that it is the funders who become the arbiters of photographic taste. These points aside, Meecham and Mellor have evolved a unique solution to this problem by establishing their own photographic printing business, ‘Outsiders Photography’. They specialise in exhibition-quality colour hand-printing, a service they provide for other independent photographers or for artists who find that photography forms an integral component in the production and exhibition of more ephemeral art activities (for example, Andy Goldsworthy’s sculptures made from natural materials such as ice).

On the one hand, the advantages for their own photographic practice are that working in this way has enabled them to develop their printing skills to an exceptionally high standard. They have had the opportunity to obtain a unique insight into the practices and requirements of the art photography market – additional perspectives to the same market in which their own photographs feature. On the other hand, they used to find that the specialised printing equipment for both colour negative and reversal processes required a high capital outlay, which has not at all diminished in the digital era. And the setting up of a small business requires a considerable amount of time and energy that can detract from the pursuit of one’s personal photographic ambitions. There is also the risk of gaining a higher reputation, in the art photography world, as a competent practitioner of a technical and craft skill rather than as a creative artist in one’s own right.

They have also found that their modus operandi demands the additional skill of achieving the correct balance between one’s own work and that of others – in terms of time, income and commitment. At the same time, they are continuing to develop their practical and conceptual skills in the new technologies. For example, Kate has used the internet as an additional exhibition site. While they find that the new technologies are redefining practice, they have found it necessary to change and involve themselves in major reinvestment in technology and reskilling. As Charlie put it ‘I never thought I’d live through an industrial revolution!’ Fortunately the advent of digital imagery has been a gradual process and has not forced them to make a sudden switch. Indeed they continue to work with film and chemicals alongside the digital. However, the demand for photographic exhibition prints has reduced as the large commercial labs can undercut their prices. In contrast they are printing more for artists who work across processes – scanning and making digital prints on specialist papers, for example. Over the past 20 years digital imaging has become quicker, faster and much more sophisticated in offering a greater range of artistic and representational possibilities.

The life of an independent photographer can be financially precarious and potentially isolated, and many practitioners find it beneficial to belong to general independent photography groups. For example, in the Manchester area independent photographers set up www.redeye.org.uk the Redyeye photography network as a web-based special-interest group to facilitate social interaction and exchange of ideas to arrange lectures, seminars, portfolio discussions, exhibitions and cultural exchanges to serve the locality.

The documentation of other cultures is a particularly important and sensitive aspect of documentary photography. In the practice of ethnographic photography all the ordinary issues of photographic documentation become exaggerated: for example, whether the subjects are being taken advantage of, whether the reason for photographing is understood, whether the subject is treated as an object, etc. It also provides a valuable example of the ways that photographs can betray the standpoint of the photographer. In short, ethnographic images say as much, if not more, about the culture of the photographer than about the subject.

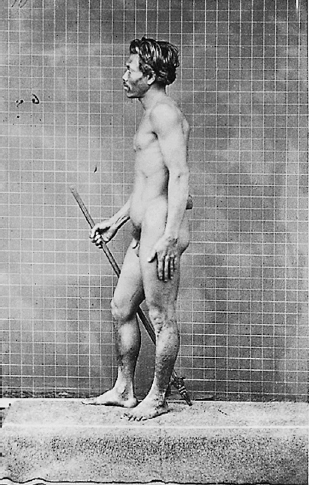

In the nineteenth century the anthropometric approach attempted to use the camera as a scientific instrument, in a similar manner to today’s use of it in forensic photography. Under the assumption that a camera could ‘transparently’ supply information, the image would yield exact mathematical data suitable for scientific investigation. Whether the subject was a human being or an object of material culture, in general they could be made quantifiable by the agency of the camera.

The evidence could be laid out on the table for comparison and classification. For the positivist approach, the realist view of photography seemed to provide an ideal medium for scientific documentation. It would provide an objective vision and collect facts which then could be organised and analysed in a systematic fashion. The photograph was viewed as a sort of container that could bring the subjects of anthropology directly into the academic’s study (see Figure 7.6).

Photography itself could constitute a means of imposition on another culture. It can be regarded as a significant Western phenomenon. An area of controversy arises as to whether photographs are naturally perceived. This has involved experiments where psychologists have shown photographs to various tribespeople to see if they perceive them as representations or as physical objects. Photography in the cultural encounter has given rise to a number of myths regarding stolen spirits and images or, according to Carpenter (1972: 130), the ‘terror of self-awareness’. Beloff (1985: 180) describes the use of photographs as ‘ritual relics’ throughout all cultures and quotes photographer Elliott Erwitt who suggests that in some cases it is photography that brings the event into existence. Whether this is true or not, the photograph is used to authenticate the event (such as a wedding for example), or it is a confirmation, saying ‘I was here’.

Often an individual becomes representative of an entire race or culture, is considered to be a typical Australian Aborigine or a Trobriand youth, and thus must conform to certain racial stereotypes or preconceptions. Similarly, the chosen moments for photography can become representative of that culture’s activities – ‘These are the people who …’. Or should they be named as individuals? Historically, the approach was rigid, strictly determined and was spelled out to the colonial layman travelling abroad with a camera: ‘to enable those who are not anthropologists themselves to supply the information which is wanted for the scientific study of anthropology at home’ (BAAS 1874: iv).

Figure 7.6

Anthropometric image of Malayan male, c.1868–9.

Photograph by J. Lamprey. Courtesy of the Royal Anthropological Institute.

Other issues of concern were the extent to which the subjects are objectified and the terms under which they can be said to be collaborating with the photographer. Do they understand the final outcome of the photograph? Or is it the situation of colonialism/tourism that may have forced them into collaboration? As Pinney (1992: 76) has pointed out, the colonial situation itself has exercised control over the subject: ‘Photography fitted perfectly into such a framework and can be substituted for the idea of discipline/surveillance in almost all of Foucault’s writing’ (see also Green 1984). According to Foucault, as with the issue of voyeurism, observation is to be considered a one-way process. Disciplinary power is exercised ‘invisibly’:

In discipline, it is the subjects who have to be seen. Their visibility assumes the hold of the power that is experienced over them. It is the fact of being constantly seen, of being able always to be seen, that maintains the disciplined individual in his subjection.

(Foucault 1979: 87)

Figure 7.7

Kultured kameraden: a study of Hun physiognomy, War Illustrated, 27 February 1917, p. 33.

Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum.

It should be added that photography was used not only to aid the pursuits of scientific rationalism in the context of nineteenth-century anthropology, but it also came to be employed for the pseudo-scientific pursuits of propaganda. ‘The Study of Hun Physiognomy’ (Figure 7.7) has taken on the trappings of the prevailing comparative method of the study of ‘physical specimens’, maintaining that the camera’s objectivity can, in itself, provide incontestable proof of racial development (Cowling 1989).

There are no set rules as to what makes a good documentary photograph. Whichever approach one takes there is the likelihood of infringing the rights of those photo graphed and the compromising of the accuracy of the representation. The very fact of being from another race, culture, nationality or class automatically poses a host of issues and problems. The best that the photographer can do is to tread carefully with an awareness of the broader issues arising from his or her undertaking:

In societies which are not over familiar with the camera as a technical means … the ability to take photographs is often taken to be a special, occult faculty of the photographer, which extends to having power over the souls of the photographed, via the resulting pictures.

(Gell 1992: 51)

Gell goes on to say that this so-called naive attitude to photography persists in Western culture and is evident, for example, when an artist is commissioned to produce a portrait of an absent leader as an icon bestowed with occult power ‘to exercise a benign influence over the collectivity which wishes to eternalise him’ (ibid.).

THE FUTURE OF PHOTOJOURNALISM?

Some photographers hold the view that the golden age of photojournalism has passed. Magazines such as Picture Post or Life have either ceased to exist or no longer carry the extensive photostory. In many respects, the function of the highly visual, or spectacular, story has been taken over by television. The photojournalist working for today’s newspaper colour supplements would be fortunate if three or four pictures were printed as a piece of photojournalism. Often the picture story consists of just one photograph, placing a greater requirement on the photographer to arrive at one striking image and using the single decisive moment to tell the story, rather than having the photographic narrative consisting of a number of possibly more sympathetic images to convey a more subtle idea or interpretation of events. This is in contrast to the pre-war peak of Picture Post in the day-in-the-life feature ‘Unemployed’ (vol. 2. no. 3, 21 January 1939) whereby (adopting a Mass Observation style of ‘random’ selection) ‘from a group outside Peckham Labour Exchange we picked out one, Alfred Smith, and followed him with the camera. On the following pages is the story of his daily routine.’ This picture story in total ran to 19 photographs.

It was not only changes in house style or editorial approach that led to the demise of traditional photojournalism and the rise of the new documentary era. In the new documentary, rather than focusing on the world out there and making use of the photographer’s privileged position that enabled him or her to secure images which would not be normally available to the general public, photographers came to make use of their immediate environment – the family or their domestic sphere – to show aspects of their own everyday life. The other impetus for this change was part of a more general social move instigated by the 1970s and 1980s rise of the feminist movement. Here one does not need to focus only on issues concerning equal rights, and equality of opportunity and access to education, etc., but also on those of sexuality. Issues of, say, birth control had been associated with feminism from the early days. But the broader contemporary concerns of the woman’s right to have control over her body, the questioning of the traditional institutions of marriage and the family, the patterns of heterosexual behaviour, and the roles and attitudes that have been imposed by the dominant society have all influenced photographers, who have used the camera to explore such themes and provide the means to question and to redefine roles and values.

So one influence from the changes in the outlet of photography has arisen from the photographic institutions themselves, and another from the social and political concerns of contemporary society. A central topic has been how people’s lives, as they are actually lived, conform or deviate from popular or dominant stereotypes of the nuclear family. These questions re-emerge in the case of the family snapshot. For example, Sally Mann’s book Immediate Family (1992) provides a good example of this genre of photography. The images resulting from her work are very different from the Picture Post example of the outsider looking at a member of another community (exemplifying the power relations between photographer and subject discussed earlier, which were also characteristic of the Mass Observation projects of the 1930s). So in this kind of documentary we are moving away from a colonial style of photography to that of participant observer.4 According to The New York Times Magazine (27 September 1992: 36) it was debated whether Mann had exploited her own children in making the book: ‘The photographs seem to accelerate the children’s maturity, rather than to preserve their innocence.’

Further questions can arise with this style of work in the light of current concerns about child abuse, the invasion of privacy or the betrayal of trust. There is the problem of the insider making public the members and activities of their own social group, perhaps abusing or exploiting the intimacy of the subject. Naturally, the issue of the public and private domains is also encountered in mainstream journalism. In the media in general, on the one hand, we have the soap opera where fictional entertainment is made of the mundane aspects of everyday life; on the other, the amusing aspects of amateur family videos find their way onto prime-time television.

Most of the issues dealt with in this chapter have arisen from the so-called postmodern crisis, which consists of a blurring of traditional boundaries – arguably, the old polarisations and dualisms of the Cartesian influence on traditional Western culture. There is no longer any safe territory or a secure strategy that can be adopted in making a photographic documentation, and this uncertain state has been exacerbated by the advent of digital imaging, where we can no longer be sure that the image we see documents anything at all. At best, photographers need to be aware of the issues determining their approach to the subject as well as the ethical implications and the representational considerations. They can then at least make an informed choice with regard to their documentary strategy.

• The aim of this chapter has been to show how attitudes have changed regarding photography’s ability to document. The central issue of the documentary photograph hinges upon the relationship between the camera’s ability to record and the selection of appropriate information by the photographer and it considered the power of the photograph to instigate social and cultural change.

• We began by looking at a brief history of social documentation and how photography in this context could bring aspects of poverty, which would have normally gone unseen, to the general public. The wider population may have known of the existence of those living in destitution, but photography (by making the subject a public issue) made it more difficult to ignore.

• We considered the new documentary approach to colour that took place in the 1970s and looked at the case study of ‘Outsiders Photography’ and their attempts to work as ‘independent’ photographic artists and how, in more recent years, they have struggled to come to terms with the encroachments of digital photography.

• The chapter concluded with a brief review of ethnographic photography and a consideration of the future role for photojournalism, which finds itself in a situation of realignment and reappraisal with the advent of digital imagining and the changing demands and roles in the magazine industry.

NOTES

1 See also the effect of aerial photography on painting in Scharf (1968: 176).

2 See Wilhelm (1993) The Permanence and Care of Color Photographs for the most comprehensive discussion and details of this issue.

3 One such example resulted in the publication of Homer Sykes’ (1977) Once a Year: Some Traditional British Customs, London: Gordon Fraser.

4 This is different from Malinowski’s notion of the ‘participant observer’ who, although living with and joining in the activities of the subject, remains an outsider. Malinowski’s methods had a profound influence over the MO project.